Thomas Wharton's Blog, page 8

November 15, 2012

30 Novels, Day 15: Sleaze, Cruelty, Violence, and Debauchery

30 Novels, Day 15: Crime and Punishment

Fyodor Dostoyevsky

Guest Post by Laurence Miall

I had a friend in high school who was a talented artist. He once showed me a series of black and white illustrations he was working on. Each illustration depicted a scene from a novel by Fyodor Dostoyevsky. I was struck by the intensity and the dark tones of the illustrations. I said to myself, I’m going to check out this Dostoyevsky guy.

Six months after graduating, I was living in France, learning French, babysitting and tutoring for money. I rented a studio apartment in Paris. That sounds somewhat glamorous, and I guess in some respects it was. The Jardin du Luxembourg was close by, with its rows of perfectly-tended flowers, trees standing like sentries in lines, and the centrepiece, a fountain that I could stare at and lose myself in. But my own dwelling was not quite so picturesque. It was only big enough for a thin mattress on the floor, a small stand for my little stereo, and in the corner, a sink. To go to the bathroom, I had to use the shared toilet down the hallway. To take a shower, I had to leave the building entirely and go to the local swimming pool.

Alternating between lying on that uncomfortable mattress, or sitting in the Jardin du Luxembourg, I made my way through Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment. I was immediately drawn to the character of Raskolnikov. Like me, he drifted around rather aimlessly, but he seemed to have very big plans in his head. I didn’t share Raskolnikov’s particularly sinister plan – to murder an old woman – but I nevertheless did often have dark thoughts. I was depressed and lonely. I had been having perfectly innocent dates with a beautiful Portguese girl called Inès, and at one point I said to myself, “She will think I am a mouse if I don’t stir myself to make a move, so I am going to show her I am made of sterner stuff; I am going to attempt to kiss her!” So one evening, in the entrance to the Metro, where I was bidding her farewell after a date, instead of the usual kiss on the cheeks, I went right for her mouth. She turned her head so that I would miss my target. She said, “You are very kind,” and then she hurried away.

So I felt I understood, in some respects, the angst-ridden world of Raskolnikov – his numerous resentments and feelings of unrealized potential. When I pictured where he lived, described by Dostoyevsky as “a closet,” I thought of my own miserable dwelling, where I couldn’t eat at a table, but instead, had to crouch over a cheese and tomato sandwich on a plate, picking the errant crumbs off the brown carpet.

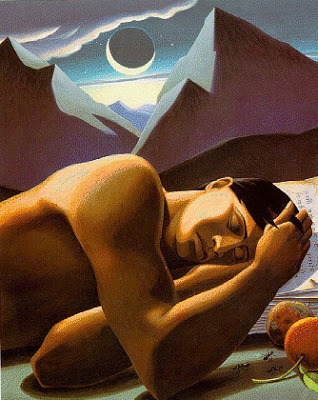

To read Dostoyevsky is to enter a world that often feels like a nightmare, because the drama is rendered in visceral, almost apocalyptic terms, and moreover, Dostoyevsky considers the actual dreams of his characters to be an important part of the action. Crime and Punishment contains two (from my recollection) quite famous dreams: one in which a horse is cruelly beaten to death, and the other about a plague that besets the entire world, making people insane and murderous.

One day, my reading of Dostoyevsky was interrupted by a knock at the door. I opened it. Standing there was a tall man with a metal canister strapped to his back. He asked me if I had a problem with cockroaches. I said, no, I didn’t. Nevertheless, the man was insistent on spraying for cockroaches. A day or two after he’d done his work, I was engrossed in Crime and Punishment to the point where I had delayed going to pee for a long time. I stepped over the remains of my lunch – the usual cheese and tomato sandwich – and I went down the hallway to the toilet. When I returned, I found that a cockroach had crawled onto my plate. He was nonchalantly looking at the remnants of my sandwich.

This was yet more proof that my life was every bit as miserable and awful as I had imagined it to be! The indignities I suffered! Raskolnikov could have been a brother of mine. If had been in Saint Petersburg, Russia, I would have listened to him, just as his faithful friend, Razumikhin, did. As I advanced through the book, I was developing quite a dislike for the character of Porfiry, the investigator that keeps cross-examining Raskolnikov, seeming to delight in tormenting his victim, hinting that he knows what the young man has done, but never saying so. At times, this cat and mouse game made me feel almost unbearably anxious.

