Thomas Wharton's Blog, page 9

November 5, 2012

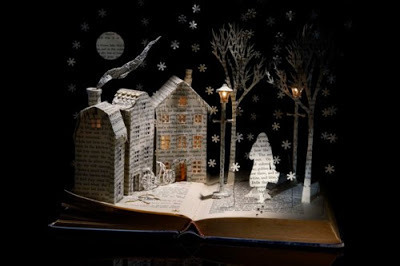

30 Novels, day 5: The Book of Wishes

30 Novels, day 5: The annual Christmas catalogue

When I was a kid a new edition of this eagerly-awaited novel came out every year, in the fall. I couldn’t wait to get my hands on it. I fought with my siblings over it. I poured over each marvelous page countless times as the snow fell and the holiday season approached. Well, to be accurate I only skimmed through most of the chapters because the ones I really wanted to read were the last few.

Okay, the Christmas catalogue wasn’t a novel. But then again, in a way it was. And still is. If one definition of the novel is a work of fiction about a society and its values, then the Christmas catalog was certainly a novel. As you turned its pages you saw good-looking, mostly pale-skinned people enjoying themselves in their new blouses and skirts and slacks and suit jackets. You saw them relaxing on their new sofas, admiring their new drapes, happily using their new cookware and vacuum cleaners. And in the last few chapters, you saw kids playing with their marvelous shiny new toys. Although oddly enough they usually weren’t playing with the toys, they were just posed beside them, smiling at them. There was something eerie about those kids. They were too well-behaved.

Each image in the book was carefully posed, perfectly lit. There was no conflict in this perfect world, which should have made it a very boring novel. But of course it wasn’t. It was pure wish fulfillment. Every page was a happy ending.

Except for those excluded from this ideal society. You didn’t see very many old people in the book’s pages. You didn’t see many people of different ethnicities, and no one with tattoos, or differently abled, or homeless, or sad. You didn’t even see just plain ordinary-looking people like the ones you knew. Everyone in the book was beautiful.

Maybe the Christmas Wish Book was really a utopian novel of the future. Surely the people in this book acted as if they lived in a society free of all of the hangs-ups of ours. The women seemed perfectly happy to stand around in their bras and girdles without a trace of shame or embarrassment, and the same for the men in their briefs and long underwear. How strange that it wasn’t okay to want to look at undressed people in real life, but okay to look at them in a book.

When I was a kid the novel took me to a kind of toyland heaven, where there were never any adults around. If only I could get all of the things I saw and desired in those pages. If only that’s the way life really was. If only, if only…

Published on November 05, 2012 07:10

November 4, 2012

30 Novels, # 4: "All the world will be your enemy"

Watership Down, by Richard Adams

I was eleven, I think, when I discovered this book about a heroic band of rabbits on a quest to find a new home.

Adams made their world so real. The rabbits had their own language, customs, stories, mythology, superstitions. An entire cosmos of imagination taking place in a few grassy acres, mostly unseen by the big blundering humans living nearby.

Each rabbit was a distinct character. Each had a personality, and valuable qualities and skills that the reluctant leader, Hazel, discovered he could put to use for the good of the group.

I became so utterly wrapped up in this book that I brought it to school to tell my friends about it. I suggested we form a club based on the novel, in which each of us would take the names of the rabbits in the story and … do what? I wasn’t sure. Have adventures, I supposed. The real fun was assigning a rabbit name to each of my friends, based on how their personalities matched those of the characters in the book. One of us would be Bigwig, another would be Dandelion, another Blackberry, and so on. I knew for sure I had to be the clever, self-effacing leader, Hazel.

My enthusiasm for the book was so great that I think I actually managed to convince this troop of rowdy boys to follow my lead and pretend they were rabbits. At least for one recess period. Until my band of rabbit brethren fell apart because the boys wanted to chase the girls, who were wondering why the boys weren't chasing them.

I was eleven, I think, when I discovered this book about a heroic band of rabbits on a quest to find a new home.

Adams made their world so real. The rabbits had their own language, customs, stories, mythology, superstitions. An entire cosmos of imagination taking place in a few grassy acres, mostly unseen by the big blundering humans living nearby.

