Thomas Wharton's Blog, page 7

November 25, 2012

30 novels, day 25: The latest innovation in reading

30 Novels, day 25: The latest innovation in reading

Yesterday's post about Michael Ende's Momo reminded me that sometimes one needs to take a little time off. So today, instead of a review, I offer this brief excerpt from my book about books, The Logogrpyh:

For those readers with no time for relaxed, contemplative involvement in fiction, this novel offers a delightful alternative. The substance of its original nine-hundred page bulk has been judiciously plucked, abridged, pulverized, filtered, dried and reconstituted; then this concentrated version is repackaged in a contemporary and easily accessible form. And yet, despite what you fear at first, this is still the finest quality literature, straightforwardly thematic, engaging, innovative, devoid of the extravagances of authorial self-indulgence, and savouring of a keen insight into the human condition. Poignant, riveting, and unobtrusive enough that it can be enjoyed while watching television, working at the computer, talking on the cell-phone in rush-hour traffic. And perhaps best of all, no unpleasant afterimages or ethical dilemmas linger past the reading to trouble the rest of your day. This is, in short, the latest innovation in the technology of effortlessness: a novel that allows you to not read.

Published on November 25, 2012 07:12

November 24, 2012

30 Novels, day 24: "Time is life itself, and life resides in the human heart."

30 Novels day 24: Momo, by Michael Ende

Every novel has its own time. Or it is its own time.

There are a few novels that I keep coming back to, over and over again. Each time I read one of these books, I return to not only to its story, but to its time as well. The same events that were happening the last time I read the novel start happening all over again. I may have changed in the intervening years, and my understanding of the book may have changed, but the events of the novel unfold as they did before.

A lot of time can go by in a novel – hours, days, even years – but when I leave the book and return to my own world, I usually find, sometimes to my surprise, that only a short time has passed.

(I’ve wondered if the opposite might happen: that one day I might spend only a few brief moments or hours with a book and then leave it to discover that in my own reality years have gone by.)

Michael Ende is better known for The Neverending Story, a wonderful book in its own right. But in many ways I prefer his earlier, shorter novel Momo. It describes what happens to us, to the world, when we think of time as a commodity, a resource, a possession (as we think of just about everything else). We believe time is something we have a certain amount of, and that if we’re not careful with it our time can be taken away from us by others. We act as if time is something we can save, like money in a bank. In fact we do bank it, for example when we save up sick time or vacation time from work and then “spend” it later.

In the novel, Momo the homeless child discovers that the sinister men in grey are stealing time from the people of her city. They do this by promoting the idea of Timesaving among the populace. People start to deposit their time with the men in grey, and soon all anyone can think about is saving more time. They start giving up on all activities that have come to seem like a waste of time: like play, art, friendship, even sleep. Soon they are stressed out, miserable, but still obsessed with saving time. Sound familiar?

It’s up to Momo to find a way to stop the grey men. She alone understands that by thinking of time in this way, we don’t save anything, in fact we lose something precious.

As David Loy and Linda Goodhew write in their insightful study of modern fantasy The Dharma of Dragons and Daemons, the people of Momo’s city try to “save something that cannot be saved because time is not something we can ever have. We can only be it.”

Or as the narrator of Momo says, “Time is life itself, and life resides in the human heart.”

Every novel has its own time. Or it is its own time.

There are a few novels that I keep coming back to, over and over again. Each time I read one of these books, I return to not only to its story, but to its time as well. The same events that were happening the last time I read the novel start happening all over again. I may have changed in the intervening years, and my understanding of the book may have changed, but the events of the novel unfold as they did before.

A lot of time can go by in a novel – hours, days, even years – but when I leave the book and return to my own world, I usually find, sometimes to my surprise, that only a short time has passed.

(I’ve wondered if the opposite might happen: that one day I might spend only a few brief moments or hours with a book and then leave it to discover that in my own reality years have gone by.)

