Karl Shuker's Blog, page 41

December 18, 2014

PERUSING THE PACARANA - A TERRIER-SIZED ‘TERRIBLE MOUSE’

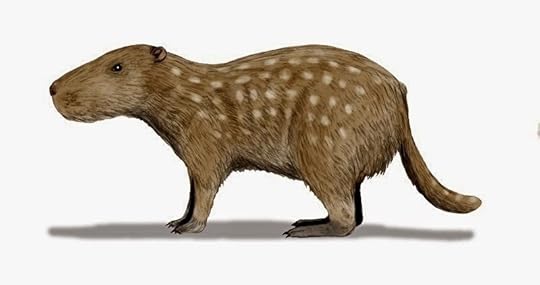

A captive pacarana (public domain)

A captive pacarana (public domain)There are over 2,200 species of modern-day rodent currently known to science, but only a handful are so radically different from all others that they have been assigned an entire taxonomic family all to themselves. However, the extraordinary – and exceptionally large - rodent documented here (and which also happens to be one of my favourite mammals) has indeed received that rare accolade. Moreover, as will now be revealed, the history of its scientific discovery - and rediscovery - is just as remarkable as it is.

The year 1904 was a momentous year for mice, for it marked the rediscovery of a truly astonishing and extremely mysterious, controversial rodent that science had dubbed 'the terrible mouse', due to the fact that it was as large as a fox terrier!

Needless to say, any mouse the size of a small dog is no ordinary mouse, and in truth this species is not a bona fide mouse at all. If anything, it more closely resembles a long-tailed, spineless porcupine in general shape, and sports a handsome grey-black pelage decorated with longitudinal rows of white spots, which compares well with that of the South American common paca or spotted cavy Cuniculus paca, which is a fairly large relative of the guinea pig (but not the world's third largest rodent, as certain websites erroneously claim).

Common pacas (© HumedoTepezc/Wikipedia)

Common pacas (© HumedoTepezc/Wikipedia)Indeed, in its native Andean homeland, the 'terrible mouse' is known locally as the pacarana ('false paca'). Yet it is neither paca nor porcupine either. Instead, as noted above, it is sufficiently removed from all living rodents to require its very own taxonomic family, Dinomyidae, thereby making it one of the most important mammalian discoveries of the past 150 years - not to mention one of the most elusive. Several prehistoric relatives of the pacarana have subsequently been described from fossil remains, and some of these were quite enormous in size (one, Josephoartigasia monesi, which lived 4-2 million years ago during the Pliocene and early Pleistocene epochs, was the size of a bison and is the largest rodent presently known to have existed). However, no other living dinomyids have been discovered, thus making the pacarana the very last representative of its entire lineage.

Josephoartigasia monesi

reconstruction inspired by the pacarana (© Nobu Tamura/Wikipedia)

Josephoartigasia monesi

reconstruction inspired by the pacarana (© Nobu Tamura/Wikipedia)Measuring up to 100 cm long and weighing as much as 15 kg, the pacarana is the world's third largest living rodent (exceeded only by the capybaras and beavers – but not by the paca, see above), and was discovered in 1873 by Prof. Constantin Jelski, curator of Poland's Cracow Museum. Financed by Polish nobleman Count Constantin Branicki, Jelski was engaged in zoological explorations in Peru when, one morning at daybreak, he observed an extremely large but wholly unfamiliar rodent. It had very long whiskers and a fairly lengthy tail, and was wandering through an orchard in the garden of Amablo Mari's hacienda near Vitoc, in the eastern Peruvian Andes. He swiftly dispatched the poor creature, and sent its skin and most of its skeleton back to Warsaw, where it gained the attention of Prof. Wilhelm Peters, Berlin Zoo's director, who meticulously studied its anatomy. Recognising that this huge rodent represented a dramatically new species, by the end of 1873 he had published a scientific description of it, in which he named it Dinomys branickii - 'Branicki's terrible mouse'. The pacarana had made its scientific debut.

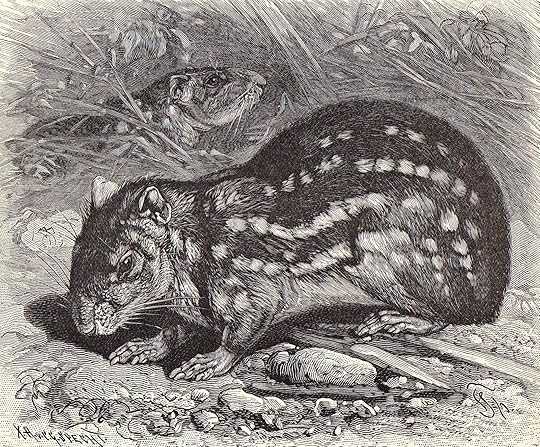

19th-Century engraving of the pacarana specimen encountered by Jelski

19th-Century engraving of the pacarana specimen encountered by JelskiPeters's studies disclosed that its anatomy was a bewildering amalgamation of features drawn from several quite different rodent families. In terms of its pelage and limb structure, it compared well with the paca, but unlike the five-toed (pentadactyl) configuration of the latter's paws the pacarana's each possessed just four toes. Many of its cranial and skeletal features (not to mention its long, hairy tail) also set it well apart from the paca, especially the flattened shape of the front section of its sternum (breast bone), and the development of its clavicles (collar bones).

19th-Century engraving of the common paca for comparison purposes with the previous engraving of a pacarana

19th-Century engraving of the common paca for comparison purposes with the previous engraving of a pacaranaCertain less conspicuous features of its anatomy were reminiscent of the capybara, but various others (including the shape of its molar teeth) corresponded most closely with those of the chinchillas. There were also some additional characteristics that seemed to ally it with the West Indies’ coypu-like hutias. Little wonder then that Peters elected to create a completely separate taxonomic family for it!

The pacarana was clearly a major find - yet no sooner had it been discovered than it vanished. For three decades nothing more was heard of this 'false paca', and zoologists worldwide feared that it was extinct.

Dr Emil Goeldi (public domain)

Dr Emil Goeldi (public domain)Then in May 1904, Dr Emilio Goeldi (1959-1917), director of Brazil's Para (now Belem) Museum, received a cage containing two living pacaranas (an adult female and a subadult male). These precious animals had been sent from the upper Rio Purus, Brazil, and proved to be extremely docile, inoffensive creatures, totally belying their 'terrible mouse' image. They were swiftly transferred to Brazil's Zoological Gardens, but tragically the adult female died shortly afterwards, following the birth of the first of two offspring that she was carrying.

Rare, early 20th Century photograph of a captive pacarana

Rare, early 20th Century photograph of a captive pacaranaIn 1919, a more unusual-than-normal pacarana was described by Alipio de Miranda Ribeiro. Instead of being greyish-black in colour, it was brown, so Ribeiro designated it as the type specimen of a new species, christened D. pacarana. Three years earlier, the first pacarana recorded from Colombia had been collected (near La Candela, Huila); in 1921, this became the type of a third species, D. gigas. During the early 1920s, a series of pacaranas was procured by Edmund Heller from localities in Peru and also Brazil, so that by the 1930s a number of museum specimens existed, which were then examined carefully by Dr Colin Sanborn in the most detailed pacarana study undertaken at that time. Publishing his findings in 1931, he revealed that D. pacarana and D. gigas were nothing more than varieties of D. branickii, which meant that only a single species existed after all.

Brown-furred (or faded black-furred?) taxiderm pacarana specimen at the Berlin Natural History Museum (© Markus Bühler)

Brown-furred (or faded black-furred?) taxiderm pacarana specimen at the Berlin Natural History Museum (© Markus Bühler)A rarely-glimpsed, nocturnal inhabitant of mountain forests, the pacarana feeds on leaves, fruit, and grass, usually associates in groups of four and five, and is hunted as a source of food by its Indian neighbours, but little else is known about its lifestyle in the wild state. It is currently classed as a vulnerable species by the IUCN, yet as a result of its secretive habits and relatively inconspicuous habitat it may be more abundant than hitherto suspected (nowadays it is known to be fairly common, for instance, in Bolivia’s Cotapata National Park).

Taxiderm pacarana at Tring Natural History Museum, Hertfordshire, England (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Taxiderm pacarana at Tring Natural History Museum, Hertfordshire, England (© Dr Karl Shuker)Due to this species’ notoriously elusive nature, however, down through the years zoos have prized pacaranas almost as much as giant pandas - which is why early 1947 was a singularly memorable time for Philadelphia Zoo. It was then that it received an innocuous-looking crate from legendary animal dealer Warren Buck of Camden, New Jersey, with the laconic remark: “Here’s a new one on me. Maybe you know what it is”. When the crate was opened, to everyone astonishment it contained a living pacarana! And just like Goeldi’s twosome, it proved to be delightfully tame and affectionate, showing no inclination to bite, and liking nothing better than to greet its visitors with a cheerful grunt and to sit upright on its hindlegs crunching a potato or carrot gripped firmly between its forepaws.

Of the handful of captive pacaranas obtained more recently and exhibited at such zoos as Zurich (the first to breed them), Basle, and San Diego (where I was fortunate enough to see my first live pacaranas in 2004), most have been of similarly pacific temperament. Indeed, they actively seek out their human visitors to nuzzle them and rub themselves against their legs almost like cats, or even to be picked up and carried just like playful puppies - truly a species with no desire whatsoever to live up to its formidable Dinomys designation!

