Karl Shuker's Blog, page 38

May 20, 2015

A GIANT MYSTERY SALAMANDER FROM CALIFORNIA, AND A GIANT VERY SILLYMANDER FROM VIETNAM

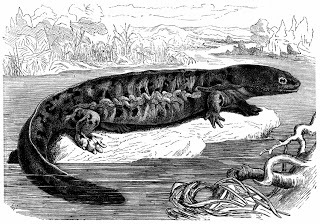

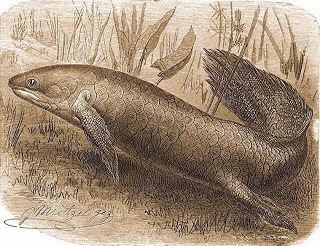

The hellbender, indigenous to the eastern USA, 19th-Century engraving (public domain)

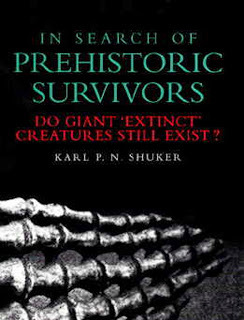

The hellbender, indigenous to the eastern USA, 19th-Century engraving (public domain)Only the Chinese giant salamander Andrias davidianus and its Japanese relative A. japonicus are bigger than North America's largest known salamander species - the hellbender Cryptobranchus alleganiensis. Officially confined to the eastern United States, the hellbender can attain an impressive total length of up to 2.5 ft. However, as I have previously documented on ShukerNature (click here ), and in my book In Search of Prehistoric Survivors (1995) too, there are also some very intriguing unconfirmed reports on file attesting to the supposed existence in the western United States (in particular California) of mysterious salamander-like creatures that are allegedly even bigger than the hellbender.

Unfortunately, these reports generally date back many years, suggesting that even if such animals did once exist there, they no longer do so – which is why I was very happy to receive recently the following first-hand details concerning a most interesting 21st-Century sighting of an apparent giant salamander in California, but which have never been made public…until now.

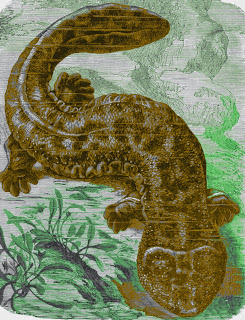

19th-Century colour-tinted engraving of a Japanese giant salamander viewed underwater (public domain)

19th-Century colour-tinted engraving of a Japanese giant salamander viewed underwater (public domain)The details were sent to me by the eyewitness in question via a series of emails, which she has kindly given me permission to document publicly as long as I do not release her name (which I have on file). So I shall simply refer to her here as Prunella (not her real name).

I received Prunella's first email on 1 March 0f this year, which read as follows:

"In 2005 I saw a giant salamander or newt walking along a path in Redwood Park in Arcata, California. It was reddish brown mottled and was 4-5 feet long, it was huge. I had a 10 year old boy with autism that is nonverbal and my cell phone didn't have a camera. It had just rained and was early in the morning. The creature was walking slowly and was all the way off the ground it didn't have a flat head like those other giant salamanders. It really looked more like a newt but all the newts I saw when I googled were so small. I just have no clue what this was and I have always wondered about it. I was so close to it I could have touched it so there is no mistaking what I saw. I just wish I had my iPhone then. There must be more people that have seen it but have no way of reporting things like this. I just hope they are really discovered and then protected."

I swiftly emailed Prunella back, requesting more details concerning this remarkable creature's morphology. I also included two links to videos currently accessible on YouTube – one showing some hellbenders (click here ), the other showing a Japanese salamander on land (click here ), and I asked her if her mystery beast resembled either of these known species. On 6 March, I received her second email:

"Thank you for replying back! I watched the videos that you sent and the salamander I saw was so much bigger than the hellbenders and it looked different. It didn't have that weird ruffled skin and it walked off the ground. The colors that it had looked similar to this [she enclosed a photograph of a Californian coastal giant salamander Dicamptodon tenebrosus, see below] but not exactly the same."

The photograph that Prunella enclosed with her first of two emails sent to me on 6 March 2015, and which she'd accessed

here

on the Fieldherpforum website (© Mike Rochford/Fieldherpforum.com)

The photograph that Prunella enclosed with her first of two emails sent to me on 6 March 2015, and which she'd accessed

here

on the Fieldherpforum website (© Mike Rochford/Fieldherpforum.com)Prunella's email continued…

"The shape of it was like this one too with how the head and tail looks except that the legs were a lot bigger to carry the weight of the creature. I really want someone to find one of these again. I told one of the girls at work about it and she told me her boyfriend saw one in brush that he was clearing that was about a foot shorter than the one I saw. I'm not sure where he saw it though. I have taken many walks in the forest hoping to see it again but no luck. How long do salamanders live? Are they like tortoises where they keep growing and growing? Redwood Park is part of the community forest and goes for acres and acres so I think it's possible that there are animals in there that people just don't know about.

"Please tell my story. I hope that more people have information about this and I would love to be kept in the loop. Can you please leave my name out of it though?

"Thanks."

After receiving from me some emailed answers to her questions plus various additional queries of my own, Prunella sent me a further email later that same day:

"The day that I saw this creature was a very wet day. It had just rained so everything was wet. Also, the redwood forest is usually very damp and there are streams everywhere. The brush would also be very damp in a forest like this so I can see why a salamander would be living in brush in a redwood forest. The skin of this thing was smooth and looked wet and slimy, it didn't have any scales at all. I really don't think it was a lizard.

"Maybe its legs were just more sturdy because it needed to walk around a bit and had to develop them to hold its huge body. Maybe it was an adaptation so it could walk around and look for slugs to eat or something. I hope more people have seen it and reply to your letter. I really want to get to the bottom of this."

Judging from her detailed, three-email report of what she had seen, there seems little doubt that if her testimony is true (and I see no reason to doubt it), Prunella did indeed encounter some unexpectedly large form of salamander (as opposed to a lizard) in Arcata, California's Redwood Park, but what could it have been?

Preserved giant salamander at Museum Schloss Rosenstein in Stuttgart, Germany (© Markus Buhler)

Preserved giant salamander at Museum Schloss Rosenstein in Stuttgart, Germany (© Markus Buhler)Seemingly not an out-of-place hellbender, judging from the clear differences from this latter species as outlined by her; and the chances of it being either a Japanese or a Chinese giant salamander that had somehow absconded from captivity seem highly remote – if only because these species are so rare and hence so seldom maintained in captivity that if there was such a creature in this area that had indeed escaped, its owner would surely have quickly alerted the authorities in a bid to locate and recapture this highly valuable animal with all speed. As for the species whose photo she'd enclosed with her second email, namely California's coastal giant salamander Dicamptodon tenebrosus: notwithstanding its 'giant' appellation, this species barely exceeds 1 ft in confirmed total length – unless, perhaps, a few freakishly out-sized specimens also exist, currently unconfirmed by science?

Both Prunella and I would very much like to know if other people have seen a similar animal in this same locality or elsewhere in California (she did mention that the boyfriend of one of her work colleagues had allegedly seen a smaller specimen, though she didn't know where), so if you have done, I'd greatly welcome any details that you can post here or email to me privately – thanks very much.

The human-sized Chinese giant salamander…with a human (© NGT/National Geographic Creative )

The human-sized Chinese giant salamander…with a human (© NGT/National Geographic Creative )By sheer coincidence, only a week after I had received Prunella's initial email regarding her giant mystery salamander in California, an extraordinary story hit the headlines concerning the apparent capture of a giant mystery salamander in Vietnam – a country not known to harbour any such species. Not surprisingly, therefore, it attracted considerable interest online, but most especially on Facebook. For this where the story had begun, when in early March 2015 a 25-year-old Vietnamese man named Phan Thanh Tung had claimed on his Facebook page that he had pulled the mysterious 3-ft-long creature out of a pond near his home in northern Vietnam's Vinh Phuc region. He had also posted some top-quality colour photographs of it on his page.

These revealed that although the creature superficially resembled the larger giant salamander of neighbouring China, it exhibited various differences too, thereby perplexing local environment officials who had examined the photos, and spurring various other viewers into suggesting that it may represent an entirely new, hitherto-undescribed species.

The mysterious Vietnamese giant salamander (original copyright owner unknown to me/photo-manipulated by Tung Nguyen)

The officials, however, were not merely perplexed but also very alarmed, because Phan Thanh Tung announced that he had sold the animal (but would not reveal its new owner's identity or whereabouts) and at least one of his photos showed it alive but placed upon a large dining tray with a chopping board in disturbingly close proximity! As a result, the officials were so determined to track the animal down and save it that they called in the police to assist them in searching for it – always provided, of course, that the poor creature had not already been killed and eaten, as a number of social website commentators feared. (Tragically, Chinese giant salamanders remain a much sought-after culinary delicacy in their native homeland notwithstanding their IUCN status as a critically endangered species.)

Happily, however, this proved not to be the case – for the simple reason that the whole episode was soon exposed as a hoax. When summoned by police to an interview shortly after his story had made headlines worldwide, Phan Thanh Tung shamefacedly confessed that he'd made the whole thing up. As for the photos, he'd found them online and they had originally depicted a normal Chinese giant salamander, but after downloading them he'd edited them via photo-manipulation in order to create a creature that looked different from all known species, and had then uploaded them together with his fake story onto his FB page in order to attract some attention to himself – too much, as it turned out.

Not so much a salamander, then, as a sillymander, and a very silly one at that.

