Karl Shuker's Blog, page 35

September 3, 2015

CRYPTO-SELFIES! IN THE PICTURE WITH SOME SERIOUSLY WEIRD – BUT WONDERFUL – WILDLIFE

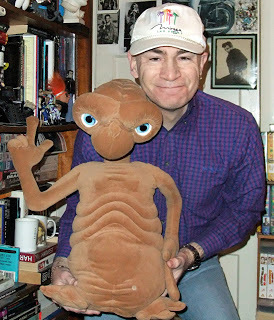

With E.T. – how could I not take pity on this errant extraterrestrial and bring him back home with me? In any case, he must be happy here – he hasn't phoned home once, which is just as well, bearing in mind the cost of intergalactic telephone calls these days! (© Dr Karl Shuker)

With E.T. – how could I not take pity on this errant extraterrestrial and bring him back home with me? In any case, he must be happy here – he hasn't phoned home once, which is just as well, bearing in mind the cost of intergalactic telephone calls these days! (© Dr Karl Shuker)Over the years, I've found myself sharing space in photographs – selfies, as they'd be called nowadays – with some exceedingly strange entities (and those are just my friends!). But seriously, browsing through my albums recently I came upon a considerable number featuring me alongside some truly weird – but indisputably wonderful – wildlife. So here, as one of my more light-hearted ShukerNature contributions, and the first of an occasional series, is a dozen of my most memorable crypto-selfies, annotated with a bountiful abundance of decidedly (ir)relevant information…

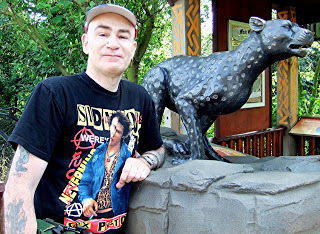

Alongside a black cheetah statue at Colchester Zoo, in Essex, England, which I visited in 2013; as noted in my books

Mystery Cats of the World

and

Cats of Magic, Mythology, and Mystery

, a few records of all-black (melanistic) cheetahs are indeed on file, including a specimen spied in the company of a normal cheetah by Lesley D.E.F. Vesey-Fitzgerald in Zambia during the first half of the 20thCentury, and another one sighted in Kenya's Trans-Nzoia District by H.F. Stoneham in 1925 (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Alongside a black cheetah statue at Colchester Zoo, in Essex, England, which I visited in 2013; as noted in my books

Mystery Cats of the World

and

Cats of Magic, Mythology, and Mystery

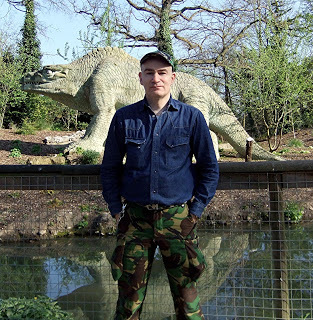

, a few records of all-black (melanistic) cheetahs are indeed on file, including a specimen spied in the company of a normal cheetah by Lesley D.E.F. Vesey-Fitzgerald in Zambia during the first half of the 20thCentury, and another one sighted in Kenya's Trans-Nzoia District by H.F. Stoneham in 1925 (© Dr Karl Shuker) With one of the famous 19th-Century dinosaur statues at Crystal Palace Park in Bromley, London, which I visited in 2009; created by famous sculptor Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins (1807-1894) and totally outdated now, this one is meant to be a Megalosaurus, but its reconstruction was guided by the popular yet erroneous belief current at that time that dinosaurs resembled giant lizards (© Dr Karl Shuker)

With one of the famous 19th-Century dinosaur statues at Crystal Palace Park in Bromley, London, which I visited in 2009; created by famous sculptor Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins (1807-1894) and totally outdated now, this one is meant to be a Megalosaurus, but its reconstruction was guided by the popular yet erroneous belief current at that time that dinosaurs resembled giant lizards (© Dr Karl Shuker) Holding a Brazilian were-pig skull – hailing from Rio de Janeiro, this is the skull of a wild boar that has been intricately decorated to resemble the supposed appearance of a Brazilian were-pig's head (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Holding a Brazilian were-pig skull – hailing from Rio de Janeiro, this is the skull of a wild boar that has been intricately decorated to resemble the supposed appearance of a Brazilian were-pig's head (© Dr Karl Shuker) At Drayton Manor Park and Zoo, in Staffordshire, England, standing somewhat warily alongside a disconcertingly life-like, life-sized replica of North America's late Pliocene/early Pleistocene terror bird Titanis walleri, which may have stood up to 8 ft tall – check out my book

The Menagerie of Marvels

for an extensive chapter documenting the history of these flightless but fleet-footed and sometimes truly gargantuan carnivorous birds (© Dr Karl Shuker)

At Drayton Manor Park and Zoo, in Staffordshire, England, standing somewhat warily alongside a disconcertingly life-like, life-sized replica of North America's late Pliocene/early Pleistocene terror bird Titanis walleri, which may have stood up to 8 ft tall – check out my book

The Menagerie of Marvels

for an extensive chapter documenting the history of these flightless but fleet-footed and sometimes truly gargantuan carnivorous birds (© Dr Karl Shuker) With an acklay – when I purchased this model at a market a few years ago, I had no idea what the creature was that it represented, but thanks to some knowledgeable sci-fi enthusiast friends on Facebook I soon learnt that it was an acklay, a huge non-sentient carnivore up to 11.5 ft tall, hailing from the planet Vendaxa in the Star Wars canon's universe (© Dr Karl Shuker)

With an acklay – when I purchased this model at a market a few years ago, I had no idea what the creature was that it represented, but thanks to some knowledgeable sci-fi enthusiast friends on Facebook I soon learnt that it was an acklay, a huge non-sentient carnivore up to 11.5 ft tall, hailing from the planet Vendaxa in the Star Wars canon's universe (© Dr Karl Shuker) Alongside a life-sized animatronic model of the feathered dinosaur Citipati at Bristol Zoo, England, in 2013; an oviraptorid theropod from Mongolia's Late Cretaceous period, Citipatiwas named after a pair of murdered meditating monks from Tibetan Buddhist folklore, it possessed a large toothless beak, and it stood as large as a present-day emu; in this particular reconstruction, it looks decidedly cassowary-like (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Alongside a life-sized animatronic model of the feathered dinosaur Citipati at Bristol Zoo, England, in 2013; an oviraptorid theropod from Mongolia's Late Cretaceous period, Citipatiwas named after a pair of murdered meditating monks from Tibetan Buddhist folklore, it possessed a large toothless beak, and it stood as large as a present-day emu; in this particular reconstruction, it looks decidedly cassowary-like (© Dr Karl Shuker) There I was, minding my own business walking round the small West Midlands, England, town of Cradley Heath, when, happening to step inside a sci-fi/comic shop, who should I encounter there but the Predator! I can only assume that my trusty leather biker jacket helped to conceal me from its thermal imaging capability long enough for me to get this photo snapped of me alongside it; if you're wondering why the photo is a little blurry, it's because the (ex) person taking it for me suddenly realised that unlike me he wasn't wearing anything to cloak his thermal image – I won't tell you what happened to him next, as I don't want to give you nightmares – suffice it to say that at least it kept the Predator occupied long enough for me to make my excuses and exit stage right! (© Dr Karl Shuker)

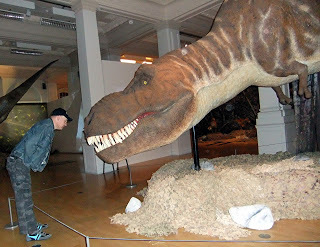

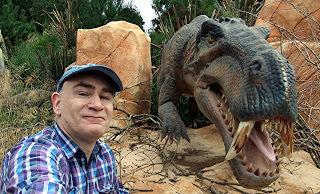

There I was, minding my own business walking round the small West Midlands, England, town of Cradley Heath, when, happening to step inside a sci-fi/comic shop, who should I encounter there but the Predator! I can only assume that my trusty leather biker jacket helped to conceal me from its thermal imaging capability long enough for me to get this photo snapped of me alongside it; if you're wondering why the photo is a little blurry, it's because the (ex) person taking it for me suddenly realised that unlike me he wasn't wearing anything to cloak his thermal image – I won't tell you what happened to him next, as I don't want to give you nightmares – suffice it to say that at least it kept the Predator occupied long enough for me to make my excuses and exit stage right! (© Dr Karl Shuker) Face to face with a life-sized Tyrannosaurus rex model at a dedicated T. rex exhibition held at Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery in the West Midlands, England, during 2010 – it's not often that you get the chance to stare down a T. rex, although in this particular instance the only thing that I seemed to be staring down was its nostrils; Jurassic Park claimed that as long as you stood perfectly still, a T. rexwould be unable to detect you, so what better time to put this claim to the test?? © Dr Karl Shuker)

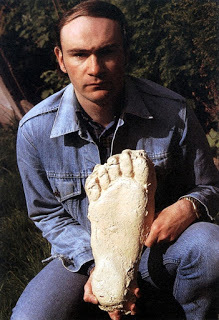

Face to face with a life-sized Tyrannosaurus rex model at a dedicated T. rex exhibition held at Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery in the West Midlands, England, during 2010 – it's not often that you get the chance to stare down a T. rex, although in this particular instance the only thing that I seemed to be staring down was its nostrils; Jurassic Park claimed that as long as you stood perfectly still, a T. rexwould be unable to detect you, so what better time to put this claim to the test?? © Dr Karl Shuker)  Holding a cast of a 16-inch-long bigfoot (sasquatch) footprint discovered at Grays Harbor, in Washington State, USA, during 1982; I purchased this particular cast from veteran bigfoot researcher Prof. Grover Krantz during the early 1990s (© Dr Karl Shuker)

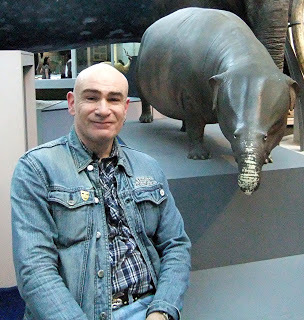

Holding a cast of a 16-inch-long bigfoot (sasquatch) footprint discovered at Grays Harbor, in Washington State, USA, during 1982; I purchased this particular cast from veteran bigfoot researcher Prof. Grover Krantz during the early 1990s (© Dr Karl Shuker) Sharing some quality time with a life-sized Moeritherium statue at London's Natural History Museum in 2014; this was a very early genus of proboscidean living during the Eocene epoch 37-35 million years ago in northern and western Africa, but dying out without giving rise to any modern-day elephant lineage; initially I was very puzzled that this statue's trunk seemed to have been rubbed so vigorously that much of its surface had lost its colour – why would this have happened? Then Facebook friend Adam Naworal reminded me that it was traditional to rub elephant statues for good luck, so that may well explain the otherwise anomalous case of the mutilated Moeritherium; fortunately, however, this doesn't seem to have traumatised him, as he seemed happy enough to be with me (© Dr Karl Shuker)