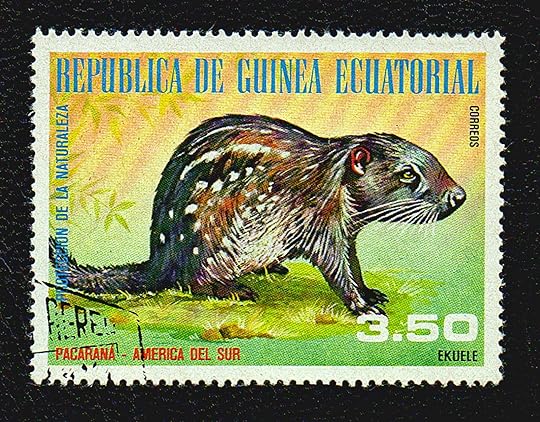

Pacarana depicted on a postage stamp issued by Equatorial Guinea

Pacarana depicted on a postage stamp issued by Equatorial GuineaFinally: Demonstrating that not only the pacarana but also the true pacas may well have some extra-large surprises in store for science is an exciting recent discovery made in Brazil by Dutch zoologist Dr Marc van Roosmalen. There are three currently-recognised species of true paca. Namely: the above-mentioned common paca C. paca; the smaller, longer-furred, and less-familiar mountain paca C. taczanowskii; and Hernandez's mountain paca C. hernandezi, described and named as recently as 2010 after mitochondrial DNA analyses confirmed its separate taxonomic status from the mountain paca. These are almost-tailless rodents normally no more than 60 cm long (often less), averaging 7 kg in weight, and adorned with usually four longitudinal rows of white spots on each side of their blackish-brown-furred body

Mountain paca (© WebmasterRioblanco/Wikipedia)

Mountain paca (© WebmasterRioblanco/Wikipedia)However, just a few years ago, Marc encountered – and collected – in Brazil a much larger form of true paca, known locally as the paca concha. It appears to have a very wide distribution range, and is distinguished from the two recognised species by its greater size (weighing up to 13 kg), its lighter fur colour, and the merging of most of its spots into longitudinal lines.

The holotype of the currently-undescribed giant paca (© Dr Marc van Roosmalen)

The holotype of the currently-undescribed giant paca (© Dr Marc van Roosmalen)In a scientific paper currently awaiting publication, Marc has named this extra-large form as a new species. Several suspected specimens of giant paca are held at Brazil’s Museu Paraense Emilio Goeldi, where Marc’s holotype of this potential new species, killed for food by a local hunter on 28 May 2006 near Tucunaré, has been deposited. So perhaps Count Branicki’s false paca now has a rival among the real pacas in terms both of physical stature and of complete surprise to the zoological community, thanks to its unexpected discovery.

This ShukerNature post is an expanded version of my pacarana account in my Encyclopaedia of New and Rediscovered Animals .

Published on December 18, 2014 20:08

December 5, 2014

HORNED RODENTS, DEVIL'S CORKSCREWS, AND TERRIBLE SNAILS - REAL-LIFE PALAEONTOLOGICAL DETECTIVE STORIES

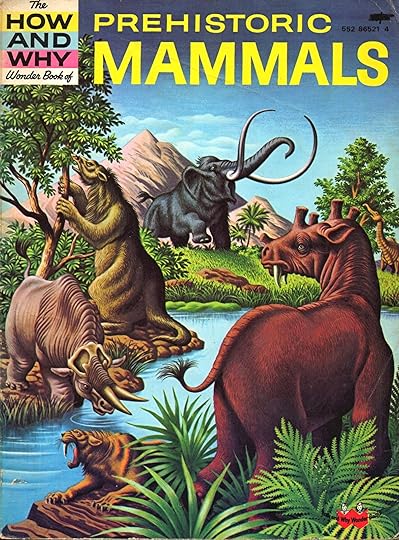

As a small child, this is the first picture that I ever saw of Ceratogaulus – in my trusty How and Why Wonder Book of Prehistoric Mammals, 1964 (© John Hull/Transworld)

As a small child, this is the first picture that I ever saw of Ceratogaulus – in my trusty How and Why Wonder Book of Prehistoric Mammals, 1964 (© John Hull/Transworld)Horned rodents, devil's corkscrews, and terrible snails may not seem to have a lot in common, but in reality these three ostensibly separate strands are intricately intertwined within a singularly unusual, interesting chapter in the history of zoological discovery, as now revealed.

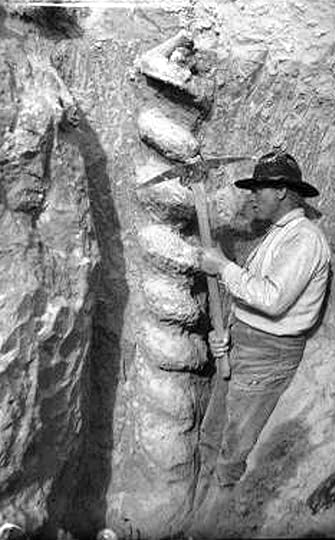

It all began in 1891, when geologist Dr Erwin H. Barbour from the University of Nebraska was shown some extraordinary formations by local rancher Charles E. Holmes in the Badlands of northwestern Nebraska, USA. Holmes and Dr Barbour colloquially dubbed them 'devil's corkscrews', as they did indeed resemble gigantic subterranean screws, each one penetrating several metres below the earth's surface, and constituting an elongated spiral of hardened earth.

Daimonelix

, illustration from 1892 (public domain)

Daimonelix

, illustration from 1892 (public domain)Dr Barbour proposed that these were the fossilised remains of giant freshwater sponges, his theory having been influenced by the belief current at that time that the deposits in which they occurred, and which dated to the Miocene epoch approximately 20 million years ago, were the remains of a huge freshwater lake,

Moreover, recalling the informal 'devil's corkscrew' nickname that he and Holmes had coined for them, in a short paper published by the journal Science in 1892 Barbour gave to these perplexing structures the formal scientific name Daimonelix ('devil's screw'), sometimes spelled Daimonhelix or Daemonelix in later works. Not everyone, however, was convinced by his theory that they were prehistoric sponges.

Daimonelix

diagram from Barbour's 1892 paper (public domain)

Daimonelix

diagram from Barbour's 1892 paper (public domain)A number of authorities favoured the possibility that they were artefacts, each one having been created by the intertwining of roots from some form of prehistoric plant that had subsequently rotted away (or even by pairs of prehistoric plants, one coiling tightly around the other), with the spiral-shaped space that they had left behind becoming filled with mud, ultimately yielding one of these remarkable giant underground 'screws'. And once subsequent research had shown that the deposits containing them were not the remains of a lake at all but were associated with semi-arid grassland instead, even Barbour quietly abandoned his freshwater sponge proposal in favour of the plant theory.

However, the name Daimonelix remained valid, because although scientific genera and species names are generally given only to organisms (modern-day or fossil), a notable exception to this nomenclatural rule concerns ichnofossils or trace fossils. These are fossils not of organisms themselves but of the traces left behind by them, such as footprints, burrows, coprolites, feeding marks, plant root cavities, etc, and they too receive scientific genera and (sometimes) species names.

Daimonelix

, fossil rodent burrow, Sioux County, Nebraska, Early Miocene, close-up (public domain)

Daimonelix

, fossil rodent burrow, Sioux County, Nebraska, Early Miocene, close-up (public domain)A third theory concerning the nature of the devil's corkscrews was put forward by Dr Theodor Fuchs and Edward Drinker Cope, who independently suggested in 1893 that they were the fossilised burrows of a Miocene rodent. This notion attracted appreciable interest – but if true, what kind of rodent could have been responsible? One candidate favoured in various popular-format publications for quite some time during the 20th Century was a creature no less extraordinary than the corkscrews themselves.

In 1902, Dr William D. Matthew published a paper in the Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History in which he formally described a new species of fossil rodent hailing from Colorado and dating back to the Miocene, but which was so different from all previously recorded species that it also required the creation of a new genus. Based upon a skull found in 1898, he named this novel creature Ceratogaulus rhinocerus – a very apt name, because, unique among all rodents at that time, it bore a pair of short but very distinctive vertically-oriented horns, sited laterally upon the dorsal surface of its nasal bones' posterior section.

Ceratogaulus

[aka Epigaulus] hatcheri, illustration from 1913 (public domain)

Ceratogaulus

[aka Epigaulus] hatcheri, illustration from 1913 (public domain)In later years, three additional horned species were discovered and named – Ceratogaulus anecdotus, C. hatcheri, and C. minor. Some of these were initially housed in a separate genus, Epigaulus(created in 1907), and C. minor has been reassigned by some workers to the related genus Mylagaulus, but the current consensus is that all four belong to Ceratogaulus. In addition, a fifth horned species, but which unequivocally belongs to the genus Mylagaulus rather than Ceratogaulus, was scientifically described as recently as 2012. Named Mylagaulus cornusaulax, it lived in western Oklahoma during the Miocene. Four other Mylagaulusspecies (not counting C. minor if classed as belonging to this genus) are also known, but none of these was horned.

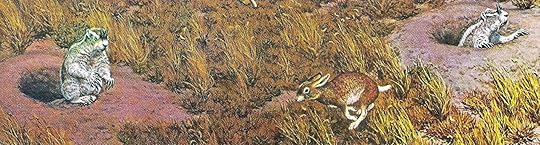

Known technically and collectively as mylagaulids, the horned rodents and several closely-related genera of non-horned species constitute an entirely extinct taxonomic family, existing from the Miocene to the Pliocene and (in the case of the horned species) unique to North America, but belonging to the squirrel lineage of rodents (Sciuromorpha). Moreover, examination of complete and near-complete skeletal remains has revealed that they superficially resembled marmots and other ground squirrels too, both in size (measuring roughly 60 cmlong) and in overall appearance – except of course for the five horned species' nasal horns, which make them the smallest horned mammals known to science. The horned species are sometimes colloquially referred to as horned gophers, but this is a misnomer, because gophers are only very distantly related to them. 'Horned marmot' would be a much more appropriate name.

Two Ceratogaulus specimens and a prehistoric hare (public domain)

Two Ceratogaulus specimens and a prehistoric hare (public domain)Suggestions that the devil's corkscrews could be the fossilised remains of burrows excavated by these rodents, utilising their horns, attracted interest, and remained in contention as the solution to this longstanding mystery until as recently as the 1970s (my little How and Why Wonder Book of Prehistoric Mammals was still supporting it back in 1964). However, studies focusing upon the precise conformation of their horns and speculating upon what this conformation indicated in relation to their possible functions revealed that such an idea was inherently and fatally flawed. Both the position and the shape of the horns are inconsistent with their being efficient digging tools.

