Thomas Wharton's Blog, page 12

August 14, 2012

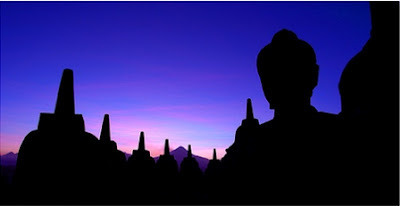

Borobudur

When I was a young student backpacking through Asia, I witnessed a wonder.

It happened at Borobudur, an ancient Buddhist temple on the island of Java. I was with a crowd on a hilltop. We were waiting for an eclipse.

Borobudur is the world’s largest Buddhist temple. Even if there hadn’t been an eclipse, this place would have been worth seeing. It was built sometime in the eighth century and abandoned about a hundred years later, as a result of increased volcanic activity, which eventually buried the site. It wasn’t until the nineteenth century that Borobudur was rediscovered, by a British expedition led by Sir Thomas Raffles. (His name was also given to the world’s largest flower, Rafflesia, which bursts into full bloom only in the middle of the night, during the rain).

When I first got there the temple grounds were already swarming with people, singing songs and playing music, eating and drinking, selling and buying food and t-shirts and pieces of smoked glass. It looked like a carnival.

The eclipse wasn’t scheduled to start for hours so I joined a guided tour of the site. I found out that the temple has three levels, each corresponding to a plane in the Buddhist cosmos. Kamadhatu, the lowest level, was the realm of human passions and impulses. “Also known as the world of illusion,” said our guide, a pretty young woman who smiled a lot at one member of the tour group, a handsome young man.

Ruphadhatu, a level of ornamented terraces, depicted in stone the life of Prince Siddhartha Gotama, who became the Buddha.

Arupadhatu, the highest level, was that of absolute knowing and freedom from desire. We didn’t stay long at this height.

Pilgrims walk around the entire structure from the bottom to the large stupa at the summit, to symbolize the journey from illusion toward enlightenment. At one point the guide gave a short talk on the life of Siddhartha.

“The Buddha made clear the three reasons for human suffering,” she said. “Being born, falling ill, and dying.”

All of life held in those six words. As simple as that. All I knew about Buddhism up to this point came from an article in our outdated World Book encyclopedia at home. It was a religion that declared nothing was real, according to the article. I'd never liked the sound of that.

Later I joined a large group of tourists and locals waiting on a nearby hillside for the eclipse. Someone gave me a piece of welding glass to look through. We waited, and people began to fidget and horse around as the minutes went by and nothing happened. Then someone gave a shriek and we all looked up. The moon, which had been invisible as it climbed near the sun, had become a stark black notch on the white-hot solar disc.

No one spoke. The children who’d been tearing around and chattering went still, like their parents. As totality approached, a vast shadow fell and swallowed everything, the impossible indigo shadow of the end of the world.

All was utter stillness. There was no hour on the clock for this no-night, no-day. A fierce, multicoloured corona burst out all around the sun, so intensely bright that even through the dark glass I could hardly bear it.

We had been transported to an alien planet. Everything we knew was gone.

The light came back. The world came back. We set aside our goggles and cameras and looked at one another. Some were weeping, others laughing and hugging strangers, like friends who haven’t met for years.

For a moment we were not from different countries, different cultures, different religions. We were just here, together, on a world that was beautiful and mysterious and terrifying beyond words. It occurred to me I should probably find out more about Buddhism.

But not now. Now it was time to climb back down to Kamadhatu. To find something to eat, and phone home.

Published on August 14, 2012 07:17

August 10, 2012

Folk fest koan

Summer music festival on the old ski hill. A snow of people.

The music rolled up the hill, defying gravity. Surrendering to the body, I went down for a samosa.

Beside the main stage, nature goddesses dancing.

Why isn’t every city like this all the time?

Climbing back up into a wave of blue tarps I was lifted by the music and lost my way.

So that’s how you get into heaven.

I couldn’t find my row. I couldn’t find my tarp. It was blue.

What a gift uncertainty is.

