Karl Shuker's Blog, page 36

August 10, 2015

THE HYDRA OF LERNA – GETTING AHEAD (OR SEVERAL!) IN FICTION, FAKERY, AND FACT

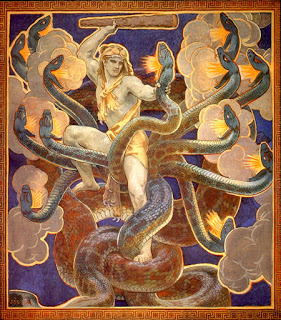

Exquisite depiction of Heracles battling the hydra by John Singer Sargent, 1921 (public domain)

Exquisite depiction of Heracles battling the hydra by John Singer Sargent, 1921 (public domain)Among the most unusual, and deadly, dragons, of classical mythology was the Lernaean hydra - whose slaying constituted one of the twelve great labours of the Greek hero Heracles (Hercules in Roman mythology).

Although this monster is usually depicted as wingless and only two-legged, thereby resembling the lindorm morphological category of dragon, it was more than ably compensated by virtue of its numerous heads (generally given as nine, but sometimes only seven, or as many as thirteen), each borne upon a separate neck. And each time that a head was cut off, two new ones grew in its stead, until Heracles successfully countered this by burning each neck as soon as its head was lopped off.

Yet despite this brave act putting an end to the hydra as a living entity, its name and fame have lived on, passing down throughout history, remaining vibrant and indescribably versatile even today - as will now be revealed.

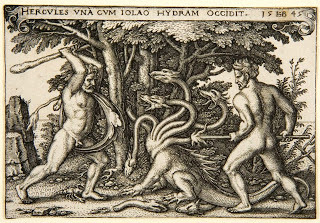

The hydra as portrayed in Conrad Gesner's famous bestiary Historiae Animalium(1558) (public domain)

The hydra as portrayed in Conrad Gesner's famous bestiary Historiae Animalium(1558) (public domain)HOW HERACLES DISPATCHED THIS MANY-HEADED DRAGON OF CLASSICAL MYTHOLOGY

The chimaera - a lion-headed monstrosity with a goat's head sprouting from its back, and a living serpent for a tail. The dragon Ladon - ferocious protector of the Hesperides' garden of the golden apples. Orthos, a fearful hound with two heads - and his even more hideous brother, the three-headed hell-hound, Cerberus. These were just a few of the gruesome monsters spawned in ancient Greece by the union of a terrifying hundred-headed giant called Typhon and his equally loathsome bride, the serpent-bodied Echidna - but none was more horrifying than the most terrible member of their vile brood, for that was the hydra.

Little wonder, then, that even the fearless hero Heracles was somewhat apprehensive as he stood outside the vast dank cave at Lerna that harboured this monstrous creature. As the second of his twelve great labours, he had been sent to this tormented district of Argolis, in southern Greece, by the cowardly king Eurystheus, who had commanded him to liberate Lerna by slaying the hydra - which was wilfully slaughtering its populace, and blighting with virulent vapour its countryside, transforming it into a gloomy wilderness of marshland.

French engraver Bernard Picart's dramatic depiction of Heracles clubbing the hydra (public domain)

French engraver Bernard Picart's dramatic depiction of Heracles clubbing the hydra (public domain)Assisted by his nephew Iolaus, who had faithfully accompanied him on this dangerous quest, Heracles lit a series of torches that they had fashioned from bundles of grass, and fired them into the hydra's grim lair in order to expel its foul occupant. Great clouds of evil-smelling smoke billowed out of the cave-mouth, and at the very heart of this choking mass of fumes something writhed, and roared. The two men backed away, coughing and wiping the acrid vapour from their streaming eyes - and when they looked back, they beheld a sight so dreadful that even the fiery blood of Heracles ran cold in his veins.

The smoke had dispelled, exposing an immense bloated mass of pulsating flesh, obscenely corpulent and of a sickening pallid hue. Superficially, it invited comparison with a grotesque octopus or squid, for above this obese, sac-like body thrashed a flailing mass of lengthy tentacle-like appendages - but that was where any such resemblance abruptly ended. For as Heracles and Iolaus could see only too clearly, these 'tentacles' were, in fact, long, powerful necks - and each of these necks, nine in total number, terminated in an evil horned head, the head of a dragon. This, then, was Heracles's grisly adversary - the Lernaean hydra.

Heracles and Iolaus dispatching the hydra with club and fire, depicted in 1545 by German engraver-painter Hans Sebald Beham (1500-1550) (public domain)

Heracles and Iolaus dispatching the hydra with club and fire, depicted in 1545 by German engraver-painter Hans Sebald Beham (1500-1550) (public domain)When its heads spied him, they emitted a deafening sibilation of hissing fury that whistled through his ears like a thousand shrieking ghosts, and each lunged forward, intent upon seizing this puny, vainglorious human in its bone-crunching jaws. Undaunted, Heracles raised his mighty club, and swung it down with terrible force, crushing into a shapeless mass the skull of the nearest of the nine - but to his horror, the head did not die. Instead, its flattened cranium promptly expanded, enlarged, and split into two - and each of the two halves immediately transformed into a new head. From the single original version, shattered by Heracles's club, two brand-new heads had instantly regenerated! Moreover, this deadly duplication occurred every time that he succeeded in destroying one of its heads.

Soon, the hydra would possess such a quantity of heads that it would certainly quash even the unrivalled monster-annihilating prowess of Greece's most exalted hero - unless he could devise a method of preventing them from replicating. Glancing at the smouldering sheaves of grass that he had used to drive out the beast from its cavernous retreat, however, Heracles suddenly saw an answer to his dilemma, and he quickly set Iolaus to work, preparing a new set of flaming torches.

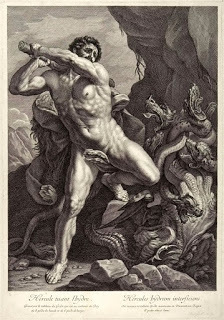

Heracles clubbing the ferocious hydra, depicted by the Baroque-Era French engraver Gilles Rousselet (1610-1686) (public domain)

Heracles clubbing the ferocious hydra, depicted by the Baroque-Era French engraver Gilles Rousselet (1610-1686) (public domain)Yet another of the hydra's heads swung down, jaws fully agape in a bid to grasp Heracles with its venomous fangs, and once again he crushed its skull with a single crunching blow of his bloodied club - but before it could begin to bifurcate into two new heads, Iolaus handed him a fiery brand, which he thrust into the gory pulp of the original smashed skull. The flames incinerated its flesh, which meant that it could no longer replicate - Heracles had discovered the secret of destroying the hydra!

From then on, the battle became increasingly one-sided - each head that attacked was swiftly destroyed with physical force and burning flame, until at last only a single head remained. This one, however, was immortal, immune to the scorching rapture of fire - but not to the merciless, decapitating thrust that it received from Heracles's razor-sharp sword.

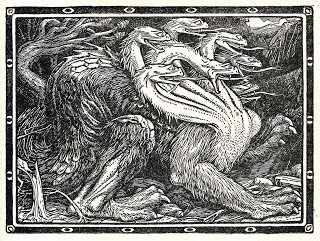

An uncommonly hirsute seven-headed dragon, as portrayed in this early 20th Century illustration by John D. Batten (public domain)

An uncommonly hirsute seven-headed dragon, as portrayed in this early 20th Century illustration by John D. Batten (public domain)The most terrible polycephalic dragon that the world had ever seen was no more, and never would be again - not even Typhon and Echidna could have spawned its hideous likeness a second time.

WAS THE MYTHICAL HYDRA INSPIRED BY MAINSTREAM CEPHALOPODS?

It is interesting to note that certain depictions of the Lernaean hydra on ancient Greek pottery were quite evidently inspired not by a reptilian dragon, but rather by either an octopus or a squid.

Heracles and the Hydra Water Jar (Etruscan, c. 525 BC) (© Getty Villa - Collection /Wikipedia)

Heracles and the Hydra Water Jar (Etruscan, c. 525 BC) (© Getty Villa - Collection /Wikipedia)Both of these multi-tentacled cephalopod molluscs are common in the seas off Greece and its islands, and it is easy to understand how, after seeing a captured specimen on land flailing its tentacles about its large bulbous body, the legend of a monster with numerous necks could have arisen.

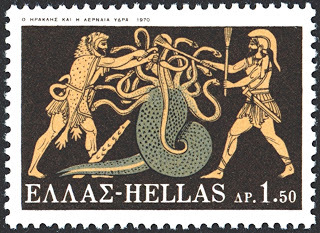

Depiction of Heracles battling an octopus-like hydra on ancient Greek pottery, as reproduced upon a Greek postage stamp from 1970 in my collection (© Greek postal service)

Depiction of Heracles battling an octopus-like hydra on ancient Greek pottery, as reproduced upon a Greek postage stamp from 1970 in my collection (© Greek postal service)In modern-day zoology, the hydra lives on at least in name if not in nature, courtesy of a group of small freshwater cnidarian polyps known as hydras. These can readily yield multi-headed forms if injury, or deliberate intent via laboratory experiments, divides their original single heads into two or more sections, each section duly regenerating into a complete head but remaining attached to the single body. Also, several buds can develop asexually from a single body, each with its own head; usually they then break off to become separate entities, but sometimes they remain attached to their progenitor polyp.