Each rabbit was a distinct character. Each had a personality, and valuable qualities and skills that the reluctant leader, Hazel, discovered he could put to use for the good of the group.

I became so utterly wrapped up in this book that I brought it to school to tell my friends about it. I suggested we form a club based on the novel, in which each of us would take the names of the rabbits in the story and … do what? I wasn’t sure. Have adventures, I supposed. The real fun was assigning a rabbit name to each of my friends, based on how their personalities matched those of the characters in the book. One of us would be Bigwig, another would be Dandelion, another Blackberry, and so on. I knew for sure I had to be the clever, self-effacing leader, Hazel.

My enthusiasm for the book was so great that I think I actually managed to convince this troop of rowdy boys to follow my lead and pretend they were rabbits. At least for one recess period. Until my band of rabbit brethren fell apart because the boys wanted to chase the girls, who were wondering why the boys weren't chasing them.

Published on November 04, 2012 10:58

November 3, 2012

30 Novels, # 3: The Double Hook

The Double Hook, by Sheila Watson

"There's things to be done needs ordinary human hands."

I was trying to write a novel. I was in the MA program at the University of Alberta, and I’d decided that instead of writing my thesis on James Joyce’s Ulysses I would take the creative writing option and try to become a novelist myself.

The problem was, I couldn’t seem to write a novel. I kept starting them, and after a couple of chapters I’d lose momentum, or direction, or interest, and I’d abandon the thing. Then I’d start again. I knew I wanted to tell a story set in the Canadian Rockies, a place that I’d lived and that haunted my imagination, but I had no story. I had no plot. I was sure I had to have a plot all worked out first, but every plot I came up with seemed stale, familiar, clichéd. My plots bored me.

Two crucial encounters showed me the way. I went to see Kristjana Gunnars, who taught fiction-writing in the department at that time, to ask her if she'd be my thesis supervisor. I explained apologetically that I was trying to write a novel set in the mountains but all I’d come up with was this mess of fragments.

She said, “Fragments. That’s good. You can work with fragments.”

It was a bolt from the blue. So it was possible to write a novel without starting at chapter one and writing each chapter in sequence until you got to the end? Without having a plot all worked out? Yes, it was. I could take these unfinished fits and starts and treat them like jigsaw puzzle pieces, moving them around, finding links between them, shaping them to fit together. I could stitch a novel together out of fragments. I could find its shape, its plot, its story, as I went along.

The other crucial encounter was with a book. The book was Sheila Watson’s The Double Hook. First of all, this was a story set among mountains, about an unstoried part of the world. It was Canadian. It was western Canadian. It meant I wasn’t writing in a void, but in a tradition. And this was a novel unlike most I’d ever read. Its language was sparse, pared down, but poetic. It seemed to have been put together the way I was trying to put a novel together: out of brief flashes of lightning illuminating a moment, a person, a landscape. A book of fragments, tied together by mood, and by place.

And perhaps most important, the author had lived and taught and written here, in Edmonton, in the place where I was struggling to become a writer.

"There's things to be done needs ordinary human hands."

I was trying to write a novel. I was in the MA program at the University of Alberta, and I’d decided that instead of writing my thesis on James Joyce’s Ulysses I would take the creative writing option and try to become a novelist myself.

The problem was, I couldn’t seem to write a novel. I kept starting them, and after a couple of chapters I’d lose momentum, or direction, or interest, and I’d abandon the thing. Then I’d start again. I knew I wanted to tell a story set in the Canadian Rockies, a place that I’d lived and that haunted my imagination, but I had no story. I had no plot. I was sure I had to have a plot all worked out first, but every plot I came up with seemed stale, familiar, clichéd. My plots bored me.

Two crucial encounters showed me the way. I went to see Kristjana Gunnars, who taught fiction-writing in the department at that time, to ask her if she'd be my thesis supervisor. I explained apologetically that I was trying to write a novel set in the mountains but all I’d come up with was this mess of fragments.

She said, “Fragments. That’s good. You can work with fragments.”