Published on August 10, 2012 07:50

August 7, 2012

The elements of story: fire

The elements of story 4: fire

If water is the flow of a good story, and earth gives a story weight and substance, and air is the freedom of the storyteller’s art, then fire is the imagination itself. The energy that creates worlds.

To tell the story of fire is to tell the story of everything and how it came to be. The universe itself, we're told by the storytellers we call scientists, began in a burst of fire. Whether there was an Author behind it or not, this universe is an unfinished, always astonishing act of creativity. Just look at a lilac bush, or a sunset, or a giraffe.

The universe came up with stars, galaxies, planets, life, and then it really got going and dreamed up a being that could create universes inside its own head, share them with others, and change the way things are. A being who can tell new stories.

That’s the incredible gift and power a storyteller has at her command. A trace of the fear and reverence that used to be felt for those who wield this creative fire survives in the way we still regard authors as slightly mysterious beings. The difference being that we used to be in awe of the power of their art, but now we respect them only if they make lots of money.

Both attitudes miss the point. The fire is something meant to be passed on, from mind to mind, to be shared by all. We all have this creative fire in us. We all have the power to transform the world.

In the Perilous Realm trilogy, the spark of creativity is called the fathomless fire. It can be used for good, or it can be used for selfish reasons, to control others. The battle for the Realm coming in Book Three of the trilogy is a struggle between these two ways of wielding the power of story.

Coming soon: a post about the mysterious fifth element of story.

Published on August 07, 2012 07:08

August 3, 2012

The elements of story: air

The elements of story # 3: air.

Our revels now are ended. These our actors,

as I foretold you, were all spirits and

are melted into air, into thin air….

-- Shakespeare, The Tempest

Prospero, the magician in Shakespeare’s The Tempest, is a brilliant storyteller. Almost the first thing we see him doing in the play is telling his daughter Miranda the story of how the two of them came to live on this enchanted island. He tells it with such skill and power that Miranda exclaims “Your tale, sir, would cure deafness.”

But the story he tells doesn’t have an ending … yet. The play that unfolds before us is the completion of that unfinished story. From start to finish we see Prospero, with his magical art, in control of everything that happens. He carefully shapes events in order to weave a happy ending, and the element he uses most in his story-shaping is air.

The chief spirit under his command, Ariel, not only has an airy name, he is mostly air himself. Ariel “performs” the storm which brings the ship carrying Prospero’s treacherous brother Antonio to the island. At Prospero’s bidding he creates lifelike visions that beguile or frighten, and just as quickly makes them dissolve. Like air, he seems to be able to go anywhere -- he has no physical limitations, other than Prospero’s power over him. (Of course Prospero has another servant who is far more solid and far less willing: Caliban, whom he refers to at one point as “thou earth.”) After one of Ariel’s visions has suddenly vanished, Prospero tells Ferdinand that the spirits have melted into thin air. He then goes on to say that everything in the world will eventually do the same, since “we are such stuff as dreams are made on.”

Air, then, is the boundless freedom of the storytelling mind, constrained only by the storyteller’s skill and vision. Air is the breath of inspiration, by which the maker of story reimagines and shapes experience into the stuff dreams are made on. And air is the word, uttered by the breath, or spoken silently in the reader’s thoughts, which weaves the “baseless fabric” of a story.

Published on August 03, 2012 07:48

July 30, 2012

The elements of story: earth

The elements of story # 2: earth

Earth is solid. It’s heavy. Thick. We can’t see through it. We stub our toes on it. We’re held to it by gravity.

There’s always something in a story that’s like this. A good story isn’t all on the surface. There’s some mysterious force that pulls us in and holds us. A good story might even make us stumble. And sometimes we have to do some digging to find its treasures.

Here’s a story made of earth:

No one wants to die, and the emperor was no exception. It wasn’t right -- that the most powerful man in the world was powerless to avoid that solitary journey into the darkness.

“If we must go, we will not go alone,” the emperor told his counselors, using the royal we. “We will take our people with us. On the day we die, ten thousand soldiers, officials, astrologers musicians, acrobats are to be killed and buried with us.”

The counselors knew that if word of this plan got out there would be an uprising and they would likely lose their heads, one way or another. With great tact and much obsequiousness they managed to convince the emperor to change his plans. Instead, ten thousand figures of men (and a thousand or so horses) would be fashioned of fired clay and placed in the emperor’s tomb with him.

