Karl Shuker's Blog, page 39

April 11, 2015

EXPOSING THE 'DEAD BIGFOOT PHOTO' - THE BEAR FACTS AT LAST! - A SHUKERNATURE WORLD-EXCLUSIVE!

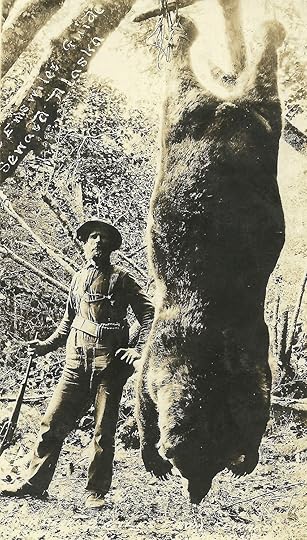

The infamous 'dead bigfoot photo' (origin unknown)

The infamous 'dead bigfoot photo' (origin unknown)On 21 November 2006, after having received it from a reader with the user name 'captiannemo', Craig Woolheater posted on Cryptomundo the very intriguing photograph opening this present ShukerNature blog article, and which has since become popularly referred to as the 'dead bigfoot photo', together with a request for any information available concerning it.

In view of its very striking, tantalising image, the photo attracted much interest, and was subsequently reposted twice by Loren Coleman on Cryptomundo (16 and 22 April 2009) with further requests for information. It has also been featured on many other websites. Yet although numerous opinions have been aired as to what it depicts (a shot bigfoot, bear, gorilla?) and whether or not it is authentic or photo-manipulated, no conclusive evidence as to its true nature has ever been obtained and presented - until now!

Earlier today, Facebook cryptozoological colleague Tony Nichol brought the following vintage picture postcard to my attention:

Vintage picture postcard depicting a hunter and shot Alaskan grizzly bear (purchased on ebay and now owned by Dr Karl Shuker – all rights reserved)

Vintage picture postcard depicting a hunter and shot Alaskan grizzly bear (purchased on ebay and now owned by Dr Karl Shuker – all rights reserved)With an example of it available for purchase on ebay's USA site, it depicted a shot grizzly bear, photographed in Seward, Alaska, and dating from the time period 1904-1918 - and as could instantly be seen, this was unquestionably the original image from which the bigfoot version had been created by photo-manipulation. After almost a decade, and as revealed here in this ShukerNature world-exclusive, the mystery of the 'dead bigfoot photo' is finally solved - except of course for discovering the identity of whoever created it from the vintage bear image.

To ensure that the latter does not become another 'missing thunderbird photo', however, I have actually now purchased the example of it available on ebay, and should be receiving it in the post shortly. Incidentally, the ebay wording present on the image of it contained in its ebay auction and shown above is naturally not on the actual postcard photograph itself, so once I have the postcard I'll include it in a more detailed documentation of the 'dead bigfoot photo' that I am currently preparing.

Perhaps I should also begin scanning ebay for the missing thunderbird photo ?!

Meanwhile, my sincere thanks go to Tony Nichol for kindly bringing the bear postcard to my attention, and, in so doing, enabling me to bring the lengthy reign of yet another cryptozoological pretender to its richly-deserved end.

The original bear photograph alongside the derived, photo-manipulated 'dead bigfoot photo' (bear photo owned by Dr Karl Shuker – all rights reserved)

The original bear photograph alongside the derived, photo-manipulated 'dead bigfoot photo' (bear photo owned by Dr Karl Shuker – all rights reserved)

Published on April 11, 2015 13:01

April 3, 2015

FROM LAMBTON WORMS AND SHAGGY BEASTS TO SOUP DRAGONS AND Q – A DRACONTOLOGICAL TOP TEN ON SHUKERNATURE

Official movie poster from the 1982 film Q – The Winged Serpent (© Larry Cohen (dir.)/United Film Distribution Company)

Official movie poster from the 1982 film Q – The Winged Serpent (© Larry Cohen (dir.)/United Film Distribution Company)As the author of two books on dragons – Dragons: A Natural History (1995) and Dragons in Zoology, Cryptozoology, and Culture (2013) – I've researched an extremely wide range of these reptilian monsters in my time. So here, excerpted from my two books, and in no particular order, are ten of my all-time favourite dragons and dragon-related subjects – a very diverse selection drawn from mythology, literature, and the media. And what more fitting, timely example with which to begin it than the Lambton worm, whose story supposedly began one Easter, long long ago…

THE LAMBTON WORM – AN ACCURSED BRITISH SERPENT DRAGON

The term 'dragon' is widely believed to derive from the Greek word 'derkein', which translates as 'sharp-eyed', and seems to have been applied originally to a snake. When transliterated into Latin, it became 'draco' – 'giant snake'. This is particularly apt because, morphologically, the basal dragon form was the serpent dragon. As its name suggests, in overall appearance this form, which was both limbless and wingless, resembled a huge snake or even a gigantic worm. Indeed, some serpent dragons were actually referred to as worms, also known as wyrms (an Old English term for snakes), wurms, or orms – all of which are terms derived from the Norse 'ormr' or 'ormer', translating as 'dragon'. Unlike these humble, harmless beasts, however, and betraying its draconian status, a serpent dragon had a head that was horned, long-jawed, and very often bearded.

Many of Britain's dragons were of the worm variety, which was also recorded widely across northwestern Europe. Dragon-headed and generally of immense length, worms not only lacked limbs and wings but also one of the characteristics most readily linked with dragons – the ability to breathe fire. However, this did not make them any less deadly – far from it. Instead of fire, worms emitted noxious clouds of poisonous gas that could lay waste to great swathes of countryside and decimate entire villages, or possessed a venomous bite of lethal propensity.

Worms could also kill by wrapping their huge coils around any potential antagonist, rather like real-life pythons and boas. They could even survive being chopped into several pieces, because the pieces swiftly reconnected with one another unless they were buried separately or burnt immediately.

Perhaps the most famous British worm is the Lambton worm, which reputedly grew from a small black leech-like beast caught in the River Wear, County Durham, on Easter Sunday 1420 by John Lambton - the youthful, impious heir to Lambton Castle, who had gone fishing while everyone else from the town of Washington close by attended church. Cursed for his blasphemy, Lambton sought redemption by journeying to the Holy Land on a pilgrimage after hurling his loathsome-looking catch into a nearby well. When he returned several years later, however, he was horrified to discover that the creature had grown into a monstrous worm that had been terrorising Washington's inhabitants by devouring their lifestock, wilting their crops with its toxic breath, and killing anyone who had dared to challenge it. Even chopping it in two had been futile – the two halves simply rejoined straight away.

Happily, however, Lambton was able to rid the town of this accursed creature. After seeking the advice of a wise witch, he commissioned the creation of an extraordinary suit of armour, bristling with long sharp spines. He then enticed the worm into the River Wear, and as soon as it attempted to crush him in its mighty coils, the spines on his armour sliced it into several segments, which were immediately carried away and dispersed by the river's fast-flowing current, so that they were unable to reconnect. Thus ended the Lambton worm's reign of terror.

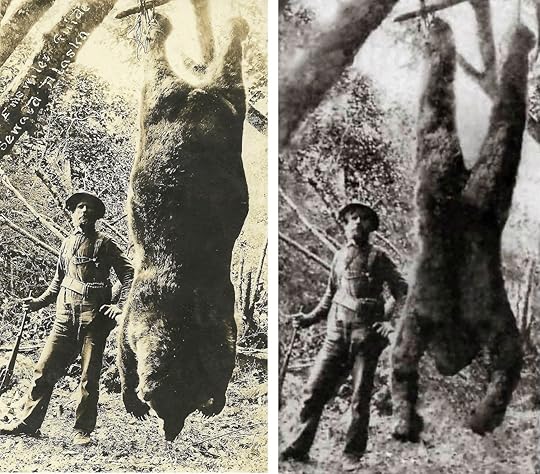

The Lambton worm, from an 1894 book of fairy tales (public domain)

The Lambton worm, from an 1894 book of fairy tales (public domain)This famous myth has been preserved through generations of retellings in northern England, but how it originated remains a mystery - unless, perhaps, the worm was in reality some less dramatic wild beast (or even an imaginative personification of a local now-forgotten natural disaster) that John Lambton had successfully combated? Having said that, however, eminent English historian and antiquarian Robert Surtees (1779-1834) claimed that during the early 19th Century he had seen at the village of Lambton (aka Old Lambton) in Washington a piece of preserved skin said to be from the Lambton worm, and which resembled the hide of a bull.

A similar ploy to Lambton's wearing of a spiny suit of armour was utilised in the killing of another British worm. This was when, during the 1300s, Sir William Wyvill wore a suit of armour covered in razor-sharp blades when battling an enormous worm at Slingsby in North Yorkshire. But this time, instead of a river dispersing the worm's body segments, the knight's faithful dog carried each segment away and buried it in a different location. Despite its resourcefulness, however, it could not save its master, or itself, from the worm's baneful effects. When it licked its grateful master's face, drops of the worm's deadly blood upon its jaws transferred inside its mouth and also onto the knight's face, and both man and dog died shortly afterwards.

THE HYDRA OF HERACLES AND THE HOAXED HYDRA OF HAMBURG

One of the most unusual, and deadly, dragons, of classical mythology was the Lernean hydra - whose slaying constituted one of the twelve great labours of the Greek hero Heracles (Hercules in Roman mythology).

