Thomas Wharton's Blog, page 5

January 21, 2013

The end of storytelling

In 1936, the German writer and philosopher Walter Benjamin published an essay, “The Storyteller,” in which he lamented that the art of storytelling was dying out in his time, killed in part by an immense flood of information.

In 1936.

“Every morning brings us the news of the globe,” Benjamin wrote, “and yet we are poor in noteworthy stories. This is because no event any longer comes to us without already being shot through with explanation.”

It’s hard to imagine what Benjamin would have thought of our time, when every instant makes available to us more news, facts, factoids, data, images, statistics, lies, and explanations than someone in 1936 could have gathered in a month. It’s astounding that I can carry the libraries and news media of the world around in my pocket, and access them whenever I want to. It’s a miraculous thing. But what happens to my ability to stop and reflect on any of it if I’m consuming information like potato chips, stuffing more of it in every moment?

We still tell each other stories. We still crave stories. The kind of storytelling Benjamin is talking about -- in which people gather around an experienced weaver of worlds, someone who crafts a spellbinding tale with his voice and hands and imagination -- is a rare thing, certainly. Do we still experience the kind of telling which isn’t “shot through with explanation”? The kind of story that keeps some of its secrets, that, as Benjamin beautifully and mysteriously describes it, “preserves and concentrates its strength and is capable of releasing it even after a long time.”

Stories like this are surely still being told, in books and film and even by word of mouth. But how can we give them our whole attention when they get crowded out a moment later by more stories, more texts and facts and babble? How can a storytelling be a special event when countless stories are available, at our fingertips, whenever we want them? Are we still able, or willing, to let a powerful story live and grow in us slowly, over days, months, years?

Maybe the problem isn't so much one of information, as Benjamin lamented, but one of too many stories.

In 1936.

“Every morning brings us the news of the globe,” Benjamin wrote, “and yet we are poor in noteworthy stories. This is because no event any longer comes to us without already being shot through with explanation.”

It’s hard to imagine what Benjamin would have thought of our time, when every instant makes available to us more news, facts, factoids, data, images, statistics, lies, and explanations than someone in 1936 could have gathered in a month. It’s astounding that I can carry the libraries and news media of the world around in my pocket, and access them whenever I want to. It’s a miraculous thing. But what happens to my ability to stop and reflect on any of it if I’m consuming information like potato chips, stuffing more of it in every moment?

We still tell each other stories. We still crave stories. The kind of storytelling Benjamin is talking about -- in which people gather around an experienced weaver of worlds, someone who crafts a spellbinding tale with his voice and hands and imagination -- is a rare thing, certainly. Do we still experience the kind of telling which isn’t “shot through with explanation”? The kind of story that keeps some of its secrets, that, as Benjamin beautifully and mysteriously describes it, “preserves and concentrates its strength and is capable of releasing it even after a long time.”

Stories like this are surely still being told, in books and film and even by word of mouth. But how can we give them our whole attention when they get crowded out a moment later by more stories, more texts and facts and babble? How can a storytelling be a special event when countless stories are available, at our fingertips, whenever we want them? Are we still able, or willing, to let a powerful story live and grow in us slowly, over days, months, years?

Maybe the problem isn't so much one of information, as Benjamin lamented, but one of too many stories.

Published on January 21, 2013 06:47

January 18, 2013

Popular posts from the past: Ogre

Traveling in the Perilous Realm you’re likely, sooner or later, to meet ogres. They have become more and more familiar denizens of Story these days, no doubt largely as a result of computer and roleplaying games like World of Warcraft, in which they appear quite often. In these games, and the guidebooks and manuals that have spun off from them, ogres have been catalogued by way of various species, tribes, races, etc. You can, for example, encounter an “ogre mage,” which is surprising, given that ogres are traditionally thought of as brutish hateful creatures without much in the way of brains. Rarely (if ever) in stories does a hero go to consult a wise old ogre.

The word ogre itself is interesting. Looking into its etymology, one finds that the word first appears in French literature, in a 12th century poem about the Aruthurian knight Percival, where these lines appear:

et s'est escrit que il ert ancoreque toz li reaumes de Logres,qui ja dis fu la terre as ogres,ert destruite par cele lance …

Which translates roughly to something like: “and there will come a time / when the kingdom of Logres [England], / which was once the land of ogres / shall be destroyed by that spear …”

It almost seems likely the poet invented the word ogre in order to find something to rhyme with an odd word like Logres. From there, however, the word ogre shows up more and more frequently in poems and stories through the ages, usually to describe some sort of large, savage, nasty being, somewhere in size between a goblin and a giant.