And so it was done, because in that empire the more absurd and impossible an idea was the more likely it was to become a reality. Thousands of men worked for years on the project so that by the time the emperor died, the making of these thousands of clay warriors and other court personages had been completed, and an underground imperial city had been built to house them. The emperor was laid to rest in a silent palace surrounded by silent courtiers who would be loyal to him through eternity.

(Incidentally, no one knows how many workers died in the delving of this great city of the dead, just as no one knows how many died in the other impossible, childlike idea of building a wall around the empire.)

Grass grew over the tomb, and dynasties fell and rose and fell again. In time the kingdom forgot about the emperor’s subterranean army, until one day in the late twentieth century when a farmer digging in his field unearthed one of the clay men. Since then hundreds of men and horses and chariots made of baked earth have been released from their tombs and stand in ranks for all to see. This is the army that protected the people from their own emperor. From his fear of being alone after death.

Published on July 30, 2012 06:19

July 26, 2012

The elements of story # 1: Water

What is a story made of? Most readers, writers and critics (or story gurus these days) would probably list things like plot, setting, character, conflict, resolution. Some might add theme, atmosphere, style….

When we think about what a story is made of, these and a handful of other concepts are what usually come to mind.

These elements are time-tested and useful. But what if we took the idea of an element back to one of its oldest meanings? That of the four fundamental constituents of the universe: earth, fire, water, and air.

What if we imagined a story was created out of these elements? What might we notice about stories that gets obscured by relying on the same old familiar terms?

1. Water

Look at waves rolling into the shore. What story do they seem to be telling?

Our bodies are mostly water. We’ve all heard this fact so often that we rarely stop to think about how strange it is. And when we do think about it, we usually imagine water as an inert substance that a living thing makes use of to, well, live. There’s a lot of water in me, okay, sure, but Iam not water.

But if most of what constitutes this thing I call meis water, then really, I am water. I’m water with some other stuff coming along for the ride. And so are you. So is every living thing. Maybe we should classify living things as a means that water has found to circulate more widely and freely. And in human beings, water found a way to be creative, and reflect upon itself.

A story is something told by water.

So, if I’m not wading in too deep here, maybe the way to make a good story is to be as much like water as we can in the telling.

I find the Tao te ching useful for thinking about this (as it is useful for thinking about so many things).

This is from a version of Lao Tzu's timeless book by Ursula K. Le Guin, a writer who knows a few things about the flow of a good story:

True goodness is like water.Water is good for everything.It doesn’t compete.

It goes right to the low loathsome places,and so finds the way.

I thought I’d try putting some of these ancient ideas into story terms. Here's my version of some lines from the Tao:

A good story is like water,

which nourishes all things without trying to.

It’s at home in the low places that people disdain.

And yet water is powerful.It can gather strength quietlyuntil it is able to move mountains.

In your storymaking, be like water.

In imagining, stay close to the earth.

In description, keep to the simple.

With your characters, do not take sides.

When plotting, don't try to control.

Let all things happen when the time is right.

Next post: The elements of story # 2: Earth.

Quotation from Lao Tzu: Tao Te Ching: A Book About the Way and the Power of the Way, by Ursula K. Le Guin. Shambhala, 1998.

Published on July 26, 2012 22:36

July 24, 2012

On being an Alberta writer

I have a complicated relationship with the place I live. I was born in northern Alberta, I’ve lived in one place or other in the province all my life, and I don’t really see myself moving elsewhere. But I’ve always felt out of place here, to some degree.