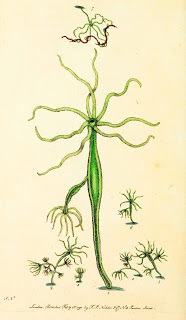

Vintage illustration from The Naturalist's Miscellany, vol. 1, 1789, depicting the green hydra Hydra viridis (public domain)

Vintage illustration from The Naturalist's Miscellany, vol. 1, 1789, depicting the green hydra Hydra viridis (public domain)LINNAEUS AND THE HOAXED HYDRA OF PRAGUE

Truly marvellous in its own deceiving manner was the hoaxed hydra that was removed from a church in Prague in 1648 and subsequently owned by Johann Anderson, the Burgomaster of Hamburg. So spectacular was this preserved wonder that Anderson even rejected an offer of 30,000 thalers for it from Frederick IV, king of Denmark. In basic form, the hydra resembled a standard lindorm, sporting a long tail and sturdy scaled body but only two limbs and no wings. Instead of just a single neck and head, however, it boasted no less than seven of each, with all of the necks emerging from a common base.

Yet despite the hydra's extraordinary appearance, its perceived monetary value eventually decreased, until by 1735 negotiations had begun for its sale at a mere 2000 thalers. Before these could be completed, however, eminent naturalist Carl Linné (who subsequently Latinised his name to Linnaeus) examined this celebrated specimen, and exposed it as a fraud. The heads, jaws, and feet were those of weasels, and a series of snake skins had been pasted all over its body.

Depiction of the hoaxed hydra of Hamburg in Albertus Seba's Cabinet of Natural Curiosities (Vol. 1), 1734 (public domain)

Depiction of the hoaxed hydra of Hamburg in Albertus Seba's Cabinet of Natural Curiosities (Vol. 1), 1734 (public domain)Linnaeus speculated, however, that this exhibit had probably been created not by wily vendors to sell as a supposedly genuine hydra to some unwary buyer for an eye-watering sum of money, but rather by monks as a representation of the seven-headed dragon of the Apocalypse with which to chastise and terrify disbelievers. Yet whatever the reason, the result was outstanding, but even so, once this hoaxed hydra's true nature had been revealed by Linnaeus, the deal for its sale fell through, and shortly afterwards the hydra itself vanished – never to be seen again.

Incidentally, the seven-headed dragon of the Apocalypse, bearing ten horns and seven crowns, was the guise assumed by the devil, who fought with his rebel angels against the valiant St Michael and the mighty hosts of Heaven, as narrated in the Bible's Book of The Revelation of St John the Divine. Ultimately, St Michael cast the dragon out, hurling him down to earth with his mutinous acolytes. It is illustrated in various of the tapestries constituting the medieval French Apocalypse Tapestry (Tapisserie de l'Apocalypse), which depicts the Apocalypse from the Revelation of St John. The oldest surviving French tapestry, it was commissioned by Louis I, the Duke of Anjou, and was produced between 1377 and 1382.

'The Beast From the Sea' ('La Bête de la Mer'), one of a series of tapestries constituting the medieval Apocalypse Tapestry (Tapisserie de l'Apocalypse); this one depicts the Dragon of the Apocalypse handing its sceptre of authority to the leopard-bodied Beast from the Sea, also seven-headed but with lion heads, not dragon heads (public domain)

'The Beast From the Sea' ('La Bête de la Mer'), one of a series of tapestries constituting the medieval Apocalypse Tapestry (Tapisserie de l'Apocalypse); this one depicts the Dragon of the Apocalypse handing its sceptre of authority to the leopard-bodied Beast from the Sea, also seven-headed but with lion heads, not dragon heads (public domain)THE HYDRA IN DREAMS, THE HEAVENS, HERALDRY, AND ART

Different types of dragon mean different things in dreams. A classical dragon with wings, for instance, can epitomise a transition, an ascent from a lower to a higher level of maturity. A many-headed hydra, conversely, signifies that the dreamer is plagued by a recurrent problem, one that he has tried to deal with several times but always unsuccessfully, so it is still appearing in his life, awaiting a satisfactory, conclusive resolution.

Heracles attacking and being attacked by the hydra as portrayed in this postage stamp issued by Monaco in 1981, from my collection (© Monaco postal services)

Heracles attacking and being attacked by the hydra as portrayed in this postage stamp issued by Monaco in 1981, from my collection (© Monaco postal services)Heracles's most formidable foe is represented in the night sky by a constellation, but no ordinary, insignificant one – nothing less than Hydra, the largest constellation of all, and one of the 48 constellations first recognised by Ptolemy. Yet despite its name, the distribution of its stars across the sky is such that Hydra the constellation bears much more of a resemblance in shape to a writhing single-headed serpent than to the polycephalic monster battled by Heracles. This in turn can cause a degree of confusion with another constellation, Hydrus, which is represented as a water snake. Moreover, Hydra itself is adapted from an ancient Babylonian serpent constellation.

Hydra constellation, in Urania's Mirror (public domain)

Hydra constellation, in Urania's Mirror (public domain)Heracles himself is also represented in the night sky by a constellation – Hercules (his Roman name). Fifth largest in the night sky and another of Ptolemy's 48 originals, this constellation, interestingly, is believed by some researchers to have originally been united by ancient Babylonian sky-watchers with Draco, yielding a serpent-bodied human.

The dragon is a very popular symbol in heraldry, and appears in many different forms. One of these is the hydra, but no ordinary one. As if this monstrous creature were not deadly enough already, a seven-headed hydra sporting a pair of wings appears in the crest of various French families, including Barret, Crespine, and Lownes.

The hydra being clubbed by Heracles in a painting by Antonio del Pollaiolo (public domain)

The hydra being clubbed by Heracles in a painting by Antonio del Pollaiolo (public domain)Popular subjects for Renaissance artwork were the twelve labours of Heracles, including the slaying of the Lernaean hydra. Having said that, it was a decidedly scrawny, unimpressive specimen that was clubbed senseless by the hero in the painting by Italian artist and sculptor Antonio del Pollaiolo (1432-1498). Equally unimposing (albeit feather-winged) was the individual confronted by Heracles in an oil painting on wood from 1555-56 by Italian painter Marco Marchetti of Faenza.

Hydra oil painting by Marco Marchetti of Faenza (public domain)

Hydra oil painting by Marco Marchetti of Faenza (public domain)Fortunately, however, more formidable depictions of this many-headed lindorm also exist, such as the robust portrayal by Spanish painter Francisco de Zurbarán (1598-1664), as well as various post-Renaissance examples, like the vibrant engraving by Bernard Picart (1673-1733), and a truly exquisite portrayal by American artist John Singer Sargent (1856-1925), which opens this present ShukerNature blog article.

Francisco de Zurbarán's dark, nightmarish portrayal of the battle between the hydra and Heracles, painted in 1654 (public domain)

Francisco de Zurbarán's dark, nightmarish portrayal of the battle between the hydra and Heracles, painted in 1654 (public domain)Nor could we – or should we – forget the huge, spectacular sculpture of Heracles confronting a truly terrifying hydra created by Danish Symbolist-allied sculptor Rudolph Tegner (1873-1950), installed in Elsinore, Denmark.

Rudolph Tegner's spectacular sculpture at Elsinore, Denmark (© Rudolph Tegner/Flickr)

Rudolph Tegner's spectacular sculpture at Elsinore, Denmark (© Rudolph Tegner/Flickr)Perhaps the strangest hydra portrait, however, is its depiction as a giant multi-limbed lobster-bodied monstrosity battling Heracles and Iolaus in an engraving dating from 1565.

The hydra portrayed as a weird composite of many-headed dragon and multi-limbed, carapace-bodied crustacean (public domain)

The hydra portrayed as a weird composite of many-headed dragon and multi-limbed, carapace-bodied crustacean (public domain)THE HYDRA IN THE MOVIES AND IN LITERATURE

The hydra has featured in a number of films, and also in various works of fiction.

In the classic stop-motion fantasy film 'Jason and the Argonauts' (1963), featuring the astonishing creations of Ray Harryhausen, the Golden Fleece sought by Jason and his men is guarded by the Colchis dragon. Although this is usually depicted as a winged classical dragon, for maximum visual appeal Harryhausen represented it in this film as a multi-headed hydra-like version instead. It kills one of Jason's men, the treacherous Acastus, before being slain by Jason himself, who is then able to steal the Golden Fleece, and later returns with it in triumph to Thessaly.

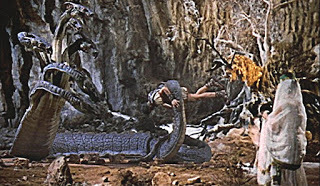

Ray Harryhausen's spectacular Colchis hydra in the 1963 British Columbia Pictures fantasy movie 'Jason and the Argonauts' (© Columbia Pictures)

Ray Harryhausen's spectacular Colchis hydra in the 1963 British Columbia Pictures fantasy movie 'Jason and the Argonauts' (© Columbia Pictures)In 1997, the Disney animated feature film 'Hercules' was released, and, as befitting a movie based (albeit loosely) upon tales from Greek mythology, it included an epic battle between the young demi-god hero and the Lernaean hydra. This multi-headed dragon has been summoned by Hades to destroy Hercules, but when he successfully kills it by causing a landslide, our hero finds himself elevated to celebrity status among the general public.

