Karl Shuker's Blog, page 33

March 8, 2016

THE YUKON BEAVER EATER, AND GROUND SLOTHS IN NEW ZEALAND?

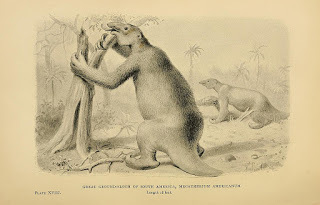

Restoration of Megatherium (Wikipedia/Public domain)

Restoration of Megatherium (Wikipedia/Public domain)When we think of sloths, we generally picture those famously sluggish, dog-sized, tree-dwelling beasts that spend much of their time hanging upside-down from branches in modern-day Central and South America. Millions of years ago, however, there were several additional, very different morphological types – of which the most famous and dramatic were the ground sloths.

Most of these were primarily terrestrial, some were rather bovine in appearance but with shaggy fur, and many were considerably larger than their arboreal relatives. Although principally quadrupedal, ground sloths were capable of squatting erect on their hind legs to browse upon high-level foliage, and their distribution range included not only tropical mainland Latin America, but also North America as well as various of the Caribbean islands.

There were four separate taxonomic families containing ground sloths. The largest species were the megatheriids, typified by Megatherium ('big beast') from the Pleistocene of Patagonia, which attained the size of an elephant (recently split from the megatheriids into their own taxonomic family are the nothrotheriids). At the other extreme were the megalonychids, some being the smallest of all ground sloths, but also including the ox-sized Megalonyx('big claw'), which earned its name from the huge claw on the third toe of each of its hind feet. This latter family also contains today's two-toed tree sloths.

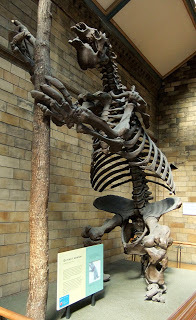

Skeleton of Megatherium (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Skeleton of Megatherium (© Dr Karl Shuker)Intermediate in size between the above groups of ground sloth were the mylodontids - which are of particular cryptozoological interest. For although the last representatives of all types of ground sloth officially died out several millennia ago, reports of mysterious creatures resembling these supposedly bygone beasts have emerged from several different Neotropical locations in modern times - including in particular some compelling evidence to suggest that Brazil may harbour a species of living mylodontid, eluding scientific discovery yet well known to the native people sharing its secluded jungle domain, referring to this cryptid as the mapinguary.

Moreover, certain putative ground sloths living in modern times have been reported from localities outside the Neotropics, including the following pair of hitherto little-known examples.

THE SAYTOECHIN OR YUKON BEAVER EATER

In September 1989, the then recently-formed British Columbia Scientific Cryptozoology Club (BCSCC) was contacted by a Canadian First Nation member named Dawn Charlie concerning a mysterious beast featuring in their oral traditions relating to Yukon's wildlife. The beast in question was referred to as the saytoechin (which translates as 'beaver eater'), and was described as being bigger than even the biggest grizzly bear, and feeding principally upon beavers, which it apparently captured by flipping up their lodges and then seizing the exposed beavers inside. When Native Americans living in the area were shown a book of extinct mammals, they selected an illustration of a ground sloth as the saytoechin, and the most recent reported sighting of one dates from the mid-1980s. As documented in 1990 by BCSCC co-founder Prof. Paul LeBlond in #4 of the Club's newsletter after interviewing Dawn Charlie, the details given by her concerning this sighting are as follows:

The latest report was from Violet Johny, my husband’s sister, who was fishing with her husband and her mother at the head of Tatchun Lake 4 or 5 years ago. An animal came out of the woods, 8 or 9 feet high, bigger than a grizzly bear. It was a “saytoechin” and it was coming towards them. They panicked, fired a few shots over its head and finally managed to get the motor going and took off. There are other reports. There is also a report that a white man shot one in a small lake in that area. Beaver eaters are supposed to live in the mountainous area east of Frenchman Lake.

Although ground sloths are generally thought of as tropical Latin (particularly South) American creatures, before their official extinction at the end of the Pleistocene some species had migrated northwards and had indeed established themselves in parts of North America. At least five genera are currently represented by fossils discovered in various locations here, including a single species, Megaloynx jeffersonii, in Yukon.

Life-sized restoration of Megalonyx jeffersonii in life, at the Iowa Museumof Natural History (© Bill Whittaker/Wikipedia)

Life-sized restoration of Megalonyx jeffersonii in life, at the Iowa Museumof Natural History (© Bill Whittaker/Wikipedia)So in terms of zoogeography alone, a Yukon ground sloth is already known, but obviously a living one is another matter entirely – as is the saytoechin's apparent dietary proclivity for beavers. This is because according to traditional palaeontological belief, all forms of terrestrial non-aquatic ground sloth were exclusively herbivorous. Having said that: in 1996, Drs Richard Fariña and Ernesto Blanco from the Universidad de la República in Montevideo, Uruguay, published a thought-provoking if controversial paper in the Proceedings of the Royal Society, in which they proposed that Megatherium could have used its fearsome claws to overturn, stab, and kill glyptodonts as prey.

From analysing a Megatherium skeleton, Fariña and Blanco discovered that its olecranon (the elbow portion to which the tricepsmuscle attaches) was very short. This adaptation is found in carnivores, and optimises speed rather than strength. These researchers opined that this would have enabled Megatherium to use its claws like daggers, and they suggested that it may have commandeered kills made by the sabre-tooth Smilodon in order to add nutrients to its diet (such behaviour is known as kleptoparasitic). Moreover, based upon the estimated strength and mechanical advantage of its biceps, they proposed that Megatherium could have overturned adult glyptodonts as a means of scavenging or hunting them.

However, this proposal has not gained widespread acceptance. In particular, palaeontologist Dr Paul S. Martin considers it "fanciful", noting that in terms of their dentition, ground sloths lack the carnassials that characterise predators, and that to suggest even that they were scavengers (let alone predators) is a reach. In addition, ground sloth dung deposits studied by him in Arizona's Grand Canyon and also in caves in Nevada, New Mexico, and western Texas contained no traces of bone. So far, therefore, at least as far as the palaeontological world is concerned, the case for carnivorous ground sloths in the past (not to mention in the present) has yet to be convincingly made.

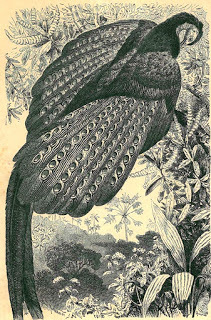

Exquisite vintage illustration of Megatherium, from Extinct Monsters - A Popular Account of Some of the Larger Forms of Ancient Animal Life, 4th ed., 1896, Reverend H.N. Hutchinson (public domain)

Exquisite vintage illustration of Megatherium, from Extinct Monsters - A Popular Account of Some of the Larger Forms of Ancient Animal Life, 4th ed., 1896, Reverend H.N. Hutchinson (public domain)As for the saytoechin: as discussed by Canadian cryptozoologist Sebastian Wang in a BCSCC Newsletter article (fall 2006) documenting this little-known cryptid, although the Native Americans selected a ground sloth from a book of extinct mammals as resembling it there is little else that actually links the two creatures directly. Other, less dramatic identities for it include an unusually large grizzly bear or black bear, plus some cryptozoological ones, such as a bigfoot, or even a surviving short-faced bear Arctodus or giant beaver Castoroides, although the idea of a giant beaver habitually preying upon normal beavers does not seem very likely. As far as I am aware, no specific search has ever been made for the mystifying Yukon beaver eater, so it is surely time for someone to rectify this oversight.

GROUNDS SLOTHS ALIVE AND WELL AND LIVING IN NEW ZEALAND?!

It was cryptozoological archivist Richard Muirhead who kindly brought to my attention what must surely be the most unexpected claim ever made regarding alleged living ground sloths, which can be found in British retired submarine officer Gavin Menzies's book 1421: The Year China Discovered the World(2002). In it, he claims that from 1421 to 1423, during China's Ming dynasty under the Yongle Emperor, the fleets of Admiral Zheng He, commanded by the captainsZhou Wen, Zhou Man, Yang Qing, and Hong Bao, discovered the Northeast Passage, the Americas, Australia, New Zealand, and Antarctica; circumnavigated Greenland; attempted to reach the North and South Poles; and circumnavigated the world a century before before Ferdinand Magellan carried out the first officially-recognised circumnavigation. Not too surprisingly, mainstream historians do not agree with his claims, but such matters lie outside the scope of this present book of mine.

Megatherium

statue in Bautzen, Germany (© Frank Vincentz/Wikipedia

CC BY-SA 3.0 licence

)

Megatherium

statue in Bautzen, Germany (© Frank Vincentz/Wikipedia

CC BY-SA 3.0 licence

)What does lie within its scope, however, is Menzies's suggestion in his own book that on one of their ships the Chinese took aboard some mylodontids captured in Patagonia but that upon reaching New Zealand in c.1421 a pair escaped when the ship was wrecked in Dusky Sound in Fjordland at the southwestern tip of South Island. Moreover, in 1831 a ship from Sydney, Australia, visited Dusky Sound, where two sailors from the ship saw an animal that according to Menzies fitted the description of a ground sloth.