Growing up in the oil and gas boomtown of Grande Prairie, I knew almost no one else my age who really liked reading, let alone writing, and so I rarely talked about these interests of mine with anyone. I did have a few book-loving friends, like John, whose family had moved from England. One day I pulled a book from his shelf that I was curious about and flipped through its pages. “What’s a hobbit?” I asked. “You should read that,” he said. “It’s really good.” I did read it. He was right. I went on and read the rest of that author’s books. No, better to say I devoured them. Or they devoured me. New vistas of story opened up for me with Tolkien’s books. Here was a writer who had created an entire world, and I wanted more of that kind of thing. I wanted books that would overwhelm, challenge, and change me. That desire took me from fantasy and science fiction to Dickens, Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Woolf, Orwell, Joyce, Calvino, Borges, Pynchon, Ondaatje …

Now I think it’s a good thing for a writer to be born in the wrong place. Maybe all writers are, or feel themselves to be, and that’s one of the reasons why we write. There’s a lot about the politics and culture of this province that makes me weep -- for what we’re throwing away, what we’re ignoring and destroying in our pathological stampede for wealth and power.

But I love this place, too, and even though I don’t write about it directly a lot of the time (I write fantasy for the most part), I suspect that in all sorts of ways I don’t even notice, Alberta shows up in my work (come to think of it, there's a pathological stampede for power in my current fantasy trilogy...).

Our seasons. Our weather. Our landscapes. Our cityscapes. Our distance from the so-called centres of our so-called civilization. Even something like the kind of light we get here probably has more of an impact on the way I see the world than I realize.

Published on July 24, 2012 20:09

July 23, 2012

Landscape with a woman

As a kid I wondered why the painter had stuck this boring woman in front of one of the most mysterious, enticing landscapes I’d ever seen.

I first saw da Vinci’s Mona Lisa in a coffee table book about Western art that we had at home when I was a kid. I loved that book and poured over the famous paintings in it over and over again. I looked at the Mona Lisa many times, but I wasn’t really interested in the woman. To me she looked old. I didn’t know I was supposed to find her tepid half-smile fascinating and enigmatic. I thought her hands were kind of nice -- soft and gentle-looking -- but for the most part she bored me.

But that landscape behind her. It was odd. For one thing its left half didn’t really match its right half. I didn’t know about perspective and vanishing points back then but it seemed that the body of water on the right should have been lower down than it was, in order to “fit.” My eyes couldn’t make the two halves of the landscape come together properly, but I thought the flaw, if there was one, must be with my seeing, not with the painter’s skill, since this painting was in a book of famous art.

So the landscape bugged me. But it also drew me in and enchanted me. It was strange and otherworldly and it was a place I wanted to go to. It looked as much like a map as it did a landscape. I felt I had been there before, on that road winding up into those jagged blue mountains, like mountains on some alien planet. I drew my own pictures of mysterious mountainous landscape with roads winding up into the distance. I’ve even had dreams where I find myself walking in that landscape. In the dream I usually meet someone on the road. There’s a feeling of anticipation and danger, as in myths and fairy tales, where every encounter on a road is meaningful and opens up the next part of the story.

There’s something happening in the part of that landscape we can’t see because the woman is in the way. Maybe da Vinci painted it like this on purpose, to make us feel there is a riddle here, and an answer to the riddle, hidden behind the woman who is also a riddle. The answer to the question of how those two halves of the landscape really come together, perhaps. Or maybe something more.

I finally got to see the real painting many years later, when my wife and I took a trip to Paris. Wandering the halls of the Louvre as evening fell, we felt we were descending deeper and deeper into a dreamlike state in which the sculptures and paintings were numinous, beckoning presences. And then the Mona Lisa. It was a disappointment. I'd seen it too many times already in books, on TV, on coffee mugs....

The painting hanging in the Louvre was so astonishingly small (is this the real painting?). I couldn't get close enough to it to see anything I hadn't seen before. And the woman was still blocking my view.

Published on July 23, 2012 06:13

July 19, 2012

The town and the wild

As a teenager living in Jasper I used to go for long solitary walks in the woods and surrounding hills. I never worried about bears in those days. It wasn’t until I grew up and had kids that I developed a real fear of meeting bears on the trail. Maybe because now I had someone else to stay alive for.

On those walks I used to wonder where the dividing point was, exactly, between the town of Jasper and the wilderness that surrounded it. I was sure there had to be such a boundary, though I was never sure when I had crossed it.