D.H. Lawrence reportedly once read an early English translation of this book and reacted with revulsion, calling Dostoyevsky a “snake slithering around in hate.” I can see that. Dostoyevsky remains the most modern of 19th century authors, because he can and will shock you with sleaze, cruelty, violence and debauchery. But he remains the most moral of all authors. He will lead the reader down very dark pathways, but eventually he will always lead you to the light.

Fyodor Dostoyevsky

Guest Post by Laurence Miall

I had a friend in high school who was a talented artist. He once showed me a series of black and white illustrations he was working on. Each illustration depicted a scene from a novel by Fyodor Dostoyevsky. I was struck by the intensity and the dark tones of the illustrations. I said to myself, I’m going to check out this Dostoyevsky guy.

Six months after graduating, I was living in France, learning French, babysitting and tutoring for money. I rented a studio apartment in Paris. That sounds somewhat glamorous, and I guess in some respects it was. The Jardin du Luxembourg was close by, with its rows of perfectly-tended flowers, trees standing like sentries in lines, and the centrepiece, a fountain that I could stare at and lose myself in. But my own dwelling was not quite so picturesque. It was only big enough for a thin mattress on the floor, a small stand for my little stereo, and in the corner, a sink. To go to the bathroom, I had to use the shared toilet down the hallway. To take a shower, I had to leave the building entirely and go to the local swimming pool.

Alternating between lying on that uncomfortable mattress, or sitting in the Jardin du Luxembourg, I made my way through Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment. I was immediately drawn to the character of Raskolnikov. Like me, he drifted around rather aimlessly, but he seemed to have very big plans in his head. I didn’t share Raskolnikov’s particularly sinister plan – to murder an old woman – but I nevertheless did often have dark thoughts. I was depressed and lonely. I had been having perfectly innocent dates with a beautiful Portguese girl called Inès, and at one point I said to myself, “She will think I am a mouse if I don’t stir myself to make a move, so I am going to show her I am made of sterner stuff; I am going to attempt to kiss her!” So one evening, in the entrance to the Metro, where I was bidding her farewell after a date, instead of the usual kiss on the cheeks, I went right for her mouth. She turned her head so that I would miss my target. She said, “You are very kind,” and then she hurried away.

So I felt I understood, in some respects, the angst-ridden world of Raskolnikov – his numerous resentments and feelings of unrealized potential. When I pictured where he lived, described by Dostoyevsky as “a closet,” I thought of my own miserable dwelling, where I couldn’t eat at a table, but instead, had to crouch over a cheese and tomato sandwich on a plate, picking the errant crumbs off the brown carpet.

To read Dostoyevsky is to enter a world that often feels like a nightmare, because the drama is rendered in visceral, almost apocalyptic terms, and moreover, Dostoyevsky considers the actual dreams of his characters to be an important part of the action. Crime and Punishment contains two (from my recollection) quite famous dreams: one in which a horse is cruelly beaten to death, and the other about a plague that besets the entire world, making people insane and murderous.

One day, my reading of Dostoyevsky was interrupted by a knock at the door. I opened it. Standing there was a tall man with a metal canister strapped to his back. He asked me if I had a problem with cockroaches. I said, no, I didn’t. Nevertheless, the man was insistent on spraying for cockroaches. A day or two after he’d done his work, I was engrossed in Crime and Punishment to the point where I had delayed going to pee for a long time. I stepped over the remains of my lunch – the usual cheese and tomato sandwich – and I went down the hallway to the toilet. When I returned, I found that a cockroach had crawled onto my plate. He was nonchalantly looking at the remnants of my sandwich.

This was yet more proof that my life was every bit as miserable and awful as I had imagined it to be! The indignities I suffered! Raskolnikov could have been a brother of mine. If had been in Saint Petersburg, Russia, I would have listened to him, just as his faithful friend, Razumikhin, did. As I advanced through the book, I was developing quite a dislike for the character of Porfiry, the investigator that keeps cross-examining Raskolnikov, seeming to delight in tormenting his victim, hinting that he knows what the young man has done, but never saying so. At times, this cat and mouse game made me feel almost unbearably anxious.

