Karl Shuker's Blog, page 29

December 25, 2016

ENTER THE ELEPHANT RAT - A SHUKERNATURE PICTURE OF THE DAY

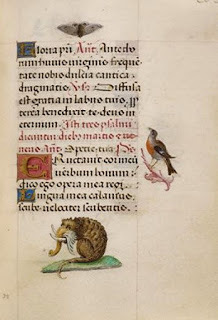

The elephant rat portrayed in the Hours of Joanna the Mad (public domain)

The elephant rat portrayed in the Hours of Joanna the Mad (public domain)It's been quite a while since I last presented a ShukerNature Picture of the Day, but what better way to reintroduce this intermittent feature than with a creature so exotic in form that even though it doesn't exist, it should do!

I am referring to an extraordinary mini-beast of the medieval marginalia, i.e. one of the innumerable creatures of curiosity and composite nature (variously dubbed grotesques if strange or drolleries if humorous) that populate and decorate the edges of illuminated manuscripts prepared many centuries ago by monks and other theological scholars or chroniclers. In a previous ShukerNature blog article (click here ), I documented one particularly intriguing example that has appeared in several such works – the snail-cat. Now, here is another, which for obvious reasons I am herewith officially dubbing the elephant rat.

A snail-cat, depicted in the Maastricht Hours – an illuminated devotional manuscript produced in the Netherlands during the early 1300s (public domain)

A snail-cat, depicted in the Maastricht Hours – an illuminated devotional manuscript produced in the Netherlands during the early 1300s (public domain)As can be seen from the illustration opening this present ShukerNature article and which, to my knowledge, is the only example of such a bizarre composite, the elephant rat deftly combines the head and body of a typical rat with the long trunk and tusks of an elephant, plus a series of odd, knobbly protuberances all over its back that seem entirely peculiar to itself. And as if all of that were not distinctive enough, this remarkable rodent also sports an exceptionally fine set of white bushy side-whiskers.

The illustration in question is from folio 203r ('r' referring to the folio's recto side) of an illuminated manuscript known variously as the Hours of Joanna the Mad or, more formally, as the Hours of Joanna I of Castile. This particular folio is part of a section of the Hoursthat deals with the Office of the Blessed Virgin Mary.

Joanna the Mad, Queen of Castile (from 1504) and Aragon (from 1516); portrait by Juan de Flandes, c.1500 (public domain)

Joanna the Mad, Queen of Castile (from 1504) and Aragon (from 1516); portrait by Juan de Flandes, c.1500 (public domain)Quoting from my earlier snail-cat article:

The Hours of Joanna the Mad is an illuminated book of hours manuscript that had originally been owned by Joanna of Castile (1479-1555), the (controversially) mentally-ill consort of Philip the Handsome, king of Castile. It had been produced for her in the city of Bruges (in what is now Belgium) some time between 1486 and 1506, but is now held as Add. MS 18852 in the British Library. As with so many others of its kind, this illuminated manuscript's margins are plentifully supplied with grotesques and drolleries.

The elephant rat is unquestionably among the most memorable of these, and serves as a good example of both categories by being both strange and humorous.

The complete folio 203r from the Hours of Joanna the Mad containing the elephant rat depiction (public domain)

The complete folio 203r from the Hours of Joanna the Mad containing the elephant rat depiction (public domain)And while on the subject of humour, it is widely believed by researchers of medieval manuscripts that a considerable number of these marginalia monsters arose as nothing more significant or symbolic than attempts by the manuscripts' illuminators and copiers to stave off the boredom induced by very long, tedious hours working upon them by slyly inserting these fantasy creatures as subversive jokes and mockery of the deadly serious nature of the manuscripts' official, devotional content. Or, to put it another way, they are merely medieval doodles, but delightful ones nonetheless, well worth documenting and celebrating in their own right.

Speaking of which: as noted earlier, I am presently aware of only a single elephant rat representation in illuminated manuscripts – the one documented by me here. But as with snail-cats, there may be additional examples tucked away in the margins of others. So if anyone reading this ShukerNature article is aware of such examples, I'd greatly welcome details!

The Hispaniolan solenodon Solenodon paradoxus. Solenodons are quite large but exceedingly-endangered West Indian insectivores that are probably the only modern-day, real-life creatures offering even the remotest outward resemblance to the medieval, imaginary elephant rat (© Sandstein/Wikipedia –

CC BY 3.0 licence

)

The Hispaniolan solenodon Solenodon paradoxus. Solenodons are quite large but exceedingly-endangered West Indian insectivores that are probably the only modern-day, real-life creatures offering even the remotest outward resemblance to the medieval, imaginary elephant rat (© Sandstein/Wikipedia –

CC BY 3.0 licence

)

Published on December 25, 2016 20:29

December 23, 2016

THE HORNED JACKAL AND THE NARRI-COMBOO - A HORN OF CANINE CONTENTION

Sri Lankan golden jackal in Yala National Park (© Thimindu/Wikipedia –

CC BY 2.0 licence

)

Sri Lankan golden jackal in Yala National Park (© Thimindu/Wikipedia –

CC BY 2.0 licence

)It is nothing if not fitting that one of the world's most exotic islands should also lay claim to one of the world's most exotic mystery beasts. The island in question is Sri Lanka (formerly called Ceylon), which is home to an exceedingly curious enigma of the canine kind, known as the horned jackal.

THAT’S WHY THEY CALL HIM THE LEADER OF THE PACK!It was in 1980, when Arthur C. Clarke very briefly alluded to it (together with Sri Lanka's equally contentious devil bird - click here ) in a cryptozoological episode from his television series Arthur C. Clarke's Mysterious World, that I first learned of the horned jackal. I began at once to seek out and amass more information – which included data kindly supplied to me by Arthur C. Clarke himself after I wrote to him explaining my desire to uncover material regarding it – and I was surprised to find that quite a lot of relevant details had indeed been documented, but had hitherto received scant publicity, concerning this remarkable mystery beast.

Sir James Emerson Tennent (public domain)

Sir James Emerson Tennent (public domain)One of the most detailed accounts, complete with illustrations, featured in Sir James Emerson Tennent's excellent book Sketches of the Natural History of Ceylon (1861). Tennent revealed that there is a widespread belief among the Singhalese and Tamil people of Sri Lanka that the leader of each pack of common or golden jackals Canis aureusnaria on this island bears a small horn on its skull. Widely referred to as the narri-comboo or narric-comboo, and generally hidden from view by a tuft of fur, this unexpected horn measures about half an inch long.

According to Tennent, it protrudes from the back of the jackal leader's skull - as depicted by a diagram in his book of a horned jackal's skull formerly preserved at London's Museum of the College of Surgeons. Nevertheless, in certain other books that I have consulted, there have been claims that a horned jackal's narri-comboo protrudes from its brow. Perhaps, therefore, its precise position on the skull varies between individuals. Tennent's book also described and illustrated a specimen of the horny sheath from a narri-comboo that had been presented to him by the then district judge of Kandy, a man called Lavalliere.

Diagram of a horned jackal's skull, including a close-up of the horn's sheath, from Tennent's book (public domain)

Diagram of a horned jackal's skull, including a close-up of the horn's sheath, from Tennent's book (public domain)HORNING IN ON THE LETTER OF THE LAWOne aspect of the narri-comboo that does not vary, however, is the fervent belief shared by Sri Lankan inhabitants throughout the island that this insignificant cranial curiosity is somehow bestowed with extraordinary magical powers - powers that render invincible in all lawsuits anyone fortunate enough to own one of these strange objects.

Moreover, if placed alongside a person's jewellery, a narri-comboo is said to prevent the jewellery from being stolen. And if this horn should somehow be lost it has the very obliging ability to return magically, of its own accord, to its owner. Clearly, no home should be without one!

Head and shoulders portrait of Sir James Emerson Tennant (public domain)

Head and shoulders portrait of Sir James Emerson Tennant (public domain)One of the most entertaining accounts of a narri-comboo's magical (and highly devious) legal machinations appeared in Tennent's book (and should perhaps be borne in mind by anyone with plans to practise law in Sri Lanka!):

A gentlemen connected with the Supreme Court of Colombo has repeated to me a circumstance, within his own knowledge, of a plaintiff who, after numerous defeats, eventually succeeded against his opponent by the timely acquisition of this invaluable charm. Before the final hearing of the cause, the mysterious horn was duly exhibited to his friends; and the consequence was, that the adverse witnesses, appalled by the belief that no one could possibly give judgement against a person so endowed, suddenly modified their previous evidence, and secured an unforeseen victory for the happy owner of the narric-comboo!

Even today, a narri-comboo is greatly prized as a lucky talisman by Sri Lankans, though whether the jackals killed for their horns would share this view is another matter entirely.