If so, this would indicate that the escaped mylodontids from the 1400s had not only survived in New Zealand but must also have established a population that was still in existence there four centuries later – always assuming of course that the beast seen was indeed a ground sloth, which is a massive assumption to say the least, and even more so when an independent source of information concerning this latter cryptid is examined (see below). Also, the wrecked ship was not Chinese, but an English vessel called the Endeavour, and was wrecked in 1795, not 1421.

A mylodontid depicted on a postage stamp issued by Cambodia in 1994 (public domain)

A mylodontid depicted on a postage stamp issued by Cambodia in 1994 (public domain)Further information concerning this very strange state of affairs was presented in Robyn Jenkin's fascinating book New Zealand Mysteries (1970), which contained the following detailed account of the sailors' mystery beast sighting:

Even more bizarre was a story, also reported to the Collector of Customs in Sydney when the Sydney Packet returned home in 1831. One of the ship's gangs which had been stationed at Dusky Sound told of the discovery of an enormous animal of the kangaroo species.

The men had been boating in a cove in some quiet part of the inlet where the rocks shelved from the water's edge up to the bushline. Looking up they saw a strange animal perching at the edge of the bush nibbling the foliage. It stood on its hind legs, the lower part of its body curving into a thick pointed tail, and when they took note of the height it reached against the trees, allowing five feet for the tail, they estimated it stood nearly thirty feet in height!

The men were to windward of the animal and were able to watch it feeding for some time before it spotted them. They watched it pull down a heavy branch with comparative ease, turn it over and tilt it up to reach the leaves it wanted. When it finally saw them, the animal stood watching the men for a short time, then made one almighty leap from the edge of the bush towards the water's edge. There it landed on all fours but immediately stood erect before making another great leap into the water. The men were able to measure the first jump and found it covered

twenty yards. They watched the animal plough its way down the Sound at tremendous speed, its wake extending from one side of the Sound to the other.

Here again one is tempted to think the rum was talking, and for an Australian going away from home for months on end, what other animal would stir the imagination but a kangaroo? But how much more romantic to think that perhaps they really had seen some prehistoric animal living out its days in the remote fastnesses of the West Coast Sounds.

Romantic it may be, but the mundane reality is that no ground sloth is suspected to have behaved in the highly dramatic manner ascribed to the creature described above, or to have attained its colossal dimensions, which even dwarf those of the mighty Megatherium. In any case, as no comparable accounts appear to have been filed in this dual-island country since that one, it is surely safe to say that if a living ground sloth is indeed discovered one day, it will not be anywhere in New Zealand!

My late mother, Mary Shuker, alongside a life-sized Megatherium statue by Victorian sculptor Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins in London's Crystal Palace Park, photographed in 2010 (© Dr Karl Shuker)

My late mother, Mary Shuker, alongside a life-sized Megatherium statue by Victorian sculptor Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins in London's Crystal Palace Park, photographed in 2010 (© Dr Karl Shuker)My sincere thanks to Sebastian Wang for making available to me his detailed BCSCC Newsletterarticle on the Yukon beaver eater, and to Richard Muirhead for bringing to my attention the remarkable history of New Zealand's alleged ground sloths.

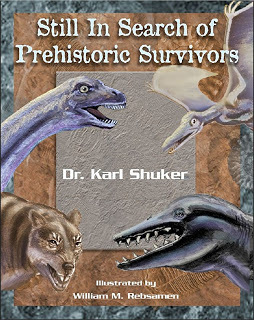

This ShukerNature article is excerpted from my forthcoming book, Still In Search Of Prehistoric Survivors .

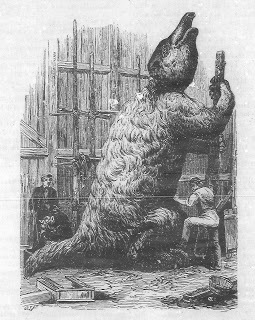

19th-Century engraving depicting the creation of the Crystal Palace Megatherium(public domain)

19th-Century engraving depicting the creation of the Crystal Palace Megatherium(public domain)

Published on March 08, 2016 12:11

February 29, 2016

HOW AN AUSTRALIAN VAMPIRE BECAME THE JERSEY DEVIL

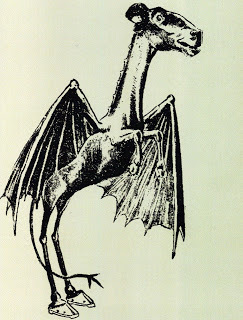

The Jersey devil (© Richard Svensson)

The Jersey devil (© Richard Svensson)For various reasons, it has been quite some time since I last blogged here on ShukerNature. But for many other reasons, which have illuminated my life during the past 24 hours due to the kindness of friends, I realise that it is high time that I did, so here goes. Due to its specific subject, I would like to dedicate this ShukerNature article to one of those friends in particular, as I know that it has been an interest of hers since an early age. And so, Emma Marie, this is for you.

It is rare that a blatant zoological impossibility is not only captured alive but is also placed on public display. Yet during 1909 in Philadelphia, USA, this is precisely what happened...sort of.

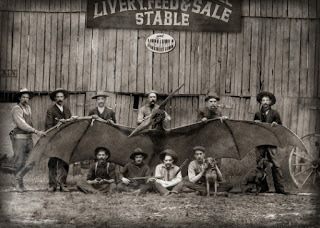

One of the most bizarre and baffling mystery beasts documented in the annals of cryptozoology must surely be the Jersey devil (aka the Leeds devil - according to one yarn, it was supposedly the monstrous offspring of Mother Leeds, a reputed New Jersey witch, after she had been impregnated by the devil in 1735). Alleged sightings of this creature date back as far as the 18th Century, and most commonly occur within an extensive, heavily-forested area of coastal plain stretching across seven counties in southern New Jersey, known as the Pine Barrens. However, there have also been reports emanating from areas far beyond this epicentre – especially during a major 'flap' or outbreak of Jersey devil activity that took place during January 1909, and which stretched as far as Pennsylvania, Delaware, and Maryland.

The creature itself, widely blamed for livestock killings and other depredations, has been described in many different ways, but was generally accorded a pair of leathery, bat-like wings, as well as four limbs (with the clawed front limbs much shorter than the cloven-hoofed hind ones). It was also said to be bipedal, and was often claimed to sport a horse-like head but bearing a pair of ram's horns, a long forked tail, and flashing red eyes. In some encounters, the eyewitnesses alleged that it had emitted a loud blood-curdling scream.

Jersey devil as depicted in the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin, January 1909 (public domain)

Jersey devil as depicted in the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin, January 1909 (public domain)Needless to say, from a zoological standpoint such a creature is an anatomical nonsense, as scientists and other wildlife experts have always steadfastly maintained – thus suggesting that if the Jersey devil is indeed real, it is very different (and far more prosaic) than the evidently much-exaggerated, greatly-embroidered versions that have been claimed by some eyewitnesses down through the ages. Nevertheless, this did not prevent a pair of very canny entrepreneurs from cashing in on the Jersey devil frenzy that took hold during 1909 with what proved to be a very lucrative if entirely fraudulent exhibition purporting to display no less extraordinary an entity than a bona fide, recently-captured, and still very much alive specimen of this sensational(ised) mystery creature.

During the early 20th Century, Philadelphia in Pennsylvania was home to T.F. Hopkins's Ninth and Arch Street Museum, but by the onset of 1909 it was suffering from falling attendances. Anxious to reverse this worrying trend, Norman Jefferies, the museum's publicity manager, hatched a mutually beneficial scheme with animal trainer Jacob F. Hope, one that would boost the museum's popularity and also be financially remunerative to Hope in exchange for his assistance.

As concocted by Jefferies and Hope, a certain story was duly made public about how an extraordinary - and extremely bloodthirsty - animal known as an Australian vampire, formerly in Hope's possession, had recently escaped, and how it was this creature that had been responsible for the bizarre Jersey devil sightings reported in the eastern Pennsylvania/southern New Jersey region during that same time period. Happily, however, according once again to their story, this creature had now been recaptured alive and unharmed, and would be put on display by the museum where it could be seen by one and all, for a viewing fee of course.

Original advertisement for the Jerseydevil exhibition at the Ninth and Arch Street Museumin January 1909 (public domain)

Original advertisement for the Jerseydevil exhibition at the Ninth and Arch Street Museumin January 1909 (public domain)To substantiate this claim, Hope had arranged for a team of a dozen or so specially-hired men who were part of the hoax and acted out the role of trained animal handlers, armed with nets and other implements, to venture forth into a local park one night where the creature was supposedly on the loose, and capture it there. This was duly accomplished when one of the men, perched in a tree, dropped a net over the animal when it passed by underneath. Interested outside observers who may have suspected a fraud had they directly witnessed what was happening were kept outside by a fence ringing the entire park, which was also closed to the public at night anyway.