Although this monster is usually depicted as wingless and only two-legged, it was more than ably compensated by virtue of its numerous heads (generally given as nine, but sometimes only seven, or as many as thirteen), each borne upon a separate neck. And each time that a head was cut off, two new ones grew in its stead, until Heracles successfully countered this by burning each neck as soon as its head was lopped off.

Produced in 1921, John Singer Sargent's sumptuous rendition of Heracles battling a mighty 13-headed hydra (public domain)

Produced in 1921, John Singer Sargent's sumptuous rendition of Heracles battling a mighty 13-headed hydra (public domain)Even more marvellous in its own deceiving manner was the hoaxed hydra that was removed from a church in Prague in 1648 and subsequently owned by Johann Anderson, the Burgomaster of Hamburg. So spectacular was this preserved wonder that Anderson even rejected an offer of 30,000 thalers for it from Frederick IV, king of Denmark. In basic form, the hydra resembled a standard lindorm, sporting a long tail and sturdy scaled body but only two limbs and no wings. Instead of just a single neck and head, however, it boasted no less than seven of each, with all of the necks emerging from a common base.

Yet despite the hydra's extraordinary appearance, its perceived monetary value eventually decreased, until by 1735 negotiations had begun for its sale at a mere 2000 thalers. Before these could be completed, however, eminent naturalist Carl Linné (who subsequently Latinised his name to Linnaeus) examined this celebrated specimen, and exposed it as a fraud. The heads, jaws, and feet were those of weasels, and a series of snake skins had been pasted all over its body.

Depiction of the hoaxed hydra of Hamburgin Albertus Seba's Cabinet of Natural Curiosities (Vol. 1), 1734 (public domain)

Depiction of the hoaxed hydra of Hamburgin Albertus Seba's Cabinet of Natural Curiosities (Vol. 1), 1734 (public domain)Linnaeus speculated, however, that this exhibit had probably been created not by wily vendors to sell as a supposedly genuine hydra to some unwary buyer for an eye-watering sum of money, but rather by monks as a representation of the seven-headed dragon of the Apocalypse with which to chastise and terrify disbelievers. Yet whatever the reason, the result was outstanding, but even so, once this hoaxed hydra's true nature had been revealed by Linnaeus, the deal for its sale fell through, and shortly afterwards the hydra itself vanished – never to be seen again.

DRAGONS ON CHILDREN'S TELEVISION

There have been many notable small-screen dragons, but thanks to the charmed tenacity of nostalgia, perhaps those that we most readily recall are ones that featured in shows from our childhood.

One of the legendary names in British children's TV is Oliver Postgate (1925-2008), who created and wrote some of the most beloved shows of all time in this special genre of television – 'Bagpuss', 'Clangers', 'Noggin the Nog', 'Ivor the Engine', and 'Pogles' Wood', among others. They were all made by his company Smallfilms (founded with Peter Firman), and screened by the BBC. Some of these featured delightful dragons, remaining cherished childhood memories for generations.

Originally screened from 1969 to 1972 but repeated numerous times thereafter, 'Clangers' was a stop-motion show of 27 10-minute episodes. They featured a family of small whistling aliens, the clangers, with long snouts and knitted waistcoats. These share a tiny hollow planet with a host of exotic fauna and flora, such as the iron chicken, the froglets, the musical trees, and, most notable of all, the soup dragon. It is she who obtains from the planet's volcanic soup wells the delicious blue string pudding and green soup that the clangers adore. It was this character (and her baby dragon) who inspired the name of Scottish alternative rock band The Soup Dragons.

A delightful personal interpretation by fantasy artist Anthony Wallis of the soup dragon from 'Clangers' (© Anthony Wallis)

A delightful personal interpretation by fantasy artist Anthony Wallis of the soup dragon from 'Clangers' (© Anthony Wallis)Consisting of 27 10-minute episodes (six in colour) of limited stop-motion photography and first screened in 1959, 'Noggin the Nog' was a Norse-type saga about a tribe of Northmen, the Nogs, led by King Noggin, and featuring an extensive cast of characters. These include Noggin's villainous uncle Nogbad the Bad, inventor Olaf the Lofty, a giant green bird called Graculus, Arup the great walrus, and an amiable ice dragon known as Groliffe (not to mention a flying machine and a fire machine!). Befriended by Noggin, Groliffe subsequently comes to his aid when he and his friends are in trouble.

Spanning 1959 to 1977 and consisting of 32 10-minute black-and-white episodes and 40 5-minute colour episodes of stop-motion photography, 'Ivor the Engine' was famously set in "the top left-hand corner of Wales". It features a green locomotive called Ivor, his driver (Edwin) Jones the Steam, plus several supporting characters. Notable among them is Idris, a small red heraldic dragon based upon the emblem of Wales, who lives with his wife and two dragon children in an extinct volcano called Smoke Hill, and sings in the local choir.

A dragon called Dennis who combined the best of both geographical types appeared in 'James the Cat' – a cartoon series of 52 5-minute episodes screened by the BBC from 1984 to 1992. One of many animal friends of the show's title character, Dennis is a pink Chinese dragon but breathes fire and speaks with a Welsh accent!

A happiness-bringing luck dragon long before Falkor debuted in the novel and film versions of The Neverending Story, Chorlton was the friendly but somewhat slow-witted star of an enchanting British series entitled 'Chorlton and the Wheelies', originally screened on ITV from 1976 to 1979. In the very first of its 40 stop-motion animated episodes, created by the company Cosgrove Hall, Chorlton hatches from an egg and then arrives in Wheelie World. This is a strange land populated mostly by Wheelies – creatures that have wheels instead of legs, but which are burdened with sadness conjured up by a wicked witch called Fenella...until Chorlton's happiness soon dispels the gloom. In subsequent episodes, Fenella puts into practice all manner of evil schemes to rid Wheelie World of Chorlton, or cause problems for him, but he and his Wheelie friends invariably manage to foil them.

One of the most popular series from the golden age of children's TV in the USA was 'H.R. Pufnstuf', a live-action show featuring life-sized puppets whose 17 25-minute episodes were first screened from September 1969 to September 1971. H.R. Pufnstuf is not only a dragon but also a mayor – of a magical isle called Living Island. Here everything is alive, even the houses, and is where an 11-year-old boy called Jimmy (played by Jack Wilde, the artful dodger in the 1968 film musical Oliver!) and his talking flute Freddy are taken to in a mysterious boat. The series' basic scenario is similar to that of 'Chorlton and the Wheelies', in that the bane of Living Island is a troublesome witch, called Witchiepoo here, but her evil plans are always thwarted by the dragon, Jimmy, and their many friends there.

Originally aired in Canada and the USA from 1993 to 1997, and running to five seasons, collectively containing 65 30-minute episodes, 'The Adventures of Dudley the Dragon' was a live-action show in which a full-costumed actor played Dudley. Befriended by two children after waking up from centuries of hibernation, Dudley finds out what the modern-day world is like, with particular emphasis upon environmental issues.

Other popular children's TV shows featuring dragons included 'Wacky Races', 'My Little Pony', 'The Smurfs', 'Pocket Dragon Adventures', 'Eureeka's Castle', 'Digimon', and, for older children and teenagers, 'Power Rangers', 'Dungeons and Dragons', and several Manga series. Moreover, countless TV cartoons have featured dragons as one-off foes or comic relief characters.

Not all dragons are huge and frightening, some are very small and very sweet, especially in children's media (© Thomas Finley)

Not all dragons are huge and frightening, some are very small and very sweet, especially in children's media (© Thomas Finley)THE PELUDA – SHAGGY SURVIVOR OF NOAH'S GREAT FLOOD

Even among the unparalleled diversity of dragon forms, the following example from traditional French folklore was truly unique and unforgettable.

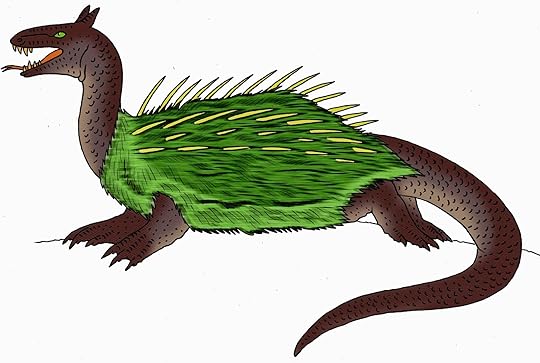

There on the bank of the river Huisne, at La Fert‚-Bernard in medieval France, something was definitely moving. Suddenly, what appeared at first to be the head and sinuous body of a huge viper-like snake emerged from a spherical mass of bright green vegetation, and reared upwards above it. Moments later, however, the vegetation itself began to move, quivering as if it were a living creature - which was only to be expected, for that was precisely what it was. What had seemed to be nothing more than a cluster of riverside foliage was in reality the round body of a huge animal with shaggy green fur - and what had appeared to be a giant serpent was now exposed as this extraordinary animal's head and neck!

It was the peluda - a terrifying amphibious neo-dragon also known as the shaggy beast, which had been spawned in early biblical days and was refused entry onto Noah's Ark, yet had nonetheless survived the Great Flood, and was now terrorising the environs of La Fert‚-Bernard. Its dense green pelage partially hid four horny, turtle-like feet, and bristled with countless numbers of spine-like quills - which contained potent stinging venom, and could be jettisoned like poisonous javelins into anything unwary enough to approach too closely. This monstrous beast could also kill a person with a mighty thwack of its immensely powerful tail - and when it was sufficiently angered, a single blast of flame spewed forth from its coiled throat could incinerate fields for miles around.

