Matthew Dicks's Blog, page 40

October 19, 2024

Jeni’s great night!

You rarely get to witness someone’s journey from humble beginnings to their crowning achievement.

I had the honor and privilege of witnessing it last night.

I met Jeni Bonaldo in the spring of 2014 when I visited the high school where she teaches in Bethany, Connecticut, to discuss my latest book and share stories.

Actually, Jeni and I unofficially met back in 1998 when she attended her cousin’s wedding, and I worked as a DJ. She was 19 years old that day, so we didn’t know each other or even speak, but we shared a space for about six hours, never realizing that someday we would become great friends and storytelling partners.

Jeni did not know that storytelling was something people did, but when she watched me perform for her students, she thought she wanted to tell stories.

Soon, she was performing for Speak Up — Elysha and my storytelling organization — and quickly became a fan favorite.

Then, I took Jeni to her first Moth StorySLAM in New York City. Since then, Jeni has been competing in Moth StorySLAMs in NYC and Boston — often alongside me and occasionally with friends — so much so that last night, in New Rochelle, NY, as Jeni and I were getting drinks during intermission, someone referred to us as a “storytelling power couple.”

Despite many attempts, Jeni had yet to win a Moth StorySLAM. Part of this was bad luck—being chosen early in the evening (when it’s much harder to win), competing against annoying me, and coming exceptionally close to victory on a handful of occasions.

On the way to New Rochelle, Jeni told me, “I’d like to win just once.”

She told me it was her dream.

Honestly, it was my dream, too. I’ve won 61 Moth StorySLAMs, but every victory still feels amazing. I’m also as competitive as anyone I’ve ever known. But in recent competitions, I’ve found myself rooting more for Jeni than myself. She’s an extraordinary storyteller. I trust her above all others to deliver an outstanding performance every time.

She and I perform “Matt and Jeni Are Unprepared — a storytelling improv show, and I wouldn’t perform it alongside any other storyteller in the world.

She’s that good.

She deserved to win.

I wanted to see her win.

I wanted her dream to come true.

Jeni’s name was called sixth last night. She took the stage and performed brilliantly. I was so impressed.

Overwhelmed, really. She was hilarious, poignant, vulnerable, and technically superior.

When her scores were announced, with four storytellers still to go, she was in first place, but not nearly by the total I thought she deserved.

She was head and shoulders above the competition, but her scores placed her within striking distance of another good story.

I worried for the rest of the night. I worried that some injustice might occur.

I worried that a storyteller might tell a gem and steal her victory.

I actually worried that my name would emerge from the bag and I would be forced to tell my story after her, giving me the unfair but always present advantage of recency bias.

When two people tell great stories, the person who performs second often wins. I wanted to remain firmly in my seat.

I wanted Jeni to win so badly.

Then she did.

When her name was announced as the winner, I may have been as excited as she was.

It’s been such a privilege to witness someone discover storytelling ten years earlier in a high school library, then learn, hone, and perfect her craft better than most storytellers I know, and finally be recognized for her skill, talent, and hard work onstage before an adoring audience.

Last night, tears were in Jeni’s eyes as she took the stage to be recognized for her victory, but there were tears in mine, too.

I was so happy for my friend.

I can’t wait to see what she does next.

October 18, 2024

Two math realities you may not know

Here are a couple of math facts that not everyone apparently understands.

If you do, forgive me. I’m not implying this is groundbreaking mathematics.

Percentages (and ratios) are reversible

This means that 24 percent of 50 is the same as 50 percent of 24.

I showed this to someone last week, and it blew their minds.

But it’s true, and in many cases, it makes percentages — like the one above — much easier to calculate.

50 percent of 24 (12) is much easier to calculate than 24 percent of 50 (also 12, but

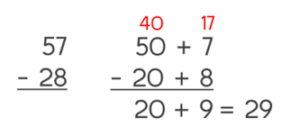

You can subtract without regrouping by simply using negative numbers.

So yes, a problem like 57 – 28 = x can be solved by regrouping (shown below).