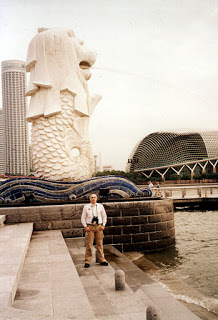

Sharing some quality time with a life-sized Moeritherium statue at London's Natural History Museum in 2014; this was a very early genus of proboscidean living during the Eocene epoch 37-35 million years ago in northern and western Africa, but dying out without giving rise to any modern-day elephant lineage; initially I was very puzzled that this statue's trunk seemed to have been rubbed so vigorously that much of its surface had lost its colour – why would this have happened? Then Facebook friend Adam Naworal reminded me that it was traditional to rub elephant statues for good luck, so that may well explain the otherwise anomalous case of the mutilated Moeritherium; fortunately, however, this doesn't seem to have traumatised him, as he seemed happy enough to be with me (© Dr Karl Shuker) Alongside Singapore's iconic merlion fountain-statue in 2005; the merlion is a legendary lion-headed fish known worldwide as a symbol of Singapore, and it is epitomised by this magnificent 28-ft-tall statue created by sculptor Lim Nang Seng during 1971-1972, and relocated in 2002 to a promontory in Singapore's Merlion Park(© Dr Karl Shuker)

Alongside Singapore's iconic merlion fountain-statue in 2005; the merlion is a legendary lion-headed fish known worldwide as a symbol of Singapore, and it is epitomised by this magnificent 28-ft-tall statue created by sculptor Lim Nang Seng during 1971-1972, and relocated in 2002 to a promontory in Singapore's Merlion Park(© Dr Karl Shuker)I hope that you've enjoyed this inaugural meander through my collection of crypto-selfies. Look out for further selections in future ShukerNature posts!

Published on September 03, 2015 21:02

August 31, 2015

PRESENTING THE TSMOK STATUE AT LAKE LEPEL IN BELARUS - AN AQUATIC DRAGON, A FLIPPERED WATER-DEER, OR A LONG-NECKED SEAL?

Lepel Tsmok, the tsmok statue, immediately after its ceremonial unveiling at Lake Lepel in Belarus on 9 November 2013 (© Alexander "Tarantino" Zhdanovich /

cmok.budzma.org/node/81

on

http://labadzenka.by/?p=25052

)

Lepel Tsmok, the tsmok statue, immediately after its ceremonial unveiling at Lake Lepel in Belarus on 9 November 2013 (© Alexander "Tarantino" Zhdanovich /

cmok.budzma.org/node/81

on

http://labadzenka.by/?p=25052

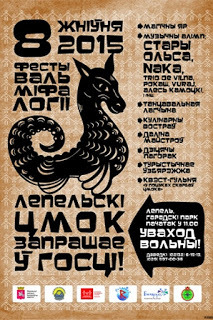

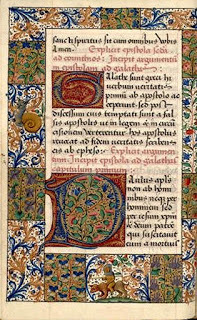

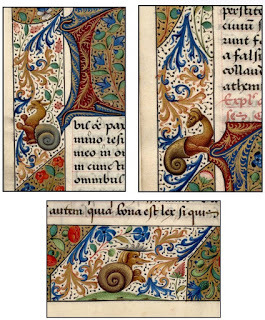

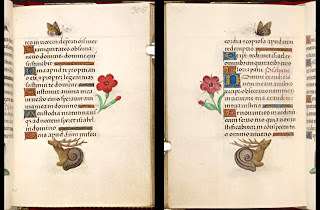

)Earlier this month, on 8 August 2015, the city of Lepel in Belarus's Vitebsk Province hosted an international festival of mythology entitled 'On a Visit to Lepel Tsmok' (click here to access its full programme of events). Among the varied array of subjects featured in this festival's talks and presentations was Lepel's very own legendary monster, one that was once virtually unknown to the outside world. Thanks to a wonderful statue here, however, all that is now changing, rapidly. But, as they say, to begin at the beginning…

Publicity poster for Lepel's international festival of mythology, depicting Lepel Tsmok (© 'On a Visit to Lepel Tsmok' international festival)

Publicity poster for Lepel's international festival of mythology, depicting Lepel Tsmok (© 'On a Visit to Lepel Tsmok' international festival)On 14 September 2013, Lepel celebrated its 574thbirthday – and as part of those celebrations, a specially-commissioned statue was officially installed on the shores of Lake Lepel, a large body of freshwater that has always been a popular sight and attraction among visitors and locals alike here, and bordered today by Tract Tsmok, the city's park. Now, however, it is even more special, thanks to this remarkable, unique statue – which, following its ceremonial unveiling on 9 November 2013, swiftly become a veritable magnet for photo opportunities, its success in attracting tourists eager to see it and be photographed alongside it exceeding even the already high expectations held by the city's ruling council when originally sanctioning its creation.

For not only is the Lake Lepel statue both spectacular and highly photogenic, but in addition its subject is certainly no ordinary one. What it portrays is a tsmok – a legendary medieval water dragon of a type scarcely known outside Belarus and Lithuania (until 1793, Lepel was part of Lithuania, lying directly to the west of Belarus), but a few of which are said still to inhabit this lake's mysterious depths, at least according to traditional Lepel lore.

Vladzimir Karatkievich's novel Hrystos Pryzyamlіўsya ¢ Garodnі: Evangelle Іudy Hell ('Christ Has Landed in Grodno: The Gospel of Judas'), published in 1990 (© Vladimir Karatkevich)

Vladzimir Karatkievich's novel Hrystos Pryzyamlіўsya ¢ Garodnі: Evangelle Іudy Hell ('Christ Has Landed in Grodno: The Gospel of Judas'), published in 1990 (© Vladimir Karatkevich)The idea for the statue, which has been formally dubbed Lepel Tsmok, came from ethnographer Vladimir Shushkevich – aka 'Valatsuga' (Valadar) – whose home city is Lepel, where he has lived for many years, and who has a longstanding interest in the mythology of its fabled water beasts. Fellow Belarusian ethnographer Nikolai Nikiforovsky has also written about tsmoks, and they were mentioned by Slavic culture researcher Alexander Afanasyev too. In particular, however, Shushkevich is well-acquainted with esteemed Belarusian author Vladzimir Karatkievich's historical novel Hrystos Pryzyamlіўsya ¢ Garodnі: Evangelle Іudy Hell ('Christ Has Landed in Grodno: The Gospel of Judas'), published in 1990, which in its first section, 'The Fall of the Fiery Serpent', draws upon Lepel folklore chronicling how 40 tsmok were allegedly killed overnight in Lake Lepel during the Middle Ages. It also describes their morphological appearance, referring to them as behemoths with the head of a deer or snake and the body of a seal.

After Shushkevich conceived and publicised at various cultural and tourist festivals his proposed project of producing this tsmok statue, it was formally approved by an international jury from the European Union, along with nine other initiatives, all of which focused upon promoting sustainable rural tourism in Russia and Belarus. However, it was Shushkevich's statue project that received the largest EU grant – 2900 euros.

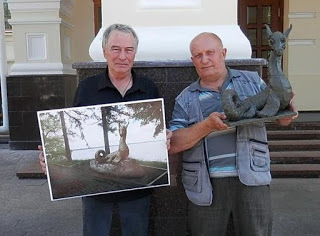

Leo Oganov and Vladimir Shushkevich, with Oganov's plasticine scale model of his tsmok statue (© Lepel.by)

Leo Oganov and Vladimir Shushkevich, with Oganov's plasticine scale model of his tsmok statue (© Lepel.by)The sculptor selected by the Arts Council in the Regional Executive Committee to produce Lepel Tsmok was Leo Oganov (sometimes spelt Aganov) from Minsk, Belarus's capital, who had already received plaudits for a sculpture honouring a Grand Duchy of Lithuania leader that he had presented to Lepel in 2010, and which stands in the city's main square. (There is also a mermaid statue in Lepel, produced by Igor Golubev a year earlier.) Oganov prepared plasticine scale models of several different reconstructions of the tsmok, one of which resembled a typical fire-breathing, winged, non-aquatic dragon, but after much debate the eventual choice was very different, much more interesting, and extremely eyecatching.

The material that Oganov's Lepel Tsmok would be made from also became an important subject for debate. It was felt that bronze would prove too expensive, but other, more viable options included cast iron or silumin (a silicon-aluminium alloy). Cast iron was the final choice, bestowing upon it a silvery sheen reminiscent of shining fish scales, an appropriate look for an aquatic creature. When the statue was complete, it weighed just over 1 ton, and was 5.5 ft tall.

Rear view of Lepel Tsmok, showing its dorsal ridge (© Alexander "Tarantino" Zhdanovich / cmok.budzma.org/node/81 on http://labadzenka.by/?p=25052)

Rear view of Lepel Tsmok, showing its dorsal ridge (© Alexander "Tarantino" Zhdanovich / cmok.budzma.org/node/81 on http://labadzenka.by/?p=25052)Oganov drew inspiration for Lepel Tsmok's morphology from traditional, folkloric descriptions of this water monster, including those contained in Karatkievich's above-cited novel, but certain potentially fragile and therefore breakable features present in his original model of it needed to be amended or omitted entirely, in order to avoid the risk of subsequent damage to the statue once installed. These included a 'moustache' of catfish-like barbels around its mouth (omitted), a crest upon its head (reduced to a bare minimum), and a mane upon its neck (omitted). It was also made more people-friendly than the original tsmok dragons of lore (as well as less expensive to produce) by excluding wings, plus any suggestion of fire-breathing, human-devouring, and general offensiveness, but adding an amiable, friendly expression to its face.

The result is one of the most distinctive cryptid/legendary monster representations that I have ever seen (albeit only online so far). Overall, Lepel Tsmok resembles a fascinating composite of aquatic dragon, female (antler-lacking) water-deer, and long-necked seal. For whereas the long curling scaly tail is definitely dragonesque, its face and large ears are decidedly cervine (or even equine if its mane had been retained), but its overall body shape and flippers instantly recall those of a seal, particularly a long-necked one (as documented in detail by me here and here on ShukerNature).

