Thomas Wharton's Blog, page 10

October 15, 2012

Rat Hole

We used to feel that nothing ever happened in this town. Every winter it seemed time itself had frozen along with everything else.

From a safe vantage point on the outskirts you could watch people drive into our city and to your eyes they

would appear to have

utterly stopped

moving.

We all secretly knew why things were like this. It was because of the singularity at the heart of our town. The tunnel we called, with our usual self-mockery, the rat hole.

It ran under a railroad crossing at the edge of downtown. It was only an intersection long. But the rat hole was more than just a tunnel, and we all knew it. Eventually, no matter where your business took you, you’d find yourself having to pass through the rat hole to get from one side of the city to the other. And even if you didn’t have to take that route, often you did so anyway, as if the rat hole’s gravity compelled you, like a coin circling a drain, down into its grimy, graffiti-adorned, ill-lit cloaca.

Cars went through the hole, switching on their headlights and narrowly missing each other as they exchanged photons, then came out the other side. It took what … maybe ten seconds to traverse? No big deal, right. And yet every time we passed through the rat hole we knew something had changed.

Coming back out into the daylight, you always felt a moment of doubt about just where you were. As if maybe you'd passed through into an alternate reality. For a moment this utilitarian city seemed exotic. Alien. Even interesting.

In our odd, contradictory way we loved our rat hole. It was an ancient deep space object, for sure, an artifact from the founding of the city or the universe, that made us feel how far-flung we were out here on the prairie from newer, better cities, with soaring overpasses, freeways with multiple lanes, improved, scientifically-planned traffic flow.

Yes, it had to go. We admitted that. We even looked forward to it. The rat hole was a hazard, an eyesore, an embarrassment. So we got rid of it. A couple of weeks, or more likely months, of construction, and it was gone. We thought we didn’t miss it. We liked being able to zip from one side of downtown to the other without that nerve-jarring plunge into rushing glare and gloom.

A lot happens in this town these days. Just like you we’re busy busy busy here. We’re becoming important. There are soaring overpasses, freeways with multiple lanes, improved scientifically-planned traffic flow (okay, that one never really worked out, but apparently it doesn’t anywhere else, either). Now we’re a lot like every other big city. Our patch of the universe emits the same uniform background hum as everyone else's.

We miss our rat hole, though. We do. But who knows what might happen in our future. It may well be that as our city grows too large for itself, its core will collapse under its own density and importance. And then one day we’ll be driving along and we’ll discover there’s a brand new gravity well in our midst that’s tugging us into it. A new rat hole that will fling us through the dark to the far side of ourselves.

From a safe vantage point on the outskirts you could watch people drive into our city and to your eyes they

would appear to have

utterly stopped

moving.

We all secretly knew why things were like this. It was because of the singularity at the heart of our town. The tunnel we called, with our usual self-mockery, the rat hole.

It ran under a railroad crossing at the edge of downtown. It was only an intersection long. But the rat hole was more than just a tunnel, and we all knew it. Eventually, no matter where your business took you, you’d find yourself having to pass through the rat hole to get from one side of the city to the other. And even if you didn’t have to take that route, often you did so anyway, as if the rat hole’s gravity compelled you, like a coin circling a drain, down into its grimy, graffiti-adorned, ill-lit cloaca.

Cars went through the hole, switching on their headlights and narrowly missing each other as they exchanged photons, then came out the other side. It took what … maybe ten seconds to traverse? No big deal, right. And yet every time we passed through the rat hole we knew something had changed.

Coming back out into the daylight, you always felt a moment of doubt about just where you were. As if maybe you'd passed through into an alternate reality. For a moment this utilitarian city seemed exotic. Alien. Even interesting.

In our odd, contradictory way we loved our rat hole. It was an ancient deep space object, for sure, an artifact from the founding of the city or the universe, that made us feel how far-flung we were out here on the prairie from newer, better cities, with soaring overpasses, freeways with multiple lanes, improved, scientifically-planned traffic flow.

Yes, it had to go. We admitted that. We even looked forward to it. The rat hole was a hazard, an eyesore, an embarrassment. So we got rid of it. A couple of weeks, or more likely months, of construction, and it was gone. We thought we didn’t miss it. We liked being able to zip from one side of downtown to the other without that nerve-jarring plunge into rushing glare and gloom.

A lot happens in this town these days. Just like you we’re busy busy busy here. We’re becoming important. There are soaring overpasses, freeways with multiple lanes, improved scientifically-planned traffic flow (okay, that one never really worked out, but apparently it doesn’t anywhere else, either). Now we’re a lot like every other big city. Our patch of the universe emits the same uniform background hum as everyone else's.

We miss our rat hole, though. We do. But who knows what might happen in our future. It may well be that as our city grows too large for itself, its core will collapse under its own density and importance. And then one day we’ll be driving along and we’ll discover there’s a brand new gravity well in our midst that’s tugging us into it. A new rat hole that will fling us through the dark to the far side of ourselves.