D.H. Lawrence reportedly once read an early English translation of this book and reacted with revulsion, calling Dostoyevsky a “snake slithering around in hate.” I can see that. Dostoyevsky remains the most modern of 19th century authors, because he can and will shock you with sleaze, cruelty, violence and debauchery. But he remains the most moral of all authors. He will lead the reader down very dark pathways, but eventually he will always lead you to the light.

Published on November 15, 2012 06:50

November 14, 2012

30 Novels, day 14: A novel by Borges

30 Novels, day 14: Jorge Luis Borges, The Golden Thread

In the acknowledgements to my novel Salamander (a book about the creation of an infinite book) I mention that my work was inspired by “The Book of Sand,” a short story by the great Argentinian fabulist Jorge Luis Borges.

Then I added “The novel Borges never wrote was also a great inspiration.”

I’ve always been fascinated by books that don’t exist. Fictional books, as opposed to books of fiction. (When my wife and I visited her aunt and uncle in Ireland, I looked at the uncle’s shelf of books and noticed it contained only works of engineering, history, and biography. I asked him if he had any novels and he said proudly, “I’ve never read a fictitious book in me life.” I was tempted to tell him, “Neither have I.”)

Literature is full of mentions of imaginary books. Nabokov’s Pale Fire. The novels of Umberto Eco. J. R. R. Tolkien goes to great lengths to convince us his Lord of the Rings is actually a retelling and translation of an earlier volume of lore, The Red Book of Westmarch, which contained much that has been lost and forgotten.

But Borges is the undisputed master of the imaginary book. The story goes that he had trouble writing fiction until he hit upon the idea of adapting the genre of the literary review to write about books that don’t exist.

And yet he never wrote a novel. Perhaps it was because in his fiction he’d already described the ideal books he wanted to write, or at least to read.

So, in homage to Borges, I imagine that his unwritten novel actually does exist, and that I am reading it. I’ve been reading it for years. I haven’t finished it yet. Perhaps it’s an infinite book and I never can finish it. But I can tell you about some of the things it contains. There are mirrors in it, and a labyrinth, of course, although this labyrinth looks invitingly like a straight line. There are stories within stories within stories. Are they all telling the same story? There is a creature haunting this novel, a fabulous, elusive bird-beast whose wings make the sound of pages being riffled somewhere else in the book.

Sometimes I imagine Borges’ unwritten novel is about a writer who begins to realize that the book he’s been working on and can’t finish is actually a book that contains everything. It is the world, and he himself is a minor character in it, a nobody at the fringes of the story. And yet somewhere else in this vast book is the murderer who killed his beloved wife. Can he track the murderer down before the book ends? Can he change the story and turn this book into his book, this world into his world?

In the acknowledgements to my novel Salamander (a book about the creation of an infinite book) I mention that my work was inspired by “The Book of Sand,” a short story by the great Argentinian fabulist Jorge Luis Borges.

Then I added “The novel Borges never wrote was also a great inspiration.”

I’ve always been fascinated by books that don’t exist. Fictional books, as opposed to books of fiction. (When my wife and I visited her aunt and uncle in Ireland, I looked at the uncle’s shelf of books and noticed it contained only works of engineering, history, and biography. I asked him if he had any novels and he said proudly, “I’ve never read a fictitious book in me life.” I was tempted to tell him, “Neither have I.”)

Literature is full of mentions of imaginary books. Nabokov’s Pale Fire. The novels of Umberto Eco. J. R. R. Tolkien goes to great lengths to convince us his Lord of the Rings is actually a retelling and translation of an earlier volume of lore, The Red Book of Westmarch, which contained much that has been lost and forgotten.

But Borges is the undisputed master of the imaginary book. The story goes that he had trouble writing fiction until he hit upon the idea of adapting the genre of the literary review to write about books that don’t exist.

And yet he never wrote a novel. Perhaps it was because in his fiction he’d already described the ideal books he wanted to write, or at least to read.