But you can also subtract the digits in the ones column (7 – 8 = -1) and the tens column (50 – 20 = 30).

Then you’re left with 30 – 1 = 29.

I subtract using this method quite often.

I showed this to teachers at a training session years ago, and it blew their minds.

October 17, 2024

Weekend theory

A colleague asked me, “How was your long weekend?”

“I feel like I need another day to recover,” I said. Then, after a moment, I added, “Just how I like it.”

She looked at me like I had two heads.

So I explained my philosophy on weekends and vacations:

If you feel like you need another day to recover from the weekend or a vacation, you have succeeded.

While rest and relaxation are fine — no shade to those who want or need it — I want my weekends to be jam-packed. I want to look back on my weekend and know I sucked the marrow from those days. I want to know I took full advantage of every moment and lived those days to the fullest.

I explained to my colleague that his past weekend — a three-day weekend — featured:

An extra inning Little League playoff game

My Eagle Scout project

The Rocky Horror Picture Show at the Schubert Theater in New Haven

The Patriots game in Foxboro, MA

Two rounds of golf with friends

A golf lesson

Three bike rides — two outdoors

Family movie night

Meetings with six clients

I also finished reading a book and did a lot of writing — including a piece for a magazine.

It was not exactly the most restful or relaxing three days, but when I look back upon them, I feel like I lived them well and have a multitude of memories that will likely last a lifetime.

For me, this is supremely important. If I’m doing things I will likely remember long into the future, I’m making good choices about how I’m living my life.

Charlie said it best:

“You never really remember the time you spent on the couch.”

And he said it on Sunday afternoon, so yet another lasting memory from the weekend.

October 16, 2024

Americans might be rationale after all

Last month, I wrote about the importance of regulation and my fundamental distrust of businesses choosing to do the right thing because market forces demand it.

It turns out that despite Republican politicians fighting for less regulation, I am not alone.

A new YouGov survey asked respondents what industries should be more regulated and what industries should be less regulated.

Respondents, by a large majority, preferred more regulation over less.

The industries that the largest numbers of Americans said ought to be more regulated included:

Artificial intelligence (72 percent favor more regulation, 5 percent less)Pharmaceuticals (66 percent favor more, 10 percent less)Social media (60 percent favor more, 15 percent less)Firearms (57 percent favor more, 20 percent less)Health insurance (56 percent favor more, 16 percent less).Industries that Americans thought required less regulation include fashion, entertainment, and tourism.

When it comes to matters involving our health, safety, and security, a large majority of Americans support more regulation.

When it comes to businesses that have far less effect on our safety and well-being, Americans rightfully don’t care nearly as much.

This gives me hope.

Outside the vacuum of politics and tribalism, it seems that Americans are far more sensible and level-headed. When they aren’t trapped in their political bubble and simply asked to express their views, rationalism, it would seem, rules the day.

Huzzah?

October 15, 2024

Always do the thing

The plan was to attend the Patriots game on Sunday with Elysha, but when I awoke that morning, the forecast called for temperatures in the low 50s and a change of rain throughout the day.

Not exactly the kind of weather Elysha envisions when attending a Patriots game.

So, as the sun rose, I crept into the bedroom to tell her that if she wanted to bail, I would understand.

She did.

So I invited Charlie to join me, and surprisingly, he waffled. He attended his first regular-season game in September and loved it, but he complained last weekend when I attended the game with a friend instead of him.

I thought he’d be ready to go.

But the weather gave him pause, too, as did the prospect of four hours in the car and long walks across parking lots and up endless ramps when we could instead watch the game from the comfort of our home.

Eventually, he said, “I don’t know. What should we do?”

My answer was immediate:

“We go.”

Eight hours later, after watching our rookie quarterback show promise in an otherwise disappointing game, we climbed back into the car for the drive home. As I started the engine, Charlie said, “That was fun,” and he meant it.

Despite the loss and the less-than-ideal weather, we had a lot of fun together.

Even when your team loses badly, and the sun doesn’t shine, a day spent together is still fun.

I knew it would be.