And what was this ferocious 'Australian vampire' that they had captured in the park? In reality, it was nothing more alarming than a large male red kangaroo Macropus rufus that Jefferies had obtained earlier from a New York animal-dealer colleague and had then 'transformed' into the greatly-feared Aussie mystery beast. This transformation consisted of Jefferies painting a series of vivid green stripes upon its red fur and attaching to its shoulders a pair of lightweight artificial wings, manufactured from thin bronze and covered with rabbit fur. It had then been secretly taken to the park by its supposed pursuers and quietly released there, after which they had promptly – and publicly - recaptured it.

A massive steel cage placed inside the museum's cellar was then set up by Jefferies as the location for his unique specimen's exhibition. Dimly lit, temporarily hidden from outside view by a dropped curtain, and with a gruesome collection of chewed bones strewn across the floor, this was the melodramatic scene in which the creature would take centre stage. Unfortunately, however, the kangaroo did not like its surroundings, and refused to cooperate by putting on any kind of show when tried out by Jefferies in advance of admitting any paying visitors. So he arranged for a boy armed with a long stick bearing a sharp nail at its end to lurk hidden amidst the shadows at the back of the cage.

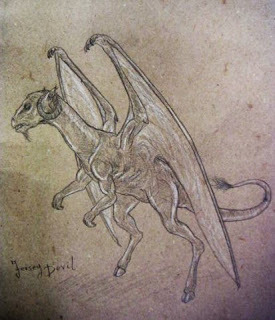

The Jersey devil (© Markus Bühler)

The Jersey devil (© Markus Bühler) As soon as the visitors came in and the curtain rose, the boy would poke the kangaroo surreptitiously with the nailed stick, causing it to leap forward shrieking, its false wings flailing, scaring its audience for an instant before the curtain came down. The shocked audience would then leave, the next visitors would enter, the curtain would rise, and the same brief scene would be enacted all over again, and again, and again – because the exhibition proved very popular, generating much-needed increased takings for the museum, and presumably a handsome payment for Hope too. Only the poor frightened kangaroo, tormented by the nail-embedded stick and confronted by gawping, screaming audiences, gained nothing from the tawdry proceedings.

And how do we know all of this? In 1929, Jefferies publicly confessed to the whole squalid charade.

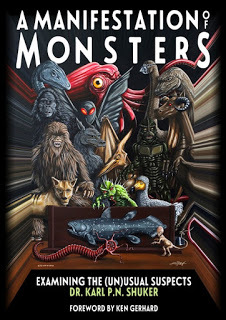

This ShukerNature blog article is excerpted from my book A Manifestation of Monsters .

Published on February 29, 2016 12:34

January 22, 2016

LET'S ALL LOOK OUT FOR THE LAVELLAN

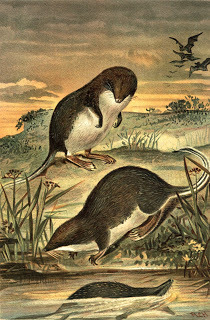

A 19th-Century painting of some aquatic shrews (public domain)

A 19th-Century painting of some aquatic shrews (public domain)In an earlier ShukerNature blog article, I documented a quite small and little-known but thoroughly fascinating if somewhat macabre mystery beast from Scotland known as the earth hound (click here ) – and now, here is a second one, the lavellan.

According to local lore in Caithness and Sutherland, apparently the stronghold of this cryptid, the lavellan is – or was – a rodent with flashing eyes, a disproportionately-large mouse-like or rat-like head, and similar body colouration too. However, it was larger than a rat, had an exceedingly venomous bite, was also a blood-sucker, and inhabited marshes as well as deep water-filled hollows in rivers.

A water vole - one identity that has been proposed for the lavellan (© public domain)

A water vole - one identity that has been proposed for the lavellan (© public domain) Any cattle drinking from a body of water containing a lavellan would invariably die, and, bizarrely, this creature could inflict lethal injuries upon livestock from a distance too, from as far away in fact as approximately 100 ft, though the precise mechanism responsible for this fatal activity is never elucidated in such reports. Yet, paradoxically, if farmers had sick animals, they could be cured if they drank water in which the pelt from a dead lavellan had been dipped.

Interestingly, its name in Scottish Gaelic is also applied to the water shrew Neomys fodiens (which, interestingly, does have a weakly venomous bite) and the water vole Arvicola amphibius, both species having been identified as the lavellan by various authors. Yet the latter creature was supposedly much larger than either of them. Conversely, in John Fleming's book History of British Animals (1828), he claimed that it was likely to be the stoat Mustela erminea, because in early highland lore the stoat supposedly exuded some kind of "foul matter" that was toxic to horses and other animals.

A stoat - another identity proposed for the lavellan (public domain)

A stoat - another identity proposed for the lavellan (public domain)The lavellan's most diligent modern-day investigator is naturalist Raymond Bell, who has memorably dubbed it a 'giant vampire shrew' in various talks and writings that he has prepared on this subject. He has speculated that it may have been at least in part nothing more than a fictitious bogey-beast invented by parents to ward their children away from deep water, or even an attempt to explain away mysterious diseases arising in livestock. However, he also concedes that some bona fide creature might have been at the core of the lavellan legend too, but what that creature was may never be determined.

(As an entertaining digression, 1959 saw the release of a Ray Kellogg-directed science-fiction film that went on to become a highly popular cult movie - The Killer Shrews, in which visitors to a remote island are terrorised by giant mutant shrews. The most famous aspect of the film is that whereas close-ups of the shrews utilise hand-puppets, wider shots of the entire creatures feature coonhounds dressed up to look like shrews! A sequel, Return of the Killer Shrews, was produced in 2012. Both films starred James Best.)

Promotional poster for The Killer Shrews (© McLendon-Radio Pictures Distributing Company – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use educational/review basis only)

Promotional poster for The Killer Shrews (© McLendon-Radio Pictures Distributing Company – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use educational/review basis only)Incidentally, a real-life creature that has been colloquially dubbed a giant killer shrew is Deinogalerix koenigswaldi, which lived during the late Miocene Epoch (11.3-5.6 million years ago) on what was then the Italian island of Gargano, now the Gargano Peninsula. With a skull length of 8 in and a total body length of 2 ft, it occupied the ecological niche filled today by dogs and cats. Yet in spite of its generic name (Deinogalerix translates as 'terror shrew'), it was actually a giant species of gymnure or hairy hedgehog, a group of eulipotyphlan insectivores whose largest modern-day representative is the wonderfully-named moonrat Echinosorex gymnura (click here for a ShukerNature article devoted to this very distinctive mammal).

It is fascinating to consider that the ostensible familiarity of Great Britain's extensively-studied, exhaustively-documented natural history can nevertheless still harbour such riddles as the lavellan and the earth hound. But will their mysteries ever be solved? Perhaps someone reading this present article of mine has the answer to that question and, if so, I very much look forward to hearing from you!

Artistic restoration of Deinogalerix koenigswaldi in life (© Stanton Fink (aka Apokryltaros)/Wikipedia CC BY 3.0 licence)

Artistic restoration of Deinogalerix koenigswaldi in life (© Stanton Fink (aka Apokryltaros)/Wikipedia CC BY 3.0 licence) This ShukerNature blog article was excerpted and expanded from my book The Menagerie of Marvels – further information has been collected by Raymond Bell, who may in due course submit a formal paper on this cryptid to the Journal of Cryptozoology , the world's only peer-reviewed scientific journal devoted to mystery animals, published annually. Look out for Vol. 4, coming soon!

Published on January 22, 2016 19:35

January 20, 2016

QUEMI, SPANISH RACCOON, MINI-SOLENODON, AND NESOPHONTIDS - A QUARTET OF CARIBBEAN CURIOSITIES (AND CRYPTIDS?)

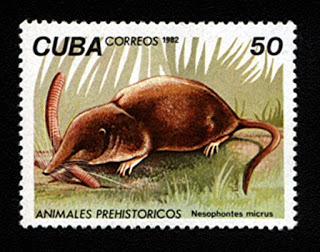

The western Cuban nesophontid Nesophontes micrus as portrayed on a Cuban postage stamp issued in 1982 (© Cuban postal service)

The western Cuban nesophontid Nesophontes micrus as portrayed on a Cuban postage stamp issued in 1982 (© Cuban postal service)Prior to their discovery and colonisation by Europeans, the West Indies in the Caribbean Sea were home to a rich diversity of wildlife, including many unusual endemic forms, most of which, tragically, were soon wiped out by the afore-mentioned colonisation process, due in no small way to the introduction to these islands of a number of non-native predatory species, including rats, domestic cats and dogs, and even mongooses. However, it is possible that some of the endemics survived to later dates than officially confirmed – and in certain cases may still be alive today, awaiting formal rediscovery. In a previous ShukerNature blog article, I documented the strange story of the mysterious Jamaican monkey Xenothrix (click here ). Now, here is a selection of some more of these contentious but extremely intriguing Caribbean creatures that I have investigated and written about.