Published on October 15, 2012 10:01

October 11, 2012

Suddenly

Suddenly, without warning, the Guild of Storymakers realized they’d been using too much Suddenly in their work. By some oversight in the paperwork they’d far exceeded the normal quota of Suddenly. The stuff was everywhere now, and it would have to be cleaned up and rooted out before it caused an overload and stories began to collapse. But how to get rid of it? Suddenly the doors of the Guild’s secret meeting chamber flew open and in strode Eric the Hedgehog Prince. He was a tall and muscular young man with a hedgehog’s snout and a great mane of quills. “How dare you?” the Guild president shrieked. No storyfolk were ever allowed in the meeting chamber because it was the place where all the decisions about their lives were made, which meant that what went on there was none of their business. “I dare because I have no choice,” the Prince declared. “My life, and the lives of everyone I know, have become plagued by unexpected, unlikely, perilous, abrupt and instantaneous occurrences. More than usual, I mean, and I demand to know what you’re going to do about it.” The Guild members looked at one another sheepishly. They had just been discussing that very question and no one had any answers. Suddenly the guildmember in charge of Complications burst in. “I just received this letter by Gryphon Post,” she announced. “The Minotaurs of the Labyrinthine Desert have declared war on us. They say they’ve become plagued by unexpected, unlikely, perilous, abrupt and instantaneous occurrences, and they have no recourse but to take vengeance on us and destroy our Guild.” “Wouldn’t you know it,” muttered the president. “What are we going to do?” “There’s a postscript to the letter,” said the guildmember in charge of Complications. “It states that in order to avoid messy carnage, their champion is willing to meet a champion of ours in single combat to decide the issue.” “We don’t have a champion,” moaned the Secretary of Dire Circumstance. “All the champions of Story are up to their necks in unexpected, unlikely, perilous, abrupt and instantaneous occurrences.” “I will be your champion,” Eric the Hedgehog Prince declared. And he strode forth from the chamber and through the Guild halls and out across the Plain of Plot Advancement, until he came to the hill of Rising Action and climbed to its top. From there he could see the Minotaur Army spread out upon the plain, their spears and armour glinting in the sun, and suddenly he knew fear. Then, just as suddenly, from among the assembled multitude came a Minotaur who was taller than all the rest. One of the very rare Minotaur Giants she was, from the Isle of Combinatory Tropes, and she was the Queen of all Minotaurs. The Hedghog Prince drew his great bow of yesterwood, and plucked one of his own mighty quills from his back and fitted it to the bowstring. Yet he saw that the Minotaur carried no weapon, and her eyes were gentle and sad. And she was smoking hot, as well. Suddenly she was there in front of him. “Noble prince,” she said, in a voice like a softly bubbling pool of lava. “I have marched my people here not with any intent of war, but only to find a solution to this problem. It occurred to me that if I marshaled a huge force and brought them across many miles of Story, we would probably encounter quite a lot of Suddenly along the way. And so it has proved. We’ve run into many unexpected, unlikely, perilous, abrupt and instantaneous occurrences on our journey, and used them up.” Suddenly the Hedgehog Prince was smitten with love for the Minotaur Queen, and it was a hopeless love, for he knew she could never return his feelings. How could she ever love someone with the face of a small nocturnal mammal? “You are very wise, Your Majesty,” he said with a bow. “But a great deal of Suddenly still remains.” “We will ask the Guild to issue an immediate ban on the use of Suddenly,” the Queen said. “No Suddenly will be allowed in any story. There will be a moratorium on it, until such time as our world recovers.” She held out her large but slender and graceful hand. “I ask you, Prince,” she went on, “in the spirit of friendship, to join me in hunting and tracking down Suddenly wherever we find it.” The Prince took the Minotaur Queen’s hand, and with an aching heart he vowed to join her in her quest, and all the Minotaurs cheered. Meanwhile, in another part of the Realm of Story, the Society of Rival Storycrafters was meeting to decide what to do about the sudden and disastrous proliferation of Meanwhiles.

Published on October 11, 2012 08:00

October 5, 2012

City of Readers

A story (slightly edited for this blog) from my collection The Logogryph, about a utopian city of readers. I’m not sure, but it might be Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan.

The city is surrounded by a wall two thousand paces in circumference, and by an encircling moat as well. The houses of the citizens are roomy and comfortably adorned, solid and strong in construction. Everywhere there are wide doorways and broad courts, with benches and shade trees. The houses all have tall windows of fine glass let in the light from all sides.

The streets themselves are made of the hardest flagstones, which are frequently replaced, as the nightly pacing of the city’s numberless insomniacs and sleepwalkers swiftly wears them out.

The grand temple, dedicated to those few citizens who have attained transfiguration, is both imposing and splendid, built of ornately carved stone, full of lit candles, and admirable for its polished and immaculate shelving. The numerous relics of the Transfigured are laid out with simple dignity in alcoves: most moving are the pairs of bent and tarnished wire spectacles, which give silent testimony to many diligent hours.

Adjacent to this temple is an enclosed hermitage, in which literary agents, publishers and other sinners are received as penitents. If any of them, however, is found to have relapsed into their former vices they are weighted with broken inkstones and thrown into the moat. Thus these functionaries learn to adopt a modest and a holy life; evil rumour is rarely heard of them.

There is also a university in this city, but scarcely a book is to be seen in its halls and residences, and indeed the students make a great show of their own ignorance and laziness, so much so that young people have flocked from far and wide, upon report of the great orgies of time-wasting to be enjoyed here. And it would seem that the parents and older citizens not only tolerate but encourage such behavior, for, as was explained to me, how else will the young acquire the discipline needed to idle away the rest of their lives with books?

It is believed that within the city there are at present over five hundred optometrists and sixty thousand librarians. Eighteen of these latter, usually the most capricious and heterodox, are chosen yearly as anti-censors, whose duty it is to ensure that no book is ever banned or prevented from reaching any reader. There is also a body of officials whose function is to ensure that any disturbing or scandalous volumes are distributed at random through the city, in order that the wrong reader may come upon them by accident, and so complicate and deepen her reading life with matter that she may otherwise never have encountered.

You may well ask how such imposing walls and grand houses are constructed in such a city. Whence comes their obvious wealth? The answer is that the people do as much work as is required to maintain life and enjoyment, and as the rest of their time is given over to reading, they squander neither a moment nor a penny on dubious pursuits like gaming, whoring or investing. Surplus funds go into a public trust which is meant to be shared out equally amongst all, although it is true that this ideal is seldom realized: not because those in charge of the funds are avaricious or deceitful, but simply because they are too wrapped up in the latest novel to be diligent with tallies and figures.

Even though many people here print and publish their own books, carts of volumes arrive daily from many lands. From China arrive slim chapbooks of poems and philosophical fragments, the pages woven of fine embroidered silk, or painted in tiny hand on plaques of delicate porcelain. From Italy are brought collections of tales both fabulous and bawdy, the pages of which smell strongly of pepper and cheese. From the northern lands come a great many heroic epics wrapped warmly in the skins of fox, ermine, sable and lynx, or stowed among salted herring. The English ship their famed tragedies and comedies in amongst casks of ale and boxes of silverware. From the new world, by way of Spain, come books of magic spells and fat novels, inked with leopard’s blood and bound in precious stones from the beds of poisonous rivers.

It is also wondrous how much produce is brought into the city day after day. Trains of wagons come in through the gates loaded with eggs, meat and fish. Flour, bread and pastries arrive in tremendous masses; nonetheless, by evening nothing is left in the marketplace to be bought.

It is not the citizens themselves who devour all of this bounty of the earth, however. Instead, they purchase it for the numerous household guests who visit at all times of the year, in order to escape their own clamorous, hectic lives. As anyone who devotes a life to books well knows, tranquil solitude is a kind of vacuum that attracts the noisy and the inquisitive. Rather than struggle against this law of nature, almost every citizen operates, from out of his own house, a tavern for feasting and wine-bibbing. When friends and relations arrive on the doorstep with their luggage, their sunburns, and their sticky children, the inhabitants heat up the stoves, prepare succulent dishes, fetch in musicians and harlots, and let all proceed as it will, while they themselves retire to some sheltered spot, where the enjoyment of a book is perhaps given even greater relish by the adjacent din.