So, in homage to Borges, I imagine that his unwritten novel actually does exist, and that I am reading it. I’ve been reading it for years. I haven’t finished it yet. Perhaps it’s an infinite book and I never can finish it. But I can tell you about some of the things it contains. There are mirrors in it, and a labyrinth, of course, although this labyrinth looks invitingly like a straight line. There are stories within stories within stories. Are they all telling the same story? There is a creature haunting this novel, a fabulous, elusive bird-beast whose wings make the sound of pages being riffled somewhere else in the book.

Sometimes I imagine Borges’ unwritten novel is about a writer who begins to realize that the book he’s been working on and can’t finish is actually a book that contains everything. It is the world, and he himself is a minor character in it, a nobody at the fringes of the story. And yet somewhere else in this vast book is the murderer who killed his beloved wife. Can he track the murderer down before the book ends? Can he change the story and turn this book into his book, this world into his world?

Published on November 14, 2012 09:10

November 13, 2012

30 Novels, day 13: "Strange and harrowing must be his story."

30 Novels, day 13: Mary Shelley: Frankenstein

This novel was a complete surprise to me when I first read it, probably around age 11 or 12. The monster in the book was not the grunting moron that he had been turned into by movies and TV. In the book he learns how to speak, and then to read. He tells his own story. He even reads novels and poetry, and gives his thoughts and opinions on them.

Eventually he turns to thoughts of hatred and revenge, and sets out to find and destroy his creator, but I could feel for this monster. I could care about his fate. He was a thinking, feeling being.

The novel was also a surprise to me because the story is so preposterous. The book has great thrills and chills (and a wonderful scene set on a glacier), but the characters do such ridiculous, idiotic things. Case in point: the monster threatens Victor Frankenstein with the words, “I will be with you on your wedding night.” Rather than break off his engagement for the sake of his bride-to-be, Victor instead decides to hasten the day of his marriage to Elizabeth.

Then, on their wedding night, Victor leaves his young bride alone in their hotel room in order to search the corridors and grounds for his enemy, thus breaking the one cardinal rule that characters in horror stories have been breaking ever since: always stay together.

The novel is contrived, clumsy, even boring at times. It’s an annoying, frustrating read. The story of Mary Shelley’s own life, come to think of it, would make a better novel (she was nineteen when she wrote this book!).

But the novel stuck with me, despite its flaws, as it has stuck with countless other readers through the years. Like Kafka’s The Castle, it has a quality of inevitability: someone had to write this book. This story had to be.

Published on November 13, 2012 07:03

November 12, 2012

30 Novels, day 12: Dream novel

30 Novels, Day 12: The CastleFranz Kafka

There are some books that seem inevitable. Books that had to be written. These are the stories that touch on some aspect of existence that everyone in the world had experienced but no one had ever put into words before. No one had translated this experience into story.

The Castle is told as a dream. A nightmare everyone has had. The one where we’re wandering around trying to accomplish something and we meet obstacles at every turn. We struggle hopelessly against these obstacles, and sometimes we struggle against ourselves. Even our body refuses to obey us in the world of the dream. A walk across the street becomes an unending, agonizing trudge. Something that should not be impossible proves to be so.

K, the surveyor, arrives on a snowy night in an unnamed village. He’s been hired to do surveying (or has he?) by someone in the Castle. He wants to speak to those who have hired him, up in the Castle on the hill above the village. But he can never speak to the distant authority in the Castle. He can never reach the Castle. He will struggle throughout the novel to attain his goal, and it will keep receding from him with every effort he makes.

Even K’s identity is in doubt as the story progresses. He tells everyone he was hired by the Castle to do survey work, but after a while his statements start to ring false. Just as, in a dream, we sometimes find ourselves in a role or career that’s nothing but a fiction of the dream-plot. We’ve never been an airline pilot or a detective, and some part of us knows this, even as we pretend, for the sake of the dream-story, that it’s true.

Kafka’s novel is unfinished, but that fact itself makes this book even more dreamlike. Most of our dream-stories have no resolution, no satisfying denouement. They don’t end -- they break off. Just like

Published on November 12, 2012 09:49

November 11, 2012

30 Novels, day 11: War children

30 Novels, day 11: Carrie’s War by Nina Bawden

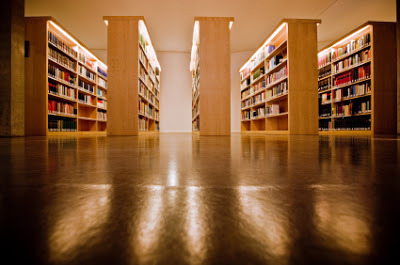

I read this novel when I was in grade 5 or 6. Unlike the stern but fair librarian at the public library downtown, the librarian at my school was snappy and unpleasant. The library she guarded like a bulldog was a tiny little room, and maybe that cramped space had cramped her soul, I don’t know.