Michael Ende is better known for The Neverending Story, a wonderful book in its own right. But in many ways I prefer his earlier, shorter novel Momo. It describes what happens to us, to the world, when we think of time as a commodity, a resource, a possession (as we think of just about everything else). We believe time is something we have a certain amount of, and that if we’re not careful with it our time can be taken away from us by others. We act as if time is something we can save, like money in a bank. In fact we do bank it, for example when we save up sick time or vacation time from work and then “spend” it later.

In the novel, Momo the homeless child discovers that the sinister men in grey are stealing time from the people of her city. They do this by promoting the idea of Timesaving among the populace. People start to deposit their time with the men in grey, and soon all anyone can think about is saving more time. They start giving up on all activities that have come to seem like a waste of time: like play, art, friendship, even sleep. Soon they are stressed out, miserable, but still obsessed with saving time. Sound familiar?

It’s up to Momo to find a way to stop the grey men. She alone understands that by thinking of time in this way, we don’t save anything, in fact we lose something precious.

As David Loy and Linda Goodhew write in their insightful study of modern fantasy The Dharma of Dragons and Daemons, the people of Momo’s city try to “save something that cannot be saved because time is not something we can ever have. We can only be it.”

Or as the narrator of Momo says, “Time is life itself, and life resides in the human heart.”

Published on November 24, 2012 07:58

November 23, 2012

30 Novels, day 23: "You have great power inborn in you."

30 Novels, day 23: A Wizard of Earthsea

A boy who discovers he has the power to become a great wizard. His journey to a remote school for wizards, and his difficult life there. A deadly foe who rises as a result of the boy’s power, scars him, and later causes the death of the boy’s mentor, the head wizard. The boy’s quest to set things right, leading to a final battle, and beyond.

Ursula Le Guin’s novel had a seriousness and grandeur I had not encountered before in the fantasy novels I’d been reading as a kid. To me it still stands as one of the few examples of a fantasy novel for children that transcends the trappings of its genre. It doesn’t pander to its audience. It doesn’t lurch awkwardly from comedy to horror and back. It isn’t mawkish or crammed with a cavalcade of contrived and unlikely plot developments. It doesn't retell the same old story that evil is something "out there" and that all problems can be solved with violence.

I think that of all of Le Guin’s Earthsea inventions, I was and remain the most intrigued by the Immanent Grove, the wood near the centre of Roke Island: “It is said that no spells are worked there, and yet the place itself is an enchantment. Sometimes the trees of that Grove are seen, and sometimes they are not seen, and they are not always in the same place and part of Roke Island.” The Grove is the heart of all magic in Earthsea, and Le Guin returns to it again and again in her stories, developing it meanings and the themes of her work through it.

On one level the grove represents the source of a wizard’s magic (the source, not the use, which can be helpful or harmful), and magic in Le Guin’s world represents something about our own world, though Le Guin is wise not to tell us exactly what that is, but instead to let her metaphors unfold and take on larger meaning throughout the series. For me, the Earthsea books evoke something that I find (or search for) only in books of ancient wisdom like the Tao te ching, or the writings of the Zen master Dogen. Books that ask us to go deeper than all the noise and clutter we fill our heads with. To spend some time in the immanent grove within ourselves.

A Wizard of Earthsea was first published in 1968. Its wisdom is more timely now than ever.

Published on November 23, 2012 07:50

November 22, 2012

30 Novels, day 22: Dreams of mountains and snow

30 Novels, day 22: Tintin in Tibet

The adventures of Tintin were the first “graphic novels” I ever encountered. I loved American comic books, too, but you could zip zap pow your way through them in a few minutes, while the Tintin comics were actual books. They were not superhero stories, but they were epic in other ways -- in time and distance, for example.

They were also full of hair-raising action (Tintin had no superpowers and so his death-defying climbs and leaps were all the more exciting), they were full of movement (Tintin’s almost always in motion), they were intriguing mystery stories, and they were very funny.

