Karl Shuker's Blog, page 26

June 30, 2017

GREEN GROW THE TIGERS, O – AT LEAST IN VIETNAM?

Here's one I made earlier - a green tiger created by me via computerised photo-manipulation (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Here's one I made earlier - a green tiger created by me via computerised photo-manipulation (© Dr Karl Shuker)Quoting from a previous ShukerNature blog article of mine (click here to read it):

In various of my books, articles, and ShukerNature posts concerning cryptozoological and mythological big cats, I have documented lions of many different hues and shades, including black lions (click here , here , and here ), white lions (click here ), grey lions, red lions, golden lions, and even an alleged green lion (click here ) – but never a blue lion. Blue tigers, yes (click here ) – blue lions, no. Until now, that is.

I then went on to reveal that I had recently discovered some African and Asian legends relating to blue lions that I had never known about before, and I devoted the rest of that blog article to them.

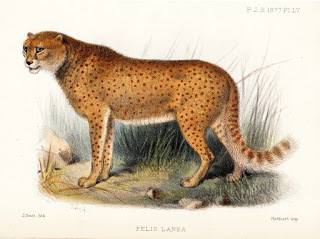

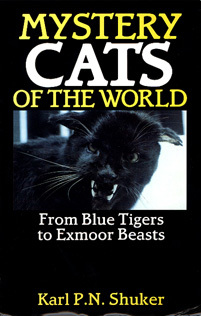

But why am I reiterating all of this here? The reason is that I now find myself in a comparable situation with tigers. Over the years, I have documented tigers in virtually every conceivable shade and stripe version – blue tigers as already noted, plus black tigers (click here ), white tigers ( here ), golden tigers ( here ), snow tigers ( here ), red tigers, brown tigers, double-striped tigers, and even stripeless tigers (all of which are also collectively documented in my books Mystery Cats of the World and Cats of Magic, Mythology, and Mystery ) – except for one. I had never encountered a report or sighting of a green tiger – until now, that is.

In an earlier ShukerNature article, I mentioned how correspondent James Nicholls from Perth, Australia, had sent me a fascinating email on 27 June 2017 concerning a hitherto-obscure published account from 1821 concerning giant oil-drinking spiders reputedly inhabiting two of Europe's very notable edifices of worship, an account that almost certainly inspired Bram Stoker to insert a short, comparable account in his classic Gothic novel Dracula(1897). Click here to read on ShukerNature my investigation of this fascinating subject. However, that wasn't the only remarkable piece of information contained in James's email to me.

It also included a link to a thoroughly extraordinary account on the website Reddit, which had been posted on Christmas Day 2016 by someone with the username AnathemaMaranatha and seemingly of American nationality (judging from their style of grammar and spelling, and various other Reddit posts by them), and consisted of their supposed first-hand eyewitness description of a truly unique mystery cat. It reads as follows: (Or click here to view it in its original format on Reddit.)

Okay. I saw a green tiger. I wasn't alone.

We were out towards the Cambodian border in summer of 1969, an American light infantry company of about 100 or so guys. We were operating in flatlands, thick jungle, along a river. (Saigon River? Not sure.) Bright, sunny day.

We were proceeding single file when point platoon came to a stop, there was some yelling (we were stealthy - yelling is bad) from the point, then point platoon radioed for the Command Post (CP - the company commander and his people) to come up to point.

When we got there, we found the point team glaring at each other - some kind of tussle. Point and drag were standing in the machine gunner's line of fire glaring at him. The machine gunner had wanted to shoot. Point and drag stopped him. He didn't like that.

The object of discussion was across a jungle opening maybe 15 meters away, just peeking at us over the elephant grass. It was a bigtiger - biggest I've ever seen, Frank Frazetta-style big, but without the lady.

Here's the insane part. The tiger was white where a tiger is white and black where a tiger is black, but all the orange parts were a pale green. We all saw it, maybe twenty grunts and me. The machine gunner was arguing that we have to shoot it, because otherwise no one would believe it. He had a point.

But the rest of us were just awestruck. I mean, it might as well have been an archangel, wings halo and all. I felt an impulse to kneel. I don't think I was alone.

The tiger stood there checking us out for maybe 15 minutes, not worried, not angry, just a curious cat. Then he turned and disappeared.

Don't believe me? That's okay. I don't believe it myself. I mean WTF was that? Hallucinogenic elephant grass? Some trick of the light? The tiger walked through some kind of green pollen just before we saw it? No freakin' idea.

There it is, OP. I don't believe it, and I sawit. Or hallucinated it. Me and all my blues. Make of it what you will. I'm done.

In fact, this person did make a few additional, minor comments in reply to various responses from other Reddit readers, of which the following one is well worth recording here:

I apologize for not making clear that the tiger was scaring the shit out of all us. He did NOT look sick or malnourished. He looked like he could be right in the middle of all of us in no time flat. He thought so, too. Didn't seem the least bit scared of us.

And I guess he wasn't hungry.

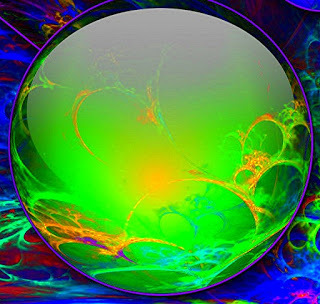

Another of my computer-generated green tigers (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Another of my computer-generated green tigers (© Dr Karl Shuker)Not surprisingly, faced with an account from someone claiming to have encountered a green tiger, my initial reaction was to assume that it was just a spoof, a joke, not to be taken seriously. But then I decided to investigate the credentials of the person who had posted it, especially as their account did sound as if it had been written by someone familiar with military action in Vietnam, and I was very intrigued to discover that they had written a number of other, much more mainstream and very detailed accounts on Reddit concerning their alleged time and military service there during the Vietnam War that all seemed entirely authentic (e.g. click here ), and had been well-received by Vietnam veterans who would surely spot and soon expose any imposter. Consequently, it seems both reasonable and parsimonious to assume that this person's Vietnam-related testimony is indeed genuine.

But a green tiger? Really? I noticed that the green tiger account had attracted an interesting response (by someone with the unfortunate username eggshitter):

It was a bright sunny day right? Is there any chance that there was some murky green pool that reflected the light on to the tiger? Maybe he had just been rolling around in the grass?

Other, later posters made similar comments. They reminded me of a suggestion that has been put forward in the past concerning the blue tigers of Fujian, China – namely, that perhaps their distinctive fur colouration was simply due to their having rolled in bluish-coloured mud. However, as I have pointed out when responding to this suggestion, if that were true the entire tiger would look blue, whereas eyewitnesses have specifically mentioned seeing their black stripes and pale underparts, which of course would have been obscured if they had rolled in mud. The same logic, therefore, can be applied to the green tiger had it merely been rolling around in grass, or even, perhaps, in an alga-choked jungle pool.

Conversely, an optical illusion induced by reflected light is certainly possible. Yet bearing in mind the substantial length of time of the observation (15 minutes), and which was made by several different people simultaneously rather than just a single observer, this might initially seem somewhat improbable too.

On 19 November 2012, however, after having blogged about an alleged green lion seen in Uganda, East Africa (click here ), I had received a fascinating response from John Valentini Jr (a Cryptomundo website reader who had seen a link to my article posted there by fellow cryptozoologist Nick Redfern), and which is also directly relevant to this present green tiger conundrum. So here is the summary of John's response that I added as a comment below my green lion blog article:

One day, while visiting a local zoo, John photographed a lioness, of totally normal colouration, but when he received his negatives and prints back from the developers (i.e. back in the days before digital photography), he was very surprised to discover that in them the lioness was green! She had been walking through an expanse of grass with her body held low when he had photographed her, and at the precise angle that John was photographing her the green light reflecting from the grass had made her look green. (Some grass, noted John, can be around 18-26% reflective.) Having to concentrate keeping his camera focused upon her through only a small viewfinder and thick glass, however, John hadn't noticed this optical effect himself - not until the negatives and prints had subsequently revealed it. Consequently, John speculates that perhaps, if viewed at precisely the correct angle, a similar effect could occur with a lion observed in the wild in decent light conditions but with plenty of green foliage around it, and that this may explain the Ugandan prospector's claimed sighting of a green lion.

Needless to say, I am delighted that John documented his extraordinary photographic experience on Cryptomundo in response to the link to this ShukerNature article of mine, as it may indeed offer a very plausible, rational explanation for the alleged green lion of Uganda - but one so remarkable that I would never even have thought of it, had John not posted it - so many thanks, John, once again!

Yes indeed, and it may also offer an equally plausible, rational explanation for the alleged green tiger of Vietnam – always assuming, of course, that the report is genuine. And there, at least for now, is where this most intriguing case rests, currently unproven but undeniably curious.