I used to wonder why there were no ogres in Tolkien’s books, only trolls, until I discovered that his word for goblin, orc, may have been derived from the Italian word for ogre, orco, which may itself come from a far older word for some sort of evil creature. So he didn't want both orcs and ogres in his stories if they're really the same thing, at least etymologically. As usual with Professor Tolkien, it was an interesting old word that sparked his imagination and led to the creation of a new creature.

Sometimes that's how the realm of Story grows: the word comes first, then something has to be imagined to fit it.

Published on January 18, 2013 05:43

January 15, 2013

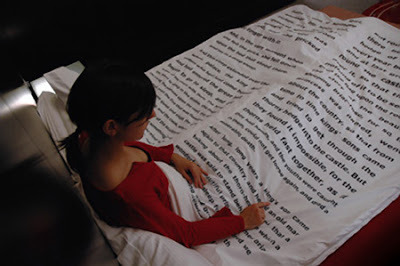

Night fiction

Sometimes when people find out I’m a writer of fiction they say to me, “I can’t write.” Or “I can’t tell a story to save my life.”

When I hear that I sometimes like to remind people that we’re all storytellers. We all invent incredibly rich, fantastical tales … every night.

We all become storytellers when we dream.

Thanks to Freud and Joseph Campbell we’ve gotten used to the idea that a dream is about oneself. That the characters in our dreams are really aspects of ourselves and that if a dream has any meaning at all, it’s a psychological or spiritual meaning about something going on within us.

There may be a lot of truth to that, but it obscures the equally interesting fact that dreams are also stories. Most dreams may be stories that don’t make a lot of rational sense, but when we wake up and remember them, we remember them as narratives. Rather than looking for the meaning in a dream (as students are taught to extract the theme from a work of literature), it might be worthwhile to just pay attention to the story itself. Where did my dream take place? Who were the characters? Did it have a beginning, or an ending? Was it like any other stories I know? Did I enjoy the story? Did it move me?

Before we go hunting for meaning we might ask ourselves: what kinds of stories do my dreams tell?

In our dreams we take the appearance and personality of people in our waking life, and we mix and remix these elements to create dream-people who are like the people we know. And yet they are also fictions, creations of our dreaming imagination. These dream-people live brief lives -- they’re woven into existence only for the few moments of the dreaming, and when the dream ends or we wake up, they’re unwoven again. They have only these brief, ghostly lives, but as the Swedish poet Tomas Tranströmer writes, “the dreamt-of people are more numerous than us.”

We weave these casts of characters, these novels, plays, fictions, poems, movies, every night. And then when we wake up, most of us go back to thinking that we aren’t creative in that way. That’s it up to someone else to be the storyteller.

When I hear that I sometimes like to remind people that we’re all storytellers. We all invent incredibly rich, fantastical tales … every night.

We all become storytellers when we dream.

Thanks to Freud and Joseph Campbell we’ve gotten used to the idea that a dream is about oneself. That the characters in our dreams are really aspects of ourselves and that if a dream has any meaning at all, it’s a psychological or spiritual meaning about something going on within us.

There may be a lot of truth to that, but it obscures the equally interesting fact that dreams are also stories. Most dreams may be stories that don’t make a lot of rational sense, but when we wake up and remember them, we remember them as narratives. Rather than looking for the meaning in a dream (as students are taught to extract the theme from a work of literature), it might be worthwhile to just pay attention to the story itself. Where did my dream take place? Who were the characters? Did it have a beginning, or an ending? Was it like any other stories I know? Did I enjoy the story? Did it move me?

Before we go hunting for meaning we might ask ourselves: what kinds of stories do my dreams tell?

In our dreams we take the appearance and personality of people in our waking life, and we mix and remix these elements to create dream-people who are like the people we know. And yet they are also fictions, creations of our dreaming imagination. These dream-people live brief lives -- they’re woven into existence only for the few moments of the dreaming, and when the dream ends or we wake up, they’re unwoven again. They have only these brief, ghostly lives, but as the Swedish poet Tomas Tranströmer writes, “the dreamt-of people are more numerous than us.”