Pair of Sri Lankan golden jackals Canis aureus nariaand egrets in Udawalawe National Park, Sri Lanka (© Christina Xu/Flickr/Wikipedia –

CC BY 2.0 licence

)

Pair of Sri Lankan golden jackals Canis aureus nariaand egrets in Udawalawe National Park, Sri Lanka (© Christina Xu/Flickr/Wikipedia –

CC BY 2.0 licence

)THE HORN OF A DILEMMASpecimens such as the erstwhile skull at the College of Surgeons' Museum and the horny sheath given by Lavalliere to Tennent readily confirm the reality of horned jackals, and jackal horns. What has yet to be confirmed, conversely, is the reason why these peculiar structures develop, and whether they are indeed unique to pack leaders.

Logic dictates that the latter aspect of narri-comboo lore must surely owe more to legend than fact, because as pack leadership is not inherited in a predetermined manner from father to one specific male offspring, it is not possible to offer any genetically-based explanation for the supposed restriction of horn development to pack leaders. Similarly, if horn growth occurs in response to some external influence, i.e. stimulated perhaps by a physical blow or injury, one would expect other jackal individuals, not just the leader, to develop horns.

An albino golden jackal (public domain)

An albino golden jackal (public domain)However, externally-induced horn growth may resolve current uncertainty regarding the precise point of origin of the horn on a jackal skull. This is because such a structure might develop from any cranial region that suffered a severe blow. Adventitious horn development via this mechanism has been reliably recorded from other mammal species on occasion.

Possibly the biggest mystery of all, however, is why horned jackals do not seem to have been recorded elsewhere. Canis aureusis distributed widely in Asia and Africa, and has even been reported in eastern Europe, so why do there not appear to be any details of horned specimens outside Sri Lanka? Perhaps there are such records on file somewhere, but they simply haven't been publicised. So if any readers do happen to come across any horned jackal accounts emanating from beyond the shores of former Ceylon, I'd love to hear from you! Meanwhile, further details concerning Sri Lanka's perplexing horned jackal and devil bird can be found in my book From Flying Toads To Snakes With Wings .

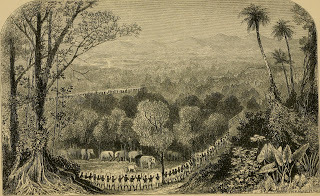

Exquisite engraving constituting the frontispiece to Tennent's above-cited book (public domain)

Exquisite engraving constituting the frontispiece to Tennent's above-cited book (public domain)

Published on December 23, 2016 21:08

December 22, 2016

THE BASILISK AND THE COCKATRICE - MONSTROUS MYTHOLOGY OR REPTILIAN REALITY?

The basilisk (above left) and the cockatrice (right), depictions from medieval bestiaries (public domain)

The basilisk (above left) and the cockatrice (right), depictions from medieval bestiaries (public domain)Two of classical mythology's most feared reptilian monsters were the basilisk and the cockatrice. But were they really nothing more than legends and fables – or could they have been inspired by various real-life creatures?

THE BASILISK

Today, the only basilisks known to herpetologists are those very eyecatching but totally harmless Latin American iguanid lizards of the genus Basiliscus, famous for their remarkable ability to sprint bipedally across the surface of ponds – hence their lesser-known alternative name of Jesus Christ lizards. However, they derive their more familiar name from a very different, allegedly lethal reptile from the Old World, and which supposedly existed there during medieval times – the original basilisk.

The harmless real-life basilisk lizard (© Markus Bühler)

The harmless real-life basilisk lizard (© Markus Bühler)One of the earliest references to it appeared in Pliny the Elder's magnum opus Natural History (c.77-79 AD). On first sight, this inconspicuous serpent dragon, just 3 ft or so long, simply resembled a slender brown snake. On closer inspection, however, it could be seen to bear a regal crown of gold upon its head (hence 'basiliskos' - Greek for 'little king'). And when it moved, it raised much of its body vertically upwards in a proud, fearless stance, eschewing the lowly belly-crawling mode of locomotion typifying ordinary serpents.

The basilisk had every reason to be fearless. According to popular lore, its merest glance was enough to kill almost any living creature instantly – including another basilisk (and even itself if it somehow caught sight of its own reflection). The tiniest drop of venom dribbling from its jaws was ample to poison the earth upon which it fell, or the water into which it dripped. And the faintest breath that it exhaled was sufficient to transform the land for many miles in every direction from fertile pastures into arid desert. Indeed, the very existence of the deserts where the basilisk lived, in North Africa and Arabia, was said to have been directly caused by its baleful presence.

In short, the basilisk was virtually invulnerable. Thankfully, however, it was also very uncommon, and could be warded off with a sprig of the rue plant. Moreover, it could be killed outright by the rank odour of urine from a weasel – an aspect of the basilisk legend that may have been inspired at least in part by tales emanating from the Orient of cobras confronted and dispatched by mongooses.

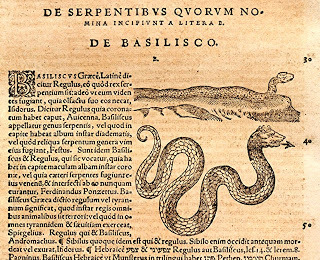

Basilisk, in Conrad Gesner's Historiae Animalium, vol 5, 1587 (public domain)

Basilisk, in Conrad Gesner's Historiae Animalium, vol 5, 1587 (public domain)The basilisk's origin was just as uncanny as its appearance and capabilities, and explained why this diminutive but much-dreaded monster was so rare. A basilisk was only created if the egg of a serpent were hatched by a rooster (cockerel) – a bizarre event which (thankfully!) was hardly likely to happen very frequently.

Despite its formidable nature, medieval alchemists were very keen to possess the ashes of a dead basilisk, because they believed that this scarce, precious matter could transmute silver into gold. Some scholars, such as Theophilus Presbyter (fl. c.1070-1125), even believed that a basilisk could be magically created via a detailed recipe of ingredients and reactions, and that the resulting creature would convert copper into Spanish gold.

Although traditionally said to inhabit the deserts of North Africa and the Middle East, the basilisk could claim a number of counterparts elsewhere in the world too. For example, in bygone ages the town of Baunei in the province of Ogliastra on the Italian island of Sardinia was terrorised by a basilisk-like monster that lived in the bushes there and was known as the scultone or ascultone. Just like the basilisk, its gaze was sufficient to kill anyone or anything that looked directly at it, but unlike the basilisk it was immortal. Nevertheless, Peter the Apostle finally managed to rid Baunei of this menace using a mirror, though the precise manner in which he accomplished the feat remains unclear.

Scultone (public domain)

Scultone (public domain)In Gambia, Senegal, Guinea, and Guinea-Bissau in West Africa, traditional lore tells of a greatly-feared serpent dragon known as the ninki-nanka. Not only did it possess supernatural powers, it also concealed a precious diamond inside its head, from which it drew these powers. Moreover, echoing the odd manner in which a basilisk was created, a ninki-nanka was only hatched from an egg that was present in the very centre of a clutch of normal python eggs.

South America's basilisk equivalent, the basilisco, was toad-like rather than serpentine, and could only be hatched from a black egg. Accounts of this creature come from Santiago del Estero, the Mapuche area, and the northwestern region of Argentina.

Is it conceivable, however, that belief in such bizarre, fictitious monsters as the basilisk and its cohorts elsewhere around the world was derived at least in part from sightings of unusual but genuine creatures?

Ringhals spitting cobra Hemachatus haemachatus (© Lee R. Berger/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 2.5 licence

)

Ringhals spitting cobra Hemachatus haemachatus (© Lee R. Berger/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 2.5 licence

)The original basilisk, supposedly inhabiting North Africa's deserts, and whose merest glance could kill, may have been inspired by a very specific and unusual type of real-life snake – the spitting cobra. Several species are recognised (some of which are native to North Africa), and all of them incapacitate their prey or potential aggressors by spitting accurately, and from some distance away, a stream of corrosive venom into their eyes (click here to watch a short YouTube video of a spitting cobra doing precisely this to a snake handler - happily, the handler is wearing protective glasses!). Early travellers' tales of this remarkable ability could have been elaborated over generations of retelling into the basilisk's fatal glance.

In addition, the deserts of North Africa and the Middle East are home to a small, harmless species of colubrid snake known as the awl-headed sand snake Lytorhynchus diadema. The diadem-like markings upon its head and its yellowish-brown body colouration recall traditional descriptions of the basilisk's appearance and may therefore have helped to inspire belief in the latter.

Incidentally, a spitting cobra brought to England during the early 1600s as an exotic pet or exhibit that later escaped into the countryside could provide a plausible identity for a 10-ft-long serpent dragon reported from St Leonard's Forest, near Horsham, West Sussex, in August 1614. According to a pamphlet circulated at that time (which is the original source of this report and was subsequently republished in the Harleian Miscellany, 1744-1753), it killed two people, two dogs, and several cattle by spitting venom at them, but did not try to devour them.