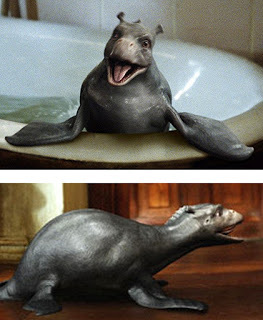

Two stills from the 2007 movie The Water Horse: Legend of the Deep, showing this cryptid in its small, juvenile stage (© Columbia Pictures)

Two stills from the 2007 movie The Water Horse: Legend of the Deep, showing this cryptid in its small, juvenile stage (© Columbia Pictures)It also reminds me a little of the juvenile stage of the eponymous cryptid in the wonderful 2007 fantasy movie The Water Horse: Legend of the Deep, which was based upon British author Dick King-Smith's children's novel The Water Horse (1990).

But just to confirm that Oganov's silvery tsmok is indeed true if not to life than at least to lore, placed alongside its statue in its installed form as an incorporated part of the complete sculpture is a representation in cast iron of an open book, upon whose pages is carved a written description of the tsmok's appearance as excerpted directly from Karatkievich's novel.

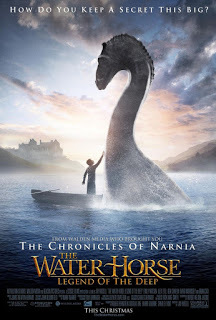

Publicity poster for the 2007 movie The Water Horse: Legend of the Deep (© Columbia Pictures)

Publicity poster for the 2007 movie The Water Horse: Legend of the Deep (© Columbia Pictures)Today, almost two years on from its ceremonial unveiling, Oganov's Lepel Tsmok is inordinately popular, a veritable Nessie of the East has been born, with souvenirs and other likenesses of it sold nearby, and photos of visitors posing alongside it contained in numerous holiday albums and shared countless times online in social networking sites.

It is especially favoured by visitors about to be wed or newly-wed, however, because according to Lepel legend yet again, if offerings of food and drink from a wedding feast are brought to a tsmok's watery abode and left there, for it to consume at its leisure, the monster will bless the marriage and bestow good fortune upon the bride and groom. Today, such tributes are not normally brought to the tsmok statue, but newly-weds nonetheless derive great joy from posing alongside it, if only on the off-chance that doing so will in itself be sufficient for the magical, elusive creature that it portrays to look upon their union benevolently and grant them future happiness together.

From an obscure provincial monster of (very) local fable and fame, the tsmok seems set to acquire international celebrity status before much longer. And when it does, remember that, at least in English, you read it here first!

Leo Oganov's Lepel Tsmok (© Alexander "Tarantino" Zhdanovich /

cmok.budzma.org/node/81

on

http://labadzenka.by/?p=25052

)

Leo Oganov's Lepel Tsmok (© Alexander "Tarantino" Zhdanovich /

cmok.budzma.org/node/81

on

http://labadzenka.by/?p=25052

)Finally: Poland's traditional folklore contains a dragon-related tale that features the similar-sounding Smok. This was the dragon of Wawel Hill in Krakow, Poland, which had terrorised the city until Skuba, a canny cobbler's apprentice, stuffed a baited lamb with sulphur. After eating it, Smok was consumed with such a fiery thirst that he drank without pause from a nearby stream until finally the sulphur reacting with the vast quantity of imbibed water caused the doomed dragon to explode.

Incidentally, in 2011 a very large species of Polish carnivorous archosaurian reptile from the late Triassic Period 205-200 million years that may constitute a species of theropod dinosaur was officially christened Smok wawelski, in honour of this Polish dragon.

A souvenir ornament of Krakow's Smok, obtained from a friend several years ago (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Until my present ShukerNature blog article, virtually no information about the Belarusian tsmok existed in English, so I have relied very extensively upon translations of various Belarusian and Russian articles as my primary sources. Of these, a detailed online news article in Cyrillic script by Tatiana Matveeva, posted on 15 June 2013, was particularly beneficial to my researches – click here to access it directly.

And to read all about plenty of other unusual and unexpected dragon varieties from around the world, be sure to check out my recent book Dragons in Zoology, Cryptozoology, and Culture .

Published on August 31, 2015 15:47

August 30, 2015

MEDUSA'S MENAGERIE - NAME-CHECKING SOME ZOOLOGICAL GORGONS FROM THE PRESENT AND THE PAST

Photo-bombed by a gorgonopsid – it could only happen to me! © Dr Karl Shuker)

Photo-bombed by a gorgonopsid – it could only happen to me! © Dr Karl Shuker)Deriving their name from 'gorgos', an ancient Greek word translating as 'dreadful', the gorgons are undoubtedly among the most infamous, terrifying monsters in classical Greek mythology. A trio of nightmarish sisters born to the ancient sea deities Phorcys and Ceto, each of these three horrific entities was feared for the writhing, seething, sibilant mass of living venomous serpents that composed her hair, and even more so for her hideous visage's dreadful gaze, which was absolutely petrifying, literally – because anyone who looked directly into her face and eyes was instantly and irrevocably turned to stone.

The decapitated head of Medusa, slain by Perseus, as painted by Peter Paul Rubens, c.1617-1618; intriguingly, note that among the snakes breaking free from her hair following her death is an amphisbaena (head at each end of its body) directly below her head, and a very strange-looking fox-headed serpent to the left of the amphisbaena (separating the two is a scorpion) - click to enlarge (public domain)

The decapitated head of Medusa, slain by Perseus, as painted by Peter Paul Rubens, c.1617-1618; intriguingly, note that among the snakes breaking free from her hair following her death is an amphisbaena (head at each end of its body) directly below her head, and a very strange-looking fox-headed serpent to the left of the amphisbaena (separating the two is a scorpion) - click to enlarge (public domain)Ironically, the two immortal gorgons, Stheno and Euryale, scarcely feature at all in Greek mythology and are therefore all but forgotten beyond the cloistered domain of classical scholars, even though one might have expected that their invulnerable, inviolate nature coupled with their lethal power of petrification would surely have set them in good stead indeed as truly daunting opponents for any of the famous Greek heroes to vanquish. However, it is commonly believed that their existence was a later addition to an original myth of just a single, mortal gorgon, because there are so many trinities of female monsters or other entities in Greek mythology (e.g. the Graeae or Grey Sisters, the Furies or Erinyes, the Horae, the Charites or Graces), so this may well explain, their virtual absence from classical legend.

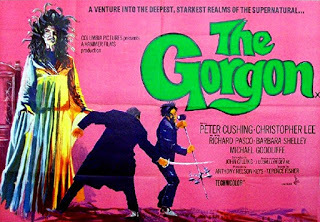

(Interestingly, the premise of a 1964 British horror movie made by Hammer Films, starring Christopher Lee and Peter Cushing, and entitled The Gorgon was the survival into modern times of one of the two immortal gorgons; but the film's researchers apparently made a major error, because they named her as Megaera, who in Greek mythology wasn't a gorgon at all, but was instead one of the three Furies, together with Tisiphone – erroneously named in this same movie as the second immortal gorgon – and Alecto.)

Poster advertising the 1964 Hammer Films horror movie The Gorgon (© Columbia Pictures/reproduced here on the basis of non-commercial fair use only)

Poster advertising the 1964 Hammer Films horror movie The Gorgon (© Columbia Pictures/reproduced here on the basis of non-commercial fair use only)Conversely, it is the third gorgon, that single mortal representative, who has seized virtually all of the public attention afforded to this terrifying trio. Her name? Medusa.

Medusa's horror-laden history has assumed many forms during the countless tellings and retellings by all manner of writers, chroniclers, and narrators down through the ages – even including variants in which she was originally a stunningly beautiful maiden but was transformed into a merciless, embittered monster with deadly gaze after finding disfavour with one or other of the Greek deities. Irrespective of her origin, however, Medusa was eventually slain by the demigod hero Perseus, who skilfully succeeded in slicing off her head with his sword while only looking at her indirectly, via a reflection in the highly-polished surface of his mirrored shield – a gift to him from his divine protector, the goddess Athena.

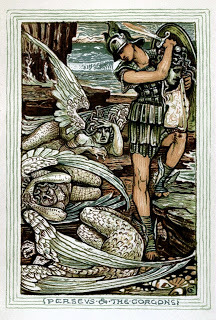

Perseus and the gorgons, with Perseus holding up the decapitated head of Medusa; illustrated by Walter Crane for Nathaniel Hawthorne's A Wonder-Book For Girls and Boys, 1893 edition (public domain)

Perseus and the gorgons, with Perseus holding up the decapitated head of Medusa; illustrated by Walter Crane for Nathaniel Hawthorne's A Wonder-Book For Girls and Boys, 1893 edition (public domain) Perseus was the very first of the classical Greek heroes, who went on to become the legendary founder of Mycenae. His father was the god Zeus, his mother Danaë, a daughter of King Acrisius of Argos and his wife Queen Eurydice, whom Zeus famously visited and impregnated in the guise of a shower of golden rain.

In later ages, carvings of Medusa's head were incorporated in a number of classical architectural features, such as columns, arches, door panels, decorative grilles, sarcophagi, fountains, statues, and mosaics, to ward off evil spirits, and the image was also a popular depiction on protective amulets. This visual device is known as a gorgoneion.

A gorgoneion entitled 'Medusa and the Seasons', in a Roman mosaic found at Palencia, Spain, and dated at 167-200 AD (© Luis Garcia/Wikipedia)

A gorgoneion entitled 'Medusa and the Seasons', in a Roman mosaic found at Palencia, Spain, and dated at 167-200 AD (© Luis Garcia/Wikipedia)Today, Stheno and Euryale remain largely unknown; but despite having been slain, Medusa still lives on, or at least her name and that of her monstrous kind do – which is due not only to the popularity of her memorable legend but also, in turn, because both 'gorgon' and 'Medusa' have been applied to a wide range of very remarkable, entirely real creatures, some living, others once-living. So permit me now to take you all on a brief, ShukerNature-led visit to the extraordinary menagerie of Medusa.

HOW AN AQUATIC GORGON-HEAD BECAME AN INTERNET ALIEN – OR WAS IT THE OTHER WAY ROUND?!

According to a report posted online during late September 2014 by Britain's Sunday Express newspaper and written by Levi Winchester, a 54-year-old Singapore fisherman named Ong Han Boon had recently captured in waters off the southern Singapore island of Sentosa a creature so bizarre in appearance that he seriously wondered whether it might be an alien, an extraterrestrial! Before releasing it back into the sea, he filmed a short video of it that duly appeared in the above-noted newspaper report (click here to view it there), and on 28 September a Singapore-based member of Facebook called Jr Saim publicly shared the video on his FB timeline (click here to view it on Facebook). The video swiftly went viral, soon appearing – and still appearing – on numerous news and video-sharing websites.