CineTel Films released a made-for-cable-television movie entitled 'Hydra' in 2009, subsequently making it available internationally on DVD. A slick blend of thriller, horror, action, and mythology, it tells the tale of how the legendary Lernaean hydra is reawakened from centuries of dormancy by a major seaquake near its volcanic Mediterranean island domain. The bloodthirsty many-headed monster, no doubt hungry after its prolonged fasting, proceeds to chomp up everyone who sets foot on its island, including a party of man-hunters, some of their ex-convict targets (one of whom is played by Hollywood and television actor George Stults), and even one of the film's two leading protagonists, a female archaeologist. The special effects breathing life into the hydra are as impressive as its rapacity for its human prey is unrelenting.

Poster from the 2009 CineTel Films movie 'Hydra' (© CineTel Films)

Poster from the 2009 CineTel Films movie 'Hydra' (© CineTel Films)William Beckford's initially anonymous Gothic novel Vathek, published in 1786 and telling the fall from power into eternal damnation of the Caliph Vathek of the Abassides, features a winged hydra called Ouranabad.

A Ballantine Books edition of Vathek(© Ballantine Books)

A Ballantine Books edition of Vathek(© Ballantine Books)Dragons of a traditional, ferocious nature appear in various volumes of the long-running series of children's fantasy novels entitled The Spiderwick Chronicles (2003-2004) and Beyond the Spiderwick Chronicles (2007-2009) by Tony DiTerlizzi and Holly Black. These include serpent dragons like the venomous worms reared by the evil ogre Mulgarath, and a huge many-headed hydra with gills known as the Wyrm King.

An acid-spitting hydra, whose life-force is linked to the ever-increasing appearance of Monster Donut shops, appears in Rick Riordan's teenagers' fantasy-adventure novel, The Sea of Monsters, the second in his bestselling Percy Jackson series, but it is slain by a cannon from a battleship.

The Wyrm King

– Book #3 in the Beyond the Spiderwick Chronicles series, published in 2009 (©Tony DiTerlizzi and Holly Black/Simon & Schuster)

The Wyrm King

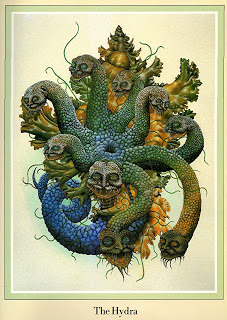

– Book #3 in the Beyond the Spiderwick Chronicles series, published in 2009 (©Tony DiTerlizzi and Holly Black/Simon & Schuster)Inventorum Natura: The Expedition Journal of Pliny the Elder (1979) is a spectacular tome compiled and exquisitely illustrated by fantasy writer-artist Una Woodruff. The premise behind this very skilfully-prepared volume is that it is a painstaking reconstruction of a supposedly long-lost work written in Latin by real-life Roman author-naturalist Pliny the Elder (23-79 AD), describing the astonishing fauna and flora that he allegedly observed during a purported three-year expedition to distant lands, an incomplete version of which Woodruff happened to rediscover. It includes several types of dragon – the pyrallis, basilisk, sea dragons, dragon-fishes, amphisbaena, Eastern dragons, Western dragons, and a British hydra.

Britain's very own hideous hydra, from Inventorum Natura (© Una Woodruff)

Britain's very own hideous hydra, from Inventorum Natura (© Una Woodruff)A UBIQUITY OF HYDRAS

Nor is this the extent of the hydra's popularity – indeed, even today it is virtually ubiquitous in the frequency and diversity of namesakes and commemorations. These include (but are by no means limited to): Hydra, the outermost known moon of the dwarf planet Pluto, discovered in June 2005; Hydra, an American professional wrestler; Hydra, one of the the Saronic Islands of Greece in the Aegean Sea, which I visited back in 1977 (though technically this is named after the water springs there rather than the monster); Hydra, a fictional secret terrorist organisation in the Marvel comics, and also a villain in Lee Falk's comic strip 'The Phantom'; Hydra, an American southern rock band; the Hydra Trophy, which is awarded to the winner of the roller derby WFTDA Championships; Hydra, a chess computer; 'HMS Hydra', the name of several different Royal Navy vessels; Hydra, an early computer software operating system, created in 1971 at Carnegie-Mellon University; Hydra 70, an air-to-ground rocket; Hydra, a monstrous opponent waiting to be faced in the role-playing video game 'Titan Quest', released worldwide by THQ in June 2006; 'Hydra', a song by American rock band Toto from their 1979 album 'Hydra'; Hydra, the professional name of Texas-born roller derby skater Jennifer Wilson; and The Hydra, a literary magazine once edited by WW1 war poet Wilfred Owen and including poems by fellow war poet Siegfried Sassoon.

The hydra as featured in the role-playing video game 'Titan Quest', released by THQ (public domain)

The hydra as featured in the role-playing video game 'Titan Quest', released by THQ (public domain)Its debut may have been countless centuries ago, but from Heracles to Percy Jackson as just two of its numerous assailants upon its lengthy journey through time and culture the hydra shows no sign of diminishing on the world stage, the endless fascination with its terrifying ability to regenerate and duplicate its head count undoubtedly ensuring its survival to scare and surprise us for a very long time to come.

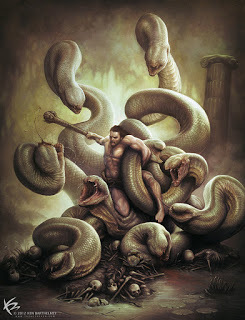

Heracles versus Hydra (© Ken Barthelmey/Deviantart.com - click here to view more of Ken's outstanding artwork in his deviantart gallery)

Heracles versus Hydra (© Ken Barthelmey/Deviantart.com - click here to view more of Ken's outstanding artwork in his deviantart gallery)This ShukerNature blog article is excerpted and expanded from my books Dragons: A Natural History and Dragons in Zoology, Cryptozoology, and Culture .

Published on August 10, 2015 15:06

August 6, 2015

EXPOSING THE CON IN ANACONDA - OR, HOW I MONSTERED A MONSTROUS SNAKE HOAX

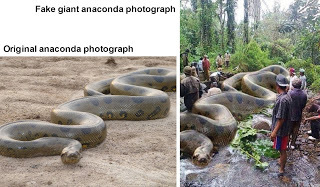

The online photo of a supposed gargantuan anaconda shot in Africa's Amazon River !! (photo-manipulated photograph's creator(s) unknown to me)

The online photo of a supposed gargantuan anaconda shot in Africa's Amazon River !! (photo-manipulated photograph's creator(s) unknown to me)Less than a month after debunking a trio of quasi-coloured mock pythons on ShukerNature (click here ), I was able to do the same to an even more outrageous hoax of the constrictor kind, this time involving a much-manipulated photograph of a green anaconda Eunectes murinus.

According to the record books, this anaconda species, the biggest known to science, rarely exceeds 20 ft long. However, many reports have been filed concerning a truly colossal form of anaconda supposedly existing amid the vast jungle swamplands and lagoons of Brazil and elsewhere in South America – the so-called sucuriju gigante – that allegedly far exceeds that size. In 1907, the subsequently-lost explorer Lieut.-Col. Percy Fawcett reputedly shot an estimated 62-ft specimen as it began to emerge from Brazil's Rio Abuna but couldn't salvage its monstrous form, and there have even been a few photographs made public that allegedly portray killed but never-preserved specimens of it (click here for my ShukerNature coverage of some examples). Could the subject of this present ShukerNature blog article be another such picture? I don't think so!

Photograph of a supposed 130-148-ft-long sucuriju gigante killed in or around 1932 at Manaos, Brazil, after having been captured alive (public domain)

Photograph of a supposed 130-148-ft-long sucuriju gigante killed in or around 1932 at Manaos, Brazil, after having been captured alive (public domain)During the late evening of 1 August 2015, I saw the startling photograph opening this ShukerNature article posted on Facebook friend Simon Hicks's 'Zen Yeti' FB group page. If it were genuine, the slain anaconda featured in it would be truly gargantuan – but was it genuine? The bizarre-looking, compressed coils of the snake didn't look natural, but any specimen that so dwarfed the humans standing around it (yet standing around it in a remarkably unconcerned, disinterested manner, I might add, for persons supposedly in such close proximity to so immense a snake, dead or otherwise) is always going to attract suspicion anyway.

It was linked to the timeline of one Rakesh Mintu Bjp, and when I clicked that link it took me to an annotated version of the photo on this person's timeline. I also checked online outside Facebook, and the photo and annotation had already appeared on many other websites during the past month or so. Consequently, neither had originated with Bjp – he had merely posted one such copy on his FB timeline, as had several other persons, I discovered, which means that the originator of the photo and annotation is currently unknown. Anyway, this is the annotation:

"World's biggest snake Anaconda found in Africa's Amazon river. It has killed 257 human beings and 2325 animals. It is 134 feet long and 2067 kgs. Africa's Royal British commandos took 37 days to get it killed."

Even if the photograph hadn't seemed dubious before (which it had!), after reading the garbled nonsense above I could now have no doubt whatsoever that it was a blatant, and exceedingly silly, hoax. And how did I know this? Where to begin?!!

Well, first and foremost: unless someone has sneaked it into Africa without telling me, the Amazon River is famous for being the largest in South America.

Secondly: unless someone had thoughtfully embedded a veritable 'kill-o-meter' inside the anaconda, how could anyone state so precisely how many humans and animals it had killed?