Illustration of the St Leonard's Forest dragon from the original pamphlet of 1614 (public domain)

Illustration of the St Leonard's Forest dragon from the original pamphlet of 1614 (public domain)Nor are spitting cobras the only potential link between the basilisk of folklore and certain unexpected creatures of fact. Chickens are often infected with parasitic gut-inhabiting worms, including the ascarid roundworm Ascaris lineata, a nematode species that can grow to a few inches in length (a related giant species in humans can grow to over 1 ft in length!). They are often passed out of the bird's gut when it defaecates. Unlike in mammals, however, the bird's gut and its reproductive system share a common external passageway and opening – the cloaca. Sometimes, therefore, an ascarid worm ejected from the gut finds its way into the bird's reproductive system rather than being excreted into the outside world, and moves into the oviduct. Once here, however, it becomes incorporated into the albumen of an egg, inside which it remains alive yet trapped when the egg is laid. But as soon as the egg is broken open to eat by some unsuspecting diner, the worm wriggles its way out of it to freedom, scaring the diner and perpetuating the myth of the basilisk in the process!

On 3 March 2012, Copenhagen University zoologist Lars Thomas left a message below a short basilisk post of mine (click here ) on my Eclectarium of Doctor Shuker blog, informing me of his own direct experience with this fascinating phenomenon:

I suppose you know, that some legends say young basilisk "worms" could sometimes be found in chicken eggs. Indeed if you found a worm in an egg, not so very long ago, old folks would tell you it was a basilisk, and tell you how to get rid of it. When I was 8 years old, I was on holiday at my aunt who had a small farm. One day I was helping her in the kitchen cracking eggs, and in one of them was a worm. Auntie told me it was a young basilisk, and that I should very carefully take it out in her garden and bury it, and then walk three times around the filled up hole. So I did, but not before making a drawing of the egg and the worm. I still got the drawing.

Ascaris

, a parasitic nematode or roundworm (public domain)

Ascaris

, a parasitic nematode or roundworm (public domain)Judging from this telling little vignette, burying traditional belief in basilisks is clearly much harder to do than burying the supposed basilisk itself!

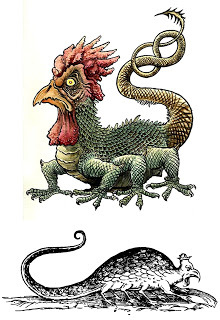

THE COCKATRICE

During the Middle Ages, the small yet deadly basilisk underwent a very dramatic transformation in mythology, metamorphosing into a much bigger, truly grotesque type of two-legged, wyvern-like dragon known as a cockatrice, However, there is much confusion and terminological interchange relating to this, with many unequivocal cockatrices often being referred to incorrectly as basilisks.

Cockatrice statue at Trsat Castle in Rijeka, Croatia (© Georges Jansoone/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 3.0 licence

)

Cockatrice statue at Trsat Castle in Rijeka, Croatia (© Georges Jansoone/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 3.0 licence

)Muddying the mythological waters even further, moreover, an intriguing, seemingly intermediate version with multiple limb pairs and a horizontal body but a wattled, cockerel-like head (yet still bearing a regal crown) was also popularly illustrated in bestiaries during that time, and was variously referred to as a basilisk or as a cockatrice, depending upon the chronicler in question.

Swedish artist and film-maker Richard Svenson's vibrant, colourful representation of the intermediate, multi-limbed stage in the basilisk-to-cockatrice transformation (above), inspired by bestiary depictions of it (e.g. below, from Serpentum et Draconum Historiae by Ulisse Aldrovandi, 1640) (© Richard Svensson / public domain)

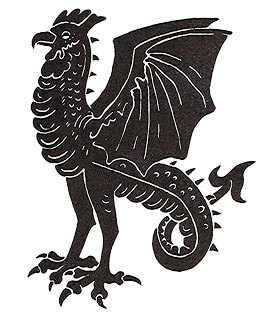

Swedish artist and film-maker Richard Svenson's vibrant, colourful representation of the intermediate, multi-limbed stage in the basilisk-to-cockatrice transformation (above), inspired by bestiary depictions of it (e.g. below, from Serpentum et Draconum Historiae by Ulisse Aldrovandi, 1640) (© Richard Svensson / public domain)During its transformation from the basilisk, the cockatrice gained a pair of large bat-like wings, a long coiled tail (still covered in scales but often terminating in a sharp sagittal tip), and a single pair of sturdy rooster-like legs that enabled it to walk upright. Furthering its cockerel parallels, however, it also sported a coxcomb on its head, a pair of pendulous facial wattles, a pointed horny beak, sometimes a covering of feathers upon its body, and even the ability to crow like a farmyard rooster too.

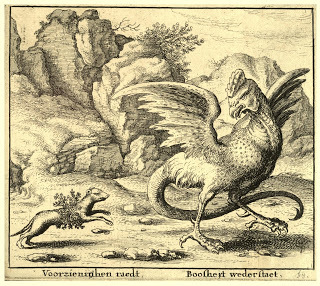

Cockatrice fleeing from a weasel wrapped in rue, illustrated by Wenceslaus Hollar, 1600s (public domain)

Cockatrice fleeing from a weasel wrapped in rue, illustrated by Wenceslaus Hollar, 1600s (public domain)Even so, this weird avian reptile (or reptilian bird?) retained the basilisk's deadly gaze, its dread of weasels and rue, and also, albeit in a reversed version, its bizarre mode of creation. Now, one of these monstrous entities would only arise if a round leathery shell-less egg laid by a seven-year-old cockerel when the dog star Sirius was in the ascendant was hatched by a toad in a dung heap. Although such an occurrence may seem highly unlikely, cockatrices were reported not just in North Africa and Arabia like their basilisk antecedent but also widely through Europe, including several examples from Britain.

Cockatrice in Raoul Lefèvre's tome Histoires de Troyes Belgique, 1400s (public domain)

Cockatrice in Raoul Lefèvre's tome Histoires de Troyes Belgique, 1400s (public domain)One of the most recent of these was the Renwick cockatrice. Crowing loudly, this bat-winged horror, black in colour but sporting facial wattles and a coxcomb, reputedly emerged from the foundations of a church being demolished by workmen in the Cumbrian village of Renwick in 1733. Happily, the monster was dispatched by local hero John Tallantine with a sturdy wooden lance hewn from a rowan tree - famed for its magical, evil-repelling properties. If such an event truly took place, might the offending creature have been merely a large bat, whose proportions were duly exaggerated and elaborated in subsequent retellings of the incident?

Is this what the so-called Renwick cockatrice looked like? (public domain)

Is this what the so-called Renwick cockatrice looked like? (public domain)Iceland is not a country well known for dragon legends, but its traditional lore does lay claim to its own version of the cockatrice – a deadly creature called the skoffin. It has a very curious origin – the highly unlikely outcome of a liaison between a male fox and a female cat (the offspring of the reverse pairing – between a tom cat and a vixen – is called a skuggabaldur, and is just as ferocious as a skoffin). Similar in form to the cockatrice, albeit furry rather than feathery, the skoffin also shared the latter's lethal gaze - and could even kill another skoffin simply by looking it in the eye. Otherwise, it was virtually invincible, unless shot with a silver button upon which the sign of the Cross had been inscribed (click here to see a depiction of a skoffin as featured on an Icelandic postage stamp).

Cockatrice in German Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher's Mundus Subterraneus, 1665 (public domain)

Cockatrice in German Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher's Mundus Subterraneus, 1665 (public domain)Continuing this intriguing link between cockatrices and Christianity, it may come as a surprise to learn that the cockatrice was formerly mentioned no less than four times within the Old Testament of the Bible, three of these mentions occurring in the Book of Isaiah, and the fourth in the Book of Jeremiah. The Hebrew terms that were once translated as 'cockatrice' were 'Tsepha' and 'Tsiphoni', but in modern-day versions they are translated as 'viper' or 'adder' instead, thus explaining the cockatrice's disappearance from this holy book.

Cockatrice illustrated in a German manuscript from 1507 (public domain)

Cockatrice illustrated in a German manuscript from 1507 (public domain)Iceland is not unique in boasting its own specific form of cockatrice. So too does Korea – the gye-ryong ('chicken-dragon'). Just as Oriental dragons are generally more benevolent than malevolent, however, so too is this Korean cockatrice, often pulling the chariots of notable legendary heroes or those of their parents.

Cockatrice, by Friedrich Johann Justin Bertuch, 1806 (public domain)

Cockatrice, by Friedrich Johann Justin Bertuch, 1806 (public domain)Thanks to its rooster-like coxcomb, wattles, feathers, and crowing cry, the cockatrice was a very unusual dragon. And as befitting this, it may well have had a comparably odd origin in the real world.