Still from the Singapore Gorgonocephalus video (© Ong Han Boon)

Still from the Singapore Gorgonocephalus video (© Ong Han Boon) But what was the creature that it showed? Those of an ophidiophobic disposition who have not already watched it might choose to avert their eyes from the video, because the entity in it looks disturbingly like a hideous matted wig composed of writhing, twisting, curling and uncurling serpentine tresses – a veritable Medusa scalp, in fact. And nomenclaturally, if not taxonomically, that is precisely what it is, because its scientific binomial name is Gorgonocephalus caputmedusae – 'gorgon-headed Medusa head'.

Happily, however, this grotesque entity lacks the petrifying power of its namesake, and it isn't of extraterrestrial origin either, because in reality it is nothing more startling than a sea-dwelling starfish, or, more specifically, a basket star. These particular invertebrates belong to a taxonomic class of echinoderms known as ophiuroids, whose most famous members are the notably long-limbed brittle stars.

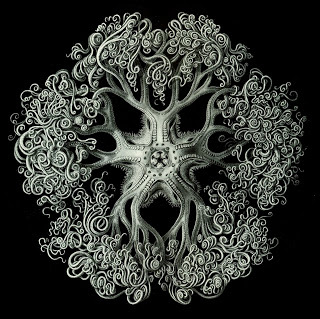

Gorgonocephalus arborescens

, from Alfred Edmund Brehm's famous multi-volume animal encyclopaedia Tierleben ('Animal Life'), which was originally published in 6 volumes during the 1860s and then republished as an expanded 10-volume second edition during the 1870s (public domain)

Gorgonocephalus arborescens

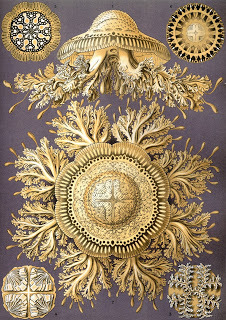

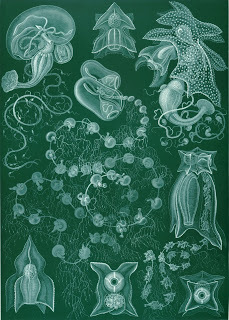

, from Alfred Edmund Brehm's famous multi-volume animal encyclopaedia Tierleben ('Animal Life'), which was originally published in 6 volumes during the 1860s and then republished as an expanded 10-volume second edition during the 1870s (public domain)In a Gorgonocephalus basket star, however, of which there are several species, each of the five arms radiating from its central disc repeatedly divides and subdivides, yielding the somewhat disturbing, wriggling mass of miniature snake-like 'armlets' so vividly captured in the above video, and whose serpentine resemblance is heightened by their fleshy covering of pink rubbery skin. For a much more appealing, stationary representation of a Gorgonocephalus basket star, here is German biologist and artist Prof. Ernst Haeckel's exquisite rendition:

Gorgonocephalus

basket star, appearing in Prof. Ernst Haeckel's gorgeously-illustrated, 2-volume tome Kunstformen der Natur ('Art Forms in Nature'), published in 1904 (public domain)

Gorgonocephalus

basket star, appearing in Prof. Ernst Haeckel's gorgeously-illustrated, 2-volume tome Kunstformen der Natur ('Art Forms in Nature'), published in 1904 (public domain)And here's an illustration of a reddish-coloured species named after the famous 19th-Century American zoologist and geologist Prof. Louis Agassiz – Gorgonocephalus agassizi:

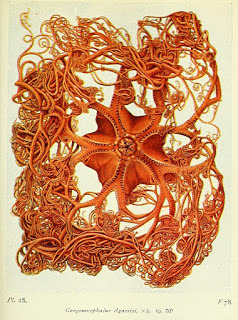

Gorgonocephalus agassizi

, 1800s rendition (public domain)

Gorgonocephalus agassizi

, 1800s rendition (public domain)When seeking prey, Gorgoncephalus takes up a stationary position and then spreads out its innumerable tiny armlets like a basket. Each of these small but highly dexterous armlets is equipped with hooks and spines to seize and hold prey, normally krill or other planktonic forms, which they then convey to the mouth on the underside of the animal's central disc with the added assistance of a series of suctioned tube-feet.

A GORGON-GUTTED RIBBON WORM

No less grotesque and slightly stomach-churning than the Gorgonocephalus video of 2014 was a more recent one, seemingly first aired in May 2015 but again swiftly going viral and appearing on numerous websites, but featuring, as it turned out, another gorgon-dubbed creature with equally discomforting behaviour. The video (whose original ownership is presently unknown to me) can be viewed here , and shows a long blood-red worm-like creature originating in the seas off Thailand but resting on someone's hand that suddenly releases from its mouth a long thick white tube from which an intricate mass of white filaments shoot forth and which momentarily writhe about before sticking to the person's hand – almost as if this mini-monster has disgorged a gorgon's head of serpentine hair! Nor is that my own peculiar impression – the same notion clearly occurred to others too, because the generic name of the vermiform creature in question is none other than Gorgonorhynchus. This roughly translates as 'gorgon-beaked', though the beak in this instance is actually a proboscis.

Still from the video of the Thai Gorgonorhynchus nemertean everting its proboscis on a person's hand (copyright owner currently unknown to me)

Still from the video of the Thai Gorgonorhynchus nemertean everting its proboscis on a person's hand (copyright owner currently unknown to me) As someone who studied such creatures during a university project, I was very familiar with this animal's behaviour, repulsive though it evidently seemed to many other viewers of the video, judging from various comments posted concerning it. The creature is a nemertean, or ribbon worm, Nemertea (aka Rhynchocoela) being a phylum of invertebrates whose members are characterised by their often very long slender bodies and in particular by their possession of a lengthy prey-capturing proboscis. This distinctive organ is normally held inside the worm's mouth within its own sheath (the rhynchocoel) and in an inverted, inside-out conformation, but when the worm encounters a potential prey victim, it is instantly and quite explosively shot out through the worm's mouth in everted form. The proboscis usually bears hooks at its tip that seize the prey, and sometimes inject it with venom too, after which the prey is swiftly hauled back inside the worm's body via the proboscis's immediate muscle-powered retraction through the mouth in inverted form once more.

Illustration of Gorgonorhynchus reptens everting its branched proboscis after feeling threatened from being touched (© Rachel Koning/Wikipedia)

Illustration of Gorgonorhynchus reptens everting its branched proboscis after feeling threatened from being touched (© Rachel Koning/Wikipedia)In most nemerteans, the proboscis is a long, simple tube, but in certain species, including those of the genus Gorgonorhynchus, the tube possesses many branching sticky filaments that divide and subdivide in a manner analogous to the armlets of the basket star Gorgonocephalus, and which, again like the latter's armlets, wriggle and writhe as if they were a multitude of tiny snakes, before wrapping themselves around the prey, encapsulating it in an adhesive mass from which it cannot pull out, almost like the gossamer produced by a spider. In effect, therefore, when the nemertean everted its proboscis all over the person's hand, it was either stressed or feeling threatened from being handled or it was reacting as if the hand were prey, and hence was vainly attempting to wrap it up in its proboscis's sticky filaments.

GORGONS FROM PREHISTORY

Moving now from the present back to the (very) far-distant past: in the mid to late Permian Period (265 to 252 million years ago), when dinosaurs were still merely a future twinkle in the eye of evolution, a reptile-originating lineage existed whose members were so genuinely monstrous in form and size that in 1876 the great 19th-Century palaeontologist Prof. Sir Richard Owen fittingly named them after Greek mythology's own historical (albeit not prehistorical!) horrors, the gorgons. For he christened their type genus and species Gorgonops torvus, after which genus their entire taxonomic group (currently deemed a suborder) duly derived its name – Gorgonopsia – in 1895, as dubbed by British palaeontologist Prof. Harry G. Seeley.

Also called gorgonopsians, the gorgonopsids belong to the taxonomic order of synapsid reptiles known as Therapsida, whose members are often referred to colloquially as the mammal reptiles or mammal-like reptiles, and do indeed belong to the same taxonomic clade, Theriodontia, as do true mammals.

A life-sized animatronic gorgonopsid on exhibition at the West Midlands Safari Park in England, August 2015 (© Dr Karl Shuker)

A life-sized animatronic gorgonopsid on exhibition at the West Midlands Safari Park in England, August 2015 (© Dr Karl Shuker)Gorgonopsids were among the largest of all carnivorous vertebrates alive at that time (the biggest, Inostrancevia from northern Russia, was up to 11.5 ft long, the size of a large bear or small rhinoceros, with the aptly-named Titanogorgan maximus from Tanzania only slightly smaller), and they were certainly the dominant ones. Even so, in genera such as Gorgonops itself, native to what is now Africa, their most memorable features were their enormous sabre-like canine teeth – so large that they almost projected below their lower jaw.

Gorgonopsids also had pillar-like legs that arose from underneath their bodies like those of mammals rather than splaying from their sides like reptiles. This important anatomical feature enabled them to move more swiftly and energy-efficiently than their lumbering herbivorous prey, which included some very large, hefty plant-eating reptiles known as pareiasaurs, some of which, like Scutosaurus, were armoured for protection.

The gorgonopsid Inostrancevia alexandri attacking the pareiasaur Scutosaurus karpinski (© Dmitry Bogdanov/Wikipedia)

The gorgonopsid Inostrancevia alexandri attacking the pareiasaur Scutosaurus karpinski (© Dmitry Bogdanov/Wikipedia)The gorgonopsids perished entirely during the mass extinction at the end of the Permian, the only theriodont lineage to become extinct during that catastrophic event, but they were sensationally resurrected in CGI if not in life itself during the early 2000s by Britain's highly popular ITV sci-fi television show Primeval. In the very first episode, originally screened in Britain on 10 February 2007, a marauding gorgonopsid of the genus Gorgonopsequipped with a monstrously large pair of upper canines confidently stepped forth from out of the Permian and into the present day via a temporary gateway through time known as an anomaly, wreaking havoc in Gloucestershire's Forest of Dean, tenaciously stalking the perplexed scientists sent to deal with this ferocious anachronistic therapsid, and vibrantly demonstrating to enthralled viewers everywhere that carnivorous dinosaurs were not the only prehistoric predators that oozed charisma and exuded terror in equal proportions. Moreover, another Gorgonopsfeatured in the final episode of this first series of Primeval.