Tintin in Tibet was my favourite of the stories, and to this day I’m not sure why. Maybe even then, before my family had moved to Jasper, I was already falling under the spell of mountains. And Hergé (whoever he was) could draw wonderful mountains. Actually it seemed he could draw anything and make it look real, and yet somehow better than real.

The simplicity, precision, and clarity of his style appealed to me immensely. Years later I was drawn to the work of Italo Calvino probably because it seemed a written equivalent of the luminous, clutter-free panels of a Tintin book.

I returned again and again to the images of those mountains. Dream-like, infinite, weightless. (This for me is one reason why the recent Tintin movie was a disappointment: it didn’t have that quality of lightness Hergé’s style could give to even the heaviest, most solid things. Even the movie’s Captain Haddock was too “heavy”).

And all that snow. The silent blank snow of the white page beneath the drawings. The story goes that Hergé went to see a psychoanalyst (a student of Jung's) in the late fifties because he was having terrible nightmares in which everything was white. The psychoanalyst advised the artist to stop drawing comic books. Instead, Hergé started work on Tintin in Tibet.

Published on November 22, 2012 06:49

November 21, 2012

30 Novels, day 21: "The inadequacy of truth."

30 Novels, day 21: “The inadequacy of truth”

Discovering the work of Robert Kroetsch was, for me, the discovery that the place I lived, the world I knew, could be written about. Not every novel had to be set somewhere else. This place -- the prairies, mountains, and parkland of Alberta -- was some other place’s somewhere else. It could be exotic, too. Even if you lived here. It could be just as strange and ridiculous and terrifying and heartbreaking as any part of the world.

This place could be story, too.

For a long time Badlandswas my favourite of Kroetsch’s novels. For me it was an easier story to get into, and follow. There was a quest, and a struggle with the elements, and a history I was familiar with. In contrast, I wasn’t sure what Kroetsch was doing in What the Crow Said. It was referred to as a work of Postmodernism, a label that always brought a chill to my reading heart.

Finally I listened to the book. To what the crow was saying. I heard the family resemblance between Kroetsch’s Crowand the tall tales my own grandfather was known for telling and that my own father passed down to me. Once I heard that voice in the book, the voice of the tale-teller, the joker, the prairie bullshitter, I could relax and enjoy the story. I could talk to the book, and it would talk back to me, in a language I knew.

In this novel Kroetsch made Alberta into a tall tale, and it’s still being told, by all of us, every day. Sometimes the truth, the bare facts, really are inadequate, and you have to make up a story, the wilder the better.

Here’s a poem I wrote after Bob died last year on the first day of summer:

Perennial

(in memory of Robert Kroetsch)

A wayward stock escaped from gardens.

Rare along roadsides, fence lines, hazarding the margins of sloughs

or where seedhas been scattered for the wintering birds.

North of here, possibly.Or west.

Late in the seasonbright red berries succeed the white flowers.

When out looking watch for horsetail, prairie sage, cocklebur.

Pull off to the shoulder. Follow the bees.

Enter the church of the grass.

The longest day of summer is the first. Sunset isn’t for hours.

The scent of clover.

Published on November 21, 2012 06:28

November 20, 2012

30 Novels, day 20: Traveling light

30 novels, day 20: Invisible Cities, by Italo Calvino

I’ve carried a copy of this book with me on almost every trip I’ve taken as a writer. Why? Several reasons. First of all, when I go on trips I always like to have a book with me that I’ve already read and know well. I like to visit new places but I’m not good at the actual traveling part, especially when I travel alone. I get anxious in airports and homesick in hotel rooms. Having a familiar, loved book with me helps keep me connected with the world I’ve left behind. And this is a slim book -- easy to carry. Before the invention of the e-book reader, on which I can stow hundreds of novels that weigh nothing at all, I had to be careful how much reading material I brought with me.