A very gallinaceous faux cockatrice participating as the Basilisk of Reus in the 2016 Cercavila de les festes del Barri Gòtic, in Barcelona, Spain (© Pere López Brosa/Wikipedia – CC BY-SA 3.0 licence)

A very gallinaceous faux cockatrice participating as the Basilisk of Reus in the 2016 Cercavila de les festes del Barri Gòtic, in Barcelona, Spain (© Pere López Brosa/Wikipedia – CC BY-SA 3.0 licence)Sometimes, an otherwise normal hen develops an internal tumour that stimulates the development of male hormones. These in turn induce the development of male secondary sex characteristics – namely, the rooster's coxcomb, wattles, crowing cry, and even on occasion its plumage. Yet it still lays eggs. In bygone, superstition-laden times, the mere sight of such a bizarre curiosity as one of these partial sex-change 'father hens' would have been enough to initiate imaginative fear-laden tales of the dreaded cockatrice.

Bristol Post

newspaper report concerning a sex-change chicken - click it to read it (© Bristol Post, reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial, educational/review basis only; report's date of publication currently unknown to me – any details would be very welcome, so that I can attribute it fully)

Bristol Post

newspaper report concerning a sex-change chicken - click it to read it (© Bristol Post, reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial, educational/review basis only; report's date of publication currently unknown to me – any details would be very welcome, so that I can attribute it fully)THE BASILISK AND COCKATRICE IN CRYPTOZOOLOGY?

Finally: In modern times, there have been several eyewitness reports emanating from isolated regions of verdant vegetation amid the otherwise arid desert zones of Morocco and Tunisia that tell of very large snakes bearing a crest or long 'hair' on their head. Such reports readily recall the legendary basilisk, in terms of both location and these snakes' morphology, so could they explain this much-dreaded reptile? Assuming that these snakes are themselves real, it has been suggested that they may constitute relict populations of pythons, analogous to isolated populations of desert-dwelling crocodiles, and that their supposed crests or hair are merely segments of incompletely-shed skin.

Crested mystery snakes are even more commonly reported in tropical Africa, where they have a wide variety of local names, of which the most familiar is the inkhomi ('killer'), but in English parlance they are generally referred to as crowing crested cobras (see also a previous ShukerNature blog article of mine surveying these ophidian enigmas – click here ). They are said to sport a bright-red rooster-like coxcomb (but pointing forwards rather than back) and facial wattles too, and to crow just like a rooster as well – all of which is very reminiscent of the basilisk's transformed equivalent, the cockatrice. In 1944, Dr J. Shircore from Malawi published a detailed description of what he believed to be the fleshy coxcomb and part of the neck from one of these snakes, but the current whereabouts of this potentially-valuable specimen is not known.

Crowing crested cobra representation, based upon eyewitness reports (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Crowing crested cobra representation, based upon eyewitness reports (© Dr Karl Shuker)Equally noteworthy is a published report by John Knott from September 1962 in which he recalled how, driving home one evening in late May 1959 from Binga, in the Kariba area of what was then Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), he inadvertently ran over a large, jet-black snake roughly 6 ft long, mortally wounding it. Knott cautiously stepped out of his vehicle to take a closer look at the snake, and was amazed to see that it bore a distinct crest upon its head, perfectly symmetrical in shape, and capable of being erected by way of five internal prop-like structures. This certainly does not sound like a piece of unshed skin but rather like a true crest, yet no known species of snake possesses one.

Remarkably, a very similar but somewhat shorter mystery snake, complete with coxcomb, wattles, and crowing ability, has been reported in modern times, and by native and Western observers alike, on the West Indian islands of Jamaica and Hispaniola. If such snakes as these on record from Africa and the Caribbean are genuine, they may well have assisted in inspiring the cockatrice legend.

A magnificent heraldic cockatrice (public domain)

A magnificent heraldic cockatrice (public domain)They may no longer possess the lethal talents originally ascribed to them, but judging from reports such as those noted above, it may be somewhat premature to discount the basilisk and the cockatrice as wholly imaginary after all.

Cockatrice (labelled as as basilisk) and weasel, in Bestiary, Royal MS 12 C XIX, 1200-1210 (public domain)

Cockatrice (labelled as as basilisk) and weasel, in Bestiary, Royal MS 12 C XIX, 1200-1210 (public domain)This ShukerNature blog article is adapted from the relevant sections of my newest, massively-comprehensive dragon book Dragons in Zoology, Cryptozoology, and Culture – a must-read for all draconophiles everywhere!

Published on December 22, 2016 20:08

December 20, 2016

THE TURKEY, THE TAPESTRY, AND SOME FOWL PLAY IN THE CATHEDRAL!

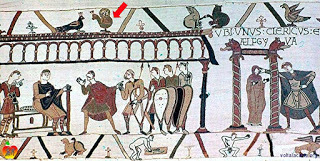

Section of the Bayeux Tapestry depicting the alleged turkey (red-arrowed, in top border, left of centre), with a blue peacock to its immediate left - click picture to enlarge it (public domain)

Section of the Bayeux Tapestry depicting the alleged turkey (red-arrowed, in top border, left of centre), with a blue peacock to its immediate left - click picture to enlarge it (public domain)Welcome to ShukerNature's contribution to the festive season, as the focus of this present article of mine is that most archetypal of Christmas avians, the turkey.

Although today they are familiar in domestic form throughout the world, turkeys are native New Worlders. Two species are recognised - the ocellated turkey Agriocharis ocellata, which is confined to Central America; and the common or North American turkey Meleagris gallopavo, which in the wild state occurs in the southeastern U.S.A.and Mexico. The domestic turkeys nowadays raised throughout the western world are descended from a southern Mexican subspecies of the common turkey, which first became known to Europeans when the Spanish conquistadors invaded Mexico during the first half of the 1500s, discovered domestic turkeys maintained by the Aztecs there, and brought some back with them to Spain. That is the official history of the turkey's arrival in the Old World, but there is a mystifying anachronism on record that offers up a very different scenario for consideration.

Measuring almost 230 ftlong and 20 intall, the Bayeux Tapestry, embroidered in southern England between 1066 and 1077, depicts in great detail the events leading up to the Norman invasion of England and the Battle of Hastings in 1066, and as such it is a highly significant historical document. This is why, therefore, one of the birds portrayed in the rows of creatures decorating the tapestry's borders has attracted appreciable historical (as well as cryptozoological) attention - because it bears somewhat of a resemblance to a turkey. Yet accepted history dictates that turkeys did not reach European shores from the New World for almost another 500 years.

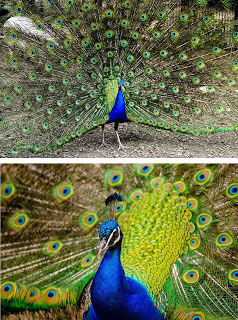

Blue peacock with ornamental train fully expanded and displayed (public domain); and a close-up of its head, revealing its characteristic crest of racquet-tipped plumes (public domain)

Blue peacock with ornamental train fully expanded and displayed (public domain); and a close-up of its head, revealing its characteristic crest of racquet-tipped plumes (public domain)Some historians have sought to reconcile this chronological discrepancy by claiming that the bird in question is not an accurate portrait of a turkey but is merely a poor depiction of a male blue peafowl Pavo cristatus (i.e. a peacock), which was certainly a popular dish, especially among the wealthy, in Europe at the time of the Bayeux Tapestry's creation (and for several subsequent centuries too).

Others, conversely, have boldly suggested that if the Vikings did indeed reach North America during the early years of the 11th Century AD, i.e. several centuries before Christopher Columbus (not to mention the Spanish conquistadors), perhaps they returned to Europe with some turkeys. This would therefore explain how an exclusively New World bird could appear on the Bayeux Tapestry later that same century.

Having closely scrutinised this controversial depiction, I remain somewhat nonplussed concerning the bird's identity, as none of the options on offer seems wholly satisfying.

A domestic male turkey, descended from the common or North American wild turkey (© Dr Karl Shuker)

A domestic male turkey, descended from the common or North American wild turkey (© Dr Karl Shuker) Certainly, its body and head appear burlier than those of a typical blue peacock, and its tail is more reminiscent of a male turkey's when outsplayed than the disproportionately huge, arching train of a blue peacock. There is even a degree of similarity to the adult male of the capercaillie Tetrao urogallus, Europe's largest species of grouse, which existed in Britainat the time of the Norman Conquest (centuries later it became extinct here but has been successfully reintroduced into Scotland).

Yet the Bayeux mystery bird's head bears the blue peafowl's characteristic crest of racquet-tipped plumes – conspicuous only by their absence in turkeys and capercaillies (the latter species is also much darker than the Bayeux bird) – unless this feature was mistakenly added by the Bayeux illustrator, basing his depiction perhaps upon a faulty verbal description influenced by a peacock's morphology rather than upon firsthand sight of a turkey?