The peluda or shaggy beast (© Helena Zakrzewska-Rucinska/Dr Karl Shuker/MarshallEditions, from my book

Dragons: A Natural History

)

The peluda or shaggy beast (© Helena Zakrzewska-Rucinska/Dr Karl Shuker/MarshallEditions, from my book

Dragons: A Natural History

)For a time, the peluda had contented itself with raiding farms and stables each night in search of horses and other livestock as prey - robbing the farmers of their livelihood, but rarely of their lives, unless they were foolish enough to challenge its depredations.

Occasionally, massed attacks on the beast by brave companies drawn from the local populace had succeeded in driving it into the Huisne - but the peluda was of such colossal size that whenever it submerged itself underwater, the river immediately overflowed its banks, and much of the district bordering on either side was completely flooded, thereby causing as much devastation to the farmers as the monster's own onslaughts.

More recently, however, the situation had become even worse, for the peluda had lately expanded its dietary scope - adding children and damsels to its murderous menu. Several of the village's fairest maidens had been devoured, and only this morning yet another had been ambushed and carried away - but this time she had not been alone. Her valiant fianc‚ had been nearby, and had witnessed the terrible deed. Now he swore vengeance against her antediluvian attacker, and he took up his trusty sword to do battle.

Protected from the peluda's deadly arsenal of self-propelling quills by his suit of mail, and additionally armed with knowledge gained from the village's wisest seer, the bold youth strode forth and aimed a terrible blow with his sword - but not at the monster's undulating neck, and not even at the heaving belly concealed beneath its shaggy fur. Instead, he hacked down at its writhing tail, and severed it in two with a single slash of his keen blade. Instantly, the mighty peluda keeled over and died - for its tail was the only portion of its body vulnerable to mortal injury.

Back in La Fert‚-Bernard there was great rejoicing, and the remains of the peluda were embalmed. As for its conqueror, he was acclaimed forever more as a hero, and rightly so - after all, he had achieved a feat that not even the Great Flood had been able to accomplish!

Another artistic representation of the peluda (© Tim Morris)

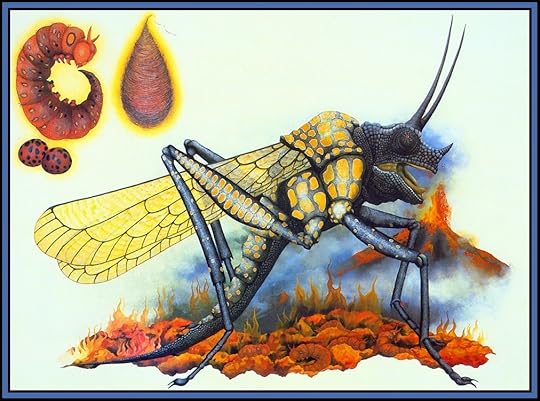

Another artistic representation of the peluda (© Tim Morris)THE PYRALLIS – A VERITABLE FIRE-FLY DRAGON!

The smallest of all dragons and entirely at home in the midst of a blazing fire was a tiny beast termed the pyrallis. Also called the pyragones or pyrausta, this remarkable animal was no bigger than a large fly, and resembled a four-legged insect, with burnished bronze body and golden filigree wings - but its head was that of a dragon.

A pyrallis, as depicted by Una Woodroffe in her spectacular illustrated book Inventorum Natura (© Una Woodroffe/Paper Tiger)

A pyrallis, as depicted by Una Woodroffe in her spectacular illustrated book Inventorum Natura (© Una Woodroffe/Paper Tiger)It was associated exclusively with the copper smelting forges and foundries of Cyprus, in which swarms would dance and cavort like incandescent will-o'-the-wisps. Yet if one of these animate sparks should fly out of the flames, even for the briefest of instants, it would die at once - because the pyrallis drew not merely its sustenance but its very life-force from the furnaces' burning heat and raging vitality. Truly a beast of the fire and the flame!

DRAGONS OF MIDDLE-EARTH

Considered by many readers and literary critics alike as the most significant and influential modern-day works of fantasy fiction ever published, The Hobbit (1937), The Lord of the Rings trilogy (1954, 1954, 1955), The Silmarillion (1977), and J.R.R. Tolkien's other novels contain a number of important dragons.

It has often been supposed that his works are Christian allegories or are at least derived from Christian themes, and therefore comparable in terms of inspiration to the Narnia novels of C.S. Lewis. In reality, however, Tolkien's principal muse was the Elder Edda – a collection of Old Norse myths and legends preserved principally within the Codex Regius, which is a medieval Icelandic manuscript, written in the 13th Century. Yet the myths and legends themselves are far older, and include all of the famous Norse ones known today.

Many familiar character names in Tolkien's books, for example, including Gandalf and various of the dwarves featuring in The Hobbit, were borrowed directly by him from the Elder Edda. So too were other entities and themes, one of which that attracted his particular attention being the slaying by the hero Siegfried of the evil dwarf Fafnir, who had transformed himself into a typical Nordic dragon in order to protect his ill-gotten treasure hoard. This dragon became the basic template for the various examples featuring in Tolkien's novels.

Siegfried slaying a dragon-transformed Fafnir in this stunning artwork by Arthur Rackham (public domain)

Siegfried slaying a dragon-transformed Fafnir in this stunning artwork by Arthur Rackham (public domain)Yet although Tolkien's dragons were of traditional Nordic form and treasure-hoarding behaviour, they were much more intelligent than their antecedents in the Old Norse myths and legends, and they could speak too.

Created by the dark lord Morgoth, there were three types – the great worms, the winged quadrupedal dragons, and the wingless quadrupedal dragons. Some could also breathe fire, enabling them to destroy the lands and cities of Middle-Earth's men, elves, and dwarves.

The first Middle-Earth dragon was Glaurung, a huge wingless fire-breather, which ultimately spawned numerous lesser dragons, and led them into battle on the side of Morgoth against the elves, but was finally slain by the hero-warrior Túrin.

The greatest Middle-Earth dragon of all, however, was Ancalagon the Black, the first winged fire-breather. His appearance alongside his spawn astonished the entire world, and initially gave victory to Morgoth's horde – until the great eagles and other warrior birds rallied against them, eventually achieving victory over their reptilian foes and breaking Morgoth's power forever. Ancalagon was slain by warrior Eärendil, and so enormous was this mighty dragon's body that when it plummeted down from the sky to earth, it decimated the three-peaked mountain Thangorodrim.

The last famous Middle-Earth dragon was Smaug, a huge golden-red winged monster almost entirely ensheathed in impermeable iron scales. Smaug destroyed with fire the human city of Dale and vanquished the dwarves from the Kingdom under the Mountain (of Erebor) in order to seize for himself their vast treasure of gold, jewels, and precious elvish metals stored there. This he jealously guarded for almost two centuries until disturbed by a party of dwarves seeking retribution, led by Thorin Oakenshield and also including among their number the hobbit Bilbo Baggins. It was Bilbo who discovered the one vulnerable region on Smaug's underside, which enabled a Northman archer named Bard the Bowman to slay Smaug after he had attacked the city of Esgaroth upon the Long Lake.

More light-hearted and whimsical was another Tolkien dragon – Chrysophylax Dives. Pompously comical but still wily and villainous, he was finally captured and controlled by Farmer Giles of Ham in the book of the same title, using a mighty sword called Caudimordax (aka Tailbiter) that once belonged to a famous dragon-slayer.

A classic collection of Tolkien characters (© Richard Svensson)

A classic collection of Tolkien characters (© Richard Svensson)THE LONGMA – SCALY DRAGON HORSE OF CHINA

One of the most unusual Oriental dragons was the longma or Chinese dragon horse. Traditionally deemed to be the vital spirit of Heaven and Earth, as indicated by its English name it was a curious yet surprisingly effective composite of two very different animals - sporting the body, legs, and hooves of a horse, but the head and scales of a dragon. Some, though not all, dragon horses also possessed a pair of wings, and could walk upon the surface of water without sinking.

Legend has it that eight winged dragon horses pulled the carriage of Emperor Mu of Jin (belonging to the Eastern Jin Dynasty) as he travelled around the world during the post-regency period of his reign (he reigned from 343 AD to 361 AD).

It was a yellow dragon horse that emerged long ago from the River Lo to reveal the eight trigrams of the famous divination system known as I Ching. Similarly, a dragon horse rose up out of the Yellow River and gave to the Emperor a circular diagram depicting the yin-yang.

Wooden carving of a dragon horse (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Wooden carving of a dragon horse (© Dr Karl Shuker)According to the Imperial Readings of the Taiping Era (aka Taiping Yulan) – a massive 1000-volume, multi-contributor Chinese encyclopaedia dating from the 10thCentury – a dragon horse spotted blue and red, covered in scales, sporting a thick mane, and giving voice to a mellifluous flute-like neigh once appeared in the year 741 AD, which was taken to be a good omen for the reigning emperor, Xuanzong of Tang. So fleet-footed that it could cover more than 280 miles without a pause, this wonderful beast had been born to a normal mare that had become pregnant after drinking water from a river in which a dragon had bathed.