But why this slim little volume in particular? In the novel, Marco Polo has traveled all the way to China from Venice to meet the emperor, Kublai Khan. If Polo was able to make those epic journeys, most on foot (or by horse or camel) I figure I should be able to survive the rigors of modern air travel.

In Calvino’s novel (if it is a novel), the young Venetian describes for the great Khan the wondrous cities he’s visited in his travels. Most of the book consists of these brief, poetic, fantastical descriptions of impossible cities. It was thanks to this book that I conceived the idea of writing a collection of descriptions of imaginary, impossible books, which eventually became my short fiction collection The Logogryph.

And, lastly, I take Calvino’s book with me on my journeys as a writer because, for me, Calvino is the consummate writer: his inventiveness, his ability to transform the mundane and familiar into the wondrous and strange, is an ideal I strive for in my own work. Having some Calvino with me on a journey reminds me to pay attention and keep my mind open to whatever comes.

I brought a copy of Invisible Cities with me when I went to China in 2002 as a member of a delegation of Canadian writers. The guide assigned to look after us during our stay, the gracious, unflappable, and ever-punctual Mr Niu, had never heard of Calvino or this book (set in a fairy-tale version of his own country).

When we were at the Ningbo airport, about to head home for Canada, I thought I should give Mr Niu a parting gift, but it was too late to buy anything. Then I remembered he was a writer of travel essays as well as a guide. I gave him my copy of Invisible Cities.

Published on November 20, 2012 09:34

November 19, 2012

30 Novels, day 19: Samuel R Delany's Dhalgren

30 Novels, day 19: "I suspect the whole thing is science fiction."

Dhalgren, by Samuel R Delany

I had a habit in my early teens of seeking out and reading books I probably shouldn’t have been reading, books I wasn't old enough for. Which is another way of saying I encountered these books at just the right time. Few things are more likely to turn a reader into a writer than the wrong book.

Samuel R Delany’s Dhalgren was one of these books. It was supposed to be science fiction, the Bantam paperback cover made it look like science fiction, and so I was expecting science-fictiony things to happen in it. But the stuff that happened in this book was like nothing in any of the science fiction I’d ever read up to that point.

In the first few pages, a woman turns into a tree. And then a lot of other bizarre, inexplicable, unexplained things happen. The nameless Kid who’s the hero (is he?) of the book enters the “restricted” city of Bellona, where some kind of vague catastrophe has occurred, and society has collapsed. He hooks up with this gang of young people who go around covered in these holographic “light shields” shaped like animals. One day a red, swollen sun appears in the sky, apocalyptic and terrifying, and then after it sets, life goes on as before (a prescient image of our current inertia in the face of global warming?).

A lot of very real things happen in this book, too: people eat, and talk, and fight, and make love. A boy falls into an empty elevator shaft and dies and his family grieves. The sexual explicitness of the book was an education all in itself. And everything, the fantastical and the mundane, is rendered in the same vivid, meticulous, stream-of-consciousness-laced prose (which probably helped me to read Joyce when I finally got around to him).

Something else I noticed for the first time when I read this book: the words it was made of. The author’s way of describing things was unusual. His verbs were strange, active, alive. Even inanimate things seemed to have life and will in his sentences:

The asphalt spilled him onto the highway’s shoulder. The paving’s chipped edges filed visions off his eyes…. He looked in the lightening sky for shapes. Mist bellied and folded and coiled and never broke.

I hadn’t paid much attention to style before as a reader. This book forced it into my consciousness, made me aware of the fact that there was more going on here than just a story. There was the weave of language itself, the shaping of it. I began to think that I would like to do that, too. Do things with words. This is how a reader becomes a writer.

Dhalgren, by Samuel R Delany

I had a habit in my early teens of seeking out and reading books I probably shouldn’t have been reading, books I wasn't old enough for. Which is another way of saying I encountered these books at just the right time. Few things are more likely to turn a reader into a writer than the wrong book.