It might even represent an entirely fictitious, composite bird; after all, this elaborate tapestry contains a number of decidedly strange-looking creatures that seemingly owe little allegiance to the real world.

An adult male capercaillie (© David Palmer/Wikipedia - CC BY 2.0 licence)

An adult male capercaillie (© David Palmer/Wikipedia - CC BY 2.0 licence)A further complication with the Bayeuxcase inadvertently stemmed from a short article by Maris Ross, published in London's Daily Mail newspaper on 31 August 1991, which briefly alluded to the turkey mystery. Accompanying Ross's article was a sketch prepared by one of the Daily Mail's resident cartoonists, Haro, depicting in his own distinctive, readily recognisable style an 11th-Century man with a turkey.

Amusingly, albeit regrettably, Haro's sketch has since been reproduced in more than one account of the alleged Bayeuxturkey under the mistaken assumption that it is a direct representation of this bird as it is depicted in the tapestry!

Indeed, the late anomalies chronicler William Corliss even lamented in an article for the May-June 1992 issue of his Science Frontiers periodical that a specific search for this particular illustration within the Bayeux Tapestry had been conducted but had failed to find it – which is hardly surprising! In the January-February 1996 issue of this same periodical, Corliss revealed that via a personal communication of 2 November 1995, the person who had informed him about the vain search had been Erik Ringdal Sørensen.

The short London Daily Mail article containing Haro's turkey-featuring illustration (© Daily Mail/Haro – reproduced here solely for educational, review purposes on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis only)

The short London Daily Mail article containing Haro's turkey-featuring illustration (© Daily Mail/Haro – reproduced here solely for educational, review purposes on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis only)Notwithstanding such unfortunate confusion, the Bayeux turkey remains a valid mystery, whereas a second instance of controversial turkey depictions, featuring the infamous examples formerly decorating Schleswig's stately cathedral in Germany, was ultimately exposed as a turkey (or canard?) in every sense of the word!

The walls of Schleswig Cathedral in Germany are richly decorated with medieval murals. One of these, supposedly dating from around 1280, included a horizontal row of four unmistakable representations of a domestic turkey, complete with pendant beak wattle (snood), upraised fanned tail feathers, and large broad wings.

As with the Bayeux depiction, however, if these were genuine it would thus suggest that turkeys reached the Old World several centuries before their official arrival here with the conquistadors.

Two of the four turkey images formerly decorating Schleswig Cathedral (© Uli Poppe/Wikipedia -

CC BY-SA 3.0 licence

)

Two of the four turkey images formerly decorating Schleswig Cathedral (© Uli Poppe/Wikipedia -

CC BY-SA 3.0 licence

)Curiously, no-one had noticed the turkey depictions in Schleswig Cathedral until after World War II, but during the early 1950s the reason for this odd oversight, and the even odder presence of the turkey depictions here anyway, were sensationally revealed - during an art forgery trial.

The accused in what became a truly sensational trial lasting from 10 August 1954 to 26 January 1955 was German painter Lother Malskat, who not only confessed to the charges brought against him, but also conceded that he was responsible for the Schleswig turkeys too!

Apparently, Malskat had been restoring some of the cathedral's original 13th-Century murals just prior to World War II, and while doing so he had spotted an outline that reminded him of a turkey - so he skilfully painted one into the mural, followed by three others, thereby yielding a distinctive horizontally-arranged quartet of these zoogeographically anomalous birds!

A beautiful vintage illustration from 1894 depicting Schleswig Cathedral (public domain)

A beautiful vintage illustration from 1894 depicting Schleswig Cathedral (public domain)With the onset of the war, no-one had spotted Malskat's anachronistic additions straight away, so if it had not been for the forgery case, his turkeys may still have been perplexing scholars of art, zoology, and history even today. Instead, once his foul – or fowl! – play had been exposed there (which earned him a sentence of 18 months in jail), the turkeys were swiftly expunged from the cathedral's walls and more appropriate depictions painted in their stead by other, more reputable art restorers.

(For a very comprehensive and thoroughly fascinating Art & Antiques article from February 2012 by art historian Jonathan Keats documenting the extraordinary history behind Malskat's career and creations as an art forger, click here .)

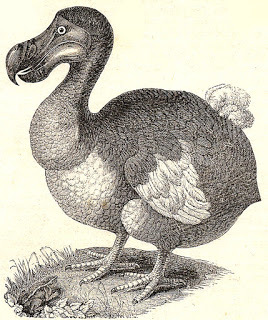

As for the Bayeux mystery bird: if we are considering the prospect of an exotic species having been brought to England by early maritime explorers from some faraway native homeland several centuries before it had even been officially discovered in that land by western naturalists, there is one additional possibility that I have never previously seen put forward but which must surely be worth mulling over. Or, to put it another way: is it just me, or, if we ignore its crest, does the alleged Bayeux turkey look more than a little like a Mauritius dodo??

19th-Century engraving of the Mauritius dodo Raphus cucullatus, first officially recorded in 1598, by some Dutch sailors, and extinct by the end of the following century (public domain)

19th-Century engraving of the Mauritius dodo Raphus cucullatus, first officially recorded in 1598, by some Dutch sailors, and extinct by the end of the following century (public domain) This ShukerNature blog article is an updated, expanded excerpt from my book Mysteries of Planet Earth: An Encyclopedia of the Inexplicable .

Published on December 20, 2016 17:53

December 18, 2016

FIRE BEASTS, LIGHTNING BEASTS, AND THE ELEPHANT OF TIAHUANACO - INVESTIGATING AN ANOMALOUS ARCHAEOLOGICAL ARTEFACT FROM SOUTH AMERICA

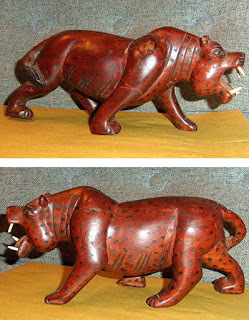

Side-view photograph of the enigmatic Tiahuanaco elephant figurine (reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Free Use basis only; copyright holder currently unknown to me, despite considerable efforts made to trace details)

Side-view photograph of the enigmatic Tiahuanaco elephant figurine (reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Free Use basis only; copyright holder currently unknown to me, despite considerable efforts made to trace details)They do say that all good things come in threes. So, in the hope that you found interesting the two previous hitherto-uninvestigated examples of putative cryptozoological artefacts that I documented recently on ShukerNature (click here and here ), there now follows a third one – and this time hailing not from Africa but instead from South America.

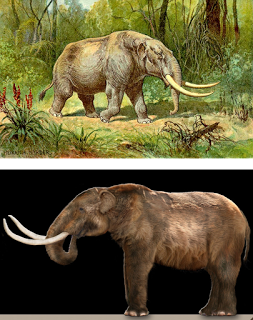

Over the years, there have been several well-publicised and often-republished accounts of mysterious creatures allegedly sighted in various parts of the New World that supposedly resembled the American mastodont Mammut americanum. This was a very large, long-headed, long-tusked relative of modern-day elephants, but it officially became extinct around 11,000 years ago.

Vintage restoration of the American mastodont in life by Heinrich Harder (top) and modern-day version (bottom) (public domain / © Dantheman9758/Wikipedia –

CCBY-SA 3.0 licence

)

Vintage restoration of the American mastodont in life by Heinrich Harder (top) and modern-day version (bottom) (public domain / © Dantheman9758/Wikipedia –

CCBY-SA 3.0 licence

)None of these particular reports, however, have withstood close cryptozoological scrutiny. But also on file are a number of less familiar ones that may conceivably indicate – or not – the late survival of mastodonts, or something quite like them. Of these latter reports, there is one in particular that especially fascinates me, featuring as it does an artefact that is very elegant but also very enigmatic – on account of how little I have been able to discover concerning it. Consequently, I am presenting herewith my investigation and findings concerning it, in the fervent hope that bringing this remarkable item's very intriguing if decidedly abstruse history to wider attention will assist in eliciting additional information.

The artefact in question is a small black-ware pottery figurine of an instantly-recognisable elephant, complete with a pair of large round flaring ears, four sturdy legs, a downward-curving trunk, and a pair of short tusks. Yet it was unearthed at Tiahuanaco (aka Tiwanaku), a pre-Columbian archaeological site near Lake Titicaca in western Bolivia, South America, where all manner of items have been found that originate from the once-mighty Tiahuanacan empire, which had existed there from 300 AD to 1,000 AD.

Front-view photograph of the enigmatic Tiahuanaco elephant figurine (reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Free Use basis only; copyright holder currently unknown to me, despite considerable efforts made to trace details)

Front-view photograph of the enigmatic Tiahuanaco elephant figurine (reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Free Use basis only; copyright holder currently unknown to me, despite considerable efforts made to trace details)I first learnt of this figurine from an online Russian forum called Laiforum, one of whose members (with the user name Mehanoid) had posted there on 15 April 2016 an excellent side-view photograph of it with a link to a Russian video on YouTube. When I accessed this video (currently still online - click here to view it), I discovered that it had been uploaded on 7 April 2016 by an association called ProtoHistory, and was a filmed lecture given by Russian historian Andrey Zhukov to publicise his new book, Secrets of Ancient America (2016).