THE QUEMI QUESTION

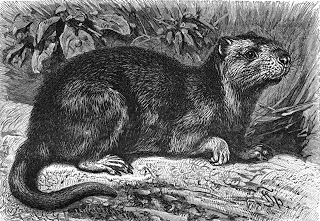

The hutias constitute a series of coypu-related, muskrat-resembling species of rodent found only in the West Indies. Several of these are notorious for having been written off as extinct, only to be unexpectedly rediscovered years later. Indeed, in two separate cases the species in question was discovered alive several years after having been originally described from fossils.

An engraving from 1894 depicting the Cuban hutia (aka the hutia-conga) Capromys pilorides – up to 3 ft long, it is the largest true hutia, but is much smaller than the now-extinct giant hutias (public domain)

An engraving from 1894 depicting the Cuban hutia (aka the hutia-conga) Capromys pilorides – up to 3 ft long, it is the largest true hutia, but is much smaller than the now-extinct giant hutias (public domain)Long ago, however, they shared their islands with some much bigger relatives, loosely termed giant hutias. According to traditional zoological dictum, all of these became extinct well before the West Indies were reached by Europeans, but there is some intriguing evidence to suggest otherwise – the apparent post-Columbus existence here of a curious creature known as the quemi.

This is the name of a mysterious rodent mentioned by explorer Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés in his 16th-Century account of Hispaniola. It was said to be brown in colour, like this island's hutias, but larger in size. Yet following Oviedo's report, nothing more was heard of the quemi – until the 1920s.

That was when some bones of a large, previously unknown species of rodent were discovered in a cave near a plantation at St Michel, Haiti, on Hispaniola. After studying them, Dr Gerrit Miller of the Smithsonian Institution identified their owner as a representative of Oviedo's obscure quemi, and in 1929, within his formal description of the bones, Miller named their species Quemisia gravis. Remains have since been found in the Dominican Republic on Hispaniola too. Moreover, this species was apparently a traditional item of food for the native Hispaniolans, as its limb bones have been found in early kitchen middens.

Today, the quemi is also known as the twisted-toothed giant hutia - but whatever happened to it? Researchers believe that this interesting rodent died out soon after the arrival on Hispaniola of the Spaniards, and certainly no later than the 16thCentury's close – yet another irreplaceable island endemic that simply couldn't compete with the arrival of humankind and its ever-attendant array of introduced species, particularly the black rat.

A taxiderm hutia specimen (Public domain)

A taxiderm hutia specimen (Public domain)Having said that, in 1989 one researcher speculated that Oviedo's description of the quemi may not have been a reference to Quemisia gravis after all, but instead to Plagiodontia velozi (aka P. ipnaeum). This is a now-extinct species of Hispaniolan hutia known as the Samana hutia, whose remains have been found with those of black rats, thus suggesting that it was still alive when the first Europeans and their stowaway rodent entourage first reached this Caribbean island in 1492.

The Samana hutia may also (or alternatively) be the identity of a second mystifying, still-unclassified Hispaniolan rodent. Known locally as the comadreja, this cryptid allegedly survived here until the 20thCentury.

THE SPURIOUS SPANISH RACCOON

Yet another Caribbean mystery mammal that may be hutia-related is the so-called 'Spanish racoon' mentioned in Dr Patrick Browne's The Civil and Natural History of Jamaica (1756). Including it in a listing of six species of mammal that he collectively termed Mus (which is the genus housing the common, typical species of mouse within the taxonomic family Muridae), Browne claimed that this creature was not native to Jamaica but was frequently imported there from Cuba (where it was very common). He stated that it sported fairly rough fur; rabbit-like eyes, teeth, and lips, but wider nostrils, and shorter, smaller ears; plus a straight, tapering, hairy tail; and that it exhibited a vegetarian diet.

A North American raccoon, which certainly does not match the decidedly rodent-reminiscent description given by Browne for the so-called Spanish raccoon (public domain)

A North American raccoon, which certainly does not match the decidedly rodent-reminiscent description given by Browne for the so-called Spanish raccoon (public domain)Interestingly, raccoons did formerly exist in Jamaica (and Cuba), but they were exterminated there by Spanish colonists who hunted them for their meat, with the last sightings reported in 1687 (and they were wiped out even earlier in Hispaniola, by 1513). However, no raccoon species corresponds with the verbal portrait by Browne given above, or is vegetarian, and it would be decidedly odd to categorise a bona fide raccoon as a mouse. Conversely, the Spanish raccoon as described by Browne was evidently a rodent. Consequently, when referring briefly to this enigmatic animal within his standard work Extinct and Vanishing Mammals of the Western Hemisphere (1942), American mammalogist Dr Glover M. Allen speculated that "it was probably the larger Cuban hutia, Capromys pilorides". Although this identification is certainly very plausible, it has never been formally confirmed, so the mystery of Browne's 'Spanish racoon' remains officially unresolved.

MARCANO'S MISSING MINI-SOLENODON

Looking like large rats with very long, attenuated snouts, solenodons may not seem very prepossessing in appearance, but they have great zoological significance, as they represent the last of an ancient line of insectivorous mammals stretching back 30 million years.

Taxiderm specimen of the Haitian solenodon (© Markus Bühler)

Taxiderm specimen of the Haitian solenodon (© Markus Bühler) Now wholly confined to the West Indies, there are just two surviving species - the Hispaniolan solenodon Solenodon paradoxus, and the Cuban S. cubanus (of which only its black-and-white subspecies S. c. poeyana is still extant; no specimen of its buff-headed type subspecies S. c. cubanus has been reported since 1944). Both species are extremely rare, and have been written off as extinct on several occasions in the past, as chronicled in my three books on new and rediscovered animals.

19th-Century engraving of the Cuban solenodon's distinctive black-and-white subspecies (public domain)

19th-Century engraving of the Cuban solenodon's distinctive black-and-white subspecies (public domain)A smaller and more obscure third species of solenodon, Marcano’s solenodon S. marcanoi, is known only from geologically-recent skeletal remains, found in the Dominican Republic on Hispaniola, whose species was formally described and named in 1962. Because they were found in association with remains of Rattus rats (introduced onto Hispaniola by European settlers), it is believed that this diminutive solenodon persisted beyond Hispaniola’s initial European colonisation by Columbus during the late 1400s, but was wiped out soon afterwards by the rats once they arrived aboard Spanish vessels during the early 1500s,

NOSEING AROUND FOR NESOPHONTIDS

Another family of unusual insectivores (or, to be precise, eulipotyphlans) exclusive to the West Indies consisted of the nesophontids. These were shrew-like mammals of varying sizes (one of the 6-12 currently-recognised species was as large as a chipmunk) that supposedly died out during the 17th Century on the cluster of Caribbean islands (Cuba, Hispaniola, Puerto Rico, and two of the Cayman Islands) constituting their homeland. In 1930, however, some nesophontid bones and tissues extracted from a mass of owl pellets discovered in the Dominican Republic, Hispaniola, were found to be so fresh that it seemed possible that the individual(s) from which they had derived had been killed only a short time before. This encouraged Dr Gerrit Miller to speculate that some nesophontids may still exist after all, but radiocarbon-dating of such fresh-seeming pellets has so far failed to substantiate any 20th-(or 21st-) Century survival.

Representation of the Puerto Rican nesophontid Nesophontes edithae (© Jennifer Garcia/Wikipedia CC By-SA 3.0 licence

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/legalcode

)

Representation of the Puerto Rican nesophontid Nesophontes edithae (© Jennifer Garcia/Wikipedia CC By-SA 3.0 licence

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/legalcode

)Nevertheless, certain researchers have suggested that some nesophontids may indeed have persisted until at least the early 1900s. Having said that, a 10-week survey of West Indian mammals conducted on Hispaniola and Puerto Rico by Jersey Wildlife Preservation Trust researchers during the 1980s failed to uncover any evidence of current survival for them. Nevertheless, given the extremely elusive nature of their solenodon relatives on Hispaniola and Cuba, perhaps there may come a time when the nesophontid family will indeed be resurrected.

This ShukerNature article consists of excerpts from my books The Menagerie of Marvels and The Encyclopaedia of New and Rediscovered Animals .