We weave these casts of characters, these novels, plays, fictions, poems, movies, every night. And then when we wake up, most of us go back to thinking that we aren’t creative in that way. That’s it up to someone else to be the storyteller.

Published on January 15, 2013 06:19

January 10, 2013

A good night's story

The other day someone mentioned on Facebook that they were having trouble getting to sleep. They were going through the whole “lying in bed tossing and turning, thoughts going around in circles” thing.

My suggestion was this:

Before going to bed, tell yourself a story. It doesn’t have to be a long story, and it doesn’t have to be a great one. But it should have one thing: a satisfying resolution. You can write the story out, or speak it to yourself, that doesn’t matter. And it can be a story about pretty much anything, but it’s best if it’s not a story about you (because then the temptation will be to narrate whatever’s bothering you right now and may be the cause of your insomnia, which probably won’t help).

What I do is tell myself a traditional-style tale. “There once was a boy who set out to find the princess of the moon, for he heard she was very beautiful…” That sort of thing. I don’t have a plot in mind when I start. I just let the story unfold, out of all the traditional elements I’ve absorbed from other stories all my life. Encounters, mishaps, magical objects, threats … I don’t worry about whether it’s a good story that anyone else would want to hear. I just tell it, with one idea in mind: that eventually it will have to resolve into a satisfying ending.

If you’re not a writer or someone who tells stories, you’re probably thinking there’s no way you can do this. Actually, in my view, we’ve all got Story deep within us. We’re all storytellers. When we were little someone told us stories, and we continue to watch countless stories unfold on TV and in movies and books all our lives.

If you honestly don’t think you can tell yourself a story, or you’re just too tired to try at the end of the day, then trying reading a traditional tale (out loud is best) or watching a show with a satisfying resolution. Or you could even ask someone else to tell you a story.

The reasoning behind this insomnia cure (which has worked for me many times) is that the mind craves stories, and it craves resolution. Usually the reason we can’t get to sleep is that we feel there’s still something unfinished, something we haven’t completed, even if sometimes we don’t consciously acknowledge what that unfinished thing is. Instead of lying there ruminating over the day past and the day to come, give your mind the satisfaction of a story that has an ending.

This is why little kids beg for a story at the end of the day. They want to be taken on a journey from somewhere to somewhere. At the end of a rich, chaotic, busy day of being a kid, full of the usual random bombardment of experience and sensation, they want the world to fall into a neat orderly pattern that wraps it all up. And adults are really no different.

Published on January 10, 2013 07:10

January 7, 2013

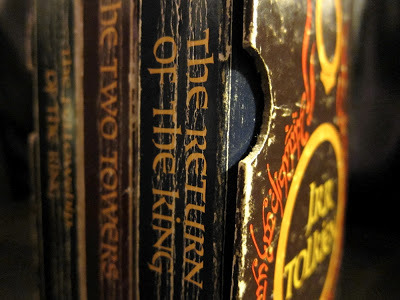

How J R R Tolkien ruined fantasy

How J R R Tolkien ruined fantasy

(What I learned from Tolkien, part 3)

Ruined it for me, I mean. For a good long while. After I read The Lord of the Rings at the age of eleven or twelve, I went looking for fantasy novels that could equal Tolkien’s great work in scope and and quality of writing and convincingness.

There were none.

I wanted books that held entire worlds between their covers. Worlds so authentic and real and detailed that I could believe in them and inhabit them, at least in my imagination. I tried novel like Terry Brooks’ Sword of Shannara and found it, despite the lovely Tolkienesque artwork of the Brothers Hildebrandt gracing its pages, vastly inferior to the work it tried so desperately to emulate.

It’s ironic that the first ground-breaking work of contemporary genre fantasy was also the greatest example of it, and has remained unmatched by anyone since.

Eventually I found what I was looking for -- books that were entire worlds -- in Frank Herbert’s Dune series. And from there, still looking for that kind of depth and richness, I went on to read immense novels like War and Peace. It was a long time before I returned to reading fantasy, and when I did, I still read very little of it, because only very little of it seemed good to me anymore.

When I started working on my own fantasy trilogy, at my daughter’s request, I knew that I wanted the world I was creating to have depth and authenticity. So I began slowly, and for the first couple of years of the project, did little more than draw maps, and write histories of the realm I wanted to bring into being. That is, I didn’t start by writing a story but by creating a world for the story to happen in.