A second photograph of the mysterious Vietnamese giant salamander (original copyright owner unknown to me/photo-manipulated by Tung Nguyen)

Published on May 20, 2015 14:57

May 16, 2015

DROP BEARS, FEATHERED KANGAROOS, AND OTHER FRAUDULENT FAUNA DOWN UNDER

Beware of the drop bear?!! (Photo-manipulator unknown/original photograph © Oz_drdolittle/Flickr)

Beware of the drop bear?!! (Photo-manipulator unknown/original photograph © Oz_drdolittle/Flickr)No country's corpus of traditional myths and folklore would be complete without also containing various tongue-in-cheek yarns concerning all manner of bizarre and sometimes deliciously deadly beasts that exist only in the twinkle of the storyteller's eye. And if those listening to these tall tales actually believe them, the twinkle becomes a veritable supernova!

Bearing in mind that even its authentic wildlife is truly extraordinary, it should come as no surprise to learn, therefore, that Australia's fauna of the fraudulent kind is particularly memorable, as demonstrated by the following selection of examples.

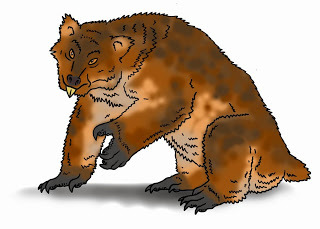

Artistic representation of the drop bear in life (© Tim Morris)

Artistic representation of the drop bear in life (© Tim Morris)The most famous of these Antipodean ambiguities is the drop bear. Closely related to the koala but larger and darker in fur colour, the drop bear shares its cuddly appearance, but not its inoffensive nature. On the contrary, the drop bear is greatly feared by anyone journeying through heavily-wooded outback territory, because it is known to lie in wait on overhead branches, and should anyone walk unsuspectingly beneath, this monstrous marsupial will drop unerringly down upon and dispatch its hapless victim with its lacerating claws and savage teeth. The only way to ensure safe passage through drop bear-inhabited terrain is to smear Vegemite behind your ears, which should be more than sufficient to deter even the most voracious drop bear.

Do these kangaroo feathers look like emu plumes to you? :-) (public domain)

Do these kangaroo feathers look like emu plumes to you? :-) (public domain)Less daunting and much more exotic is the feathered kangaroo. The main claim to fame of this elusive creature is that its long white plumes are used to decorate the head-dress of certain Australian soldiers, namely the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) light horsemen.

To the uneducated eye, these look remarkably like emu plumes, but when asked, the AIF themselves are happy to confirm, with straight faces manfully employed, that they are indeed kangaroo feathers.

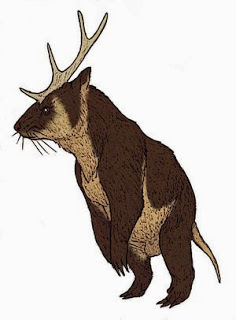

Artistic representation of the gunni in life (© Connor Lachmanec)

Artistic representation of the gunni in life (© Connor Lachmanec)Whereas North America has the jackalope, Australia boasts the gunni – an eyecatching marsupial equivalent, consisting of a wombat sporting a showy pair of antlers. To date, however, only one example has been procured – the handsome taxiderm specimen, complete with striped back and hindquarters, plus a distinct tail, formerly on display in the visitors’ information centre at the tourist town of Marysville in Victoria. It was presented to the centre by local ranger Miles Stewart-Howie, together with a detailed account of this pseudo-species’ equally fictitious history, which was duly displayed alongside it.

Tragically, however, this unique specimen was destroyed when the centre burnt down during the major onslaught of bushfires that raged through Victoria during February 2009.

The only known preserved specimen of the gunni, now destroyed (© Ken Irwin)

The only known preserved specimen of the gunni, now destroyed (© Ken Irwin)Staying with the subject of fabricated fauna Down Under: According to local tradition, a peculiar fish inhabited a single water-hole in Queensland’s Burnett River. Superficially, it resembled the Australian lungfish Neoceratodus forsteri that also lived in this river, but was instantly distinguished from that latter species and indeed from all known fishes by virtue of its long flat spatula-shaped beak.

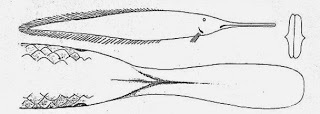

19th-Century engraving of the Australian lungfish (public domain)

19th-Century engraving of the Australian lungfish (public domain)Dubbed the ompax by Australian ichthyologist Count Castelnau during the 1870s, a single specimen of it was eventually obtained, and its species was formally christened Ompax spatuloides. During the 1920s, however, the true nature of this specimen, and the ompax as a whole, was exposed, when a writer discovered that the specimen had been cleverly constructed from the body of a mullet, the tail of an eel, and the beak of a platypus! Exit the ompax from the ichthyological catalogue!

Sketches of the ompax from 1930 (public domain)

Sketches of the ompax from 1930 (public domain)Incidentally: despite the fact that the drop bear is no more likely to be discovered than are any of the so-called 'fearsome critters' from North American lumberjack/frontier folklore (click here for three feline examples), this has not prevented it from being 'identified' by some as a possible surviving thylacoleonid or marsupial lion (which was distantly related to the koala). Nor has it prevented a number of websites labelling the photograph opening this present ShukerNature blog post as depicting a bona fide drop bear, though I strongly suspect (or at least hope!) that they did so merely in jest, not as a serious statement of assumed fact.

What this startling photograph (popularly dubbed the 'Angry Koala') does portray is a very wet koala, but no genuine koala has jaws like those snarling in savage fury at the camera. In reality, they are the jaws of some carnivorous creature that have been deftly added by person(s) unknown via photo-manipulation techniques to a photograph of a normal koala that was snapped on 30 January 2009 by an Australian photographer with the Flickr username Oz_drdolittle. It was one of three koalas sitting in a tree near his home in Adelaide, South Australia, during a 12-day heatwave, and which his garden's water sprinklers sprayed with water, thereby enabling them to cool them off. Below is his original, non-manipulated photograph, sans snarling jaws, and click here for his Flickr page that contains full details and additional photographs of what is now a world-famous koala, thanks to both its original unmodified picture and its drop bear 'alter ego' version having gone viral online during the past 6 years.

The original, unmodified koala photograph (© Oz_drdolittle/Flickr)

The original, unmodified koala photograph (© Oz_drdolittle/Flickr)

Published on May 16, 2015 21:19

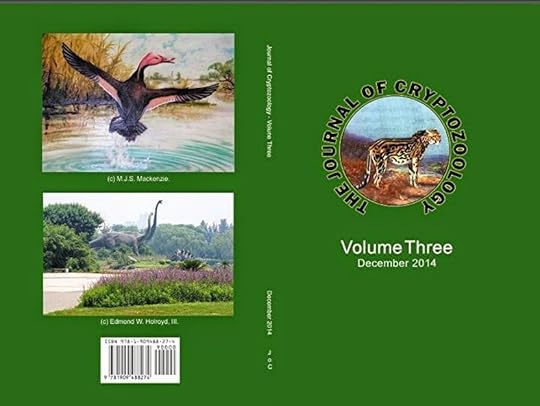

May 13, 2015

MOCKERY BIRDS AND TURQUOISE DRAGONS - A SHUKERNATURE TOP TEN LISTING OF LESSER-KNOWN VINTAGE CRYPTOZOOLOGY-THEMED NOVELS

The Mockery Bird

by Gerald Durrell – Fontana paperback edition, 1990 (© Gerald Durrell/Fontana Books)

The Mockery Bird

by Gerald Durrell – Fontana paperback edition, 1990 (© Gerald Durrell/Fontana Books)Today, there are numerous novels whose themes deal with cryptozoological beasts or scientifically-known but out-of-place animals, and many have become bestsellers, some even giving rise to blockbuster films too – but this has not always been the case. Decades ago, for every unequivocal success story like Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's The Lost World or Edgar Rice Burroughs's The Land That Time Forgot, there were other, less epic but no less interesting and certainly no less readable novels that for whatever reason(s) failed to attract widespread attention, and for the most part have long since faded to varying degrees into the forlorn mists of undeserved but inevitable literary obscurity and out-of-print status.

As a connoisseur of wildlife-related curiosities in whatever form they may take, over the years I've made a point of collecting – and reading, naturally – as many of these unfairly forgotten or tragically neglected works of natural history fiction as I could find. So here – in the hope that perhaps this much-deserved (albeit all-too-brief) return to the spotlight may help to introduce them to a whole new audience and gain for them a sizeable new fan base – is, in no particular order, a ShukerNature Top Ten of personal favourites of mine drawn from the somewhat esoteric literary genre of lesser-known vintage novels that contain a mystery creature or out-of-place (OOP) animal theme.

Or, to put it another, rather more concise way, here imho are ten of the best crypto-novels that got away.

Cat

by Andrew Sinclair – Sphere paperback edition, 1977 (© Andrew Sinclair/Sphere Books)

Cat

by Andrew Sinclair – Sphere paperback edition, 1977 (© Andrew Sinclair/Sphere Books)CAT [vt THE SURREY CAT ] – Andrew Sinclair (Michael Joseph: London, 1976)

Book blurb: The Cat was at large! The people of the quiet Surrey village of Wittlemead called it simply 'The Cat', for they could find no better words to describe the ravening black beast that prowled the nearby woods. The Cat was deadly, inexorable and fearless; no living thing, human or animal, was safe while it lived. Peter Gwynvor, Master of the local hunt, spearheaded the efforts to track down and kill the Cat before it could strike yet again. But as his campaign progressed he realised that the conflict between man and beast was merely a mirror for another, far deeper and more personal conflict within himself — a conflict he hardly dared acknowledge. The Cat had become the symbol of Peter's secret fears — and only when they met face to face, to kill or be killed, would those fears finally be resolved...

ShukerNature comments: Today, mystery cats are the subjects of many novels, for adults and children alike. A fair number of these have been set in Britain, but as far as I am aware this was the very first one. Without giving too much of the plot away, its ferocious feline antagonist is a highly exotic escapee originating in the steamy jungle marshes of Sumatra, the like of which has never before been seen in the West.