Samuel R Delany’s Dhalgren was one of these books. It was supposed to be science fiction, the Bantam paperback cover made it look like science fiction, and so I was expecting science-fictiony things to happen in it. But the stuff that happened in this book was like nothing in any of the science fiction I’d ever read up to that point.

In the first few pages, a woman turns into a tree. And then a lot of other bizarre, inexplicable, unexplained things happen. The nameless Kid who’s the hero (is he?) of the book enters the “restricted” city of Bellona, where some kind of vague catastrophe has occurred, and society has collapsed. He hooks up with this gang of young people who go around covered in these holographic “light shields” shaped like animals. One day a red, swollen sun appears in the sky, apocalyptic and terrifying, and then after it sets, life goes on as before (a prescient image of our current inertia in the face of global warming?).

A lot of very real things happen in this book, too: people eat, and talk, and fight, and make love. A boy falls into an empty elevator shaft and dies and his family grieves. The sexual explicitness of the book was an education all in itself. And everything, the fantastical and the mundane, is rendered in the same vivid, meticulous, stream-of-consciousness-laced prose (which probably helped me to read Joyce when I finally got around to him).

Something else I noticed for the first time when I read this book: the words it was made of. The author’s way of describing things was unusual. His verbs were strange, active, alive. Even inanimate things seemed to have life and will in his sentences:

The asphalt spilled him onto the highway’s shoulder. The paving’s chipped edges filed visions off his eyes…. He looked in the lightening sky for shapes. Mist bellied and folded and coiled and never broke.

I hadn’t paid much attention to style before as a reader. This book forced it into my consciousness, made me aware of the fact that there was more going on here than just a story. There was the weave of language itself, the shaping of it. I began to think that I would like to do that, too. Do things with words. This is how a reader becomes a writer.

Published on November 19, 2012 07:29

November 18, 2012

30 Novels, day 18: A Life-long Adventure

30 Novels, day 18: A Life-Long Adventure

Guest post by Bill Thompson

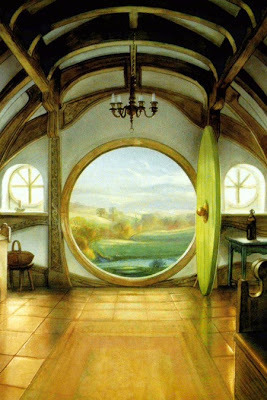

As a kid, I was never much of a reader. I looked at my dad’s newspapers, the covers of my mom’s novels, and I flipped through the pictures in the National Geographic. In grade five, we had a series in our class that was supposed to help with reading comprehension. I was put in the orange readers, halfway between the books for dummies and those for the average kids in the class.The summer after grade five I was blinded in a car accident. I spent four months in hospital because of a badly broken leg. My world had changed. Apart from trying to adjust to being blind after eleven years of running, biking, and rough-housing, the unspeakable boredom of the hospital bed nearly drove me crazy.One day two women from the school board came to visit me. They brought me an oversized, open-reel tape recorder and some recorded books. One of those books was J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit.The world of The Hobbit was the world as I had never imagined it. I had thought elves were diminutive shoemakers, while dwarfs were funny little characters with funnier names who helped runaway princesses.In Tolkien’s world, the dwarves--not dwarfs--still had funny names, but they went on quests to steal back dragon-guarded treasure, while elves were tall, beautiful, and a little threatening. And what was a hobbit?After the traction came off my leg, they put me in a body cast: three months flat on my back, and I was finally able to get up. One night after the nurses had done their rounds, I maneuvered myself out of bed, and hobbled and cruched my way down the hall to the schoolroom, the room for all the kids who were too damaged or messed up to go into the regular hospital classroom. In that room, at the root of a mountain, the strangest creature I had ever met waited for me; for me and a little hobbit, who was lost, in the dark, and all alone.Meeting Bilbo, Gollum, and Smaug introduced me to a world of books that became my lifeline and my world. It took the place of the life I had lost, and it gave the visual center of my brain something to do. I imagined myself into every book I read, sometimes scaring myself into nights of wakefulness, as I did with H. G. Wells The Time Machine and later Bram Stoker’s Dracula. I have been on that road ever since, and it all began at a round, green door with a pipe-smoking hobbit named Bilbo Baggins, and an unexpected adventure to lands faraway.