Published on January 20, 2016 18:20

January 2, 2016

MONKEYS IN AUSTRALIA? REVISITING A FORGOTTEN FURRY MYSTERY DOWN UNDER

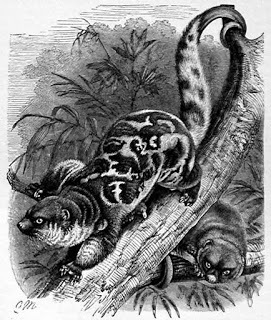

An early lithograph of the spotted cuscus – the identity of Cape York Peninsula's mystery monkeys? (public domain)

An early lithograph of the spotted cuscus – the identity of Cape York Peninsula's mystery monkeys? (public domain)Zoologically speaking, Australia is most famous for its marsupials (pouched mammals) and monotremes (egg-laying mammals). It does contain a number of native species of placental (higher) mammal too – the predominant mammalian category everywhere else in the world – mostly rodents and bats, but also including the famous Australian wild dog or dingo. Since this island continent was colonised by humans, however, many non-native placental mammals have been introduced here as well, such as domestic cats and dogs, deer, sheep, cattle, foxes, and rabbits. However, there is no official confirmation that Australia has ever been home to monkeys – which is why an outbreak of monkey reports here during the early 1930s is so intriguing, and, although all-but-forgotten today, has never been satisfactorily resolved.

One of the world's last unspoiled wildernesses, boasting a rich abundance of relatively undisturbed habitats including tropical rainforest and wooded savannahs, Cape York Peninsula is a vast, remote triangle jutting northward from northernmost Queensland into the Torres Strait, separating Australia at that point from New Guinea. If mystery animals could exist undetected anywhere in northern Australia, this is where they would be. And sure enough, in autumn 1932, after a party of bold, adventurous gold prospectors had penetrated this secluded realm, they came back home to Townsville with tales of having encountered there some very strange and, for Australia, extremely unexpected creatures – monkeys. And not just a few monkeys either. According to a remarkable report appearing on 19 September 1932 in an Adelaide, South Australia, newspaper entitled the News, "several thousand" of these mystifying creatures had been seen (though this count was reduced to "hundreds" further down in that same report).

The prospectors had journeyed to the region of Cape York Peninsula situated between the Lockhart and Pascoe Rivers, 130 miles south of Cape York and 40 miles from the coast. This area's almost impenetrable terrain, apparently having never before been explored by Westerners, was so densely packed with large trees bearing great quantities of red nuts that they "had to fight their way" through, and it was here where they encountered the monkeys, after having initially being alerted to their existence by natives. The monkeys were inhabiting an area 60 miles long by 30 miles wide, and according to the prospectors they "seemed to be of the Malayan breed, about the size of an average dog, and weighing about 30 lb".

Cape York Peninsula monkeys report in the News (Adelaide), 19 September 1932 - click to enlarge for reading purposes (public domain)

Cape York Peninsula monkeys report in the News (Adelaide), 19 September 1932 - click to enlarge for reading purposes (public domain)Versions of this report simultaneously appeared in a number of other Australian newspapers too, including one in Queensland's Townsville Daily Bulletin claiming that the monkeys seen by the prospectors were in groups of about 15-20 individuals, and that there were "numerous" such groups. These reports were followed by a second account emerging just a day later, on 20 September, from a gold prospector named R. King. As again covered in a wide range of newspaper reports across Australia, he stated that he had not only encountered some monkeys but had even shot a couple of them while exploring one particular area of Cape York Peninsula. According to a report that appeared in the Maryborough Chronicle on 20 September 1932, documenting King's testimony:

The area in which King located the animals is south-east of the Batavia goldfield, embracing the McIlwraith Range [a rugged granitic plateau], the area being about 30 miles wide and extending along the peninsula for approximately 60 miles. King said today that he journeyed on the western side of the range searching for gold. There was nothing there that suggested human beings had ever been in that locality. Progress was difficult with horses being impeded by sugarcane grass growing to enormous heights, in some instances up to 15 feet. In this scrub the prospector saw mobs of monkeys frequently during his four or five weeks' stay. They were generally in parties from 15 to 25.

But that was not all:

Though he could not get closer than rifle range he shot a couple during his stay. Observations he made seemed to indicate that the male was much larger than the female and the largest would not exceed about 30lb.

If only King had brought back the body of one of the shot monkeys for scientific examination. Having said that, however, carrying what would have been a rapidly-decomposing, stinking carcase back with him through difficult terrain in the humid conditions prevalent in this locality would not have been the easiest or most pleasant of tasks, so I can certainly understand why he didn't do so!

Nevertheless, according to an article published on 1 October 1932 by a Cairns, Queensland, newspaper entitled the Northern Herald, King was willing to self-finance a two-man expedition, consisting of himself and a scientific representative, back to the location where he'd seen the animals, provided that "a substantial reimbursement were guaranteed on production of the specimens". As far as I am aware, however, no such expedition was ever launched, so presumably King did not receive any such guarantee.

Well worth recalling at this point is that during the second half of the 19th Century, a number of acclimatisation societies sprang up all over Australia. Their shared goal was to introduce into the wild a vast diversity of exotic, non-native species that their members considered would be beneficial for food, for cultural exchange purposes with other countries, or, in some cases, for purely aesthetic reasons (i.e. they were attractive species, or were familiar ones that reminded the societies' members of Europe). In order to achieve this, the societies sought to create captive-breeding colonies from which releases into the wild could subsequently be carried out until self-sustaining populations had established themselves there.

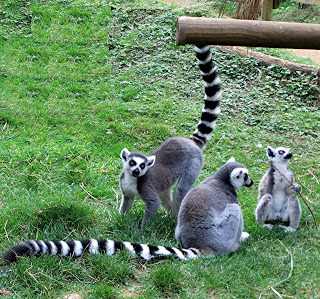

Madagascan ring-tailed lemurs roaming wild in Australia? It nearly happened! (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Madagascan ring-tailed lemurs roaming wild in Australia? It nearly happened! (© Dr Karl Shuker)Among the mammalian species on their lists of proposed releases were such geographically and taxonomically diverse creatures as South American agoutis, African elands, Madagascan ring-tailed lemurs – and several species of monkey. Indeed, in 1861, Edward Wilson, the founder of Victoria's acclimatisation society, wrote to this Australian state's governor requesting that monkeys be released into the Victorian bush: "…for the amusement of the wayfarer, whom their gambols would delight as he lay under some gum tree in the forest on a sultry day". Happily, however, for the survival of Australia's unique, irreplaceable endemic fauna, very few of these alien species bred successfully even in captivity at the societies' various breeding centres (let alone in the wild). Consequently, most of the planned releases never took place, and I am not aware of any record of official monkey releases having occurred anywhere on this continent. But might there have been some unofficial, undocumented, unpublicised acclimatisation efforts involving monkeys that were successful, with Cape York Peninsula being deemed an ideal locality for such creatures to live and thrive (which, indeed, it is)? Yet if not, what other explanations can be offered for the gold prospectors' sightings here?

During the weeks that followed the two prospector accounts being widely disseminated by the Australian media, several additional articles were also published, containing opinions regarding the possible identity of Cape York Peninsula's supposed monkeys, as proffered by a range of scientists and others who were variously interested in or dismissive of this mystifying affair. But once its initial novelty had worn off, however, and (as always happens with ephemeral subjects like this) the media began looking elsewhere for curiosities to publicise, the Peninsula's enigmatic primates vanished from the headlines, and eventually from all but the most tenacious memories within the zoological community too.

Indeed, if referred to at all nowadays (which it seldom is), this entire episode is normally dismissed as the outcome of a regrettable misidentification by the gold prospector eyewitnesses, mistaking one or other of two already-known types of marsupial for monkeys. As will now be shown here, however, neither of these 'official' identities stands up to close scrutiny. Having said that, there seems little doubt that some form of creature wasencountered (and in some numbers) amid this peninsula's remote backwaters, so what might it have been?

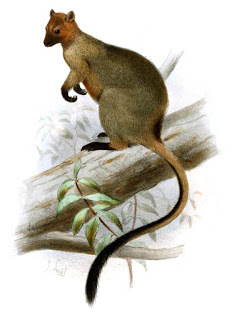

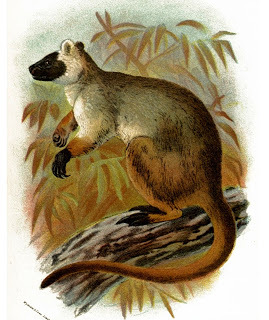

An 1884 lithograph of Lumholtz's tree kangaroo (public domain)

An 1884 lithograph of Lumholtz's tree kangaroo (public domain)When the story of the alleged monkeys in the Peninsula broke, two different but equally popular mainstream identities were variously proposed for them by a number of different authorities. One of these identities was some form of tree kangaroo – as suggested, for instance, by Ludwig Glauert, then Curator of Perth Museum.