It was a bolt from the blue. So it was possible to write a novel without starting at chapter one and writing each chapter in sequence until you got to the end? Without having a plot all worked out? Yes, it was. I could take these unfinished fits and starts and treat them like jigsaw puzzle pieces, moving them around, finding links between them, shaping them to fit together. I could stitch a novel together out of fragments. I could find its shape, its plot, its story, as I went along.

The other crucial encounter was with a book. The book was Sheila Watson’s The Double Hook. First of all, this was a story set among mountains, about an unstoried part of the world. It was Canadian. It was western Canadian. It meant I wasn’t writing in a void, but in a tradition. And this was a novel unlike most I’d ever read. Its language was sparse, pared down, but poetic. It seemed to have been put together the way I was trying to put a novel together: out of brief flashes of lightning illuminating a moment, a person, a landscape. A book of fragments, tied together by mood, and by place.

And perhaps most important, the author had lived and taught and written here, in Edmonton, in the place where I was struggling to become a writer.

Published on November 03, 2012 07:30

November 2, 2012

30 Novels, # 2: Signatures of all things I am here to read

James Joyce's Ulysses

It was the early 1980’s. I had just broken up messily with my girlfriend and I was working at a career that gave me no sense of accomplishment or satisfaction. I was angry, lonely, directionless.

Around that time I picked up Ulysses in a bookstore. I had tried to read this novel several times before but I’d never gotten beyond the first few pages. Stephen Dedalus struck me as a cold, unsympathetic character. This time, I kept going beyond those first few pages. Maybe I was more like Stephen than I’d been willing to admit. He seemed cast adrift and directionless, too.

I kept at the book. It was a challenge, and I needed a challenge. I needed something to take me out and above my troubles so I could see my life from a different, larger perspective.

I took Gifford’s Ulysses Annotated out of the library and read the novel in the evenings with the annotations at my side, penciling notes into the margins of my copy of the novel. Like a monk I kept at this for weeks, a few paragraphs at a time. Slowly learning to find my way in Joyce’s world.

The book became my Bible. I quoted from it to my friends (to their confusion and indifference). Joyce’s dazzling stylistics became a lens through which I read my own world.

I started writing my own sketches of the city and life around me, noticing details I would normally have ignored. Sights. Sounds. Smells. Voices. Mannerisms. Patterns. The wonder and the squalor and the radiant ordinariness of things. I saw more, and paid more attention, because of this book.

One day around this time someone asked me what I really wanted to do with my life. For the first time (out loud) I said, “I want to be a writer.”

Published on November 02, 2012 07:08

November 1, 2012

30 Novels: The Clocks Were Striking Thirteen

In celebration of National Novel Writing Month, as well as just for the heck of it, each day this month I’m going to talk about a novel that has shaped my life in some important way. Each day I’m going to tell a brief story about a timeless book.

Thirty days, thirty novels. Books that opened new worlds for me as a reader. Books that expanded my consciousness, sometimes in painful or scary ways. Books that turned me into a writer.

I’m not going to describe the plot of each book. Instead, I want to describe a moment of wonder, mystery, fear, or transformation. Thirty unforgettable moments in the life of a reader.

A couple of points to note at the outset: the books I talk about this month might not all be novels. And there will probably be one imaginary book among them (see if you can spot it).

I also hope to get at least one guest post, so if there’s a novel that matters deeply to you and you’d like to share your passion for it with others, drop me a line.

I’m going to start the month with George Orwell’s 1984.

A terrifying story, and yet there was something strangely appealing about Orwell’s dystopian vision of the ultimate police state, where one’s every action and thought is under scrutiny. It was a dramatic magnification of my own world. As a teenager I felt surrounded by watchful eyes and powerful voices, voices telling me who I was and who I was supposed to be. My secret inner life of dreams and fantasies often seemed completely at odds with this image of what society said I was, and what mattered.

Reading 1984, I could imagine pitting my own will and cunning against the watchful eye of Big Brother. I was sure that if it was me in the story instead of Winston Smith, I could fool the Party and survive.

And I loved the clunky, steam-driven novel-writing machines.

Thirty days, thirty novels. Books that opened new worlds for me as a reader. Books that expanded my consciousness, sometimes in painful or scary ways. Books that turned me into a writer.