During the 7thCentury, the Turkestan city of Kucha (now part of China) was visited by the travelling Chinese Buddhist monk and scholar Hsuan-Tsang, who noticed that a lake in front of one of this city's temples contained a number of water dragons. He was informed that they could change their form so as to mate with mares, and that the progeny of this curious crossbreeding were dragon horses, of a fierce, wild nature, and very difficult to tame.

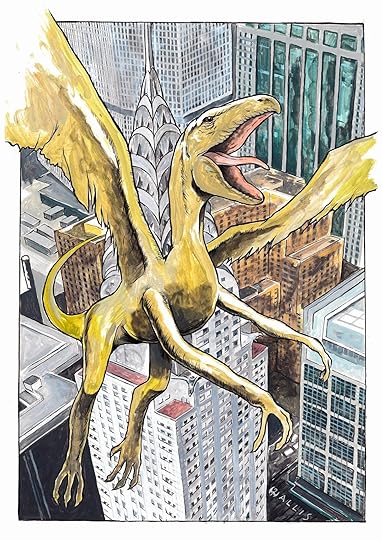

Q – A VERY QUIRKY MOVIE DRAGON

One of the quirkiest yet most original dragon-based films ever released, and one of my own particular favourites, is director Larry Cohen's 'Q – The Winged Serpent' (1982). In it, a cult in New York City successfully resurrect Quetzalcoatl, the ancient flying serpent deity of Aztec mythology, who proceeds to swoop down from Manhattan's skies and skyscrapers to seize, dismember, and devour unwary city dwellers.

In appearance, however, this odd-looking entity is not serpentine at all, instead resembling a rather gangly, long-necked quadrupedal dragon with wings. Yet its smooth skin seems devoid of typical reptilian scales or spines, and it does not sport any feathers either – despite the original Quetzalcoatl being a plumed sky serpent.

Fantasy artist Anthony Wallis's superb personal interpretation of Q – the Winged Serpent (© Anthony Wallis)

Fantasy artist Anthony Wallis's superb personal interpretation of Q – the Winged Serpent (© Anthony Wallis)Perhaps the epitome of the modern-day dragon film, however, is 'Reign of Fire' (2002), directed by Rob Bowman, and starring Christian Bale and Matthew McConaughey.

Set in the year 2020, this post-apocalyptic film reveals the devastation that has resulted after a sleeping dragon was inadvertently chanced upon and woken in an underground cave during some construction work on the London Underground shortly after the beginning of the new millennium. The dragon forced its way to the surface, swiftly multiplied, and within a dozen years humanity was virtually wiped out by a worldwide plague of flying fire-breathing dragons.

Finally, however, a brave survivor, Quinn Abercromby (played by Bale), and his isolated community hiding out in a Northumberland castle reluctantly join forces with a band of American fighters led by Denton Van Zan (McConaughey) to bring to a decisive end the dragons' literal reign of fire. Although the story's premise seemed decidedly far-fetched, the special effects were truly astonishing.

A memorable 'Reign of Fire' dragon as personally interpreted by fantasy artist Anthony Wallis (© Anthony Wallis)

A memorable 'Reign of Fire' dragon as personally interpreted by fantasy artist Anthony Wallis (© Anthony Wallis)A COLLECTION OF PRESERVED 'CROCODILE DRAGONS'

There are a number of so-called 'preserved dragons' in existence around the world, but when examined some of these physical specimens have been readily exposed as being of crocodilian identity. Perhaps the most notable example is the 'Brno lindworm' (wingless four-legged classical dragon), of Moravia in the Czech Republic, which since at least 1608 AD has been hanging suspended from the ceiling of the arched passage leading to the city's town hall, and can still be seen here today. To protect it from the weather, it has been liberally covered in black pitch, but its identity as a crocodile – albeit a very sizeable one, as it measures approximately 15.5 ft long - remains instantly apparent.

The preserved Brno'lindworm' dragon (© Miroslav Fišmeister)

The preserved Brno'lindworm' dragon (© Miroslav Fišmeister)According to traditional Moravian folklore, this is the dragon that long ago was said to have slaughtered livestock and even young children in a prolonged assault on Brno (then called Brünn), until it was duped into feeding upon a freshly-killed calf's skin that had been cunningly filled with unslaked lime. After eating it, the dragon was consumed with such a fiery thirst that it drank without pause from a nearby stream until finally the lime reacting with the vast quantity of imbibed water caused the doomed dragon to explode.

The same fate befell Smok, the dragon of Wawel Hill in Krakow, Poland, which had terrorised the city until Skuba, a canny cobbler's apprentice, stuffed a baited lamb with sulphur. Incidentally, in 2011 a very large species of Polish carnivorous reptile from the late Triassic Period 205-200 million years that may constitute a species of theropod dinosaur was officially christened Smok wawelski, in honour of this Polish dragon.

Souvenir ornament portraying Smok (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Another crocodilian dragon once hung from the roof of the cathedral of Abbeville in Picardy, France. And until at least as recently as the early 1850s, what was either a stuffed 6-ft-long crocodile or lizard (monitor?) could be seen suspended in the church of St Maria delle Grazie, near Mantua, in Italy. Local lore claims that it had been killed in some adjacent swamps in c.1406. More likely is that all of these specimens had been brought back to Europe as unusual souvenirs by returning travellers or crusaders, or even as exotic living specimens for private collections or sideshows.

DRAGON TATTOOS

Body art has experienced an enormous resurgence in recent years, especially tattoos and tattooing, and one of the most fashionable, in-demand subjects for a tattoo is the dragon. Indeed, there is even a much-sought-after book devoted entirely to dragon tattoos – Donald Ed Hardy's lavishly-illustrated tome Dragon Tattoo Design (1988), containing countless designs for every taste in dragons.

Whether in the West or the East, most tattooed dragons are of the Oriental category (though the red Welsh dragon is popular as a symbol of Celtic patriotism). Its slender, serpentine form and rich spectrum of vivid colours allows itself to be readily applied to a person's back, arms, chest, or legs, and to achieve individuality for them. Several notable celebrities sport dragon tattoos, including singers Lenny Kravitz, Pink, and Mels B and C of the Spice Girls, as well as actor Bruce Willis, and actress Angelina Jolie.

There is a plethora of symbolism associated with dragon tattoos, depending in particular upon their type, colour, activity, the presence of other animals alongside them, and the sex of the person selecting them.

Oriental dragons in general are associated with freedom, protection, and nobility, but in keeping with their status and role in traditional mythology, the tattoo of a Chinese dragon more specifically symbolises good fortune and wisdom, whereas the more elongate, fewer-clawed Japanese dragon personifies balance in life. As already noted, the Celtic dragon symbolises pride in one's Celtic ancestry but also power and strength, and is sometimes depicted alongside a crown or even a throne. Other Western dragons, which are particularly popular when portrayed as stylised tribal tattoos, also represent bravery, ferocity, and even war-like attributes - hearkening back to their traditionally darker, less benign image than that of their Oriental counterparts.

A Western dragon in a tribal tattoo design (public domain)

A Western dragon in a tribal tattoo design (public domain)A tattoo of a yellow Oriental dragon symbolises knowledge, helpfulness, and a good companion, as does one of a gold Oriental dragon (which is also utilised to indicate a kind personality), whereas a green one embodies life and the planet, a red one symbolises keen eyesight, and a black one shows that its bearer has old but wise parents. A blue dragon tattoo is associated with compassion and forgiveness. But beware: in Chinese tradition, blue dragons also symbolise sloth and idleness - so make sure that you don’t give out the wrong impression if you choose this symbol as a tattoo!

A tattoo depicting an Oriental dragon protecting treasure signifies wealth (either material or spiritual). A coiled dragon personifies the oceans but also suggests that, just like those vast bodies of water, the person bearing this tattoo has hidden, mysterious depths to their personality, and a horned dragon represents strength and authority in both deed and intent, because only the more advanced Oriental dragons possess horns. If the fuku-riu type of Japanese dragon is chosen for a tattoo, its bearer is hoping to attract good fortune, as this type is traditionally the luck dragon in Japan.

Oriental dragons are still revered as rain and water deities, so if such a dragon is tattooed reposing near to water, i.e. its normal resting state, this symbolises tranquillity and peace of mind. However, if the dragon's teeth show, or, if winged, its wings are extended, this can denote hostility or aggression. Taking great care and giving thought beforehand when selecting a dragon tattoo is very important, therefore, to avoid its sending out an inappropriate or unwanted message, especially as tattoos cannot be easily removed or amended once applied.

My own tattoo of a serpent dragon entwined around a dagger, symbolising strength, which was tattooed on me by Birmingham-based tattoo artist and good friend Gary Stanley, aka Stigmata (© Dr Karl Shuker)

My own tattoo of a serpent dragon entwined around a dagger, symbolising strength, which was tattooed on me by Birmingham-based tattoo artist and good friend Gary Stanley, aka Stigmata (© Dr Karl Shuker)Dragon tattoos on men typify the general dragon-allied symbolism of power, wisdom, courage, and protection, and are often applied to readily-visible regions of the body like arms or legs (often as full-sleeve tattoos), across the shoulders or chest, or encompassing the back. When present on women, conversely, they tend to appear on less overt regions, such as feet, ankles, nape, near the navel, or down the sides, and are more closely linked with creation, emphasising that it is women who give birth. Consequently, mothers (especially new ones) often select a dragon when choosing a tattoo.