Of course, for such a large and noble city, this means that there is much licentiousness and vandalry. Brawls erupt often between rival mobs of visitors vying for the spoils. Hardly an evening goes by without a skirmish or an ambuscade, and when such clashes occur, there is no one to separate the contending parties. There are no magistrates such as we know them, no officers of the law, no collectors of revenues other than those who collect the tax on wine, which everyone must pay. If outright robbery is committed, or murder, or any other disruption of the civil peace, the ire of the citizenry at having their reading interrupted by the necessities of law and order leads to swift vigilante trial and justice, though most often even the rumour of one of these avenging mobs of disturbed readers is enough to drive an offender from the city in terror.

Truly any city would be better off without such evils, but you will find few here beset with worry about the matter. Books are made of paper and ink, they will remind you, but also of foolishness and immoderation. And so those whose lives are the most plagued by tumult and trouble are those in whom most often you will see the signs of approaching transfiguration: the pallid, almost translucent skin, the soundless step, the fading shadow. On faces lined with long forbearance and great suffering you will find the light in the eyes that comes from another place, from the knowledge that one day soon, their loved ones will awaken to find them gone from their beds, from their sofas and benches and hammocks, and will then, with mingled contentment and eagerness, begin the search for them in the pages of books that they have not yet opened.

The city is surrounded by a wall two thousand paces in circumference, and by an encircling moat as well. The houses of the citizens are roomy and comfortably adorned, solid and strong in construction. Everywhere there are wide doorways and broad courts, with benches and shade trees. The houses all have tall windows of fine glass let in the light from all sides.

The streets themselves are made of the hardest flagstones, which are frequently replaced, as the nightly pacing of the city’s numberless insomniacs and sleepwalkers swiftly wears them out.

The grand temple, dedicated to those few citizens who have attained transfiguration, is both imposing and splendid, built of ornately carved stone, full of lit candles, and admirable for its polished and immaculate shelving. The numerous relics of the Transfigured are laid out with simple dignity in alcoves: most moving are the pairs of bent and tarnished wire spectacles, which give silent testimony to many diligent hours.

Adjacent to this temple is an enclosed hermitage, in which literary agents, publishers and other sinners are received as penitents. If any of them, however, is found to have relapsed into their former vices they are weighted with broken inkstones and thrown into the moat. Thus these functionaries learn to adopt a modest and a holy life; evil rumour is rarely heard of them.

There is also a university in this city, but scarcely a book is to be seen in its halls and residences, and indeed the students make a great show of their own ignorance and laziness, so much so that young people have flocked from far and wide, upon report of the great orgies of time-wasting to be enjoyed here. And it would seem that the parents and older citizens not only tolerate but encourage such behavior, for, as was explained to me, how else will the young acquire the discipline needed to idle away the rest of their lives with books?

It is believed that within the city there are at present over five hundred optometrists and sixty thousand librarians. Eighteen of these latter, usually the most capricious and heterodox, are chosen yearly as anti-censors, whose duty it is to ensure that no book is ever banned or prevented from reaching any reader. There is also a body of officials whose function is to ensure that any disturbing or scandalous volumes are distributed at random through the city, in order that the wrong reader may come upon them by accident, and so complicate and deepen her reading life with matter that she may otherwise never have encountered.

You may well ask how such imposing walls and grand houses are constructed in such a city. Whence comes their obvious wealth? The answer is that the people do as much work as is required to maintain life and enjoyment, and as the rest of their time is given over to reading, they squander neither a moment nor a penny on dubious pursuits like gaming, whoring or investing. Surplus funds go into a public trust which is meant to be shared out equally amongst all, although it is true that this ideal is seldom realized: not because those in charge of the funds are avaricious or deceitful, but simply because they are too wrapped up in the latest novel to be diligent with tallies and figures.

Even though many people here print and publish their own books, carts of volumes arrive daily from many lands. From China arrive slim chapbooks of poems and philosophical fragments, the pages woven of fine embroidered silk, or painted in tiny hand on plaques of delicate porcelain. From Italy are brought collections of tales both fabulous and bawdy, the pages of which smell strongly of pepper and cheese. From the northern lands come a great many heroic epics wrapped warmly in the skins of fox, ermine, sable and lynx, or stowed among salted herring. The English ship their famed tragedies and comedies in amongst casks of ale and boxes of silverware. From the new world, by way of Spain, come books of magic spells and fat novels, inked with leopard’s blood and bound in precious stones from the beds of poisonous rivers.

It is also wondrous how much produce is brought into the city day after day. Trains of wagons come in through the gates loaded with eggs, meat and fish. Flour, bread and pastries arrive in tremendous masses; nonetheless, by evening nothing is left in the marketplace to be bought.

It is not the citizens themselves who devour all of this bounty of the earth, however. Instead, they purchase it for the numerous household guests who visit at all times of the year, in order to escape their own clamorous, hectic lives. As anyone who devotes a life to books well knows, tranquil solitude is a kind of vacuum that attracts the noisy and the inquisitive. Rather than struggle against this law of nature, almost every citizen operates, from out of his own house, a tavern for feasting and wine-bibbing. When friends and relations arrive on the doorstep with their luggage, their sunburns, and their sticky children, the inhabitants heat up the stoves, prepare succulent dishes, fetch in musicians and harlots, and let all proceed as it will, while they themselves retire to some sheltered spot, where the enjoyment of a book is perhaps given even greater relish by the adjacent din.

Of course, for such a large and noble city, this means that there is much licentiousness and vandalry. Brawls erupt often between rival mobs of visitors vying for the spoils. Hardly an evening goes by without a skirmish or an ambuscade, and when such clashes occur, there is no one to separate the contending parties. There are no magistrates such as we know them, no officers of the law, no collectors of revenues other than those who collect the tax on wine, which everyone must pay. If outright robbery is committed, or murder, or any other disruption of the civil peace, the ire of the citizenry at having their reading interrupted by the necessities of law and order leads to swift vigilante trial and justice, though most often even the rumour of one of these avenging mobs of disturbed readers is enough to drive an offender from the city in terror.

Truly any city would be better off without such evils, but you will find few here beset with worry about the matter. Books are made of paper and ink, they will remind you, but also of foolishness and immoderation. And so those whose lives are the most plagued by tumult and trouble are those in whom most often you will see the signs of approaching transfiguration: the pallid, almost translucent skin, the soundless step, the fading shadow. On faces lined with long forbearance and great suffering you will find the light in the eyes that comes from another place, from the knowledge that one day soon, their loved ones will awaken to find them gone from their beds, from their sofas and benches and hammocks, and will then, with mingled contentment and eagerness, begin the search for them in the pages of books that they have not yet opened.

Published on October 05, 2012 07:23

October 2, 2012

Where Do You Get Your Stories From?