And that even included an attempt to create a language, called Arqan, based on a mingling of Finnish and Inuktitut, for one of the peoples in my imaginary world to speak. I abandoned that made-up language at a certain point, when it became clear that most of the the story wasn’t going to take place in the far north, as I’d originally thought. It was a very “northern” sounding language, at least to my ears, but there was no longer a character in the story to speak it. Well, I can save it for another book, perhaps.

Anyhow, Tolkien spoiled fantasy for me because his work taught me not to devour books one after another but to read them with care and love and attention, to demand a lot of them, more than most fantasy novels of the time could deliver. To challenge myself as a reader, and then as a writer, to push beyond what I knew and was comfortable with.

Illustration: detail from a painting by Cor Blok, showing Gandalf telling the story of his battle with the Balrog to Aragorn, Legolas, and Gimli. In Blok's inspired rendering, Gandalf's body becomes the mountain on which the battle and its aftermath (his resuce by the eagle) takes place.

Published on January 07, 2013 07:38

January 4, 2013

Things not seen and places not visited

<!-- /* Font Definitions */ @font-face {font-family:"MS 明朝"; mso-font-charset:78; mso-generic-font-family:auto; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-536870145 1791491579 18 0 131231 0;} @font-face {font-family:"MS 明朝"; mso-font-charset:78; mso-generic-font-family:auto; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-536870145 1791491579 18 0 131231 0;} @font-face {font-family:Cambria; panose-1:2 4 5 3 5 4 6 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:auto; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-536870145 1073743103 0 0 415 0;} /* Style Definitions */ p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal {mso-style-unhide:no; mso-style-qformat:yes; mso-style-parent:""; margin:0cm; margin-bottom:.0001pt; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:12.0pt; font-family:Cambria; mso-ascii-font-family:Cambria; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-fareast-font-family:"MS 明朝"; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-fareast; mso-hansi-font-family:Cambria; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi;} .MsoChpDefault {mso-style-type:export-only; mso-default-props:yes; font-family:Cambria; mso-ascii-font-family:Cambria; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-fareast-font-family:"MS 明朝"; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-fareast; mso-hansi-font-family:Cambria; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi;} @page WordSection1 {size:612.0pt 792.0pt; margin:72.0pt 90.0pt 72.0pt 90.0pt; mso-header-margin:35.4pt; mso-footer-margin:35.4pt; mso-paper-source:0;} div.WordSection1 {page:WordSection1;} </style> <br /><div class="MsoNormal" style="line-height: 150%; text-align: justify; text-justify: inter-ideograph;"><br /></div><div class="separator" style="clear: both; text-align: center;"><a href="http://2.bp.blogspot.com/-vend-ELyjx4..." imageanchor="1" style="margin-left: 1em; margin-right: 1em;"><img border="0" height="640" src="http://2.bp.blogspot.com/-vend-ELyjx4..." width="380" /></a></div><div class="separator" style="clear: both; text-align: center;"></div><div class="MsoNormal" style="line-height: 150%; text-align: center;"><br /></div><div class="MsoNormal" style="line-height: 150%; text-align: justify;"><div style="text-align: center;"><br /></div><div style="text-align: center;"><span style="font-size: large;">(What I learned from Tolkien, part 2)</span></div><br /><br /></div><div class="MsoNormal" style="line-height: 150%; text-align: justify;"><span style="font-size: large;"><span style="font-family: "Times New Roman"; line-height: 150%;">I first read the Lord of the Rings when I was eleven or twelve, and like so many other readers, I didn’t just suspend disbelief, I actively believed. I lived and breathed Tolkien’s imaginary world. When I finished the book I didn’t want to leave it.</span></span></div><div class="MsoNormal" style="line-height: 150%; text-align: justify;"><br /></div><div class="MsoNormal" style="line-height: 150%; text-align: justify;"><span style="font-size: large;"><span style="font-family: "Times New Roman"; line-height: 150%;">In my last post I talked about the importance of names in <i>The Lord of the Rings</i>. Most of the important people, places, and things in the book have more than one name, and this lends a greater sense of authenticity and “three-dimensionality” to the imaginary world. </span></span></div><div class="MsoNormal" style="line-height: 150%; text-align: justify;"><br /></div><div class="MsoNormal" style="line-height: 150%; text-align: justify;"><span style="font-size: large;"><span style="font-family: "Times New Roman"; line-height: 150%;">Another key factor in creating the illusion of truth