A gorgonopsid on the prowl in Episode 1, Series 1 of Primeval (© ITV Studios/ProSieben/Impossible Pictures/Treasure Entertainment/M6 Films)

A gorgonopsid on the prowl in Episode 1, Series 1 of Primeval (© ITV Studios/ProSieben/Impossible Pictures/Treasure Entertainment/M6 Films) Nevertheless, bearing in mind that prior to Primevalcoming along, gorgonopsids were scarcely known beyond the palaeontological community, to utilise one as the star monster in the opening episode of a brand-new, potentially major new sci-fi show rather than going for the safer tried-and-trusted option of a rampaging dinosaur was not only inspired but also very brave – and yet, as it turned out, highly successful too. All of which only goes to show that, clearly, you can't keep a good gorgon, or gorgonopsid, down!

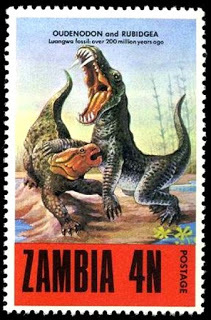

Two African therapsids - the gorgonopsid Rubidgea battling a dicynodont Oudenodon, as depicted on a postage stamp issued in 1973 by Zambia, from my personal collection (© Zambia postal service)

Two African therapsids - the gorgonopsid Rubidgea battling a dicynodont Oudenodon, as depicted on a postage stamp issued in 1973 by Zambia, from my personal collection (© Zambia postal service)THE FRAGILE, STINGING SEA-FLOWERS OF MEDUSA

Needless to say, no documentation of real-life gorgon namesakes could be complete without considering the most famous example of all, named specifically after the most famous gorgon of all – Medusa herself.

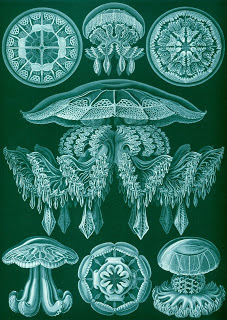

In the phylum Cnidaria, there are two basic body forms, both of which are produced by many species, but only one or the other by some. The two body forms are the sessile, stalk-bodied, tentacle-headed, hydra-like polyp; and the free-swimming, umbrella-shaped, often (but not always) tentacle-fringed, jellyfish-like medusa. The principal taxonomic classes of cnidarian are Hydrozoa (the hydrozoans, including the hydras, freshwater jellyfishes, and siphonophores), Staurozoa (the stalked jellyfishes), Scyphozoa (the true jellyfishes), Cubomedusae (the box jellyfishes), and Anthozoa (the sea anemones and corals). Certain hydrozoans, scyphozoans, and cubomedusans all produce a medusa form, many of which are usually equipped with long stinging tentacles that fancifully resemble the living snakelock hair fringing the dread face of Medusa, thereby earning the cnidarian medusa form its name, as coined for it in 1752 by none other than Linnaeus himself.

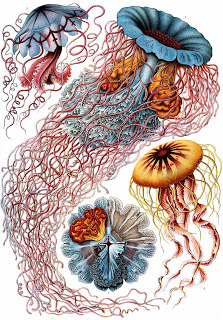

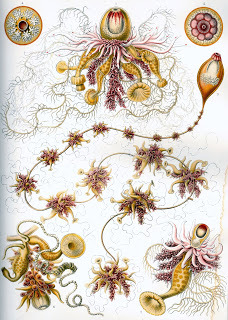

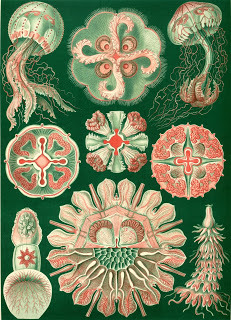

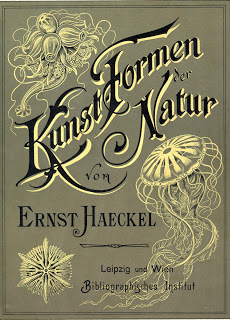

And so, what better way to bring to a memorable close our visit to Medusa's menagerie than to savour some of the most extravagantly exquisite illustrations ever produced of the varied types of cnidarian medusae, often resembling bizarre, exotic sea-flowers, as contained within Hackel's artistic masterpiece Kunstformen der Natur ('Art Forms in Nature'), published in 1904. Please click the images to enlarge them.

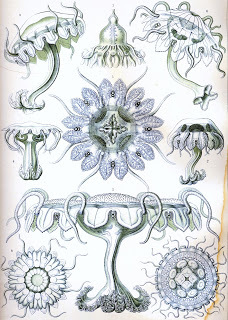

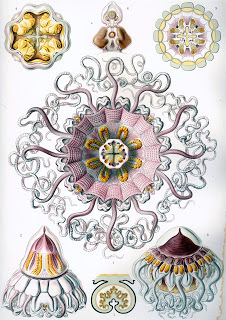

Three species of Discomedusae, true jellyfishes belonging to the class Scythozoa (public domain)

Three species of Discomedusae, true jellyfishes belonging to the class Scythozoa (public domain) More Discomedusae (public domain)

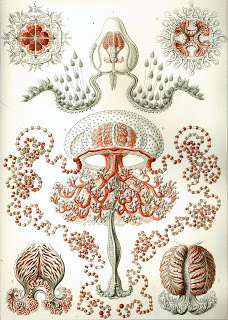

More Discomedusae (public domain) Various species of Narcomedusae, a hydrozoan order whose species normally lack a polyp stage (public domain)

Various species of Narcomedusae, a hydrozoan order whose species normally lack a polyp stage (public domain) Various species of Trachymedusae, another hydrozoan order whose species never produce a polyp stage, only reproducing sexually via medusae (public domain)

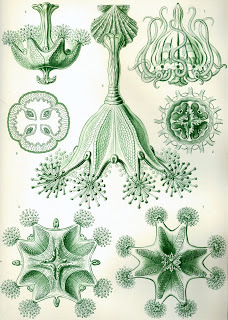

Various species of Trachymedusae, another hydrozoan order whose species never produce a polyp stage, only reproducing sexually via medusae (public domain) Various species of Leptomedusae or thecate hydroids, a hydrozoan order whose species produce ensheathed polyp colonies (the protective sheath is known as a theca or perisarc), as well as sexually-reproducing medusae (public domain)

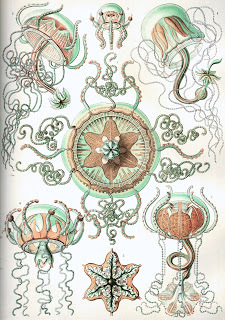

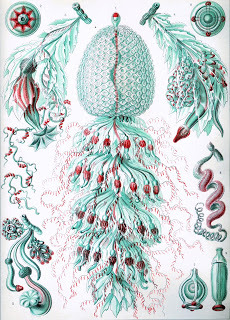

Various species of Leptomedusae or thecate hydroids, a hydrozoan order whose species produce ensheathed polyp colonies (the protective sheath is known as a theca or perisarc), as well as sexually-reproducing medusae (public domain) Views of the siphonophore Physophora hydrostatica – like all siphonophores, what looks like a single large complex organism equipped with bell, tentacles, etc, is in reality a super-organism, consisting of an entire colony of highly-specialised individual organisms, each of which is one of the super-organism's organs, e.g. one organism is the bell, another organism is one of the tentacles, yet another is another of the tentacles, etc (public domain)

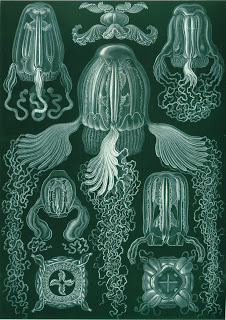

Views of the siphonophore Physophora hydrostatica – like all siphonophores, what looks like a single large complex organism equipped with bell, tentacles, etc, is in reality a super-organism, consisting of an entire colony of highly-specialised individual organisms, each of which is one of the super-organism's organs, e.g. one organism is the bell, another organism is one of the tentacles, yet another is another of the tentacles, etc (public domain) More siphonophores (public domain)

More siphonophores (public domain)  Views of the helmet jellyfish Periphylla periphylla, a deepsea species of true jellyfish or scyphozoan (public domain)

Views of the helmet jellyfish Periphylla periphylla, a deepsea species of true jellyfish or scyphozoan (public domain) Various species of Anthomedusae, the athecate hydroids, a hydrozoan order whose species produce polyp colonies not ensheathed in a protective sheath (the theca or perisarc), as well as sexually-reproducing medusae (public domain)

Various species of Anthomedusae, the athecate hydroids, a hydrozoan order whose species produce polyp colonies not ensheathed in a protective sheath (the theca or perisarc), as well as sexually-reproducing medusae (public domain) Various species of Stauromedusae, the stalked jellyfishes, sole members of the taxonomic class Staurozoa, whose medusae are attached rather than free-swimming (public domain)

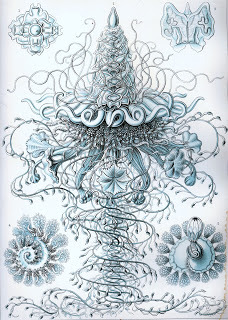

Various species of Stauromedusae, the stalked jellyfishes, sole members of the taxonomic class Staurozoa, whose medusae are attached rather than free-swimming (public domain) Various species of Cubomedusae, the box jellyfishes, which include Flecker's sea wasp Chironex fleckeri, the world's most venomous jellyfish, yet still-undiscovered by science in Haeckel's time, and remaining so until the mid-1950s (public domain)

Various species of Cubomedusae, the box jellyfishes, which include Flecker's sea wasp Chironex fleckeri, the world's most venomous jellyfish, yet still-undiscovered by science in Haeckel's time, and remaining so until the mid-1950s (public domain) More Discomedusae, true jellyfishes belonging to the class Scyphozoa (public domain)

More Discomedusae, true jellyfishes belonging to the class Scyphozoa (public domain)  Various species of rhizostome Discomedusae, true jellyfishes belonging to Scyphozoa (public domain)

Various species of rhizostome Discomedusae, true jellyfishes belonging to Scyphozoa (public domain) More siphonophores (public domain)

More siphonophores (public domain)  More species of Discomedusae, including the medusa of the familiar moon jellyfish Aurelia aurita (top centre) (public domain)

More species of Discomedusae, including the medusa of the familiar moon jellyfish Aurelia aurita (top centre) (public domain) Still more siphonophores (public domain)

Still more siphonophores (public domain)Also commemorating Medusa, incidentally, are Medusaceratops lokii (also commemorating Loki, the Norse god of evil), a late Cretaceous species of ceratopsian horned dinosaur, which inhabited what is now Montana, USA, and was formally named in 2010; and Medusagyne oppositifolia, the critically-endangered Seychelles jellyfish tree, earning its genus name from the fancied resemblance of its flower's gynoecium to Medusa's head, plus its common name from the distinctive jellyfish-like shape of its dehisced fruit, and believed extinct until some individuals were discovered on the island of Mahé during the 1970s.