Two species are native to Australia, and both occur in a small portion of Cape York Peninsula's easternmost basal region. The smaller and more common of these is Lumholtz's tree kangaroo Dendrolagus lumholtzi, a rainforest-inhabiting species predominantly black and grizzled grey in colour, with somewhat short limbs but an exceedingly long tail, and only weighing up to around 20 lb maximum. Larger and rarer here is Bennett's tree kangaroo D. bennettianus, dark chocolate-brown above and fawn below, with longer limbs, a very long tail, and weighing up to 30 lb in adult males (females are much smaller). It inhabits both mountain and lowland tropical rainforest, but is notoriously elusive.

An 1894 lithograph of Bennett's tree kangaroo (public domain)

An 1894 lithograph of Bennett's tree kangaroo (public domain)In terms of dimensions, maximum-sized Bennett's tree kangaroos are comparable to the largest 30-lb alleged monkeys as estimated by King and the other prospectors; but in terms of morphology, neither species of Peninsula tree kangaroo is particularly simian. Moreover, whereas both species have very long, noticeable tails, no mention of tails occurred in either of the two gold prospector reports – indicating, perhaps, that the creatures that they encountered were either tailless or only possessed short, inconspicuous tails?

In addition, whereas all Old World monkeys are diurnal, as the creatures encountered by the prospectors clearly were too, both of these tree kangaroo species are nocturnal, so they wouldn't have been readily perceived or even met with by their eyewitnesses, and neither species occurs in large groups or parties like the creatures sighted anyway (Lumholtz's occurs in small, loose-knit reproductive groups of just 3-5 adult members). Also, if they had indeed been nothing more than tree kangaroos, the region's native inhabitants would surely have known this, and therefore would not have specifically called the prospectors' attention to them.

Instead, and even before his own first-hand encounter with the alleged monkeys, King had already been informed by aboriginals inhabiting the Daintree River area that monkeys lived in the Peninsula. However, he had discounted their claims, assuming that the creatures that they were referring to were simply tree kangaroos – until he saw them with his own eyes, and realised that they were not. This also demonstrates that King knew what tree kangaroos looked like, and therefore would not have been confused by them.

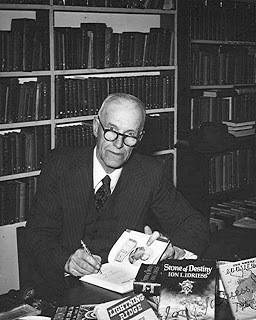

Ion Idriess (public domain)

Ion Idriess (public domain)At the time of the media reports concerning the Cape York Peninsula monkeys, one of the few Westerners to have explored sizeable portions of this region was Australian writer Ion Idriess. When media reporters asked his opinion as to these mystery animals' possible identity, he speculated that they may have been either a species of tree kangaroo or, his personal preference, a very large phalanger – which brings us to the second popular mainstream identity offered for the Peninsula monkeys.

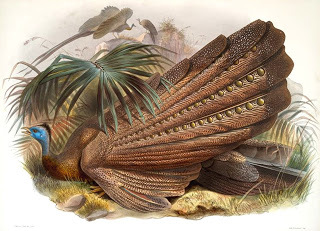

Phalangers are arboreal marsupials closely related to the possums and sugar gliders, and the largest phalangers are the cuscuses (the biggest species of which is New Guinea's black-spotted cuscus Spilocuscus rufoniger, up to 4 ft long and weighing as much as 15 lb). Although cuscuses are predominantly found in New Guinea and on certain Indonesian islands close by, two New Guinea species also occur in Australia's Cape York Peninsula.

Taxiderm specimen of the spotted cuscus (© Markus Bühler)

Taxiderm specimen of the spotted cuscus (© Markus Bühler)Of these two, the species less likely to explain this region's supposed monkeys is the well-named spotted cuscus S. maculatus, because in the male its thick brown fur is indeed handsomely and very noticeably patterned with irregular white spots and blotches, which sometimes are so extensive that the animal appears white with brown blotches (females are unspotted). This striking characteristic is of course conspicuous only by its absence in the prospectors' monkey accounts, yet due to its eyecatching nature it would surely have been reported by them if it had indeed been exhibited by the monkeys (some of them would certainly have been males).

The second cuscus species native to this peninsula is the grey cuscus Phalanger mimicus (which is closely related, and similar in overall appearance, to the more familiar ground cuscus P. gymnotis). Its woolly unpatterned fur is grey-brown dorsally and laterally, and off-white ventrally, with a brown mid-dorsal stripe extending along its spine from its ears to its rump.

Ground cuscus (public domain)

Ground cuscus (public domain)As with the tree kangaroos, however, both of these cuscus species are predominantly nocturnal, do not occur in large groups (they are generally solitary animals), and are so cryptic that they are seldom spied even by the region's aboriginals. They are also sluggish and slow-moving, unlike typically active, agile monkeys. Additionally, neither of them attains anything like a weight of 30 lb; on the contrary, no bigger than typical domestic cats they rarely exceed 8 lb in the wild (sometimes more in captivity), with the spotted cuscus being slightly bigger than its grey-furred relative.

In view of such notable discrepancies between cuscuses and monkeys, I was nothing if not surprised, therefore, to discover, via a brief single-line reference to the Cape York Peninsula monkey saga contained in her book Possums: The Brushtails, Ringtails and Greater Glider(2001), that Anne Kerle considered that the grey cuscus was "undoubtedly" the origin of the monkey reports. Further back in time, but no less surprising, was that in his book Furred Animals of Australia(8th edition, 1965), Australian zoologist Ellis Troughton stated that spotted cuscuses have "a remarkably monkey-like appearance" and that this species may therefore have inspired the Peninsula monkey reports (notwithstanding this cuscus's unmissable spotting?). Moreover, an old, now-obsolete colloquial name for the grey cuscus is 'monkey cuscus', and another, even older (and taxonomically inaccurate!) name for it is 'monkey opossum'. (Taxonomically, the term 'opossum' is restricted to the didelphid marsupials of the Americas.)

I find these allusions to the supposed monkey-like appearance of cuscuses to be very perplexing, even bizarre. For as someone who has seen living cuscuses at close hand in captivity while visiting Australia, I can readily affirm that they do not look like monkeys at all – being far closer in appearance to certain lemurs among the primates. Nor am I alone in that view, because it was also expressed back in the 1930s by various commentators in relation to the possible identity of the Peninsula monkeys.

A decidedly (and accurately) lemurine representation of the spotted cuscus in an 1890s engraving (public domain)

A decidedly (and accurately) lemurine representation of the spotted cuscus in an 1890s engraving (public domain)For instance: in an article focusing upon the Peninsula's cuscuses and published by the Queenslander newspaper on 22 August 1935, the columnist 'Wanderer' uncompromisingly stated: "How the cuscus came to be called the "monkey opossum" I cannot say, but the name is not appropriate, for the creature is neither monkey-like in appearance nor habits". Similarly, in an Adelaide Advertiser article of 10 December 1932, its author, Donald Thomson, who was leading an expedition in the Cape York district, bluntly confirmed that when a cuscus is closely examined: "…it does not look at all like a monkey". Amen to that!

Equally, as with the tree kangaroos, the Peninsula aboriginals would have been familiar with the cuscuses living there, so surely they would not have attempted to portray them to the prospectors as anything other than cuscuses. Also of note is that when Australian naturalist-prospector William McLennan suggested to King that what he had seen were cuscuses, King denied this, stating that he was familiar with cuscuses, and that what he had seen were monkeys, not cuscuses.

No other native mammals in Cape York Peninsula look like monkeys either, so if we sensibly choose to dismiss as implausible the premise that not only the prospectors but even the native aboriginals had all been extremely unknowledgeable regarding the animals encountered by them there and even less adept at identifying them correctly, the true nature of these supposed monkeys remains a mystery – unless of course they really were monkeys! Yet if this is true, how can the presence of such blatantly non-native animals in the wilds of Australia be explained?

William H.D. Le Souef (public domain)

William H.D. Le Souef (public domain)During his newspaper account, prospector King opined that these reputed monkeys had come from Malaya during the early days of trading between southeastern Asia and Australia, and had remained in reclusive anonymity ever since within the Peninsula's dense scrub where Westerners had not penetrated prior to the recent forays there by himself and the other prospectors. This notion was echoed by Ion Idriess, who conceded that it was plausible that a few monkeys had originally escaped ashore from trading steamers or from wrecks, had thrived and bred in the Peninsula, and had eventually given rise to a self-sustaining population there. Even the eminent Australian naturalist William H.D. Le Souef from Sydney's Taronga Park Zoo stated that it was quite possible that the prospectors' information was correct.

But even if this were so, what kind of monkey might they have been? King and the party of prospectors variously made comparisons between the Peninsula creatures and Malayan monkeys, and suggested a Malayan origin for them, and it is true that 11 different species of monkey collectively exist in mainland Malaysia and in its two states on Borneo (Sabah and Sarawak). They fall into two categories – very slender, long-limbed, long-tailed langurs or leaf monkeys (7 Malaysian species), and sturdier, shorter-limbed, often only short-tailed macaques (4 Malaysian species, following the recent taxonomic splitting into two of the pig-tailed macaque). Moreover, both of these monkey types socialise in large groups (sometimes extremely large in the case of macaques), just as reported by the prospectors for the creatures that they saw.