The other day someone asked me, “Where do you get your stories from?”

“From everything,” I said. It wasn’t a very helpful answer, but it felt true. For me, a story comes together from so many elements. From memories, from experiences, from a bit of conversation overheard on the bus, from odd thoughts that just pop into my head, seemingly out of nowhere.

And from other stories.

Lined up on my writing desk, within easy reach, is a row of indispensable books. Not all of them are reference works like dictionaries. Some of these books I might not consult very often but I like to know they are there. A few are, for me, the important books of my life as a reader and a writer. One of these books is The Complete Grimm's Fairy Tales.

I bought my first copy (Pantheon, Hunt and Stern translation, illustrations by Josef Scharl), back in the 1970's. Back then, like everyone else, I knew only the famous handful of Grimm: The Frog Prince, Rapunzel, Hansel and Gretel…. So it was a shock to me to flip through this massive book and discover there were hundreds of others stories. Stories I’d never heard of. Stories I couldn’t wait to read (yes, I was a strange kid). The book was $7.95 or so and I remember deliberating over it for half an hour in the bookstore because this was a lot of money to me back then, when my source of income was a paper route. But I had to have it. When I brought the book up to the counter the bookseller smiled and said, “Finally decided, eh?”

That copy of the tales was poured through many, many times and at last, after many years, the book cracked in half. So recently I went out and bought an updated version of the Pantheon edition ($26.95, but now I've got more spending money so it's okay).

Over the years I read these tales to my kids, but they always seemed restless when I did, which was not the case with other, more contemporary books and stories. It occurred to me that the tales come from a slower time, when the storyteller was the sole source of entertainment for people in small towns and villages. My kids have grown up in a faster world, where stories and images are a constant bombardment, often geared to selling something.

But I also discovered that if I read over one of the tales to myself beforehand and memorized its shape, I could tell it to the kids, and that went much more successfully. The point was not to memorize the tale word for word. Just to know it well enough that I could tell it in my own words.

So where do I get my stories from? When I sit down to write, part of me is still a kid, going quiet and listening expectantly because someone is going to tell me a story. Yes, I’m the one writing it, but deep down there’s a feeling that I’m the listener, not the teller. The story grows from all the elements it needs to grow. Sometimes it arrives as a complete surprise. Sometimes it seems like I'm not the one getting the story from anywhere. It comes and gets me. Or we both set out, the story and I, from different places, and eventually meet somewhere on a road. I like it best when that happens. That's why I always write not so much to say something as to have something said to me. The story has come all this way to be here, and I want to hear what it has to tell.

Published on October 02, 2012 06:20

September 24, 2012

The Fable of Brother Buchreder

I had a great time at the Lethbridge Word on the Street Festival and read a new non-fiction piece about fear of bears. A piece so new I was still tinkering with it just before I went up onstage to read.

I also got to see a former student of mine, Matt Schneider, who lives in Lethbridge and is working on his PhD dissertation on the materiality of video games. Matt is also a writer of fiction and he kindly agreed to share a story of his on the Perilous Realm blog, a brief tale that booklovers will enjoy, called The Fable of Brother Buchreder.

Matt has a blog of his own about all things bookish and then some, at buchstauben.com

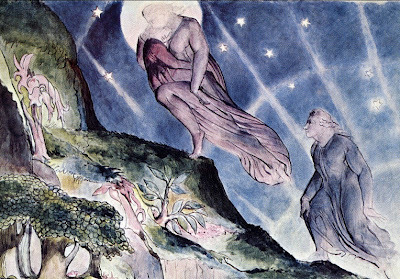

Note: the last line of the story is a quote from Dante's Inferno, which translates roughly into English as "And we came out once more under the stars."

Illustration: "Lucia Carrying Dante" by William Blake

Published on September 24, 2012 07:50

September 21, 2012

The Adventures of Gord Watching Hockey

Tales from the Golden Goose: The Adventures of Gord Watching Hockey

Gord avalanched into his recliner. He grasped the TV remote and jabbed his thumb down on the button of power.

Rapid-fire images of commercial enticement cascaded and danced before his eyes. Gord dragged air in and out of his lungs. His mouth sagged open.

One image at last flung hooks of interest that caught hold of his eyes and tugged. Hockey. The blaring theme song called to his blood.

Gord burrowed into the creaking leather of the chair and watched, watched, watched.

The play ceased. The period break slammed into his absorption like a body check. Gord stirred in his chair. His domelike stomach emitted a deep, gurgling, rhinocerotic growl.

From a rotund bowl on the table at his side Gord captured a rippled chip of potato. His jaws snapped down upon it, his molars grinding, grinding. The heady savour of salt and caustic vinegar smacked his olfactory and gustatory nerve endings upside the head. Swiftly he snatched up another chip and crushed it into paste, then another and another.

With a decisive squeeze he wrenched off the unwilling cap of a cold brown bottle, tilted his head back and sluiced down a foaming, bubbling tide of Alberta-made big-name brand beer, his neck pulsing like a wild thing.

Hockey returned and again Gord watched with all his might, his capacious flesh jerking and rippling to the movements on the screen, grunts and other ejaculations of vicarious team spirit and zeal rising frequently from his throat. Come on!... Damn it!... Aww jeeziz guy!…Oh … oh … oh YEAH!

There were many exciting plays, and more beers cracked open and chugged down to toast them. At the appointed time the game ended, happily as it turned out for the team of Gord’s affections. The late evening news came on. There were a few broken bits of potato chip left in the bowl. Gord plucked them out and ate them, staring glassily at rapid-fire images of unpleasant happenings around the world. Then the sports news came on and Gord relived the night’s most exciting plays and cheered once more at that totally awesome goal.

With his tongue Gord zambonied the remaining crumbs and salt from his lips. A Brobdingnagian belch volcanoed up from the core of his being, followed by a face-cracking, leonine yawn that shook his mighty frame and shuddered down into his toes.

Once again, as he had before, Gord prodded the button of power. The screen went dark.

Silence bombarded the room like an aerial bombardment of very quiet warplanes.

Gord's eyes clanged shut like portcullises. He stampeded his way down into the beery vales of sleep.

Author's note: this piece began as a writing exercise about verbs. I wanted to see if I could make a very passive activity sound active and exciting by using strong, active verbs. I chose the most passive activity I could think of -- sitting in a recliner watching sports on TV -- and very quickly I realized the combination of slothfulness and power-verbs could only result in something very silly. So I let it become as silly as it wanted to be and this is the result.

Gord avalanched into his recliner. He grasped the TV remote and jabbed his thumb down on the button of power.

Rapid-fire images of commercial enticement cascaded and danced before his eyes. Gord dragged air in and out of his lungs. His mouth sagged open.