Thirdly: its length is more than 4 times the maximum confirmed length for any modern-day snake, and more than 3 times the maximum estimated length for the longest snake ever known from planet Earth – Titanoboa cerrejonensis, from the Palaeocene epoch in what is now Colombia, which is believed to have attained a maximum length of around 42 ft and a weight of around 2500 lb (1135 kg – only about half that of the photo's mega-anaconda).

Titanoboa

life-sized model exhibit of the Smithsonian Institution, in the Natural History Museum © Ryan Quick/Wikipedia – Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic License)

Titanoboa

life-sized model exhibit of the Smithsonian Institution, in the Natural History Museum © Ryan Quick/Wikipedia – Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic License)Fourthly: there is no such regiment as Africa's Royal British commandos.

And fifthly: how on earth could it take 37 days to kill this snake, huge though it would have been if real? A concerted artillery or machine-gun salvo to its head would surely have dispatched it in a far shorter time period.

Just after midnight on 2 August, I posted on my 'Journal of Cryptozoology' FB group's page a link (click here - but only accessible to members of my FB group) to the photo as it appeared on Rakesh Mintu Bjp's timeline.

All that was now needed was the original, non-manipulated anaconda photograph to bring this sorry snake saga to a well-deserved end, and, after spending all of 2 minutes online using Google Image after having posted the fake photo's link on my 'Journal of Cryptozoology' page, I duly uncovered it, here , on a page dealing with anacondas, from a Brazilian biology website entitled 'Bio Curiosidades'. If you scroll down the page, it is the fifth photo from the top of the page.

The original, non-manipulated anaconda photograph (©

www.ninha.bio.br

)

The original, non-manipulated anaconda photograph (©

www.ninha.bio.br

)The fake photograph had been produced by person(s) unknown simply by horizontally-flipping the above, original photograph to create a mirror-image version of it, then compressing it horizontally to yield those oddly-shaped coils, then either superimposing from a second photo the people and background around it, or, more probably, superimposing it upon a second photo containing the people and background.

After finding this photograph on the 'Bio Curiosidades' website, I duly posted on my 'Journal of Cryptozoology' FB group page a link to it, beneath my previous one linking to the fake photo. Case closed.

Thus endeth the tale of the giant anaconda that was merely a giant con.

The original, non-manipulated anaconda photograph alongside the fake, photo-manipulated version; NB - I have horizontally-flipped the original photo here in order to provide a direct comparison of it alongside the fake photo (© www.ninha.bio.br for original photo/creator(s) of fake photo unknown to me)

The original, non-manipulated anaconda photograph alongside the fake, photo-manipulated version; NB - I have horizontally-flipped the original photo here in order to provide a direct comparison of it alongside the fake photo (© www.ninha.bio.br for original photo/creator(s) of fake photo unknown to me)

Published on August 06, 2015 09:23

July 28, 2015

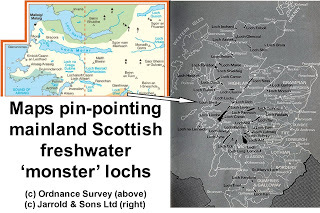

THE LONG-NECKED SEAL IN CRYPTOZOOLOGY - PART 2: FROM SWAN-NECKED AND HIDDEN-NECKED TO TIZHERUK AND NESSIE

Brian Froud's wonderful rendition of Peter Costello's proposed long-necked freshwater seal graces the cover of the 1975 Panther paperback edition of Costello's classic crypto-book In Search of Lake Monsters (© Peter Costello/Brian Froud/Panther Books)

Brian Froud's wonderful rendition of Peter Costello's proposed long-necked freshwater seal graces the cover of the 1975 Panther paperback edition of Costello's classic crypto-book In Search of Lake Monsters (© Peter Costello/Brian Froud/Panther Books)In Part 1 of this ShukerNature blog article (click here ), I investigated the candidature of an undiscovered species of giant long-necked seal as an identity for certain sea serpents, as promoted in particular by Drs Anthonie Oudemans and Bernard Heuvelmans. However, the concept of such a creature is not confined to the contemplation of marine cryptids, as now revealed.

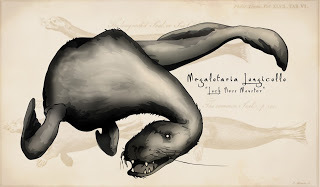

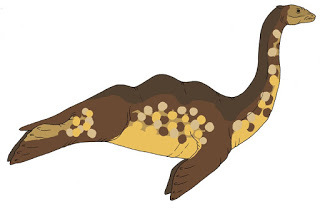

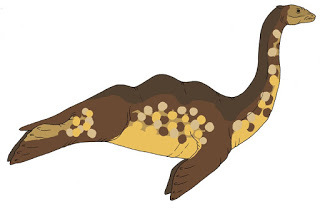

MEGALOTARIA , MEET NESSIE!

Heuvelmans believed that it was his hypothesised long-necked seal, which he had formulated and dubbed Megalotaria longicollis in his seminal book Le Grand Serpent-de-Mer (1965), rather than any postulated form of surviving plesiosaur that was responsible for those water monsters yielding the now-iconic, vertically-held, periscope-like head-and-neck image firmly planted in everyone's mind when picturing water monsters (and most especially the Loch Ness monster), whether marine or freshwater in habitat, though in his book he confined himself to those cryptids on record from the seas and oceans.

Just under a decade later, however, one of Heuvelmans's cryptozoological disciples and longstanding correspondents, Irish author Peter Costello, produced what was very much a companion book to his mentor's sea serpent tome but concentrating its attention instead upon lake monsters, in particular Nessie. (Judging from a footnote in his sea serpent tome – "Which will appear in a separate book on 'monsters' of lochs, lakes, marshes and rivers – freshwater unknown animals" – apparently Heuvelmans had originally planned to prepare such a book himself, but subsequently assisted Costello in producing his own book instead.)

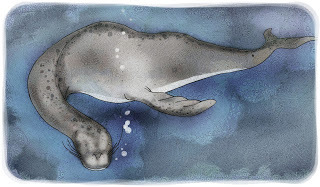

Nessie as a long-necked seal (© Robert Elsmore)

Nessie as a long-necked seal (© Robert Elsmore)Published in 1974, Costello's book was entitled In Search of Lake Monsters, and in this global study he followed much the same course as Heuvelmans did in his own, i.e. analysing an extensive collection of eyewitness reports of aquatic cryptids from around the world (but freshwater in this instance, with particular emphasis upon Scottish loch monsters), and then providing what he considered to be the most likely identification for them. Here, however, he diverged markedly from Heuvelmans, pursuing the Oudemans approach instead.

For whereas Heuvelmans had proffered a series of no less than nine different hypothetical cryptids as the collective solution to the sea serpent mystery, Costello bravely put forward only a single identity to explain virtually all of the lake monsters documented by him (including Nessie), diverse though they seemed to be in form, and therefore potentially inviting criticism of the kind that Oudemans's Megophias had attracted, i.e. that his solution was of the 'one-size-fits-all' variety – but that was not all. The single identity that he proposed was none other than Heuvelmans's very own giant long-necked seal, Megalotaria longicollis, thereby deeming it to be capable of living in freshwater habitats as well as in marine environments.

Artistic reconstruction of Megalotaria(Identity of artist/copyright holder unknown to me, so I would welcome receipt of appropriate credit details)

Artistic reconstruction of Megalotaria(Identity of artist/copyright holder unknown to me, so I would welcome receipt of appropriate credit details)As expected, therefore, for the most part Costello's description of this giant long-necked seal reiterated that of Heuvelmans for the same hypothetical species. However, he did also provide a few additional details, especially when specifically relevant to its inhabiting a freshwater domain, such as the assertion (rather than merely a speculation as offered by Heuvelmans for maritime Megalotaria) that it hunts by sonar, especially in stygian bodies of water like Loch Ness where vision is rendered largely or entirely superfluous, and that its hearing is therefore exceptionally sharp. As noted in Part 1 of this ShukerNature article, however, currently there is no conclusive evidence that pinnipeds do use sonar. He also claimed that it gives vent to a sharp staccato cry that sounds like a sea-lion's bark.

According to Costello, therefore, Nessie is merely a lake-dwelling long-necked seal, a freshwater-confined representative of Heuvelmans's marine Megalotaria, not even sufficiently distinct, despite its different habitat, to warrant any taxonomic delineation from the latter creature. Yet if this were true, why have other maritime pinnipeds only rarely or never established exclusively freshwater intraspecific populations? The only notable examples are two totally freshwater subspecies of the ringed seal Pusa(=Phoca) hispida – namely the greatly-endangered Saimaa seal P. h. saimensis (confined entirely to Finland's Lake Saimaa) and the Ladoga seal P. h. ladogensis (confined entirely to Russia's Lake Ladoga) – and some non-taxonomically discrete colonies of the common seal Phoca vitulinain a few lakes, such as Alaska's Lake Iliamna (already well-known to monster seekers for the giant fishes that allegedly inhabits its voluminous waters) and certain lakes in Quebec (a few researchers do elevate these Canadian individuals to the rank of a valid subspecies of common seal, known as the Ungava seal P. v. mellonae).

For the most part and with the vast majority of pinniped species (particularly the bigger ones), however, colonisation of freshwater simply does not occur. Yet it's not as if they never find their way inland from the sea – on the contrary, every year there are confirmed reports of seals in various rivers across the UK, for instance, and there are even verified records of specimens of known seal species in Loch Ness itself. However, whereas these have not led to the establishment of landlocked freshwater seal colonies (despite being much smaller than Megalotaria and therefore enabling a given volume and prey content of freshwater to accommodate and sustain more specimens of these seals than would be the case with a giant long-necked seal), according to the freshwater long-necked seal hypothesis the marine Megalotaria has somehow managed to accomplish this feat in numerous lakes all across the world.