I’m not going to describe the plot of each book. Instead, I want to describe a moment of wonder, mystery, fear, or transformation. Thirty unforgettable moments in the life of a reader.

A couple of points to note at the outset: the books I talk about this month might not all be novels. And there will probably be one imaginary book among them (see if you can spot it).

I also hope to get at least one guest post, so if there’s a novel that matters deeply to you and you’d like to share your passion for it with others, drop me a line.

I’m going to start the month with George Orwell’s 1984.

A terrifying story, and yet there was something strangely appealing about Orwell’s dystopian vision of the ultimate police state, where one’s every action and thought is under scrutiny. It was a dramatic magnification of my own world. As a teenager I felt surrounded by watchful eyes and powerful voices, voices telling me who I was and who I was supposed to be. My secret inner life of dreams and fantasies often seemed completely at odds with this image of what society said I was, and what mattered.

Reading 1984, I could imagine pitting my own will and cunning against the watchful eye of Big Brother. I was sure that if it was me in the story instead of Winston Smith, I could fool the Party and survive.

And I loved the clunky, steam-driven novel-writing machines.

Published on November 01, 2012 07:03

October 29, 2012

Kiss of Death: A Halloween Tale

Even the wrapper they came in was unappealing. Orange and yellow and black.

Candy kisses. Who made them? Where did they come from? No kid on the planet liked them.

When we hauled home our sacks of goodies at the end of Halloween night and dumped them out on the floor to see just what we’d gotten, we’d inevitably be saddened to find that a disappointingly large percentage of our take consisted of these hard, seemingly inedible, joyless “kisses.” But we didn’t throw them out. Our moms wouldn’t let us. That would be a waste. And technically they were candy, after all. We didn’t want to part with them, either, because of that fact. They had the virtue of at least making your mound of sugary loot look bigger. They bulked out the haul.

But inevitably, over the next few days, as we gobbled up all the other candy we’d collected, the dreaded Wrapper of Sadness began to predominate in the pile, and it got harder to avoid the realization that soon we would consume all the good stuff and then there would only be those things left, and then what? Like survivors in a lifeboat who’ve run out of food, we were now forced to contemplate the dreadful thought of eating what decency and rightness told us should never be eaten.

But we ate them. When we were younger and didn’t believe our older siblings who told us that they were gross and we’d be sorry, we ate them. First we had to get the wrapper off, and that was part of what made the candy kiss an instrument of deceit and misery, too, because half the time the wrapper was indelibly stuck in the candy and wouldn’t come off, or would only half come off. The rule was you didn’t have to eat those ones. You could throw the half-wrapped ones out because you’d given it your best shot, you’d tried to eat the thing and it had resisted.

But if you did manage to get the wrapper off in one piece, you felt like a kid who opens a present at Christmas to find socks and underwear inside. Because the candy kiss now had to be eaten, but it could not be eaten. It looked like candy but it was made of plastic cement.

We created our own urban legend around the candy kiss. It was said that if you actually ate one, it would remain in your stomach forever, and other bits of food would get stuck to it, until it made a huge ball that would block your intestines up and kill you. Truly the kiss of death.

Candy kisses. Who made them? Where did they come from? No kid on the planet liked them.

When we hauled home our sacks of goodies at the end of Halloween night and dumped them out on the floor to see just what we’d gotten, we’d inevitably be saddened to find that a disappointingly large percentage of our take consisted of these hard, seemingly inedible, joyless “kisses.” But we didn’t throw them out. Our moms wouldn’t let us. That would be a waste. And technically they were candy, after all. We didn’t want to part with them, either, because of that fact. They had the virtue of at least making your mound of sugary loot look bigger. They bulked out the haul.

But inevitably, over the next few days, as we gobbled up all the other candy we’d collected, the dreaded Wrapper of Sadness began to predominate in the pile, and it got harder to avoid the realization that soon we would consume all the good stuff and then there would only be those things left, and then what? Like survivors in a lifeboat who’ve run out of food, we were now forced to contemplate the dreadful thought of eating what decency and rightness told us should never be eaten.