One image at last flung hooks of interest that caught hold of his eyes and tugged. Hockey. The blaring theme song called to his blood.

Gord burrowed into the creaking leather of the chair and watched, watched, watched.

The play ceased. The period break slammed into his absorption like a body check. Gord stirred in his chair. His domelike stomach emitted a deep, gurgling, rhinocerotic growl.

From a rotund bowl on the table at his side Gord captured a rippled chip of potato. His jaws snapped down upon it, his molars grinding, grinding. The heady savour of salt and caustic vinegar smacked his olfactory and gustatory nerve endings upside the head. Swiftly he snatched up another chip and crushed it into paste, then another and another.

With a decisive squeeze he wrenched off the unwilling cap of a cold brown bottle, tilted his head back and sluiced down a foaming, bubbling tide of Alberta-made big-name brand beer, his neck pulsing like a wild thing.

Hockey returned and again Gord watched with all his might, his capacious flesh jerking and rippling to the movements on the screen, grunts and other ejaculations of vicarious team spirit and zeal rising frequently from his throat. Come on!... Damn it!... Aww jeeziz guy!…Oh … oh … oh YEAH!

There were many exciting plays, and more beers cracked open and chugged down to toast them. At the appointed time the game ended, happily as it turned out for the team of Gord’s affections. The late evening news came on. There were a few broken bits of potato chip left in the bowl. Gord plucked them out and ate them, staring glassily at rapid-fire images of unpleasant happenings around the world. Then the sports news came on and Gord relived the night’s most exciting plays and cheered once more at that totally awesome goal.

With his tongue Gord zambonied the remaining crumbs and salt from his lips. A Brobdingnagian belch volcanoed up from the core of his being, followed by a face-cracking, leonine yawn that shook his mighty frame and shuddered down into his toes.

Once again, as he had before, Gord prodded the button of power. The screen went dark.

Silence bombarded the room like an aerial bombardment of very quiet warplanes.

Gord's eyes clanged shut like portcullises. He stampeded his way down into the beery vales of sleep.

Author's note: this piece began as a writing exercise about verbs. I wanted to see if I could make a very passive activity sound active and exciting by using strong, active verbs. I chose the most passive activity I could think of -- sitting in a recliner watching sports on TV -- and very quickly I realized the combination of slothfulness and power-verbs could only result in something very silly. So I let it become as silly as it wanted to be and this is the result.

Published on September 21, 2012 06:50

September 19, 2012

Harbinger

Tales from the Golden Goose: Harbinger

One of the last days of summer. The three of us were walking along the train tracks at the edge of town, bored and looking for something to do.

Kyle gave a shout. Amy and I followed him across a patch of waste ground and into the trees.

An abandoned car sat half-hidden in the tall grass. Most of the windows were busted and gone. The tires were flat. The seats were split open, the stuffing inside spilled out like guts. Kyle got to the driver’s door before me, wrenched it open and jumped in behind the wheel.

I hesitated, annoyed he’d beaten me to it. Amy climbed in beside him, which left me the back seat.

We’re the Mom and Dad and you’re the kid, Kyle said to me over his shoulder. So fashion your seatbelt and shut up.

We pretended we were going on vacation. We bounced up and down on the squeaky seats. Kyle pretended he was driving drunk and Amy pretended to be angry at him. I made some whiny little kid noises that made them both laugh, but my heart wasn’t in it. Kyle pretended he was sick of us and was going to drive us off a cliff. We pleaded and shrieked.

Then Amy shrieked for real.

A bee!

There was a bee in the car.

A bee! Shit! A bee!

We screamed and ducked and laughed. The bee buzzed around our heads, then flew out one of the broken windows and was gone.

Thank God, Amy breathed, and she leaned her head against Kyle’s arm. She’d never done anything like that before and I couldn’t tell if she was still playing the Mom. I was right behind them in the back seat but I felt as if I was in another room. I had no words yet for what I knew in that moment, for what I understood was coming to sunder me from them in the days ahead, but my heart knew and it began to pound in my chest like something trapped and frantic to escape.

Wait, listen, Kyle said.

There was still a buzzing. It was muffled, not loud, but still you could tell it was that big angry sound made by a whole swarm.

We looked around.

What the hell, Kyle said.

Where’s it coming from? Amy said.

I saw Kyle reach in front of Amy to open the glove compartment. I shouted for him to stop but I was too late.

One of the last days of summer. The three of us were walking along the train tracks at the edge of town, bored and looking for something to do.

Kyle gave a shout. Amy and I followed him across a patch of waste ground and into the trees.

An abandoned car sat half-hidden in the tall grass. Most of the windows were busted and gone. The tires were flat. The seats were split open, the stuffing inside spilled out like guts. Kyle got to the driver’s door before me, wrenched it open and jumped in behind the wheel.

I hesitated, annoyed he’d beaten me to it. Amy climbed in beside him, which left me the back seat.

We’re the Mom and Dad and you’re the kid, Kyle said to me over his shoulder. So fashion your seatbelt and shut up.

We pretended we were going on vacation. We bounced up and down on the squeaky seats. Kyle pretended he was driving drunk and Amy pretended to be angry at him. I made some whiny little kid noises that made them both laugh, but my heart wasn’t in it. Kyle pretended he was sick of us and was going to drive us off a cliff. We pleaded and shrieked.

Then Amy shrieked for real.

A bee!

There was a bee in the car.

A bee! Shit! A bee!

We screamed and ducked and laughed. The bee buzzed around our heads, then flew out one of the broken windows and was gone.

Thank God, Amy breathed, and she leaned her head against Kyle’s arm. She’d never done anything like that before and I couldn’t tell if she was still playing the Mom. I was right behind them in the back seat but I felt as if I was in another room. I had no words yet for what I knew in that moment, for what I understood was coming to sunder me from them in the days ahead, but my heart knew and it began to pound in my chest like something trapped and frantic to escape.

Wait, listen, Kyle said.

There was still a buzzing. It was muffled, not loud, but still you could tell it was that big angry sound made by a whole swarm.

We looked around.

What the hell, Kyle said.

Where’s it coming from? Amy said.

I saw Kyle reach in front of Amy to open the glove compartment. I shouted for him to stop but I was too late.

Published on September 19, 2012 06:12

September 17, 2012

The empty box

The Empty Box

The king told the youth, “If you want to marry my daughter you’ll have to bring me three golden hairs from the Devil’s head.”

The youth didn’t flinch or hesitate. He was in love with the princess and she with him. Nothing was going to stand in his way.

He set off immediately to find the entrance to Hell. It wasn’t easy. No one he met seemed to know where Hell was, exactly. They all had a vague idea that it was somewhere not too far away, but beyond that….