The front cover of Prof. Ernst Haeckel's truly beautiful book, Kunstformen der Natur (1904) (public domain)

The front cover of Prof. Ernst Haeckel's truly beautiful book, Kunstformen der Natur (1904) (public domain)And speaking of jellyfishes: how ironic it is that in certain instances, creatures as beautiful as cnidarian medusae are also potentially lethal, due to the potency of the venom produced by their tentacles' nematocysts or stinging cells. Then again, how can we really expect anything else from organisms that are, after all, specifically named after a legendary figure feared not only for her thanatic eyes but also for the deadly nature of her living tresses?

Me and my mate the gorgonopsid (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Me and my mate the gorgonopsid (© Dr Karl Shuker)UPDATE - 31 August 2015

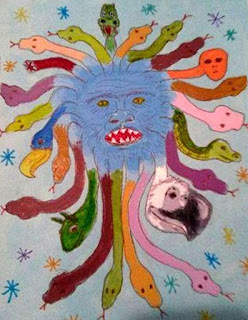

Today, I received a scan of this very different, highly original, and totally delightful Medusa illustration, drawn by crypto-enthusiast and friend Jane Cooper. Hidden amongst Medusa's traditional serpentine hair strands are several that are inspired by all manner of other creatures, including some notable cryptozoological ones, such as Nessie, the Mongolian death worm, and the Dover demon, as well as a very imposing terror bird. How many can you spot and identify? Thanks Jane!!

Medusa goes crypto!! - click to enlarge (© Jane Cooper)

Medusa goes crypto!! - click to enlarge (© Jane Cooper)

Published on August 30, 2015 15:55

August 29, 2015

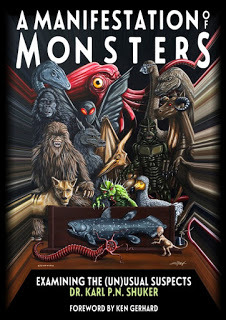

MY LATEST BOOK, A MANIFESTATION OF MONSTERS, IS NOW AVAILABLE TO PRE-ORDER ON AMAZON!

Front cover of my latest book, A Manifestation of Monsters (© Dr Karl Shuker/Michael J. Smith/Anomalist Books)

Front cover of my latest book, A Manifestation of Monsters (© Dr Karl Shuker/Michael J. Smith/Anomalist Books)I'm delighted to announce that my latest book, A Manifestation of Monsters: Examining the (Un)Usual Subjects , published by Anomalist Books and containing a foreword by my good friend and fellow cryptozoologist Ken Gerhard, is now available to pre-order on Amazon.

Please click its title above to access its own dedicated web-page on my website, which includes direct clickable links to its ordering pages on Amazon's American and British sites.

Fellow cryptozoologist and good friend Ken Gerhard, who very kindly wrote the foreword to my new book - thanks, Ken!! (© Ken Gerhard)

Fellow cryptozoologist and good friend Ken Gerhard, who very kindly wrote the foreword to my new book - thanks, Ken!! (© Ken Gerhard) And here's a summary of what inspired this 22nd book of mine and what it contains:

During the 30 years in which I have been investigating and documenting mystery creatures, my writings have been guided by countless different inspirations, but what inspired this present book was a spectacular work of art. Namely, the wonderful illustration that now graces its front cover, which was prepared by Michael J. Smith, an immensely talented artist from the USA, and which I first saw in 2012. It depicts no less than 17 cryptids and other controversial creatures, including the Loch Ness monster, bigfoot, coelacanth, mokele-mbembe, Jersey devil, chupacabra, Mongolian death worm, Tasmanian wolf, dogman, giant squid, skunk ape, and dodo.

Ever since seeing it, my notion of preparing a book inspired directly by this painting and the eclectic company of entities that it portrays has always stayed with me, but the fundamental problem that I faced if I were to do so was how to categorise them collectively.

What single term could be used that would effectively embrace, encompass, and enumerate this exceptionally diverse array of forms, as well as the range of additional creatures that would also be included in the book? 'Cryptid' was not sufficiently comprehensive, nor was 'mystery creature' or 'unknown animal', because some of the depicted beasts seem to exist far beyond the perimeters - and parameters - of what is traditionally deemed to be the confines of cryptozoology. Consequently, I eventually concluded that there was only one such term that could satisfy all of those requirements – indeed, it was tailor-made for such a purpose. The term? What else could it be? 'Monster'!

Derived from the Latin noun 'monstrum' and the Old French 'monstre', 'monster' has many different modern-day definitions - a very strange, frightening, possibly evil (and/or ugly) mythical creature; something huge and/or threatening; a malformed, mutant, or abnormal animal specimen; and even something extraordinary, astonishing, incredible, unnatural, inexplicable. These definitions collectively cover all of this book's subjects – and so too, therefore, does the single word 'monster' from which the definitions derive.

Thus it was that this became a book of monsters, but not just a book – a veritable manifestation of monsters. That is, a unique exhibition, a singular gathering, an exceptional congregation of some of the strangest, most mystifying, and sometimes truly terrifying creatures ever reported - still-unidentified, still-uncaptured, still-contentious. Even 'mainstream' species like the dodo and coelacanth, whose reality and zoological identity are fully confirmed, still succeed in eliciting controversies, and are veritable monsters - the dodo having been referred to by various researchers as a monstrous dove, and the coelacanth as a resurrected prehistoric monster.

So, if you're looking for monsters, you've certainly come to the right place, and will certainly be purchasing the right book. Just pray that once you open it and encounter the incredible creatures lurking inside, you don't live to regret your bravery – or foolishness - in having done so. In fact, just pray that you do live...

Hoping that you enjoy encountering my manifestation of monsters!!

Michael J. Smith's spectacular original artwork, 'Cryptids', which inspired my book and which now appears on its front cover – thanks, Michael!! (© Michael J. Smith)

Michael J. Smith's spectacular original artwork, 'Cryptids', which inspired my book and which now appears on its front cover – thanks, Michael!! (© Michael J. Smith)

Published on August 29, 2015 17:10

August 28, 2015

ANTLERED ELEPHANTS - OR UNLIKELY UINTATHERES?

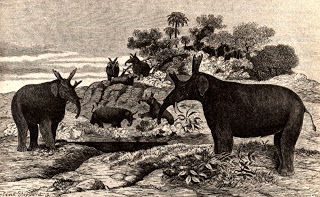

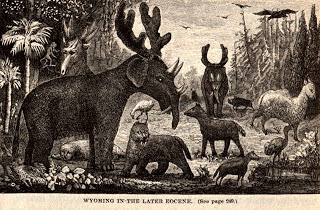

'Antlered elephants' and other North American prehistoric fauna from the Eocene epoch in what is today Wyoming, USA, as depicted in William D. Gunning's book Life History of Our Planet (1881) (public domain)

'Antlered elephants' and other North American prehistoric fauna from the Eocene epoch in what is today Wyoming, USA, as depicted in William D. Gunning's book Life History of Our Planet (1881) (public domain)Have there ever been antlered elephants? Not as far as we know – so how can the extraordinary illustration presented above be explained? The answer dates back to the intense rivalry between two eminent American fossil collectors, resulting in the so-called Bone Wars that galvanised 19th-Century palaeontology, and focuses upon the subject of one of their most fervent bouts of competitive taxonomic classification – a long-extinct but spectacularly strange-looking group of huge ungulate mammals known as uintatheres.

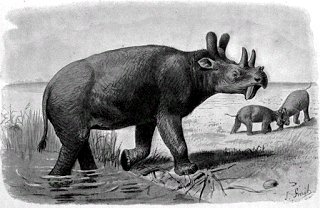

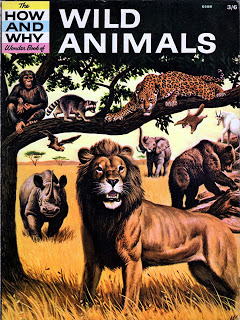

Uintatheres have always held a special place in my childhood memories because the very first artistic reconstruction of a fossil mammal's likely appearance in life that I ever saw was of a Uintatherium– vibrantly depicted on one of the opening pages of my How and Why Wonder Book of Wild Animals (1962) that my mother bought for me when I was about 4 years old during the early 1960s. I read that poor, long-suffering book so many times and with such youthful enthusiasm that it eventually fell apart, but a replacement copy was soon purchased, which I still own today, so here is that wonderful, fondly-remembered illustration:

Uintatherium

depicted by Walter Ferguson in The How and Why Wonder Book of Wild Animals (© Walter Ferguson/Transworld Publishers)

Uintatherium

depicted by Walter Ferguson in The How and Why Wonder Book of Wild Animals (© Walter Ferguson/Transworld Publishers)But what are – or were – uintatheres? Named after the mountainous Uinta region of Wyoming and Utah where their first scientifically-recorded fossils were uncovered, they belonged to the taxonomic order Dinocerata ('terrible horns'). This was an early group of extremely large, superficially rhinoceros-like ungulates (but possessing claws rather than hooves), which existed from the late Palaeocene to the mid-Eocene, approximately 45 million years ago. The males of its most famous, culminating members, the uintatheres (which existed during the mid-Eocene), bore no less than three separate pairs of blunt ossicone-like horns on their heads. These consisted of a rear pair arising from the parietal bones near the back of the skull, a middle pair arising from the maxillae or upper jaw bones, and a front pair arising from the nasal bones. Their function remains uncertain, but they may have been used for defence and/or for sexual display purposes. Also, their skull was very concave and flat in shape, and with very thick walls, thus yielding so restricted a cranial cavity that the brain was surprisingly small for such sizeable animals.

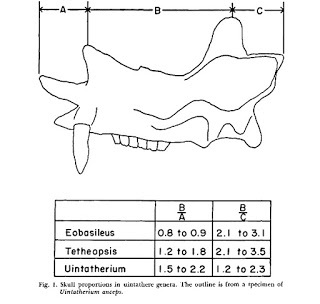

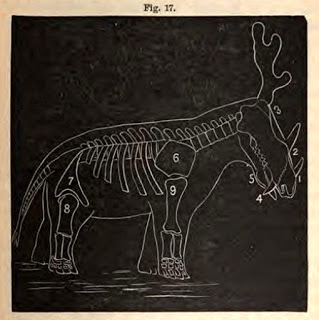

Today, two major genera of uintatheres are recognised – Uintatherium and Eobasileus (plus a few less well known ones, such as Tetheopsis) – which are very similar to one another morphologically, and are distinguished predominantly by way of certain differences in skull proportions, as delineated in the following diagram and table. These originate from the definitive work on uintathere taxonomy, North Carolina University palaeontologist Dr Walter H. Wheeler's comprehensive paper 'Revision of the Uintatheres', published in 1961 as Bulletin #14 of the Peabody Museum of Natural History, Yale University.