Of course, despite having bewailed the fact that I had never previously encountered anything about green tigers, there is one undoubted exception…of sorts. And that exception, as cartoon and super-hero fans everywhere are no doubt only too ready and waiting to remind me, is of course a certain golden-striped green tiger named Cringer – the very large but also very cowardly feline companion of Prince Adam, aka He-Man, in the very popular Masters of the Universe cartoon TV series (1983-1985) produced by Filmation (and also in the later movie starring Dolph Lundgren). Of course, when He-Man points his sword towards Cringer and fires an energy beam at him, Cringer redeems himself by transforming (albeit reluctantly) into his even bigger and now totally fearless, ferocious alter-ego felid called Battle Cat.

Two views of my original 1983 model of Cringer/Battle Cat (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Two views of my original 1983 model of Cringer/Battle Cat (© Dr Karl Shuker)As far as I am aware, however, neither as Cringer nor as Battle Cat has this green-furred tigerine celebrity ever paid a visit to Vietnam…

Finally: just in case anyone is confused by this ShukerNature article's main title, it is a play on the title of a traditional English folk song, 'Green Grow The Rushes, O', which was also often used with children as a counting song (and should not be confused, incidentally, with the similarly-titled song 'Green Grow The Rushes' by Robert Burns).

I am extremely grateful to James Nicholls for very kindly bringing this apparent eyewitness report of a green tiger to my attention.

My two books on mystery cats (© Dr Karl Shuker)

My two books on mystery cats (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Published on June 30, 2017 11:25

June 28, 2017

DRACULA, VAN HELSING, AND GIANT SPIDERS IN THE CATHEDRAL

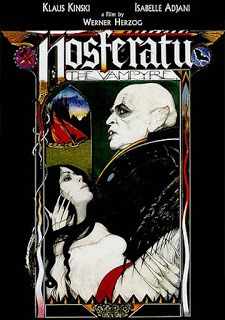

Official movie poster for the 1979 horror film Nosferatu the Vampyre (© Werner Herzog Filmproduktion/20th Century Fox – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis only)

Official movie poster for the 1979 horror film Nosferatu the Vampyre (© Werner Herzog Filmproduktion/20th Century Fox – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis only)A few weeks ago, I finally found time to watch a horror film that I had long been planning to see. Directed by Werner Herzog and starring Klaus Kinski in spellbinding form as the title character, the film in question was Nosferatu the Vampyre, the very stylish 1979 West German art-house remake of the cult 1922 German silent movie Nosferatu(starring Max Schreck), which in turn was loosely based upon Bram Stoker's classic epistolary vampire novel Dracula.

Little did I think while viewing it that only a short time later I would be investigating a fascinating but hitherto-obscure cryptozoological conundrum tucked away within the pages of the selfsame famous novel that had inspired this film – but that is precisely what happened, providing further confirmation for what I have always known, especially when dealing with mystery animals. Always expect the unexpected, and you will never be disappointed.

So here is that recent investigation of mine, presented here as a ShukerNature exclusive – the ever-curious case of Dracula, Van Helsing, and Giant Spiders in the Cathedral.

Bram Stoker in 1906 (public domain)

Bram Stoker in 1906 (public domain)Many years ago, while reading Stoker's Dracula, which was originally published in 1897, I was intrigued by the following short but memorable aside spoken by the eminent vampire hunter Prof. Abraham Van Helsing to his former student Dr John Seward:

Can you tell me why, when other spiders die small and soon, that one great spider lived for centuries in the tower of the old Spanish church and grew and grew, till, on descending, he could drink the oil of all the church lamps?

At the time of reading it, however, I simply assumed that this extraordinary statement was nothing more than the product of Stoker's very fertile, and febrile, imagination. Consequently, I swiftly dismissed it from my mind, never considering for a moment that it may actually have been inspired by reality.

And then, just a few days ago, I received a fascinating email from a correspondent that has incited me to revisit this brief passage from Dracula and reassess it in a much more enlightened manner.

Hugh Jackman as Van Helsing in the 2004 Universal Pictures movie Van Helsing(© Universal Pictures, included here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis only)

Hugh Jackman as Van Helsing in the 2004 Universal Pictures movie Van Helsing(© Universal Pictures, included here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis only)Received by me on 27 June 2017, the illuminating email in question was from James Nicholls of Perth, Australia, who very kindly informed me that in 1821 two separate periodicals, the Edinburgh Magazine and Literary Miscellany (vol. 88, July-December, p. 268) and The Atheneum; or, Spirit of the English Magazines (vol. 9, April-October, p. 485), had published the following short but fascinating account (referred to hereafter in this ShukerNature blog article of mine as the 1821 account), concerning giant oil-drinking spiders lurking amid the shadows of two major European edifices of religious worship:

The sexton of the church of St Eustace, at Paris, amazed to find frequently a particular lamp extinct early, and yet the oil consumed only, sat up several nights to perceive the cause. At length he discovered that a spider of surprising size came down the cord to drink the oil. A still more extraordinary instance of the same kind occurred during the year 1751, in the Cathedral of Milan. A vast spider was observed there, which fed on the oil of the lamps. M. Morland, of the Academy of Sciences, has described this spider, and furnished a drawing of it. It weighed four pounds, and was sent to the Emperor of Austria, and is now in the Imperial Museum at Vienna.

Needless to say, reading through this remarkable account, one is irresistibly reminded of Van Helsing's comment as penned by Stoker in Dracula – so much so, in fact, that surely there can be little if any doubt that this was indeed Stoker's source of inspiration for that comment, especially as this account was published 76 years before Stoker's novel first appeared in print.

Presumably, Stoker either misremembered the locations given for these stupendous spiders in the account, or he purposefully changed them in order to make it look as if Van Helsing had only retained a hazy, incompletely accurate memory of the account. Both of these possibilities could satisfactorily explain why he cited a Spanish church rather than either the French one or Milan Cathedral as named in the account.

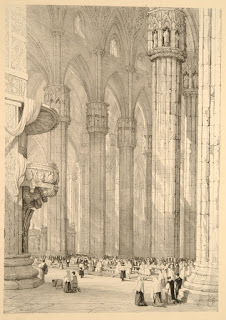

Exquisite 19th-Century illustration of Milan Cathedral, capturing very effectively its immense size – big enough, surely, to conceal even the most monstrous of spiders amid the shadows embracing its upper regions during the hours of daylight? (public domain)

Exquisite 19th-Century illustration of Milan Cathedral, capturing very effectively its immense size – big enough, surely, to conceal even the most monstrous of spiders amid the shadows embracing its upper regions during the hours of daylight? (public domain)But might there be any factual substance to the above account, or was it too merely a work of fiction? Initially, the concept of any kind of oil-drinking spider, irrespective of body size considerations for the time being, seemed ludicrous. After all, kerosene would surely be toxic to such creatures. But when I began to research the account, I began to wonder.

For I discovered that back when it was published, during the early 1800s, and especially during the even earlier time period named by it during which the giant cathedral spider of Milan was reportedly discovered, i.e. during the early 1750s, the oil commonly used in lamps was derived from whale blubber or rendered animal fat, and therefore could conceivably be nutritious for spiders.

Moreover, spiders typically imbibe their sustenance in liquid form anyway; on account of the narrowness of their gut, they cannot digest solid food, so after immobilising or killing their prey with injected venom or enshrouding silk, they pump digestive enzymes into it from their midgut, then suck the prey's now-liquefied tissues into their gut. So the oil-drinking proclivity attributed to these great spiders is not as implausible as one might otherwise assume.

My book

Mirabilis

(© Dr Karl Shuker)

My book

Mirabilis

(© Dr Karl Shuker)But what about their prodigious magnitude? My book Mirabilis; A Carnival of Cryptozoology and Unnatural History (2013) contains an exceedingly comprehensive chapter documenting a varied array of giant spider reports originating from all over the world. Within that chapter (as well as within a ShukerNature blog article on giant spiders excerpted and expanded from it - click here ), I discussed as follows the crucial physiological flaw inherent in all speculation concerning the plausibility (or otherwise) of such creatures:

The fundamental problem when considering giant spiders is not one of zoogeography but rather one of physiology. Their tracheal respiratory system (consisting of a network of minute tubes carrying oxygen to every cell in the body) prevents insects from attaining huge sizes in the modern world, because the tracheae could not transport oxygen efficiently enough inside insects of giant stature. During the late Carboniferous and early Permian Periods, 300 million years ago, huge dragonflies existed, but back in those primeval ages the atmosphere's oxygen level was far greater than it is today, thereby compensating for the tracheal system's inefficiency.

Some of the largest known spiders also utilise a tracheal respiratory system, whereas smaller spiders employ flattened organs of passive respiration called book lungs. Yet neither system is sufficiently competent to enable spiders to attain enormous sizes, based upon current knowledge at least. So if a giant spider does thrive…it must have evolved a radically different, much more advanced respiratory system, not just a greatly enlarged body.

Also, giant spiders are very much the embodiment of primeval bogey beasts, created both consciously, by parents to playfully scare their children and to make them aware of the potential danger posed by various real but highly venomous species, and unconsciously, by the human imagination working overtime in relation to creatures whose potential danger is buried very deep within the fundamental human psyche. Surely it can be no coincidence that giant spiders, almost invariably of evil intent, appear in the traditional folklore and mythology of very different cultures all around the world.