The youth met a soldier coming along the street on two crutches and asked him if he knew the way to Hell. The soldier swore at him. “If I wasn’t hanging off these sticks I’d give you a beating,” he growled. Then he looked the youth in the eyes and realized he was sincere.

“I’m sorry to tell you this,” the soldier said, “but Hell doesn’t exist.”

“What do you mean?” the youth asked in alarm.

“It’s just an idea that people made up a long time ago, to scare other people into being good. Lots of fools still believe in it, though. They’re sure it’s a real place, where anyone they don’t like or disagree with is sure to end up.”

The youth was desolate. “But I need there to be a Hell,” he said. “There has to be one.”

“Don’t worry, there are plenty,” the soldier said. “Try the hospital I just came from.”

The youth went to the hospital. It was noisy and crowded. Stretchers with sick and wounded people on them filled the hallways like a traffic jam. When he asked the patients, nurses and doctors if this was Hell, they all told him to go there.

“That’s what I’m trying to do,” he said in frustration.

Finally a man in a black suit told him he was looking in the wrong direction. Wherever you were on the planet, the man said, Hell was always in the same direction: down.

The youth found a staircase that took him to the lower floors of the hospital. At the bottom was a door. Through the door was another staircase that led down to a subway platform. The youth waited for a while and a train came and he climbed on board.

There were a few other passengers, but they didn’t speak or look up from their device-thumbing. Sitting across from the youth was a big, powerful-looking man with his tattoo-covered arms folded across his chest. He was wearing a huge, fully-loaded tool belt. He looked at the youth and then nodded.

“It’s real,” the man said. “I can tell you that from experience.”

“You know what I’m looking for?” the youth asked. “You’ve been there?”

“I work there,” the man said. “Paying off a mistake I made a long time ago. Otherwise believe me, I’d find another job in a heartbeat.”

“What do you do?”

The repairman smiled as if he knew a great secret.

“I need three golden hairs from the Devil’s head,” the youth said. “Will you help me get them?”

“Sabotage,” the repairman said. “I like it.”

The train made several stops, and one by one the other passengers got off, until only the youth and the repairman were left in the car. The train rolled and rattled on. Finally it stopped again. The repairman got out and the youth followed him. As the train pulled away, the youth saw that a terrible battle was going on in one of the other cars: a winged, radiant woman with a shining spear was fending off a thing that was all mouths and darkness. No one else sitting in that car seemed to notice or care.

The repairman and the youth ascended a flight of stairs and came outside into a street that blazed in the sun. No one was around. The repairman walked down the street and the youth followed him, to a large house with a big bay window and an attached garage. The repairman rang the doorbell and a voice said Come in.

The Devil was sitting in a leather recliner with the footrest up, watching television and eating a TV dinner of ham, mashed potatoes, and corn. He was fat, sweaty and balding.

“Who’s that?” the Devil asked, pointing to the youth.

“New trainee,” the repairman said.

“Well, get to it,” the Devil said.

The repairman went over to a metal box sticking out of the wall. He removed the front panel. There was nothing inside, as far as the youth could tell, but the repairman folded his arms across his chest and stared into the empty box with a look of intense concentration. He didn’t move for a long time, and the youth stole glances at the Devil.

The Devil was watching the news. It was all the same: bad. Then there was a commercial break. It was all the same: good. Then the Devil’s phone burbled.

“Hi, Ma. What’s that? Really? How’d it happen? Heart attack. Wow. Jeez. Yeah, I know, he was younger than me. Uh-huh. Uh-huh. Yeah, okay, Mom, I will. Sure. Uh-huh. Okay. Right. Uh-huh. Okay. Yep. Okay. Uh-huh. Okay, bye-bye.”

The Devil went back to watching television and eating his TV dinner. Somewhere in a faraway country a man who was angry put a gun to another man’s head and fired. The Devil fell asleep with the empty dinner tray rising and falling on his stomach with each breath.

The repairman said, “Ah.” He took a small pair of needle-nose pliers from his toolbelt and picked something from inside the box. He held it up for the youth to see. Between the jaws of the pliers was a tiny round object, either a pebble or a seed. The repairman dropped the object into a pouch on his belt, then gave the youth a wink. He took out a pen and marked the date on a sticker on the front panel of the box, then put the panel back in place.

“Now then,” he said, and went over to the Devil. He handed the pliers to the youth. There weren’t many hairs left on the Devil’s head, and most of them were grey. But the youth searched and managed to locate three that were gold. He plucked the first one, bracing himself for an eruption of absolute evil, but the Devil didn’t stir. And the hair came out easily. So did the other two. As if they were going to fall out soon anyway.

When the youth got home he discovered the king had flown into a rage about something or other and had died of a heart attack. There was no obstacle anymore to the young people’s marriage, but there had to be a mourning period first, to show respect for the king. During that time the youth and the princess discovered that they really didn’t have all that much in common. They parted amicably.

The three golden hairs are lying on a windowsill somewhere, forgotten. They are perfectly useless. No one notices how they shine in the sun.

-- Based on “The Devil with the Three Golden Hairs” by the Brothers Grimm. There’s a delightful retelling of the traditional story, called Ouch!, by Natalie Babbitt and Fred Marcellino.

The king told the youth, “If you want to marry my daughter you’ll have to bring me three golden hairs from the Devil’s head.”

The youth didn’t flinch or hesitate. He was in love with the princess and she with him. Nothing was going to stand in his way.

He set off immediately to find the entrance to Hell. It wasn’t easy. No one he met seemed to know where Hell was, exactly. They all had a vague idea that it was somewhere not too far away, but beyond that….

The youth met a soldier coming along the street on two crutches and asked him if he knew the way to Hell. The soldier swore at him. “If I wasn’t hanging off these sticks I’d give you a beating,” he growled. Then he looked the youth in the eyes and realized he was sincere.

“I’m sorry to tell you this,” the soldier said, “but Hell doesn’t exist.”

“What do you mean?” the youth asked in alarm.

“It’s just an idea that people made up a long time ago, to scare other people into being good. Lots of fools still believe in it, though. They’re sure it’s a real place, where anyone they don’t like or disagree with is sure to end up.”

The youth was desolate. “But I need there to be a Hell,” he said. “There has to be one.”

“Don’t worry, there are plenty,” the soldier said. “Try the hospital I just came from.”

The youth went to the hospital. It was noisy and crowded. Stretchers with sick and wounded people on them filled the hallways like a traffic jam. When he asked the patients, nurses and doctors if this was Hell, they all told him to go there.

“That’s what I’m trying to do,” he said in frustration.