We were given time during the day to go to the library and pick out a book. We’d all hurry to the library because it was a break from the classroom, but long after my classmates had picked something out and gone, I would linger in that little room, going up and down the aisles and looking at all the books.

After a short time the librarian would grumpily shoo me out. “You’re just hanging around in here to get out of doing your schoolwork,” she snapped at me once. I thought that was so unfair. I actually wanted to be there. I wanted to be with the books.

I haven’t read Bawden's novel again since those days and I don’t remember a lot about it, nor do I have a copy on my shelves (Remembrance Day has reminded me I really should get a copy and read it again). I do remember that at the time I wasn’t much for what I thought of as “girl’s books,” but this novel had mystery and a cast of odd characters, and it gave me some sense of what it might have been like to a child in wartime. To be separated from one’s family and sent to live in a strange place, even one with the wonderful name of Druid’s Bottom.

I read this novel when I was in grade 5 or 6. Unlike the stern but fair librarian at the public library downtown, the librarian at my school was snappy and unpleasant. The library she guarded like a bulldog was a tiny little room, and maybe that cramped space had cramped her soul, I don’t know.

We were given time during the day to go to the library and pick out a book. We’d all hurry to the library because it was a break from the classroom, but long after my classmates had picked something out and gone, I would linger in that little room, going up and down the aisles and looking at all the books.

After a short time the librarian would grumpily shoo me out. “You’re just hanging around in here to get out of doing your schoolwork,” she snapped at me once. I thought that was so unfair. I actually wanted to be there. I wanted to be with the books.

I haven’t read Bawden's novel again since those days and I don’t remember a lot about it, nor do I have a copy on my shelves (Remembrance Day has reminded me I really should get a copy and read it again). I do remember that at the time I wasn’t much for what I thought of as “girl’s books,” but this novel had mystery and a cast of odd characters, and it gave me some sense of what it might have been like to a child in wartime. To be separated from one’s family and sent to live in a strange place, even one with the wonderful name of Druid’s Bottom.

Published on November 11, 2012 12:41

November 10, 2012

30 novels, day 10: The power of a perfect opening sentence

30 novels, day 10: Gabriel Garcia Marquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

The power of a perfect opening sentence:

“Many years later, as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendia was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice.”

It was a sweltering summer in Edmonton. Sharon and I were living in a small one-bedroom apartment near Whyte Avenue, without air conditioning. I had just discovered Garcia Marquez’ novel set in the steaming Colombian jungle, and it seemed to me I wasn’t just reading the book, I was living it.

One afternoon the apartment was so unbearably stifling that I filled the bathtub with cold water, added all the ice cubes from every ice cube tray we had in the freezer, and climbed in. Brief but blessed relief.

One Hundred Years of Solitude was an astonishing book on every single page, but I kept coming back to that effortless, unforgettable opening sentence, and to the scene, postponed for several pages, when Aureliano finally sees and touches ice for the first time as a boy and says, "It's boiling."

I kept coming back to that block of ice encountered in a tropical jungle, the very first wonder in a book teeming with wonders. Anything in the world, the novel taught me, could be magical when placed in stark contrast, when transformed by a visionary way of seeing.

Around that time I was working on what eventually became my first novel, Icefields, a somewhat magical realist tale set in the Canadian Rockies. In one scene I had my characters sipping tea from delicate china cups while looking out the window of a resort hotel at an avalanche thundering down the mountainside. That moment of contrast, the teacup and the avalanche, I owe to Garcia Marquez.

Published on November 10, 2012 14:51

November 9, 2012

30 novels, day 9: Descriptive of an important proceeding in the life of a reader

30 Novels, day 9: Descriptive of an important proceeding in the life of a reader.

At last, through her own mysterious sense of the ripeness of things, the librarian decided I was old enough.