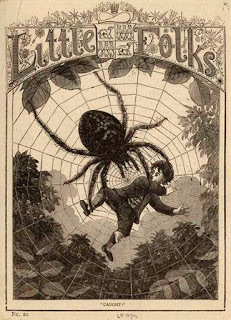

Keep away from spiders, kids, or this might happen to you! (public domain)

Keep away from spiders, kids, or this might happen to you! (public domain)Then again, outrageous journalistic hokum was extremely common in the West during much of the 19th Century, i.e. when the 1821 account was published, so perhaps that is all that it ever was, with no basis whatsoever in fact. After all, elsewhere on ShukerNature I have already documented such arachnological absurdities as the deadly giant siren-singing spider of Paris, France (click here ), and the giant flying tomb spider of Rome, Italy (click here ), both of which debuted in highly-suspect 19th-Century newspaper reports.

Since receiving the 1821 account from James Nicholls, I have conducted some appreciable online research in a quest for supplementary details appertaining to its contents, and have uncovered a few additional coverages of it, some back in the 1820s and others from modern times. However, all of them confine themselves almost exclusively to the details already provided in the Edinburgh Magazine and Literary Miscellany and The Atheneum.

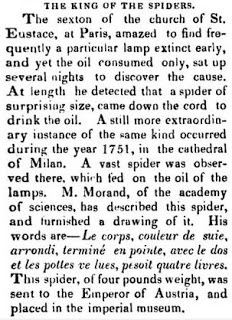

Indeed, the most informative version that I have accessed so far, entitled 'The King of the Spiders', remains the one that appeared in The Atheneum, so here it is in full:

'The King of the Spiders' article from Vol. 9 (April-October 1821) of The Atheneum; or, Spirit of the English Magazines (public domain)

'The King of the Spiders' article from Vol. 9 (April-October 1821) of The Atheneum; or, Spirit of the English Magazines (public domain)As can be seen, in addition to the standard details present in other versions, it also actually contains Morand's own verbal description (in French) of the giant Milan Cathedral spider. This translates into English as:

The body, the colour of soot, rounded, terminated in a point, with the back and the limbs hairy, weighed four pounds.

Two of the most notable 20th-Century publications to include mention of it are English spider authority W.S. Bristowe's A Book of Spiders (1947), and eminent British zoologist Prof. John L. Cloudsley-Thompson's authoritative work Spiders, Scorpions, Centipedes and Mites: The Ecology and Natural History of Woodlice, Myriapods, and Arachnids (1958). Worth noting is Bristowe's line of delightfully tongue-in-cheek speculation that he pursued in his coverage of the events detailed in the 1821 account:

I suspect the sexton [of St Eustace's Church in Paris] was under grave suspicion of borrowing the oil himself until he reported seeing [the giant spider stealing it].

Although he never stated it overtly, to my mind Bristowe's wording indicates that he entertained the possibility that the sexton had invented the entire giant spider story in order to conceal the fact that it was he who was stealing the oil. Who knows – perhaps the sexton had been aware of the report of the great spider from Milan Cathedral, and so was inspired by it to create a version of his own in order to hide his nefarious involvement in the oil's disappearance in his own place of worship.

Retitled as Spiders, reprint of W.S. Bristowe's A Book of Spiders (© King Penguin Books, reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis only)

Retitled as Spiders, reprint of W.S. Bristowe's A Book of Spiders (© King Penguin Books, reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis only)Sadly, the 1821 account tantalises rather than teaches its readers, by offering more questions than answers. Who, for instance, was Morland (or Morand, as so named in The Atheneum's version of events), who produced a drawing of the great spider of Milan Cathedral from 1751, and where is that drawing today? Does it still survive? I wonder if Morland (or Morand) could have been the English animal artist George Morland (1763-1804). And which museum is being referred to in the 1821 account as 'the Imperial Museum at Vienna'? However, it may well be Austria's Imperial Treasury Museum, which is housed at the Hofburg Palace in Vienna, and contains many secular and ecclesiastical items spanning more than a millennium in European history.

In any event, I deem it highly unlikely that a preserved 4-lb spider exists in any museum collection within Austria – after all, as Bristowe pithily observed in his own coverage, it would be as big as a pekingese dog! Having said that, I would love to be proved wrong, so if anyone reading this article has knowledge of where such a specimen might be held today if it ever did once exist, I would greatly welcome details.

Nevertheless, having reported two separate specimens of giant spider means that the 1821 account is guaranteed to be of very appreciable interest and importance to cryptid seekers anyway. This makes it all the more surprising that (at least as far as I'm aware) its documentation in this present ShukerNature blog article of mine is the very first time that it has ever appeared in any strictly cryptozoological context.

Face to face – a (very) close encounter of the arachnid kind! (Vicky Nunn/public domain)

Face to face – a (very) close encounter of the arachnid kind! (Vicky Nunn/public domain)Now that it has very belatedly done so, however, let us hope that it elicits further details concerning those spiders of stature documented within it, and perhaps concerning additional specimens too.

I wish to offer my most sincere and grateful thanks to James Nicholls for kindly bringing the 1821 account to my attention.

Finally: how could any article inspired by Stoker's Gothic literary masterpiece be considered at an end without having included at least one appearance from a member of the undead fanged fraternity – so here it is:

A vampire from the modern school of bloodsuckers, complete with fashionably-unkempt rock star looks, locks, and designer stubble, but clearly retaining the old school's fangs, ferocity, and mainstream malevolence – not a sparkle, shimmer, or outbreak of whimpering fangless adolescent angst to be seen anywhere here! (© David de la Luz/Wikipedia

CC BY-SA 2.0 licence

)

A vampire from the modern school of bloodsuckers, complete with fashionably-unkempt rock star looks, locks, and designer stubble, but clearly retaining the old school's fangs, ferocity, and mainstream malevolence – not a sparkle, shimmer, or outbreak of whimpering fangless adolescent angst to be seen anywhere here! (© David de la Luz/Wikipedia

CC BY-SA 2.0 licence

)

Published on June 28, 2017 08:20

June 7, 2017

BRIDE OF THE LINDORM

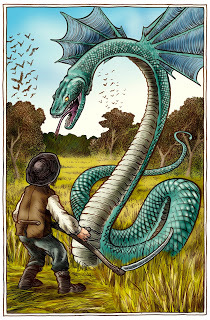

The prince meeting his lindorm brother, from Folk Tales of the World, written by Roger Lancelyn Green, illustrated by Janet and Anne Grahame Johnstone, and published in 1966 by Purnell and Sons Ltd (© Roger Lancelyn Green/ Janet and Anne Grahame Johnstone/Purnell and Sons Ltd – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis only)

The prince meeting his lindorm brother, from Folk Tales of the World, written by Roger Lancelyn Green, illustrated by Janet and Anne Grahame Johnstone, and published in 1966 by Purnell and Sons Ltd (© Roger Lancelyn Green/ Janet and Anne Grahame Johnstone/Purnell and Sons Ltd – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis only)I owe much of my lifelong love of mythology to the wonderful works of Roger Lancelyn Green that my mother Mary Shuker bought for me when I was a child, in which he retold countless famous and little-known myths, legends, folktales, and fables from all around the world. Moreover, it was within these works that I first encountered many enthralling fabulous beasts and other folkloric entities, including the Japanese tanuki, the Mexican kuil kaax (click here for my ShukerNature coverage of this magical woodland spirit), the Australian kurreah (click here ), and – in Green's delightful book Folk Tales of the World, exquisitely illustrated throughout in full colour by Janet and Anne Grahame Johnstone, which I still treasure to this day – the Swedish lindorm.

Lindorms are semi-dragons inasmuch as they occupy an intermediate echelon in the evolution of the dragon from the serpent. Typically (but not invariably) two-legged and wingless, lindorms have greater affinities with the serpents than with the classical dragons (in contrast, wyverns, which are also semi-dragons, possess not only a pair of legs but also a pair of wings, so they are closer to the classical dragons than to the serpents).

A sturdy typical two-limbed lindorm readily demonstrating its semi-dragon status, intermediate between a limbless serpent dragon and a quadrupedal classical dragon (public domain)

A sturdy typical two-limbed lindorm readily demonstrating its semi-dragon status, intermediate between a limbless serpent dragon and a quadrupedal classical dragon (public domain)Incidentally, the term 'lindorm' should not be (but often is) confused with 'lindworm' – which technically should only be applied to wingless four-limbed classical dragons. In heraldry, however, it is commonly applied to lindorms.

Lindorms were commonly met with in churchyards, where they ghoulishly devoured human corpses, and would sometimes invade churches too. They occurred in great numbers amid the mountainous peaks of central Europe - indeed, the elaborate dragon-shaped fountain in Klagenfurt, Austria, was inspired by the discovery in 1335 of a supposed lindorm skull (it later proved to be from a woolly rhinoceros!).