Rare Bird

by Kenneth Allsop – Jarrolds hardback 1st edition, 1958 (© Kenneth Allsop/Jarrolds)

Rare Bird

by Kenneth Allsop – Jarrolds hardback 1st edition, 1958 (© Kenneth Allsop/Jarrolds)RARE BIRD – Kenneth Allsop (Jarrolds Publishers: London, 1958)

Book blurb: When Philip Parfitt, secretary of the local Natural History Society, finds black-winged stilts actually nesting near his Wiltshire home – the first time in Britain for 200 years – his village becomes almost a mad-house. Down come the London bird protectionists, TV units, nature broadcasters and publicists, an army of photographers, reporters and feature writers...all the mendicants of sensation.Kenneth Allsop's experience of Fleet Street and his life-long interest in bird-life combine to give an unusually authentic country background to this extravaganza of the ballyhoo age, which might (almost) really have happened.

ShukerNature comments: Although the black-winged stilt Himantopus himantopus is an uncommon visitor to Britain, this very distinctive species of wader has bred here occasionally – namely, in Nottingshamshire during 1945, in Norfolk during 1987, and in both Kent and West Sussex during 2014.

Smith's Gazelle

by Lionel Davidson – Book Club Associates hardback edition, 1972 (© Lionel Davidson/BCA)

Smith's Gazelle

by Lionel Davidson – Book Club Associates hardback edition, 1972 (© Lionel Davidson/BCA)SMITH'S GAZELLE – Lionel Davidson (Jonathan Cape: London, 1971)

Book blurb: Hamud the one-eyed Arab shepherd, righteous murderer of murderers, flees from retribution to the depths of a haunted ravine near the Palestine border. Instead of souls and djinns, he finds there only bones and boulders – and the last pregnant representative of an extinct species of gazelle named Smith. As animal and vegetable life prosper beneath his care, Hamud comes to see himself as the subject of divine grace: his unworthy life's mission, to repopulate with gazelles the Holy Land.Lionel Davidson's new novel is a delightful entertainment – fresh, funny and wholly charming. He has created three of his most unforgettable characters: the wickedly wise small boy, the delicate – but so prolific – gazelle and the indomitable old man, toiling like an Old Testament archetype in his flowering ravine.

ShukerNature comments: Although Smith's gazelle is a fictitious species, there is at least one bona fide mystery gazelle – the red gazelle Eudorcas rufina. This enigmatic species has never been reported in the wild state, and is known to science only from three museum specimens that were purchased in various markets in Algiers and Oran, northern Algeria, during the late 19th century. Following scientific examination, one of these specimens was unmasked in 2008 as being a specimen of the red-fronted gazelle E. rufifrons.

The People of the Chasm

by Christopher Beck – C. Arthur Pearson hardback 1st edition, 1923 (© Christopher Beck/C. Arthur Pearson Ltd)

The People of the Chasm

by Christopher Beck – C. Arthur Pearson hardback 1st edition, 1923 (© Christopher Beck/C. Arthur Pearson Ltd)THE PEOPLE OF THE CHASM – Christopher Beck (C. Arthur Pearson: London, 1923)

Book blurb: Dick and Monty Vince put their plane aboard the missing Anton Javelot's ship 'Penguin' and sail to Antarctica in search of him. They eventually locate Javelot inside a hidden verdant chasm populated by a tribe of friendly pygmies, a band of very unfriendly bipedal apes, and a diverse assortment of lethal monsters including giant arthropods and a terrifying species of rampaging man-eating mole-pig!

ShukerNature comments: The 'Lost World' sub-genre of cryptozoology-themed novel is represented in the present ShukerNature list by this gripping but long-forgotten volume, which contains some decidedly bizarre mystery creatures. 'Christopher Beck' was a pseudonym adopted by Thomas Charles Bridges (1868-1944), a prolific French-born UK writer who wrote many sci-fi novels and magazine articles, and spent several years in Florida.

Tiger in the Bush

by Nan Chauncy – Puffin paperback edition, 1978 (© Nan Chauncy/Puffin Books)

Tiger in the Bush

by Nan Chauncy – Puffin paperback edition, 1978 (© Nan Chauncy/Puffin Books)TIGER IN THE BUSH – Nan Chauncy (Oxford University Press: Melbourne, 1957)

Book blurb: The Lorenny family lived in a secret valley, hidden so deep in the mountains that no map makers had discovered it, where the rarest creatures lived safe from the menace of hunters or the curiosity of scientists. It was, most of the time, a wonderful place, but there were drawbacks, especially for young Badge, the lonely one of the family, who had never met a stranger yet felt the need of companionship without realizing the hazards it could bring in such a very special place.The crisis came when Dad and the others were away on a prospecting trip, and Badge and his mother were left in charge of the farm. Two friendly strangers appeared and asked to set up camp, and, fatally warming to their friendship and interest, Badge confided to them that the rarest animal of all, the nearly extinct Tasmanian tiger, could still be seen in the valley.The moment he had spoken, he sensed the disaster and, desperate to find a way to undo the damage before the wild and splendid creature was outlawed or killed by too much interest, he embarked on the only plan he could think of, one that was to lead him into real danger...

ShukerNature comments: When this novel was written, it was still widely believed that the thylacine or Tasmanian tiger Thylacinus cynocephalus was merely very rare as opposed to extinct (its current official status, numerous unconfirmed sightings notwithstanding) – back then, the last confirmed specimen had only died 21 years earlier, in 1936.

The White Gorilla

by Henri Vernes – Corgi paperback edition, 1967 (© Henry Vernes/Corgi Books)

The White Gorilla

by Henri Vernes – Corgi paperback edition, 1967 (© Henry Vernes/Corgi Books)THE WHITE GORILLA – Henri Vernes (Éditions Garard: Brussels, 1966)

Book blurb: In the heart of the Dark Continent lurked Niabongha, the white gorilla. Though the natives built images to him, there were vicious white hunters who wanted his life…It was up to Bob Morane to capture the fantastic beast – and to capture it alive. And the dangerous quest meant a battle – not only with the jungle and its inhabitants, but also with his fellow man…

ShukerNature comments: Henri Vernes is the nom-de-plume of Charles-Henri-Jean Dewisme (b. 1918), an extremely prolific French author who has written over 200 action and science-fiction/fantasy novels. More than 50 of these star Bob Morane, a bold derring-do Indiana-Jones-type hero. Vernes's novel The White Gorilla was originally published in French as Le Gorille Blanc back in 1957, but by a remarkable coincidence, just a few months after it was first published in English in 1966 a real-life white gorilla, but only a baby one, was captured alive in the forests of Rio Muni, Spanish West Africa, after its normal-coloured mother had been killed. The only white gorilla ever confirmed by science, it was brought back to Barcelona Zoo in Spain where it was dubbed Little Snowflake and became a major international star for almost 40 years (click here for a full ShukerNature biography of this unique animal).

The Mockery Bird

by Gerald Durrell – Collins hardback 1st edition, 1981 (© Gerald Durrell/HarperCollins)

The Mockery Bird

by Gerald Durrell – Collins hardback 1st edition, 1981 (© Gerald Durrell/HarperCollins)THE MOCKERY BIRD – Gerald Durrell (Collins: London, 1981)

Book blurb: Peter Foxglove is sent to the island of Zenkali, a small British colony, as an assistant to the native King's (or, as he prefers to call himself, Kingy's) advisor. After meeting the many eccentric inhabitants of the island, he discovers that a thought-to-be-extinct bird, the Mockery Bird, worshipped as a deity by the island's native Fangoua tribe, is not so extinct after all. But the valley where the bird lives is about to be flooded to build a dam to provide energy for Zenkali's airport, and Peter and his friends need to stop this plan to save the bird.

ShukerNature comments: Gerald Durrell's non-fiction books documenting his family life and formative years as a young naturalist on the Greek island of Corfu, his many subsequent animal-collecting expeditions, and the establishment of his celebrated conservation-based zoo on Jersey are famous worldwide (My Family and Other Animals, The Bafut Beagles, Three Singles To Adventure, The Drunken Forest, Menagerie Manor – and many more), but it is not so well known that he has also written several excellent works of fiction, of which The Mockery Bird is a first-class example – slyly satirical, deftly incorporating a range of environmental and conservation issues, and, like all of his works, truly hilarious. Its avian star is a goose-sized, flightless species sporting blue plumage, long legs, and a large hornbill-like beak that bears a large hump in the male but only a small bony shield in the female. It earns its name from its call, which resembles loud mocking laughter.

The Turquoise Dragon

by David Rains Wallace – The Bodley Head hardback 1st edition, 1985 (© David Rains Wallace/The Bodley Head)

The Turquoise Dragon

by David Rains Wallace – The Bodley Head hardback 1st edition, 1985 (© David Rains Wallace/The Bodley Head)THE TURQUOISE DRAGON – David Rains Wallace (The Bodley Head: London, 1985)

Book blurb: 'I kicked my way to the shallows, stood up, and lifted from the water a creature that seemed made of turquoise and lapis lazuli, with ruby belly and topaz eyes. It was shaped more or less like a salamander, but it wasn't any species I'd seen...'The Turquoise Dragon is a fast-paced adventure thriller with an ecological twist. George Kilgore, a forester living quietly in the foothills of California's rugged Klamath Mountains, stumbles into a deadly web of intrigue when he discovers the body of a murdered biologist friend. With the uncomfortable feeling that homicide investigators have put him at the top of their list of suspects, Kilgore reluctantly begins his own investigation, compelled first by horror and then by growing curiosity.David Rains Wallace has already been widely acclaimed as an award-winning nature writer and now, with The Turquoise Dragon, he has made an auspicious fiction debut. He skilfully interweaves deft prose, a highly individual storyline involving collectors of endangered species, cocaine-dealers and the exotic location of the Klamath mountain range, with a deep understanding of the wilderness.