At last I was allowed to climb up out of the kids’ section in the basement and venture into the tall, narrow, intimidating aisles of the adult section. There were so many books here. I didn’t know what I wanted to read, but I knew one thing: it was time to move beyond the slim children’s novels I had been reading. And so, to inaugurate my career as a grown-up reader, I was going to take out the biggest, fattest book I could find. There was still the hurdle of the librarian, of course. Being allowed into the adult section didn't mean she was going to let me sign out just anything. My choice would have to meet with her approval before she stamped that card and let me pass.

Alliteration has gone out of fashion in book titles these days, but it worked its magic on me then. A title caught my eye and I stopped. This was a pretty thick book, too. Solid and heavy, like a brick. And yet a quick flip-through showed me it had illustrations. So reading a grown-up book didn’t mean I’d have to completely abandon pictures along with the text, which I’d always liked. That was promising. And it looked like a funny book, too, judging by the pictures.

I took it to the librarian, and wonderful to relate, she let me sign it out. The book was The Pickwick Papers, by Charles Dickens.

I didn't like the librarian in those days. The way she stood guard over the books like a cold-eyed sphinx. But now I think she must have been very wise. How do you get kids to want to read? Make the books hard to get at.

I carried Pickwick out of the library, and then he and his hilarious adventures carried me out of myself for days. From there I had to read everything else Dickens had written. And from there all the literature of the world opened up for me.

The book wasn't a brick. It was a door.

Published on November 09, 2012 07:56

November 8, 2012

30 Novels, day 8: Witches in Space

The Witches of Karres by James Schmitz

“It was around the hub of the evening on the planet of Porlumma when Captain Pausert, commercial traveler from the Republic of Nikkeldepain, met the first of the witches of Karres.”

The library in my hometown of Grande Prairie had two floors. The main floor housed the grown-up books and the lower floor was the kids’ section. The librarian took her job very seriously. She would not let you take books from the shelves on the main floor until she judged you were old enough. I know this for a fact because I tried. I wanted to read those grown-up books so badly. I wanted to know what was in them that I wasn’t supposed to read.

I forget what book it was I brought to her counter from the adult section, but she asked me how old I was and then told me to go put it back. She had a deep, loud voice, unusual for a librarian. Her words carried through the library. Defeated, I put the book back and descended once more to the floor for children.

Then one day I found this book. The Witches of Karres, by James Schmitz. I think now that it had been relegated to the kids’ section by mistake. Not that it was particularly adult in theme or content, but it wasn’t really a book for kids, either. I got it past the librarian without incident, and I read it and kind of liked it, even though I didn’t understand a lot of what was going on in it.

That’s probably the reason the book has stuck with me all these years when so many other books haven’t. Because it was so unlike most of the other books I was allowed to read by our vigilant librarian. I’m not sure but I think Witches was probably the very first science fiction novel I ever encountered. This was before Star Wars. There wasn’t a lot out there for me to compare the book to back then. Interestingly, Witches and Star Wars share some similarities of plot and theme, not to mention a penchant for funny, memorable names for all things alien. Sheewash drive, Yango, the Chaladoor, klatha energy…. I wonder how well George Lucas knew this novel.

“It was around the hub of the evening on the planet of Porlumma when Captain Pausert, commercial traveler from the Republic of Nikkeldepain, met the first of the witches of Karres.”

The library in my hometown of Grande Prairie had two floors. The main floor housed the grown-up books and the lower floor was the kids’ section. The librarian took her job very seriously. She would not let you take books from the shelves on the main floor until she judged you were old enough. I know this for a fact because I tried. I wanted to read those grown-up books so badly. I wanted to know what was in them that I wasn’t supposed to read.

I forget what book it was I brought to her counter from the adult section, but she asked me how old I was and then told me to go put it back. She had a deep, loud voice, unusual for a librarian. Her words carried through the library. Defeated, I put the book back and descended once more to the floor for children.

Then one day I found this book. The Witches of Karres, by James Schmitz. I think now that it had been relegated to the kids’ section by mistake. Not that it was particularly adult in theme or content, but it wasn’t really a book for kids, either. I got it past the librarian without incident, and I read it and kind of liked it, even though I didn’t understand a lot of what was going on in it.