A limbless Swedish lindorm, resembling a gigantic snake (© Richard Svensson)

A limbless Swedish lindorm, resembling a gigantic snake (© Richard Svensson)Their favourite land, however, was Sweden, which contained quite a variety of versions, including legless lindorms and even one that sported a small pair of fore-wings instead of a pair of legs. But most Swedish lindorms were of the typical two-limbed variety. There are many traditional tales from this Scandinavian country concerning these particular semi-dragons, but perhaps the most celebrated example is the one that I shall now retell here.

A rare winged Swedish lindorm (© Richard Svensson)

A rare winged Swedish lindorm (© Richard Svensson)Untold centuries ago, the Swedish monarch's queen lay in her bedchamber, about to give birth to twins - the fulfilment of many years of empty longing for the children that she seemed destined never to conceive. She smiled, as she remembered how, in final desperation, she had consulted a soothsayer who had assured her that in less than a year's time she would be granted two handsome sons - provided that she ate two fresh onions as soon as she returned home to the palace.

The advice seemed quite bizarre, but the queen was so aroused by the chance, however slim, that it offered to her that she made her way back to the palace at once, anxious to seek out the necessary vegetables without delay. Recalling this scene, she also remembered hearing the soothsayer calling after her, but as she had already told her about the onions, the soothsayer's message clearly couldn't have been of much importance, and so the queen hadn't wasted time turning back. Instead, she had continued her journey home, and upon arriving had ordered two crisp, mature onions to be brought to her immediately.

When she received them, the queen was so excited by the promise that these innocuous vegetables held that she ate the first one whole, without even stopping to peel the skins from it. Not surprisingly, however, it tasted quite revolting - and so in spite of her enthusiasm she spent time carefully peeling the second one, stripping away every layer of skin, before finally eating it. Nine months had passed since then, and now, precisely as prophesied by the soothsayer, she was about to bear her greatly-desired children.

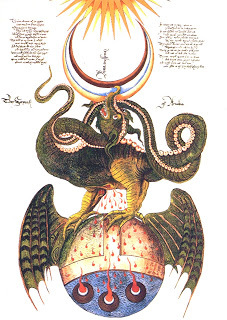

'The Serpent of Arabia' – a lindorm sumptuously depicted in the Ripley Scroll, a 15th-Century alchemical manuscript of emblematic symbolism, and of unknown origin but named after Sir George Ripley, a famous English alchemist (public domain)

'The Serpent of Arabia' – a lindorm sumptuously depicted in the Ripley Scroll, a 15th-Century alchemical manuscript of emblematic symbolism, and of unknown origin but named after Sir George Ripley, a famous English alchemist (public domain)The palace courtiers and staff eagerly clamoured outside the royal bedchamber, awaiting the official announcement of the new princes' births. Suddenly, an ear-splitting scream echoed within the chamber - but it was not the lusty cry of a newborn baby. It was, instead, a shriek of horror - an eldritch wail that leapt unbidden from the throat of the royal midwife when she set eyes upon the queen's firstborn. It was male - but it was not human.

The queen had given birth to a lindorm - a hideous snake-like dragon, whose wingless elongate body thrashed upon the marble floor in innumerable scaly coils, and from whose shoulders sprang a pair of powerful limbs with taloned feet. Deathly pale and so repulsed by the creature that she was unable even to whisper, let alone scream, it was the queen, still in labour with her second child, who leaned down, took the young lindorm in her arms - and hurled it, with all the power that her loathing could summon, through a nearby window, from where the creature plummeted into the dense forest surrounding the palace.

Weakened from the exertion, she sank back upon the bed, and gave birth again - but this time to a perfectly healthy, fresh-faced boy, with golden hair and sparkling blue eyes.

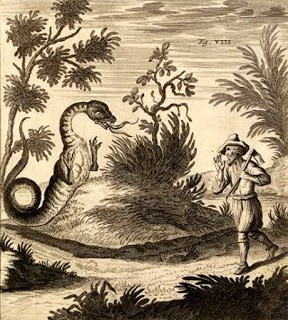

Encountering a traditional two-limbed lindorm in Switzerland, from

Itinera per Helvetiae Alpinas Regiones Facta Annis 1702-1711

by Swiss scholar Johann Jakob Scheuchzer, 1723 (public domain)

Encountering a traditional two-limbed lindorm in Switzerland, from

Itinera per Helvetiae Alpinas Regiones Facta Annis 1702-1711

by Swiss scholar Johann Jakob Scheuchzer, 1723 (public domain)Years passed by, and the boy became a youthful prince in search of a bride - but what he found was his brother, the lindorm. The prince had been riding around the perimeter of the vast forest encompassing the palace when, without warning, a huge ophidian head had emerged from a thorny bush directly ahead. Rearing up until its green-scaled body resembled a towering tree, the lindorm gazed down at the youth with unblinking eyes of amber that effortlessly penetrated his innermost thoughts. And as the prince stared back, mesmerised and motionless before this monstrous entity, he heard its voice, intoning deep within his mind - a voice that assured him with cold, reptilian detachment and certainty that he would never find a wife until he, his elder brother, had obtained the true love of a willing bride.

Accordingly, over the next few months a succession of village maidens were given to the lindorm, in the hope of overcoming this barrier to the young prince's quest for a bride. Needless to say, however, none of the maidens were thrilled at the prospect of marriage to a lindorm, so none came willingly - and, inevitably therefore, none was accepted by the monster. The situation seemed irreconcilable - until one day, that is, when the next maiden selected to be the lindorm's bride had the good fortune to encounter beforehand the soothsayer whom the queen had consulted all those years ago. After listening sympathetically as the maiden spoke of her impending plight, the soothsayer whispered into her ear some words of advice that swiftly replaced her sadness with a smile of joy.

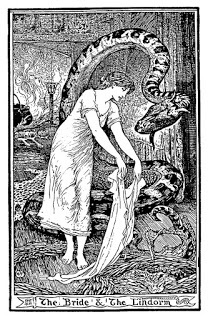

The maiden instructing the lindorm to shed its first skin, as portrayed by Arthur Rackham (public domain)

The maiden instructing the lindorm to shed its first skin, as portrayed by Arthur Rackham (public domain)That night, the maiden was presented to the lindorm, who gruffly told her to take off her dresses - of which she seemed to be wearing a surprising number. She agreed to do this - but only after extracting from the lindorm the promise that for every dress she took off, it would shed a layer of skin. This it did, until only a single layer remained - and until the maiden was clothed in just a single robe.

The maiden removing her first dress, watched closely by the lindorm after shedding its first skin as demanded by her - illustrated by Henry Justice Ford (public domain)

The maiden removing her first dress, watched closely by the lindorm after shedding its first skin as demanded by her - illustrated by Henry Justice Ford (public domain)Despite remembering the soothsayer's words, it was not without a degree of nervousness that she then removed this final gown and stood still, and naked, before the great dragon.

The lindorm moved towards her, and the maiden tensed - fearing yet desiring what was to come, for if the soothsayer had spoken truthfully to her there would be great happiness, and great love, ahead. And so she stood erect, motionless, as the serpentine monster leisurely, almost tenderly, enveloped her body in its scaly coils. She had expected them to feel cold and slimy, and was therefore pleasantly surprised by their warmth and softness - embracing and caressing her in their muscular folds.

Even so, she felt a flicker of terror rising within her - a desire to close her eyes, to scream, to flee, to do anything rather than remain here. Then the words of the wise old soothsayer came back to her, calming her mind, and she relaxed again.

Gazing about her, she noticed that the lindorm's last layer of skin was so thin as to be almost translucent, and was beginning to peel away, folding back upon itself like a cluster of withered leaves. At the same time, a strange green mist manifested all around, bathing the lindorm in a viridescent haze until she was aware of the creature's continuing presence only from the embrace of its sinuous body.

Gradually, however, the mist dispersed - and revealed that she was no longer wrapped within the serpentine coils of a lindorm after all, but within the firm arms of the most handsome man she had ever seen!

A somewhat Oriental-looking lindorm (public domain)

A somewhat Oriental-looking lindorm (public domain)The soothsayer had indeed spoken truthfully - by following her instructions, the enchantment that had incarcerated him within the guise of a lindorm had been dispelled, and here was the elder prince, heir to the country's throne, and for whom the maiden would indeed be a very willing bride. The joyful marriage took place without delay, and after the old queen had given her blessing to the newly-weds, who were now the new king and queen, she felt someone lightly tap her shoulder.

It was the soothsayer, who revealed to her the information that she had not stayed to hear all those years ago - namely, make sure that she peeled both onions before eating them!

This ShukerNature blog article is excerpted from my book Dragons: A Natural History (1995). See also my more recent book, Dragons in Zoology, Cryptozoology, and Culture (2013), for detailed coverage of lindorms in mythology, cryptozoology, and natural history.