If you took even a few steps away from the paved streets, you were already heading into the wilderness, but when did you actually arrive there? The park had many well-used trails, and of course there were always nearby roads and power lines and warden stations and other markers of human presence. (And it always seemed odd to say that one was heading into the wild. As if the outside was somehow also an interior.) I liked to imagine that the boundary was the railroad track at the edge of town. It was a definitive line. The sight of it reassured you that you were still in the civilized world, where there was nothing that wanted to eat you. Once on the other side, all bets were off.

But in fact the wilderness never felt entirely wild, no matter how far or deep I went into it. For one thing I could never forget this was a national park, a fact that all by itself seemed to sap some of the “wild” out of one’s surroundings. This was a tended, guarded, in some ways controlled wilderness. It was a part of the rest of the world. Airplanes flew over it. Pollutants from elsewhere fell on its snowfields and trickled down into the rivers. People had colonized it, inhabited it, storied it.

But the town was never completely non-wild, either. Living in Jasper was a bit like living in a house with all the doors and windows wide open. Deer grazed on the streets, much to the delight of the tourists and annoyance of anyone with a garden in their yard. Bears and coyotes prowled in the back alleys for garbage (heading home late at night from a friend’s place more than once I met a bear on the street. We both ran). One summer there was a mountain lion living under a house trailer and preying on neighbourhood dogs to feed her cubs. Then there was the time a black bear strolled into the lobby of one of the hotels. The panic that ensued was shared by both bear and hotel guests.

One night was sitting at the kitchen table doing my homework when something tapped on the window. I looked up and gave a shout of terror to see an impossibly gigantic hand reaching toward the glass. An instant later I realized what I was seeing: the antler of an elk grazing peacefully at the side of our house. And that adrenaline pumping through my body after the scare I’d had: that was the wild within me, an animal response inherited from millions of years of evolution.

Eventually I came to see that there was no boundary between the town and the wild. Or if there was, it was almost entirely a mental one manufactured by my human mind, always striving to put the messy world into neat, manageable, conceptual boxes. Living in Jasper had shown me the porous, semi-imaginary nature of all borders and boundaries, though it took me a while to learn the lesson. If you look at anything carefully enough to find the dividing line between it and something else, it gets harder to find. It’s as true of oneself as of anything else. You can witness it happening every time you take a breath.

Maybe that’s why, as a writer, I so often write about those moments when one thing becomes something else. When things change their skin and reveal themselves to be other, or more, than what they seemed to be. I look for a contrast, an edge, a border, a boundary, and I start writing there, and the boundary opens up and reveals a dynamic, fluid, constantly changing space I can only attempt to trace with words.

Published on July 19, 2012 13:53

July 16, 2012

The Mares of Thrace

I admit it, I’m a bit afraid of horses.

My wife loves them. She rides as often as she can, and sometimes I go out with her to the stable, but I don’t ride. I think my fear stems from an incident that happened years ago when we were riding together and came to a steep, muddy embankment. Sharon dismounted to better lead her horse down the slope, but she slipped and fell, and her horse got spooked and took off running. The horse I was on obeyed its herd instinct and took off after the other one. So there I am galloping down the trail, completely NOT in control of the horse, with Sharon left way behind. I hung on for dear life until we came out into an open field and the lead horse finally stopped. My horse did too. No harm done, but since then I've had a very healthy respect for the unpredictability of these animals. I've even ridden a few times since, but generally I keep my distance.

Fear of horses probably isn’t all that common simply because most of us aren’t around horses anymore at all. If you have hippophobia it’s pretty easy to avoid confronting your fear.

But back in the days when the horse was the cutting-edge of transportation technology, people were around horses a lot. And there must have been much fear of horses, judging by myths like that of the mares of Thrace.

The four savage, man-eating mares belonged to King Diomedes of Thrace. According to Robert Graves, “Diomedes kept the mares tethered with iron chains to bronze mangers, and fed them on the flesh of his unsuspecting guests.” It was the eighth (and little-known) labour of Heracles to capture and tame these mares. He did so, eventually, by clubbing Diomedes over the head and feeding him to his own horses. No surprise that Disney omitted this part of the story from their version of Hercules.

It's tempting to see a survival of horse-fear in our own language, in the word "nightmare." But "mare" in this word actually comes from an Anglo-Saxon word for an evil spirit and has nothing to do with horses.

Published on July 16, 2012 07:39