ShukerNature comments: Although no turquoise-blue, ruby-red salamanders have been reported there in real life, the Klamath Mountains include the Trinity Alps – which are famous among crypto-herpetologists as the reported home of an alleged undescribed species of giant salamander. This mystery beast was famously sought, albeit unsuccessfully, by the millionaire crypto-enthusiast Tom Slick, but during the expedition an elderly local man was interviewed who claimed that in his youth he had seen several salamanders as big as alligators on the shore of a lake there.

Brother Esau

by Douglas Orgill and John Gribbin – Sphere paperback edition, 1983 (©Douglas Orgill and John Gribbin/Sphere Books)

Brother Esau

by Douglas Orgill and John Gribbin – Sphere paperback edition, 1983 (©Douglas Orgill and John Gribbin/Sphere Books)BROTHER ESAU – Douglas Orgill and John Gribbin (The Bodley Head: London, 1982)

Book blurb: Turned towards them, seen more and more clearly as the flare sank towards the ground, was a face. In the bluish light the teeth seemed to be bared. The face was broad and hairy with a flattened nose, and heavy brow-ridges. The reddish hair which fringed it grew thickly round the large ears and head. As the light from the slowly sinking flare became more intense Harry saw that the desperate eyes were fixed on his. For a moment an extraordinary sense of urgent communication filled his mind...It was something like a gorilla, something like a man covered in hair. It was hard to estimate height while the creature was still crouched in the shadows, but it was probably around six feet. The body was barrel shaped, squat and obviously powerful...The Earth does not belong to man alone. The Himalayas bury their secrets well. Two skulls unearthed in the cradle of the human race — the remote heights of Kashmir — throw evolutionary theory into chaos. But a far more disturbing secret lies hidden deep in the bleak mountains and snow-swept valleys unseen by human eves.A few miles from the explosive triangle of tension where Afghanistan and Pakistan border on India the story of the century breaks. And the echoes of the most shattering revelation yet made to man threaten to plunge the world into total war which will turn the cradle of the human race into its final grave.

ShukerNature comments: This was the first cryptozoology novel with a man-beast theme that I ever read, and it remains one of my favourites. Its title derives directly from the Biblical account of Jacob and his twin brother Esau, who was hairy all over. Some cryptozoologists believe that this story is evidence for the existence of two separate human species – our own Homo sapiens and a distinct, hirsute species traditionally referred to as the wildman.

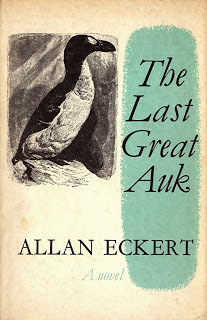

The Last Great Auk

by Allan Eckert – Collins hardback 1stedition, 1964 (© Allan Eckert/HarperCollins)

The Last Great Auk

by Allan Eckert – Collins hardback 1stedition, 1964 (© Allan Eckert/HarperCollins)THE LAST GREAK AUK – Allan Eckert (Collins: London, 1964)

Book blurb: Eddey Island loomed ahead of them like a gigantic red iceberg jutting from the frigid grey waters of the North Atlantic. Dimly in the haze behind it the swimmers could see the desolate coastline of south-western Iceland…There were more than eighty birds in this flock, and they spread out haphazardly in loose clusters which trailed behind the lead bird to a distance of nearly half a mile. The great auks had come home.The great auks were handsome penguin-like birds with head, neck, back and wings a deep glossy black, and underside a startling white. With tiny wings, they were the only flightless birds of the North Atlantic, but with their powerful legs and large webbed feet they swam and fished wonderfully.Mr Eckert has reconstructed with great skill and compassion the story of the great auks' last annual migrations between Eldey Island where they bred, off southwest Iceland, and South Carolina where they wintered. Each journey meant an almost incredible swim of three thousand miles. On the island and along the migration route lurked many perils—storms, killer-whales, fish-hooks, scientists, and worst of all, the murderous onslaught of feather and meat hunters. The story is that of the last of these birds, from his hatching and his adventures as a fledgling until as leader of the dwindling flock he returns to Eldey for the last time. By then the reader is hoping against what he knows is inevitable, against what did happen on June 3rd, 1844. The species became extinct. One species out of 8,000—does it matter? It does, and no reader of this sad and beautiful novel will forget it.

ShukerNature comments: Whereas its flightless feathered subject is itself neither strictly cryptozoological nor out-of-place, this novel is so remarkable a work that it definitely deserves to be read by as wide and as numerous an audience as possible, its poignant story a terrifying reminder of what has happened – and is still happening – to so many extraordinary animals at the hand, rifle, machete, chainsaw, and introduced livestock of humankind. Moreover, and where this novel is definitely pertinent to cryptozoology, the grim prospect of losing remarkable animal species to extinction before science has even confirmed their existence still lingers and overshadows conservation efforts like a dark, brooding wraith – one that can only be dispelled forever if future generations read books like this one, and take heed of its message.

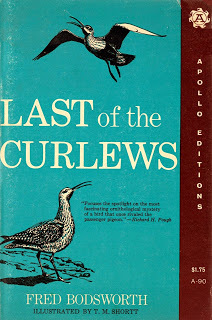

Last of the Curlews

by Fred Bodsworth – Dodd, Mead paperback edition, 1955 – another, more famous novel dealing with a once-common species (this time the eskimo curlew Numenius borealis) now confronting seemingly-inevitable extinction (© Fred Bodsworth/Dodd, Mead & Company)

Last of the Curlews

by Fred Bodsworth – Dodd, Mead paperback edition, 1955 – another, more famous novel dealing with a once-common species (this time the eskimo curlew Numenius borealis) now confronting seemingly-inevitable extinction (© Fred Bodsworth/Dodd, Mead & Company)

Published on May 13, 2015 21:53

May 8, 2015

TAPIRS AND TIGELBOATS – DOES THE MALAYAN TAPIR STILL EXIST IN BORNEO?

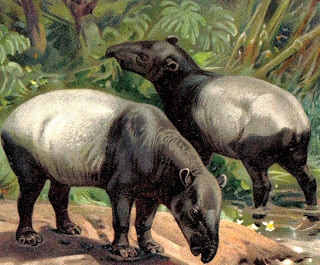

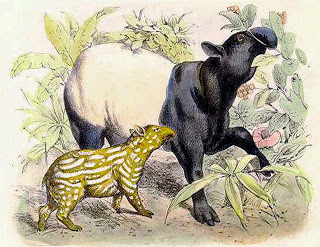

Malayan tapirs, depicted in a handsome chromolithograph from 1903 (public domain)

Malayan tapirs, depicted in a handsome chromolithograph from 1903 (public domain)Of the five modern-day species of tapir, four occur only in the New World and are uniformly dark brown/black in colour, whereas the fifth, the Malayan tapir Tapirus indicus, is an Old World speciality and is further differentiated by virtue of its 'saddle' - an area of striking white fur encompassing much of its torso and haunches (however, click here to check out a rare, all-black variant, known as Brevet's black tapir). Already known to exist in mainland Malaysia, Burma (Myanmar), Thailand, and the large Indonesian island of Sumatra, there is a good chance that this species' current distribution extends even further afield - onto the island of Borneo, where it supposedly died out only a few millennia ago during the Holocene, fossil remains having been found during cave excavations in the Borneo-situated Malaysian states of Sarawak and Sabah.

Over the years, a number of unconfirmed reports of tapirs existing in this extremely large yet still little-explored tropical island have been briefly documented in the literature, but these have incited conflicting opinions. Whereas, for instance, L.F. de Beaufort accordingly included Borneo within the accepted distribution range for T. indicus, Eric Mjöberg adopted a more circumspect stance, stating: "It is not yet certain that the tapir has been met with in Borneo, although there are persistent reports that an animal of its size and appearance exists in the interior of the country".

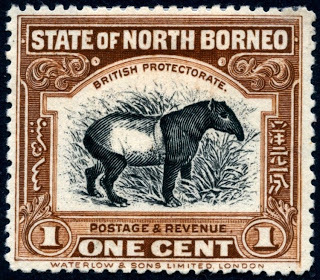

In 1949, however, Dr Tom Harrisson, then Curator of the Sarawak Museum, reported that tapirs were spied in Brunei (a small independent sultanate in Borneo) on two separate occasions some years earlier by Brunei resident E.E.F. Pretty, and he believed that the existence of such creatures in Borneo might yet be officially confirmed. Curiously, the Malayan tapir was featured on a 1909 postage stamp in a series issued by what was then North Borneo (now the Malaysian state of Sabah) that depicted species of animals supposedly native to this island. Wishful thinking perhaps - or an affirmation of reliable local knowledge that deserves formal acceptance by science?

The North Borneopostage stamp issued in 1909 that depicts a Malayan tapir (public domain)

The North Borneopostage stamp issued in 1909 that depicts a Malayan tapir (public domain)When investigating the pedigree of any cryptozoological creature, we must always consider the possibility that the eyewitness reports ostensibly substantiating its existence are in truth nothing more than misidentifications of one or more species already known to science. In the case of Borneo's tapir, however, there is only one such species with which it might be confused - the Bornean bearded pig Sus barbatus. This beast possesses not only a long snout, but also a distinctly pale 'saddle' over its back and haunches.