Published on June 07, 2017 17:54

June 5, 2017

ENCOUNTERING THE CHING SHIH - A VAMPIRE FROM CHINA

The ching shih (© Andy Paciorek)

The ching shih (© Andy Paciorek)In China, bloodsuckers are both plentiful and petrifying, but few are feared as greatly as the ching shih...

After another back-breaking day planting rice in the water-logged paddy fields near his village, the young peasant boy was looking forward to returning home, where he would stand before the fire until he felt warm and dry again. Cheered by these thoughts, he failed to notice at first that he was not alone as he walked away from the fields and on towards his village.

Just a little way behind him, a strange luminous orb, roughly the same size as his own head, was floating above the ground, but not in a passive, directionless manner. Had anyone been watching, they would have seen that this odd sphere was purposefully following the boy, drawing ever nearer, and glowing ever brighter, casting an eerie, unholy light upon his back.

Call it instinct, a sixth sense, or whatever you will, but suddenly the boy ‘felt’ that something evil was approaching. In panic he whirled around - and then he saw it!

Instinctively, he pulled back, gasping in terror as the mysterious sphere, now floating directly before him, rapidly expanded until it matched him in size. And as he gazed at it, almost mesmerised by its weird, uncanny light, the sphere took form and shape, metamorphosing into what the boy would have discounted as a horrific creature of nightmare – had he not been wide awake.

The sphere was now a grotesque humanoid figure, its tall thin body as shrivelled as an animate corpse, and covered in long green fur imbued with the lurid flickering pallor of decay and death. Thick strands of lifeless hair fell down upon its shoulders, and a wispy straggling beard hung from its chin. But all that the boy saw were its eyes – blazing like twin coals of hellfire.

He knew only too well the identity of this monstrous entity – like every child, he had been warned many times that such demons lay in wait beyond the safety of his village’s perimeter – but he had prayed that he would never encounter one. It was a ching shih – the deadliest form of Chinese vampire. And despite its emaciated appearance, it was also the strongest.

Sure of its power over the boy, the vile creature grinned malevolently, revealing an array of small but razor-sharp teeth that would soon pierce the boy’s body to drain it of blood, but first he needed to be killed. And so the ching shih opened its mouth wide, sucking in a deep intake of air. Moments later, it would blow it back out, directly into the boy’s face, to suffocate him with its toxic, foetid breath.

But in those few moments, a voice spoke to the boy deep inside his mind – the voice of his mother, urging him to flee back to the paddy fields, flee and never look behind him, not even for an instant, until he had reached them.

Immediately, the boy turned and raced away, so rapidly that the ching shih was startled, not expecting his sudden burst of activity. But then it began to chase after him, and as the boy ran on, he could hear the pounding of the ching shih’s feet close behind, and feel the heat of its foul breath upon the back of his neck.

The paddy fields lay just ahead, separated from him only by a stream, and as the boy’s pace slackened, exhausted from his headlong flight, he heard his mother’s voice again, telling him to leap over the stream into the fields. And then he remembered – like all Chinese vampires, the ching shih cannot cross running water. Summoning up his last atom of strength, the boy leapt, half-stumbling from weariness, but somehow he succeeded in clearing the stream, almost as if his mother had been there beside him, lifting him over its flowing water.

Standing partly submerged in the paddy fields, only then did the boy finally look back, and there stood the ching shih, on the stream’s far side, unable to cross, its eyes phosphorescent with malice. It opened its mouth, letting forth a deafening roar of impotent rage, then its form shivered and diminished, transforming once more into a glowing sphere that bobbed in the air before the stream but dared not float above it.

Suddenly, the sphere moved back, and sped swiftly away, soon vanishing into the distance. Only then, very cautiously, did the boy set off for home again, but keeping the stream beside him, not recrossing it until he saw his village’s friendly welcoming lights - very different indeed from the loathsome orb of evil that had so nearly claimed him as its latest victim.

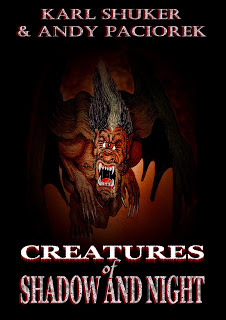

This ShukerNature blog article is excerpted from Creatures of Shadow and Night , a book-in-progress written by me and illustrated by fantasy artist Andy Paciorek.

Published on June 05, 2017 16:16

June 2, 2017

THE LIGHTBULB LIZARD OF BENJAMIN SHREVE - ILLUMINATING A HERPETOLOGICAL CONTROVERSY FROM TRINIDAD

Artistic representation of the Trinidadluminous lizard's possible appearance when glowing, as based upon Ivan T. Sanderson's claim (© Philippa Foster)

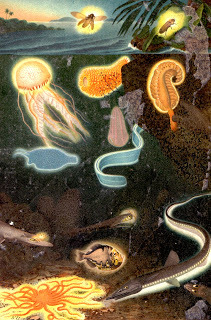

Artistic representation of the Trinidadluminous lizard's possible appearance when glowing, as based upon Ivan T. Sanderson's claim (© Philippa Foster)Among the fishes and several different taxonomic groups of invertebrate (including comb jellies, cnidarians, molluscs, insects, centipedes, millipedes, crustaceans, and annelid worms) are many bioluminescent species. That is, living creatures which actively carry out chemical processes to produce and emit light.

Officially, however, there are no bioluminescent species among the terrestrial vertebrates - but claims have been made that there may in fact be a notable exception of the reptilian kind.

I first learnt about, and then duly investigated, this fascinating yet surprisingly little-known case back in the mid-1990s, and here is what I uncovered at that time, followed by the extraordinary revelations that have occurred since then – yielding in this present ShukerNature blog article of mine the most comprehensive account ever published online.

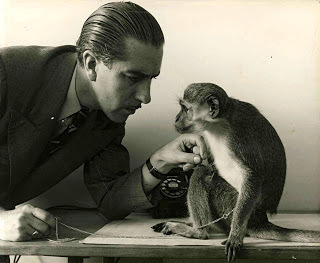

A selection of fully-confirmed bioluminescent creatures depicted in a vintage illustration from 1890 (public domain)

A selection of fully-confirmed bioluminescent creatures depicted in a vintage illustration from 1890 (public domain)In March 1937, during an animal collecting trip to the West Indies, American zoologist and cryptozoologist Ivan T. Sanderson visited Mount Aripo (aka El Cerro del Aripo), at 3,084 ft high the loftiest peak in Trinidad and part of this island's Northern Range. He had been capturing some freshwater crabs in a series of dark subterranean pools there when he suddenly spied a faint light in a crevice beneath a ledge. The light promptly went out, but Sanderson was curious to discover its source, so he flashed his torch into the crevice - and was most surprised to find a small lizard.

Attempting to coax it into his net, Sanderson gently tickled the lizard, but instead of running out it turned its head away - and as it did so, Sanderson was very startled to see both of its flanks momentarily lighting up "...like the portholes on a ship". When he finally succeeded in capturing it, this remarkable reptile lit up again, glowing brightly in his hand with a pale greenish hue that Sanderson subsequently likened to the glow produced by the hands and figures of a luminous watch.

As zoologists were previously unaware of any bioluminescent lizards, Sanderson was very thrilled by his discovery, which he documented in his book Caribbean Treasure (1939). Ironically, however, apart from its unique glowing ability the lizard, which was a male, seemed relatively nondescript in general appearance - with a long tail but short legs, a sharply-pointed muzzle, dark brown upperparts, and rosy salmon-pink underparts (turning yellow under its head) surfaced with large rectangular scales of plate-like form.

Ivan T. Sanderson's book Caribbean Treasure (© Viking Press, reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis only)

Ivan T. Sanderson's book Caribbean Treasure (© Viking Press, reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis only)Its only distinctive features were its body's lateral eyespots or 'portholes', constituting a series of large circular black blots running from the neck to the groin on both flanks, because each of these blots contained a vivid white bead-like spot. And it was these spots that were the source of the lizard's apparent luminescence, as determined by Sanderson during some basic experiments:

We made it [the lizard] hot and cold, and moist and dry alternately; we blew a loud whistle in its ear, we tickled it, and we subjected it to flashes of bright light...This creature seemed to produce its light in response to sudden emotional disturbance, rather than through actual physical reactions...The loud whistle, sudden winds, and flashes of light greatly agitated our lizard, causing it to switch on its 'portholes'. We noticed that this light was much brighter the first time it was switched on after the animal had been quiescent for a period, and more especially after it had previously been subjected to intense illumination.

Eventually, Sanderson shipped off his amazing little lizard to the British Museum (Natural History) in London, where it was studied in detail by fellow zoologist H.W. Parker. It was found to belong to a species already known to science (indeed, Parker himself had formally named and described it in 1935), but only just. An exceedingly rare member of the tejid (aka tegu) family Teiidae, and normally measuring 11-15 cm long, it was called Proctoporus (=Oreosaurus) shrevei (in honour of the very gifted American amateur herpetologist Benjamin Shreve), and had hitherto been represented in scientific collections only by a single preserved juvenile and one preserved adult female. Sanderson's specimen was therefore the first male of this species to have been brought to scientific attention, and until now no-one had suspected that it may be bioluminescent when alive.