Sometimes an Oriental dragon and Chinese phoenix are tattooed together, forming a circle or otherwise intimately linked with one another, which symbolises a successful marriage. Tigers in ancient Oriental tradition often represent aggression and evil intent, so a dragon tattooed above a tiger indicates that its bearer has overcome darkness in their life, or intends always to do so. Avoid tattoos of dragons battling with tigers if tattoo symbolism is important to you, however, because these images can indicate aggression or internal conflict.

An attractive way of enhancing both the physical appearance and the symbolic significance of a dragon tattoo is to add a message alongside it, written in either Chinese Hanji or Japanese Kanji script.

Above all, a dragon tattoo signifies that the bearer is special. If there could be just a single tattoo to personify the phrase "Why be ordinary when you can be extraordinary?", it would be a dragon.

The continuing popularity of dragons in every conceivable facet of our culture confirms that even though we may no longer believe in them, we certainly cannot forget them! Indeed, it is evident that the dragon will continue to evolve, diversify, and populate our planet for a very long time to come. The dragon is dead - long live the dragon!

And here's one I slew earlier! (© Dr Karl Shuker)

And here's one I slew earlier! (© Dr Karl Shuker)This ShukerNature article is excerpted from my books Dragons: A Natural History and Dragons in Zoology, Cryptozoology, and Culture – check them both out for vast amounts of addition dracontological data!

Published on April 03, 2015 17:13

April 1, 2015

'IF ONLY...' - IN MEMORY OF MY MOTHER, MARY SHUKER (1921-2013)

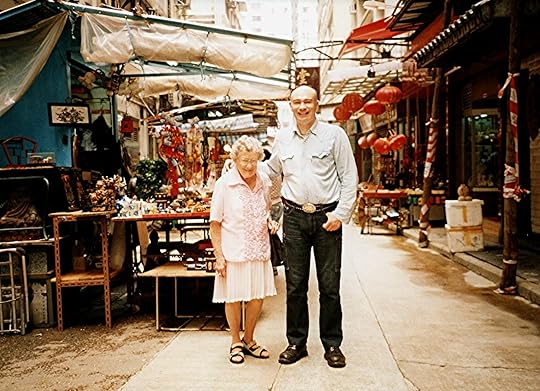

(Above and below) Mom and I at Hong Kong's Cat Street Markets/Galleries, summer 2005 (© Dr Karl Shuker)

(Above and below) Mom and I at Hong Kong's Cat Street Markets/Galleries, summer 2005 (© Dr Karl Shuker)Please click: Star Steeds and Other Dreams: IF ONLY...

Published on April 01, 2015 16:38

March 18, 2015

BOTHERSOME BEITHIRS AND OTHER FRESHWATER MYSTERY EELS?

Delightful depiction of Nessie as a giant eel (© Richard Pullen)

Delightful depiction of Nessie as a giant eel (© Richard Pullen)I have already discussed on ShukerNature the prospect that certain serpentiform sea monsters might be still-undiscovered giant marine eels – Dr Bernard Heuvelmans's 'super-eel' category of sea serpent (click here ). Similarly, a number of freshwater mystery beasts reported from Britain and elsewhere in the world may also conceivably be unusually large eels - a thought-provoking possibility previously visited on ShukerNature in relation to reports from ancient times of supposed giant blue eels inhabiting India's Ganges River (click here ), and now revisited in the following selection of additional eye-opening examples.

NEVER BOTH A BEITHIR

The Loch Ness monster (LNM) may well be Scotland's best known freshwater mystery beast, but it is not this country's only one. Far less familiar yet no less intriguing in its own way is the beithir. In 1994, a correspondent to the English magazine Athenepublished two fascinating articles containing various modern-day beithir sightings. During early 1975, he encountered a fisherman near Inverness who claimed that he and four others once sighted a beithir lying coiled in shallow water close to the edge of a deep gorge upstream of the Falls of Kilmorack. When it realised that it had been observed, however, it thrashed wildly about before finally swimming up the gorge near Beaufort Castle and disappearing. The fishermen estimated its length at around 10 ft.

Four months later, the Athene correspondent learnt of another sighting, this time offshore of Eilean Aigas, an island in the River Beauly, Highland. He was also informed by a keeper at Strathmore that during the 1930s his wife's parents had seen beithirs moving overland at Loch a' Mhuillidh, near Glen Strathfarrar and the mountain of Sgurr na Lapaich. After discussing these reports with various zoological colleagues, he considered that the beithir was probably an extra-large variety of eel – fishes that are well known for their ability to leave the water and move overland to forage when circumstances necessitate, and even to sustain themselves out of water for protracted periods.

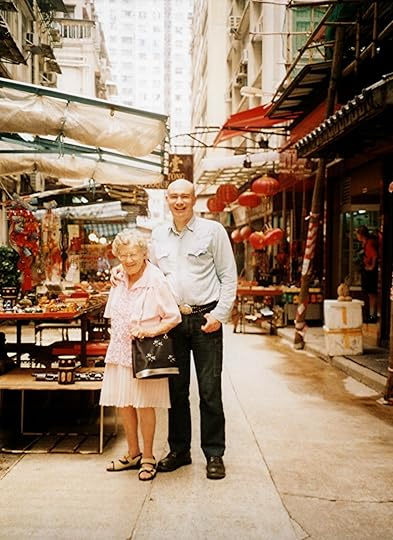

The European eel, painting from 1837 (public domain)

The European eel, painting from 1837 (public domain)Indeed, the Athene correspondent was informed by a Devon farmer that during the extremely harsh winter of 1947, his mother had been badly frightened to discover a number of eels alive and well in the farm's hayloft, where they had evidently been sheltering since the freezing over of the nearby river some time earlier. The rest of the family came to see this wonder, including the farmer himself (then still a boy), and his father confirmed that they were indeed eels, and not snakes (as his mother had initially assumed).

IS NESSIE A EUNUCH EEL?

The LNM (always assuming that it actually exists, of course!) has been labelled as many things by many people – a surviving plesiosaur, an unknown species of long-necked seal, and a wayward sturgeon being among the most popular identities proffered over the years. However, some eyewitnesses and zoological authorities – notably the late Dr Maurice Burton – have favoured a giant eel, possibly up to 30 ft long.

Under normal circumstances, the common or European eel Anguilla anguilladoes not exceed 5 ft, and even the conger eel Conger conger (one of the world's largest eel species, rivalled only by certain moray eels) rarely exceeds 10 ft. However, ichthyological researchers have revealed that growth in eels is more rapid in confined bodies of water (such as a loch), in water that is not subjected to seasonal temperature changes (a condition met with in the deeper portions of a deep lake, like Loch Ness), and is not uniform (some specimens grow much faster than others belonging to the same species).

Collectively, therefore, these factors support the possibility that abnormally large eels do indeed exist in Loch Ness. Moreover, sightings of such fishes have been claimed by divers here. Also of significance is the fact that eels will sometimes swim on their side at or near the water surface, yielding the familiar humped profile described by Nessie eyewitnesses. And a 18-30-ft-long eel could certainly produce the sizeable wakes and other water disturbances often reported for this most famous – and infamous – of all aquatic monsters.

The conger eel (public domain)

The conger eel (public domain)Consequently, I would not be at all surprised if the presence of extra-large eels in Loch Ness is conclusively demonstrated one day. However, I cannot reconcile any kind of eel with the oft-reported vertical head-and-neck (aka 'periscope') category of LNM sightings, nor with the land LNM sightings that have described a clearly-visible four-limbed, long-necked, long-tailed animal.

Yet regardless of what creature these latter observations feature (assuming once again their validity), there is no reason why Loch Ness should not contain some extra-large eels too. After all, any loch that can boast a volume of roughly 1.8 cubic miles must surely have sufficient room for more than one type of monster!

In recent years, the giant eel identity for Nessie has been modified by some cryptozoological researchers to yield a creature as remarkable in itself as any bona fide monster – namely, a giant eunuch eel. It has been suggested that Nessie may be a gigantic, sterile or eunuch specimen of the common eel – one that did not swim out to sea and spawn but instead stayed in the loch, grew exceptionally long (25-30 ft), lived to a much greater age than normal, and was rendered sterile by some currently-undetermined factor present in this and other deep, cold, northern lakes.

This is undeniably a fascinating, thought-provoking theory, but Dr Scott McNaught, Professor of Lake Biology at Central Michigan University, has stated that even if such eels did arise, they would tend to grow thicker rather than longer. Nevertheless, giant eels remain a distinct possibility in relation to some of the world’s more serpentiform lake monsters on record.

MONSTER EELS IN THE MASCARENES

The concept of giant freshwater eels is by no means limited to Britain. For example: a number of deep pools in the Mascarene island of Réunion, near Mauritius, in the Indian Ocean, are supposedly inhabited by gigantic landlocked eels.

In a letter to The Field magazine, published on 10 February 1934, Courtenay Bennett recalled seeing during the 1890s when Consul at Réunion a dead specimen that had been caught in one such pool, the Mare à Poule d'Eaux, which is said to be very deep in places. It was so immense that "steaks as thick as a man's thighs were cut" from its flesh.

Mare à Poule d'Eaux (©

http://www.chat-reunion.com

)

Mare à Poule d'Eaux (©

http://www.chat-reunion.com

)According to native testimony, moreover, during the heavy winter rains the giant eels could apparently be seen circling along the sides of this lake, searching for a way out. Being so exposed, however, they were prime targets for local hunters, who would catch them using a harpoon and a rope hitched round a tree. Their flesh would then be sold for food in a neighbouring village.

EXTRA-LARGE EELS IN JAPAN?