Even so, with a total head-and-body length of 3.5-5.5 ft, a body height not exceeding 3 ft, and a weight of 330 lb, it falls far short of the Malayan tapir's stature - as the head-and-body length of this latter species (the largest of all modern-day tapirs) can exceed 8 ft, its shoulder height can reach 42 in, and its weight can typically be as much as 800 lb (but with certain exceptional specimens having weighed up to 1190 lb). Nor could the bearded pig be mistaken for immature tapirs that have not attained their full size - because just like those of the four American species, juvenile Malayan tapirs are striped, only acquiring their characteristic white-backed, unstriped appearance when adult.

In short, the bearded pig cannot be contemplated as a likely identity of supposed tapirs encountered in Borneo, but it does offer one item of interest with regard to this subject. Its distribution corresponds almost precisely with that of the Malayan tapir, except for one major difference - the bearded pig is known to exist on Borneo. Yet until near-Recent times during the present Holocene epoch, the Malayan tapir was known to occur here too (thereby greatly reducing the likelihood that any tapir living on this island today could belong to an unknown species). If the bearded pig could persist into the present day on Borneo, why not the tapir too? The island is more than sufficiently spacious to house a very respectable number of tapirs, and their ecological requirements are more than adequately catered for. Indeed, the absence of the Malayan tapir from Borneo is really far more of a mystery than its disputed existence there!

Bearded pig (public domain)

Bearded pig (public domain)Ironically, it is very likely that the Malayan tapir's modern-day occurrence in Borneo would have been fully verified by now had it not been for an appalling instance of investigative apathy on the part of the scientific community not so long ago, which led to the disappearance of what seems to have been conclusive evidence for this species' persistence there. In November 1975, as recorded soon afterwards by Jan-Ove Sundberg in Pursuit, the Antara News Agency of Indonesia reported the capture in Kalimantan (Indonesian Borneo) of an extraordinary creature that appeared (at least from the description given of it) to be an impossible hybrid of several radically different types of animal.

According to the report (and always assuming, of course, that this entire episode was not a fabrication or a dramatic distortion of some much more commonplace event), the captured creature's body was similar to that of a tiger, its neck resembled that of a lion, it had an elephant-like trunk and the ears of a cow, its legs recalled those of a goat but its feet had chicken-like claws, and it reputedly sported a goatee beard like a billy goat's. Emphasising its composite appearance, the news agency referred to this amalgamated animal as a 'tigelboat' - a portmanteau word presumably derived from 'TIGEr', 'Lion', 'Bird', and 'gOAT'.

In spite of its bizarre appearance (or because of it?), the 'tigelboat' apparently failed to elicit any interest from scientists - which is a tragedy. If only someone had taken the trouble to analyse its description methodically, a major zoological discovery might well have been made - for as I have shown in various of my writings, when considered carefully it can be readily translated to reveal a creature that can be identified after all.

Chromolithograph from 1864 depicting an adult Malayan tapir and its striped offspring (public domain)

Chromolithograph from 1864 depicting an adult Malayan tapir and its striped offspring (public domain)Let us examine the features of the 'tigelboat' one at a time. If its body was similar to a tiger's, this must surely mean that it was striped. Equally, as the most noticeable aspect of a lion's neck is its mane, the tigelboat probably had a mane or a ridge of hair along its neck. An elephant-like trunk implies the presence of an elongated snout and upper lip, and cow-like ears would be relatively large and ovoid. If its legs recalled a goat's, then they must have been fairly long and sturdy (but not massively constructed), and chicken-like claws could be interpreted either as claws like those of certain mammalian carnivores or as distinctive, pointed hooves. As for its goatee, this might been merely a tuft of hair on its chin.

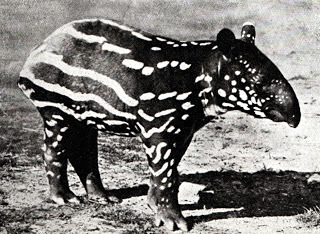

The tigelboat is an impossible hybrid no longer. Combine most of the translated features noted above, and the result is a description that can now be seen to portray very accurately a particular creature already familiar to science - a juvenile tapir. As already noted, unlike the adult the juvenile tapir is striped. Moreover, its ears are certainly large and ovoid, its limbs fairly long and sturdy but not massive, its hooves distinctive and pointed, and its snout and upper lip drawn out into a conspicuous proboscis or trunk.

Juvenile Malayan tapir, clearly possessing the tigelboat's most notable characteristics (public domain)

Juvenile Malayan tapir, clearly possessing the tigelboat's most notable characteristics (public domain)It is true, of course, that whereas its three New World relatives are maned, the Malayan tapir normally lacks any notable extent of hair upon its neck (though juveniles are somewhat hairier than adult); equally, it is not bearded. However, during its existence upon the island of Borneo for 10,000 years since the end of the Pleistocene, totally separated from all other populations of T. indicuselsewhere in Asia, it is probable that a Bornean contingent of Malayan tapirs would evolve one or two morphological idiosyncrasies (just as isolated populations of many other widely distributed animal species have done). Nothing very spectacular, but enough to permit differentiation from all other T. indicus specimens; such features could readily include a mane or a beard or both.

Certainly, in view of the otherwise impressive correspondence between the tigelboat and a juvenile tapir, the mere presence of a mane and beard is much too insignificant morphologically to challenge the identification of the former beast as the latter one.

The capture in Borneo of what was assuredly a young Malayan tapir should have attracted attention from zoologists, especially as the animal was maintained alive for a time at a prison in Tengarong. Tragically, however, it received no attention at all, and eventually it 'disappeared' - the fate of so many mystery beasts. No further news has emerged regarding this monumentally missed opportunity, and the whereabouts of the tigelboat's remains are unknown - so there is no skeleton or skull available for identification, let alone the living animal itself. Not even a photograph of it has turned up, and so the Bornean tapir is still a non-existent member of this island's fauna - at least as far as official records are concerned.

Malayan tapir (© Fritz Geller-Grimm/Wikipedia)

Malayan tapir (© Fritz Geller-Grimm/Wikipedia)Even so, there is still hope that its existence will be confirmed one day. Borneo is a huge island, with extensive, little-penetrated rainforests and swamplands - ideal territory for secretive tapirs. And for absolute proof that large beasts can remain undetected here, look no further than the Sumatran rhinoceros Dicerorhinus sumatrensis, deemed extinct in Sarawak from the early 1940s - until a herd was found in a remote Sarawak valley in 1984.

If rhinos can exist unknown to science in parts of Borneo, how much greater is the likelihood that the smaller, well-camouflaged Malayan tapir can elude discovery there too?

This ShukerNature blog post is excerpted and updated from my book In Search of Prehistoric Survivors .

Published on May 08, 2015 20:16

May 7, 2015

A GIANT HYRAX AND CHINA'S MYSTERY BEASTS OF BRONZE

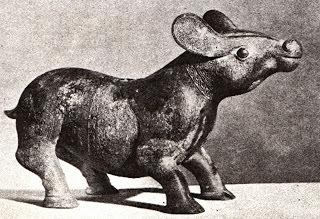

H.J. Oppenheim's bronze Chinese sculpture of a mysterious beast resembling a giant hyrax (public domain)

H.J. Oppenheim's bronze Chinese sculpture of a mysterious beast resembling a giant hyrax (public domain)On 30 November 1935, a British magazine called The Field published an article by F. Martin Duncan entitled 'A Chinese Noah's Ark', which surveyed a selection of Chinese works of art from an exhibition that was being staged by London's Royal Academy. Duncan's article included photographs of several exhibits - one of which (its photo opening this present ShukerNature article) was a small bronze statuette of an exceedingly strange animal.

The statuette was owned at that time by H.J. Oppenheim, and as can be seen here, the creature that it portrays bears little resemblance to any modern-day species - which presumably explains why it was referred to in the exhibition as a mythical animal. Overlooked by cryptozoology, moreover, the bronze was soon forgotten beyond the perimeters of the art world. Today, it is housed in the collections of the British Museum, London, to whom it was bequeathed in 1947 by Oppenheim.

During the early 1980s, however, an article in the magazine Smithsonian concerning the Warring States period in China (480-222 BC) included a photograph of a near-identical bronze statuette. It was one of 151 items in an exhibition of Chinese art from the Warring States Period on display at the Smithsonian Institution's Freer Gallery of Art. Several of these statuettes had been found in 1923 near the village of Li-yu, in the Shanxi province.

This time, the animal was called a "fanciful tapirlike beast" (despite the fact that it looks nothing like a tapir!), with the comment that it seemed to have no practical or ritual function. Not long afterwards, Brown University ungulate expert Dr Christine Janis serendipitously came upon the article - while browsing through some magazines in her doctor's waiting room! (And during the mid-1980s I sent her a copy of the photograph from The Field article.) Moreover, while visiting Sydney, Australia, she was able to purchase a life-sized replica of one of these bronze beast statuettes – possibly of the Freer specimen as it closely resembles this particular one, and the Freer Gallery has indeed made available for purchasing purposes an official replica of theirs, produced by New York's Alva Studios.

Christine's replica specimen of one of the bronze Chinese mystery beast statuettes (© Dr Christine Janis)

Christine's replica specimen of one of the bronze Chinese mystery beast statuettes (© Dr Christine Janis)A photograph of the original Freer statuette can be accessed on this gallery's official website (click here ). It is stated there to be from the Middle Eastern Zhou dynasty (existing during the Warring States Period), and, more specifically, to date from the early 5th Century BC. Its dimensions are given as: height, 11.2 cm; length, 18.3 cm; diameter, 6.3 cm. The following details are also included:

"This quadruped was crafted with considerable detail, especially in the modeling of the animal's face, its short, hoofed legs, and its scaled rotund body. Despite the clear features, the identity of the animal remains obscure, as does the precise function of the bronze figure. The collar of cowrie shells, twisted rope bands, striations, and scale patterns suggest that this animal was also produced in the Houma workshops in southern Shanxi Province."