Just a few seconds after the first 27 minutes of the video have played, two photos of the elephant figurine are briefly screened. One is the side-view picture posted on Laiforum, the other is a front-view shot. Moreover, the side-view picture is then re-screened but this time revealing that it is actually part of a page from what appears to be an article dealing with it, written in Spanish. Using a screen-shot of this, I have been able to confirm that it is one of at least two pages written in Spanish and illustrated with several other animal-themed Tiahuanacan black-ware pottery figurines.

Screenshot of the two above-noted pages from the unsourced Spanish article (reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Free Use basis only; copyright holder currently unknown to me, despite considerable efforts made to trace details)

Screenshot of the two above-noted pages from the unsourced Spanish article (reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Free Use basis only; copyright holder currently unknown to me, despite considerable efforts made to trace details)However, I have not succeeded so far in obtaining any additional details concerning the article itself – no author name, article title, periodical title, or date of publication. Nevertheless, the text present just on these two pages is nothing if not intriguing, because of the very unusual identity that is being considered there in relation to the Tiahuanaco elephant figurine.

Prior to its connection to North America when the isthmus of Panama was formed around 3 million years ago, South America had been an island continent for millions of years, just like Australia. And, again just like Australia, during that vast time period its mammalian contingent had given rise to several entirely new, unique lineages, especially among its ungulates. But due to convergent evolution, outwardly they came to look very like the respective ungulates elsewhere in the world whose ecological niches they were occupying in South America. Chief among these Neotropical impersonators were the horse-like and camel-like litopterns, plus the ox-like and hippopotamus-like notoungulates.

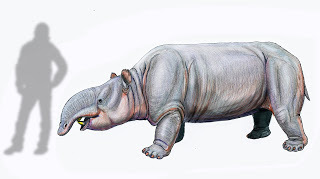

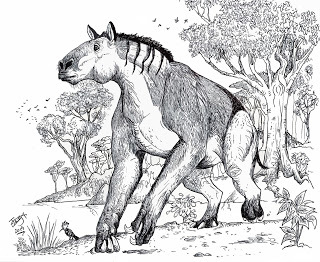

Less familiar but no less distinctive, however, were the pyrotheres ('fire beasts', so-named because the first documented fossil specimens had been excavated from an ancient volcanic ashfall). In their most famous representative, Pyrotherium romeroi of Argentina, the nasal trunk, long head, general body shape, and overall size (up to 10 ft long and standing 5 ft at the shoulder) rendered it more than a little like a mastodont, or even a very big tapir - both groups, incidentally, actually occurring first in North America, not reaching South America prior to the isthmus of Panama, thus enabling pyrotheres to occupy their niches here.

Modern restoration of the likely appearance in life of Pyrotherium romeroi (© DiBGD/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 4.0 licence

)

Modern restoration of the likely appearance in life of Pyrotherium romeroi (© DiBGD/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 4.0 licence

)Moreover, certain reconstructions of their likely appearance in life have given various large pyrotheres a somewhat pachydermesque form, complete with large ears, sizeable tusks, and a fairy long trunk. Could it be, therefore, as speculated in the Spanish article containing its two photos, that the Tiahuanaco elephant figurine was actually not an elephant at all but instead a late-surviving pyrothere?

Unfortunately, whereas certain litopterns and notoungulates are indeed known from documented fossil remains to have survived to at least as recently as the Pleistocene's close just over 11,000 years ago, the youngest pyrothere fossils currently on record are over 20 million years old, dating back to the Oligocene. Moreover, even the most proboscidean-inspired pyrothere restorations are still far less elephant-like and much more mastodont-like than the Tiahuanacan figurine, so it seems prudent to assume that the latter does indeed represent an elephant rather than a pyrothere.

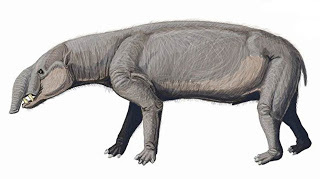

Modern restoration of the likely appearance in life of Astrapotherium (© Dmitry Bogdanov/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 3.0 licence

)

Modern restoration of the likely appearance in life of Astrapotherium (© Dmitry Bogdanov/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 3.0 licence

)Worth noting here, incidentally, is that South America was once home to yet another taxonomic group of vaguely proboscidean ungulates – the astrapotheres ('lightning beasts'), which ultimately died out around 12 million years ago during the mid-Miocene epoch.

Their most famous representative was Astrapotherium, which was slightly smaller than the pyrothere Pyrotherium, but, as with the latter beast, may have looked somewhat mastodont-like or even tapir-reminiscent in life, courtesy of its elongated head, nasal trunk, and tusks (very long in certain other astrapotheres, particularly Colombia's snorkel-trunked, short-legged, long-bodied Granastropotherium snorki). However, its ears were only small, and it certainly would not have resembled the mystifying Tiahuanaco elephant figurine.

Modern restoration of the likely appearance in life of Granastropotherium snorki(© Rextron/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 3.0 licence

)

Modern restoration of the likely appearance in life of Granastropotherium snorki(© Rextron/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 3.0 licence

)Of course, assuming that the latter figurine is indeed a depiction of a true elephant (and it certainly looks like one, albeit a somewhat short-trunked individual), as opposed to a pyrothere, astropothere, or mastodont, the inevitable question requiring an answer is how can its origin at Tiahuanaco be explained?

Might it simply be a recently-created fake, therefore, as has already been postulated by many authors with regard to the depictions of comparably out-of-place and/or anachronistic animals depicted upon the highly controversial Ica stones of Peru and via the equally contentious Acámbaro figurines of Mexico? Or could its existence constitute evidence of pre-Columbian trading and visitations by Libyans and other travellers from the Old World, as has been repeatedly proposed down through the years by a number of researchers and chroniclers?

Clearly, the very perplexing Tiahuanaco elephant figurine deserves a detailed study, and I would be very grateful to any readers who can offer me further information concerning it, including its current whereabouts plus the name and date of the periodical in which the Spanish article discussing it appeared.

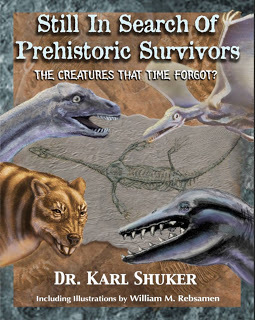

This ShukerNature blog article is excerpted from my newly-published mega-book Still In Search Of Prehistoric Survivors .

Published on December 18, 2016 07:11

December 17, 2016

TIME TO MEET AND GREET MY HIPPO-CAT! ANOTHER MYSTIFYING CRYPTO-CARVING(?) FROM AFRICA

Side views of my African 'hippo-cat' wooden carving – please click to enlarge (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Side views of my African 'hippo-cat' wooden carving – please click to enlarge (© Dr Karl Shuker)Hot on the heels of the scaly mokele-mbembe-reminiscent mystery statuette documented by me in my previous ShukerNature post (click here ) just a few days ago, here is a second incongruous iconographical object of the putatively cryptozoological kind. Yet whereas the only way for me to examine the former example directly would be to visit the Rosminian Missionary Fathers at Glencomeragh House, Clonmel, in County Tipperary, Ireland, where it is held, I don't have to travel anywhere near as far from my home in the West Midlands, England, in order to examine this latest item. In fact, I don’t even have to leave my home at all in order to do so, because it is right here in front of me, ensconced in my study. But to begin at the beginning…

Roughly 5-6 years ago, when my mother Mary Shuker was alive and still in good health, we would travel frequently and widely across England and Wales together visiting antique shops, collectors fairs, bric-a-brac markets, car boot sales, etc, where I would always be keeping a sharp lookout for anything unusual and potentially cryptozoological or zoomythological in nature. And it was at one such event (but, sadly, I can't remember where or when it was now, as we visited so many, so often, back then) where I saw the very distinctive, eyecatching wooden statuette that is the subject of this present ShukerNature blog article (and is depicted here in a series of photographs showing it from various sides and angles). What I do remember, however, is that when I asked its vendor about its origin, all that he knew was that it was African and had "probably" come from somewhere in West Africa.

More photos of my ambiguous animal statuette – please click to enlarge (© Dr Karl Shuker)

More photos of my ambiguous animal statuette – please click to enlarge (© Dr Karl Shuker)Approximately 9 in long and surprisingly heavy for its size, this enigmatic object was carved out of wood, had been stained a deep cherry-red shade, was very smooth to the touch and quite shiny (especially on the upper right flank, which was a little worn with the colour of its spotting there almost worn off), and was liberally patterned all over its body (including its underparts), limbs, tail, neck, and face with small, simple black spots (like those of a cheetah, as opposed to being arranged in rosettes like a leopard's). There was some slight damage to the right shoulder, and a superficial crack line lower down across that same limb.