By being located on the posterior rather than the anterior section of the nasal bones, the horns could not be used for digging through earth without the animal's muzzle constantly getting in the way, severely impeding the efficiency of this activity. Moreover, in later species the horns were positioned even further back than in the earlier ones, so it is evident that these rodents' evolutionary development became increasingly contrary to their horns being used as digging tools. The horns' very broad, thick shape also argued persuasively against their effectiveness as digging tools (it is nowadays believed that they served as defensive weapons instead). And so too did the telling fact that no remains of horned rodents discovered in direct association with devil's corkscrews had ever been documented.

Ceratogaulus hatcheri

skeleton (© Ryan Somma/Wikipedia)

Ceratogaulus hatcheri

skeleton (© Ryan Somma/Wikipedia)But if the horned rodents were not responsible for these structures, then what was? As far back as 1905, Dr Olaf A Peterson from the Carnegie Museum had revealed that some of them contained fossilised bones from Palaeocastor fossor and P. magnus - two prehistoric species of small terrestrial beaver. They had existed in Nebraska and elsewhere in North America's Great Plains region during the late Oligocene and Miocene epochs. However, it was not until 1977 that their responsibility for creating the devil's corkscrews was confirmed, via a scientific paper published in the journal Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, and authored by Drs Larry D. Martin and D.K. Bennett.

In it, the authors disclosed that these enigmatic underground spirals were in fact the helical shaft sections of Palaeocastorburrows, each complete burrow consisting of a single entrance mound, a long spiralled shaft, and a lower living chamber. These burrows also possessed interconnecting side-passages, and the authors' paper revealed that very extensive subterranean Palaeocastor colonies had existed (Dr Martin had discovered one that contained over 200 separate burrows), which were comparable in size and network complexity to the underground labyrinthine 'towns' or 'cities' produced by those modern-day North American ground squirrels known as prairie dogs.

Palaeocastor

reconstruction (© Nobu Tamura/Wikipedia)

Palaeocastor

reconstruction (© Nobu Tamura/Wikipedia)In addition, Martin's research at the University of Kansas had uncovered that the beavers excavated these screw-shaped burrow shafts with their incisor teeth, not with their claws (as various previous proponents of a rodent origin for such structures had wrongly assumed). For instead of finding narrow claw marks on the burrow walls, which is what he had expected, Martin instead discovered numerous broad grooves – which he was able to duplicate exactly by scraping the incisors of fossil Palaeocastorskulls into wet sand. The very regular spirals of their burrows' shafts (i.e. the devil's corkscrews) had been constructed by the beavers via a continuous series of either left-handed or right-handed incisor strokes.

And as final proof that Palaeocastor was indeed the engineer of the devil's corkscrews, the wider chambers immediately below these spiralled shafts were sometimes found to contain perfectly-preserved fossil skeletons of adult beavers and beaver cubs, thereby verifying that they were indeed the burrows' living quarters for these beavers.

Palaeocastor

fossil remains inside burrow's living chamber (public domain)

Palaeocastor

fossil remains inside burrow's living chamber (public domain)After almost a century, the mystery of North America's devil's corkscrews was a mystery no more; but across the Atlantic in England, an equally spectacular edifice of spiralled structure has continued to baffle the scientific world. Its name? Dinocochlea– 'the terrible snail'.

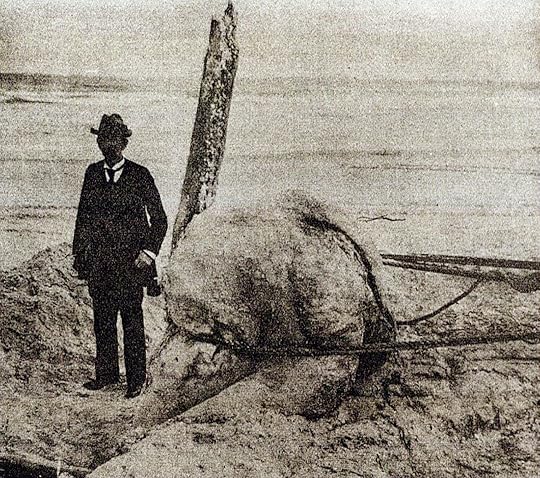

In 1921, during the construction of a new arterial road near Hastings in the Wealden area of Sussex, an enormous spiral-shaped object was uncovered and excavated from early Cretaceous clay after having been spotted by site engineer H.L. Tucker. Outwardly it resembled the spiralled shell of certain marine gastropod molluscs, in particular those of the genus Turritella, which is represented by numerous living and fossil species.

Fossil Turritella specimens (public domain)

Fossil Turritella specimens (public domain)Accordingly, when it was formally described in 1922 by London's Natural History Museum molluscan specialist Dr Bernard B. Woodward within the Geological Magazine, he named it Dinocochlea ingens, and did indeed categorise it as a fossil gastropod, albeit one of immense proportions.

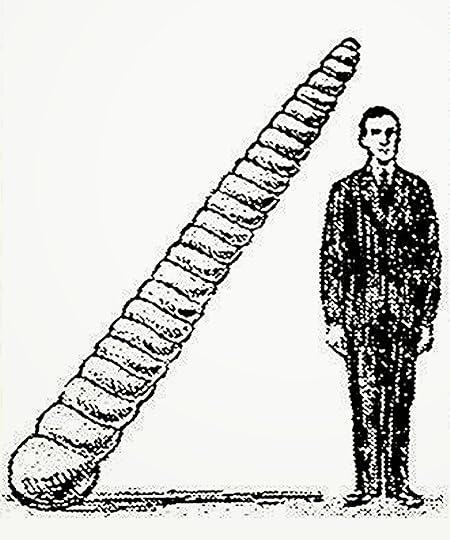

Measuring more than 2 m in length, it was far bigger than any other gastropod species known then, or now. However, this identification incited much controversy.

Dinocochlea

in situ (public domain)

Dinocochlea

in situ (public domain)For whereas spiralled gastropod shells normally bear ridges and possess coils that taper to a point, Dinocochlea did not, and there were no shell traces preserved with it either. Its freakishly large size was also difficult to reconcile with a gastropod identity.

Recalling the devil's corkscrews of North America, was it possible, therefore, that Dinocochlea was actually the fossilised burrow of some still-undiscovered species of prehistoric rodent? Alternatively, bearing in mind that it was uncovered near to a quarry famous for the quantity of Iguanodon and other giant reptilian fossils discovered there, could it be a dinosaur coprolite (fossilised faecal deposit)? Once again, however, its gargantuan size (even for a coprolite of dinosaur origin!) and also its spiralled shape's very precise, regular form argued against this, as did the fact that there was no partially-digested organic material associated with it, which is normally the case with preserved coprolites. So what could this very curious, anomalous object be?

Dinocochlea

, 1922 newspaper image (public domain)

Dinocochlea

, 1922 newspaper image (public domain)In June 2011, palaeontologist Dr Paul Taylor from London's Natural History Museum (where Dinocochleahad been deposited following its discovery) officially presented a new and very plausible explanation.

In a paper published by the Proceedings of the Geologists' Association, he proposed that it had indeed originated as a corkscrew-shaped burrow, but a horizontal one rather than the vertically-oriented devil's corkscrews, and had not been created by any rodent but instead by a fossil species of capitellid polychaete worm known as a threadworm. Yet as these were only a few millimetres in diameter, how could so tiny a creature have produced such a monstrously huge trace fossil as Dinocochlea?

Dinocochlea

life-sized model and Dr Paul Taylor of London's NHM (public domain)

Dinocochlea

life-sized model and Dr Paul Taylor of London's NHM (public domain)Having examined cross-section specimens of it, which revealed that they were filled with concentric bands of sediment resembling the growth rings of tree trunks, Dr Taylor suggested that although initially very small, this worm burrow had acted as a nucleus for concretion growth (which is characterised by the presence of such rings or bands internally).

That is, the space originally created by the burrow would induce the movement into it of surrounding mineral cements, which would themselves then leave behind a space that would in turn induce the movement into it of more surrounding cements, and so on, until eventually, if conditions for its preservation were just right, what began as a tiny thin worm burrow would ultimately become enormously enlarged, yielding the very dramatic pseudo-gastropod, mega-burrow trace fossil that we know today as Dinocochlea.

An absolutely delightful cartoon version of Ceratogaulus (© Ursulav/deviantart)

An absolutely delightful cartoon version of Ceratogaulus (© Ursulav/deviantart)From horned marmots and burrow-digging beavers to devil's corkscrews and terrible snails-that-weren't, it is evident that however distant our planet's past may be, it still possesses the power to perplex, surprise, inform, and fascinate us in a myriad of different ways.

The very attractive front cover of the How and Why Wonder Book of Prehistoric Mammals (© John Hull/Transworld)

The very attractive front cover of the How and Why Wonder Book of Prehistoric Mammals (© John Hull/Transworld)

Published on December 05, 2014 13:03

November 25, 2014

SEEKING THE MISSING THUNDERBIRD PHOTOGRAPH - ONE OF CRYPTOZOOLOGY'S MOST TANTALISING UNSOLVED CASES

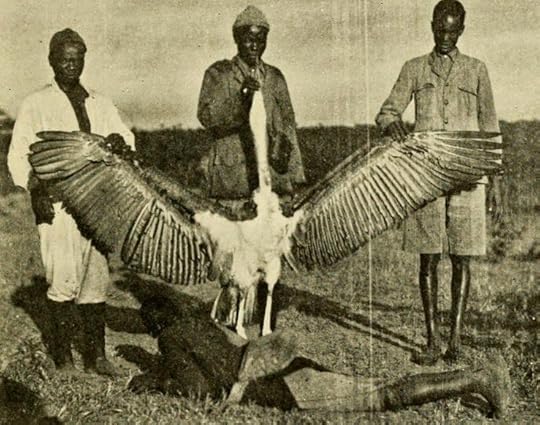

Could this very striking photograph of a large marabou stork standing upright with long beak open, huge wings held outstretched, and flanked by human figures have influenced some observers into later believing that they had seen the legendary thunderbird photograph? (public domain)

Could this very striking photograph of a large marabou stork standing upright with long beak open, huge wings held outstretched, and flanked by human figures have influenced some observers into later believing that they had seen the legendary thunderbird photograph? (public domain)One of the most perplexing sagas in the fascinating chronicles of cryptozoology is the long-running search for the thunderbird photograph, supposedly missing, presumed lost, for over a century. Here is an investigation that I conducted quite a while ago with regard to this mystifying picture, which has never previously been published in full, but is presented here now as another ShukerNature exclusive.