Reconstructing Nessie as Megalotaria(© Robert Elsmore)

Reconstructing Nessie as Megalotaria(© Robert Elsmore)But how could this particular pinniped species (always assuming that it does exist, of course!) have been so markedly successful at freshwater colonisation on an international scale, which would surely have involved some very visible migrations into freshwater at the onset, while also being so extraordinarily (indeed, inexplicably) adept at eluding all attempts by scientists and laymen alike to confirm its reality that not so much as a single skull or skeleton has ever come to scientific attention anywhere across its entire global distribution?

It is just about within the realms of possibility that amid the vastness of the world's seas and oceans the maritime Megalotariacan still evade scientific detection even in modern times, but how can its freshwater counterparts do the same, even when their lakes occur in close proximity to human habitation? For me the concept of Megalotaria, whether in the seas or (especially) in freshwater lakes, remains a particularly thorny one both to grasp and to retain.

THE RAPACIOUS TIZHERUK AND REPTILIAN SEALS

Much less familiar a cryptid than the longneck sea serpent (and its freshwater equivalents) is a second aquatic mystery beast whose identity may be that of a still-undiscovered species of long-necked seal.

The Bering Seaseparates Alaska from Far East Russia, and contains a number of islands, which have been and, in some cases, still are inhabited by members of the Inuit nation. According to their traditional lore, the seas around at least two of these islands are home to a very mysterious, and allegedly highly dangerous, marine creature known as the tizheruk to the Inuits that once lived on tiny King Island (the entire population had resettled on the Alaskan mainland by 1970), and as the pal rai yuk to those still living on the much larger Nunivak Island.

In his book Searching For Hidden Animals(1980), pioneering American cryptozoologist Dr Roy P. Mackal (until his retirement working in an official capacity as a biochemist at the University of Chicago) noted that the Inuits originally inhabiting King Island had provided a detailed account of the greatly-feared tizheruk to ethnologist Dr John White, formerly of Chicago's Field Museum of Natural History. Based upon this information, which he shared with Mackal, White revealed that only the tizheruk's head and neck are usually observed, which rear 7-8 ft out of the water. The head is snake-like in appearance, and on the rare occasions when the tail is visible it can be seen to bear a flipper at its end. These animals are generally encountered in the bay areas, less frequently in the open sea, and by placing their ears against the inside of their boats the Inuits can hear them coming up for air. Moreover, if they tap against their boats, the sound often attracts these animals, their curiosity bringing them closer as they seek to discover the tapping noise's nature – not that the Inuits make a point of attracting tizheruks, however, because they claim that these creatures will actively attack humans, and they recounted numerous episodes to White in which hunters had reputedly been killed by them.

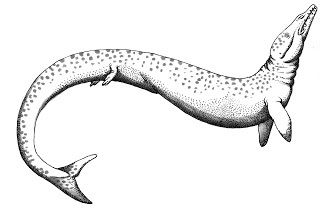

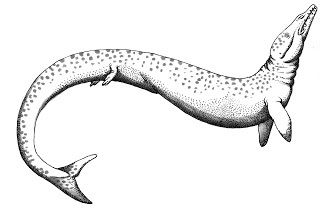

Artistic representation of the tizheruk (© Hodari Nundu)

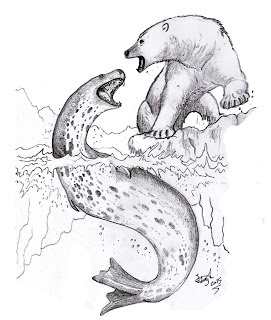

Artistic representation of the tizheruk (© Hodari Nundu)Mackal considered that the tizheruk was most probably a scientifically-unknown species of long-necked seal, and went on to suggest a more specific identity for it that is extremely thought-provoking. Namely, a currently-undiscovered northern counterpart of the Antarctic's (in)famously aggressive leopard seal Hydrurga leptonyx (aka the sea leopard).

Generally up to 12 ft long, weighing as much as 1300 lb, named after its throat's spotting, possessing a visibly elongate neck (especially when striking prey or stretching it to look at something – click here to view a very famous and truly spectacular example of its neck-elongating behaviour), and belonging to the phocid (earless) family of seals, this formidable beast is the second largest seal species indigenous to the Antarctic – only the southern elephant seal Mirounga leonina is bigger. It is also voraciously carnivorous, second only to the killer whale as the Antarctic's top predator, preying upon creatures as large as fur seals and emperor penguins.

A leopard seal stretching its neck to peer down into the sea, revealing how elongate it can become (© Jerzy Strzelecki/Wikipedia)

A leopard seal stretching its neck to peer down into the sea, revealing how elongate it can become (© Jerzy Strzelecki/Wikipedia)Moreover, those cryptozoologists favouring a reptilian rather than any mammalian identity for long-necked marine cryptids can take at least a crumb of comfort from the fact that, as commented upon by many scientists and laymen alike over the years, the leopard seal is startlingly reptilian in superficial appearance. This is especially true when seen on land, across which it can move at a remarkable speed by vertical wriggling.

In his book Sea Elephant: The Life and Death of the Elephant Seal (1952), British marine mammalogist L. Harrison Matthews penned the following memorable description of the leopard seal's very distinctive mode of terrestrial locomotion and its reptile-like mien while performing it, based upon his first-hand observation of this fascinating species at South Georgia:

And when it moves the resemblance [to a snake] is heightened for, unlike every other sort of seal, it holds the foreflippers closely pressed to the body and makes no use of them to help itself along – it wriggles with an up-and-down looping movement, pressing the chest and the pelvic region to the ground alternately.

Leopard seal wriggling via vertical undulations across some ice with its front flippers pressed tightly and almost invisibly against its body (public domain)

Leopard seal wriggling via vertical undulations across some ice with its front flippers pressed tightly and almost invisibly against its body (public domain)One of the best descriptions of this rapacious mammal's surprisingly reptilian appearance coupled with its notoriously savage nature can be found in Alfred Lansing's book Endurance: The True Story of Shackleton's Incredible Voyage to the Antarctic (1959). It documents the history of polar explorer Sir Ernest Shackleton's third and final Antarctic expedition, the ill-fated Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition 1914-17, during which his ship Endurance was lost, resulting in the expedition having to spend months camped upon an ice floe hunting seals and penguins in order to survive. Lansing's book includes an evocative account of a terrifying attack upon expedition member Thomas Orde-Lees one day in March 1916 by a ferocious, very tenacious, and extremely cunning leopard seal of exceptional size:

Returning from a hunting trip, Orde-Lees, travelling on skis across the rotting surface of the ice, had just about reached camp when an evil, knob like head burst out of the water just in front of him. He turned and fled, pushing as hard as he could with his ski poles and shouting for Wild to bring his rifle.

The animal – a sea leopard – sprang out of the water and came after him, bounding across the ice with the peculiar rocking-horse gait of a seal on land. The beast looked like a small dinosaur, with a long, serpentine neck.

After a half-dozen leaps, the sea leopard had almost caught up with Orde-Lees when it unaccountably wheeled and plunged again into the water. By then. Orde-Lees had nearly reached the opposite side of the floe; he was about to cross to safe ice when the sea leopard's head exploded out of the water directly ahead of him. The animal had tracked his shadow across the ice. It made a savage lunge for Orde-Lees with its mouth open, revealing an enormous array of saw like teeth. Orde-Lees' shouts for help rose to screams and he turned and raced away from his attacker.

The animal leaped out of the water again in pursuit just as Wild arrived with his rifle. The sea leopard spotted Wild, and turned to attack him. Wild dropped to one knee and fired again and again at the onrushing beast. It was less than 30 feet away when it finally dropped.

Two dog teams were required to bring the carcass into camp. It measured 12 feet long, and they estimated its weight at about 1,100 pounds…The sea leopard's jawbone, which measured nearly 9 inches across, was given to Orde-Lees as a souvenir of his encounter.

In his diary that night, [fellow expedition member Frank] Worsley observed: "A man on foot in soft, deep snow and unarmed would not have a chance against such an animal as they almost bound along with a rearing, undulating motion at least five miles an hour. They attack without provocation, looking on man as a penguin or seal" .

If, as postulated by Mackal, a creature comparable in form and ferocity to the leopard seal existed in the Bering Strait, it would certainly make a plausible identity for the tizheruk.

Leopard seal photographed on land in 1910 during the Terra Nova (British Antarctic) Expedition 1910-1912 (public domain)

Leopard seal photographed on land in 1910 during the Terra Nova (British Antarctic) Expedition 1910-1912 (public domain)Moreover, it is well known that leopard seals are very inquisitive. Quoting Matthews again from his elephant seal book:

Many a time when I have been fishing with the pram moored to the floating kelp I have brought a leopard [seal] right alongside by playing on its curiosity – if you tap gently and regularly with a rowlock on the gunwale or thwart you very soon find any leopard that may be near swimming alongside and looking up into your face.

Needless to say, this instantly recalls the identical activity carried out by the Inuits and the identical response to it given by the tizheruk.