Proctoporus shrevei

(copyright holder presently unknown to me despite my having made considerable efforts to discover this; reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis only)

Proctoporus shrevei

(copyright holder presently unknown to me despite my having made considerable efforts to discover this; reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis only)During his visit to Trinidad, Sanderson collected seven more individuals of this species, and as preserved specimens these too were examined by Parker. In a paper published by the zoological journal of London's Linnaean Society in 1939, Parker revealed that it was sexually dimorphic, with only the males sporting the distinctive 'porthole' markings (a further reason why no bioluminescence had been reported from the specimens procured prior to Sanderson's), and that in every porthole the epidermis of the white bead at the centre was less than half the thickness of the epidermis of the black ring surrounding it. In addition, the white bead's epidermis was transparent, lacking any form of pigment. In other words, each porthole literally constituted a black-edged circular window.

How the portholes functioned, however, remained a mystery, because Parker found no associated nerve endings or an increased blood supply, thereby eliminating any likelihood that they were directly connected with the sensory or circulatory systems. Nor did he find any ducts connecting them with the exterior, or any complex lenses or reflecting structures.

Whatever they were, therefore, these portholes were clearly very simple in structure, and Parker offered three possible explanations for their luminosity. In life, the portholes may contain some substance that either glows when it breaks down (the principle of bioluminescence in various fishes), or glows when exposed to light (as with the paint used in luminous watches). The third option is that the transparent central beads of the portholes are underlain with reflective tissue. (A fourth possibility, that the portholes contain glowing bacteria which create their luminosity, can be rejected, because Parker did not report the presence of any bacteria within them.)

Ivan T. Sanderson as a young man (copyright owner presently unknown to me despite considerable searches made; reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis only)

Ivan T. Sanderson as a young man (copyright owner presently unknown to me despite considerable searches made; reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis only)Inevitably, the prospect of a luminous lizard duly attracted attention from several other zoologists, who studied specimens of P. shrevei and various related tejids to find out whether any of them really did glow - but none of them did! And so in 1960, reporting at some length in the journal Breviora their own negative findings with P. achlyens from Venezuela and Neusticurus [now Potamites] ecpleopus ocellatus from Peru (both of which possess porthole markings resembling those of P. shrevei), American biologists Drs Willard Roth and Carl Gans rejected Sanderson's claims regarding P. shrevei's bioluminescence.

Yet Sanderson was an extremely experienced field zoologist, and Parker's histological studies convinced him that the portholes were genuine luminous organs. So who was correct? If P. shrevei were the only bioluminescent species, this would of course render worthless any comparative studies with related species. Moreover, at the time of my own initial examination of this case, only one zoologist other than Sanderson had actually investigated luminosity with living P. shrevei specimens, and he may simply not have stimulated them sufficiently for them to light up. (I subsequently found out that this latter zoologist was Prof. Julian S. Kelly – see later.)

My above account presents the situation concerning Trinidad's intriguing 'glowing lizard' that I had uncovered during my mid-1990s investigations. Since then, however, much additional information has come to light (pun intended!), and, as I discovered after unearthing it, this extra data includes some very significant new insights into P. shrevei and its alleged bioluminescent capabilities.

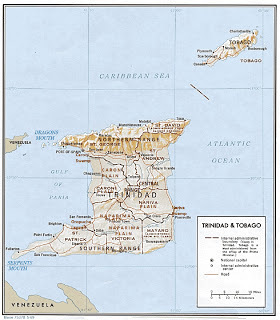

Map of Trinidad, highlighting its Northern Range, where Mt Aripo is (public domain)

Map of Trinidad, highlighting its Northern Range, where Mt Aripo is (public domain)First of all, it is nowadays deemed not to be a true tejid, so it is housed within a separate taxonomic family, Gymnophthalmidae, which contains many species. These are sometimes referred to as microtejids, because they are smaller than true tejids. Also, they tend to be quite skink-like in appearance, with certain species possessing reduced limbs.

I was pleased to learn that following further field studies, P. shrevei is no longer considered to be as rare as previously claimed. Indeed, the IUCN officially categorises it as being of Least Concern, and the IUCN Red List website states: "...although the distribution [of this species] is limited (with an extent of occurrence of 210 km2), the population trend appears to be stable, there are no current threats, and it occurs in at least two protected areas".

In addition, the IUCN assigns this species to the genus Riama, although quite a few other authoritative sources checked by me retain it within Proctoporus (so I shall do the same here for text consistency purposes), and refers to it via a very memorable common name that ties in with its supposed abilities – Shreve's lightbulb lizard. But is this name warranted?

Mark O'Shea lecturing at West Midlands Safari Park (© Ghaly-Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 3.0 licence

)

Mark O'Shea lecturing at West Midlands Safari Park (© Ghaly-Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 3.0 licence

)During my original investigations of Shreve's lightbulb lizard in the mid-1990s, I communicated with the West Midlands Safari Park's internationally-renowned herpetological expert Mark O'Shea, famed not only for his numerous scholarly publications but also for his fascinating TV show O'Shea's Big Adventurein which he travelled the world seeking rare or unusual reptiles and amphibians. Mark was very interested in this mystifying lizard species, and I was delighted when he subsequently visited Trinidad to look for it. His search featured in 'Exotic Island', the tenth episode of his show's first series, screened in 1999.

After arriving in Trinidad, Mark and his camera crew teamed up with Caesar, a local guide, and with Dr Victor Quesnel (named as Quinnel in some reports), a retired Trinidad-based economic botanist who was also a very knowledgeable all-round naturalist (he died in 2014). But before they set off on their arduous trek in the hope of emulating Sanderson's original success in encountering this island's luminous enigma in 1937, they were able to chat with Javrien Capriata (aka Capriata Dickson), who had been Sanderson's guide back then, and was now over 80 years old (Sanderson himself had died in 1973). Happily, Mark's search proved successful too, as the team found two specimens, a male and a female. (Moreover, during a much later expedition in 2008, Dr Quesnel actually rediscovered the specific cave where Sanderson had captured his lizard in 1937 but which had not been found since then; it is now known as Sanderson's Cave.)

These two lizards were duly videoed in a dark room by Mark's cameraman while they were being illuminated artificially and for a time after the artificial illumination had been turned off. The video was then viewed closely to see whether there were any signs of luminescence from them. Not surprisingly, the female lizard did not glow, as it lacked the all-important porthole markings. Conversely, the male did indeed appear to glow for a short time after the illumination had been turned off. Unfortunately, however, it was not possible to determine whether this constituted bona fide glowing from the lizard, or whether it was merely a trick of the light caused by filming and the camera adjusting to the darkness after the illumination had been extinguished.

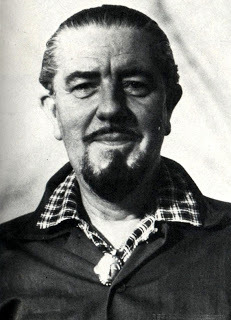

Ivan T. Sanderson in later years (© Dr Bernard Heuvelmans)

Ivan T. Sanderson in later years (© Dr Bernard Heuvelmans)During the first half of the year 2000, I exchanged a series of letters with herpetological specialist Hans E.A. Boos from Port of Spain, Trinidad's capital, who is extremely knowledgeable concerning the reptilian fauna of this island. Needless to say, therefore, one of the subjects that we discussed was P. shreveiand its alleged bioluminescence. Hans was very sceptical about this, and even more so concerning the reliability of Sanderson's eyewitness testimony (it has to be said here that Sanderson was well known for exaggerating claims at times, although this behaviour may have been caused by a brain tumour that developed over time and apparently contributed to his relatively early death, aged just 62).

In one of his letters to me, dated 22 January 200, Hans revealed that he had kept specimens of this lizard species in captivity for a considerable time but had never seen them light up. He also noted that both Dr Quesnel and Trinidad-based zoologist/newspaper columnist Prof. Julian S. Kenny had attempted to repeat the conditions reported by Sanderson but again had failed to achieve any success in stimulating the lizards to illuminate. In a subsequent letter, dated 14 April 2000, Hans mentioned to me that during the previous evening he'd had dinner with Dr Quesnel and had discussed fully with him the subject of P. shrevei. Quesnel had announced that he planned to try to collect a couple more specimens and this time arrange for high-quality histological sections to be prepared, with the tissues of the portholes properly fixed, in the hope of deducing something new regarding their supposed luminosity.