But we ate them. When we were younger and didn’t believe our older siblings who told us that they were gross and we’d be sorry, we ate them. First we had to get the wrapper off, and that was part of what made the candy kiss an instrument of deceit and misery, too, because half the time the wrapper was indelibly stuck in the candy and wouldn’t come off, or would only half come off. The rule was you didn’t have to eat those ones. You could throw the half-wrapped ones out because you’d given it your best shot, you’d tried to eat the thing and it had resisted.

But if you did manage to get the wrapper off in one piece, you felt like a kid who opens a present at Christmas to find socks and underwear inside. Because the candy kiss now had to be eaten, but it could not be eaten. It looked like candy but it was made of plastic cement.

We created our own urban legend around the candy kiss. It was said that if you actually ate one, it would remain in your stomach forever, and other bits of food would get stuck to it, until it made a huge ball that would block your intestines up and kill you. Truly the kiss of death.

Published on October 29, 2012 06:49

October 25, 2012

The Knowmes

Quite possibly the most irritating beings in all the Perilous Realm are the Knowmes. This crabbed, humourless race dwells by the Sad Grey Lake in the Great Scarred Land, where they busy themselves every day at their many profitable industries, which make them rich but also make the lake more grey and the land more scarred.

They inform anyone who asks that they are unrelated in any way to the more familiar garden-variety gnomes of the ferny woods, with their jolly white beards and red caps. And that is why they insist on the unusual spelling of their name. For they will tell anyone who makes the mistake of calling them gnomes that they are not gnomes, they are Knowmes, the keepers of Knowledge (or as they call it, Knowmledge). They value facts only, hard data, the kind of information that they can make use of for their own profit.

If someone mentions one of their hated rivals, for example Gnome Chomsky, they roll their eyes and speak condescendingly of his discredited theories.

A conversation with one of these beings will consist mostly of the Knowme telling you “I already knowm that.” Indeed, they will inform anyone they meet that whatever they knowm about is what’s worth knowming, and whatever they don’t knowm about isn’t. Although they’re not often willing to admit there’s anything unknowmn to them. Their arrogance really knowms no bounds. When confronted by information that’s new and unfamiliar to him, a Knowme will put on a knowming expression and nod knowmingly, as if it’s already aware of these facts.

If you’re ever in the presence of a Knowme on those rare occasions when its forced to admit there’s something it doesn’t knowm, you had better turn and run, because Knowmes deal with these situations by turning purple and exploding. As a diversionary gambit this is of course quite drastic, but it does have the side benefit of keeping the Knowme population in check.

Of course there's probably much I don't know about these beings, so don't take my word for it. I'm not an expert in Knowmology.

Published on October 25, 2012 06:38

October 22, 2012

Box of Crayons

Box of Crayons: an artist’s story.

Box of Crayons: an artist’s story.When I was seven my mother bought me a great big box of crayons. She was an artist and she wanted me to be an artist too. The box held more crayons than I’d ever seen in my life. They were lined up in neat rows, like the soldiers of a rainbow army. “It’s every colour in the world,” I said to my mother. My older sister overheard this and scoffed. “There are way more colours,” she said. “There are infinity colours.” She always knew more than I did, but this time I wasn’t sure I believed her. How could there be so many colours that there was no end to them? My mother advised me to take the crayons out one at a time and put them back in their proper places in the box when I wasn’t using them. That way, she said, I could always easily find the colour I wanted. That seemed a sensible idea, and I was a cautious kid, so I did my best to keep the crayons in order. It was easy at first, mostly because I liked saying the colourful names of the colours as I put them back in their places. Desert Dune. Aquamarine. Lemon Dazzle. October Twilight. But eventually, after a few afternoons with my colouring books, the crayons were no longer lined up in their proper places. In fact most of them weren’t in the box anymore either but scattered over my bedroom floor with all my other stuff. Finally, when the mess reached the adult-annoying stage, my mother ordered me to clean up my room. She noticed the crayons lying around and asked me to put them back in their places. I did the best I could. I started with white in the upper left-hand corner and from there lined up the various hues, tints and shades so that they appeared to flow in the right order. When I got to black in the lower right hand corner I stepped back and decided that I’d done it. Everything looked to be in its proper place. And then I looked more closely. There was a gap. Like a smile missing a tooth. There was a space for one more crayon. I searched my room but I couldn’t find it. And even more perplexing, I had no idea what colour it could be. As far as I could tell, I had the entire rainbow. The greens, the reds, the blues, and all of their neighbours. I looked through the already-coloured pages in my colouring books for the trace of a crayon I might have used that didn’t match any of those in the box. I couldn’t find it there either. I never found that crayon. And I never discovered what colour it was. Sometimes I imagine it must have been infrared or ultraviolet, so that the crayon was actually there but I couldn’t see it. Sometimes, when I’m blending pigments with a brush on my paint palette, or pixels with a mouse on my computer, I close my eyes for a moment and I see that lost crayon. For an instant its unrecoverable colour shimmers before my sight. I have a name for it: infinite everyhue.