and depth is the mention of people we never meet, and places that never get visited. One much-discussed example is Saruman’s mention of the “five wizards” in <i>The Two Towers. </i>Up to that point we know only about the wizards Saruman and Gandalf, and now we’re told there are five (only <i>five</i>?). That’s all the detail we get about them in the book, but it’s one of the many moments in which a reader’s sense of this imaginary world expands just a tiny bit. There’s more here to know, it seems. There’s an entire world beyond the unfolding of the story. A world of places, characters, and events that we can only glimpse through these tantalizing hints, and which is thus left to our imagination to fill in and wonder about. We're drawn to explore in directions that the story itself doesn't go. More than just about any author, Tolkien grants our restless imagination the freedom to take these side-trips. </span></span></div><div class="MsoNormal" style="line-height: 150%;"><br /></div><div class="MsoNormal" style="line-height: 150%; text-align: justify;"><span style="font-size: large;"><span style="font-family: "Times New Roman"; line-height: 150%;">Tolkien employs a similar strategy with his dark lord, Sauron. We never actually <i>see</i> him, so that he remains for the reader mysterious, shadowy figure of enormous menace. Again, we have to use our imaginations to fill in what isn’t told, and that is far more effective and convincing than being told and shown everything (which is why the appearance of Sauron in the film version of <i>The Lord of the Rings</i> as an armor-clad giant is so disappointing, and why so many horror movies are scary only until<i> </i> the moment that the creature is shown to us).</span></span></div><div class="MsoNormal" style="line-height: 150%;"><br /></div><div class="MsoNormal" style="line-height: 150%; text-align: justify;"><span style="font-size: large;"><span style="font-family: "Times New Roman"; line-height: 150%;">In one brief passage, near the end of the book, when Frodo puts on the ring, Tolkien shift’s the point of view of the story to Sauron himself. Here again, we don’t actually get to <i>see</i> the dark lord, but instead we get the deliciously ironic pleasure of seeing what he sees, which is that for all his power and cunning, he has been a complete fool:</span></span></div><div class="MsoNormal" style="line-height: 150%; text-align: justify;"><br /></div><div class="MsoNormal" style="line-height: 150%;"><span style="font-size: large;"><span style="font-family: "Times New Roman"; line-height: 150%;">“… the magnitude of his own folly was revealed to him in a blinding flash, and all the devices of his enemies were at last laid bare. Then his wrath blazed in consuming flame, but his fear rose like a vast black smoke to choke him. For he knew his deadly peril and the thread upon which his doom now hung.”</span></span></div><div class="MsoNormal" style="line-height: 150%;"><br /></div><div class="MsoNormal" style="line-height: 150%;"><span style="font-size: large;"><span style="font-family: "Times New Roman"; line-height: 150%;">It’s a brilliant moment because it gives us a look inside the mind of this shadowy figure, while still allowing him to remain vague and mysterious.</span></span></div><div class="MsoNormal" style="line-height: 150%;"><br /></div><div class="MsoNormal" style="line-height: 150%;"><span style="font-size: large;"><span style="font-family: "Times New Roman"; line-height: 150%;">It’s a classic example of the truth that a writer needs to keep some secrets from the reader. I have a <a href="https://www.acaciart.com/stories/arch..." target="_blank">“talking stick”</a> that I sometimes bring with me when I visit schools as a writer. It’s actually part of an old walking stick that broke, and I’ve adorned it with a number of objects that represent important truths about storytelling. Whoever’s turn it is to tell a story gets to hold the talking stick. One of these items on the stick a small black pouch. “What’s inside it?” the kids sometimes ask me, but I don’t tell them. The bag represents all of the things that a storyteller <i>doesn’t </i>show or tell. What’s in the bag is half the secret of a story’s power.</span></span></div><div class="MsoNormal" style="line-height: 150%;"><br /></div><div class="MsoNormal" style="line-height: 150%;"><br /></div><div class="MsoNormal" style="line-height: 150%;"><span style="font-size: large;"><span style="font-family: "Times New Roman"; line-height: 150%;"><span style="font-size: small;">Illustration: detail from "The Blue Wizards Journeying into the East" by Ted Nasmith</span></span></span></div><div class="MsoNormal" style="line-height: 150%;"><br /></div><div class="MsoNormal" style="line-height: 150%;"><br /></div><div class="MsoNormal" style="line-height: 150%;"><br /></div><div class="blogger-post-footer"><img alt="StumbleUpon" src="http://www.stumbleupon.com/images/stu..." border="0" /></div>