The gaping mouth of the creature represented by this statuette possessed a pair of upper and lower canine teeth seemingly made from the cut-off ends of porcupine quills or some such other spiny items, but instead of being inserted vertically, they had been angled so as to project forward. Coupled with the beast's very large mouth (but most especially its extremely big, broad lower jaw), this made these teeth look rather like those of a hippopotamus.

Close-up, front views of my mystifying hipp0-cat – please click to enlarge (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Close-up, front views of my mystifying hipp0-cat – please click to enlarge (© Dr Karl Shuker)Conversely, everything else about the creature was decidedly feline – its face (particularly its whiskers and triangular nose), the overall shape, proportions, pose, and poise of its body and limbs, its long tail with a very leonine tuft of black hair at its tip, its large clawed paws. Indeed, when I first saw it, I initially assumed that it was simply either an imaginative/stylised or else a rather crude/inaccurate portrayal of a leopard. But the more closely I examined it, the more I realised that both of these options were gross simplifications. In reality, it was a very skilfully made statuette, exhibiting all manner of nuances, from the discrete nature of every claw on its paws, and the vertical lines on its neck that in a living animal of this shape and size would indeed arise (constituting skin/muscle creases) when its head reared forward with mouth open wide in a roar or snarl of rage (the pose in which this statuette's creature had been carved), to the unexpected lateral striping rising up on each side of its body from its ventral surface (not what one would expect to see if the creature were meant to be a leopard), and the well-shaped, naturally-proportioned, powerful musculature of its body.

But what creature was it meant to be? It was much too burly and sturdy to be a leopard, and its lateral striping also argued against this identity, as did its leonine tail tuft. Yet its lack of a mane (the flat vertical neck lines offered no suggestion that they represented a mane), and its polka-dot, cheetah-like spotting that profusely patterned its entire form argued against its being a lion either (and even in rare cases of lionesses that have retained into adulthood a degree of spotting, the spotting in question takes the appearance of rosettes, like leopards, not dots as in cheetahs). Moreover, apart from its single shared feature of simple spotting, it bore no resemblance whatsoever to a cheetah.

Spotted hyaena (© AindriúH/Wikipedia CC BY 2.0 licence)

Spotted hyaena (© AindriúH/Wikipedia CC BY 2.0 licence)Could it conceivably be a spotted hyaena Crocuta crocuta? Again, it showed scant – if, indeed, any – similarity to this long-legged, slope-backed, superficially canine creature, other than its spotted coat. And how can we explain its oddly hippo-like lower jaw and teeth orientation? Also, did its staining with red dye have any zoological significance with regard to its creature's morphology and taxonomic identity?

Not surprisingly, faced with such a fascinating array of anomalies and questions associated with them, I was very keen to purchase this statuette, and after a little haggling I succeeded in doing so for £8 – definitely a bargain as far as I was concerned!

Some additional views of my hippo-cat carving – please click to enlarge (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Some additional views of my hippo-cat carving – please click to enlarge (© Dr Karl Shuker)When I arrived back home with it, I spent quite some time that evening online, browsing countless images of African carvings depicting lions, leopards, hyaenas, and hippos, produced by many different cultures and peoples, but I was unable to find any that even remotely resembled my statuette. On the contrary, whereas the latter seemed to be an embodiment of features drawn from all of these creatures, all of the online carvings that I saw were readily recognisable as lions (all with well-defined, furry manes), or leopards, or hippos, etc, with no confusion or overlapping of features between them. I have further browsed online for such carvings on several occasions since then (most recently while writing this present ShukerNature article today), but I have never found one that matches or is even reminiscent of mine.

So, could it be that my mystery statuette was not meant to be a real animal, but is instead merely a composite, uniting the tail and body of a lion with the simple dot-spotting of a cheetah and perhaps the face of a leopard, together with the mouth and teeth of a hippo, for instance, plus some attractive if wholly invented side striping and red body dye added by the sculptor just for good measure? This seems the most parsimonious, conservative explanation. Or might it actually be a representation of some mythical beast from the local folklore of wherever it was made? Needless to say, my quest for answers to this animal's identity has not been assisted by the lack of any precise provenance for this object – after all, West Africa (and only "probably" at that!) is a huge area containing numerous native peoples, and limitless versions and variations of traditional native lore.

Possible appearance of the vassoko or mountain tiger (© Tim Morris)

Possible appearance of the vassoko or mountain tiger (© Tim Morris)Or is it just conceivable that what I purchased on that long-bygone day is a portrayal of a bona fide cryptid? Well worth recalling here is that one of central-western Africa's most notable mystery beasts is the so-called mountain tiger or vassoko – an extremely large, ferocious crypto-felid said to be red in colour but also striped, and possessing a huge mouth containing very large, protruding teeth said to resemble the fangs of the officially extinct sabre-toothed cats or machairodontids. True, it is also said variously to be tailless or to possess only the shortest of tails, as opposed to a long, conspicuous, tufted tail of the kind sported by the creature represented by my carving. But this discrepancy might simply be a mistake on the part of the sculptor, who may not have based the creature's appearance on any firsthand sighting but only upon anecdotal reports that had potentially been confused, or were contradictory, or had been elaborated upon by their tellers.

When I posted some photos of this perplexing carving on Facebook earlier today, some viewers commented that it combined not only feline and hippopotamine (did I just invent a new word there??) similarities but also ursine ones. Might it therefore even be a representation of that most classic of all African cryptozoological composites, the legendary Nandi bear itself? True, although the latter has been likened to a wide range of different animals, including hyaenas, baboons, bears, honey badgers, even aardvarks and the supposedly extinct chalicotheres, it has not usually been compared with a felid form. Then again, in his seminal book On the Track of Unknown Animals (1958), Dr Bernard Heuvelmans did liken the Nandi bear to Proteus – an early marine deity in Greek mythology able to transform himself into a wide range of different creatures – on account of the inordinate diversity of morphological descriptions filed for this cryptid by eyewitnesses. So perhaps there is a feline component to the Nandi bear composite too. Who can say?

An African chalicothere (also featuring a cameo from one of my favourite birds, the

hoopoe

) (© Hodari Nundu)

An African chalicothere (also featuring a cameo from one of my favourite birds, the

hoopoe

) (© Hodari Nundu)Or, returning full circle in my analysing of this bewildering beast's possible identity, could it simply be that its sculptor was in a playful, light-hearted mood when he was creating it, and so decided not to produce just another standard carving of some very familiar animal but rather a very striking, wholly original entity spawned by the fruitful union of his imagination and crafting skills – ultimately yielding a cherry-coloured conundrum, a veritable hippo-cat in fact, with which to baffle and delight in equal measure whoever saw it and subsequently purchased it?

After all, it's not as if cherry-coloured mystery cats are unprecedented in the annals of chicanery. Quoting from the North America-themed chapter in my very first book, Mystery Cats of the World (1989):

No chapter on North American feline mysteries and marvels would be complete without a mention of the celebrated cherry-coloured cat exhibited by that famed American showman Phineas Barnum. After having paid their money to see this wonderful animal, a few of its visitors later protested to Barnum that they had been both surprised and disappointed to discover that it was nothing more than an ordinary black cat. Barnum was quite unmoved by their remonstrance, for, as he reminded them, he had promised them a cherry-coloured cat and, after all, some cherries are black!

There's a lesson for cryptozoology in there somewhere.

Indeed there is!

Scale of my bemusing feline figurine – please click to enlarge (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Scale of my bemusing feline figurine – please click to enlarge (© Dr Karl Shuker)For the most comprehensive modern-day documentation of the Nandi bear controversy, and also various reports of the vassoko or mountain tiger, please check out my new mega-book, Still In Search Of Prehistoric Survivors .

Published on December 17, 2016 13:52

December 12, 2016

A SCALY STATUETTE OF THE MOKELE-MBEMBE?

Carved wooden statuette of a scaly sauropod-like creature and a smaller short-necked mystery beast; probably of West African origin, currently housed at Glencomeragh House, Ireland(© Brother Richard Hendrick)

Carved wooden statuette of a scaly sauropod-like creature and a smaller short-necked mystery beast; probably of West African origin, currently housed at Glencomeragh House, Ireland(© Brother Richard Hendrick)On 7 April 2013, Brother Richard Hendrick, a Capuchin Franciscan Friar (Monk) of the Irish Province who has long been interested in cryptozoology, posted on my 'Journal of Cryptozoology' Facebook group's page a colour photograph that he had snapped a few days earlier, depicting a very eyecatching wooden statuette, and which I have included above by kind permission of Brother Richard.