An 1800s lithograph of a langur or leaf monkey (public domain)

An 1800s lithograph of a langur or leaf monkey (public domain)Confined to Borneo, the largest Malaysian langur, the famous proboscis monkey Nasalis larvatus with its huge grotesque nose in the adult male, can surely be eliminated from consideration straight away. This is because not only is its nasal appearance so distinctive that the prospectors would have assuredly mentioned it specifically in their accounts, but males can exceed 60 lb in weight, i.e. more than double the size estimated by the prospectors for even the largest of the creatures that they saw. Other Malaysian langurs, conversely, such as the silvery (crested) langur Trachypithecus cristatus and the spectacled langur T. obscurus, only attain half the weight claimed by the prospectors for the largest of their alleged monkeys (little more than a third in the white-fronted langur Presbytis frontata), and (like tree kangaroos) they possess extremely long, visible tails.

Macaques native to Malaysia include the crab-eating macaque Macaca fascicularis and the two near-identical pig-tailed macaque species M. leonina and M. nemetrina. Unlike a number of other macaques, however, the crab-eating macaque does have a long tail, and males attain a maximum weight of only around 20 lb. Yet, interestingly, this is a notable invasive species, having been successfully introduced to a number of non-native territories where it now thrives, including New Guinea, which as noted earlier is immediately to the north of Australia's Cape York Peninsula, separated from it only via the Torres Strait.

Crab-eating macaque (public domain)

Crab-eating macaque (public domain)During the course of history, many large species have spread from one region to another via rafting across stretches of water on floating debris, vegetable mats, etc – could specimens of this macaque species have done the same, from New Guinea to Cape York Peninsula? The pig-tailed macaques have only a fairly short tail, but their males are slightly smaller in size than those of the crab-eating macaque, as are those of the stump-tailed macaque M. arctoides, which has an even shorter tail.

A pig-tailed macaque (public domain)

A pig-tailed macaque (public domain)A third option is also worth a consideration – might these so-called monkeys have actually been apes, specifically gibbons? After all, laymen frequently refer to gibbons (and other apes too) as monkeys. Four species exist in Malaysia, of which the siamang Symphalangus syndactylus is much too big, but the other three – the agile gibbon Hylobates agilis, lar gibbon H. lar, and Müller's Bornean gibbon H. muelleri – are smaller and, like all gibbons, are tailless.

When I first read the two prospector accounts describing the alleged monkeys witnessed by them, however, I immediately thought of macaques, in terms of both their appearance and their large groups. These monkeys also have a much closer affinity with humans than langurs and gibbons, being frequently kept as pets aboard ships, as well as used in scientific research (the famous rhesus monkey Macaca mulatta, a commonly-used laboratory species, is a macaque). Consequently, if we assume that the Peninsula mystery beasts were real, and that they were indeed monkeys, perhaps they were macaques that had escaped or been released there by Malay traders visiting northern Australia, with their body size either exaggerated by the prospectors or, with no notable predators in this secluded region, larger than normal specimens having subsequently arisen. Of course, the prospectors' claim of seeing "several thousand" of these monkeys is worrying with regard to their account's authenticity, but this may well be due to journalistic hyperbole, because "hundreds" was used further down in the same newspaper articles covering their account.

Rhesus monkey (public domain)

Rhesus monkey (public domain)Today, approximately half of Cape York Peninsula has been given over to cattle grazing, but much of the remaining half is preserved as a national park, with its virgin wilderness still a haven of largely undisturbed tranquillity for its wildlife. Is it conceivable, therefore, that a colony of monkeys genuinely existed here less than a century ago, having descended from some specimens originating from Malay ships and/or rafting across from New Guinea (or possibly even stemming from some unpublicised, covert acclimatisation-based introductions)?

If so, and, with nothing having occurred during the interim period to have eradicated wildlife in much of this vast, scarcely-penetrable locality, might they still be there today?

An 1890s lithograph of Lumholtz's tree kangaroo (public domain)

An 1890s lithograph of Lumholtz's tree kangaroo (public domain)

Published on January 02, 2016 09:58

December 17, 2015

FROM STAR WARS TO SMITHFIELD - THE CURIOUS CASE OF THE MEDIEVAL YODA MONK

The Yoda lookalike figure from the Smithfield Decretals (public domain)

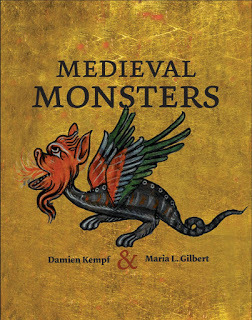

The Yoda lookalike figure from the Smithfield Decretals (public domain)The long-awaited latest Star Wars film – Episode VII: The Force Awakens – was released this week, so it seems timely to upload onto ShukerNature the following article of mine that I wrote a while back after purchasing the book Medieval Monsters but never got around to doing anything with, until now…

Long ago, in a galaxy far far away – or, more precisely, in March 2015 on p. 5 of a then newly-published book entitled Medieval Monsters , written by medieval historian Damien Kempf and art historian Maria L. Gilbert – an extraordinary illustration appeared that swiftly attracted considerable media attention, spawning all manner of newspaper and online articles during mid-April. The illustration in question was a figure from an illuminated manuscript dating from the 14th Century – a figure reproduced at the beginning of this ShukerNature blog article and which, as noted by those numerous media articles, just so happened to bear a striking resemblance to none other than Yoda, the venerable Jedi Grand Master from the Star Warsmovie franchise!

Medieval Monsters

– a fascinating, sumptuously illustrated survey of monstrous entities depicted in illuminated manuscripts (© Damien Kempf and Maria L. Gilbert/British Library)

Medieval Monsters

– a fascinating, sumptuously illustrated survey of monstrous entities depicted in illuminated manuscripts (© Damien Kempf and Maria L. Gilbert/British Library)Yoda first appeared as a (relatively) sprightly 900-year-old in The Empire Strikes Back – produced by Lucasfilm Ltd, released in 1980 and constituting the second film in the ongoing Star Wars series. In contrast, his Middle Ages doppelgänger appeared over 600 years earlier, in the Smithfield Decretals (a colloquial name deriving from its earliest known provenance, the Augustinian priory of St Bartholomew's at Smithfield, its official title being the Decretals of Gregory IX with glossa ordinaria [i.e. commentary] of Bernard of Parma). This is a parchment codex in Latin, which dates from c.1300-1340, and can be found in the British Library listed as Royal MS 10 E IV (with the mystery figure appearing on f. 30v). Written in southern France (probably Toulouse), the original manuscript arrived in London during the early 1300s where numerous marginal illustrations were added. It was presented to the British Museum in 1757 by King George II as part of the Old Royal Library.

The likeness of the strange entity in this early historical manuscript to Yoda was not actually commented upon in Medieval Monsters, but was spotted by British Library curator Julian Harrison, who duly documented it in his blog Medieval Manuscripts (in a guest post on this same blog for 14 April, the authors of Medieval Monsters did allude to it in a whimsical poem about their book's contents). Looking at this enigmatic figure, there is unquestionably a similarity, from its monk-like attire, and long ears sticking out at right angles from its head, to its spiky hands, greenish skin, and facial expression. Consequently, once the various media articles aired online, it was not long before fevered speculation arose as to whether Yoda was indeed based upon the enigmatic image from the Smithfield Decretals.

The mystifying monk-like entity from the Smithfield Decretals (left) alongside Yoda as seen in The Empire Strikes Back (right) (public domain/(© Lucasfilm Ltd-20thCentury Fox – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use educational/review basis only)

The mystifying monk-like entity from the Smithfield Decretals (left) alongside Yoda as seen in The Empire Strikes Back (right) (public domain/(© Lucasfilm Ltd-20thCentury Fox – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use educational/review basis only)However, the designer of Yoda's distinctive appearance, the late Stuart Freeborn (d. 2013), a British motion picture make-up artist, always stated that the character's face was based upon his own, and that his eyes were inspired by those of Einstein in order to give them a wise but kindly look. Moreover, it seems highly unlikely to say the least that back in the pre-internet years of the 1970s when he was creating Yoda's character, Freeborn was even aware of this exceedingly obscure centuries-old French manuscript, let alone had access to a copy of it.