Concluding his book's tizheruk coverage, Mackal speculated that this cryptid may resemble an enlarged version of the leopard seal in general appearance, but more specialised in that it either lacks forelimbs completely (as the Inuits seem not to mention them in their lore relating to it), or possesses reduced versions that it keeps folded tightly against its body when seen out of the water (just as the leopard seal does), rendering them virtually invisible and thus enhancing its superficially serpentine appearance.

Most southern hemisphere seals have a northern hemisphere counterpart of sorts, thereby making the leopard seal a noteworthy exception – unless its northern hemisphere counterpart is simply awaiting formal discovery, meanwhile living in scientific anonymity amid the chilling waters around certain islands in the Bering Sea?

SWAN-NECKED SEALS IN PINNIPED PREHISTORY

As noted at the beginning of Part 1 of this ShukerNature blog article, whereas plesiosaurs do at least have a fossil record substantiating their erstwhile existence, there is no evidence whatsoever in the currently-known fossil record for the existence at any time in pinniped history of an extreme, veritable giraffe-necked form like Megalotaria as predicted by Heuvelmans et al. as the identity of aquatic longnecks. Indeed, the only confirmed evidence for the former existence of anyseals possessing necks that were in any way longer than those of modern-day species is the series of fossil remains from the so-called swan-necked seals belonging to the extinct phocid genus Acrophoca.

Acrophoca longirostris

skeleton at the Smithsonian Institution of Natural History (© Ryan Somma/Wikipedia)

Acrophoca longirostris

skeleton at the Smithsonian Institution of Natural History (© Ryan Somma/Wikipedia)But just how long were their necks, and were they long enough to justify their popular 'swan-necked' tag? Dating from the late Miocene to early Pliocene (approximately 7-4 million years ago), the first species to be discovered and named was Acrophoca longirostris, which was formally described by palaeontologist Dr Christian de Muizon in 1981, and whose fossils have been uncovered in Chile and Peru. It measured up to 5 ft in total length, and in Muizon's description he revealed that both the length of its cervical vertebrae and the total length of its cervical column exceeded those of all modern-day seals. Moreover, its cervical column length was approximately 21% of its total vertebral column length, whereas in modern-day seals it is generally 17-19%. Its skull was also noticeably lengthy (hence its species name, longirostris).

Yet although the neck of A. longirostris was proportionately longer, it was not as streamlined as the neck of what may well be its closest modern-day relative – the leopard seal. Moreover, its flippers were less well-developed, a second characteristic indicating that it was less adapted for swimming than the leopard seal, and that it may therefore have spent much of its time around the Pacific's coasts rather than out at sea (a behavioural preference that, if true, has been perpetuated by the leopard seal, in spite of its more specialised form for swimming).

Acrophoca longirostris

depicted in a mural at the Staatliches Museum für Naturkunde Karlsruhe in Germany (© Markus Bühler)

Acrophoca longirostris

depicted in a mural at the Staatliches Museum für Naturkunde Karlsruhe in Germany (© Markus Bühler)As for its 'swan-necked' appellation: in a Tetrapod Zoology blog article of 4 February 2006 dealing with Acrophoca, palaeontologist Dr Darren Naish stated that because the necks of seals are sufficiently flexible to exhibit a marked lengthening effect when they lunge at prey, stretch, or spy-hop:

…when alive, Acrophoca would have been capable of looking even longer in the neck than we might think just from its fossils. But clearly it’s a stretch [pun intended?!] to imagine this animal as having a long long long neck like a swan, or a plesiosaur, so, sadly, ‘swan-necked seal’ really is a bit of an exaggeration.

In 2002, with fellow palaeontologist Dr Stig A. Walsh, Naish co-described what appeared to be a new, second Acrophoca species, based upon fossils retrieved in Chile, but they declined to give it a formal scientific name. This was because substantial new fossil material hailing from Peru suggested the presence of several additional Acrophocaspecies, so it was felt best to await their full description first. Interestingly, one of these new species had an even longer skull than A. longirostris, so it may have looked more unusual than the latter.

HIDDEN-NECK LONG-NECKED SEALS – A LITTLE-KNOWN PARADOX

Ironically, however, we do not even have to look back into prehistory to uncover bona fide, fully-verified long-necked seals. So far, this two-part article has been assessing attempts by various cryptozoologists down through the ages to propose as the identity of longneck aquatic cryptids the existence of a highly-specialised species of seal whose defining characteristic is its long neck. In reality, however, what is not readily realised is that science has already confirmed the existence of several such species – species, moreover, which are actually alive today. But how can this be? Allow me to explain.

With the notable exception of the leopard seal's well-delineated neck, in most modern-day seal species the neck is largely hidden, often concealed by blubber, to the point of seeming to be all but non-existent in certain forms. A close examination of such species' skeletons, conversely, reveals a very different – and extremely surprising – picture.

On 15 March 2013, American biologist Cameron A. McCormick's blog Biological Marginalia posted a fascinating article entitled 'The hidden necks of seals', containing a table of measurements obtained from a range of different pinniped species. For each species, the length of its neck was given as a percentage of the combined length of its thoracic and lumbar (T-L) vertebrae, and the results were quite remarkable to read. Using this comparison, the bearded seal Erignathus barbatus had the shortest neck among phocids, at only 21% T-L, whereas the harp seal Pagophilus groenlandicus boasted the longest neck, at 35% T-L – exceeding even the leopard seal's 29% T-L. As for otariids, the shortest neck was that of the Australian sea-lion Neophoca cinerea at 34.5% T-L, and the longest was that of the northern fur seal Callorhinus ursinus at 41% T-L.

An adult bull specimen of the northern fur seal (public domain)

An adult bull specimen of the northern fur seal (public domain)But what was most significant was that even the shortest necks were actually much longer than they outwardly appeared to be in the living animal. So in a very real sense, some already-known, modern-day seal species are actually cryptic long-necked seals, or, to be precise, hidden-neck long-necked seals.

In view of this unexpected revelation, one can scarcely even begin to guess at what the neck percentage T-L value might be for a giraffe-necked, Megalotaria-type of long-necked seal – especially when we take into account (judging at least from the above data) that there may be an additional neck portion hidden from sight beneath blubber at its basal region. In fact, such an exceptionally long neck could well be of truly plesiosaurian proportions!

THE SEAL(S) OF APPROVAL

Prior to the establishment of the Journal of Cryptozoology in 2012, the appearance in a peer-reviewed academic journal of a paper dealing with cryptids was probably just as rare as the beasts documented in it. This is why, back in late 2008 (and in June 2009 online), the publication by the mainstream scientific journal Historical Biology of a paper contemplating the possible existence of still-undiscovered pinniped species was of particular note – and, one hopes, an indication of increasing mainstream approval for serious cryptozoological research.

Authored by Drs Darren Naish and Michael A. Woodley (the latter being a Royal Holloway, University of London postgraduate biology student at that time), both with well known cryptozoological interests, together with Royal Holloway computer scientist Dr Hugh P. Shanahan, it was entitled ‘How many extant pinniped species remain to be described?’. In it, the authors examined the description record of the pinnipeds using non-linear and logistic regression models in an attempt to ascertain the number of still-undescribed species, and they combined that work with an evaluation of cryptozoological data, featuring such alleged pinniped cryptids as the longneck sea serpent, the merhorse, Vancouver’s serpentiform Cadborosaurus, and the tizheruk.

Artistic representation of Cadborosaurus as an exceedingly serpentiform pinniped-like cryptid (© Richard Svensson)

Artistic representation of Cadborosaurus as an exceedingly serpentiform pinniped-like cryptid (© Richard Svensson)From the results obtained, they revealed that three possibly new, currently undescribed species of pinniped match their statistical expectations, but even these, the authors felt, would need to possess some exceptional characteristics if they do indeed exist.

A giraffe-proportioned neck combined with huge body size would certainly be exceptional, but for all the reasons presented and assessed in this two-part article, it seems to me at least that these would be highly improbable characteristics for a seal species to possess and yet remain undiscovered by science, especially if it did indeed occur in both marine and freshwater habitats. Consequently, I am not expecting to witness the formal scientific discovery of a Megalotaria-type pinniped any day soon – but how I would love to be proved wrong!

AND FINALLY – THE ONE THAT WON'T GO AWAY

As readers of this article will no doubt have realised by now, I am definitely not a proponent of the giraffe-necked, Megalotaria-type giant seal as an identity for any aquatic cryptid. Consequently, I would like nothing more than to jettison it as far away from my thoughts as possible when reviewing such creatures, but there is one tantalising case that always prevents me from doing so – and this is it.

The Orkney Islandsand Caithness on the mainland of northern Scotland are separated by a strait of seawater known as the Pentland Firth, which is a popular habitat for seals throughout the year. Two species are known to occur here, the common seal and the grey seal Halichoerus grypus – but at about 9.30 am on or around 5 August 1919, off the Orkney island of Hoy, what seems to have been a third, and dramatically different, seal species also made an appearance in this strait, to the astonishment of its eyewitnesses. These consisted of a holidaying lawyer named J. Mackintosh Bell and some local cod fishermen friends of his whom he had chosen to work with on their boat while visiting the Orkneys. His friends had seen the creature before, were very perplexed as to what it might be, and had actually just begun to tell him about it in the hope that he may be able to identify what it was when the subject of their conversation abruptly appeared, not far away from the boat that they were in.