He also included the following details about it:

Found this African carving in a collection held by the Rosminian Missionary Fathers in Glencomeragh House, Clonmel [in County Tipperary] Ireland. No provenance or date other than sometime this century probably from west Africa. Intriguing?

The mokele-mbembe rendered as a sauropod, by David Miller under the direction of Prof Roy P Mackal (© Prof. Roy P. Mackal)

The mokele-mbembe rendered as a sauropod, by David Miller under the direction of Prof Roy P Mackal (© Prof. Roy P. Mackal)After a few replies from others in this FB group were posted in response to his photo and comment, including one from American crypto-author Matt Bille saying that it looked to him like a modern creation, possibly inspired by western interest in the mokele-mbembe (rather than an example of traditional native artwork), Brother Richard responded as follows:

I'm afraid I know very little more than I mentioned above. The Rosminian Fathers are a missionary order and worked for many years in Africa. Many of the Irish fathers brought back souvenirs of their time there on their return to Ireland. I was merely visiting the house on retreat myself and spotted it sitting dusty and forgotten amongst many other carvings. I would guess it has been there since at least the 1950s as no one currently living in the house seemed to know anything about it and didn't see it as anything extraordinary. It does have a "modern" feel but I felt it was worth sharing.

(Judging from his comment that he felt that this carving had probably been at Glencomeragh House since at least the 1950s, his previous comment that it probably dated from "sometime this century" was no doubt simply a slip of the pen, having forgotten momentarily that this is now the 21st Century, not the 20th.)

Close-up of this intriguing 'scaly sauropod' statuette (© Brother Richard Hendrick)

Close-up of this intriguing 'scaly sauropod' statuette (© Brother Richard Hendrick)Brother Richard's final posts concerning the carving read as follows:

I have to say I was more intrigued by the second creature? Not sure if it represents a "baby" or another species. I guess at the very least it demonstrates the creature being present in a "culture" even if it was introduced as an idea by those seeking it.

Not sure if it is in a fighting / mating / feeding pose with the larger creature. They both appear to have the same tail, scales and cloacal opening though. A puzzle to add to the connundrum of the whole piece! Never seen anything like it before though!

When I contacted him directly concerning this carving, I learnt that it was roughly 6 in tall, was quite heavy, seemed to have been carved from a single piece of wood, and although he had examined it rather thoroughly he did not see any inscriptions or dates on it.

There is no question that the larger of the two animals in this carving closely resembles a sauropod dinosaur in body shape. However, it also sports certain highly unusual features for any such identity. Most obvious of these is its array of extremely large, almost pangolin-like overlapping scales, which are absent only from its face, feet, and, most noticeably, the entire extent of its long tail, and which have not been reported by mokele-mbembe eyewitnesses in the Congo (though crocodile-like scales have been claimed by the Baka pygmies for their Cameroon version, the li'lela-bembe). Nor has the large, even more intriguing – and very odd - rayed fin-like structure visible on the underside of its tail's basal portion, which Brother Richard suggested may be a cloacal opening. And its long pointed teeth are not what one would expect from a herbivore, though these may simply be non-specific, stylised representations.

Pangolin (public domain)

Pangolin (public domain)As for the carving's second, smaller animal, standing upright on its hind legs, possibly supported somewhat by its tail, but also resting directly upon the sauropod-like beast's rear body portion, this does not resemble any creature known to me and is something of a paradox. For whereas it sports exactly the same type of body scales as the 'sauropod', and the same kind of tail too, even bearing an identical rayed fin on its tail's basal underside, the body scaling is absent from its lower limbs, it totally lacks the long neck of the 'sauropod', and its face and jaws do not match those of the latter beast either.

Is this small animal meant to represent a young version of the 'sauropod', I wonder? The presence of the same type of scales and in particular the very distinctive underside tail fin (which is unlike anything that I know of in vertebrates present or past), would certainly support such a possibility. Yet its virtually non-existent neck argues in an equally persuasive manner against this option. Even the pose in which the 'sauropod' has been depicted in relation to the small animal is somewhat ambiguous, as recognised by Brother Richard too, and could be construed equally as one of anger toward a potential attacker or as one of response (feeding?) toward its own offspring.

Close-up of the smaller animal in this carving (© Brother Richard Hendrick)

Close-up of the smaller animal in this carving (© Brother Richard Hendrick)British mystery beast researcher Penny Odell made a very interesting, original contribution to the series of comments posted beneath Brother Richard's photo of the carving that may explain the small creature's contradictory form:

I think it is supposed to be the same species. However the artist only had a certain space and size of wood and ability to carve with. Had the smaller animal been given a longer neck it would have changed the carving making it harder to carve into the space[;] therefore the artist made the smaller animal with a shorter neck for convenience.

With virtually no historical information concerning this fascinating artefact available, there is little more that can be said about it. Despite being for many years a keen visitor to antique/collector/ethnic-craft fairs and shops, and an equally avid online browser relating to such areas of interest, I have never encountered anything even similar, let alone identical, to this carving before. And if it does date back to at least the 1950s, this long precedes the Mackal mokele-mbembe expeditions from the early 1980s that incited the continuing modern-day wave of interest in the latter Congolese cryptid, thereby offering support for believing that this carving's creation was not sparked by any Western interest in such a creature after all. Yet if it is a traditional native depiction of a mokele-mbembe or comparable cryptid, how can the scaling, the tail fin, and the short-necked smaller beast be explained?

Another sauropod-inspired representation of the mokele-mbembe (© Richard Svensson)

Another sauropod-inspired representation of the mokele-mbembe (© Richard Svensson)My sincere thanks to Brother Richard for so kindly making available to me his photograph of this enigmatic, hitherto-unpublicised statuette and his information concerning it.

This ShukerNature blog article is excerpted from my newly-published mega-book, Still In Search Of Prehistoric Survivors .

Published on December 12, 2016 05:56

December 9, 2016

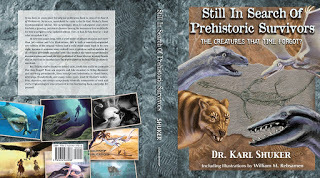

STILL IN SEARCH OF PREHISTORIC SURVIVORS - CHOSEN AS THE BEST CRYPTOZOOLOGY BOOK OF 2016

Just two days after I received from Loren Coleman and the International Cryptozoology Museum the prestigious Golden Yeti Award as Cryptozoologist of the Year 2016 – a massive honour recognised internationally as the veritable Oscar of Cryptozoology – I was delighted and awed to discover on my birthday yesterday that in his always much-anticipated annual listing of the year's best cryptozoology books Loren has chosen my newest book, Still In Search Of Prehistoric Survivors: The Creatures That Time Forgot? , as THE Best Cryptozoology Book of 2016 !!

Not only that, but also included in his Top Ten Cryptozoology Books of 2016 listing (click here to view it on Loren's CryptoZooNews website) is my earlier 2016 book, Here's Nessie! A Monstrous Compendium From Loch Ness . Thank you so much, Loren, for bestowing such praise and honour upon my books - I am truly grateful, and very greatly honoured. Moreover, I'd like to take this opportunity to offer my thanks too to all of the numerous correspondents, artists, and crypto-colleagues globally whose much-valued contributions to these books of mine have helped them achieve such success.

How I wish that my dear mother Mary Shuker, who initiated my life-long passion for cryptozoology (click here for details), could have seen all of this – she would have been so proud of her lad, as she always fondly called me and whom she loved so much. God bless you Mom, and thank you again most sincerely Loren. This is what has always encouraged me in the researching and writing of my books and articles, and made it all so worthwhile for me – namely, to learn via such recognition as this that my work is valued so much by, and gives so much pleasure to, readers and fellow researchers/writers alike. What more can any author ask for?

Published on December 09, 2016 18:02

December 8, 2016

A GOLDEN YETI FOR MY BIRTHDAY!! - CRYPTOZOOLOGIST OF THE YEAR 2016

Today is my birthday – as for which one, let's just say that I've reached an age where it's probably best to draw a discreet veil over such questions, lol – and down through the years on this day I've received many wonderful items, but this is definitely the first time that I've ever received a Golden Yeti!

Two days ago, my birthday arrived early, as it were, when I was delighted, amazed, and very honoured by an official announcement on Loren Coleman's CryptoZooNews website that he and the International Cryptozoology Museum had awarded me their prestigious Golden Yeti Award as Cryptozoologist of the Year 2016. And yes, there is indeed a Golden Yeti statuette accompanying the award, equally as coveted among cryptozoologists as the Academy Award or Oscar is among movie actors and the Grammy is among musicians, and which will definitely occupy a very special place in my study.

So I wish to take this opportunity to thank Loren and the ICM most sincerely for bestowing such a great honour upon me in recognition of my contributions to cryptozoology.

Mom and I at the Grand Canyon, Arizona, in 2004 (© Dr Karl Shuker)