Several of Japan's biggest lakes are associated with accounts of freshwater eels reputedly much larger than typical specimens on record from these localities. A concise coverage of such creatures appeared in a detailed article concerning Japanese giant mystery fishes that was written by Brent Swancer and posted on 30 April 2014 to the Mysterious Universe website (click here to access the full article) and reads as follows:

Various locations in Japan have had reports of huge eels far larger than any known native species.

Workers doing construction on a floodgate on the Edo river reported coming across enormous eels measuring 2 meters (6.6 feet) long. According to the account, four of the eels were spotted and some of the workers even attempted to capture one, as the eels appeared to be rather lethargic and slow moving. They were unsuccessful as they did not have the equipment to properly catch one. Upon returning to the scene later on with the tools they needed, they found that the mysterious giant eels were nowhere to be seen.

Another account comes from Lake Biwa, which is in Shiga Prefecture, and is the largest freshwater lake in Japan. In the 1980s, there were several reports of giant eels inhabiting the lake.

One such sighting was made by a large group of people aboard one of the lakes many pleasure boats. Startled ferry passengers reported seeing several very large eels swimming at the surface far from shore. The eels were described as being around 3 meters (around 10 feet) long, and a silvery blue color. The eels appeared to be leisurely gliding along beside the boat and were observed for around 15 minutes before moving off out of sight.

A fisherman on the same lake reported actually hooking and reeling in an eel that was reported to be around 8 feet in length. In this case, the eel was kept and eaten. Another fisherman on the lake reported seeing a similarly sized eel rooting through mud in shallow water near the shore.

Japan's Lake Biwa, as seen from Higashiamagoidake (public domain)

Japan's Lake Biwa, as seen from Higashiamagoidake (public domain)Interestingly, the giant blue eels of Lake Biwa readily recall comparably-described mystery beasts from India's Ganges River as reported by several early chroniclers (click here for my earlier-mentioned ShukerNature coverage of these latter cryptids).

GIANT EELS IN OHIO?

Although giant eels are a popular identity for water monsters, of both the marine and freshwater variety, because the size of eels is notoriously difficult to gauge accurately in the wild due to their sinuous movements and usual lack of background scale for precise length estimation this means that eyewitness reports of giant specimens are normally difficult to take seriously – which is why the following account is so significant. On 3 February 2015, Facebook friend Chris R. Richards from Covington, Washington State, USA, posted on the page of the Facebook group Cryptozoology the following hitherto-unpublished report of a huge freshwater eel that he and his father had personally witnessed during the 1990s:

I believe whole heartily in giant eels. I saw one as long as my canoe back in the later nineties. They could result in sea monster claims. Hocking River Ohio. Directly off the side of the canoe in clear water near upper part of river. At first thought it was a tree with algae in water, then saw the head and realized the "algae" was actually a frill. The animal was thicker than my arm. The head was at the front of the 15ft Coleman canoe and the tail end trailed behind my back seat. At the time this was amazing to both my father and I. Only later did I come to fully appreciate how amazing this sighting was. I got to see it the longest as we slowly passed it and I was in the back of the boat. [The eel was] 12 to 15 ft.

The frill was presumably the eel's long, low dorsal fin, which runs along almost the entire length of the body in freshwater anguillid (true) eels. What makes this report so exciting is that there is an unambiguous scale present in it – the known length of the canoe, alongside which the eel was aligned, thereby making its total length very easy to ascertain.

American eel (public domain)

American eel (public domain)The only such species recorded from Ohio is the common American eel Anguilla rostrata, which officially grows up to 4 ft long. Consequently, judging from the scale provided by the canoe, the eel seen by Chris and his father was 3-4 times longer than this species' official maximum size.

Assuming their report to be genuine (and I'm not aware of any reason to doubt it), there seems little option but to assume, therefore, that bona fide giant freshwater eels do indeed exist, at least in the Ohio waterways, which is a remarkable situation and clearly of notable cryptozoological interest.

Reconstruction of the possible appearance of the Ganges giant blue mystery eel (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Reconstruction of the possible appearance of the Ganges giant blue mystery eel (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Published on March 18, 2015 20:15

March 8, 2015

THE CAMP FIRCOM CADDY CARCASE - MONSTER OR MONTAGE? - REVIEWING A LITTLE-KNOWN SEA SERPENT CONTROVERSY

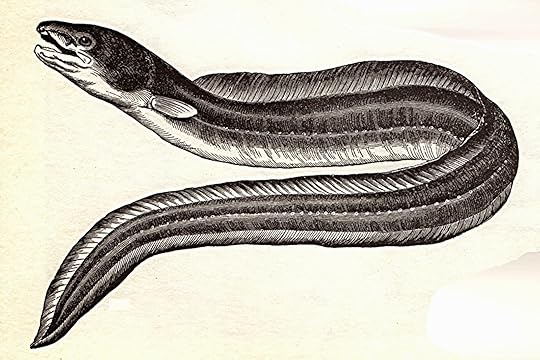

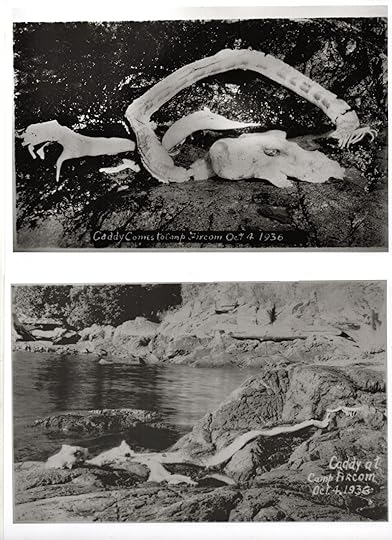

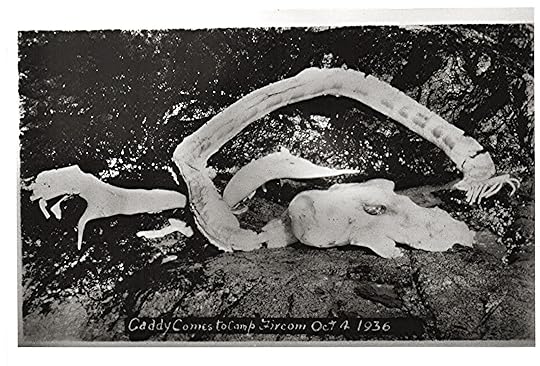

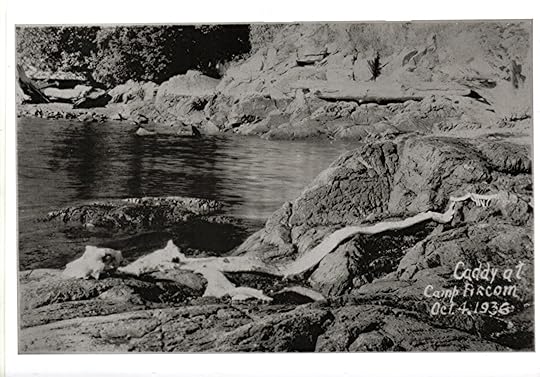

The two picture postcards (#1 top, #2 bottom) depicting the Camp Fircom Caddy carcase (public domain/FPL)

The two picture postcards (#1 top, #2 bottom) depicting the Camp Fircom Caddy carcase (public domain/FPL)Few cryptozoologists will be unaware of the Naden Harbour carcase – an enigmatic serpentine animal carcase measuring 10-12 ft long, sporting what looked like a camel-like head, long neck, pectoral flippers or fins, a very elongate body, and a fringed tail-like section that may have been a pair of hind limbs and/or a bona fide tail. It had been removed from the stomach of a sperm whale by flensing (blubber-removing) workers in a whaling station at Naden Harbour in Canada's Queen Charlotte Islands one day in early July 1937, and had then been placed by them on a long table draped with a white cloth and photographed.

Tragically, the carcase is apparently long-vanished, presumably discarded, but three photographs of it remain, and portray a creature that is sufficiently strange in appearance to have incited considerable controversy ever since as to its possible identity. Almost exactly 20 years ago and based upon the surviving photographic evidence, Dr Ed L. Bousfield, currently a Research Associate at Toronto's Royal Ontario Museum, and Prof. Paul H. LeBlond, now retired from the Department of Oceanography at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, designated the Naden Harbour carcase (believed to be of a juvenile individual) as the type specimen of the longstanding serpentiform mystery beast informally known as Caddy or Cadborosaurus, the Cadboro Bay sea serpent, frequently reported off the northern Pacific coast of Canada and the U.S.A. In a paper constituting a supplement to the inaugural volume of the scientific journal Amphipacifica, published on 20 April 1995, based upon this specimen's morphology as seen in the photos they proposed that Caddy was a living, modern-day species of plesiosaur and they formally named its species Cadborosaurus willsi.

The Naden Harbour carcase - a juvenile Caddy specimen? (G.V. Boorman/public domain)

The Naden Harbour carcase - a juvenile Caddy specimen? (G.V. Boorman/public domain)Far less familiar than the Naden Harbour carcase photographs, conversely, are two Caddy-linked pictures that were first brought to my notice 20 years ago. To my knowledge, they had never previously received any cryptozoological attention, and even today they remain little-publicised. Consequently, this present ShukerNature article reviews for the very first time the history and most notable opinions that have been offered to date in relation to the tantalising object(s) that these pictures depict.