On 3 October 2004, the Trinidad Express newspaper published a short article written by Prof. Kenny that expanded upon Hans's comment concerning his investigations of Shreve's perplexing little lightbulb lizard. After referring to Sanderson's capture and claims regarding this species, Kenny revealed that American zoologist Prof. E. Newton Harvey (died 1959), a leading authority on bioluminescence, had once asked him to conduct an experiment to confirm his belief that Sanderson's claims were unfounded. The Harvey/Kelly experiment involved injecting some living specimens of P. shrevei with 1:10000, and 1:1000 doses of adrenalin. This treatment had already been shown to trigger light production in bioluminescent fishes, but it did not induce any reaction in the lizards.

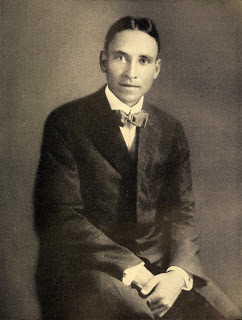

Prof. E. Newton Harvey (public domain)

Prof. E. Newton Harvey (public domain)Also in 2004, what is acknowledged to be the defining scientific paper dealing with this contentious species' reputed glowing behaviour was published in the Caribbean Journal of Science. One of its three authors was Dr Quesnel, who revealed that, in fulfilment of his hopes expressed to Hans Boos in 2000, he had indeed succeeded in conducting further field investigations of P. shrevei, in May 2001 and again in May 2002.

Two male specimens were captured in rock crevices near to a cave entrance at the summit of Mount Aripo – i.e. the same general locality as Sanderson's own discovery. After examining them in the field, Quesnel took them to a field station for further investigation, where they were studied under light and dark conditions at different times of the day. Yet no observations, either in the field or at the field station, revealed any light emission from the portholes. The same was true with a third specimen that had been captured and studied previously by Quesnel. Clearly, therefore, they did not appear capable of bona fide bioluminescence, i.e. the active generation of light by living organisms via chemical means.

But what about the prospect that the portholes were highly reflective, or perhaps even phosphorescent? (That is, reflecting incident invisible light as visible light but over a longer time period than in fluorescence and without heat.)

Vintage illustration from 1904 depicting a further selection of known bioluminescent creatures (public domain)

Vintage illustration from 1904 depicting a further selection of known bioluminescent creatures (public domain)To test this possibility, Quesnel directed high-intensity light from a xenon lamp at the lizards from varying angles. No light was emitted by the lizards, thereby demonstrating that they were not phosphorescent. However, light was readily reflectedby their porthole (ocellar) scales. As Quesnel et al. explained in their paper:

...if P. shrevei is observed along the same plane from which light is directed, the normally obvious white ocelli cannot be seen against the reflection from all other scales. But, when viewed from an angle oblique to the light source, the ocelli appear brighter, while surrounding scales show no reflection. By varying the angle of reflected light, an illusion is created that the ocellar scales are intermittently emitting light, thus providing an explanation of Sanderson's original account of the lizard "switch[ing] on its portholes." The illusion produced by the reflective scales also explains recent accounts, as well as Sanderson's description of the white ocelli "remain[ing] plainly discernable in a darkened box when the rest of the animal was invisible." The ocellar scales reflect and intensify ambient light while the darker ground coloration renders the rest of the lizard invisible in a dimly lit environment.

It was also noted that the illusory effect of the reflective porthole scales was enhanced by a varying in intensity of the black pigment surrounding these scales, and that this varying of the black pigment's intensity appeared in turn to be dependent upon the lizards' stress levels - because it became darker when the lizards were first handled, but faded somewhat after several minutes. The black pigment surrounding the porthole scales heightened their reflective effect, making them look a brighter white:

When viewed immediately after handling the lizards, the ocelli appear to pulse or fluctuate in brightness as the surrounding pigment changes intensity. After a quiescent period, the ocelli are still reflective but do not appear as bright as when the surrounding skin pigmentation is darker. Again, this could explain Sanderson's description that light from the lizard "was much brighter the first time it was switched on after the animal had been quiescent for a period of time," and "after one brilliant display... it refused to shine with full brightness." The darker dermal pigmentation, presumably associated with higher stress levels during handling, heightens the reflective appearance of the white ocellar scales. Decreased pigmentation during inactive periods gives the illusion that the lizard is not producing light at full intensity.

In short, these studies appear to have comprehensively refuted Sanderson's claims that Shreve's lightbulb lizard is bioluminescent. Instead:

...the lizard's unique scales act like small parabolic mirrors, reflecting light at oblique angles. The intensity of this reflectivity is, in turn, influenced by the intensity of surrounding dermal pigmentation and by the angle at which a lizard is oriented relative to a light source. Thus, ocellar reflection produces an illusion that light is emitted by P. shrevei at varying intensities, a phenomenon which obviously has confused a number of persons.

Partial view of the Northern Range, Trinidad, whose Mount Aripo is home to Shreve's still-mystifying microtejid (image cropped) (© Sanjiva Persad/Wikipedia –

CC BY 2.0 licence

)

Partial view of the Northern Range, Trinidad, whose Mount Aripo is home to Shreve's still-mystifying microtejid (image cropped) (© Sanjiva Persad/Wikipedia –

CC BY 2.0 licence

)Even so, one major light-related mystery concerning Shreve's very surprising microtejid still remains unsolved. Namely, why has so remarkable a morphological feature as this lizard's parabolic mirror scales evolved in the first place, and why only in male specimens?

These are questions that the study of Quesnel and his co-workers did not seek to answer, although, as they did point out, P. shrevei is a reclusive nocturnal species that inhabits dark localities and whose behaviour in the wild is unknown – all of which make any attempt at speculation fraught with difficulty. Nevertheless, it occurs to me that in view of their sex-specific and also age-specific occurrence, perhaps these scales' light-reflecting abilities function as a means of visual communication by which adult males attract adult females for mating purposes. An alternative option is that this light-reflection ability is used as a defence mechanism, to startle or ward off potential predators, but if this were true, why do only males possess the necessary scales?

Clearly it is high time that some comprehensive field studies were conducted in relation to this small yet very thought-provoking lizard, neglected by science for far too long, in the hope of finally shedding some much-needed light (in every sense!) upon the currently cryptic purpose(s) of its unique parabolic portholes.

The present ShukerNature blog article is a greatly expanded and fully-updated version of a short account that appears in my book Mysteries of Planet Earth (1999).

Published on June 02, 2017 20:58

May 15, 2017

HERMAN MELVILLE'S POLYNESIAN MYSTERY CAT - A WHALE OF A CRYPTO-TALE?

Did Herman Melville see a spectral black cat in Polynesia? (public domain)

Did Herman Melville see a spectral black cat in Polynesia? (public domain)For obvious reasons, it's always particularly interesting to learn of a possible cryptozoological encounter featuring a famous person. So I am greatly indebted to German mystery beast investigator Ulrich Magin for very kindly bringing to my attention recently the following example, hitherto-unpublicised online in a cryptozoological context.

The eyewitness in question is none other than Moby-Dickauthor Herman Melville, who documented his intriguing sighting – a veritable whale of a crypto-tale, no less! – in one of his non-fiction books, namely Typee: A Peep At Polynesian Life (1846). Describing time spent on the Polynesian island of Nukuheva in the Marquesas group, he included the following memorable lines:

As for the animal that made the fortune of my lord mayor Whittington, I shall never forget the day that I was lying in the house about noon, everybody else being fast asleep; and happening to raise my eyes, met those of a big black spectral cat, which sat erect in the doorway, looking at me with its frightful goggling green orbs, like one of those monstrous imps that tormented some of the olden saints! I am one of those unfortunate persons, to whom the sight of these animals is at any time an insufferable annoyance.

Thus constitutionally averse to cats in general, the unexpected apparition of this one in particular utterly confounded me. When I had a little recovered from the fascination of its glance, I started up; the cat fled, and emboldened by this, I rushed out of the house in pursuit; but it had disappeared. It was the only time I ever saw one in the valley, and how it got there I cannot imagine. It is just possible that it might have escaped from one of the ships at Nukuheva. It was in vain to seek information on the subject from the natives, since none of them had seen the animal, the appearance of which remains a mystery to me to this day.

What I find very intriguing about this report is how Melville ostensibly changed his opinion as to the nature of the cat during his description of it. For whereas in the first paragraph he referred to it as spectral and likened it to a saint-bothering imp, thereby implying that it appeared to be some form of paranormal, zooform entity, in the second paragraph he suggested that it may have escaped from a visiting ship, thus indicating that it was merely some absconded kitty of the corporeal kind.

True, his 'spectral' description may simply have been metaphorical rather than literal, but whatever the cat was, it was apparently not native to Nukuheva, and does indeed remain a mystery, not just in Melville's day either, but also right up to the present day, just over 170 years after his book was first published.

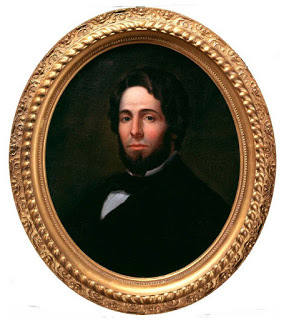

Herman Melville – oil painting by Asa Weston Twitchell (public domain)

Herman Melville – oil painting by Asa Weston Twitchell (public domain)

Published on May 15, 2017 06:11

May 12, 2017

SEEKING GLYCON - BLOND-HAIRED, HUMAN-HEADED, SERPENT-BODIED, AND VERY TALKATIVE!