Published on January 04, 2013 06:57

December 31, 2012

What I learned from Tolkien

Last month I posted about thirty novels that have been important to me as a reader and a writer. The Lord of the Rings was on my list, but each time I tried to boil down my indebtedness to this book in a single post, I discovered there was more I wanted to say about it. So in the end I decided to save Tolkien’s masterpiece for later, and address it in a series of posts rather than just one. Today is the first installment of “What I learned from Tolkien”, and I want to start with names.

One thing a reader of The Lord of the Ringsnotices pretty quickly is that most of the important people, places and things in the story have multiple names. Take Aragorn for example. He’s known to different people at different times as Strider, Aragorn son of Arathorn, Estel, and Elessar. And we learn he probably went by other names during his long years of errantry.

Gandalf, too, has a pocketful of names. Even his sword has at least two names. It’s Glamdring, which translates as Foe-Hammer, and it’s a sword that once belonged to Turgon, King of Gondolin. The mines of Moria are also known as Khazad-Dum, the Dwarrowdelf, and Hadhodrond. Frodo himself, who begins as an “unimportant” hobbit, begins to collect different names as the story goes along: Mr Underhill, the Master (to Gollum), and the Ringbearer.

One of the effects on a reader of all these names is to increase the credibility and authenticity of Tolkien’s imaginary world. We believe in these people and places a little more strongly with each name they’re given because the names bring with them layers of meaning and hints of backstory. The characters gain depth and complexity not so much from realistic psychological details as from the meanings and history behind their names. (But the multiple names do add a kind of “realism” to the story, as well, because we all have different names at different times in our lives and careers. I was “Tommy” as a child, I’m “Thomas” as a writer, and to my kids I’m “Dad” or “hey, you.”).

As a writer of fantasy I’ve learned many things from Tolkien, and one of the most crucial lessons has been the importance of names. You’ve got to find a good, strong name for a character, a name with resonance and a hint of who they are (or what they might become). But finding that one name isn’t enough. Your characters are going to need other names as the story progresses, names that mark important moments of their adventures, of their passage through life.

Giving characters and places multiple names is a strategy that contemporary editors frown on. They worry that readers may be confused by all the different names. Fortunately for us all, Tolkien’s editors were wiser than that. They must have understood that the real wizardry of the novel was in the beauty and power of its language, and that much of that power was carried in names.

Published on December 31, 2012 07:37

December 28, 2012

Stories as mirrors

I received a strange and wonderful letter the other day, from two readers in Italy named Alberto and Elisa. They had read the first book in my trilogy, The Shadow of Malabron (in Italian, L’ombra di Malabron) and wanted to let me know what the book had meant to them. It seems that the story of Will and Rowen reflects their own lives in certain coincidental ways. They told me that Alberto shares the same birthday with Will Lightfoot, and that as he grew up Alberto saw “his dreams break into a thousand pieces like mirrors” much in the way that Will’s life seems to have shattered after his mother’s death (the tree hung with shards of mirror becomes a symbol in the book of that event).

Alberto and Elisa met by chance much the same way that Will and Rowen do in the novel, and they even felt that my description of these characters resembles them.

I’ve had similar experiences in the past, in which readers told me that incidents or characters in my books mirror their own lives. After I published my first novel, Icefields, I met a man who had fallen into a crevasse on a glacier, much as my main character, Doctor Byrne, does in the book. And the result of this accident was a profound change in the life of this man. Much as it was for Byrne in the novel. Talking to this man I had the strange feeling that my own fictional character had come to life before me.

As a reader myself I’ve had such experiences, too, finding deep and surprising connections between my own life and certain books. I don’t know what to think about these kinds of coincidences and connections, other than that they must have much to do with Story itself, and how our own lives are woven of stories (the stories we tell ourselves, or are told by others, or find ourselves in, the stories of history and culture and religion…). As Elisa said in her message, “the universe works with us in ways that the human mind cannot even dream.” I believe that’s true. And I believe that stories are one of the ways that we attempt to dream the universe and understand how it works.

I'm still putting the finishing touches on the third book of the trilogy, and now I find myself in the strange situation of wondering whether the adventures of Will and Rowen in Book 3 will in some way continue to mirror the story of these two readers.