I told Charlie:

This is why we went to the game today. Many people—maybe most people—choose the easier path. They choose comfort over challenge. They choose the couch over the plastic seats of section 333, row 15, seats 15 and 16 in Gillette Stadium. They choose the handful of steps required to walk into the living room instead of the 100-mile drive and three miles of walking required to see the game in person.

But who had more fun?

Who will remember this day a year from now?

Did anyone watching from home laugh as much as we did today?

Did anyone shout and cheer and jump up and down and high-five strangers and hug as much as we did today?

I told Charlie:

You rarely regret doing a thing, even when that thing requires effort and sacrifice.

You often — maybe always — regret not doing a thing.

I warned Charlie:

Never let effort, struggle, and sacrifice stand in the way of being out in the world, experiencing life, and doing things. When we do things, we make memories. When we do things, we allow the universe to open up and introduce us to new and wonderful things.

I think he understood, too. After a moment, he said, “I guess you never really remember the time you spent on the couch.”

“Exactly,” I said.

It was one of those rare moments as a father when I felt I had done my job perfectly.

And a hell of a lot better than the Patriots’ offensive line.

October 14, 2024

My Eagle Scout service project is complete. I can’t believe it.

After almost 36 years, I finally completed my Eagle Scout project on Saturday.

Almost certainly a world record in terms of how long it took someone to complete an Eagle service project, especially given you can’t become an Eagle Scout after the age of 18.

After a near-fatal car accident and my parents’ failure to request an extension to allow me to complete my project as a boy and earn my Eagle Scout badge — my literal boyhood dream — I decided to finally complete the service project that prevented me from becoming an Eagle Scout.

Happily, it was a glorious October day—perfect weather and the kind of foliage that attracts people from all over the world to New England.

My morning began with a lesson from a gravestone expert on properly cleaning a marker. She demonstrated the tricks of the trade and told me some great stories about the history of Center Cemetery, including recently finding lost markers inside overgrown bushes and hedges.

It breaks my heart how people die and are forgotten, which was the impetus behind this service project so many years ago.

After she left, I began working on a marker that needed a great deal of work—so covered in lichen that the name on the stone was barely legible—and quickly understood how physically taxing a job like this can be. I worked alone for about an hour before the first person arrived—a man named Eric — a Scout leader from Charlie and Clara’s troop.

A few minutes later, a second Eric arrived. I didn’t know this Eric, but he knew me. He had recently heard me interviewed on a podcast, began following me online, and learned of my project. Being an Eagle Scout himself, he decided to stop by and lend a hand.

I was thrilled. Overwhelmed, really.

Soon after the second Eric arrived, lots of other people followed:

Scouts from Clara and Charlie’s troop alongside their parents. More Scout leaders. A handful of my current students. Many friends. Neighbors. Strangers who wanted to help.

Also a boy who broke his collarbone riding his bike to the cemetery to volunteer. After having his arm set in a sling at an urgent care facility, he came to the cemetery to see if he could still help.

A total of 42 volunteers — plus Elysha, Clara, and Charlie — joined me on Saturday to clean markers.

So many volunteers that I was forced to run across the street to purchase additional supplies.

Clara served as our receptionist, welcoming volunteers, taking names and addresses for future thank you notes, and offering snacks and drinks. Charlie and Elysha worked hard cleaning markers, and an especially generous friend even dropped off a donation of donuts for the crew.

It was a great day of service, and I was overwhelmed by the kindness and generosity of so many people who joined me to make this small dream of mine come true. By the end of the day, we had cleaned more than 50 markers of lichen and debris.

At one point, I heard a boy say, “This is so satisfying. I started with a mess, and now it looks new again. I hope the dead people buried here are happy because I am.”

Many asked if completing the project might help me feel better about this lifelong, painful regret of mine.

My answer — less than satisfying — is “I don’t know.”

On Saturday, as the project was wrapping up, I was struck by how easy it would’ve been to complete this project when I was a boy had I not gone headfirst through a windshield or simply been gifted with a little more time.