Back in the mid-1990s, I was writing the text to my forthcoming book, The Unexplained: An Illustrated Guide to the World's Natural and Paranormal Mysteries , and Janet Bord of the Fortean Picture Library was supplying me with a number of illustrations for possible inclusion within it.

My book

The Unexplained

(1996) © Dr Karl Shuker)

My book

The Unexplained

(1996) © Dr Karl Shuker)Unfortunately, she was not able to supply me with any of the Naden Harbour images as these had not been placed with the FPL and there was some degree of uncertainty concerning who owned their copyright at that time (they are now in the public domain). So although I did document it in my book, I couldn't illustrate my coverage with one of the pictures of it. Nevertheless, Janet was able to find a couple of old picture postcards depicting an alleged Caddy carcase washed up at Camp Fircom in British Columbia, Canada, on 4 October 1936 (less than a year before the Naden Harbour carcase was retrieved), and which I had never seen before. Janet did not have any details concerning these pictures on file other than the handwritten captions that were already printed upon them, and I was unable to uncover any mention of them in any of the sources of Caddy information available to me. (As for the actual postcards themselves, I assume from their style and the rather primitive quality of their photographs that they were originally on sale in the Camp Fircom area not long after the carcase had originally been discovered there.)

Frustratingly, moreover, the deadlines for writing and submitting to the publishers each section of the book's text meant that by the time that I'd received these interesting images, I'd already written and submitted my full quota of allotted text for my book's Caddy entry, so I couldn't have documented them there anyway. All that I could do, and which is precisely what I did do, was include the more detailed of the two images (Picture Postcard #1), tagged with the following informative caption: "Postcard depicting an unusual marine carcase, possibly a Caddy, that was found on the beach at Camp Fircom, British Columbia, on 4 October 1936".

The Camp Fircom Caddy carcase, Picture Postcard #1 (public domain/FPL)

The Camp Fircom Caddy carcase, Picture Postcard #1 (public domain/FPL)In truth, however, the more that I looked at these pictures, especially the close-up view afforded by Picture #1, the more confused I became about what precisely I was looking at, because they certainly didn't resemble the more traditional supposed sea serpent carcases that wash up from time to time and invariably prove to be the highly decomposed, distorted remains of sharks, whales, or oarfishes. Indeed, by the time that my book was published in 1996, I considered it likely that they showed nothing more than a collection of sea-divulged debris, which may or may not have been artfully arranged by person(s) unknown to look monstrous in every sense, and thence cash in (possibly literally, via the sale of the picture postcards depicting this deceiving creation?) on the tradition of sea monster sightings in this part of the world. Nevertheless, I was pleased to have been able to include at least one of these puzzling pictures in my book, just in case it elicited any responses from readers supplying additional information or opinions relating to it. And sure enough, this is precisely what happened.

During the second week of February 1997, I received a detailed report from a then-university zoology student of Southampton, England, documenting his opinion as to what Picture #1 actually showed. That student is now palaeontologist Dr Darren Naish, who, like me, has long been interested in cryptozoological subjects in addition to mainstream zoology. Having viewed the photo at length in my book, Darren reported that although there were certain superficial similarities to the Naden Harbour carcase (large skull-like object with an apparent eye socket, long thin elongate body with a pair of anterior lateral projections sited where pectoral fins might be expected to be), he considered it to be a hoax – consisting of a montage of objects that he suspected had been deliberately chosen and arranged to give the impression of a carcase. The supposed skull, he felt, did not actually possess any definite skull characters, and, tellingly, its eye socket, placed in just the right location to resemble a true eye socket was, in Darren's view, the shell of a mussel. As for the long elongate body, he considered this to be the stem of a large plant, probably kelp, with finger-like projections at its distal or 'tail' end resembling the root-like holdfasts that anchor kelp to rocks. In short, a collection of marine/beach detritus deliberately positioned to look like a serpentiform monster carcase, thus echoing my own view regarding this.

Mindful that he hadn't seen Picture #2, I sent Darren a photocopy of it, which he briefly referred to (and he also included sketches of both pictures) within an expanded, illustrated version of the original report that he had previously sent to me, which was published in the summer 1997 issue of The Cryptozoology Review, now defunct. In it, he reaffirmed his opinion that the carcase was a composite of kelp, mussel shell, and beach rocks. Interestingly, although I could see why he thought that the eye socket in Picture #1's depiction of the skull-like object was a mussel shell, in Picture #2 it seems to me to be a genuine socket, i.e. a hole, because when this picture is enlarged I am sure that the seawater behind the skull-like object can actually be seen through the socket. That aside, however, I definitely concur and reaffirm that the Camp Fircom Caddy may be monstrous in form but is merely a montage in nature.

The Camp Fircom Caddy carcase, Picture Postcard #2 (public domain/FPL)

The Camp Fircom Caddy carcase, Picture Postcard #2 (public domain/FPL)Even so, are the main components of it truly botanical rather than zoological in identity?

At much the same time that I was corresponding with Darren regarding these two pictures, I was also awaiting a response from Prof. LeBlond, to whom I had sent photocopies of the pictures, enquiring his opinion as to what they may portray.

In his letter of reply, dated 3 March 1997, Prof. LeBlond noted that he had seen: "…pictures of a lot of Caddy-like carcasses which have usually turned out to be sharks. Most of them look a lot like the Camp Fircom picture". Of particular interest was his comment:

What makes me think that the Camp Fircom carcass is yet another shark is the uniform roundness of the vertebrae, especially as seen in the upper picture [Picture #1]. The Neah Bay shark bones looked a lot like that: a "log" made of a series of cylindrical vertebrae, without extensions or projections.

Shark remains are sometimes found washed ashore at Neah Bayand elsewhere along the Pacific U.S. state of Washington's coast, and needless to say there are many cases on file (from North America and elsewhere around the world) of such remains being mistaken by eyewitnesses for sea serpent carcases.

Basking shark vertebrae (© www.mylargs.comnaturemonstermonster2.shtml)

Basking shark vertebrae (© www.mylargs.comnaturemonstermonster2.shtml)Paul also stated that he had forwarded the photocopied pictures to Dr Bousfield, who very kindly wrote to me on 27 August 1997 with his own comments regarding them:

I tend to agree with Paul that the Camp Fircom carcase is very probably that of a basking shark. Local beach carcasses that have been attributed to "Caddy"-like animals appear similar to the remains of your photograph. Virtually all such remains, reported (with photographs) during the past 70+ years, have proven to be those of the large pelagic shark species common in surface waters of the North American Pacific coastal marine region.

The only photographs considered by us as reliably that of a "Caddy" carcass, are three fairly good images, taken from three different camera angles by two different photographers, at the Naden Harbour whaling station in 1937, and now deposited in the B.C. Provincial Archives here in Victoria.

Two of the three Naden Harbour carcase photographs are included in their book Cadborosaurus: Survivor From the Deep, published during the same year, 1995, as their more formal Amphipacifica paper.

Cadborosaurus: Survivor From the Deep

(1995)(© LeBlond & Bousfield/Horsdal & Schubart)

Cadborosaurus: Survivor From the Deep

(1995)(© LeBlond & Bousfield/Horsdal & Schubart)So might the Camp Fircom Caddy carcase be a highly-decomposed shark, or at least include some shark-derived components within a heterogeneous array of objects?

For a long time, this enigmatic entity attracted little if any additional attention other than its two pictures featuring in a handful of East European cryptozoological websites but with no attendant comments concerning them. In a guest article regarding the Naden Harbour carcase that appeared in Jay Cooney's Bizarre Zoology blog on 17 June 2013, however, Florida-based cryptozoologist Scott Mardis did briefly refer to the Camp Fircom carcase and included Picture #1. After noting Darren's opinion regarding its composition and then comparing it to some illustrations of basking shark vertebrae, Scott commented: "I'm not so sure, because it looks very basking sharky to me", and I agree that there is indeed a notable degree of similarity between the supposed carcase's elongate body and the vertebral column of a shark.

On 17 February of this present year, Darren posted his detailed sketch of Picture #1 on his Facebook page's timeline and tagged me in his post. He also now opined that the carcase's body certainly resembled a shark's vertebral column (thus updating his original identification of it as a possible plant stem back in his article from 1997), but remained unsure as to the nature of the carcase's other components. This elicited on my own Facebook page's timeline a number of detailed responses from German cryptozoological researcher Markus Bühler, who illustrated them with relevant images obtained online. Like Paul, Ed, Scott, myself, and now Darren too, Markus favoured a shark identity for at least some of the objects constituting the Camp Fircom Caddy carcase, and I am summarising as follows the various points that he raised in relation to this.

Screenshot of the opening posts in the Camp Fircom Caddy carcase discussion thread on my Facebook page's timeline – there were far too many posts to include screenshots of the entire thread, but it yielded an extremely interesting exchange of views

Screenshot of the opening posts in the Camp Fircom Caddy carcase discussion thread on my Facebook page's timeline – there were far too many posts to include screenshots of the entire thread, but it yielded an extremely interesting exchange of viewsWith respect to the carcase's supposed skull, Markus considered that Picture #1 possibly does show a cranium with a hole, but in a predominantly dorsal view, so that the hole is not an eye socket but is instead the epiphyseal foramen (a large dorsally-sited cranial opening that houses the pineal body in living sharks). If so, then the projections above and below it could be the upper parts of the laterally-sited eye orbits. He also noted that the skull may be from a shark but not a basking shark, perhaps instead from a species with very different cranial proportions from those of a basking shark, which could explain why it does not provide an exact match with a basking shark cranium.