Thank you for the magical letter, Alberto and Elisa.

Alberto and Elisa met by chance much the same way that Will and Rowen do in the novel, and they even felt that my description of these characters resembles them.

I’ve had similar experiences in the past, in which readers told me that incidents or characters in my books mirror their own lives. After I published my first novel, Icefields, I met a man who had fallen into a crevasse on a glacier, much as my main character, Doctor Byrne, does in the book. And the result of this accident was a profound change in the life of this man. Much as it was for Byrne in the novel. Talking to this man I had the strange feeling that my own fictional character had come to life before me.

As a reader myself I’ve had such experiences, too, finding deep and surprising connections between my own life and certain books. I don’t know what to think about these kinds of coincidences and connections, other than that they must have much to do with Story itself, and how our own lives are woven of stories (the stories we tell ourselves, or are told by others, or find ourselves in, the stories of history and culture and religion…). As Elisa said in her message, “the universe works with us in ways that the human mind cannot even dream.” I believe that’s true. And I believe that stories are one of the ways that we attempt to dream the universe and understand how it works.

I'm still putting the finishing touches on the third book of the trilogy, and now I find myself in the strange situation of wondering whether the adventures of Will and Rowen in Book 3 will in some way continue to mirror the story of these two readers.

Thank you for the magical letter, Alberto and Elisa.

Published on December 28, 2012 07:41

December 21, 2012

To become a hero

To become a hero, first you need a story.

That’s the unacknowledged message of almost every story we encounter when we’re young. Where do you find heroes? In stories. Even in the real world, when we’re told that someone is a hero, we want to know: what did he do? What’s the story?

By “hero” I don’t just mean someone who wins the championship game for his team or rescues people from a burning building. I mean it more in the sense that Joseph Campbell often used the word when he talked about the hero’s journey as a pattern embedded deep in the human psyche. That is, a hero is someone who discovers the potential within herself and sets out to fulfill it, no matter how difficult the journey. And that potential can be anything. Athletic. Intellectual. Creative. The ability to bring people together. The desire to help others. It doesn't have to be something "great" in the eyes of the world. What matters is that it's a path, a story, that you've chosen for yourself.

To become the hero of your own life, you might start by asking yourself what story you believe you’re in. Whose story is it? Where did it come from? Is it a story you truly feel you belong in? As I mentioned in a previous post, as a kid I tried to live by a story that said in order to become a man I had to be good at sports. Then I discovered that my true potential actually lay somewhere else, and I stopped trying to live someone else’s story.

William Blake wrote “I must create my own system, or be enslav’d by another man’s.”

I would alter that ringing statement slightly:

“I must create my own story, or be enslav’d by another man’s.”

Published on December 21, 2012 09:54

December 19, 2012

The only true story ever told

I think a lot of people, and not just young people, would like to do more with their lives than just eat, sleep, work, and consume. But they’re stuck in an old story about themselves, one that tells them “You are this, and nothing else.” Like Bilbo before Gandalf came along and disturbed his quiet, pleasant little life, they won’t take that step out of the door into the unknown, even if deep down they feel they could become something more, something greater than what they are. So they stick to what they know, and when the need for adventure and purpose grows strong, they watch movies and TV, or play video games. The show or the game feeds the desire to be something more, to be greater than what they are. At least for a while. A game makes it so easy to be a hero … in the game.

On some level we all wish to be the hero of our own life story. But when we turn off the TV or the game, we find ourselves back in a world in which we’re not the hero. Other people are famous, successful, brilliant, and we’re not. Someone else is playing the character we wish we were.

Or we believe there are no real heroes. We grow out of the stories of our childhood, the fairy tales and comforting happy ending stories, and that’s as it should be. One way in which we grow up is by opening our eyes to ways in which real life, our life, isn’t like those stories and is never going to be. But sometimes when people discover how life isn’t like those old stories, they abandon everything the stories have to teach. They come to believe they’re living in a world where the only true, meaningful story ever told is the very short one that goes like this: “Me first.” If you’re not living that story, then you’re a sucker, a fool, a loser.

But I think those old stories really do have something to teach us about how and who we might be, in thisworld. Something greater than "Me first." And come to think of it, so do the movies, TV shows and video games, since so many of them are based on those old stories.

To be continued...

Published on December 19, 2012 07:08