Christine had no problem in classifying its mysterious 'tapir' - due not only to her specialised knowledge of ungulates, but also to the fact that she had actually kept smaller versions as pets.

Rock hyrax Procavia capensis (© Chris 73/Wikipedia)

Rock hyrax Procavia capensis (© Chris 73/Wikipedia)The beast of the bronzes was a hyrax - one of those superficially rabbit-like creatures also termed conies or dassies, but supplied with small hooves and an anatomy that unmasks them as diminutive relatives of the proboscideans (elephants, mammoths, and mastodonts). However, this particular example appeared to be far from diminutive.

Indeed, as she subsequently explained in a paper published in 1987 by the now-defunct International Society of Cryptozoology's scientific journal, Cryptozoology, Christine became convinced that it was meant to represent a certain giant form of hyrax from China's late Pliocene (and possibly early Pleistocene too). This pig-sized creature was Pliohyrax, currently known to have been represented by at least three different species. If Christine is correct, then Pliohyraxmust have persisted into historic times. (Incidentally, there were some even bigger, earlier species of hyrax, belonging to the aptly-named genus Titanohyrax, that are estimated to have been as big as rhinoceroses!)

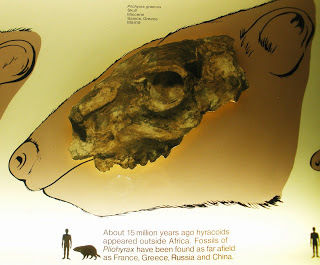

Fossil skull portion of Pliohyrax graecus (© Ghedoghedo/Wikipedia)

Fossil skull portion of Pliohyrax graecus (© Ghedoghedo/Wikipedia)The head of the bronze beasts closely compares to those of modern-day species of hyrax - and so did that of Pliohyrax. In contrast, their body is hippopotamus-like - but although no post-cranial remains of Pliohyrax are presently known, Christine noted that the high position of the eye sockets in its skull (comparable to those of the hippo) indicates that it might have been semi-aquatic like the hippo. It may therefore have possessed a similar body shape too, as fossil ungulates with hippo-shaped bodies tend to have these elevated eyes.

Nevertheless, there was one notable problem when attempting to reconcile the bronze beasts with any type of hyrax - whereas the latter have several hooves on each foot, the feet of the bronze beasts have only one hoof apiece. Christine, however, has proposed that this discrepancy indicates that the animal was one known from mythology rather than one personally seen by the sculptor. Presumably, therefore, the giant hyrax had indeed survived long beyond the Pliocene, and had once been well-known to mankind in China, becoming incorporated into their mythology, but had died out prior to the Warring States Period.

There is also an equally plausible alternative to this possibility, as proffered once again by Christine. A hyrax the size of Pliohyrax would be much heavier than today's notably smaller species, and may therefore have evolved a more compact type of foot structure with a pad underlying the foot - resembling the feet of pigs and hippos. Perhaps this is what the sculptor was attempting to convey when producing the bronze statuettes - hence Pliohyrax may have lingered into the Warring States Period after all. As there is no evidence of its survival today, however, we must assume that it subsequently became extinct - or perhaps, like many other large, sluggish, inoffensive beasts with succulent flesh, it was exterminated by hunters.

Front view of Christine's replica statuette (© Dr Christine Janis)

Front view of Christine's replica statuette (© Dr Christine Janis)Finally: While researching this fascinating subject, I discovered a beautiful life-sized replica of the Freer Gallery's bronze beast statuette on the website of an auction house called Invaluable. Produced by Alva Studios, the statuette was sold on 28 September 2013 for US$ 100, but its listing remains on the auction house's site (click here ). In addition to the description of the original statuette given in the Freer gallery, Invaluable's listing also includes the following details:

"Losses to the ears on this replica piece. Labeled 'Authentic Copyrighted Replica Made From the Original At the Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, By Alva Studios, Inc., New York'."

Its listing contains several photographs too, including this one:

Official replica of the Freer Gallery's bronze giant hyrax-like statuette, sold by Invaluable in 2013 (© Invaluable)

Official replica of the Freer Gallery's bronze giant hyrax-like statuette, sold by Invaluable in 2013 (© Invaluable)This ShukerNature blog article is a greatly-expanded, updated excerpt from my book In Search of Prehistoric Survivors .

Published on May 07, 2015 21:26

May 4, 2015

FROM DEVILISH GECKO TO DERIVED DRAGONET - YET ANOTHER PHOTO-MANIPULATED METAMORPHOSIS

The deceptive 'dragonet' photo doing the rounds online (photo-manipulation originator unknown).

The deceptive 'dragonet' photo doing the rounds online (photo-manipulation originator unknown).The photograph opening this present ShukerNature blog article has been brought to my attention on numerous occasions with requests as to whether the animal that it depicts is real.

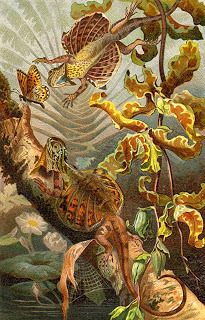

Some have wondered whether it may be a species of flying dragon Draco sp. – i.e. one of those famous little agamid lizards (up to 8 inlong) native to southeastern Asia whose greatly elongated ribs are connected to one another on each side of its body by a wing-like membrane that enables the creature to glide passively (though not actively fly) through the air after leaping from the trunk or branch of a tree.

Beautiful 19th-Century engraving of flying dragons Draco volans (public domain)

Beautiful 19th-Century engraving of flying dragons Draco volans (public domain)I have even received enquiries as to whether this photograph was of a real species of dragon, or, alternatively, some gliding lizard-like reptile that had mysteriously survived from prehistoric times into the present day. None of these options is correct, of course, though there were indeed at least three notable and very different types of gliding lizard-like reptile alive at one time or another in the ancient world.

Although unrelated to the modern-day Dracoagamids, Kuehneosaurus latus was outwardly similar, inasmuch as it too possessed wing-like gliding membranes consisting of elongated ribs interconnected on each side by a membrane. However, recent aerodynamic studies indicate that it used these 'wings' not for gliding but rather for parachuting. Up to 2.3 ft long, this species was formally described and named in 1962 by P.L. Robinson, and existed in southwest England during the late Triassic Period, around 237-201 million years ago.

So too did a much longer-'winged' relative, Kuehneosuchus latissimus, also formally described in 1967 by Robinson, although some researchers have suggested that this latter species may simply have been a sexual morph of Kuehneosaurus, but adapted for true gliding rather than merely parachuting. These two species (if indeed they are separate species) are the only members of the taxonomic family Kuehneosauridae, which is housed within a long-extinct order of archaic reptiles known as eolacertilians or dawn lizards.

Restoration of Kuehneosuchus latissimus (left) and Kuehneosaurus latus (right) in life (© Nobu Tamura-Wikipedia)

Restoration of Kuehneosuchus latissimus (left) and Kuehneosaurus latus (right) in life (© Nobu Tamura-Wikipedia)A second type of prehistoric lizard-like glider but fundamentally different from any other currently known to science was Coelurosauravus, a genus of basal diapsid reptile containing two species – C. elivensis (described in 1928) and C. jaekeli (described in 1930). Around 16 in long in total length, these also possessed a pair of wing-like gliding membranes, but the membranes' struts were not elongated ribs. Instead, they were lengthy rod-like structures constituting newly-evolved dermal bones, unique to this reptilian genus.

The two species variously lived in what is now England, Germany, and Madagascar during the late Permian Period, approximately 260-250 million years ago. Fans of the science-fiction television series Primevalwill know that the aerial reptile kept by the team as a pet and named Rex is a Coelurosauravus, though Rex is much bigger than known specimens, and is also capable of active, powered flight, whereas real Coelurosauravus species could only glide passively.

Restoration of Coelurosauravus jaekeli, from Germany (© Nobu Tamura-Wikipedia)

Restoration of Coelurosauravus jaekeli, from Germany (© Nobu Tamura-Wikipedia)Very different again was a third type of prehistoric gliding lizard-lookalike – Sharovipteryx mirabilis, formally described in 1971 and known only from its holotype, which had been discovered in 1965 inthe Madygen Formation, Dzailauchou, on the southwest edge of the Fergana valley in what is now the independent Asian country of Kyrgyzstan. It dates from the middle-late Triassic Period, approximately 225 million years ago.

What makes this species so distinctive is that unlike all other reptilian gliders, its gliding membranes surrounded its pelvic girdle. It belonged to the taxonomic order Protorosauria.

Restoration of Sharovipteryx mirabilis (© Dmitry Bogdanov-Wikipedia)

Restoration of Sharovipteryx mirabilis (© Dmitry Bogdanov-Wikipedia)But as the dragonet in the photograph opening this ShukerNature article is none of these creatures, what exactly is it?

In fact, it is a gecko, but not one that has ever been breathed into life by either Mother Nature or evolution. Its species is the satanic leaf-tailed gecko Uroplatus phantasticus, named after its somewhat devilish, fantastical appearance and its leaf-like tail. Formally described in 1888 by prolific English zoologist George A. Boulenger, and indigenous to Madagascar, it is the smallest species of leaf-tailed gecko within the genus Uroplatus, measuring only 2.6-6 in long in total length.

Needless to say, however, although it is certainly very eyecatching morphologically, this does not extend to its possessing wings. When I saw the dragonet photograph a while back, I recognised straight away that it was merely a novel photo-manipulation of some original photograph of U. phantasticus. Consequently, it did not take long for me to uncover the latter online, which turned out to have been been snapped by Piotr Naskrecki. And here it is, alongside its derived dragonet:

The original Uroplatus phantasticus gecko photograph (left) and the dragonet image derived from it via photo-manipulation (right) (© Piotr Naskrecki/photo-manipulation originator unknown)

The original Uroplatus phantasticus gecko photograph (left) and the dragonet image derived from it via photo-manipulation (right) (© Piotr Naskrecki/photo-manipulation originator unknown)Another longstanding internet hoax picture is duly unmasked, though whoever is responsible for creating it from the gecko photograph remains unidentified.