It hurt a little, recognizing how close I had truly come to earning the rank of Eagle.

It still hurts today.

But I suspect that the passage of time might help me to feel better. Getting a little distance might help me put things into clearer focus.

I suspect that completing my service project will allow me to finally close the book on this part of my life, but I also suspect that the book will remain on my desk, staring back at me for the rest of my life.

My therapist has always admired the way I’m able to address the difficult moments of my life, then pack them away into boxes and place them on shelves, out of view, in what he describes as a very healthy means of moving forward.

I’d love to add this chapter of my life to the shelf, but I’m not sure if that will ever happen —at least for now.

Regardless, the kindness offered to me on Saturday will never be forgotten, and I couldn’t be happier to have completed something I’ve been thinking about for over three decades. Thanks to some good folks in the Newington Parks and Grounds Department, a lovely woman who knows a lot about cemeteries, and a remarkable crew of friends, family, students, Scouts, and even strangers, my little dream finally came true.

For that, I am still smiling today.

[image error]

[image error] [image error]

October 13, 2024

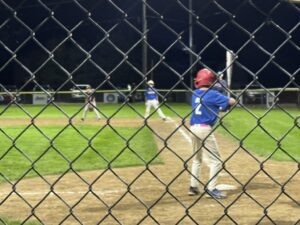

The end of another glorious baseball season

Charlie’s baseball team lost their playoff game on Friday night in an extra-inning nail-biter.

It’s the end of another baseball season, and an enormously successful one, too.

Charlie once played on a team that failed to win a single game all season. It was actually a tremendous learning experience for him.

He’s also played in (and lost) two championship games.

Last night, he lost in the first round of the playoffs, but his team went 8-1 in the regular season and performed brilliantly.

Charlie didn’t get to play catcher very much this season like he did in the spring, but his fielding improved, his hitting improved, and the team’s overall spirit was tremendous. It was the most efficiently coached, enthusiastic group of boys I have seen on a baseball diamond in my many years as the father of a ballplayer.

Thanks to incredible coaches, supportive parents, and clear expectations, it was a season I will remember for a long time.

I just wish we had more baseball to play.

But during the team’s final run around the field—a tradition after every game—Charlie and a teammate were bemoaning the opposing team’s enthusiastic celebration and the choice of music played after the winning run crossed the plate.

The opposing team was admittedly celebratory, but after an extra-inning game like this, it’s understandable. But in the minds of boys who just played their guts out and lost, it was tough to swallow.

Then, in the middle of this conversation, one of Charlie’s teammates ran past him and said something unkind. It was small, mean-spirited, and a little cruel, and given Charlie’s emotional state, it hit him hard.

It was a terrible thing to say to a teammate at any time, but at that moment, as the team was together for one last time after a heartbreaking loss, it was especially awful.

A terrible thing to do.

It would’ve upset most kids, I suspect.

It’s so hard to be a parent in these situations. So many things run through your mind.

First…

How dare you end my son’s baseball season on an act of unkindness and stupidity, you little monster. What the hell is wrong with you? Who stabs a teammate with a cowardly verbal knife at a moment like that?

Then…

Where is the boy? I’m going to give him a piece of my mind. I will make him feel just as terrible as he made my son feel. Or worse. I’m going to make him cry. And I’m incredibly good at doing so. It’s my superpower.

Then…

I always tell my students not to judge someone based upon their worst moment.

Then…

He’s only a boy, perfectly capable of acts of stupidity and cruelty because he still has a lot of growing up to do. I’m always telling people—including my kids—to afford others the opportunity to become better versions of themselves someday. This boy deserves this opportunity, too. He’s probably not a bad kid—just a kid who made a rotten decision at a terrible moment.

As a teacher, I see this from the best of kids every day.

Give the kid a break. He’s heartbroken, too.

Still, a small part of me wanted to hunt him down.

While driving home, I told Charlie that losing a baseball game is hard. Losing a playoff game is excruciating. Ending your baseball season on an extra-inning playoff loss is heartbreaking.

But I told him that in the grand scheme of things, the baseball game is small compared with the real test that night.