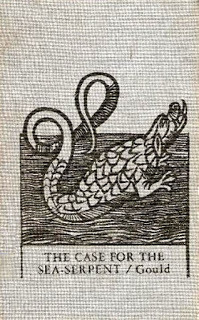

Lieutenant-Commander Rupert T. Gould of Britain's Royal Navy investigated and documented aquatic monsters in his spare time, and after learning about this sighting he contacted Bell and asked him for full details. Bell duly forwarded an in-depth account, which Gould later published in slightly abbreviated form within his book The Case For the Sea-Serpent (1930). Four years later, moreover, Gould wrote the first comprehensive study of Nessie, entitled The Loch Ness Monster and Others, spending several days at the loch, travelling around it on his motorbike, and interviewing many eyewitnesses during his researches for this book.

The Case For the Sea-Serpent

, Singing Tree Press's 1969 reprint (© Singing Tree Press)

The Case For the Sea-Serpent

, Singing Tree Press's 1969 reprint (© Singing Tree Press)As far as I am aware, Bell's original, full-length account has never appeared in print, but here is the slightly abbreviated version of it that Gould published in his sea serpent book:

The very first day I was there, I think it was about 5 August, I went afloat with a crew of four at about 9.30 a.m. for the purpose of firstly lifting lobster creels and then for cod fishing. On making our way to the creels, which had been set in a line between Brims Ness and Tor Ness, my friends said "We wonder if we will see that sea monster which we often see, and perhaps you will be able to tell us what it is."

We got to the creels, hauled some, and were moving slowly with the motor to another, when my friends said very quietly "There he is."

I looked, and sure enough about 25—30 yards from the boat a long neck as thick as an elephant's fore leg, all rough-looking like an elephant's hide, was sticking up. On top of this was the head which was much smaller in proportion, but of same colour. The head was like that of a dog, coming sharp to the nose. The eye was black and small, and the whiskers were black. The neck, I should say, stuck about 5-6 ft., possibly more, out of the water.

The animal was very shy, and kept pushing its head up then pulling it down, but never going quite out of sight. The body I could not then see. Then it disappeared, and I said "If it comes again I'll take a snapshot of it." Sure enough it did come and I took as I thought a snap of it, but on looking at the camera shutter, I found it had not closed owing to its being swollen, so I did not get a photo. I then said "I'll shoot it" (with my .303 rifle) but the skipper would not hear of it in case I wounded it, and it might attack us.

It disappeared, and as was its custom swam close alongside the boat about 10 feet down. We all saw it plainly, my friends remarking that they had seen it many times swimming just the same way after it had shown itself on the surface. My friends told me that they had seen it the year before just about the same place. It was a common occurrence, so they said. 'That year (1919) was the last of several years in which they saw it annually. It did not show itself again for two or three years, and then it was only seen once. As to its body, it was, seen below the water, dark brown, getting slightly lighter as it got to the outer edge, then at the edge appeared to be almost grey. It had two paddles or fins on its sides and two at its stern. My friends thought it would weigh 2 or 3 tons, some thinking 4 to 6. Not only my friends, but others, lobster fishing, got many chances of seeing it. . .

I may say that since 1919 all cod and other deep-sea coarse fish have left the Pentland Firth. I think the reason is that such monsters frequent the rocky caves, which are always covered by deep water. My friends think the animal may have been killed by a passing steamer, but I think it is possibly a native of warmer seas, and that if we get a really hot summer it will be seen again.

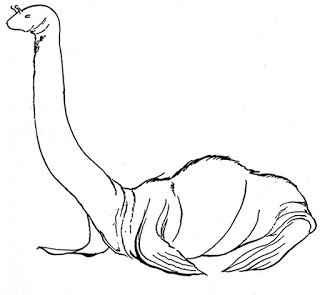

Bell also furnished Gould with two sketches that he had drawn of the animal, one showing how it looked when swimming underwater, plus a map of the approximate location where they had seen it. This was on the northern side of the Pentland Firth, roughly 1.6 miles north-westward of Tor Ness, the southern point of the Orkney island of Hoy, and about an eighth of a mile offshore, in some 20 fathoms of water.

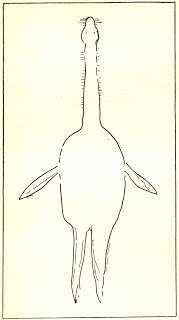

Bell's sketch of the creature that showed its head and very long neck (public domain)

Bell's sketch of the creature that showed its head and very long neck (public domain)When Gould wrote to Bell requesting the approximate dimensions of the creature, Bell provided the following additional details:

. . . Dimensions. Neck, so far as seen, say 6—7 feet. Body never seen when neck straight up, but just covered by the water. You could detect the paddles causing the water to ripple. When under water, swimming, the body, I think, to the end of the tail flappers would be about 12 ft. long - and, if the neck were stretched to say 8ft., the neck and body 18—20 ft. long. The skipper of the boat remarked that sometimes the top of the head, when seen from a boat vertically, was a bright red. Neck thickness say 1 foot diameter : Head very like a black retriever — say 6" long by 4" broad. Whiskers black and short. Circumference of body say 10-11 feet, but this I am not sure of, as I never saw all round it, but it would be 4-5 ft. across the back. . .

Needless to say, everything about this creature, both in Bell's verbal accounts and in his sketches, screams out "Seal!!" – very long neck notwithstanding.

Bell's sketch of the creature that showed its appearance when swimming underwater (public domain)

Bell's sketch of the creature that showed its appearance when swimming underwater (public domain)When documenting it in his 2007 review of the long-necked seal concept, Robert Cornes stated: "If this account is true and there appears no reason to think otherwise, then it is arguably the most convincing for the existence of a seal with a long neck". Indeed it is, because if Bell's testimony and sketches are accurate, it is difficult to comprehend how the creature that he and his friends saw could have been anything other than a seal – and an exceptionally, extraordinarily long-necked one at that.

It is for this reason, if for no other, that the concept of the long-necked seal, even in its most bizarre, giraffe-necked manifestation, continues to frustrate and fascinate me in equal measure, and seems destined to do so for a long time to come.

A delightful cartoon seeing the funny side of the long-necked seal, in every sense! (© William Rebsamen)

A delightful cartoon seeing the funny side of the long-necked seal, in every sense! (© William Rebsamen)This ShukerNature blog article is excerpted from my forthcoming book, Here's Nessie!: A Monstrous Compendium from Loch Ness .

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

CHAMPAGNE, Bruce A. (2007). A classification system for large, unidentified marine animals based on the examinations of reported observations. In: HEINSELMAN, Craig (Ed.), Elementum Bestia: Being an Examination of Unknown Animals of the Air, Earth, Fire and Water. Crypto (Peterborough), pp. 144-172.

COLEMAN, Loren and HUYGHE, Patrick (2003). The Field Guide to Lake Monsters, Sea Serpents, and Other Mystery Denizens of the Deep. Tarcher/Penguin (New York).

CORNES, Robert (2007). The seal serpent: the case for the surreal seal. In: DOWNES, Jonathan (Ed.), CFZ 2007 Yearbook(CFZ Press: Bideford), pp. 83-199.

COSTELLO, Peter (1974). In Search of Lake Monsters. Garnstone Press (London).

GOULD, R[upert].T. (1930). The Case For the Sea=Serpent. Philip Allan (London).

GREW, Nehemiah (1681). Musaeum Regalis Societatis: Or a Catalogue and Description of the Natural and Artificial Rarities Belonging to the Royal Society and Preserved at Gresham Colledge [sic]. W. Rawlins (London).

HEUVELMANS, Bernard (1965). Le Grand Serpent-de-Mer.Plon (Paris).

HEUVELMANS, Bernard (1968). In the Wake of the Sea-Serpents. Rupert Hart-Davis (London).

LANSING, Alfred (1959). Endurance: The True Story of Shackleton's Incredible Voyage to the Antarctic. Hodder and Stoughton (London).

MACKAL, Roy P. (1980). Searching For Hidden Animals: An Inquiry Into Zoological Mysteries. Doubleday (Garden City).

MAGIN, Ulrich (1996). St George without a dragon: Bernard Heuvelmans and the sea serpent. Fortean Studies, 3: 223-234.

MARDIS, Scott (1996). Sealing Champ's fate: more thoughts on the lake monster. Vox, 2 (No. 25; 7 August).

MATTHEWS, L. Harrison (1952). Sea Elephant: The Life and Death of the Elephant Seal. MacGibbon and Kee (London).

McCORMICK, Cameron A. (2013). The hidden necks of seals. Biological Marginalia, https://biologicalmarginalia.wordpres... 15 March.

MUIZON, Christian de (1981). Les vertébrés fossiles de la formation Pisco (Pérou). Première partie: deux nouveaux Monachinae (Phocidae, Mammalia) du Pliocene de Sud-Sacaco. Travaux de l’Insitut Français d’Études Andines, 22: 1-161.

NAISH, Darren (2001). Sea serpents, seals and coelacanths: an attempt at a holistic approach to the identity of large aquatic cryptids. Fortean Studies, 7: 75-94.

NAISH, Darren (2006). Swan-necked seals. Tetrapod Zoology, http://darrennaish.blogspot.co.uk/200... 4 February.

OUDEMANS, Anthonie C. (1892). The Great Sea-Serpent: An Historical and Critical Treatise. E.J. Brill (Leiden).

PARSONS, James (1751). A dissertation upon the class of the Phocae Marinae. Philosophical Transactions, 47: 109-122.