That’s probably the reason the book has stuck with me all these years when so many other books haven’t. Because it was so unlike most of the other books I was allowed to read by our vigilant librarian. I’m not sure but I think Witches was probably the very first science fiction novel I ever encountered. This was before Star Wars. There wasn’t a lot out there for me to compare the book to back then. Interestingly, Witches and Star Wars share some similarities of plot and theme, not to mention a penchant for funny, memorable names for all things alien. Sheewash drive, Yango, the Chaladoor, klatha energy…. I wonder how well George Lucas knew this novel.

Published on November 08, 2012 06:30

November 7, 2012

30 novels, day 7: Fifty words

30 novels, day 7: Green Eggs and Ham

I am Tom.

Tom I am.

I do so love Green Eggs and Ham.

(Okay, technically I suppose one can’t call this a novel, but when I was a child and just learning to read this book seemed gigantic to me. It was an epic adventure. It had mystery, conflict, animals, travel, a plucky, persistent hero, and a startling transformation at the end. And everything rhymed. Magically, wonderfully, ridiculously, everything in the world rhymed. It started with this unnamed … whatever he is … sitting reading in a chair in front a big blue wall. Is he inside? Outside? Hard to tell. Then along comes Sam-I-am, acrobatically standing on the backs of strange creatures, with his signs and his one-track mind about green eggs and ham, and he will not let it go. Sam-I-am is going to pursue this guy to the ends of the earth if that’s what it takes to get him to try green eggs and ham. And just look at how far Sam-I-am and Whatshisname end up going. Look at the stuff that happened to them on the way. The wild ride in the car. The train. The spooky tunnel. The boat. The almighty plunge and crash into the ocean that no one seems to mind, not the people on the train, or the boat, or the animals, everyone is smiling as train and boat and animals hurtle into the water. And Sam-I-am and Whatshisname don’t even notice, they’re still so intent on their mighty contest of wills and words, but at last Whatshisname (did he ever have a name? Did Dr Seuss know what his name was?) gives in and tries the green eggs and ham, which by this time I always thought must be cold and wet and briny from falling into the sea, and yet the guy eats the stuff -- a green egg??? Yuck! -- and likes it. And everyone is happy. And then I had to read it again, to let the spell of the words fall over me one more time. And again and again. And from here I could go on to read bigger books, harder books, books with more than fifty different words, books without rhymes, without pictures, drawn on by the mystery of language and story.)

The fifty words: a, am, and, anywhere, are, be, boat, box, car, could, dark, do, eat, eggs, fox, goat, good, green, ham, here, house, I, if, in, let, like, may, me, mouse, not, on, or, rain, Sam, say, see, so, thank, that, the, them, there, they, train, tree, try, will, with, would, you.

I am Tom.

Tom I am.

I do so love Green Eggs and Ham.

(Okay, technically I suppose one can’t call this a novel, but when I was a child and just learning to read this book seemed gigantic to me. It was an epic adventure. It had mystery, conflict, animals, travel, a plucky, persistent hero, and a startling transformation at the end. And everything rhymed. Magically, wonderfully, ridiculously, everything in the world rhymed. It started with this unnamed … whatever he is … sitting reading in a chair in front a big blue wall. Is he inside? Outside? Hard to tell. Then along comes Sam-I-am, acrobatically standing on the backs of strange creatures, with his signs and his one-track mind about green eggs and ham, and he will not let it go. Sam-I-am is going to pursue this guy to the ends of the earth if that’s what it takes to get him to try green eggs and ham. And just look at how far Sam-I-am and Whatshisname end up going. Look at the stuff that happened to them on the way. The wild ride in the car. The train. The spooky tunnel. The boat. The almighty plunge and crash into the ocean that no one seems to mind, not the people on the train, or the boat, or the animals, everyone is smiling as train and boat and animals hurtle into the water. And Sam-I-am and Whatshisname don’t even notice, they’re still so intent on their mighty contest of wills and words, but at last Whatshisname (did he ever have a name? Did Dr Seuss know what his name was?) gives in and tries the green eggs and ham, which by this time I always thought must be cold and wet and briny from falling into the sea, and yet the guy eats the stuff -- a green egg??? Yuck! -- and likes it. And everyone is happy. And then I had to read it again, to let the spell of the words fall over me one more time. And again and again. And from here I could go on to read bigger books, harder books, books with more than fifty different words, books without rhymes, without pictures, drawn on by the mystery of language and story.)