THE THUNDERBIRD OF TOMBSTONE

According to traditional Native American Indian lore, thunderbirds were enormous birds of prey that flew through the skies on immense wings, creating thunder when flapping them together, and sometimes even abducting unwary humans. Once dismissed as wholly mythical, many sightings have been made during modern times in the U.S.A., however, notably in the Pacific West and mid-West states, of unidentified yet seemingly gigantic condor-like or vulture-like birds soaring high through the skies and even occasionally encountered perched on the ground, which seem to be veritable 20th/21st-Century thunderbirds.

However, science needs something more tangible than eyewitness accounts to consider before accepting the existence of such astonishing creatures - which is why the thunderbird photograph's history has attracted such interest.

It all (allegedly) began back in 1886, when an Arizona newspaper called the Tombstone Epitaph supposedly published a very striking photograph, which depicted a huge dead pterodactyl-like bird with open beak and enormous outstretched wings, nailed to a barn and flanked by some men. This bird was reputed to be a thunderbird, and judging from the size scale provided by the height of the men standing alongside it, its wingspan appeared to be an awesome 36 ft! In other words, it was three times greater than that of the wandering albatross Diomedea exulans - the bird species currently holding the record for the world's biggest modern-day wingspan.

A wandering albatross in flight (© J.J. Harrison/Wikipedia; to see more great photos by J.J. Harrison, please subscribe to his Facebook profile

here

)

A wandering albatross in flight (© J.J. Harrison/Wikipedia; to see more great photos by J.J. Harrison, please subscribe to his Facebook profile

here

)Since then, countless people claim to have seen this same photo in various magazines published some time during the 1960s or early 1970s, but no-one can remember precisely where. Those publications thought to be likely sources of such a picture include Saga, True, Argosy, and various of the many Western-type magazines in existence during this period in America, but searches through runs of these publications have failed to uncover any evidence of it.

Nor has anyone come forward with a copy of this photo as published elsewhere, and the archives of the Tombstone Epitaph do not have any copy of it either.

A COUPLE OF HOAXED THUNDERBIRD PHOTOS

A number of photos claimed to be this evanescent, iconic image have been aired over the years, especially online, but these have all been exposed as hoaxes. To keep this section of the present article in proportion to the rest of it, I'll refrain from documenting every one of them here (the subject of a future ShukerNature article instead, perhaps?), and will just confine myself to two representative examples.

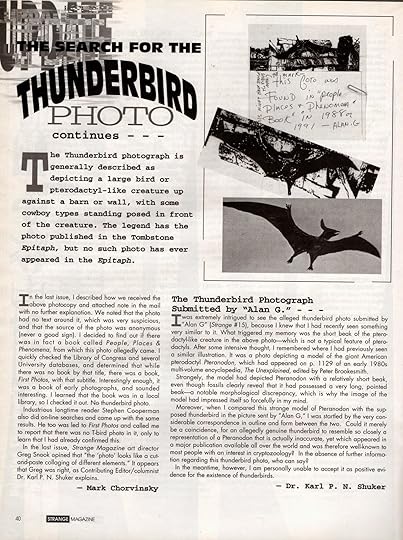

The first of these is one that I was personally able to expose, on behalf of Strange Magazine. Below is how it was written up and published in the Fall 1995 issue:

How I exposed a fake thunderbird photo in Strange Magazine (click image to enlarge it for reading purposes) (© Dr Karl Shuker/Strange Magazine)

How I exposed a fake thunderbird photo in Strange Magazine (click image to enlarge it for reading purposes) (© Dr Karl Shuker/Strange Magazine)The second hoax thunderbird photograph that I'm documenting here, and which is reproduced below, is of much more recent occurrence. Of unknown origin, it seemingly first appeared online in 2011, was rapidly included in numerous websites and blogs devoted to cryptozoology and to mysterious phenomena in general, and engendered much bemusement and controversy as to whether or not it was genuine, particularly as the thunderbird in it was a pterodactyl rather than a bird. Happily, however, when American student and ardent cryptozoological researcher Jay Cooney saw it, he realised that it looked familiar to him, so he conducted an internet image search of pterodactyl models. And sure enough, in one particular online stock-photo library he succeeded in finding a photograph of a model of the late Jurassic pterosaur Pterodactylus (click here to see it) that corresponded precisely with the pterodactyl in the supposed thunderbird photo. The latter's image had been lifted directly from the online stock photo of the Pterodactylus model. Another alleged thunderbird photograph duly discredited. Congratulations to Jay for his astute discovery – click here to access his own full coverage of it in his excellent Bizarre Zoology blog.

The hoaxed thunderbird photograph exposed by Jay Cooney (creator/s unknown)

The hoaxed thunderbird photograph exposed by Jay Cooney (creator/s unknown) LOOKING FOR THE LOST WITH A SEARCH THROUGH SAGA

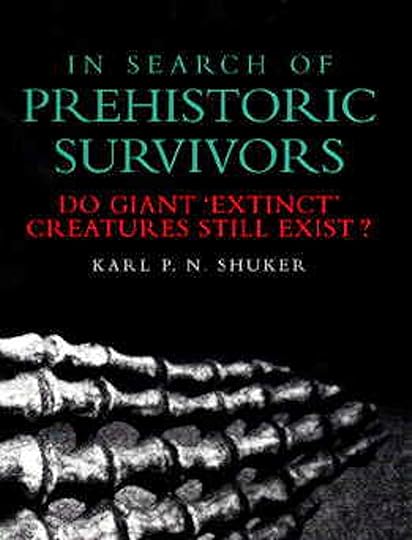

While researching for my book In Search of Prehistoric Survivors , published in 1995 and containing a large section dealing with thunderbirds, I decided to conduct some investigations of my own concerning this elusive picture.

I began them by focusing my attention upon Saga. This is an American magazine that has published many cryptozoological articles and illustrations over the years, and was deemed by longstanding thunderbird photo seekers such as the late W. Ritchie Benedict and the late Mark Chorvinsky to be a promising source of such a picture.

As there does not appear to be a complete or even near-complete run of this magazine on file in any British library, I contacted the Library of Congress in Washington DC, whose research specialist, Travis Westly, very kindly agreed to search through every Sagaissue published between January 1966 and March 1969 - a likely period during which this type of photo would have been published in Saga. Alas, no such picture was present, nor even a mention of any type of gigantic mystery bird.

THE THUNDERBIRD PHOTO ON TELEVISION?

Another widely-popularised claim that I decided to pursue is that a copy of the thunderbird photo was displayed on television by American cryptozoologist Ivan T. Sanderson during the early 1970s, when appearing as a guest in an episode of the long-running Canadian series 'The Pierre Berton Show'.

Consequently, I contacted the Audio-Visual Public Service division within the National Archives of Canada, to enquire whether a copy of the Sanderson episode in this series had been preserved. Unfortunately, however, I learnt from research assistant Caroline Forcier Holloway that she had been unable to locate this particular episode, and needed a precise production or release date for it in order to continue looking, because there were 597 episodes in this series still in existence, each of which contained more than one guest. Moreover, there were others that seemed to have been lost, so there was no guarantee that the episode containing Sanderson was among the 597 preserved ones anyway.

Ivan T. Sanderson on the cover of his book Ivan Sanderson's Book of Great Jungles (© Julian Messner)

Ivan T. Sanderson on the cover of his book Ivan Sanderson's Book of Great Jungles (© Julian Messner)However, one of my correspondents, Prof. Terry Matheson, an English professor at Saskatchewan University with a longstanding interest in the thunderbird photo, claimed in a letter to me of 22 September 1998 that Sanderson appeared on 'The Pierre Berton Show' not in the early 1970s, but actually no later than the mid-1960s. This is because Prof. Matheson vividly remembered seeing this episode and talking about it afterwards with a friend with whom he was working on the Canadian Pacific Railway as a summer job, and he only worked there from 1965 to 1967. Here is what he wrote:

"The particular episode of the programme...did not take place in the early 1970s. I remember watching the segment dealing with the thunderbird - part of an extended interview Pierre Berton had with Ivan Sanderson - from my home, when I was an undergraduate student at the University of Winnipeg in the mid-1960s. By the 1970s I was in graduate school in Edmonton. I know the programme could not have aired much later than 1965, because I recall discussing it initially with my mother and grandmother, who had also watched the show; with college friends, who made me the subject of much good-natured ridicule; and sometime later with a friend from Calgary whom I had met while employed on the Canadian Pacific Railway, as I was (over the summer months) from 1965 to 1967. I cannot recall the precise date of this conversation with my railroad friend, nor can I recollect the date I watched the programme with pinpoint accuracy, but would guess that it aired the winter before my first summer on the railroad, that is, 1964-65; at the very latest, the following year (1965-66). That might be a good place to start."

Prof. Matheson's confident placing of his well-remembered conversations concerning the above TV show within the mid-1960s, coupled with his precisely-dated period of employment on the railway in the 1960s, as well as his undergraduate studies also occurring exclusively in the 1960s, would certainly seem to disprove previous assumptions that this particular show was not screened until the early 1970s - unless, perhaps, it was re-screened at that time, following its original screening in the mid-1960s? However, his letter also contained another notable challenge to traditional assumptions regarding this show:

"To the best of my recollection, the photograph was not shown, at least not on this particular programme. I definitely recall Sanderson's allusions to the photograph, which he described vividly and with great precision. Although I can envision Sanderson's description as if it were yesterday - the bird nailed to the wall of the barn, the men standing in a line spanning the wingspan, etc - he did not, however, have the photograph in his possession when the interview took place, although he certainly claimed to have seen it. Incidentally, some time after this, Sanderson set up a society for the investigation of paranormal phenomena [SITU - the Society for the Investigation of The Unexplained]. I joined, and in response to my inquiry about the photograph, was told that they did not have a copy. Receiving this news led me to wonder at the time if the photograph might be an example of an urban myth or legend."