Bill Thompson is an Edmonton writer and teacher of English.

Published on November 18, 2012 07:33

November 17, 2012

30 novels, day 17: The briefest review to be posted on this blog yet

Published on November 17, 2012 06:23

November 16, 2012

30 Novels, day 16: Where the rivers begin

30 Novels, day 16: Icefields by Thomas Wharton

It occurred to me that if I’m going to devote this blog all November to the novels that shaped me as a writer, I shouldn’t forget this book.

This was my own first novel, and it was important to me as a writer because, by writing it, I proved to myself that I actually could write a novel.

As I mentioned in my earlier post on Sheila Watson’s The Double Hook, I had a difficult time figuring out how to write a novel, let alone figuring out what to write about. Creating an outline and working through it in linear fashion didn’t work for me at all. I had to discover my own method of putting a novel together. It was a messy, trial-and-error method, with a lot of dead ends and blind alleys.

Sharon and I were living in the small northern Alberta town of Peace River at the time I was writing this book. Sharon was working at the hospital and I was an unemployed at-home Dad, looking after our baby daughter and trying to finish my Master’s degree (my thesis was the novel). From my little upstairs office in our house I had a view of the local ski hill across the river, known as Misery Mountain. It seemed an aptly-named landmark to write a novel in front of.

The book is set in Jasper, Alberta, the mountain resort town that I lived in as a teenager. I was already a big reader in those days, and my favourite reading was fantasy. The forested hills and valleys around the townsite became a canvas on which I could imagine the fantastical worlds I loved to read about, like Tolkien’s Middle Earth.

It was in Jasper that I began to imagine I might write my own fantasy novels some day. I didn’t think at the time that I would ever write about Jasper itself, the actual town and wilderness around it. But when I was working on the short fictions that eventually became my first novel, that’s what began to emerge: stories about bears, mountaineers, explorers. And glaciers.

The fantasy novels had to wait until years later.

It occurred to me that if I’m going to devote this blog all November to the novels that shaped me as a writer, I shouldn’t forget this book.

This was my own first novel, and it was important to me as a writer because, by writing it, I proved to myself that I actually could write a novel.

As I mentioned in my earlier post on Sheila Watson’s The Double Hook, I had a difficult time figuring out how to write a novel, let alone figuring out what to write about. Creating an outline and working through it in linear fashion didn’t work for me at all. I had to discover my own method of putting a novel together. It was a messy, trial-and-error method, with a lot of dead ends and blind alleys.

Sharon and I were living in the small northern Alberta town of Peace River at the time I was writing this book. Sharon was working at the hospital and I was an unemployed at-home Dad, looking after our baby daughter and trying to finish my Master’s degree (my thesis was the novel). From my little upstairs office in our house I had a view of the local ski hill across the river, known as Misery Mountain. It seemed an aptly-named landmark to write a novel in front of.

The book is set in Jasper, Alberta, the mountain resort town that I lived in as a teenager. I was already a big reader in those days, and my favourite reading was fantasy. The forested hills and valleys around the townsite became a canvas on which I could imagine the fantastical worlds I loved to read about, like Tolkien’s Middle Earth.

It was in Jasper that I began to imagine I might write my own fantasy novels some day. I didn’t think at the time that I would ever write about Jasper itself, the actual town and wilderness around it. But when I was working on the short fictions that eventually became my first novel, that’s what began to emerge: stories about bears, mountaineers, explorers. And glaciers.

The fantasy novels had to wait until years later.

Published on November 16, 2012 07:50