The fifty words: a, am, and, anywhere, are, be, boat, box, car, could, dark, do, eat, eggs, fox, goat, good, green, ham, here, house, I, if, in, let, like, may, me, mouse, not, on, or, rain, Sam, say, see, so, thank, that, the, them, there, they, train, tree, try, will, with, would, you.

Published on November 07, 2012 05:48

November 6, 2012

30 Novels, day 6: "Who will say a word for my people?"

30 Novels, day 6: Rudy Wiebe’s The Temptations of Big Bear

When I first read this novel in my early twenties, the west that I thought I knew suddenly looked a whole lot bigger. The land itself became more real to me, more alive. The history of my country proved to be darker and more complex than I had imagined or wanted to know. The novel did for me what a great work of literature does: it changed my way of seeing, so that I had no choice but to carry its vision back into the world outside the book.

The novel weaves a multifaceted portrait of the Plains Cree chief whose name translates into English as Big Bear. We see him first through the eyes of white treaty negotiators, who want him to sign a piece of paper he can’t read. A document that will give them ownership over the land, an idea that makes no sense to Big Bear: “No one can choose for only himself a piece of the Mother Earth. She is. And she is for all that live, alike.”

We see the life of Big Bear’s River People as it was on the eve of its vanishing: a rich, vibrant life that dwindles and comes apart as its absolute lifesource, the buffalo, vanishes from the plains and steel rails slice across the earth. In exchange for signing away his people’s freedom to live as they have for millennia, Big Bear’s people will be given food and a small parcel of land to call their own. This is the temptation, and the impossible choice, of Big Bear. His people are hungry. Their way of life is vanishing. Yet saving them means ending that way of life forever.

Wiebe draws attention to the fact that this is not the story of Big Bear but rather one possible recreation of history. He does this through multiple narratives and textual sources, so that the ground always shifts beneath the reader, and history is seen as a gathering (or better a struggle) of viewpoints that no one stands outside of. And yet there’s one omission in this struggle of voices: Wiebe never has Big Bear narrate his own story. He won’t put words in his mouth. He won’t make Big Bear “sign” yet another piece of paper he cannot read.

Illustration: Big Bear at Fort Pitt, Saskatchewan, 1884

When I first read this novel in my early twenties, the west that I thought I knew suddenly looked a whole lot bigger. The land itself became more real to me, more alive. The history of my country proved to be darker and more complex than I had imagined or wanted to know. The novel did for me what a great work of literature does: it changed my way of seeing, so that I had no choice but to carry its vision back into the world outside the book.

The novel weaves a multifaceted portrait of the Plains Cree chief whose name translates into English as Big Bear. We see him first through the eyes of white treaty negotiators, who want him to sign a piece of paper he can’t read. A document that will give them ownership over the land, an idea that makes no sense to Big Bear: “No one can choose for only himself a piece of the Mother Earth. She is. And she is for all that live, alike.”

We see the life of Big Bear’s River People as it was on the eve of its vanishing: a rich, vibrant life that dwindles and comes apart as its absolute lifesource, the buffalo, vanishes from the plains and steel rails slice across the earth. In exchange for signing away his people’s freedom to live as they have for millennia, Big Bear’s people will be given food and a small parcel of land to call their own. This is the temptation, and the impossible choice, of Big Bear. His people are hungry. Their way of life is vanishing. Yet saving them means ending that way of life forever.

Wiebe draws attention to the fact that this is not the story of Big Bear but rather one possible recreation of history. He does this through multiple narratives and textual sources, so that the ground always shifts beneath the reader, and history is seen as a gathering (or better a struggle) of viewpoints that no one stands outside of. And yet there’s one omission in this struggle of voices: Wiebe never has Big Bear narrate his own story. He won’t put words in his mouth. He won’t make Big Bear “sign” yet another piece of paper he cannot read.

Illustration: Big Bear at Fort Pitt, Saskatchewan, 1884

Published on November 06, 2012 07:25