If, as would now seem to be the case, the thunderbird photo was not shown by Sanderson on 'The Pierre Berton Show' after all, one of the most promising avenues for tracing it - by seeking an existing copy of this specific show - has gone.

URBAN FOLKLORE, OR FALSE MEMORY SYNDROME?

Perhaps, therefore, as sceptics have often suggested, the thunderbird photo has never existed at all, and should therefore be dismissed as nothing more than an example of urban folklore. Having said that, there are others, including myself, who wonder whether at least some of those people who claim to have seen it have actually seen a superficially similar picture, depicting some large but known species of bird with wings outstretched, and years later have mis-remembered what they saw, erroneously believing that they had actually seen the thunderbird photo. Such an event would be a classic case of false memory syndrome.

Interestingly, one photograph that could certainly have inspired people to believe that they had seen the genuine thunderbird photo is one of a large marabou stork held with its beak open and its massive wings outstretched by some native men, reproduced at the beginning of this present ShukerNature post and again below. Tellingly, it appeared in a number of popular books worldwide during the early 1970s, including none other than the Guinness Book of Records, which at that time was second only to the Bible as the world's bestselling book, so was certainly seen by a vast number of people around the globe.

The iconic – and highly influential? – marabou stork image (public domain)

The iconic – and highly influential? – marabou stork image (public domain)I first proposed the marabou stork picture as a possible false memory trigger in relation to the real thunderbird photo (always assuming, of course, that the latter image really does/did exist!) way back in 1993 - in a letter sent to Bob Rickard at Fortean Timeson 15 February 1993 and in one sent to Mark Chorvinsky at Strange Magazine on 2 July 1993. My letter to Mark was subsequently published by Strange Magazine in its Fall/Winter 1993 issue (for a comprehensive Strange Magazine article of mine on this same subject, check out its December 1998 issue) . Here is what I wrote in my letter:

"Numerous people around the world believe that at one time or another they have seen the notorious "missing thunderbird photograph," allegedly published within a Tombstone Epitaph newspaper report in 1886 (see Strange Magazines #5, 6, 7, 11). In view of its extraordinary elusiveness, however, in many cases it is much more likely that their assumption is founded upon a confused, hazily recalled memory of some other, superficially similar picture instead – i.e. a "lookalike" photograph. A particularly noteworthy "lookalike" for the missing thunderbird photograph appeared on p. 35 of the British version of the Guinness Book of Records (19thedition, published in 1972), and is reproduced alongside this letter of mine. It depicts a large African marabou stork Leptoptilus crumeniferusstanding upright with its extremely large wings (which can yield a wingspan in excess of 10 ft.) held outstretched by some native tribesmen flanking it, and with its startlingly pterodactyl-like beak open wide. This picture thus incorporates a number of features supposedly present in the thunderbird photograph – a very big bird with a pointed pterodactyl-like head, and an extremely large wingspan, whose wings are outstretched, and flanked by various men. Bearing in mind that the photo is a very old one (possibly dating back to the first half of this century [i.e. the 20th Century]), and also that the Guinness Book of Records is a worldwide bestseller, and that this photo might well have appeared not only in the English version but also in many (if not all) of this book's other versions around the world [as far as I am aware, the same picture layout does indeed appear in all versions worldwide within any given year], it is evident that countless people will have seen it over the years, of which some may well have been unconsciously influenced by its striking (indeed, archetypal) image when contemplating the issue of the missing thunderbird photograph."

It is not even the only such photo of a marabou stork in existence either. Below is a second, albeit slightly less evocative one, which appeared in a book by Richard Tjader entitled The Big Game of Africa, and published in 1910:

Another photo of a marabou stork held with wings outstretched, this time from Richard Tjader's book The Big Game of Africa (public domain)

Another photo of a marabou stork held with wings outstretched, this time from Richard Tjader's book The Big Game of Africa (public domain)Returning to Prof. Matheson's letter to me, he raised an equally thought-provoking but very different point concerning false memory syndrome and the thunder bird photo:

"Although your suggestion that people's memories of a similar photograph might have been confused with that of the thunderbird is entirely possible, as I'm sure you know, Sanderson was a great raconteur, a man whose verbal gifts could cause anyone to imagine that they had actually seen something he had only described in words. Indeed, many years after watching the programme, I met an individual who had also seen the Berton interview and was initially positive that the picture had been shown."

Yes indeed, the power of verbal suggestion. Wars have been instigated as a result of the mesmerising oratory skills of certain leaders, let alone belief that a picture had been shown on a television programme when in reality no such appearance had occurred.

Incidentally, the December 1997 issue of Fortean Times not only contained a detailed account of modern-day thunderbird reports by veteran American cryptozoologist Mark Hall but also included a succinct account of my suggestion that the marabou stork photo in the Guinness Book of Records 1972 edition may have influenced some people in their belief that they had seen the missing thunderbird photo. Deftly combining our separate contributions to the subject, this issue's front cover duly sported a breathtaking illustration by artist Steve Kirk of a marabou stork-inspired thunderbird!

The spectacular marabou stork-inspired thunderbird artwork gracing the cover of the December 1997 issue of Fortean Times (© Steve Kirk/Fortean Times)

The spectacular marabou stork-inspired thunderbird artwork gracing the cover of the December 1997 issue of Fortean Times (© Steve Kirk/Fortean Times)GOING BACK TO THE VERY BEGINNING OF THE MYSTERY

Elsewhere in his letter, Prof. Matheson mentioned a line of investigation of his own that he had conducted in relation to the thunderbird photograph, and highlighted a fascinating and extremely pertinent fact, but one that seems to have attracted little or no attention from other investigators. What he did was to go right back to the starting point of the entire mystery – by writing directly to the Tombstone Epitaph, and enquiring whether such a picture had indeed ever appeared in their newspaper:

"In an interesting reply, they both denied any knowledge of the picture and also pointed out that the reproduction of photographs in newspapers was at that time – the late nineteenth century – not common anywhere in North America. In checking our local newspaper – the Winnipeg Free Press – to see if this was the case, I found that photographs rarely if ever appeared before the early 1900s, at least in that newspaper."

So is the thunderbird photograph fictitious, illusive rather than elusive, nothing more than a fable of our times, perpetuated into the present day by false memory syndrome – inspired in turn by visual lookalikes and seductive verbal suggestion?

Or, against all the odds, might it truly be real? Could there actually be a missing thunderbird photo, concealed in some old, yellowing magazine somewhere?

Next time that you clean out your attic and find a pile of dusty mags there, have a look through them before you throw them out – just in case. You never know what you may discover inside! And needless to say, if you do find the thunderbird photograph, be sure to contact me and let me see it!

I wish to dedicate this ShukerNature blog post to the memory of the late Mark Chorvinsky, the founder and editor of Strange Magazine and a wonderful friend to me, whose encouragement, friendship, and support during my formative years as a cryptozoological researcher and writer boosted my confidence and credibility enormously. Thank you always, Mark.

For plenty of additional information concerning putative modern-day thunderbirds, be sure to check out my book In Search of Prehistoric Survivors .

Published on November 25, 2014 02:24

November 24, 2014

OGLING THE OGRIDGE, OUTDOORS AND ONLINE - IDENTIFYING A LONGSTANDING MYSTERY BIRD OF MINE

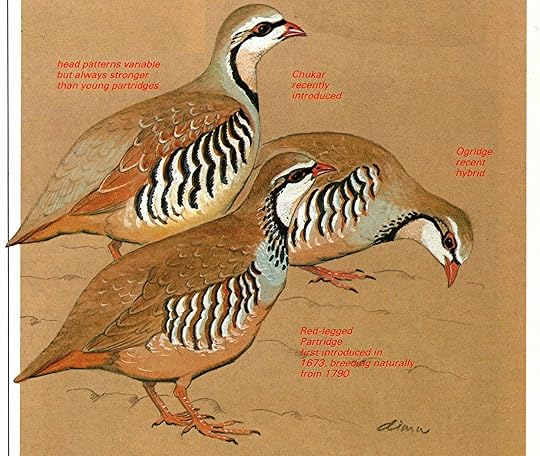

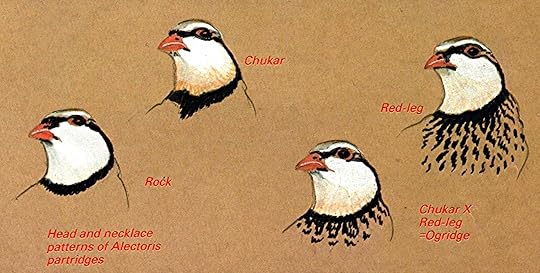

Chukar (top left), ogridge (middle right), and red-legged partridge (bottom left) - click to enlarge (original illustration source/copyright holder unknown to me, but illustration featured in Bird Watching, February 1988)

Chukar (top left), ogridge (middle right), and red-legged partridge (bottom left) - click to enlarge (original illustration source/copyright holder unknown to me, but illustration featured in Bird Watching, February 1988)As I've mentioned elsewhere on ShukerNature, even as a child I enjoyed cutting out and saving newspaper articles reporting unusual or controversial animals. Pasted in a series of scrapbooks, these humble offerings were the foundation of what gradually expanded during subsequent years into what is now my personal and still-expanding archive of material on cryptozoology and animal anomalies.

One of these early documents was a short newspaper report concerning a supposedly new type of bird dubbed the ogridge. Back in those very early, formative years as a budding cryptozoological archivist, however, my youthful zeal for saving such reports was not always matched by my remembering to note their complete bibliographical details. And so it was with this particular cutting: I'd noted down that it had appeared on 16 November 1972, but I'd neglected to record the name of the newspaper that had published it. However, I do recall that the newspaper in question was one of two London-based red-top tabloids – either the Sun or the Daily Mirror. So if I ever do need a full reference for it, this shouldn't be too difficult to track down.