So if not a prototype for Yoda, what exactly was that medieval manuscript-featured monk with the big ears meant to represent? Some articles erroneously claimed that this orange-robed figure appeared in a retelling of the biblical story of Samson present within the Smithfield Decretals, but in reality the latter manuscript is a collection of canon law composed during the 13th Century that served as an addition to the Decree of Gratian, the main collection of canon law composed during the 12th Century. (Decretals are actually collections of papal letters that compile decrees on church law.) Consequently, as postulated on the Auckland Theology & Religious Studies blog, the Yoda impersonator was quite possibly intended to represent the devil attired as a demonic doctor of canon law, signifying that some clerics charged to uphold the law were actually corrupt and exploitative of their flock. The only link, conversely, to Samson is a series of illustrations concerning his life that run along the bottom edge of certain folios of the Smithfield Decretals (including the folio containing the Yoda image in the main text), but which have no connection whatsoever with the subject of the main text.

A snail-cat, depicted in the Maastricht Hours – an illuminated devotional manuscript produced in the Netherlands during the early 1300s (public domain)

A snail-cat, depicted in the Maastricht Hours – an illuminated devotional manuscript produced in the Netherlands during the early 1300s (public domain)However, it is conceivable that this controversial figure may have no religious significance at all, but was merely inserted as a joke by one of the manuscript's illuminators. The creation of non-existent entities by illuminators as sly subversive humour or merely to relieve the tedium of the lengthy task at hand when copying or illustrating such manuscripts is well known, and has even resulted in the recurrent appearance of certain well-defined but entirely fictitious creatures, such as the snail-cat, for instance, as documented by me in a previous ShukerNature article (click here ).

Consequently, 'Yoda of the Smithfield Decretals' may well be nothing more than a medieval doodle, whose similarity to the Star Wars character is actually only a superficial one, but which has been blown out of all proportion by the shared monk attire. During the 9 months since Medieval Monsters was published, all manner of other explanations for the ostensible correspondence between the two figures have been aired online, ranging from the sober to the surreal. However, my personal favourite is one alleging that perhaps a time traveller viewed a Star Wars film featuring Yoda, then went back in time to the creation of the Smithfield Decretals and somehow succeeded in surreptitiously including a depiction of Yoda within its text.

As the late, great British broadcaster Robert Robinson was wont to say when faced with 'imaginative' answers to questions: "Ah, would that it were, would that it were".

The Yoda lookalike figure in situ on folio 30 verso from the Smithfield Decretals (British Library/public domain)

The Yoda lookalike figure in situ on folio 30 verso from the Smithfield Decretals (British Library/public domain)

Published on December 17, 2015 11:32

December 9, 2015

FROM MINI-REX TO MOON COW – UNRAVELLING THE RIDDLE OF AMERICA'S MODERN-DAY 'RIVER DINOSAURS'

Photograph allegedly depicting a shot mini-rex or 'river lizard' held by an unidentified figure - emailed by 'Derick' to Chad Arment in April 2000 (copyright owner unknown/identity and current location of 'Derick' unknown so could not be contacted; thus reproduced here for educational/review purposes only, on a strictly Fair Use basis)

Photograph allegedly depicting a shot mini-rex or 'river lizard' held by an unidentified figure - emailed by 'Derick' to Chad Arment in April 2000 (copyright owner unknown/identity and current location of 'Derick' unknown so could not be contacted; thus reproduced here for educational/review purposes only, on a strictly Fair Use basis)In January 2000, veteran American cryptozoologist Ron Schaffner was emailed by someone using only a generic, non-specific email and who identified himself simply as 'Derick', but whose information was anything but generic. Derick attracted Ron's interest straight away, thanks to his emailed report containing the following intriguing introductory statement:

I live in Pueblo, Colorado. I moved out here when I was six and since then I've heard stories of the prairie devil, the pig man and the mini-rex; there's even old Indian legends of evil river demons. You get older and you try not to believe in monsters, however not even the high school kids will have a kegger [outdoor keg beer-drinking teenage parties] down by the river without a raging fire and a lot of people [presumably to ensure that 'monsters' keep well away]. It's not like people don't see things, people see them they just don't make a big deal of it. If you live by the river like me you just get used to it.

Following that enticing preamble, Derick duly cut to the chase, describing his encounter with what appears to have been one of this region's mysterious 'mini-rexes'. He claimed that while he and a friend were riding the latter's dirt-bike close to the Fountain River near Pueblo one day in July 1998, they suddenly saw a truly extraordinary bipedal creature run across the clearing in front of them:

It was three to four feet long, greenish with black markings on its back, and a yellowish-orange under belly. It walked on its hind legs, never dragging its tail, its front limbs (I call them limbs because they were more like arms than anything) were smaller in comparison to the back ones and it had four or three claws/fingers. I'm not sure for it was seen at a great distance. It also had some kind of lump or horn over each eye. When it noticed our presence it let out a high pitched screech or some sort of bird chirping, that pierced my ears, and then took off.

Derick and his friend returned at once to Derick's house to fetch a camera, then returned to the location of their encounter and photographed the creature's three-toed, 2-in-diameter tracks (with a Marlboro Red cigarette placed alongside them in some photos for scale purposes). Derick also stated that he subsequently heard of other sightings, and discovered that a friend had actually photographed one such creature. Following some persuasion, the latter friend allowed Derick to send scans of those photos, together with his own track photos and July 1998 sighting account, to Ron, who in turn showed them to fellow American cryptozoologist Chad Arment, who has a particular interest in American mystery reptiles. However, as the photos showed little detail, even when magnified, Ron and Chad agreed that their subjects could easily be dinosaur models.

Nevertheless, Chad remained sufficiently intrigued to email Derick and state that if such beasts were indeed real, better evidence would be needed in order to confirm this. He didn't expect to receive a reply, but in April 2000 he did, in the form of an email enclosing two scans of the truly remarkable photograph opening this present ShukerNature blog article and also reproduced below:

Photograph allegedly depicting a shot mini-rex or 'river lizard' held by an unidentified figure - emailed by 'Derick' to Chad Arment in April 2000 (copyright owner unknown/identity and current location of 'Derick' unknown so could not be contacted; thus reproduced here for educational/review purposes only, on a strictly Fair Use basis)

Photograph allegedly depicting a shot mini-rex or 'river lizard' held by an unidentified figure - emailed by 'Derick' to Chad Arment in April 2000 (copyright owner unknown/identity and current location of 'Derick' unknown so could not be contacted; thus reproduced here for educational/review purposes only, on a strictly Fair Use basis)Referring to the creature in this photo as a 'river lizard' (but which is presumably the same type as the mini-rex that he saw), Derick stated that it had taken him some time to obtain scans of it, and that he didn't know when or specifically where it had been snapped, only "somewhere" in Colorado. As this creature does not resemble any species currently recognised by science, Chad later attempted to email Derick for further details, but received an automated reply that Derick's email address was no longer in operation, and has never heard from him again.

However, Chad has learnt from another source that the term 'river dinosaur' has apparently been used in relation to such creatures, and even that an individual who had previously collected Colorado reptiles for some of Chad's friends working in the pet trade had also offered to capture for them some 'river dinosaurs' (whose description compared closely to the appearance of the 'river lizard' in the above photo supplied by Derick). Unfortunately, Chad's friends had been forced to decline this exciting offer due to lack of funds.

The 'river lizard' photograph supplied by Derick has been floating around online for many years now, and has attracted much attention and numerous comments on the many websites where it has appeared, with the consensus seeming to be that it is a hoax, although this has never been confirmed. (I have conducted several Google-image searches, concentrating variously upon the whole image, the section featuring the person, the section featuring the creature, etc, but all to no avail.) However, it certainly contains some anomalous features, especially in relation to the creature's appearance, as commented upon by Chad in an account of this and other bipedal 'dinosaur' sightings reported from the U.S.A. (North American Biofortean Review, vol. 2, #2, 2000).

For example: if the 'river lizard' had only recently been shot when this photograph was snapped, and bearing in mind that recently-dead reptiles are normally very limp, and also bearing in mind that it was being held vertically, why is its tail curving inward rather than simply hanging straight down? And why is its mouth gaping open rather than being held closed, or at least nearly so, as one would expect under the above-listed conditions? As Chad also pointed out, very convincing life-like rubber models of dinosaurs can be readily obtained nowadays, so we cannot be sure that the 'river lizard' in the photo was ever a living entity anyway.

And even if it was once alive, thanks to the photo-manipulation software that was already available back in 2000 there is no certainty that this creature's appearance hasn't been profoundly modified digitally from whatever it was originally. Moreover, the entire photograph might conceivably be a cleverly-constructed melange, i.e. an original photo of a person holding a gun into which a second, digitally-manipulated photo of some animal has been deftly incorporated. Certainly, whenever I've looked at it, I've been struck by just how very odd, how very unnatural its image seems to be, and I don't just mean the bizarre appearance of the 'river lizard' itself but the whole image. Even the person's face is so obscured by the shadow of their hat that I'm not exactly certain whether they are male or female. But returning to the 'river lizard': having spent a lifetime observing animals in photos and in the living state, at the risk of being accused of sounding unscientific and overly reliant upon gut instinct it just doesn't look 'right' to me.