Published on October 22, 2012 06:58

October 19, 2012

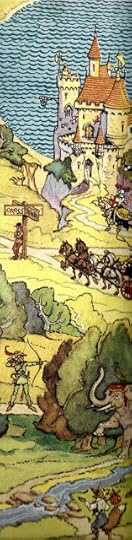

The Little Kingdoms

A traveler riding north from the Bourne will see a range of widely-scattered hills, with a castle on top of each hill. These are the Little Kingdoms. Each is a small country, tiny by the standards of most kingdoms, generally consisting of only one or two villages and surrounding farmland clustered around the castle on the hill. The kingdoms are generally peaceful places where very little changes over the years, but they all have one curious feature: if you are a plucky, good-hearted young man or woman setting out to make your way in the world, you’re very likely to have a great life-changing adventure in the Little Kingdoms.

These are lands of strange fortune where a woodcutter’s son can end up marrying a princess and becoming king, or where a miller’s daughter may persevere through great hardship to marry a prince and become queen. And if there is no adventure to be hand within the kingdoms themselves at a particular time, the Deep Dark Forest lies to the west, and the Screaming Wastes to the east. And in fact it often happens that your adventure will begin in one of the Little Kingdoms but eventually take you to one or both of these conveniently close-by but extremely dangerous places.

Nothing about the kingdoms is guaranteed, however. Many young adventurers have come to the Little Kingdoms expecting to make their fortune, only to end up no better off than they were before, or in many cases worse. Strength, good looks, and courage aren’t necessarily going to guarantee you a successful adventure, especially not if you show up with the assumption that because of your gifts you’re entitled to a happy ending. Many bold young men have come here and failed at some task, only to watch their foolish, inexperienced youngest brother succeed. And even a happy ending isn’t necessarily going to stay happy. There have been cases of poor but deserving young men who won the hand of the princess and became king, but who later became obsessed with holding onto power and through their own greed and malice ended up losing their kingdom to other poor but deserving young men. In the Little Kingdoms you can start poor, become a king, and lose it all again. In this way the kingdoms know change while still remaining much the same over the years. When it’s time for knight-apprentices of the Errantry to go on their first solo adventure, they are often sent to the one of the Little Kingdoms. As these are places of relative stability and predictability, an inexperienced knight-in-training is not likely to end up in too much trouble. But then again, in the Perilous Realm nothing is certain. Even the familiar and quiet Little Kingdoms can hold surprises.

Published on October 19, 2012 06:24

October 15, 2012

Rat Hole: a story

We used to feel that nothing ever happened in this town. Every winter it seemed time itself had frozen along with everything else.

From a safe vantage point on the outskirts you could watch people drive into our city and to your eyes they

would appear to have

utterly stopped

moving.

We all secretly knew why things were like this. It was because of the singularity at the heart of our town. The tunnel we called, with our usual self-mockery, the rat hole.

It ran under a railroad crossing at the edge of downtown. It was only an intersection long. But the rat hole was more than just a tunnel, and we all knew it. Eventually, no matter where your business took you, you’d find yourself having to pass through the rat hole to get from one side of the city to the other. And even if you didn’t have to take that route, often you did so anyway, as if the rat hole’s gravity compelled you, like a coin circling a drain, down into its grimy, graffiti-adorned, ill-lit cloaca.