Anyway, the report itself reads as follows:

THE OGRIDGE

New birds are rare these days but one new bird is the ogridge. The ogridge is bred from the partridge but its markings are a lot bigger and bolder. It is gentle, unlike a mere partridge which pecks other birds to death out of sheer boredom. And, to top it all, the ogridge is a much better sport. Partridges walk away from the gun. The ogridge knows better – it flies. The ogridge has been bred by Lincolnshire game breeders, Ormsby Games. They said yesterday that it is in great demand, with day-old chicks selling at 80p. After all, ogridges may be harder to shoot, but they're easier to live with.

Obviously, the notion of a new bird greatly intrigued me, and in the years that followed I sought to discover more about this avian novelty, seeking references to it in books, journals, library archives, etc, but all to no avail. Not a mention of the ogridge could be found by me anywhere (this was of course back in those grim, dark years before the instantly-available plethora of online information proffered by the internet existed!). So recalcitrantly elusive was the enigmatic ogridge, coupled by the somewhat whimsical, tongue-in-cheek write-up of the lone newspaper report on it that I had preserved back in 1972, that I eventually began to wonder if it was nothing more than a journalistic joke, created to amuse its readers but not to be taken seriously.

It was now the late 1980s, and one day I was browsing through some books in a local charity shop when I noticed a pile of magazines nearby. Idly flicking through them, I came upon a few issues of Bird Watching. Knowing that this magazine often carries reports and articles concerning rarities sighted in Britain or elsewhere, I started looking through them. One was the February 1988 issue, and as I thumbed through its pages I came upon an article by Ian Wallace entitled 'Whirring Wings and Cackles', whose subject was partridges in Britain. And there, in a full-colour plate depicting the various types of partridge on record from the U.K., was a portrait of…an ogridge!

Red-legged partridges (© Archibald Thorburn, 1915)

Red-legged partridges (© Archibald Thorburn, 1915)Needless to say, I lost no time in purchasing this precious publication that had verified the reality of the evanescent ogridge, and when I read the full article back home I discovered that it was a specially-bred hybrid of the red-legged partridge Alectoris rufa (a non-native species originally introduced into Great Britain from France in 1673 as an additional game bird to the native grey partridge Perdix perdix, and which has been successfully breeding here since 1790 in a fully-naturalised state) and the chukar A. chukar (another foreigner, native to Asia and southeastern Europe, and first introduced into Britain as yet another target for game bird shooters in 1972 – along with releases of its hybrid progeny, the ogridge).

Chukar (© Mdf/Wikipedia GNU FDL)

Chukar (© Mdf/Wikipedia GNU FDL)The mystery was finally solved. The ogridge did indeed exist, and was a red-leg x chukar crossbreed. However, as I learnt from Wallace's article, it was also something of an albatross – metaphorically speaking! – in that it had proved to be a rather undesirable addition to the British avifauna. This was because the red-legged partridge's gene pool here was becoming increasingly diluted by such hybridisation, the resulting interspecific gene flow potentially threatening the continuing existence of Britain's pure-bred red-leg stock, the latter now having to compete for survival with both the chukar and their crossbred creation the ogridge (which apparently was expected to be sterile but subsequently proved otherwise). Certainly in recent years red-leg numbers in Britain have declined.

As a result, the licence for permitting the introduction into the wild here of ogridges and pure-bred chukars was not renewed when it expired in October 1988, and all such introductions were officially banned in 1992. However, there are still plenty of both forms out there, especially in southern Britain, and escapes from captivity no doubt also occur from time to time.

Even for twitchers, their presence is problematic, due to their great outward similarities. Indeed, it took several years before any fairly constant plumage differences could be verified – prior to then, even certain birdwatching field-guides were depicting them incorrectly. Perhaps the most evident distinguishing characteristic between red-leg, ogridge, and chukar is their solid-black throat gorget and their throat colour immediately above it.

From left to right: close-up of the head and necklace patterns of the rock partridge Alectoris graeca (not occurring in the UK but native to southeastern Europe and closely related to the chukar and red-leg), chukar, ogridge, and red-leg – click to enlarge it (original illustration source/copyright holder unknown to me, but illustration featured in Bird Watching, February 1988)

In the red-leg, the gorget possesses a deep 'necklace' of speckles immediately below it and predominantly white plumage above it. In the ogridge, conversely, the depth of necklace present below the gorget is much-reduced, whereas immediately above the gorget is a rufous-buff crescent (though as with all hybrids, there is much variation upon this basic theme!). And in the chukar, there is normally no necklace at all below the gorget (though a few necklace-sporting specimens have been recorded), whereas immediately above it is a pronounced rufous-buff crescent.

In spite of its modern-day familiarity to ornithologists and game bird hunters alike, online coverage of the ogridge is surprisingly sparse. When preparing this present ShukerNature article, I could only find a handful of reports appertaining to it, and not a single ogridge illustration anywhere. Consequently, and presumably for the reasons outlined above, the ogridge failed to sustain, or possibly even stimulate, the degree of interest and enthusiasm predicted for it in my newspaper cutting from 1972 – the year in which the first specimens were released into the British countryside.

Not such an easy bird to live with, after all?

Complete colour plate featuring the chukar, ogridge, red-leg, and two other game birds (common quail and grey partridge) – click to enlarge it (original illustration source/copyright holder unknown to me, but plate featured in Bird Watching, February 1988)

Complete colour plate featuring the chukar, ogridge, red-leg, and two other game birds (common quail and grey partridge) – click to enlarge it (original illustration source/copyright holder unknown to me, but plate featured in Bird Watching, February 1988)

Published on November 24, 2014 02:17

November 23, 2014

GROUSING ABOUT THE RACKELHAHN – A SPECTACULARLY CROSS-TEMPERED CROSSBREED OF THE FEATHERED VARIETY!

19th-Century painting of a male rackelhahn

19th-Century painting of a male rackelhahnWhereas mammals on the whole are somewhat conservative as far as interspecific matings in the wild are concerned (all manner of exotic mammalian hybrids have of course been produced by deliberate captive breeding), birds show far less restraint in such matters, yielding all manner of spectacular crossbred creations. Some of these are famous, some are controversial, but all embody a fascinating montage of mixed morphology, yielding curious combinations of features drawn from both of their parental species so that they are at once similar to yet dissimilar from each of them.

One of my favourite examples of an interspecific avian hybrid (indeed, an intergeneric one if its two progenitor species are retained in the separate genera that they were long accorded before more recently being lumped back together within the same single genus) is not particularly well known outside gamebird hunting circles. Yet it is very distinctive in form as well as being quite large (and hence conspicuous) in size, and often uncompromisingly bellicose in behaviour too. Consequently, I felt that it was high time that this noteworthy bird receive some publicity here on ShukerNature. And so, without further ado, I give you…the rackelhahn.

Taxiderm specimen of a male rackelhahn (© Markus Bühler)

Taxiderm specimen of a male rackelhahn (© Markus Bühler)Also known as the rackelhane or rackelwild (all three names are apparently of Swedish origin, derived from the word 'rachla' - meaning 'snoring' or 'wheezing' - and refer to the curious pig-like grunting sounds that it is wont to give voice to in addition to combinations of the calls of both parental species), this interesting interspecific results from matings between two very readily-distinguishable species of grouse.

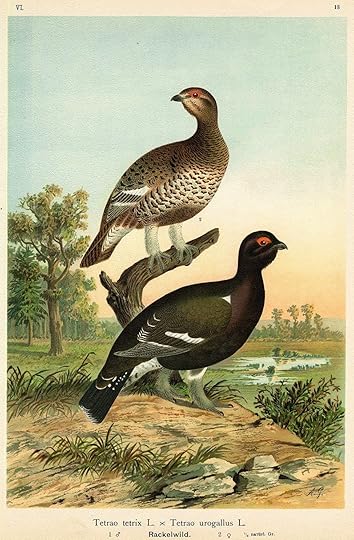

These are the Western capercaillie Tetrao urogallus and the Eurasian black grouse T. (=Lyrurus) tetrix, both of which occur across much of Europe and yield this hybrid throughout the zones of overlap within their respective distribution ranges, especially in Scandinavia. Having said that: because their ranges have become rather fragmented in modern times due to over-hunting, however, these overlap zones have diminished, and rackelhahn occurrence has decreased accordingly. Hence it is much rarer now than was once the case.

Male and female Eurasian black grouse (above) and male and female Western capercaillie (below)

Male and female Eurasian black grouse (above) and male and female Western capercaillie (below)Bearing in mind that the male capercaillie is considerably larger than the female black grouse, thereby making matings between them both difficult and unlikely, most rackelhahn specimens result from the reverse cross, i.e. between male black grouse and female capercaillies. Rackelhahn specimens also occur in regions where the distribution range of the Eurasian black grouse overlaps with that of the black-billed capercaillie T. urogalloides(native to eastern Russia as well as parts of northern Mongolia and China).

Another taxiderm specimen of a male rackelhahn (© Markus Bühler)

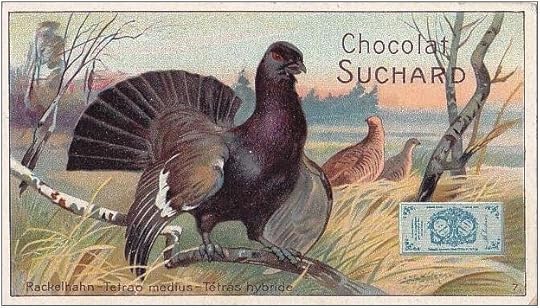

Another taxiderm specimen of a male rackelhahn (© Markus Bühler) Although long known to European naturalists (it was listed by Linnaeus back in 1758 when he was compiling his binomial system of nomenclature for plant and animal species), the rackelhahn was deemed by some to be a valid species rather than a hybrid, and thus received various binomial names, including Tetrao medius and T. hybridus (though as can be seen, such names clearly reflected the prevailing thought that it represented a form intermediate between the capercaillie and black grouse), but these were soon abandoned when its true, hybrid nature was confirmed by observations of successful matings in the wild between the two species.