Finally a man in a black suit told him he was looking in the wrong direction. Wherever you were on the planet, the man said, Hell was always in the same direction: down.

The youth found a staircase that took him to the lower floors of the hospital. At the bottom was a door. Through the door was another staircase that led down to a subway platform. The youth waited for a while and a train came and he climbed on board.

There were a few other passengers, but they didn’t speak or look up from their device-thumbing. Sitting across from the youth was a big, powerful-looking man with his tattoo-covered arms folded across his chest. He was wearing a huge, fully-loaded tool belt. He looked at the youth and then nodded.

“It’s real,” the man said. “I can tell you that from experience.”

“You know what I’m looking for?” the youth asked. “You’ve been there?”

“I work there,” the man said. “Paying off a mistake I made a long time ago. Otherwise believe me, I’d find another job in a heartbeat.”

“What do you do?”

The repairman smiled as if he knew a great secret.

“I need three golden hairs from the Devil’s head,” the youth said. “Will you help me get them?”

“Sabotage,” the repairman said. “I like it.”

The train made several stops, and one by one the other passengers got off, until only the youth and the repairman were left in the car. The train rolled and rattled on. Finally it stopped again. The repairman got out and the youth followed him. As the train pulled away, the youth saw that a terrible battle was going on in one of the other cars: a winged, radiant woman with a shining spear was fending off a thing that was all mouths and darkness. No one else sitting in that car seemed to notice or care.

The repairman and the youth ascended a flight of stairs and came outside into a street that blazed in the sun. No one was around. The repairman walked down the street and the youth followed him, to a large house with a big bay window and an attached garage. The repairman rang the doorbell and a voice said Come in.

The Devil was sitting in a leather recliner with the footrest up, watching television and eating a TV dinner of ham, mashed potatoes, and corn. He was fat, sweaty and balding.

“Who’s that?” the Devil asked, pointing to the youth.

“New trainee,” the repairman said.

“Well, get to it,” the Devil said.

The repairman went over to a metal box sticking out of the wall. He removed the front panel. There was nothing inside, as far as the youth could tell, but the repairman folded his arms across his chest and stared into the empty box with a look of intense concentration. He didn’t move for a long time, and the youth stole glances at the Devil.

The Devil was watching the news. It was all the same: bad. Then there was a commercial break. It was all the same: good. Then the Devil’s phone burbled.

“Hi, Ma. What’s that? Really? How’d it happen? Heart attack. Wow. Jeez. Yeah, I know, he was younger than me. Uh-huh. Uh-huh. Yeah, okay, Mom, I will. Sure. Uh-huh. Okay. Right. Uh-huh. Okay. Yep. Okay. Uh-huh. Okay, bye-bye.”

The Devil went back to watching television and eating his TV dinner. Somewhere in a faraway country a man who was angry put a gun to another man’s head and fired. The Devil fell asleep with the empty dinner tray rising and falling on his stomach with each breath.

The repairman said, “Ah.” He took a small pair of needle-nose pliers from his toolbelt and picked something from inside the box. He held it up for the youth to see. Between the jaws of the pliers was a tiny round object, either a pebble or a seed. The repairman dropped the object into a pouch on his belt, then gave the youth a wink. He took out a pen and marked the date on a sticker on the front panel of the box, then put the panel back in place.

“Now then,” he said, and went over to the Devil. He handed the pliers to the youth. There weren’t many hairs left on the Devil’s head, and most of them were grey. But the youth searched and managed to locate three that were gold. He plucked the first one, bracing himself for an eruption of absolute evil, but the Devil didn’t stir. And the hair came out easily. So did the other two. As if they were going to fall out soon anyway.

When the youth got home he discovered the king had flown into a rage about something or other and had died of a heart attack. There was no obstacle anymore to the young people’s marriage, but there had to be a mourning period first, to show respect for the king. During that time the youth and the princess discovered that they really didn’t have all that much in common. They parted amicably.

The three golden hairs are lying on a windowsill somewhere, forgotten. They are perfectly useless. No one notices how they shine in the sun.

-- Based on “The Devil with the Three Golden Hairs” by the Brothers Grimm. There’s a delightful retelling of the traditional story, called Ouch!, by Natalie Babbitt and Fred Marcellino.

Published on September 17, 2012 07:40

September 14, 2012

The knife-thrower's new girl

Tales from the Golden Goose: The knife-thrower's new girl

When I was young I ran away from home and joined a circus. The circus master was a dwarf with rings on all his fingers and in his ears. He looked me up and down and said that since I was so skinny I should work with the knife-thrower. The knife-thrower needed a new girl anyhow, he said.

What happened to the last girl? I asked.

There was … an accident, the circus master said.

I didn’t ask him what sort of accident. I’d used up most of my nerve just leaving home. I didn’t want to hear anything that might send me running back there.

I found the knife-thrower practicing in a tent. I watched him for a while before he noticed me. He was beautiful. He was like a knife himself. His sleek dark hair was the hilt, his lean golden body the blade. I imagined if I touched his cheekbone I’d cut myself.

Every evening I wore a blindfold and a red gown and I spun on a wheel and the knife-thrower threw his knives at me. When he’d thrown them all the people would applaud and cheer and I would climb down from the wheel and take a bow with the knife-thrower. When I looked behind me there was the outline of my body in knives.

Many women came and went from the knife-thrower’s caravan, but he never invited me. Never touched me. He only talked to me when he’d been drinking. One night he said, I’ll tell you a secret. I can only throw knives at someone I don’t love and who doesn’t love me. That’s why I need you. If we fell in love, I would lose my nerve and I could hurt you.

What happened to your last girl? I asked. He didn’t answer. I went and took a closer look at the wheel. A few of the holes made by all those knife-tips, night after night, traced out my skinny girl shape. But most of the holes traced the lines of someone more curvy, more a woman. In the centre of the wheel there was only one hole. Where her heart would be. And mine.

Every evening he threw his knives and made the shape of my body on the wheel. Every night I cried alone in my bed and hated him. Then one evening I ran away from the circus, and joined another circus. I married the circus master, a dapper man with a gold pin. Now I sit in a cage outside the big tent and I take people’s coins.

Some nights I wake up in my bed and it is spinning, spinning.

When I was young I ran away from home and joined a circus. The circus master was a dwarf with rings on all his fingers and in his ears. He looked me up and down and said that since I was so skinny I should work with the knife-thrower. The knife-thrower needed a new girl anyhow, he said.

What happened to the last girl? I asked.

There was … an accident, the circus master said.

I didn’t ask him what sort of accident. I’d used up most of my nerve just leaving home. I didn’t want to hear anything that might send me running back there.