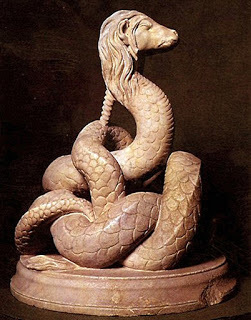

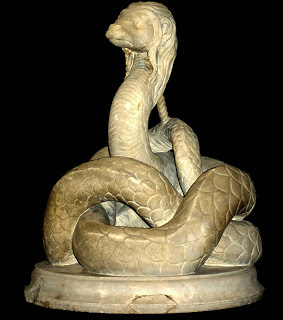

The statue of Glycon unearthed at Tomis, Romania, in 1962; right-hand view (public domain)

The statue of Glycon unearthed at Tomis, Romania, in 1962; right-hand view (public domain)A snake with a blond head of hair and the ears of a man would certainly be a marvel – but how much more so would one be that could also speak, and even foretell the futures of those who sought an audience with this wondrous ophidian oracle? All of this and much more – or, quite probably, a great deal less – was Glycon, the Roman Empire's incredible serpentine soothsayer.

In c.105 AD, a very controversial, enigmatic figure was born who would in time come to be known far and wide as Alexander of Abonoteichus, after the small fishing village on the Black Sea's southern coast that was his birthplace. Back in Alexander's time, Abonoteichus was located within the Roman province of Bithynia-Pontus (specifically within Paphlagonia, which was sandwiched between Bithynia and Pontus), but today it is contained within the Asian Turkish province of Kastamonu, and is now named Inebolu.

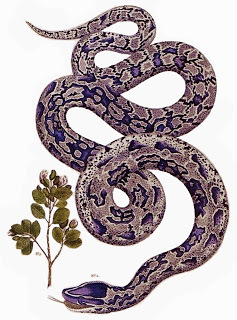

19th-Century illustration of an African rock python (public domain)

19th-Century illustration of an African rock python (public domain)Apparently very handsome and tall with an extremely charismatic personality, Alexander was originally apprenticed to a physician/magician, but after his mentor died Alexander met up with a Byzantine chorus-writer nicknamed Cocconas, and the two spent some time thereafter travelling around together, earning their living as fake magicians, quack doctors, and via other chicanery. Eventually, they reached Pella in Macedonia, and it was here that Glycon was born, so to speak, because this is where they purchased for just a paltry sum of money an extremely large and impressive-looking yet very tame snake (such serpents being commonly for sale in this locality at that time).

It was probably an African rock python Python sebae, as specimens of this very sizeable species (averaging 15.75 ft long but sometimes exceeding 20 ft) were apparently brought back to Rome, because it is depicted in Roman mosaics. Also, fertility-related snake cults had long existed in Macedonia, stretching back at least as far as the 4th Century BC.

Apollo after slaying the serpent dragon Python, engraving by W Wellcome, late 1700s (public domain)

Apollo after slaying the serpent dragon Python, engraving by W Wellcome, late 1700s (public domain)Alexander and Cocconas then journeyed to Chalcedon, a maritime town in Bithyna, where they lost no time in concealing inside its temple to the god Apollo a series of bronze tablets proclaiming that both Apollo and his serpent-associated son Asclepius, the Roman god of medicine and healing, would soon be appearing in Alexander's home village of Abonoteichus. They then contrived for these 'hidden' tablets to be found, and news of the tablets' sensational proclamations swiftly travelled widely, eventually reaching Abonoteichus itself, whose inhabitants promptly began building a temple dedicated to Apollo and Asclepius. It was then, in or around 150 AD, that the partnership of Alexander and Cocconas broke up, with Cocconas electing to stay in Chalcedon and continue producing phoney oracles, whereas Alexander was keen to put the next stage of their original plan into action, and so he duly set off back to Abonoteichus.

Using more fake oracles to proclaim himself as a prophet and healer, Alexander also claimed that his father was none other than Podaleirius, son of Asclepius himself and a legendary healer in his own right. Moreover, as signal proof of this, he arranged for a goose egg that he had 'discovered' inside Abonoteichus's newly-built temple to be publicly opened by him at noon on the following day in the village's marketplace before a crowd of curious but credulous onlookers, promising that a wonder would be revealed that would confirm all that he had alleged. And sure enough, when he opened the egg, a tiny snake emerged (one that supposedly he had subtly inserted inside before overtly 'discovering' the egg in the temple). As snakes were sacred to Asclepius (one common European species, the Aesculapian snake Zamenis longissimus, is actually named after Asclepius's Greek counterpart, Aesculapius), Alexander's grandiose claims were readily accepted by Abonoteichus's simple, unworldly villagers.

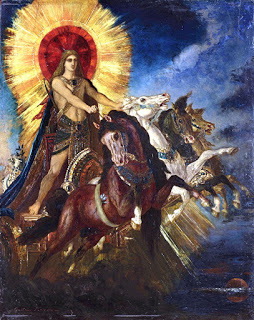

Statue of Asclepius and snake, 2nd century CE, found on the island of Rhodes, Greece (public domain)

Statue of Asclepius and snake, 2nd century CE, found on the island of Rhodes, Greece (public domain)As an interesting aside here: Chickens are often infected with parasitic gut-inhabiting worms, including the ascarid roundworm Ascaris lineata, a nematode species that can grow to a few inches in length (a related giant species in humans can grow to over 1 ft in length!). They are often passed out of the bird's gut when it defaecates. Unlike in mammals, however, the bird's gut and its reproductive system share a common external passageway and opening – the cloaca. Sometimes, therefore, an ascarid worm ejected from the gut finds its way into the bird's reproductive system rather than being excreted into the outside world, and moves into the oviduct. Once here, however, it becomes incorporated into the albumen of an egg, inside which it remains alive yet trapped when the egg is laid. But as soon as the egg is broken open to eat by some unsuspecting diner, the worm wriggles its way out of it and inevitably scares the diner, who frequently but mistakenly assumes that this unexpected creature is actually a tiny snake.

I wonder if such a scenario explained the above 'snake-inside-egg' incident involving Alexander? Or could the egg have actually been a genuine snake egg, but passed off to the ingenuous crowd by Alexander as an unshelled, undersized goose egg, perhaps?

Ascaris

, a large parasitic nematode (public domain)

Ascaris

, a large parasitic nematode (public domain)But that was not all. Alexander also stated that the baby snake was itself a deity, and that he would therefore be caring for it. After a few days had elapsed with the villagers not setting eyes upon this infant reptilian god, Alexander reappeared, once again thronged by awed spectators, but now only briefly and ensconced within a small dimly-lit shrine inside the temple where viewing conditions were far from ideal. Moreover, this time his huge, fully-grown pet snake from Pella was wrapped around his body, and he glibly announced that the baby serpent deity had miraculously matured directly into adulthood.

Yet even that incredible high-speed transformation was not the most surprising facet of Alexander's outrageous revelation. Instead of possessing a typical snake's head, the head of this remarkable creature apparently resembled that of a man, and sported an abundance of long blond hair sprouting liberally from it, as well as a pair of human ears! Moreover, it could even speak, and in the future would directly voice certain oracles or autophones to temples worshippers seeking guidance. Alexander announced that this astonishing entity was called Glycon, and constituted a new, living, physical manifestation or incarnation of Asclepius.

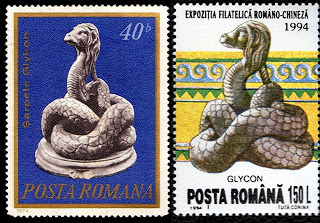

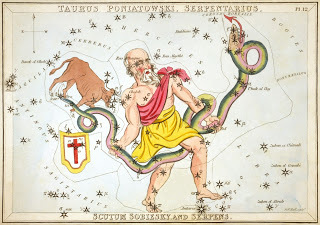

Two Romanian postage stamps, issued in 1974 and 1994 respectively, depicting the famous statue of Glycon unearthed in 1962 (public domain)

Two Romanian postage stamps, issued in 1974 and 1994 respectively, depicting the famous statue of Glycon unearthed in 1962 (public domain)Henceforth, Alexander's reputation, wealth, prestige, influence, and power, derived from his status as a celebrated prophecy-spouting soothsayer and in turn a highly-esteemed personage attracting acclaim and attention from all strata of Roman society, knew no bounds. In particular, the temple that he had established at Abonoteichus (by now a prosperous town) became a focus for fertility-themed worship and offerings by barren women wishing to become pregnant; and also for the very lucrative provision of oracles (always requiring prior receipt of payment). Moreover, Alexander was frequently consulted by public figures of high political standing anxious to solicit his ostensibly Heaven-sent advice regarding significant matters of state. The fact that sometimes his advice was by no means reliable seemed to be conveniently overlooked.