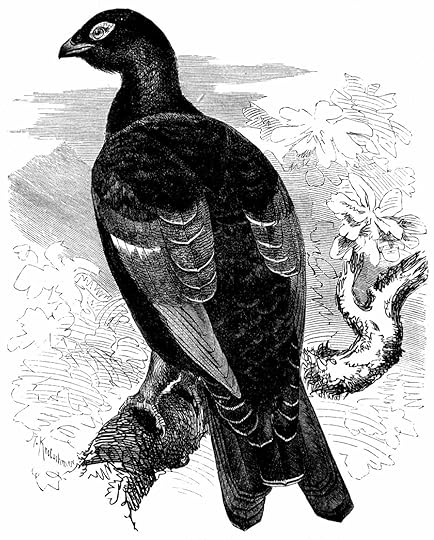

Male rackelhahn, engraving in Alfred Brehm's Animal Life, 1882

Male rackelhahn, engraving in Alfred Brehm's Animal Life, 1882Male rackelhahn specimens are much more common than females, but both sexes are apparently eager to mate. The first comprehensive description of the male rackelhahn's form was produced by Adolf Bernhard Meyer, who in 1824 also became the first person to describe the female rackelhahn's form – prior to then, there had only been unconfirmed speculations concerning the latter's appearance. Having said that, however, just like many other interspecific hybrids there is some degree of morphological variation between individual rackelhahn specimens, but in general terms they can be described as follows:

The male is intermediate in size between the larger male capercaillie and the smaller male black grouse, and is mostly dark in colour, with brownish-black shoulders and wings, plus deep metallic blue-purple to copper-red sheens upon its head, nape, chest, and sometimes the start of its back too. As in both parental species, it has a white spot upon each shoulder, and some specimens also have white spots upon the upper surface of their tail feathers and/or white tips to their tail feathers' underside. Its eyes' irises are brown, its eyebrow-wattles are bright red, and its beak is blackish-horn in colour. The terminal edge of its tail is semicircular, but sometimes has pronounced curving edges, reminiscent of the male black grouse's famously lyrate tail.

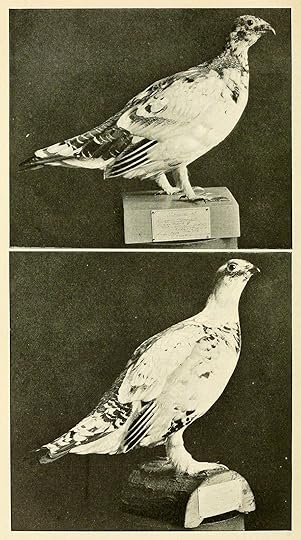

Female rackelhahn (above) and male rackelhahn (below), from Naturgeschichte der Vogel Mitteleuropas by Johann Friedrich Naumann, 1896

Female rackelhahn (above) and male rackelhahn (below), from Naturgeschichte der Vogel Mitteleuropas by Johann Friedrich Naumann, 1896Like the male, the female rackelhahn is intermediate in size between the larger female capercaillie and the smaller female black grouse, and can be readily distinguished from both via its blackish-brown plumage, sprinkled with brown, grey, and rust-red. The tail of some specimens has a relatively straight terminal edge like a female capercaillie's tail, whereas in others it is lyrate, like that of a female black grouse.

Male rackelhahn, engraving in Richard Lydekker's The Royal Natural History, 1895

Male rackelhahn, engraving in Richard Lydekker's The Royal Natural History, 1895Both the capercaillie and the black grouse exhibit what is known as lekking behaviour. In each species, males congregate together in an aggregation known as a lek, and engage in competitive displays in order to attract females for mating purposes. In areas where male capercaillies have been depleted due to over-hunting, female capercaillies will sometimes enter black grouse leks and mate with these male black grouse, yielding rackelhahn specimens. Sometimes, they will even mate with rackelhahn males, but offspring from these backcrossings have not been verified in the wild, though they have occurred in captivity. Due to the larger size of male capercaillies in relation to rackelhahn males, the latter do not enter capercaillie leks, but display only on the outskirts or margins of such leks.

Conversely, rackelhahn males do sometimes invade black grouse leks, and due to their much larger size and aggressive temperament they have been known to disperse these leks by intimidating and directly attacking, even occasionally killing, some of the male grouse there. They will also kill female black grouse, especially if the latter are indifferent to their advances, showing no inclination to mate with them. Having said that, there are also reports on file of rackelhahn males that have been frightened away by smaller but belligerent male black grouse, so the rackelhahn does not always triumph in such confrontations. Rackelhahn females that have mated with male black grouse have laid eggs, but the hatching of viable offspring from them does not seem to have been confirmed.

A male rackelhahn (© F.C. Robiller/Wikipedia)

A male rackelhahn (© F.C. Robiller/Wikipedia)A video of a male rackelhahn interloper displaying in a black grouse lek and attacking one of the male black grouse in the lek can be accessed here

An even more pugnacious male rackelhahn can be viewed here fearlessly attacking a hapless cameraman gamely attempting to photograph it!

And here three male rackelhahn specimens can be seen fighting each other in a black grouse lek at Landvik, Grimstad, Norway, on 1 May 1994; a week earlier, this lek had also been visited by a single female capercaillie

Male rackelhahn, taxiderm specimen at the Zoological Institute of the University of Tübingen, Germany (© Markus Bühler)

Male rackelhahn, taxiderm specimen at the Zoological Institute of the University of Tübingen, Germany (© Markus Bühler)It has sometimes been said that love is a battleground, and this is certainly true as far as warring, cross-tempered rackelhahn males are concerned!

Male rackelhahn portrayed on a card issued by Suchards Chocolate (© Suchards Chocolate)

Male rackelhahn portrayed on a card issued by Suchards Chocolate (© Suchards Chocolate)Incidentally, the rackelhahn should not be confused with another unusual grouse hybrid, the riporre - which is a hybrid of the Eurasian black grouse and the willow grouse Lagopus lagopus. Here are two riporre specimens from northern Sweden that were documented in 1904 by Dr Einar Lönnberg and had resulted from a successful mating between a male willow grouse and a female black grouse:

Published on November 23, 2014 12:30

November 22, 2014

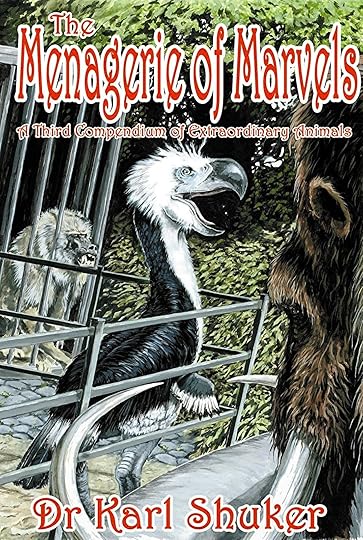

THE MENAGERIE OF MARVELS IS HERE!! – MY TRILOGY OF BOOKS ON EXTRAORDINARY ANIMALS IS NOW COMPLETE

My newly-published, 21st book –

The Menagerie of Marvels

(© Dr Karl Shuker/CFZ Press)

My newly-published, 21st book –

The Menagerie of Marvels

(© Dr Karl Shuker/CFZ Press)Until recently, I hadn't fully realised that the vast majority of my 21 published books consist of pairs or trilogies – in most cases, I hadn't planned this, it just seems to have happened.

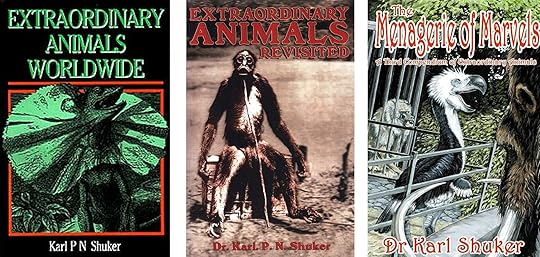

Thus I have written two books on controversial felids ( Mystery Cats of the World and Cats of Magic, Mythology, and Mystery ); two on dragons ( Dragons: A Natural History and Dragons in Zoology, Cryptozoology, and Culture ); two specific compilations of articles of mine that originally appeared in the magazines Fate and Fortean Timesrespectively ( From Flying Toads To Snakes With Wings and Karl Shuker's Alien Zoo ); two non-specific compilations of articles of mine, now updated and expanded but which originally appeared in a range of different magazines ( The Beasts That Hide From Man and Mirabilis ); two books on general mysteries that were published by Carlton, with the second being a direct sequel to the first ( The Unexplained and Mysteries of Planet Earth ); and a trilogy on the subject of new and rediscovered animals ( The Lost Ark , followed by The New Zoo , and then The Encyclopaedia of New and RediscoveredAnimals ).

In addition, there are advanced plans afoot to publish a new, retitled edition of In Search of Prehistoric Survivors ; and also an expanded edition of my poetry volume Star Steeds and Other Dreams (as well as a downloadable spoken version of the original edition).

My trilogy of books on the subject of new and rediscovered animals (© Dr Karl Shuker)

My trilogy of books on the subject of new and rediscovered animals (© Dr Karl Shuker) Meanwhile, my second trilogy of books is now complete, with the publication of The Menagerie of Marvels , whose subtitle, A Third Compendium of Extraordinary Animals, reveals that it is volume #3 in my series dealing with extraordinary animals from both cryptozoology and mainstream zoology. Its two predecessors were Extraordinary Animals Worldwide and Extraordinary Animals Revisited . But what can you expect to find inside it? Well…

Welcome one and all to my Menagerie of Marvels! Where else would you encounter venomous bis-cobra lizards from India and a never-before-documented flying dragon-lizard from Zimbabwe, minuscule fairy armadillos and clamorous go-away birds, genuine roc feathers and a veritable werewolf paw, whale-headed pseudo-pterodactyls and hammer-headed lightning birds, a park of monsters in Italy and mystery beasts in the Vatican, beech martens in Britain and winged toads in France, an invisible catfish and a dicephalous kestrel, the cryptic comadreja and a controversial Caribbean racoon, reverse mermaids and the music of Ogopogo, Africa's missing marmot and Vespucci's vanished mega-rat, earth hounds, vampire shrews, moonrats, nandinias and Nandi bears, undiscovered ajolotes, bemusing bristle-heads, monumental mammoths, gorilla-sized man-eating baboons and giant rhinoceros-eating terror birds, some fishy lake monsters and duplicitous sea serpents, Rift Valley mystery reptiles, vermiform rock-slicing laser gazers, and so much more too, all within the scenic yet comfortingly-secure confines of a single book?