I found the knife-thrower practicing in a tent. I watched him for a while before he noticed me. He was beautiful. He was like a knife himself. His sleek dark hair was the hilt, his lean golden body the blade. I imagined if I touched his cheekbone I’d cut myself.

Every evening I wore a blindfold and a red gown and I spun on a wheel and the knife-thrower threw his knives at me. When he’d thrown them all the people would applaud and cheer and I would climb down from the wheel and take a bow with the knife-thrower. When I looked behind me there was the outline of my body in knives.

Many women came and went from the knife-thrower’s caravan, but he never invited me. Never touched me. He only talked to me when he’d been drinking. One night he said, I’ll tell you a secret. I can only throw knives at someone I don’t love and who doesn’t love me. That’s why I need you. If we fell in love, I would lose my nerve and I could hurt you.

What happened to your last girl? I asked. He didn’t answer. I went and took a closer look at the wheel. A few of the holes made by all those knife-tips, night after night, traced out my skinny girl shape. But most of the holes traced the lines of someone more curvy, more a woman. In the centre of the wheel there was only one hole. Where her heart would be. And mine.

Every evening he threw his knives and made the shape of my body on the wheel. Every night I cried alone in my bed and hated him. Then one evening I ran away from the circus, and joined another circus. I married the circus master, a dapper man with a gold pin. Now I sit in a cage outside the big tent and I take people’s coins.

Some nights I wake up in my bed and it is spinning, spinning.

Published on September 14, 2012 07:36

September 12, 2012

Back to life Part 2

The hanged man’s neck is broken and so I have to cradle his head in the crook of my arm to hold it upright. Then I reach my fingers around to the mouth. I don’t want to touch those cold lips, that swollen tongue, but I think of the gold and I force myself.

The jaw is already getting stiff, so I have to yank on it hard, and I hear it crack. Then the old fellow crouches down and brings the bottle to the dead man’s lips and starts to pour the contents slowly and carefully down his throat. Whatever this stuff is, it smells worse than goat piddle left to ferment in a bucket all summer. And all the while he’s pouring, the old one is murmuring to himself, like someone reciting his prayers.

“Life is heat, and motion, and impulse,” he’s saying. “Impulse is the physical manifestation of desire, and desire is not only of the corporeal body but of the spirit. The salamandrian fire does not originate within the body but the body takes part in it…”

The concoction is all gone. The old fellow slips the empty bottle back into his cloak and hunches forward, peering closely into the corpse’s face.

“Nothing’s happening,” I say.

“Patience,” the old one says, and then he looks up at me sharply. “You believe you have a soul in you?”

“I don’t know. That’s what the preachers say.”

“Tell me this, if the soul is incorporeal, insubstantial, if it is not physical matter, how could it be confined by time and space? Why would it have to be in you at all? No, my friend, our lives are moved by a great cosmic force called desire. We think of our desires, like our souls, as part of us, as something growing from us like our hair and teeth, but desire is larger than any of us. It’s an invisible river that we all swim in. It surrounds us and shapes us, but like stones in a stream we also give a shape to desire. We leave our own particular traces in the current. Those traces are still here, lingering around the body.”

He returned his gaze to the dead man, frowned, and prodded the cold, bare chest with a finger.

“All that the elixir does is restore heat and motion to the physical shell. The rest is accomplished by desire. The body seeks the same things it did in life. And what did he want more than anything in this life?”

“Gold,” I say, and the dead man jumps. As if the word itself was all he was waiting for, he flops in my arms like a fish. I give a shout and I’m about to drop him but the old fellow raises a hand.

“Don’t be afraid,” he says. “It’s just life. Life returning.”

He’s not afraid, clearly, and something in me doesn’t want to look a coward in his eyes, so I hang on to the dead man. If he is a dead man anymore. And if he isn’t, then what is he?

I cry out again when the dead man’s hand reaches out and clutches my arm.

“Papa,” says a voice that I can still hear, all these years later. A voice that seems to be coming from a cave deep underground, though it’s coming from the dead man’s throat. “Papa, is that you?”

I look at the old fellow, and he nods. I understand what he wants me to do. I swallow hard.

“Yes,” I say. “It’s me, son.”

“I want to come home Papa. I’m so sorry for what I done. Please let me come home.”

I look at the old fellow and he mimes rubbing a coin between his fingers.

“You can come home, son,” I say, “as soon as you tell us where you hid the gold.”

The voice rises again out of its deep hole.

“Don’t let them hang me, Papa. I’m sorry. I want to come home.”

“The gold.” My voice is harsh, but not because I’m angry at him. I’m angry at myself. I’m disgusted with myself, but I can’t stop. “Where did you hide the gold?”

He growls and he moans and he thrashes in my arms, but in the end he tells us. He gives us the precise location in great detail, so we won’t have any trouble at all finding it. And once the old fellow has the information he’s after, he whispers to me, “Now put him back.”“What?”“He has to go back in the ground so no one will know.”“But he’s alive.”“You call this life? No, the elixir’s potency will fade in a few hours and the body will go cold again. He’ll begin to rot, just as nature intended.”“You’re sure?”“If the elixir brought the dead back to life and kept them alive permanently, why would I need to dig up graves in the middle of the night? Think, man. I could just sell the elixir and get rich that way.”That made sense, I suppose. I lean close to the dead man’s ear and I whisper, “You’ve done well, son. You’re home now, and you can rest. So rest now. Sleep.”The dead man lets out a long sigh, but doesn’t speak again, or move. His hand lets go its grip on my arm.

And yes, I buried him. Tied the sack back around him like I was tucking him in for the night. Put him back in the ground and covered him over. And then the old fellow and I went to the place where the dead man had hidden the gold, and we found it all right. The old fellow honored his word. He shared the gold with me and I was able to buy the tavern and set myself up for life. As for the sorcerer, never heard a word of him after that night.

A happy ending? Things went my way for a while, it’s true. Sure, it was a mystery where a gravedigger had found enough money to set himself up in business, but because no one could prove anything, I was safe. But even though I was on the other side of the bar now, filling the glasses and raking in the coins, the drink was still right in front of me and I couldn’t keep myself from it. At the end of each night, after the last of my customers had staggered home and I was cleaning up, I’d look toward the door and expect to see him there. Come for what he wanted more than anything in this life. That thought was enough to drive a man to the bottle. And in time I lost everything: tavern, wife and child.

You call this life? I haven’t forgotten the question. He wasn’t speaking of me, but he might as well have been. Heat, motion, and impulse. Did I live any better than the man I put back in the ground?

So that’s what magic does. That’s what magic is. There’s always a price to pay for the thing you want more than anything in this life. You find out who you really are.

Published on September 12, 2012 06:33