SHUKER, Karl P.N. (1995). In Search of Prehistoric Survivors. Blandford (London).

TAYLOR, Michael P.; WEDEL, Mathew J.; and NAISH, Darren (2009). Head and neck posture in sauropod dinosaurs inferred from extant animals. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica, 54(2): 213-220.

WALSH, Stig A. and NAISH, Darren (2002). Fossil seals from late Neogene deposits in South America: a new pinniped (Carnivora, Mammalia) assemblage from Chile. Palaeontology, 45: 821-842.

WOODLEY, Michael A. (2008). In the Wake of Bernard Heuvelmans. CFZ Press (Bideford).

WOODLEY, Michael A; NAISH, Darren; and SHANAHAN, Hugh P. (2008). How many extant pinniped species remain to be described? Historical Biology, 20(4): 225-235.

* * * * *

Published on July 28, 2015 17:29

July 27, 2015

THE LONG-NECKED SEAL IN CRYPTOZOOLOGY - PART 1: GIRAFFE SEALS AND SEA SERPENTS

Restoration of the Loch Ness monster as a long-necked seal (© Anthony Wallis)

Restoration of the Loch Ness monster as a long-necked seal (© Anthony Wallis)Although many mainstream palaeontologists may shudder at the merest thought of it, the Loch Ness monster's most readily-conceived public image will always be that of a typical plesiosaur – all neck, tail, and paddled limbs. Lurking in its shadow, never too far from scientific consciousness but a million miles away from popular recognition, however, is a second cervically-endowed yet very different identity candidate – the long-necked seal. Yet whereas the plesiosaur's at least erstwhile reality is unequivocally validated by the fossil record (albeit one in which this reptilian lineage is currently curtailed at a point over 60 million years ago), tangible evidence for the existence at any point in our planet's history of the kind of veritable giraffe-necked pinniped required to satisfy a mammalian identity for Nessie and other comparable 'periscope-profile' aquatic cryptids is conspicuous only by its absence. Indeed, to all intent and purpose there is no more proof for the reality of the long-necked seal than there is for the Loch Ness monster itself. So. when and how did this hypothetical horror come into theoretical being, and why does it persist in casting its nebulous shadow over the much more romantic (if no more realistic?) image of its plesiosaurian rival? It's time to find out!

A LONG-FORGOTTEN LONG-NECKED SEAL AT THE ROYAL SOCIETY

Although in modern times the concept of the long-necked seal as a zoological reality has been promoted most visibly by the cryptozoological triumvirate of Oudemans, Heuvelmans, and Costello, a mysterious creature not only fitting its description but actually referred to by that very same name had been documented as far back as the 1600s, but was completely overlooked by cryptid chroniclers until the 1990s. This was when American cryptozoologist Scott Mardis made a highly significant discovery, by spotting its long-forgotten description on microfiche at the University of Vermont, after which he duly brought this surprising but potentially very important beast to present-day public attention at long last via an article published on 7 August 1996 in a Vermont weekly magazine entitled Vox.

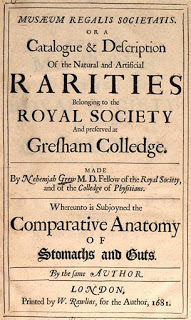

Scott's Vox article - click it to enlarge for reading purposes (© Scott Mardis/Vox)

Scott's Vox article - click it to enlarge for reading purposes (© Scott Mardis/Vox)In 1681, botanist Dr Nehemiah Grew published a catalogue of curiosities that could be found at that time in the museum of London's Royal Society. It was entitled Musaeum Regalis Societatis: Or a Catalogue and Description of the Natural and Artificial Rarities Belonging to the Royal Society and Preserved at Gresham Colledge [sic], and among the many specimen descriptions penned by Grew that it contained was one of a still-unidentified form of long-necked seal, based upon a preserved skin from an apparently young individual of this mystifying creature. Specifically referring to it as 'the long-necked seal', Grew described it on p. 95 of his catalogue as follows:

THE LONG-NECK'D SEAL. I find him no where distinctly mention'd. He is much slenderer than either of the former [two other pinnipeds documented by him earlier – see below]. But that wherein he principally differs, is the length of his Neck. For from his Nose-end to his fore-Feet, and from thence to his Tail, are the same measure. As also in that instead of fore-Feet, he hath rather Finns [sic]; not having any Claws thereon, as have the other kinds.

Conversely, in most known species of pinniped the length of their neck is only about half the length of their lower body.

Title page of Dr Nehemiah Grew's Musaeum Regalis Societatis (public domain)

Title page of Dr Nehemiah Grew's Musaeum Regalis Societatis (public domain)Grew's description was subsequently reiterated by James Parsons in a paper on marine seals published by Philosophical Transactions, a Royal Society journal, on 1 January 1751. In it, he listed various known species, and he included the long-necked seal within this list. Here is Parsons's slightly expanded version of Grew's original description of it:

He is much slenderer than either of the former; but that, wherein he principally differs, is the length of his neck; for from his nose-end to his fore-feet, and from thence to his tail, are the same measure; as also in that, instead of his fore-feet, he hath rather fins; not having any claws thereon, as have the other kinds. The head and neck of this species are exactly like those of an otter…That before described [the long-necked seal], was 7 feet and an half in length; and, being very young, had scarce any teeth at all.

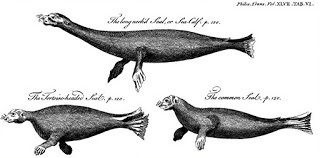

Accompanying its description, moreover, was an illustration of this unidentified creature (reproduced in Scott's Vox article), which portrayed it with a decidedly elongate neck, and was captioned 'the long necked seal or sea-calf'. It was depicted alongside two other seals (the same two as described by Grew prior to the long-necked seal).

Depiction of the Royal Society's long-necked seal specimen in Parsons's 1751 paper (public domain)

Depiction of the Royal Society's long-necked seal specimen in Parsons's 1751 paper (public domain)One of these two was termed 'the common seal' (i.e. Phoca vitulina), and was readily identifiable as this species. The other one, conversely, was more perplexing, being dubbed 'the tortoise-headed seal' (and which must wait for its own review elsewhere!). In his seal listing at the end of his paper, Parsons noted that the long-necked seal could be found "on the shores of divers[e] countries".

Be that as it may, no additional skins of long-necked seals have been forthcoming since the time of Grew and Parsons – their specimen thus being unique. So where is this zoologically-priceless skin today – what may well be the only physical evidence of a cryptozoological long-necked seal ever obtained by science? Tragically, no-one knows – like so many other remarkable specimens of mysterious, unidentified creatures, it has seemingly been lost, vanished into that great void where cryptid material seems irresistibly and inexorably drawn, never to be seen again.

FROM OUDEMANS TO HEUVELMANS – AND FROM MEGOPHIAS TO MEGALOTARIA

Although, therefore, as revealed above, this was not its earliest appearance in the historical chronicles, the long-necked seal first made cryptozoological headlines during the early 1890s. This was when Dutch zoologist and passionate sea serpent investigator Dr Anthonie C. Oudemans envisaged just such a beast as the answer to one of the greatest riddles in 19th-Century natural history – the elusive identity of the even more elusive 'great sea serpent'.

After analysing numerous sea serpent reports originating from seas all around the world and dating back centuries in some cases, Oudemans considered that their most plausible explanation was the scientifically-undiscovered presence of an enormous species of seal, boasting a cosmopolitan distribution, and morphologically distinguished from all presently-known species not only by its huge size (capable of growing up to 200 ft long) and long slender tail (a very unseal-like feature), but, in particular, by its very sizeable, elongate neck (which bore a noticeable mane in the male). In illustrations depicting its likely appearance in life, it looked very like a mammalian plesiosaur (or a plesiosaurian mammal).

Oudemans even gave this seagoing marvel its very own taxonomic binomial – Megophias megophias, thereby classifying it as a new species within a (now-defunct) genus that had been coined back in 1817 by French-American naturalist and passionate sea serpent investigator Constantine Samuel Rafinesque-Schmaltz in his published description of an uncaptured snake-like marine cryptid responsible for a spate of reported sea serpent sightings off Gloucester, New England, at that time (Megophias translates as 'big snake').

Front cover of the first edition of Oudemans's The Great Sea-Serpent, featuring a gilt representation of the head of the Daedalus sea serpent (public domain)

Front cover of the first edition of Oudemans's The Great Sea-Serpent, featuring a gilt representation of the head of the Daedalus sea serpent (public domain)In 1892, Oudemans published his extensive study and conclusions in his now-classic tome The Great Sea-Serpent, which makes fascinating if frustrating reading. For at the risk of perpetuating further this unintentional bout of alliteration, his resolution of the sea serpent problem was fatally flawed. Anyone reading the vast array of sightings documented by him can readily perceive that the beasts observed belong to a variety of discernibly distinct types. Yet Oudemans, inexplicably, chose to shoe-horn them all into one, resulting in his creation of M. megophias as a 'one-size-fits-all' solution that was doomed to failure when attempting to convince mainstream scientists already highly suspicious of sea serpent reality that it was truly the taxonomic alter ego of this incognito maritime enigma.

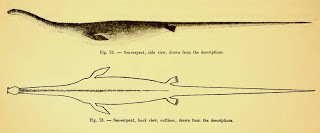

Oudemans's illustrations of his proposed long-necked (and long-tailed) mega-seal Megophias megophias(public domain)