Markus considered that shark-derived contributions to the carcase might principally consist of its cranium and vertebral column, but he did also wonder whether, if so, the finger-like projections at the right-hand side of the carcase's body, originally labelled as kelp holdfasts by Darren, may be parts of the shark's fin rays and he posted some online photos of a fully defleshed shark carcase found underwater that bore exposed fin rays resembling the 'fingers' of the Camp Fircom conglomerate. In addition, as he correctly pointed out, in some species of shark the spinal column between cranium and caudal fin is surprisingly short, so these 'fingers' may specifically be exposed rays from the lower lobe of the shark's caudal fin.

Concluding the Camp Fircom carcase discussion thread on my FB timeline, Darren reflected that he'd never considered that a shark may have contributed to this creation when preparing his original article, but still felt that its overall appearance was the result of an assortment of debris and that this was the key point. That is, the alleged Camp Fircom Caddy carcase was merely a conglomeration of objects from different sources, not a single entity – and I agree entirely with this assessment.

Reconstruction of the possible appearance in life of an adult female Caddy (© Tim Morris)

Reconstruction of the possible appearance in life of an adult female Caddy (© Tim Morris)Regardless of whether its body derives from kelp or a shark, or whether its 'fingers' are holdfasts or fin rays, or whether its skull is a rock or a shark cranium, or whether the latter object's hole is an eye socket or an epiphyseal foramen or even just a deceptive mussel shell, there can be no doubt that what the Camp Fircom composite is not, and never could be, is a deceased Caddy. In short, this is one cryptozoological carcase (and mystery) that, finally, not so much rests in peace as in pieces – very different pieces from a range of very different origins.

I wish to offer my sincere thanks to Dr Ed Bousfield, Markus Bühler, Prof. Paul LeBlond, Scott Mardis, and especially Dr Darren Naish for sharing their views with me concerning the Camp Fircom Caddy carcase, and to Janet Bord of the Fortean Picture Library for so kindly bringing its two picture postcard images to my attention all those years ago.

Artistic representation of Cadborosaurus willsi (© Thomas Finley)

Artistic representation of Cadborosaurus willsi (© Thomas Finley)

Published on March 08, 2015 17:19

March 2, 2015

SPIDERS WITH WINGS? IMPLAUSIBLE THINGS!

Never in the long and very diverse history of spiders – a very significant arachnid order (Araneae) whose lineage dates back more than 300 million years according to the known fossil record – has there ever been a spider with wings. And why should there be? Virtually all spiders display a lifestyle that has no place or need in it for wings, relying upon stealth and ambush to survive and to capture their prey, not flamboyant aerial activity like some bizarre eight-legged dragonfly. Nevertheless, this has not prevented flying spiders from winging their way every so often through both hard-copy and online media reports – to the delight of connoisseurs of the strange and uncanny, and to the despair of hardcore arachnophobes! So here are three of the most entertaining and engrossing accounts that I have seen which showcase these faux yet fabulous fliers of the spider kind.

A WINGED TERROR ON TUMBLR

During 2012, several users of the website Tumblr posted online what initially looked like a bona fide but unidentified newspaper clipping of a supposedly newly-discovered species of winged spider. The clipping consisted of a b/w photograph of the spider in question, entitled 'Scientist discovers winged spider', but with no accompanying details concerning it or its discovery. A close look at the photo, however, soon revealed that it was a not-especially efficient exercise in image manipulation of the photoshopped variety. The spider depicted was in fact a common (and wingless!) species of fishing (aka raft) spider belonging to the genus Dolomedes.

The fake report of a winged spider featuring a photoshopped image of an ordinary wolf spider (creator/s unknown)

The fake report of a winged spider featuring a photoshopped image of an ordinary wolf spider (creator/s unknown)In addition, as later revealed on the famous hoax-busting Snopes website as well as on several others too, the original photograph of it that had subsequently been manipulated by person(s) unknown to yield the winged spider is one that had been snapped on 23 September 2007 at Durham in North Carolina by Will Cook from Duke University in Durham, and had appeared (it still does in fact) on the website North Carolina Spider Photos ( here is a direct link to this photo on the latter website).

Will Cook's original, undoctored photograph of a Dolomedes wolf spider (© Will Cook)

Will Cook's original, undoctored photograph of a Dolomedes wolf spider (© Will Cook)On 10 March 2014, the fake clipping and photo were revisited by the website of a UK computer services company, Digital Plumbing, which provided an extensive report about them, including details of how the winged spider, which in this report was unscientifically named Volat-Araneus (it should have been the other way around and italicised, of course, i.e. Araneus volat, if the aim was for it to resemble a genuine taxonomic binomial), preyed upon the poisonous (and real) false widow spider Steatoda nobilis.

A false widow spider Steatoda nobilis (public domain)

A false widow spider Steatoda nobilis (public domain)However, the report was peppered with clues that it was a hoax, and indeed, halfway through it its (unnamed) writer confessed this openly, explaining that the report's sole purpose had been to attract the attention of readers, who would now, the writer hoped, take note that this website was that of a company offering technology repairs and other services, as detailed in the remainder of the report. In short, Digital Plumbing's report was a very novel marketing ploy, quite possibly the first one ever to utilise a non-existent winged spider to attract potential customers.

A WINGED SPIDER VIDEO AND A WINGLESS MISNOMER

Flying spider #2 has only appeared once (to my knowledge) – as an even less convincing photoshopped image presented in an extremely brief YouTube video uploaded on 15 October 2013 by Brian Griffin under the title 'Have Scientists Discovered a Winged Spider?' (click here to watch it).

In it, mention is made of the fact that a species called the long-winged kite spider is already known to science. This is perfectly true, the species in question being a forest-dweller known formally as Gasteracantha versicolor, which is native to the subtropics and tropics of eastern, central, and southern Africa, as well as Madagascar. However, 'long-winged' is something of a misnomer, because its 'wings' are not of the membranous, flight-producing variety. Instead, they are a pair of immobile sclerotised spines, borne laterally upon the opisthosoma or abdominal section of this spider's body in the adult female.

Gasteracantha versicolor

, female, in South Africa's Krantzkloof Natuurreservaat (© JMK/Wikipedia)

Gasteracantha versicolor

, female, in South Africa's Krantzkloof Natuurreservaat (© JMK/Wikipedia)THE ITALIAN TOMB SPIDER – ENCOUNTERED IN THE CATACOMBS

Far older and also far more intriguing than the previous two examples is the third member of this trio of winged wonders – albeit this time a truly grotesque Lovecraftian horror, a cryptic cryptid from the crypts in fact, known as the Italian tomb spider.

I first learnt of this macabre entity courtesy of British cryptozoological archive peruser Richard Muirhead, who sent me an unlabelled review report of an article that had originally appeared in the Pall Mall Gazette. Happily, I was soon able to trace the original source of this review report – namely, the San Francisco Call, which had published it on 29 November 1896. The report makes such compelling if unnerving reading that I am reproducing it in its entirety below – the first time, as far as I am aware, that it has ever appeared in an online cryptozoological article:

San Francisco Call , Volume 80, Number 182, 29 November 1896

ITALY'S TOMB SPIDER

A Thing So Odd That It is Believed to Exist Only in Imagination.

The people of Italy believe in the existence of a wonderful creature which, for the want of a better name, is called the tomb spider. The entomologists know nothing of this queer beast, and declare that it only exists in the fancy of the superstitious persons and those whose curiosity or business makes it necessary for them to explore old ruins, tombs, catacombs, etc. According to the popular account the tomb spider is of a pure white color, has wings like those of a bat, a dozen horrid crooked legs and a body three or four times the size of the largest tropical American tarantula.

The accounts of this queer insect and his out-of-the-way places of abode are by no means common, and on that account the information concerning him which we will be able to give the "curious" is very meager. Any Italian will tell you that such a creature exists, however, and that he is occasionally met with in old mines and caverns, as well as in tombs and subterranean ruins. The London Saturday Review has an article from a correspondent who was present when some Roman workmen unearthed a church of the fifth century. He says: "We were standing by one of the heavy pillars that had originally supported the roof, when something flashed down from the pitchy darkness overhead and paused full in the candle-light beside us, at about a level with our eyes. It was distinctly as visible as a thing could be at a distance of three feet, and appeared to be an insect about half the size of a man's fist, white as wax and with its many long legs gathered in a bunch as it crouched on the stone.

"Our guide had seen, or at least heard of this uncanny insect of ill omen before, but was by no means reconciled to its presence, as his notions proved. He glanced around uncomfortably for a moment and then moved away, we following. It seems really a bit queer, but it is said that the strongest nerves give way in the presence of this insect of such ghostly mien. Even today this uncanny apparition is said to be an unclassified monster — an eternal mystery. When the grave spider is encountered by those opening tombs and vaults it is thought to be a 'sign' of death to one of the workmen or some member of his family." - Pall Mall Gazette.

An almost identical account also appeared in another American newspaper, the Sausalito News, on 23 January 1897.

Vintage engraving of catacombs

Vintage engraving of catacombsWhat can we say about such a bizarre report? The spider, if indeed we can apply such a name to a creature sporting wings and a dozen legs, is unlike any life form known either upon or beneath the surface of Planet Earth, even if we generously assume that it may be a grossly exaggerated or embroidered description of a pallid form of bat or an exceptionally large moth.