My thanks to Facebook friend Carl Kelsall for most recently bringing the dragonet photograph to my attention and, in so doing, inspiring me to pen this exposé.

Rex from Primeval (© ITV Studios/ProSieben/Impossible Pictures/Treasure Entertainment/M6 Films)

Rex from Primeval (© ITV Studios/ProSieben/Impossible Pictures/Treasure Entertainment/M6 Films)

Published on May 04, 2015 20:26

May 2, 2015

HORNING IN ON INDONESIA'S SCALY RHINOCEROSES

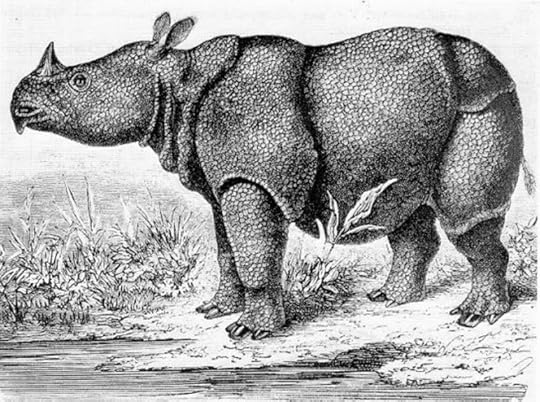

Chromolithograph of a female Javan rhinoceros imported by London-based animal dealer Charles Jamrach from the Sunderbans in India to London Zoo, where, sadly, it only lived for just under 6 months in 1877 (public domain)

Chromolithograph of a female Javan rhinoceros imported by London-based animal dealer Charles Jamrach from the Sunderbans in India to London Zoo, where, sadly, it only lived for just under 6 months in 1877 (public domain)In 1941, Willy Ley noted in his book The Lungfish and the Unicorn that at some stage during the middle portion of the 1920s, a Dr P. Vageler - regularly contacted by zoos wishing to replenish their animal collections - was seeking some specimens of the Asian rhinos when he met up with J.C. Hazewinkel, a noted big game hunter. After learning that Vageler required new rhinoceroses, Hazewinkel showed him some photos of eight that he had shot in Sumatra, and which appeared to be new in every sense of the word. For the type that they represented — although familiar to the natives, who called it 'badak tanggiling'(translated as 'scaly rhinoceros') - seemed to differ greatly from the form familiar to Vageler on Sumatra.

Unlike the known, two-horned Sumatran rhinoceros Dicerorhinus sumatrensis, the badak tanggiling bore just a single horn. If this had been the only difference, it could have been explained as a mere freak of nature. However, Hazewinkel stated that the female badak tanggiling was often totally hornless, and that the form as a whole had scaly armour and attained a length of 10 ft. In contrast, the female Sumatran rhinoceros is rarely if ever hornless, and the species as a whole is hairy rather than scaly and only attains a length of 8—9 ft.

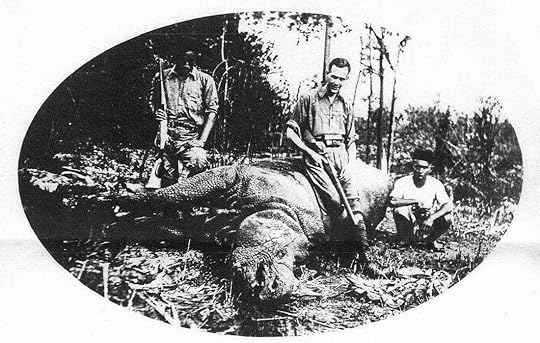

J.C. Hazewinkel posing on the carcase of the first in the series of Javan rhinoceroses shot by him in Sumatra(public domain)

J.C. Hazewinkel posing on the carcase of the first in the series of Javan rhinoceroses shot by him in Sumatra(public domain)As Dr Vageler readily recognized, the Sumatran rhino thus became an unlikely candidate for the badak tanggiling’s identity. In his coverage of this episode, Willy Ley stated that Hazewinkel’s photos convinced Vageler that a second species of rhinoceros existed on Sumatra, and that in reply to his requests Vageler was promised living specimens of it to send on to various zoos worldwide, but they never arrived. Ley concluded his account by stating that the badak tanggilingtherefore remains a shadow in our zoological encyclopedias, but: “...it may, however, be rediscovered almost any day”.

From all of this it would seem that Ley considered the badak tanggiling to be a wholly unknown, undescribed species. In fact, its identity is surely no mystery, for this enigmatic creature is clearly Rhinoceros sondaicus, the Javan rhinoceros. Not only is it of comparable size to the badak tanggiling, has characteristically scaly armour, and is a one-horned species whose females are indeed sometimes hornless, but at the time of Vageler and Hazewinkel it did exist on Sumatra (but this was not widely known outside scientific circles). Indeed, the last known Sumatran specimens of the Javan rhino did not die until World War II.

The first one-horned rhinoceros shot in Sumatraby J.C. Hazewinkel (public domain)

The first one-horned rhinoceros shot in Sumatraby J.C. Hazewinkel (public domain)There is a further, more specific, piece of evidence confirming this identification. On 23 December 1933, the Illustrated London News published an article by Hazewinkel, in which he described his pursuit and shooting of the first of eight specimens of large, scaly, one-horned rhinoceros on Sumatra during the mid-1920s. The photos of the animal dispel any doubt as to its identity - one that Hazewinkel, moreover, freely announced. It was a Javan rhinoceros. Indeed, echoing the general unawareness concerning the existence of this species on Sumatra at that time, Hazewinkel had entitled his article ‘A One-Horned Javanese Rhinoceros Shot in Sumatra, Where It Was Not Thought to Exist’.

Close-up of the first Javan rhinoceros shot in Sumatraby J.C. Hazewinkel, revealing its distinctive scaly armour (public domain)

Close-up of the first Javan rhinoceros shot in Sumatraby J.C. Hazewinkel, revealing its distinctive scaly armour (public domain)Clearly, there can be no question that those eight Javan rhinos shot by Hazewinkel on Sumatra in the mid-1920s are one and the same as the eight Sumatran badak tanggiling shot by him and mentioned to Vageler by him during that same period. Moreover, as I discovered when researching this subject further, in 1926 Vageler actually published a short paper in Berliner Illustrirter Zeitung (plus two others a year later in Science News-Letter and Umschau) in which he formally described Sumatra's Javan rhinoceros merely as a new variety (not even a new subspecies) of the Javan rhinoceros, naming it Rhinoceros sundaicus [sic] var. sumatrensis.

Javan rhinoceros engraving from 1872, by Hermann Schlegel (public domain)

Javan rhinoceros engraving from 1872, by Hermann Schlegel (public domain)Evidently, therefore, in spite of Ley's apparent assumption to the contrary, Vageler did indeed recognise that Sumatra's one-horned rhinoceros belonged to the Javan rhinoceros's species, and was not a separate, hitherto-unknown species at all.

Captive Javan rhinoceros, probably in India, photographed in c.1900 (public domain)

Captive Javan rhinoceros, probably in India, photographed in c.1900 (public domain)According to Joseph Belmont, another animal collector for zoos, a mysterious beast known as the scaled rhinoceros allegedly existed amidst the inhospitable, fever-ridden swamps of Java. Writing in Catching Wild Beasts Alive (1931), Delmont reported that this cryptic creature, supposedly distinct from the known species of Javan rhinoceros, had only been shot twice, with no living specimen ever having been obtained.

However, as already revealed in this present ShukerNature blog article, the ‘armour’ of known species of Javan rhino is noticeably scale-like, quite different from that of its closest relative the great Indian rhinoceros Rhinoceros unicornis. Consequently, it would once again seem that the creature in question is Rhinoceros sondaicus after all.

Photograph of the Javan rhinoceros exhibited at London Zoo in 1877, in which its scale-like armour can be readily perceived (public domain)

Photograph of the Javan rhinoceros exhibited at London Zoo in 1877, in which its scale-like armour can be readily perceived (public domain)This ShukerNature blog post is excerpted and expanded from my books Extraordinary Animals Worldwide and Extraordinary Animals Revisited . Check them out for more accounts of mysterious and controversial forms of rhinoceros.