I told Charlie he had an opportunity to compete, support his teammates, try like hell, act with great sportsmanship, keep his head high, and be a good and decent person amid battle.

I told him:

You lost the baseball game but won the more important contest tonight, and sadly, your teammate did not.

That boy may play baseball better than you, but you’re a better baseball player than he will ever be because hitting and fielding aren’t nearly as important as those other things. Hitting and fielding will never be as important as being a good teammate.

“You won the bigger game tonight,” I told him. “Your teammate lost.”

I meant it, too.

I hope Charlie believed it because the end of the baseball season sucks— for both players and parents.

October 12, 2024

Pickpockets

At a dinner with his players, Arsenal manager Mikel Arteta secretly hired a team of professional pickpockets. The sleight-of-hand artists went around the tables, stealing phones and wallets from an unwitting first-team squad.

At the end of the meal, Arteta stood up and asked the team to empty their pockets.

Several players were missing valuable items.

The idea was to teach his squad the importance of being ready, alert, and prepared — at all times.

I was once the victim of a pickpocket. Many years ago, when Elysha and I were still just friends but on the verge of something more, she and I went to a bar with colleagues for dinner. As I exited the restroom, a man bumped into me. I thought nothing of it, but fifteen minutes later, I discovered that my wallet was missing.

Losing my driver’s license, credit cards, and cash was upsetting, but Elysha—whom I was almost certainly in love with already—offered to take me to the mall the next day to help me pick out a new wallet.

The loss of my valuable stung, but the opportunity to spend more time with Elysha more than made up for the theft. I remember being genuinely excited about shopping with Elysha the next day.

Less than two weeks later, we were together. So, who knows? Maybe that pickpocket did me a favor.

Today, I carry a wallet given to me by my mother-in-law, but that wallet I purchased at the mall with Elysha that next day sits in a drawer, waiting to be given to Charlie when the time is right.

The first thing his mother and father ever purchased together.

This Arsenal pickpocket idea is good on paper but not easily replicated in most circumstances. It’s a hell of a lot easier to do this kind of thing to a team of young athletes in a business with exceptionally limited employment opportunities and whose coach is the arbiter of their playing time and livelihood.

But in a more traditional professional setting?

“Pickpockets” is a tough expense to justify on any budget.

Human resources would also have a field day with this idea. People would likely be upset and offended upon discovering their phones and wallets had been stolen, even if it were done to make a point. Some would claim—perhaps rightfully so—that they were violated in some way during the course of the exercise.

I also suspect there are better ways to teach people to be ready, alert, and prepared at all times without having a stranger temporarily take possession of their valuables.

It’s a clever idea and makes for a great story, but would it be practical, economical, and realistic in almost any other context?

Probably not.

October 11, 2024

Eagle Scout service project ready to go

The weather Gods have cooperated and given me a sunny, 70-degree day tomorrow, which means I can complete my Eagle Scout project after waiting 36 years.

I’m very excited.

Town officials have been consulted.

Supplies are gathered.

Snacks and beverages will be offered to volunteers.

I’ve even arranged for an expert on gravestone cleaning to join me early in the morning to teach me the proper techniques for removing dirt, lichen, and other debris from headstones.

We want to do this job right.

It will be a great day — hopefully even better than the day I had planned when I was 17 years old.

If you’d like to join me, I’ll be at Center Cemetery in Newington, CT, at the corner of Main Street and Cedar Street, directly behind the Congregational Church, from 11:00 to 2:00 PM. Stop by for 15 minutes or three hours — to clean a headstone, clear debris, or simply say hello.

If you’re not familiar with the circumstances and reasons for this day:

Back in 1988, I was in the midst of completing my service project — the final step in becoming an Eagle Scout – when I went through a windshield during a head-on collision.

Datsun B-210 vs. Mercedes Benz.

While being transported to the hospital, my heart stopped beating, and I stopped breathing before two paramedics used CPR to restore my life.

It was no joke.