The Menagerie of Marvels can be purchased on Amazon (click here for direct links to it on the UK and on the USA sites), and there is also a special offer on it if purchased directly from its publisher, CFZ Press (click here ). It can also be ordered through all good online and physical bookstores.

So, I hope and trust that you will enjoy your visit to my menagerie, and please do return whenever you wish – its unique collection of extraordinary zoological esoterica and inexplicabilia will always be here to mystify and mesmerise you anew. You have only to step inside...if you dare!

My trilogy of books on extraordinary animals from zoology and cryptozoology (© Dr Karl Shuker)

My trilogy of books on extraordinary animals from zoology and cryptozoology (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Published on November 22, 2014 10:41

November 21, 2014

FLYING TOADS AND FLYING GURNARDS

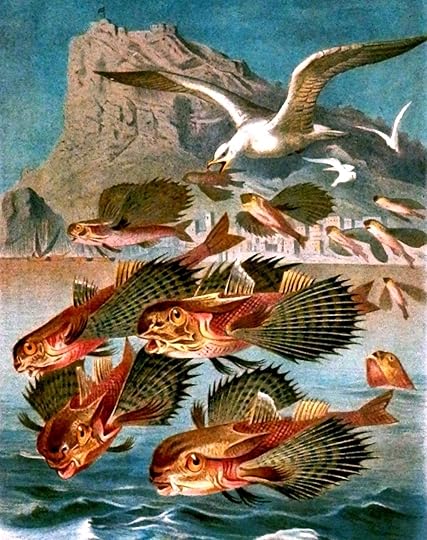

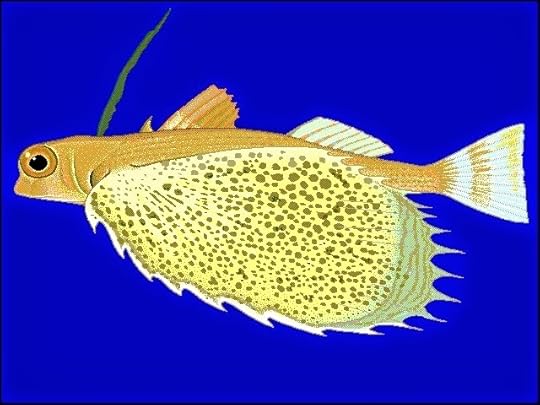

A flying gurnard, depicted in Marcus Bloch's 12-vol Encyclopedia of Fishes, 1782-95; note its toad-like profile

A flying gurnard, depicted in Marcus Bloch's 12-vol Encyclopedia of Fishes, 1782-95; note its toad-like profileIn my book From Flying Toads To Snakes With Wings (1997), the flying toad in question that I chronicled was the llamhigyn y dwr or Welsh water leaper. At that time, it was popularly assumed to be an obscure yet bona fide legendary creature from traditional Welsh folklore. However, I subsequently learnt that it was almost certainly a modern-day hoax invented during the early 1800s by an inveterate, infamous spinner of yarns and other tall tales called Han Owen, as exposed by CFZ researcher and native Welshman Oll Lewis.

My Flying Toads book alongside my very own flying toad! (© Dr Karl Shuker)

My Flying Toads book alongside my very own flying toad! (© Dr Karl Shuker)In later years, conversely, as documented and assessed within an entire chapter devoted to them in my newly-published book The Menagerie of Marvels: A Third Compendium of Extraordinary Animals (CFZ Press: Bideford, 2014), I uncovered and received a number of reports featuring mystifying but seemingly genuine creatures variously likened to winged toads, flying toads, or flying frogs that had been reported from the U.K., France, and the Far East, yet which were decidedly different from the famous flying or (more accurately) gliding frogs Rhacophorusspp. of southeast Asia (which are wingless but after leaping from trees can glide through the air for short periods by virtue of their toes' enlarged interdigital webbing membranes acting as mini-parachutes).

A real-life flying frog in gliding mode, as depicted on the cover of the Czech edition of my book

From Flying Toads To Snakes With Wings

(© Dr Karl Shuker)

A real-life flying frog in gliding mode, as depicted on the cover of the Czech edition of my book

From Flying Toads To Snakes With Wings

(© Dr Karl Shuker)So bizarre in form are these creatures that they remain unidentified, decades or even centuries after they were first reported. To read about them, check out my new book here .

My Balinese flying toad, carved from wood and brightly painted (© Dr Karl Shuker)

My Balinese flying toad, carved from wood and brightly painted (© Dr Karl Shuker) Just a few days after I sent my book's final version to the publishers and thence to the printers for publication, I received from English bibliographical crypto-sleuth Richard Muirhead (thanks, Richard!) a fascinating newspaper report concerning what was described in it as a flying toad, but this time from the USA. Sadly, the downside was that it was too late for me to include this report in my book, but the upside was that after reading it I felt confident that unlike those in my book, this was one flying toad whose identity I could definitely lay bare.

Here is the text (there were no images) of the report in question, which had appeared on 28 August 1869 in an English newspaper called the Grantham Journal:

"An American paper reports the capture of a flying toad at Cape Henry [on Virginia's Atlantic shore] a few days ago, and says it is now in Washington. It is of most singular conformation and of beautiful variated hues, measuring about six inches in length, with a perfectly flat, bony back, eyes wide spaced and in the centre of a…mouth, and fins as large as wings about the centre of the body on each side."

The reference to the specimen being "now in Washington" suggests that following its capture it was sent to the Smithsonian Institution, so that would seem to be the most promising place to contact in the hope of uncovering further information concerning this strange creature. Having said that, however, I feel sure that we can ascertain its identity with a high degree of probability just from the report alone. For although the above account may sound truly bizarre, it is in fact an accurate description of an extremely distinctive and quite spectacular species of small marine fish – Dactylopterus volitans, the so-called flying gurnard.

Atlantic flying gurnard Dactylopterus volitans with its beautiful wing-like pectoral fins outstretched (© Beckmannjan/Wikipedia GFDL)

Atlantic flying gurnard Dactylopterus volitans with its beautiful wing-like pectoral fins outstretched (© Beckmannjan/Wikipedia GFDL)Flying gurnards, of which there are several species, are exceptionally difficult to classify. Measuring up to 1 ft long, the Atlantic flying gurnard Dactylopterus volitans(whose distribution along the USA's eastern coast includes Virginia, where the so-called flying toad was captured) and the comparably-sized starry flying gurnard Dactyloptena (=Daicocus) peterseni from the Indo-Pacific are among the most familiar representatives of these curious fishes. Over the course of time, they have been variously categorised with the true gurnards, the sea-robins, and the sea-horses, but are nowadays generally housed in their own suborder within the taxonomic order Scorpaeniformes, or even within an order entirely to themselves. Apart from Dactylopterus volitans, flying gurnards are mostly of Indo-Pacific distribution, and are benthic (bottom-dwelling) species.

Note the unquestionably toad-like appearance of the flying gurnard's head and face (© Marco Chang/Flickr)

Note the unquestionably toad-like appearance of the flying gurnard's head and face (© Marco Chang/Flickr)Superficially similar to true gurnards but distinguished from them anatomically by subtle differences in the arrangement of their head bones and the spines of their pectoral fins, flying gurnards are characterised by their large, bulky heads encased in hard bone and surprisingly toad-like in appearance when viewed both in profile and face-on; their brightly-coloured, box-shaped bodies, dappled with multi-hued spots; and, above all else, by the enormously enlarged pectoral fins of the adults, expanded like giant, heavily-ribbed fans or paired wings.

Compare this description with that of the 'flying toad' of Cape Henry and it seems evident that they are referring to one and the same creature.

But this is not the only mystery of natural history to feature the flying gurnards. Even more perplexing is whether, in spite of their longstanding 'flying' epithet, these wing-finned fishes ever actually do become airborne.

Flying gurnards, depicted airborne in a chromolithograph from 1893 – but can they really glide through the air?

Flying gurnards, depicted airborne in a chromolithograph from 1893 – but can they really glide through the air?Back in 1991, I investigated this curious riddle in the first of my trilogy of extraordinary animals books – Extraordinary Animals Worldwide ; and returned to it 16 years later in my trilogy's second book – Extraordinary Animals Revisited (2007). Here is what I wrote and revealed in that latter book:

Records dating back as far as Greek and Roman times tell of how these attractive fishes are able to launch themselves out of the water and glide over the surface for a notable distance, just like the better known ‘flying fishes’ (Exocoetus spp.), before plunging back down into the sea again, and even compared their gliding with that of swallows. According to early authorities such as Salvianus, Belon, and Rondelet, the reason for this behaviour was to escape predators in the water (even though by leaping out of it they surely exposed themselves to the danger of being swooped upon by gulls and other seabirds).

A true flying fish taking off (public domain)

A true flying fish taking off (public domain) Yet whatever the reason for gliding, for a long time there seemed no reason to doubt that they did glide. There are numerous reports on record from schooners and other ocean-going vessels, recounting the impressive sight of whole schools of these colourful sea creatures suddenly breaking through the surface of the sea and gliding for up to 300 ft or more on their varicoloured outstretched pectorals, before sinking back beneath the waves, only to be replaced by a second school, and then by a third, and so on, in a breathtaking display of piscean aerobatics.

One of the chief reasons for subsequent scepticism arose from a grave error by naturalist H.N. Moseley and fellow researchers aboard the late 19th Century research vessel Challenger. Their reports testified to the frequent occurrence of schools of flying gurnards rising up out of the water and gliding past on wing-like pectorals; tragically, however, it was later shown that they had misidentified these fishes. Instead of flying gurnards, they had been the true Exocoetus flying fishes! Naturally, this did not help the flying gurnard’s case. Since then, the general consensus has been that flying gurnards are too heavy and cumbersome even to lift themselves up out of the water, much less to soar above it. Not everyone, however, is convinced by this.

Drawing of an Oriental flying gurnard Dactyloptena orientalis (public domain)