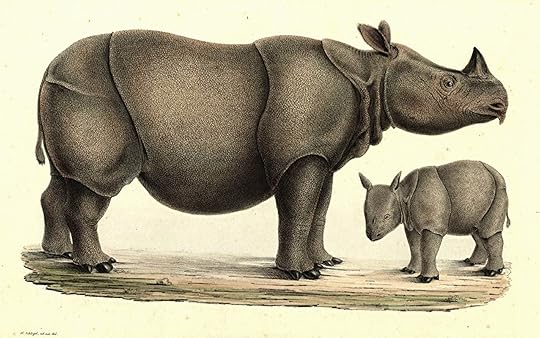

An adult Javan rhinoceros and calf, as depicted in a colour engraving from 1839 (public domain)

An adult Javan rhinoceros and calf, as depicted in a colour engraving from 1839 (public domain)

Published on May 02, 2015 20:39

May 1, 2015

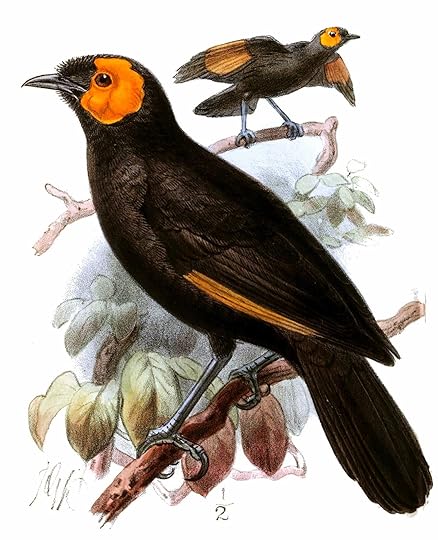

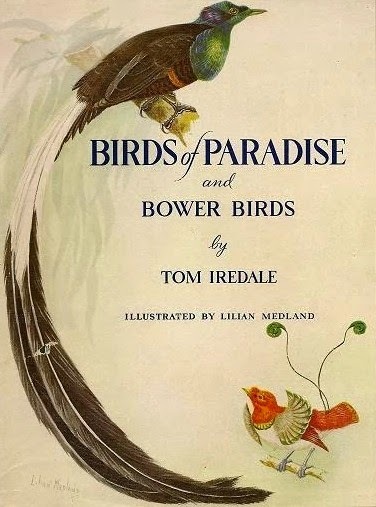

OUTING THE FALSE BIRDS OF PARADISE, INNING A COUPLE OF NOT-SO-FALSE ONES, AND REVIEWING SOME ONCE-AND-FUTURE(?) ONES

Late 19th-Century painting of an adult male King of Saxony bird of paradise (public domain)

Late 19th-Century painting of an adult male King of Saxony bird of paradise (public domain)There is no question whatsoever that the birds of paradise, a taxonomic family (Paradisaeidae) whose members are predominantly endemic to New Guinea but also name-check a few representative species inhabiting Australia and certain Indonesian islands, include among their number some of the world's most breathtakingly beautiful avian forms ever beheld by the eyes of humankind. In these species, the breeding plumage of the males erupt in a veritable explosion of feathered flamboyance – cascades of fiery streamers, ostentatious racquet-plumed head and pompom-plumed tail quills, an extravagant riot of ruffs, crests, tippets, lyrate extremities, and a glossy, scintillating, polychromatic surfacing of shimmering iridescence.

Moreover, so varied in form are the 40-odd species currently recognised by science that there has been much controversy down through the years regarding their comparative taxonomic affinities to one another, the possibility that certain rare preserved specimens are not mere hybrids as traditionally deemed but may represent species that are now extinct (click here for my ShukerNature blog post documenting these so-called 'lost birds of paradise'), and whether some species are not birds of paradise at all. It is with this last-mentioned, little-publicised category, the false birds of paradise, that this present ShukerNature blog post is concerned.

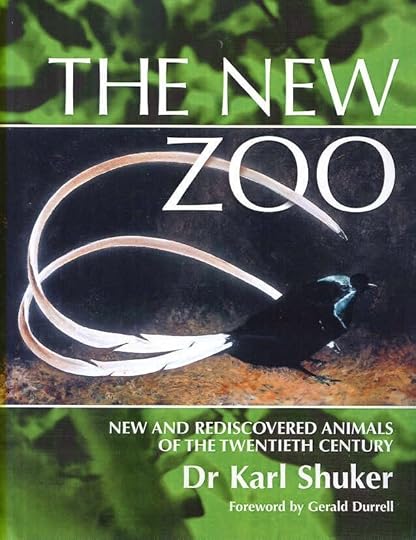

The most recent Paradisaeidae species to be accepted by science was the ribbon-tailed bird of paradise Astrapia mayeri, discovered to the west of Mount Hagen in New Guinea during 1938 and formally described a year later.

Errol Fuller's beautiful painting of a male ribbon-tailed bird of paradise (the female lacks this species' eponymous plumes) as featured on the front cover of my book The New Zoo: New and Rediscovered Animals of the Twentieth Century (© Errol Fuller/Dr Karl Shuker)

Errol Fuller's beautiful painting of a male ribbon-tailed bird of paradise (the female lacks this species' eponymous plumes) as featured on the front cover of my book The New Zoo: New and Rediscovered Animals of the Twentieth Century (© Errol Fuller/Dr Karl Shuker)Between then and the 21st Century, a total of either 43 or 45 Paradisaeidae species had generally been recognised by ornithologists (not everyone classified the growling riflebird Ptilornis intercedens and the bronze six-wired bird of paradise Parotia berlepschias full species). In February 2000, however, the publication of an extensive taxonomic study conducted upon this family's members by ornithological researchers Drs Joel Cracraft and Julie Feinstein, featuring mitochondrial gene analyses and morphological comparisons, provided some very startling surprises – exposing no less than four longstanding members as false birds of paradise. They have been since been duly evicted from Paradisaeidae and rehoused elsewhere.

19th-Century painting of a pair of Loria's satinbirds (male on left) by John Gould (public domain)

19th-Century painting of a pair of Loria's satinbirds (male on left) by John Gould (public domain)Three of these paradise-plumed pretenders constituted the former subfamily Cnemophilinae, whose trio of species had long been a source of ornithological contention as to whether their affinities did indeed lie with – or, more precisely, within – Paradisaeidae. Stripped of their 'bird of paradise' monikers, they are now referred to as satinbirds on account of their very soft plumage, and are known in full as: Loria's satinbird Cnemophilus loriae, the crested satinbird C. macgregorii, and the yellow-breasted or lobe-billed satinbird Loboparadisea lobata.

19th-Century painting of a pair of crested satinbirds (public domain)

19th-Century painting of a pair of crested satinbirds (public domain)The Cracraft/Feinstein study provided clear molecular and morphological evidence that these species were sufficiently discrete from all other birds of paradise for their entire subfamily to require recategorisation as a distinct taxonomic family in its own right – Cnemophilidae. It constitutes a basal family within the superfamily Corvoidea, alongside Paradisaeidae, Corvidae (the crows), and many other passerine families.

Painting of a yellow-breasted satinbird by John G. Keulemans, 1897 (public domain)

Painting of a yellow-breasted satinbird by John G. Keulemans, 1897 (public domain)As for the fourth false bird of paradise, Macgregoria pulchra, the only member of its genus and hitherto known as MacGregor's bird of paradise, which was formally described and named as far back as 1897, Cracraft and Feinstein had an even bigger shock in store. This was because their findings showed that it was not even a member of the superfamily Corvoidea, let alone the bird of paradise family Paradisaeidae. Instead, it was identified unequivocally as a honeyeater, i.e. belonging to the family Meliphagidae (whose numerous members occur widely across Australasia, the Pacific, and even into Bali), which in turn is housed within the superfamily Meliphagoidea.

Painting of MacGregor's honeyeater by John G. Keulemans, 1897 (public domain)

Painting of MacGregor's honeyeater by John G. Keulemans, 1897 (public domain)Having said that, I must confess that this latter taxonomic turnabout did not come as a major surprise to me because Macgregoria pulchra, now known as MacGregor's honeyeater, bears a very close external resemblance to two particular species of honeyeater – the common smoky honeyeater Melipotes fumigatus and the recently-discovered wattled smoky honeyeater Melipotes carolae, both of which, like Macgregoria, are native to New Guinea. Sometimes, of course, outward similarities are merely the result of convergent evolution rather than being indicative of close genetic affinity, but in this particular case their morphological resemblances were indeed mirrored by their genetic comparabilities.

Wattled smoky honeyeater (bottom left) depicted on an Indonesian postage stamp in my collection

Wattled smoky honeyeater (bottom left) depicted on an Indonesian postage stamp in my collectionAnd now for a couple of not-so-false birds of paradise.

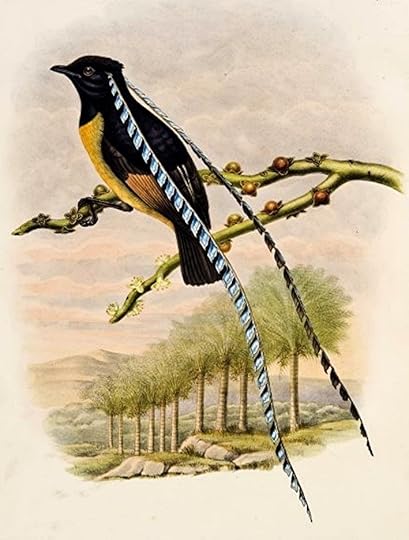

Of all the many spectacular, valid Paradisaeidae members in existence, my personal favourite is the truly extraordinary King of Saxony bird of paradise Pteridophora alberti, or, more specifically, the adult male of this species. Only the size of a starling, with predominantly black and yellow plumage, what sets it entirely apart from all other birds of paradise – and, indeed, all other birds of any kind – is the pair of enormously long, ribbon-like plumes born upon its head. Each one is more than twice the total length of the bird itself and resembles a great length of tiny enamelled scallops or mini-flags (earning its species the alternative name of enamelled bird), blue on one side and pink on the other. These two plumes are independently erectile, and during courtship the male variously directs them forwards over his head, downwards and forwards beneath his perch, backwards, and even directly away from one another horizontally in his enthusiastic semaphore-like attempts to attract and retain the attention of the much more sombre-looking female, who lacks these incredible plumes.

Taxiderm specimen of a male King of Saxony bird of paradise (with a taxiderm MacGregor's honeyeater behind it) at Tring Natural History Museum (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Taxiderm specimen of a male King of Saxony bird of paradise (with a taxiderm MacGregor's honeyeater behind it) at Tring Natural History Museum (© Dr Karl Shuker)Native to New Guinea, this marvellous species was formally described in December 1894 by Dresden Museum ornithologist Adolf B. Meyer, commemorating in both its common and binomial name King Albert of Saxony. However, when the first skins had been brought to Europe, they had been denounced as fakes due to the ostensible implausibility of the male's head plumes, and even after Meyer had recognised that they were genuine and accordingly described this species, not everyone was convinced about its authenticity.