Skull proportions in uintathere genera (from Wheeler, 1961)

Skull proportions in uintathere genera (from Wheeler, 1961)Also, whereas the skull of Uintatherium was relatively broad, with the parietal bones positioned some way in front of the occiput (the skull's rearmost portion), in Eobasileus the skull was long and narrow, with the parietal horns further back and therefore much closer to the occiput.

In addition to their horns, male uintatheres also possessed a very sizeable pair of downward-curving upper tusks (they were much smaller in females), protected like scimitars by bony scabbard-resembling lower jaw down-growths. Behind each of these two tusks was a noticeable gap (diastema), separating the tusk on each side of the upper jaw from that side's first premolars. In Uintatherium, the maxillary horns were positioned directly above the diastema in each side of the upper jaw, whereas in Eobasileusthey were positioned further back, above the premolars.

Comparing the structure of a Uintatherium anceps skull at the Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle in Paris, France (above) with that of an Eobasileus cornutus skull at the Chicago Field Museum (below) (public domain / © Dallas Krentzel/Wikipedia)

Comparing the structure of a Uintatherium anceps skull at the Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle in Paris, France (above) with that of an Eobasileus cornutus skull at the Chicago Field Museum (below) (public domain / © Dallas Krentzel/Wikipedia)Uintatherium was a massive browsing ungulate, up to around 13 ft long, 5.5 ft tall, and up to 2 tons in weight. Only two species of Uintatherium are recognised today – North America's U. anceps (the most famous dinoceratan of all, formally named and described in 1872 by American palaeontologist Prof. Joseph Leidy), and China's more recently-recognised U. insperatus (named and described in 1981).

Only one Eobasileus species is nowadays recognised – E. cornutus, named by fellow American palaeontologist Prof. Edward Drinker Cope in 1872. This was the largest uintathere of all, and in fact the largest land mammal of any kind during its time on Earth, with a total length of around 13 ft, standing 6.75 ft high at the shoulder, and weighing up to 4.5 tons.

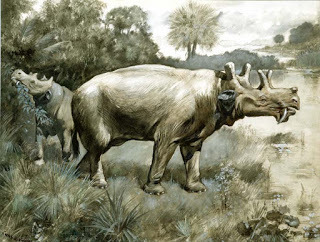

Eobasileus

as depicted masterfully and majestically by Charles Knight (public domain)

Eobasileus

as depicted masterfully and majestically by Charles Knight (public domain)Just over a century ago, however, a bewildering plethora of uintathere genera and species had been distinguished and named, due not so much to any taxonomic merit, however, but rather to the driven desire by two implacable fossil-collecting foes during the 1870s and 1880s to outdo one another in their febrile quest for palaeontological immortality and to destroy each other's scientific reputation, until their obsession eventually ruined both of them, socially and financially.

Their names? Othniel Charles Marsh (1831-1899), and Edward Drinker Cope (1840-1897).

Othniel Charles Marsh (left) and Edward Drinker Cope (right) (public domain)

Othniel Charles Marsh (left) and Edward Drinker Cope (right) (public domain)After having been professor of vertebrate palaeontology at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut, Marsh became the first curator at the Peabody Museum of Natural History at Yale University (the museum having been founded by his wealthy uncle, the philanthropist George Peabody). Conversely, Cope preferred field work to academic research, as a result of which he never held a major scientific post of any lengthy tenure, though he did become professor of zoology for a time at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, his home city.

Although they are most famous for their frenzied attempts to best one another in the description of new dinosaur species, Marsh and Cope also constantly challenged each another along similar lines in relation to their descriptions of new uintatheres. The regrettable, chaotic result was the creation not only of numerous new species but also of many new genera, several of which were named within the space of a single year, and all of which were unjustified, having been founded upon the most trivial, taxonomically insignificant of differences.

This sorry, farcical state of affairs is preserved today in the startling array of junior synonyms attached to the genus Uintatherium, including the nowadays long-nullified genera Dinoceras (coined by Marsh in 1872), Ditetrodon (Cope, 1885), Elachoceras (Scott, 1886), Loxolophodon (Cope, 1872), Octotomus (Cope, 1885), Tinoceras (Marsh, 1872), and Uintamastix (Leidy, 1872). Although I normally have little interest in abandoned names, I do feel a pang of regret for the loss of one particular example here – the wonderfully-named Dinoceras mirabile (synonymised with Uintatherium anceps), which was coined in 1872 by Marsh, and translates as 'marvellous terrible-horn' – a very evocative, accurate description of how this extraordinary beast would have looked in life.

Uintatherium

as portrayed upon a postage stamp issued by Afghanistan in 1988, from my personal collection (© Afghanistan postal service)

Uintatherium

as portrayed upon a postage stamp issued by Afghanistan in 1988, from my personal collection (© Afghanistan postal service)But what has all (or any) of this to do with antlered elephants? I'm glad you asked! Because uintatheres were indeed so astounding in form, when their first fossils were discovered palaeontologists were by no means certain which creatures were their closest relatives, and how, therefore, they should be classified. Cope, who was particularly enthralled by them, was convinced that such huge ungulates must surely be related to elephants, and he even opined that they probably possessed a long nasal trunk like elephants plus a pair of very large, wide, elephantine ears, and that they should be housed with them in the taxonomic order Proboscidea, thereby conflicting yet again with Marsh's view (in 1872, Marsh had placed them within their very own order, Dinocerata). But that was not all.

Cope also speculated that their rearmost, parietal pair of horns may have been much larger than the other two pairs, possibly even branched and covered in velvet, thereby resembling the antlers of deer. And so, in various early reconstructions of their putative appearance in life, this is exactly how uintatheres were portrayed – as antlered, large-eared, trunk-wielding pachyderms, resembling the highly unlikely outcome of an equally improbable liaison between an elephant and a moose!

Eobasileus cornutus

with elephant ears and trunk , from an August 1873 Pennsylvania Monthly article by Edward Drinker Cope (public domain)

Eobasileus cornutus

with elephant ears and trunk , from an August 1873 Pennsylvania Monthly article by Edward Drinker Cope (public domain)True, there were certain less dramatic versions – one illustration (see above) that appeared in a Pennsylvania Monthlyarticle from August 1873 by Cope concerning the uintathere species now called Eobasileus cornutus portrayed it with tall unbranched parietal horns rather than with parietal antlers (although they are still slightly palmate at their distal edges), but did gift it with an elephant's ears and trunk (as instructed by Cope). However, the two most (in)famous examples of this specific genre of reconstruction were rather more extreme, and both of them appeared in William D. Gunning's book Life History of Our Planet (1881). One of these is the following diagrammatic reconstruction:

Line diagram of a Uintatherium(spelt 'Uintahtherium' here) as an antlered elephant-like beast in Gunning's book (public domain)

Line diagram of a Uintatherium(spelt 'Uintahtherium' here) as an antlered elephant-like beast in Gunning's book (public domain)Gunning's comparisons drawn between this remarkable creature and various modern-day animals were equally memorable, albeit decidedly fanciful in parts (notably its small brain allying it with the marsupials!):

"We are as astronomers taking the parallax of a distant star. The animal which roamed along the banks of that Wyoming lake is as far from us in time as the star in space. What is its parallax? what its place in the scheme of creation? The long, narrow head with skull elevated behind into a great crest, the molar teeth and arch of the cheek-bone are characters, which indicate relationship with the Rhinoceros. The absence of teeth in the premaxillaries points to the Ruminants. The vertical motion of the jaw points away from the Ruminants, towards the Carnivores. The great expansion of the pelvis, the complete radius and ulna, the shoulder-blade and the hind-foot, are characters which affiliate our animal with the Elephant. The diminutive brain would place it with the pouched Opossum.

"The horns on the maxillaries, the concavity of the crown, and the enormous side crests of the cranium are characters which remove the animal from all living types. We have found the ruins of an animal composed of Elephant, Rhinoceros, Ruminant, Marsupial, and a something unknown to the world of the living. Drawing an outline around the skeleton, we have a long head with little horns on the nose, conical horns over the eyes, and palmate horns over the ears, with pillar-like limbs supporting a massive body nearly eight feet high in the withers and six in the rump. Eliminating from its structure all that relates to the living, so many and such dominant structures remain that we cannot choose for it a name from existing orders. We will call it Uintahtherium[sic], which means, the Beast of the Uintah Mountains."

A pair of antlered elephantine uintatheres appeared in this same book's frontispiece illustration, but this time fleshed out rather than in diagrammatic form, as part of an Eocene panorama of North American mammals. The illustration in question opens this present ShukerNature post, and is also reproduced below, together with its original accompanying caption:

The frontispiece illustration of Gunning's book, featuring a pair of antlered uintatheres (public domain)

The frontispiece illustration of Gunning's book, featuring a pair of antlered uintatheres (public domain)By the end of the 19th Century, however, with many additional fossilised remains having been discovered in the meantime, palaeontological views regarding both the morphology and the taxonomy of the uintatheres had changed markedly. Cope's views concerniing them had been totally rejected in favour of Marsh's, thus promoting the belief still current today that these mammalian behemoths represented a lost ungulate lineage, unrepresented by (and unrelated to) any that are still alive in the modern world.

A rather more modern-looking Uintatherium as illustrated in the Reverend H.N. Hutchinson's book Extinct Monsters (1897)

A rather more modern-looking Uintatherium as illustrated in the Reverend H.N. Hutchinson's book Extinct Monsters (1897)So it was, for instance, that Uintatherium was illustrated in Extinct Monsters (1897) by the Reverend H.N. Hutchinson in much the same manner as it still is now, over a century later, shorn of its velvet-surfaced antlers and with only relatively short and blunt, unbranched horns in their stead, plus much smaller ears, and a conspicuous lack of any probiscidean trunk. The antlered elephant was no more – a non-existent fossil phantom blown swiftly away by a brisk, incoming breeze bearing new discoveries and new ideas borne from a new generation of researchers. 'Twas ever thus.