Cars went through the hole, switching on their headlights and narrowly missing each other as they exchanged photons, then came out the other side. It took what … maybe ten seconds to traverse? No big deal, right. And yet every time we passed through the rat hole we knew something had changed.

Coming back out into the daylight, you always felt a moment of doubt about just where you were. As if maybe you'd passed through into an alternate reality. For a moment this utilitarian city seemed exotic. Alien. Even interesting.

In our odd, contradictory way we loved our rat hole. It was an ancient deep space object, for sure, an artifact from the founding of the city or the universe, that made us feel how far-flung we were out here on the prairie from newer, better cities, with soaring overpasses, freeways with multiple lanes, improved, scientifically-planned traffic flow.

Yes, it had to go. We admitted that. We even looked forward to it. The rat hole was a hazard, an eyesore, an embarrassment. So we got rid of it. A couple of weeks, or more likely months, of construction, and it was gone. We thought we didn’t miss it. We liked being able to zip from one side of downtown to the other without that nerve-jarring plunge into rushing glare and gloom.

A lot happens in this town these days. Just like you we’re busy busy busy here. We’re becoming important. There are soaring overpasses, freeways with multiple lanes, improved scientifically-planned traffic flow (okay, that one never really worked out, but apparently it doesn’t anywhere else, either). Now we’re a lot like every other big city. Our patch of the universe emits the same uniform background hum as everyone else's.

We miss our rat hole, though. We do. But who knows what might happen in our future. It may well be that as our city grows too large for itself, its core will collapse under its own density and importance. And then one day we’ll be driving along and we’ll discover there’s a brand new gravity well in our midst that’s tugging us into it. A new rat hole that will fling us through the dark to the far side of ourselves.

From a safe vantage point on the outskirts you could watch people drive into our city and to your eyes they

would appear to have

utterly stopped

moving.

We all secretly knew why things were like this. It was because of the singularity at the heart of our town. The tunnel we called, with our usual self-mockery, the rat hole.

It ran under a railroad crossing at the edge of downtown. It was only an intersection long. But the rat hole was more than just a tunnel, and we all knew it. Eventually, no matter where your business took you, you’d find yourself having to pass through the rat hole to get from one side of the city to the other. And even if you didn’t have to take that route, often you did so anyway, as if the rat hole’s gravity compelled you, like a coin circling a drain, down into its grimy, graffiti-adorned, ill-lit cloaca.

Cars went through the hole, switching on their headlights and narrowly missing each other as they exchanged photons, then came out the other side. It took what … maybe ten seconds to traverse? No big deal, right. And yet every time we passed through the rat hole we knew something had changed.

Coming back out into the daylight, you always felt a moment of doubt about just where you were. As if maybe you'd passed through into an alternate reality. For a moment this utilitarian city seemed exotic. Alien. Even interesting.

In our odd, contradictory way we loved our rat hole. It was an ancient deep space object, for sure, an artifact from the founding of the city or the universe, that made us feel how far-flung we were out here on the prairie from newer, better cities, with soaring overpasses, freeways with multiple lanes, improved, scientifically-planned traffic flow.

Yes, it had to go. We admitted that. We even looked forward to it. The rat hole was a hazard, an eyesore, an embarrassment. So we got rid of it. A couple of weeks, or more likely months, of construction, and it was gone. We thought we didn’t miss it. We liked being able to zip from one side of downtown to the other without that nerve-jarring plunge into rushing glare and gloom.

A lot happens in this town these days. Just like you we’re busy busy busy here. We’re becoming important. There are soaring overpasses, freeways with multiple lanes, improved scientifically-planned traffic flow (okay, that one never really worked out, but apparently it doesn’t anywhere else, either). Now we’re a lot like every other big city. Our patch of the universe emits the same uniform background hum as everyone else's.

We miss our rat hole, though. We do. But who knows what might happen in our future. It may well be that as our city grows too large for itself, its core will collapse under its own density and importance. And then one day we’ll be driving along and we’ll discover there’s a brand new gravity well in our midst that’s tugging us into it. A new rat hole that will fling us through the dark to the far side of ourselves.

Published on October 15, 2012 10:01