I was hospitalized for a week — including two surgeries on my legs (and a third years later) — and spent the next three months recovering from serious head, leg, and chest injuries. During that time, I turned 18 — the deadline for earning the rank of Eagle Scout.

I had aged out of the possibility of making my childhood dream come true during my recovery.

I was aware of this, of course, so I asked my parents to apply for a waiver, an exemption, or an extension that would allow me to recover and then complete my project.

They told me my request was denied.

For almost 25 years, I was angry with the Boy Scouts of America for denying me the opportunity to achieve my childhood dream. I still loved the organization that, in many ways, helped me become the man I am today and never waivered in my support for their good work. For a time, I served as an assistant Scoutmaster for a local Boy Scout troop, and today, Clara and Charlie are members of Scouting, but I could never understand why they would deny me the opportunity to earn the rank I had dreamed about for so long.

It really was my dream, too. Throughout my time in Scouting, I earned every merit badge I could find — well over the required number to earn the rank of Eagle. I quickly ascended the troop’s leadership ladder, moving from patrol leader to assistant senior patrol leader to senior patrol leader by the age of 14 — the highest level of leadership a boy could attain in a Scout troop. I could tie all the knots, swim all the strokes, pitch all the tents, and perform all the life-saving skills that my first aid merit badge demanded. I hiked for miles, built shelters using only twine and the natural elements, and spent hundreds of nights sleeping outdoors.

Scouting was my passion.

Then, a car accident derailed me from attaining my final goal.

For 25 years, I was angry about their decision, and then one day, just a couple of years ago, it hit me:

My parents never requested that waiver or extension.

Why would parents who had never spoken the word “college” to me, never attended a track meet to see me pole vault, never watched me compete in a marching band competition, and nearly missed my high school graduation make the effort required to ask the Boy Scouts of America for an extension.

Two years after this realization, while visiting my former Scoutmaster at a camp reunion, I asked him about it. He said he had no recollection of the request.

“That was a long time ago, so it’s possible, but I don’t remember one.”

Failing to earn the rank of Eagle Scout is one of the greatest disappointments of my life. I know it sounds silly, but when you dream of something for so long and work so hard to attain a goal, failing to make that dream a reality can be devastating.

Though it’s impossible to turn back the clock, and even though I suspect I will always feel disappointed for failing to achieve this goal, I decided to complete the service project I began as a boy to at least bring me some closure and perhaps help me feel a little better about my boyhood failure.

At last, I’m ready to go.

October 10, 2024

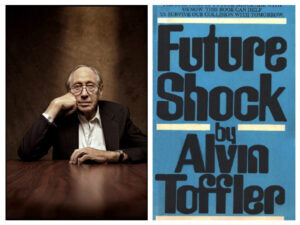

Learn, unlearn, and relearn

“The illiterate of the twenty-first century will not be those who cannot read and write, but those who cannot learn, unlearn, and relearn.”

This is a quote I like a lot.

It’s attributed to Alvin Toffler from his 1970 book “Future Shock.”

It strikes me that many people being left behind today are suffering from this very problem.

As an industry pivots, a sector of the economy transforms, and technology changes the nature of work, some people make great efforts to keep pace and evolve, while others watch their economic value atrophy and their ability to leverage skill and time diminish.

As a result, many become increasingly angry with a world they no longer recognize and cannot compete in.

Being a lifelong learner—something teachers have always hoped for their students—is essential to remaining viable and productive in a rapidly changing world.

Researchers at MIT, for example, found that 60% of the jobs existing in 1940 no longer exist today.

Similarly, Dell Technologies predicts that 85% of the jobs in 2030 haven’t been invented yet.

If you’re not constantly learning, evolving, and reinventing, your value in the job market diminishes almost by the minute. Whether you’re developing skills in a new sector or refining and expanding your skills in your current field, stagnation is economic death.

Thirty years before the dawn of the new millennium — decades before the age of the internet and the digitization of the world—Alvin Toffler said, “The illiterate of the twenty-first century will not be those who cannot read and write, but those who cannot learn, unlearn, and relearn.”

That was one prescient guy.