My How and Why Wonder Book of Wild Animals (1962), containing the first Uintatheriumillustration that I ever saw as a child (© Transworld Publishers)

My How and Why Wonder Book of Wild Animals (1962), containing the first Uintatheriumillustration that I ever saw as a child (© Transworld Publishers)

Published on August 28, 2015 17:27

August 26, 2015

INVESTIGATING THE LOCUST DRAGON OF NICOLAES DE BRUYN - AN ENTOMOLOGICAL ENIGMA FROM THE 16TH CENTURY

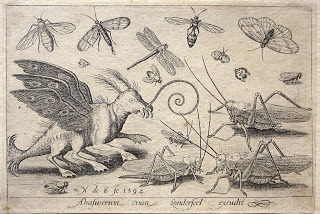

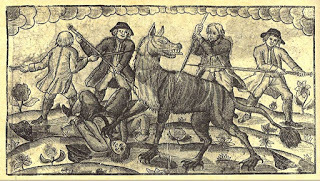

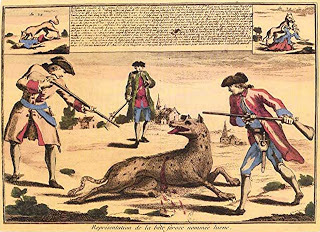

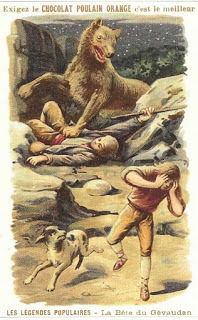

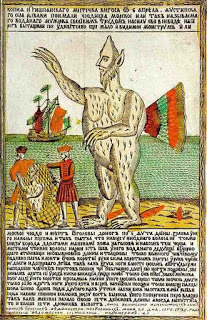

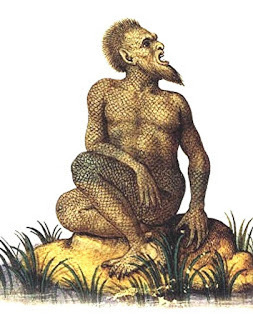

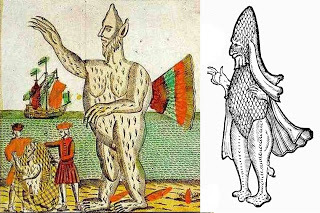

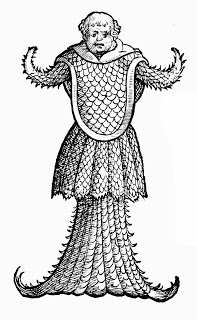

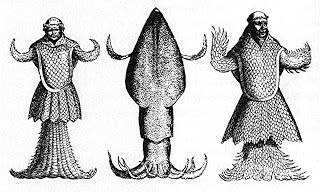

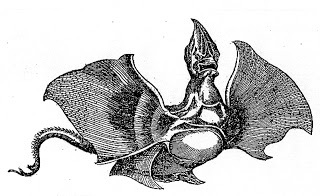

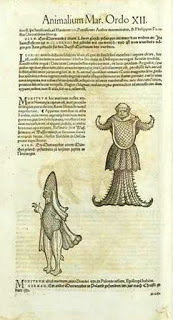

Nicolaes de Bruyn's mystifying engraving from 1594, depicting a wide range of readily-identifiable insects, plus what can only be described as a truly bizarre 'locust dragon' (public domain)

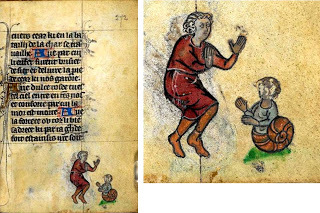

Nicolaes de Bruyn's mystifying engraving from 1594, depicting a wide range of readily-identifiable insects, plus what can only be described as a truly bizarre 'locust dragon' (public domain)As a fervent browser of bestiaries, illuminated manuscripts, and other sources of antiquarian illustrations portraying a vast diversity of grotesque, extraordinary beasts that ostensibly bear no resemblance or relation to any species known to science, I am rarely surprised nowadays by any zoological depictions that I encounter in such sources. A few days ago, however, I was not just surprised but also thoroughly bemused – bewildered, even – by a truly remarkable picture that I happened to chance upon online.

I had been idly cyber-surfing in search of interesting animal images to add to one or other of my two Pinterest albums, when I came upon the engraving to which this present ShukerNature article is devoted, and which opens it above. Yet in spite of my experience with antiquarian images, I had never before seen anything even remotely like the exceedingly bizarre creature occupying much of the left-hand side of this engraving, and its overt strangeness was such that with no further ado I immediately set forth on a quest to uncover whatever I could find out concerning it, and, in particular, to determine what on earth (or anywhere else for that matter!) it could possibly be.

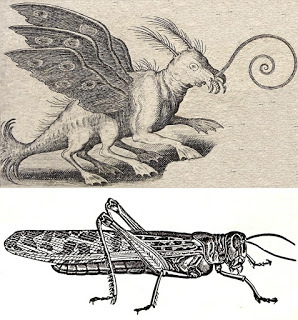

Close-up of de Bruyn's 'locust dragon' (public domain)

Close-up of de Bruyn's 'locust dragon' (public domain)The first pieces of information that I obtained were the identity of the person who had produced this baffling artwork, and its original source. The person was Nicolaes de Bruyn (1571-1656), a Flemish engraver, and as can be seen on this engraving, the date of its production was 1594. Although he is best known for his many biblically-themed engravings and his large engraved landscapes reproducing designs and paintings by other artists, he produced approximately 400 works in total, including a number that featured animals.

The original source of this particular engraving was a series of prints by de Bruyn that depicted various flying creatures. The series was entitled Volatilium Varii Generis Effigies ('Pictures of Flying Creatures of Varied Kinds'), was prepared by de Bruyn in Antwerp, and was first published by Ahasuerus van Londerseel (1572-1635) of Amsterdam. It was subsequently reissued (with van Londerseel's name neatly trimmed off!) by Carel Allard in 1663 (or shortly after – there are conflicting accounts concerning this detail).

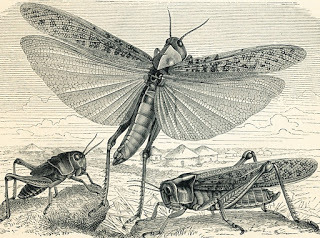

The complete engraving by de Bruyn again, his fantastical locust dragon sharing it with a wide range of accurately-portrayed insects (public domain)

The complete engraving by de Bruyn again, his fantastical locust dragon sharing it with a wide range of accurately-portrayed insects (public domain)What I find so intriguing about de Bruyn's engraving is the juxtapositioning of a fantastical monster in every sense of the term (more like a dragon, in fact, than any real beast), with a number of different types of insect whose depictions are so accurate, so natural, that they readily compare with well-executed 21st-Century equivalents and whose types can be easily identified. Thus, they include long-horned bush crickets, dipteran flies, a ladybird, a panorpid scorpionfly, a large moth, and a narrow-waisted polistid-like wasp.

Yet what if the monster is itself an insect – or is at least intended to represent one? After all, it does possess six legs (albeit ones bearing no resemblance to those of real insects), two pairs of wings (ditto), a pair of bristly antennae, and a long curling butterfly-reminiscent proboscis. But if so, what insect could it be, especially with such a curious tufted tail or abdominal tip, and why has it been portrayed in such a nightmarish, wholly inaccurate fashion, especially when all of the others are so life-like in appearance?

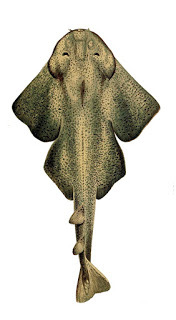

Comparison of de Bruyn's unrealistically-depicted locust dragon (top) with a realistic depiction of a locust (bottom) (public domain)

Comparison of de Bruyn's unrealistically-depicted locust dragon (top) with a realistic depiction of a locust (bottom) (public domain)A copy of this engraving is housed in the collections of Amersterdam's celebrated Rijksmuseum, and when I accessed their record for it (click here ) I was nothing if not startled by the record's claim that the engraving's mystery monster is meant to represent a locust! (The locust species in question is presumably the infamously destructive Old World desert locust Schistocerca gregaria.) Needless to say, however, I've certainly never seen a locust that looks like this, and the Rijksmuseum's record for the engraving contains no clues regarding the raison d'être for its surreal portrayal here.

The only other site encountered by me that offers any thoughts on the matter is Strange Science (click here to see its entry for this engraving). Here, its author notes that in her book Curious Beasts (2013), Alison E. Wright, a curator of prints and drawings at the British Museum, has stated that this image "offers particular insights into the hazards of copying" (an example of it is held in the museum's art collections). In other words, de Bruyn may not have based his engraving upon an actual locust specimen that he had personally seen, but had instead either relied upon a verbal description of one that he had then interpreted extremely imperfectly in visual form, or had simply copied an inaccurate earlier depiction of a locust. In my opinion, however, both of these options are untenable when applied to de Bruyn.

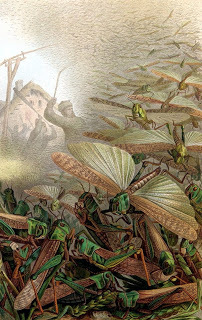

Chromolithograph from 1890 of a locust swarm (public domain)

Chromolithograph from 1890 of a locust swarm (public domain)This is because, as noted earlier here, quite a proportion of de Bruyn's other artworks are biblical in theme. And as plagues of locusts were certainly a biblical occurrence, and are referred to in the Bible's text, one would therefore expect de Bruyn to be familiar with the appearance of this insect. The most famous biblical locust plague was the Eighth Plague of Egypt, sent by God as a curse upon Pharaoh, and documented as follows in the Book of Exodus 10: 12-20:

[12] And the Lord said unto Moses, Stretch out thine hand over the land of Egypt for the locusts, that they may come up upon the land of Egypt, and eat every herb of the land, even all that the hail hath left.

[13] And Moses stretched forth his rod over the land of Egypt, and the Lord brought an east wind upon the land all that day, and all that night; and when it was morning, the east wind brought the locusts.

[14] And the locusts went up over all the land of Egypt, and rested in all the coasts of Egypt: very grievous were they; before them there were no such locusts as they, neither after them shall be such.

[15] For they covered the face of the whole earth, so that the land was darkened; and they did eat every herb of the land, and all the fruit of the trees which the hail had left: and there remained not any green thing in the trees, or in the herbs of the field, through all the land of Egypt.

[16] Then Pharaoh called for Moses and Aaron in haste; and he said, I have sinned against the Lord your God, and against you.

[17] Now therefore forgive, I pray thee, my sin only this once, and intreat the Lord your God, that he may take away from me this death only.

[18] And he went out from Pharaoh, and intreated the Lord.

[19] And the Lord turned a mighty strong west wind, which took away the locusts, and cast them into the Red Sea; there remained not one locust in all the coasts of Egypt.

[20] But the Lord hardened Pharaoh’s heart, so that he would not let the children of Israel go.

In any case, even without the specific biblical art link, locust plagues were sufficiently well known in de Bruyn's day for there surely to be no likelihood that he would be unfamiliar with this insect's appearance. Also, readily identifiable depictions of desert locusts date back thousands of years, exemplified by various portrayals in certain ancient Egyptian sites, such as the following one: