Karl Shuker's Blog, page 44

July 19, 2014

PUMAPARDS AND LEPUMAS – UNUSUAL FELINE HYBRIDS OF HAGENBECK

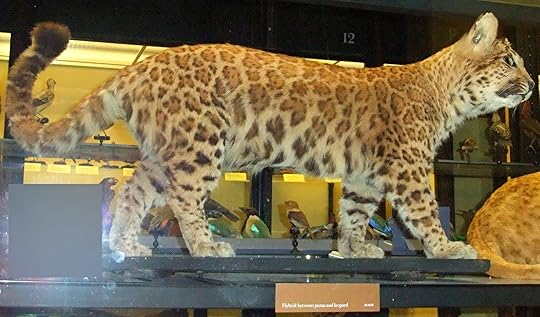

Carl Hagenbeck's terrier-reared pumapard preserved as a taxiderm specimen at Tring Natural History Museum (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Carl Hagenbeck's terrier-reared pumapard preserved as a taxiderm specimen at Tring Natural History Museum (© Dr Karl Shuker)Although it can often equal or even exceed the leopard Panthera pardus in overall size, the puma Puma concolor is not a 'big cat' in the strict scientific sense - its throat structure, for example, is quite different from that of true big cats (i.e. belonging to the genus Panthera). It is particularly surprising, therefore, that successful matings between pumas and some of the Pantheraspecies have occurred - the resulting hybrids thereby being intergeneric rather than merely interspecific.

Probably the most famous of these were the several litters of puma x leopard hybrids bred in 1898 at German animal dealer Carl Hagenbeck's Tierpark (which moved premises to Hamburg's Stellingen quarter in 1907). One of these was a pumapard (male puma x leopardess hybrid) raised by a fox terrier bitch that was displayed at Hagenbeck's Tierpark during the first decade of the 20th Century. This specimen resembled a puma in overall form but was noticeably smaller in size than either of its progenitor species and was marked with pronounced rosettes and blotches. It also had a very long tail.

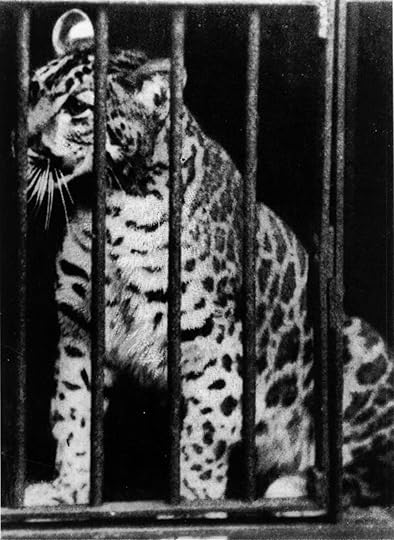

The familiar cropped version of the only known photograph taken of Hagenbeck's terrier-reared pumapard when alive (public domain)

The familiar cropped version of the only known photograph taken of Hagenbeck's terrier-reared pumapard when alive (public domain)One of Hagenbeck's pumapards is preserved as a taxiderm specimen at Tring's Natural History Museum in Hertfordshire (as seen by me when I visited this wonderful museum as a birthday treat in December 2012), which was originally the personal zoological museum of Lord Walter Rothschild. There is some confusion in various online accounts as to whether this specimen, small in size, is one and the same as Hagenbeck's pumapard reared by a fox terrier. However, in The Living Animals of the World, a two-volume multi-contributor animal encyclopedia from 1901, the above photograph of the terrier-reared pumapard was published with a caption stating that the animal was now dead: "...and may be seen stuffed in Mr. Rothschild's Museum at Tring" - which would seem to confirm that they are indeed one and the same individual.

Hagenbeck's terrier-reared pumapard preserved at Tring (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Hagenbeck's terrier-reared pumapard preserved at Tring (© Dr Karl Shuker)A comparable cat, yet derived from the reciprocal cross (male leopard x female puma), thereby making it a lepuma, was purchased from Hagenbeck by Berlin Zoo in 1898, and was said at the time by the zoo's director, German zoologist Dr Ludwig Heck, to resemble "a little grey puma with large brown rosettes". Documenting this same animal in 1968, German cat expert Dr Helmut Hemmer described it as being fairly small with somewhat faded rosettes present upon a background pelage colour resembling that of a puma. Puma x leopard hybrids obtained by artificial insemination are also on record.

A photocopy of the original yet rarely-seen uncropped version of the only known photo of Hagenbeck's terrier-reared pumapard taken when alive, revealing that it was photographed whilst sitting alongside its fox terrier foster-mother (public domain)

A photocopy of the original yet rarely-seen uncropped version of the only known photo of Hagenbeck's terrier-reared pumapard taken when alive, revealing that it was photographed whilst sitting alongside its fox terrier foster-mother (public domain)This ShukerNature blog article was excerpted from my book Cats of Magic, Mythology, and Mystery (CFZ Press: Bideford, 2012), which contains further details regarding many fascinating examples of feline hybrids – check it out!

Published on July 19, 2014 16:16

July 18, 2014

THE CLIFDEN NONPAREIL – BEWITCHED BY NABOKOV'S ELUSIVE BLUE UNDERWING

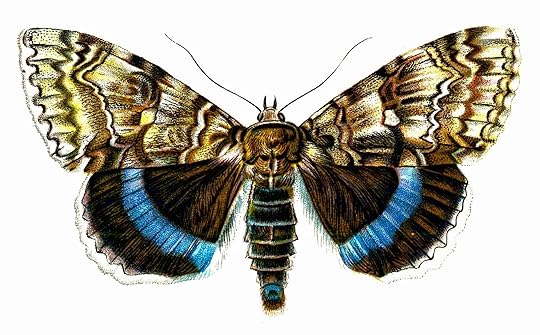

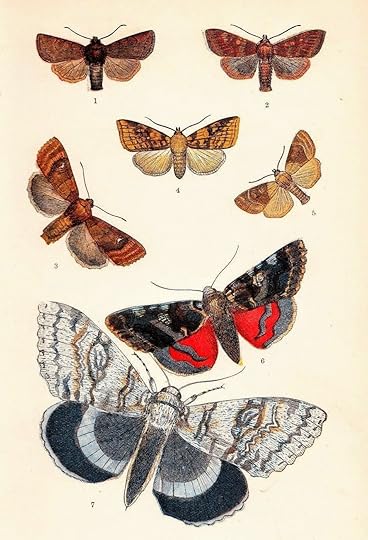

Suitably named – the truly unparalleled, peerless clifden nonpareil, gorgeously portrayed in Dr F. Nemos's book Europas bekannteste Schmetterlinge. Beschreibung der wichtigsten Arten und Anleitung zur Kenntnis und zum Sammeln der Schmetterlinge und Raupen (c.1895)

Suitably named – the truly unparalleled, peerless clifden nonpareil, gorgeously portrayed in Dr F. Nemos's book Europas bekannteste Schmetterlinge. Beschreibung der wichtigsten Arten und Anleitung zur Kenntnis und zum Sammeln der Schmetterlinge und Raupen (c.1895)In a previous ShukerNature blog article (click here ), I reminisced about my lifelong ambition (finally fulfilled after 48 years of ongoing frustration!) to see the bird above all others that had bewitched me from my earliest days – that cerise-plumed, butterfly-winged wonder known as the hoopoe, which is a rare but annual visitor to Great Britain.

So too is another species – one that to me is the hoopoe of the moth world, because the thought of seeing this spectacular creature one day fills me with just as much enthusiasm and passion as I felt for so long and so earnestly in relation to the hoopoe. Yet whereas the latter is finally on my list of observed species, its equally charismatic lepidopteran counterpart remains resolutely unseen, still unencountered by me more than 54 years on from when I made my debut on the planet that I share with it.

Clifden nonpareil depicted upon a postage stamp issued in 1974 by Hungary

Clifden nonpareil depicted upon a postage stamp issued in 1974 by HungarySo what is this peerless, unparalleled species? None other than the fittingly-named clifden nonpareil Catocala fraxini ('nonpareil' translates from the French as 'without equal'). One of Britain's largest species of moth, it is also known, again appropriately albeit somewhat less romantically, as the blue underwing.

Indeed, so noteworthy is this moth's appearance that it even attracted the attention of eminent Russian novelist Vladimir Nabokov. Well known for his passion for Lepidoptera, he immortalised the clifden nonpareil in his novel The Gift (1938, English translation 1963): "Your blue stripe, Catocalid, shows from under its gray lid".

Clifden nonpareil (© Harald Süpfle/Wikipedia Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0)

Clifden nonpareil (© Harald Süpfle/Wikipedia Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0)This celebrated species belongs to the taxonomic family Noctuidae, the owlet moths, which is the largest family of moths, is of worldwide distribution, and contains over 35,000 species. Within this family is the genus Catocala, containing over 250 species, native to Eurasia and North America, which are popularly termed underwings or underwing moths (Catocalais Greek for 'beautiful hind ones'). This name refers to the usually bright stripes of colour present on the upper side of their hindwings. At rest, an underwing moth's hindwings are concealed beneath its larger but very drab, grey-brown, cryptically-patterned forewings, allowing it to remain hidden from predators when resting in the open on the trunks of trees, etc. Should its presence be detected, however, in order to startle the predator momentarily and thus provide valuable escape time the moth will flash its brightly-coloured hindwings, abruptly revealing their colours. Due to the semi-circular shape of the stripes, moreover, it has been speculated that they may look like owl eyes to smaller birds, which would therefore frighten them away, saving the moth.

These stripes occur in a wide range of colours, varying between species, and many Catocala species are named accordingly. Thus there are red underwings, crimson underwings, rosy underwings, scarlet underwings, pink underwings, and so forth. Moreover, certain members of related genera that possess comparable hindwings are also referred to as underwings, such as the copper underwings Amphipyra spp., yellow underwings Noctua spp., and the brown underwing Minucia lunaris. In addition, there are two species of orange underwing Archlearis spp., but these belong to a separate taxonomic family, Geometridae.

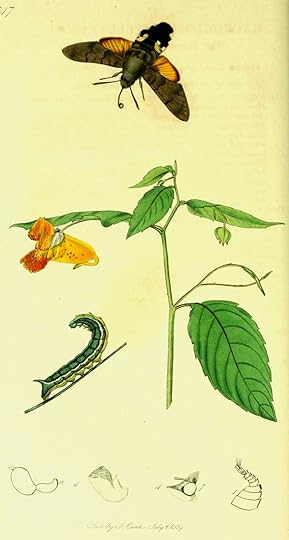

A red underwing Catocala nupta(top) and a clifden nonpareil (bottom), pictured in The Natural History of British Moths (1836), by J. Duncan

A red underwing Catocala nupta(top) and a clifden nonpareil (bottom), pictured in The Natural History of British Moths (1836), by J. DuncanYet despite the difference in specific colours, these many species' hindwing stripes all occur in the red portion of the colour spectrum – all except the stripes of one very singular, special species, that is. Lone among all underwings, the stripes of the clifden nonpareil are blue, and not just some nondescript grey-blue shade either, but instead a bright, truly spectacular blue, which must be genuinely dazzling if suddenly flashed in the face of an inquisitive, too-close-for-comfort avian observer.

Blue has always been far and away my all-time favourite colour – so much so in fact that I sometimes wonder whether my wardrobe would have been so plentifully packed with Levis and other jeans, not to mention trucker jackets and shirts, had the predominant dye for denim been anything other than blue! Hence it was inevitable that a blue underwing – and especially when it is the only blue underwing – would attract my enduring interest and attention once I'd learnt of such an exotic creature's existence, and thus has it proved.

Clifden nonpareil in grass (public domain)

Clifden nonpareil in grass (public domain)Moreover, boasting a 4-inch wingspan the clifden nonpareil is set apart from all other underwings not only by its blue hindwing stripes but also by its very large size – indeed, it is the world's largest species of Catocala underwing. It was scientifically named by none other than Linnaeus, in 1758, who dubbed it Phalaena fraxini (noting its sometime occurrence on ash trees, Fraxinus spp.) but it was subsequently rehoused in the genus Catocala after the latter was coined in 1802 by German entomologist Franz von Paula Schrank. It has a wide Old World distribution, being found as a resident in deciduous woodlands (especially near water) of northern and central Europe (and as a migrant in eastern and southern Europe), as well as in northern Asia, and in temperate eastern Asia as far as Japan. However, it is its famed rarity in Britain that has earned it its reputation as a near-legendary species - one that was prized above all others by moth collectors during the Victorian era.

The first published reference to the clifden nonpareil's occurrence in Britain was by Benjamin Wilkes in his book The English Moths and Butterflies (1749), in which he recorded a specimen lately collected by a Mr Davenport on an ash tree near Clifden (now known as Cliveden) in Buckinghamshire – the location which, together with its unrivalled beauty, earned this species its common name. However, it had been known in Britain since at least 1740 – the year in which a specimen now in the Dale Collection within Oxford's Hope Museum was collected in Dorset. Since then, usually single specimens have been reported in a number of English counties spasmodically up until the 1940s and 1950s, during which period sightings increased as its range temporarily expanded due to favourable climatic conditions, even giving brief hope that this evanescent species had permanently established itself as a resident in Kent and the Norfolk Broads. Sadly, however, that hope was not fulfilled, because sightings fell again following the return of less favourable climate by the early 1960s, and it once more became merely an irregular immigrant.

Clifden nonpareil – extracted from Duncan's above-reproduced 1836 colour print

Clifden nonpareil – extracted from Duncan's above-reproduced 1836 colour printFavouring the aspen as its larval foodplant (though also selecting other poplar species if aspen are not present, and sometimes found on ash trees too), the clifden nonpareil is most commonly sighted in September, particularly in southern and southeastern England. In recent years, however, there have been well-publicised records from the Westcountry counties too (one specimen turned up at Cornwall's Lost Gardens of Heligan in autumn 2010), and there is even a faint possibility that small colonies are establishing themselves in Suffolk. The recolonisation of southern England by this exquisite species would be a wonderful occurrence, so we can but hope that prevailing climatic conditions continue to encourage this most welcome trend. And who knows – if this does occur, one day the clifden nonpareil might expand its range even further, taking in my home county of the West Midlands. In 1872, there was a record from the neighbouring county of Shropshire, plus there are several 19th-Century records from northern England, and even Scotland and Ireland too, so it was clearly not a confirmed southerner back then.

What a marvellous, magical experience it would be if, finally, some day in the not-too-distant future I could encounter a large grey moth that suddenly flashed its hindwings at me to reveal a dazzling stripe of bright blue. For me, such an event would definitely be peerless, truly unparalleled – just like the clifden nonpareil itself.

19th-Century colour plate featuring a clifden nonpareil

19th-Century colour plate featuring a clifden nonpareil

Published on July 18, 2014 18:03

July 17, 2014

NURE-ONNA AND USHI-ONI – TWIN TERRORS FROM THE LAND OF THE YOKAI

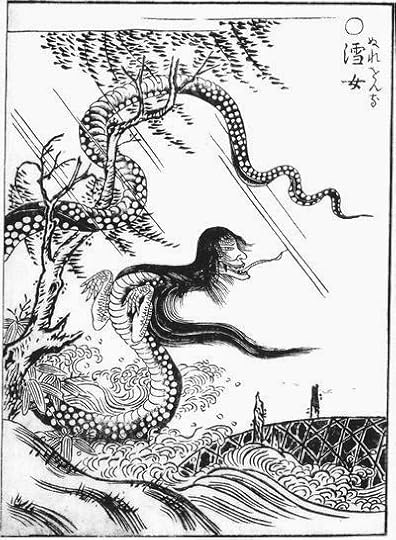

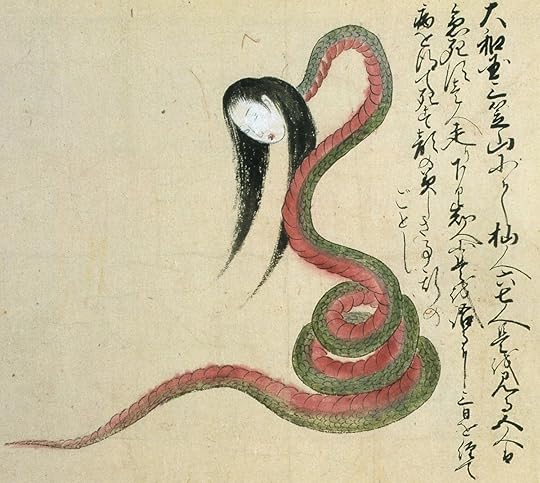

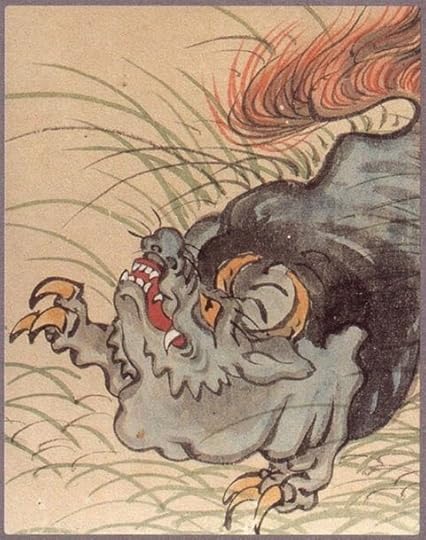

Nure-onna, by Sawaki Suushi, 1737

Nure-onna, by Sawaki Suushi, 1737 Imagine a land infested with rapacious shape-shifting spider-maidens, hideous blood-sucking hags with razor-sharp talons, gigantic fire-breathing roosters, green-skinned rubbery ghost-turtles, enormous disembodied skyborne heads foretelling thunderstorms, and innumerable other monstrosities of mayhem. For what is, geographically-speaking, a relatively small, insular nation, Japan has an extraordinarily diverse pantheon of traditional mythological monsters, many of which are known collectively as yokai. These exist in every form imaginable – and, in some cases, wholly unimaginable! – but are united in their frequently nightmarish appearance and ferocious behaviour.

Think of every conceivable way in which a human can be captured, torn apart, and bloodily devoured, and the chances are that there is a yokai designed specifically for that role. Clearly, ancient Japanese culture had an inordinately febrile collective imagination (either that or there was something very strange in the sake!), but rarely has this been more effectively demonstrated than in the folklore appertaining to two of the yokai clan’s most fiendish members – the nure-onna and the ushi-oni. And to make matters even worse, whereas even a single yokai is usually more than sufficiently horrifying for all but the bravest of persons to confront, the nure-onna and the ushi-oni often join forces to create a terrifying partnership designed specifically to ensnare and engulf anyone unfortunate enough to chance upon these foul entities.

Now, drawing upon traditional yokai lore, here is how I envisage such a fearful encounter may unfold. So, be warned – if you have a loathing for serpents, a horror of spiders, or, even worse, a terror of both, this is definitely not the place to be!

It was a warm summer’s afternoon when the young fisherman took his new bride for a walk along the coastline of Shimane Prefec-ture in western Japan. Having lived her entire life in the city, where they’d met and fallen instantly in love with one another during his very first visit there just a few months earlier, she had never before even seen the sea, and was delighting in the gentle roar of its distant waves, the raucous cries of the gulls overhead, and the soft caressing foam that lapped around her feet as she stepped over stones and seashells at the very edge of its fluid turquoise domain.

Her husband, walking behind her, smiled at her laughter and child-like enjoyment of this totally new experience, and even the clouds that had threatened earlier to overshadow their afternoon had drifted apart, welcoming the golden sunlight that flooded the scene and danced in dazzling glee upon the sea’s shimmering surface. It was an idyllic scene – too idyllic, perhaps.

Rounding a corner, the two walkers were startled to see what looked like a young naked woman, submerged from her waist down, leaning upon a rocky outcrop just ahead of them as she combed with great care and attention her long, luxuriant hair that flowed all about her, rippling in the cool sea breeze, and as black as ebony. Again and again she combed these dark locks, until they gleamed like rivulets of Night. And next to her, placed precariously upon one of the rocks, was a bundle, wrapped roughly in rags – but which looked suspiciously as if it may contain a baby.

Yet the young woman paid no attention to it whatsoever, devoting herself entirely to the obsessive combing of her sable tresses. The fisherman’s bride was fascinated by this incongruous scene, so much so that she failed to see the expression of absolute horror that had frozen her new husband’s face into a silent, rigid mask. Indeed, so transfixed was he by what he was seeing that he was unable even to scream out to his bride as she moved closer to the young woman.

Suddenly, the woman looked up, and saw the bride approaching. Concerned that the bundle, which she felt sure was indeed a baby, may topple off the rock and fall into the sea, the bride was walking towards it. As soon as she realised this, the woman picked up the bundle, held it close to her breasts for a moment, and then, gazing directly at the bride and smiling, offered it to her in outstretched arms.

Nure-onna, by Toriyama Sekien 1781

Nure-onna, by Toriyama Sekien 1781 Finding his voice at last, the petrified young fisherman opened his mouth and let out a single desperate shriek of warning – but it was too late! His bride, smiling back at the strange woman with the long black hair, had stretched out her own arms and had taken the bundle in them, gently and welcomingly.

She bent her head down, to look at the face of the baby that she expected to see looking back out at her from the humble bundle of rags that she was cradling – but her frantic husband knew only too well what she would see, and it wouldn’t be a baby.

Raised in a small coastal fishing village nearby, he knew all about the horrors that lurked in the ocean depths and occasionally came ashore – the evil maritime yokai that sometimes assumed human form to tempt and terrorise the mortals who shared their coastal domain. Varied indeed were their forms, but few were more horrific, and deadly, than the nure-onna. As lethal as an iceberg, this malevolent entity further resembled one inasmuch as most of her immense form remained hidden beneath the surface of the sea, with only a small proportion appearing above it - which invariably assumed the innocent guise of a coy young woman combing her long inky-black hair, with a bundle of rags placed beside her.

And if anyone should be unfortunate enough to encounter her, and to approach her little bundle, the woman would offer it – but never, never, should it be accepted!

If only he could have put this wisdom to good use, but his unsuspecting bride had already taken the bundle in her arms, and even now, as he watched, he saw her head jerk back in shock at what she had seen concealed amid the rags.

There was no baby! True, the rags had been artfully arranged to give the impression that they contained an infant, but what they really contained was nothing more than a very large, heavy rock!

Startled, and totally perplexed, the bride looked at the young woman, and as she did the woman grinned back at her, a malign, vicious grin that exposed a formidable array of sharp teeth, including a pair of long curved fangs that dripped with amber venom. At the same time, the waves behind her began to froth and surge, as if something enormous had risen from their dark, sequestered depths and was about to break forth through their mirrored surface – which is precisely what was about to happen.

Suddenly, a series of enormous scaly coils, seemingly limitless in length, appeared, thrashing wildly as they sent great showers of spume and seawater cascading in all directions. And as the bride gazed at this blood-chilling scene, the young woman began to rise up in front of her, revealing that she was only semi-human. Below the waist she was entirely reptilian, or, to be more specific, serpentine - for the remainder of her form consisted of those vast ophidian coils, which in total measured at least 300 metres, stretching back as far as the eye could see as they undulated madly in a ceaseless frenzy above the whip-lashed sea surface.

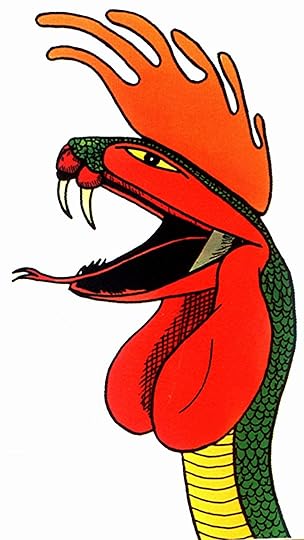

Nure-onna (© Gojin Ishihara, 1972)

Nure-onna (© Gojin Ishihara, 1972)There could be no doubt – just as the fisherman had feared, the marine demon confronting his doomed bride was none other than a nure-onna, the gargantuan, merciless snake-woman of the sea. Surely, then, there could be no escape for his beloved, or, indeed, for himself. For as if the scene facing them were not already horrifying enough, the fisherman knew that worse was still to come – because the nure-onna rarely appeared alone. Waiting to participate in its inevitable feast of human flesh was, assuredly, an equally voracious sea-monster – the ushi-oni.

As soon as his bride attempted to flee, by hurling the rag-enveloped rock away or even directly at the snake-woman, she would feel as heavy as the rock itself, rooted to the spot, unable to take even a single step away from the loathsome humanoid serpent rearing up before her. Then this monstrous creature would flick its huge tail forward and coil it around his helpless bride’s paralysed body, lifting her up to its open jaws, out of which its long scarlet tongue would emerge, wrap itself tightly about her in an unyielding vice-like grip, and proceed to drain every last drop of blood from her body until she was nothing more than a shrivelled, etiolated corpse.

But instead, something extraordinary happened. The fisherman’s bride had no knowledge of the sea, its traditions, and the countless monsters that it concealed, but she had not only the innate maternal empathy that all women possess but also the cool-headed, quick-witted confidence that a life spent in the bustling heart of a big city had readily bestowed upon her. Not easily frightened, and reared upon science and logic rather than folklore and superstition, she was well-equipped to deal rationally even with extreme situations far outside her normal limits of experience. Consequently, intuition and innovation now united in the briefest tremor of time to offer her a single chance of escape – if she was brave enough to take it.

The nure-onna’s huge tail had already lifted itself out of the raging waters of the sea and was surging shoreward – within just a few seconds it would be wrapping itself around its victim’s body. But even as it moved forward, so too did the bride’s arms, as, with all due care and reverence, bowing her head respectfully towards the colossal creature - and in spite of her great fear - she offered the wrapped rock back to it.

The nure-onna’s eyes, which only moments before had glowed in unholy, exultant joy, now betrayed visible flickers of surprise and even bewilderment as they glared down upon this slight human form giving back to it as a tribute in unspoken supplication its pseudo-child, still wrapped in its rags, and tenderly handled with evident sincerity.

Never before had this happened! In what seemed like the passing of a single heartbeat that yet spanned eternity, the nure-onna reflected on what course to take, as the bride remained with bowed head before its upraised form, and her husband stood a little way behind, as still and silent as a statue, frightened that even the faintest movement or murmur from him might break this extraordinary spell and bring instant death upon both of them.

And then, slowly, almost hesitantly, the nure-onna stretched out its arms, and took the bundle from those of the bride, and, as before, held it for a moment to its breasts. Its colossal tail, which was still upraised, and by now almost touching the bride - who remained standing with head bowed before this gigantic sea-demon - dropped back into the sea, sending a mighty wave crashing about the shallows, as it sank down beneath the surface. And as the tail sank, so too did the nure-onna’s huge body coils, vanishing one by one back down into the cavernous lightless unknown kingdom far below the sea’s upper levels.

Soon, nothing remained above the surface but the human portion of the nure-onna, who looked once more at the bride and also, momentarily, at her husband, before it too disappeared beneath the waves. Not a trace remained now of the gargantuan monster that only moments before had filled the shore and had stretched back out as far as the very horizon itself.

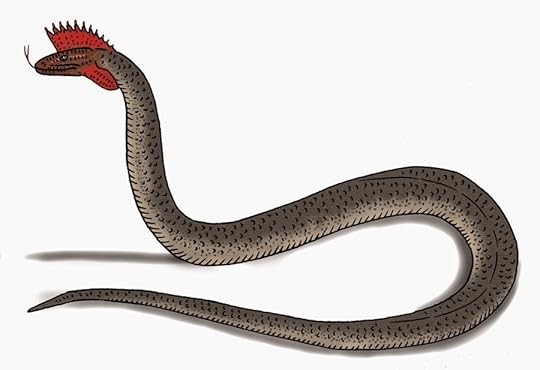

Snake-woman from Mt Mikasa, resembling the nure-onna, depicted in the Kaikidan Ekotoba (a mid-1800s hand-painted scroll profiling 33 Japanese monsters and human oddities)

Snake-woman from Mt Mikasa, resembling the nure-onna, depicted in the Kaikidan Ekotoba (a mid-1800s hand-painted scroll profiling 33 Japanese monsters and human oddities)As if released from a spell of petrification, the young bride began shaking with hitherto-suppressed fear, and her husband ran up to her, and held her within his arms. He wanted to tell her so much how it was all over now, that they were safe, and that everything would be fine – but he knew with dread certainty that it was far from all over, that they were anything but safe, and that the prospect of everything being fine was slim in the extreme.

And even as these dark thoughts soared through his mind on shadowy wings of panic, the sea before them began to surge again. The nure-onna? Surely it had not returned? The bride opened her mouth to scream, but at the same moment her husband dragged her ashore, and began to run back from its edge with her, pulling her with him as he raced across the pebbly beach, moving as far away from the shoreline as possible. But then came the noise that he had hoped never to hear – an ear-splitting bellow of rage that sounded like the loudest roar ever voiced by the biggest, most ferocious bull that ever lived. And in a sense, that is exactly what it was – except that the bull in question was no ordinary specimen.

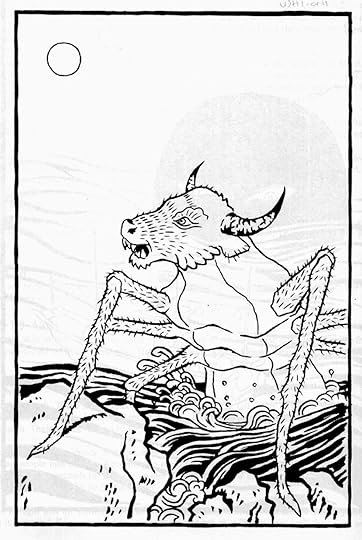

When they heard this terrifying noise, the two young people turned round to look back – and saw a creature so horrific that even the nure-onna suddenly seemed a little less frightening than it had previously done! Standing on the very edge of the shore, still wet from having just emerged from the sea, was a monstrous beast that the fisherman immediately recognised as an ushi-oni.

Its massive head was like that of a huge black bull, armed with a pair of mighty horns, but it also had flaming crimson eyes, flaring nostrils that spewed forth dark, caliginous clouds of fiery smoke, and open jaws that betrayed the presence of numerous sharp, unequivocally carnivorous teeth – far removed from the cud-chewing molars of normal cattle. Yet if its head seemed bizarre, the rest of this sea-spawned nightmare was positively surrealistic – for eschewing the typical four-limbed bovine form that might have been expected to complement its head, it instead sported the hideous eight-limbed body of a colossal spider!

Ushi-oni, by Sawaki Suushi, 1737

Ushi-oni, by Sawaki Suushi, 1737Although the ushi-oni was paying close attention to the fisherman and his bride, it also seemed somewhat distracted, its head periodically swinging from side to side as if searching for something. The fisherman realised that it was looking for its fiendish collaborator, the nure-onna, puzzled that it was not here, ready to help seize these puny humans cowering on the beach.

Seeing the monster’s hesitation, the fisherman grabbed his bride’s hand and raced off along the way they had come earlier that afternoon, towards the cliff face and onward to the passage that led back through the steep rocks to their village. But their sudden flight alerted the ushi-oni, who scuttled after them in deadly pursuit, the absent nure-onna now forgotten as it threw back its head and roared again in bellicose fury.

Unaccustomed to running at speed across the uneven pebbles, slippery rocks, and treacherous stones half-hidden beneath the shifting sands, the fisherman’s bride slipped and fell several times, and each time that he stopped to pick her up, the ushi-oni gained ground. Desperate to elude it, the fisherman abruptly changed course, cutting back on his previous route in the hope that they could escape through some rocky crevice large enough for he and his bride to slip through but too small to permit the gargantuan ushi-oni to do the same.

But even as they ran on, his bride was tiring, physically weary from their prolonged flight and mentally exhausted from her earlier terrifying ordeal with the nure-onna. Very soon she would be unable to flee any further, the ushi-oni would catch up with them, and then...

Frantically seeking any possible escape route, the fisherman suddenly spotted a v-shaped high-walled passage opening up ahead between the rocks. Its widest point was its entrance, so if, once inside, they could run along its corridor and exit at its furthest, narrowest end, they would leave the ushi-oni far behind, because the passage’s exit, although hidden in shadow at this distance, would undoubtedly be too small and tight for the ushi-oni to force its way through. With relief buoying their flagging spirits, the two young people ran directly towards the passage, entering its shadowy, narrowing corridor just moments before the ushi-oni arrived behind them.

They ran down the corridor at full pace, towards its furthest end, looking for an opening amid the shadows that would grant them a secure escape from the bloodthirsty spider-bull. Then, a dark aggregation of clouds that had been eclipsing much of the late afternoon’s sunlight finally drew back, enabling the sun to send bright shafts of light down upon the cliff face and into the passage where the fisherman and his bride were anxiously seeking the exit.

Ushi-oni (© Anthony Wallis)

Ushi-oni (© Anthony Wallis) And as it did so, they looked at each other in horror. With the shadows obliterated, they could see only too clearly that there was no exit there after all – the passage was an unbreachable cul-de-sac of solid rock, whose sheer, steep-sided walls offered no means of escape either. They were trapped! And bearing down upon them was the ushi-oni, blocking the entrance and glaring balefully at its imprisoned prey as it attempted to squeeze its repulsive arachnid body ever closer towards them down the narrowing passage.

Faced with certain, horrific death, the shattered mind of the fisherman’s bride abruptly shut down, and she collapsed unconscious at his feet. But even as he knelt to gather up her prone form, he too knew that it was surely over. The monster was now so near, clawing its way as it strove to force its bloated form down those last few metres separating its salivating jaws from its victims, that the fisherman could feel its sulphurous breath burning his face and taste its acrid fumes choking his throat.

And then he remembered his grandfather and their family’s sword. Like so many others living near the coast, the fisherman’s family was poor, but they owned a few precious, closely-guarded heirlooms, passed down through countless generations. One of these was a beautiful sword, whose hilt was ornately decorated with swirling symbols, and whose gleaming blade was razor-sharp and shone with a bright silver sheen even at night. As a small child, the fisherman had been earnestly informed by his grandfather that this was a magical sword, one that would come to the aid of any family member in dire need of its help. Needless to say, just like any curious child would have done, the fisherman had tried his best to entice the sword to come to him, but it had remained resolutely still. His grandfather had explained that it would only come if the need was urgent enough, but as he grew older the fisherman had suspected that this legend owed more to his grandfather’s renowned story-telling prowess than to any genuine magical ability of the sword.

If only it really had been true! Now, surely, more than at any other time in his life, the fisherman’s need for assistance from his family’s enchanted sword was sufficiently urgent. He pictured its intricate hilt, its flashing, sparkling blade, and his mind cried out to it, beseeching it to save him and his bride from the foul monstrosity whose black maw was already open wide, as it struggled unceasingly to haul itself close enough to engulf them.

It was no use. The fisherman held his still-unconscious bride up against himself, hoping to shield her for as long as possible from the ushi-oni’s voracious jaws. He closed his eyes, and prayed that their death would be swift. Then, without warning, he heard an extraordinary sound – a whining hum that was almost like a wordless song, and which, as it grew ever louder, seemed to be cutting directly through the air towards them.

The fisherman opened his eyes in wonder, and just as he did so, he heard what sounded like a single enormous clap of thunder. At that same instant, he saw the ushi-oni open its jaws even further and let forth a truly ear-splitting, bloodcurdling scream that chilled the fisherman to the bone and resounded inside his head until he was almost deafened by its booming echoes. Then, as he watched in mesmerised terror, he saw the fiery eyes of the ushi-oni grow dim, and close, and he watched its octet of scuttling spider legs shiver and buckle, until they could no longer bear the weight of the monster’s enormous body, collapsing beneath it as it dropped to the ground. It gave out one final groan, and a couple of its trapped limbs twitched a few times - then, silence, and stillness. The ushi-oni’s lifeless head swung down, crashing against the rocky ground. It was dead – their would-be destroyer had, instead, been vanquished itself – but by whom, or what?

Ushi-oni, by Toriyama Sekien, 1781

Ushi-oni, by Toriyama Sekien, 1781 Once he was absolutely certain that the great monster was indeed no more, the fisherman rested his bride’s body gently on the ground, then, gingerly, he stepped around the edge of the fallen ushi-oni’s immense form. And there, buried right up to its richly-ornamented hilt within the creature’s swollen abdomen, was his family’s heirloom sword – the magical sword of his childhood whose power he had, as an adult, scoffed and discounted as a fairy tale – but not any more. Just as his grandfather had always claimed, if the need was sufficiently urgent, it would indeed come to the aid of any family member.

The fisherman leaned closer, grasped the sword’s hilt, and pulled back with all his might, and as he did so, the sword released itself from the ushi-oni’s body, and re-emerged, covered with foul-smelling black blood. Although he was trembling not only with cold but also with fear from all that he and his bride had experienced that day, the fisherman didn’t hesitate to take off his cotton tunic and wipe clean the sword’s blade, until it shone once more in the setting sun of early evening.

Then he walked back to his bride, and as he approached her he could see that she was stirring. He ran to her, placed the sword down, scooped her up in his arms, and kissed her mouth lovingly, feeling his heart leap as she opened her eyes, looked into his face, and smiled.

When she saw the dead ushi-oni lying before them, she jerked back and seemed about to faint again, but her husband comforted her, explained what had happened, and showed her his family’s marvellous sword. She looked at it in wonder, scarcely believing what he had told her, but after he had helped her to her feet, and pointed out the mortal wound that the sword had inflicted upon their seemingly invincible enemy, then she believed, and, like him, gave thanks for the protection afforded them by the sword. Afterwards, holding his bride’s hand in one of his own, and the sword in the other, the fisherman led the way back along the passage’s corridor, now entirely veiled in deep shadows, finally arriving at its wide entrance again, from where they stepped back out onto the beach. From here it was just a fairly short walk to the crevices that did lead through the steep rocks to their village on the other side.

Somehow, inexplicably, they had survived not one but two of the most formidable yokai that anyone could ever encounter, and had been rescued by none other than a magical sword. Their exploits would be celebrated for all time in the fishing community here, and perhaps it would never again be plagued by visitations from the nure-onna or from other ushi-oni. Then again, the yokai should never be underestimated. Even if these had gone, there were countless others ready to take their place.

Moreover, strange monsters are still reported occasionally from the wilder seas and shorelines around Japan today. Could they be unknown or unrecognised zoological species - or is this nation’s preternatural yokai clan very much alive and well even in our prosaic, ultra-scientific 21st Century?

Ushi-oni (Oda Yoshi, 1832)

Ushi-oni (Oda Yoshi, 1832)

Published on July 17, 2014 18:26

July 16, 2014

A MYSTERY MOTH FROM FAIRYLAND?

st1\:*{behavior:url(#ieooui) }

A snowberry clearwing – the identity of this ShukerNature blog article's North American mystery moth?

A snowberry clearwing – the identity of this ShukerNature blog article's North American mystery moth?Occasionally, a mystery animal report so strange and singular comes to light that it defies any serious attempt at explanation.

One such example was forwarded on 26 May 1998 to what later became the cz@yahoogroups.com cryptozoology discussion group (now defunct) by its founder, American cryptozoologist Chad Arment. He had received it from a Tennessee correspondent, and it reads as follows:

"The insect that I saw was humming a song. I was on top of a hill and thought that I was hearing a radio or something like that but I noticed this little bug [and] the closer it got the more like a song it became. This little bug was flying upright like a ...fairy! I was really excited because I thought what I saw was what people in earlier times might have mistaken for real sprites. This bug went from tree to tree and from flower to flower stopping at each one. I didn't see it eat anything but like I said I was excited. It was about 2" long "tall" and white[,] had blue eyes large almond shaped and long antennae that hung like hair. It was really quite intriguing but as I moved to get a better look it saw me and went horizontal and was off like a shot. Also the humming stopped when it saw me and it just buzzed away."

Reading through this extraordinary report, images of hawk moths readily come to mind, in particular something along the lines of the hummingbird hawk moth Macroglossum stellatarum – named after its famously deceptive outward and behavioural similarity to a bona fide hummingbird. Having said that, this insect is an exclusively Old World species, but could there be an undiscovered New World representative?

1840s colour illustration of the hummingbird hawk moth, from John Curtis's British Entomology

1840s colour illustration of the hummingbird hawk moth, from John Curtis's British EntomologyMore plausible is that it was a specimen of what is commonly termed a hummingbird hawk moth in the Americas but known in the Old World as a bee hawk moth. Four species belonging to the genus Hemaris are known from North and South America.

The common clearwing (© Mdf/Wikipedia)

The common clearwing (© Mdf/Wikipedia)Day-flying, they do resemble hummingbirds, but with transparent wings (earning them the alternative name of clearwing moths) that make them look somewhat ethereal too. Moreover, I have seen photos of these fascinating little insects in which their shiny compound eyes appear blue in colour, and at least two species, the snowberry clearwing Hemaris diffinis and common clearwing H. thysbe, are indeed native to Tennessee.

Sadly, however, with only a single report on file, there seems little chance of ever obtaining a conclusive identification for Tennessee's entomological fairy (for my ShukerNature investigation of another enigmatic lepidopteran - the Venezuelan poodle moth - click here ).

Vintage illustration of a moth-winged fairy (public domain)

Vintage illustration of a moth-winged fairy (public domain)

Published on July 16, 2014 18:10

July 13, 2014

CREEPY CREATIONS AND CRYPTOZOOLOGY – MONSTROUSLY-AWESOME ARTWORK FROM SHIVER AND SHAKE

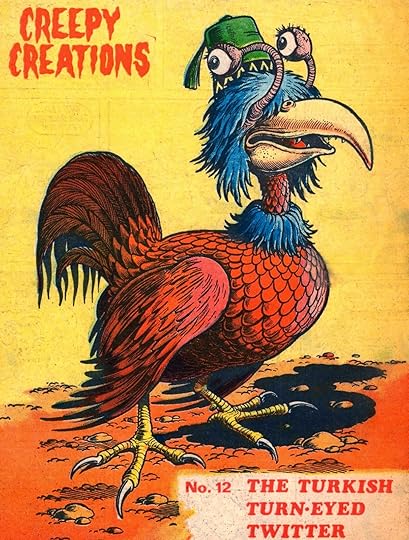

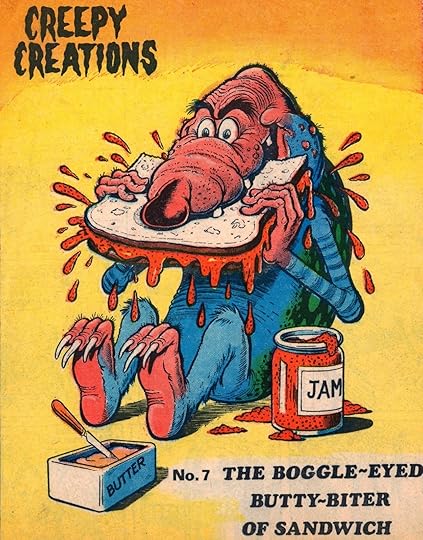

The Turkish Turn-Eyed Twitter – one of my favourite Creepy Creations (© Kevin Reid/IPC)

The Turkish Turn-Eyed Twitter – one of my favourite Creepy Creations (© Kevin Reid/IPC)Unless, like me, you were a child or early teenager in Britain during the 1970s, the title of this present ShukerNature blog post will very probably leave you totally bemused – so let me explain what it's all about. One of the many British weekly comics that I used to read during that period was published by IPC and entitled Shiver and Shake – actually two comics in one, with Shake enclosed in the centre of Shiver. Starting with issue #1 (published 10 March 1973), every week the back cover of Shivershowcased a wonderful series of monster artwork known as Creepy Creations, which were mostly drawn by cartoonist Ken Reid.

The One-Eyed Wonk of Wigan – the very first Creepy Creation (© Kevin Reid/IPC)

The One-Eyed Wonk of Wigan – the very first Creepy Creation (© Kevin Reid/IPC)The first few were created specifically by Ken, but then the series became the focus of a long-running competition, whereby readers would be invited to send in sketches of their own monster creations, and the best entry each week as selected by the comic's editor would be redrawn professionally by Ken and then appear on the back cover; the winner would also receive a modest monetary prize - £1 - plus (if memory serves me correctly) Ken's original artwork of their monster.

The Boggle-Eyed Butty-Biter of Sandwich – not just a Creepy Creation but also a jam-devouring relation, perhaps, of the honey-loving Winnie the Pooh? (© Kevin Reid/IPC)

The Boggle-Eyed Butty-Biter of Sandwich – not just a Creepy Creation but also a jam-devouring relation, perhaps, of the honey-loving Winnie the Pooh? (© Kevin Reid/IPC)In total, 79 winning Creepy Creations entries appeared in the comic itself (as well as a number of runners-up, plus additional examples in the various Shiver and Shake Holiday Specials and Shiver and Shake Annuals), and they were all given titles that were hilariously alliterative and outrageously contrived, thus adding immensely to the fun.

The Trumpington Trumpeter – is this where Rothschild's mystery tusk came from? :-) (© Kevin Reid/IPC)

The Trumpington Trumpeter – is this where Rothschild's mystery tusk came from? :-) (© Kevin Reid/IPC)I used to love this series – especially the more cryptozoological examples, naturally - and I still have a few that I cut out way back then and have kept ever since, some of which I've scanned and included in this post. All of which goes to show that it was not only the serious works of Heuevelmans et al. that inspired, encouraged, and nurtured my fascination with monsters and mystery beasts!

Dripula, the Monster from the Swamp – not a cryptozoologically-themed Creepy Creation but still a favourite of mine because I always felt that it would have made a very successful movie monster (© Kevin Reid/IPC)

Dripula, the Monster from the Swamp – not a cryptozoologically-themed Creepy Creation but still a favourite of mine because I always felt that it would have made a very successful movie monster (© Kevin Reid/IPC)If you'd like to learn a lot more about Creepy Creations, click here for a very informative page concerning them, including illustrations of several of the best examples plus a complete itemised listing; and click here for an extremely comprehensive series of Creepy Creations illustrations, showcasing many if not all of them.

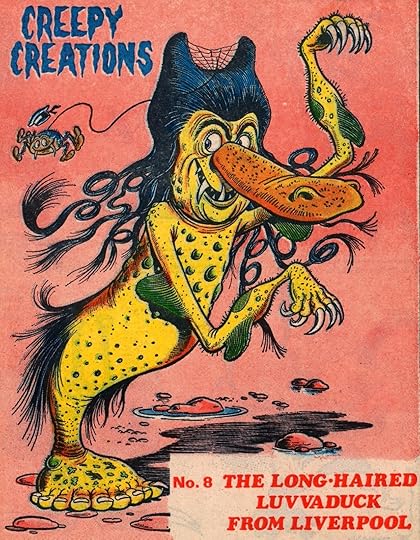

The Long-Haired Luvvaduck From Liverpool – Little Jimmy Osmond was in the pop charts at the time! (© Kevin Reid/IPC)

The Long-Haired Luvvaduck From Liverpool – Little Jimmy Osmond was in the pop charts at the time! (© Kevin Reid/IPC)Now, if only some enterprising publisher could issue a compilation edition…

The Hooter-Hiker of Harrogate – weirdly wonderful, or wonderfully weird? (© Kevin Reid/IPC)

The Hooter-Hiker of Harrogate – weirdly wonderful, or wonderfully weird? (© Kevin Reid/IPC)But to think that Creepy Creations began over 40 years ago – where does the time go?! And how sad that the once-thriving, burgeoning array of British comics - in their heyday when I was young - have long since vanished. Today, just a single example, The Beano, survives, with even its longstanding sidekick The Dandy lately relegated to an online-only presence. Ah well, at least I still have my good memories of them (together with a few yellowing copies and some hardback annuals). Good memories indeed, of happy bygone days.

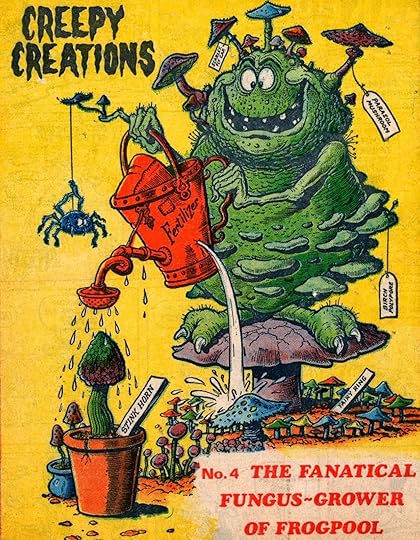

The Fanatical Fungus-Grower of Frogpool – is there really a place called Frogpool?? (© Kevin Reid/IPC)

The Fanatical Fungus-Grower of Frogpool – is there really a place called Frogpool?? (© Kevin Reid/IPC)

Published on July 13, 2014 18:37

July 12, 2014

GRIFFINS, GRIFFINOSAURS, CYNOGRIFFINS, AND HIPPOGRIFFS – REVISITING SOME CLASSIC MIX 'N' MATCH MONSTERS FROM FABLE, FICTION, AND FACT

A beautiful majolica jardinière from the late 19th Century in the form of a senmurv or cynogriffin (© Dr Karl Shuker)

A beautiful majolica jardinière from the late 19th Century in the form of a senmurv or cynogriffin (© Dr Karl Shuker)My maternal grandmother's family surname was Griffin, in honour of which I have a griffin tattoo, so this famous beast of ancient myth and legend has always been special to me. A fabulous mix 'n' match monster combining the body of a lion with the wings and head of an eagle, and alternatively spelled as 'gryphon', it apparently originated in the Levantregion, with accounts of griffins from this area dating back more than 4000 years, but later spreading their mighty pinions westward into Europe.

A ceramic griffin figurine (© Dr Karl Shuker)

A ceramic griffin figurine (© Dr Karl Shuker)These amalgamated animals were well-known for their fondness for gold - Greek historian Herodotus, writing in the 5th Century BC, stated that griffins inhabited the lofty mountain peaks of India, where they dug up gold with which to construct their mighty nests, which in turn were greatly coveted by opportunist gold-hunters.

Griffin engraving from 1663

Griffin engraving from 1663Also highly sought-after were their long curved talons, allegedly capable of detecting poison, and many were brought back to Europeduring the Middle Ages by crusaders. Sadly, however, they invariably proved to be antelope horns, sold to the ingenuous crusaders by African entrepreneurs! As noted by Edward Peacock in the September 1884 issue of The Antiquary, for instance, a supposed griffin claw now preserved in the British Museum is believed to have been one of two contained in 1383 within the shrine of Saint Cuthbert at Durham Cathedral. However, it bears a very close resemblance indeed to the horn of an ibex!

Nubian ibex revealing its magnificent curled horns, once passed off as griffin claws by unscrupulous Middle Eastern vendors to gullible Crusaders (© Nino Barbieri/Wikipedia)

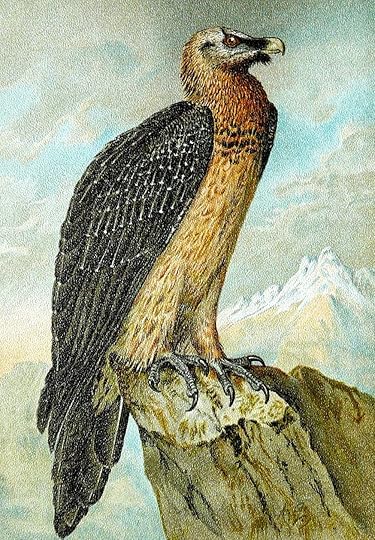

Nubian ibex revealing its magnificent curled horns, once passed off as griffin claws by unscrupulous Middle Eastern vendors to gullible Crusaders (© Nino Barbieri/Wikipedia)Traditionally, zoologists have sought to identify the griffin with a powerful species of vulturine bird of prey called the lammergeier Gypaetus barbatus, but in 1991 avery novel alternative candidate was proposed by Dr Adrienne Mayor, a classical scholar currently at California's Stanford University.

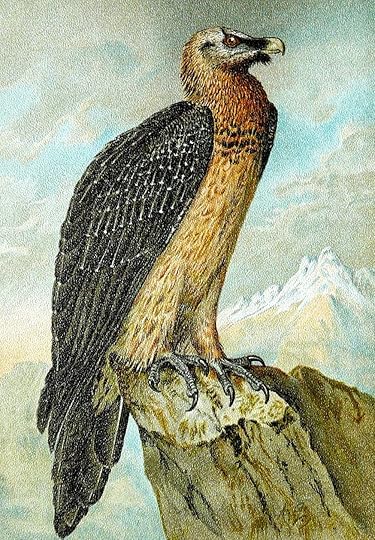

Lammergeier – a German chromolithograph from 1894

Lammergeier – a German chromolithograph from 1894Dr Mayor noted that the Altai Mountains of central Asia, famous for their rich gold deposits and the locality of many ancient griffin legends, also contain the fossilised skeletons and eggs of a lion-sized species of quadrupedal ceratopsian dinosaur called Protoceratops andrewsi, whose most distinctive feature was its strikingly eagle-like beaked head.

Life-sized model of Protoceratops andrewsi (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Life-sized model of Protoceratops andrewsi (© Dr Karl Shuker)Dating from the late Cretaceous Period (approximately 70 million years ago), if its remains had been encountered by early gold prospectors many centuries before the correct nature of dinosaurs as prehistoric reptiles was recognised, how would these veritable griffinosaurs have been explained by such people? Quite possibly as the skeletons of four-footed eagle-headed monsters - or, as we call them today, griffins.

Griffin statue spotted in the yard of a statue/figurine seller in Rome, 2001 (© Dr Karl Shuker)

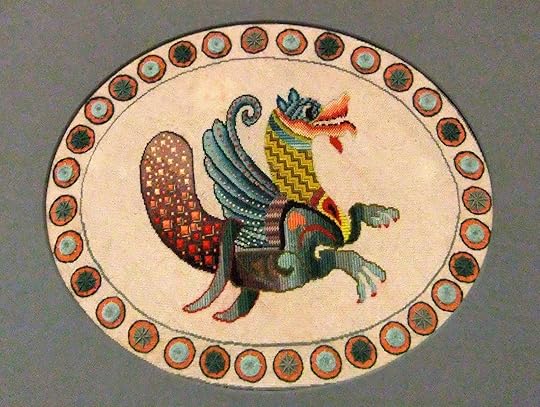

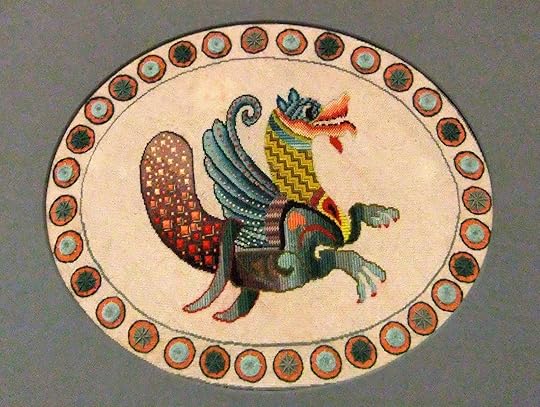

Griffin statue spotted in the yard of a statue/figurine seller in Rome, 2001 (© Dr Karl Shuker)Closely allied (if not directly ancestral) to the griffin, and sometimes termed the cynogriffin, is the senmurv ('dog-bird') of early Persian mythology, which combines the body of a lion, and the wings and talons of an eagle, with the head of a dog. Its home was a magical tree, whose seeds, scattered throughout the world whenever the senmurv alighted in its mighty branches, cured diseases and evils of every kind.

Embroidered senmurv, based upon the royal symbol of the Sassanian Empire of 224-651 AD (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Embroidered senmurv, based upon the royal symbol of the Sassanian Empire of 224-651 AD (© Dr Karl Shuker)Later Persian legends transformed the senmurv into a huge, resplendent bird known as the simurgh, which nested on the highest peak of northern Persia's Alburz Mountains, and was permanently hidden from mortal view behind a shimmering veil of darkness and light. Nevertheless, this supposedly unseen bird was frequently, and lavishly, portrayed in ancient bestiaries and manuscripts - a paradoxical situation that incited one short-tempered scholar long ago to pen the following terse but apt comment in the margin of an exquisite plate depicting the simurgh in a 13th Century bestiary: "Thou fool, if nobody has seen the simurgh, then how dost thou portray it?".

Simurgh depicted upon the portal of Nadir Divan-Beghi Madrasah, in Bukhara, Uzbekistan (© Alaexis/Wikipedia)

Simurgh depicted upon the portal of Nadir Divan-Beghi Madrasah, in Bukhara, Uzbekistan (© Alaexis/Wikipedia)Folklorists consider it most likely that the simurgh was based upon one or more of the large vultures and eagles native to Iran and elsewhere in the Middle East, and its 'evolution' was probably also influenced by Arabian myths of the enormous roc or rukh - a gargantuan bird of prey that could carry elephants aloft in its huge talons and inhabited an unspecified island in the Indian Ocean. As documented in further detail elsewhere on ShukerNature (click here ), fronds from the exceptionally large raffia palm tree Sagus ruffia were once believed to be the feathers of the roc.

Supposed roc feather, in reality a frond from the raffia palm tree (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Supposed roc feather, in reality a frond from the raffia palm tree (© Dr Karl Shuker)Yet however improbable dinosaur-inspired griffins and dog-headed griffins (not to mention elephant-abducting giant birds!) might seem, they all pale into insignificance when compared with a certain category of griffin that was so unlikely it was specifically created to personify the concept of impossibility - namely, the hippogriff. According to mythology, the rapacious griffin would readily attack and devour a horse, and in any case these two animal types were entirely dissimilar in form from one another. So how could anyone believe that they might ever mate and yield viable offspring (always assuming, of course, that anyone could actually believe that griffins themselves were real)? Such an unnatural liaison would clearly be impossible, but even if somehow it might indeed take place, no offspring could ever result from it. Thus originated the notion of the hippogriff, as put initially coined (though not actually named, merely alluded to) by Roman poet Virgil (70-19 BC) in his Eclogues, as the embodiment of all that could never be - except that like so many other fictitious monsters, the hippogriff ultimately took on a veritable life of its own.

'Roger Délivrant Angélique' ('Roger rescuing Angelica'), painted by Louis-Édouard Rioult in 1824

'Roger Délivrant Angélique' ('Roger rescuing Angelica'), painted by Louis-Édouard Rioult in 1824 Uniting the head, plumed wings, and front limbs of an eagle with the body, hind limbs, and tail of a horse, the hippogriff presented such a spectacular image that it became a popular subject for Classical artists to portray, it appeared in heraldry on several notable coats of arms, and in the poem Orlando Furioso ('Mad Orlando') penned by Ludovico Ariosto in 1516 this monumentally mixed 'n' matched monster was formally designated the name 'hippogriff' (also spelled 'hippogryph'). In this latter literary work, the wandering knight Roger rescues the fair Angelica from a voracious sea dragon while riding the airborne hippogriff - a beast of such astounding flying ability that it can soar entirely around the earth without pausing, and even take wing to the moon and back. During the 19th Century, Gustave Doré (1832-1883) produced some striking images of the hippogriff in his celebrated series of engravings illustrating Ariosto's poem.

Roger rescuing Angelica, portrayed by Gustave Doré

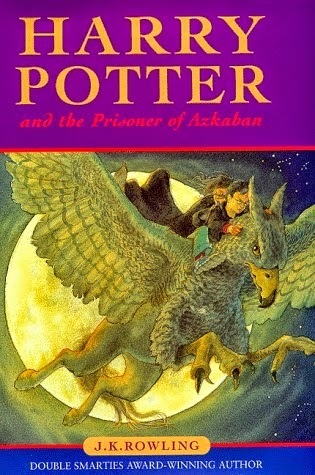

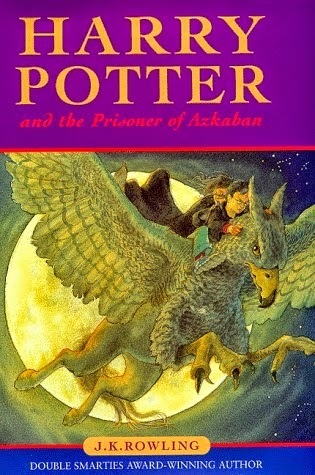

Roger rescuing Angelica, portrayed by Gustave DoréWithout any doubt, however, the most famous modern-day representation of this fabulous animal is Buckbeak, the prominently-featured hippogriff in the bestselling Harry Potter series of teenage wizard and wizardry novels by J.K. Rowling, which has introduced to millions of readers worldwide what had hitherto been for centuries a somewhat obscure fantasy beast. Not bad at all for a creature originally invented expressly to signify anything that could never exist!

Buckbeak the hippogriff as depicted upon the front cover of The Prisoner of Azkaban, the third Harry Potter novel (© J.K. Rowling/Bloomsbury)

Buckbeak the hippogriff as depicted upon the front cover of The Prisoner of Azkaban, the third Harry Potter novel (© J.K. Rowling/Bloomsbury)

Published on July 12, 2014 04:59

GRIFFINOSAURS, CYNOGRIFFINS, AND HIPPOGRIFFS – REVISITING SOME CLASSIC MIX 'N' MATCH MONSTERS FROM FABLE, FICTION, AND FACT

A beautiful majolica jardinière from the late 19th Century in the form of a senmurv or cynogriffin (© Dr Karl Shuker)

A beautiful majolica jardinière from the late 19th Century in the form of a senmurv or cynogriffin (© Dr Karl Shuker)My maternal grandmother's family surname was Griffin, in honour of which I have a griffin tattoo, so this famous beast of ancient myth and legend has always been special to me. A fabulous mix 'n' match monster combining the body of a lion with the wings and head of an eagle, and alternatively spelled as 'gryphon', it apparently originated in the Levantregion, with accounts of griffins from this area dating back more than 4000 years, but later spreading their mighty pinions westward into Europe.

A ceramic griffin figurine (© Dr Karl Shuker)

A ceramic griffin figurine (© Dr Karl Shuker)These amalgamated animals were well-known for their fondness for gold - Greek historian Herodotus, writing in the 5th Century BC, stated that griffins inhabited the lofty mountain peaks of India, where they dug up gold with which to construct their mighty nests, which in turn were greatly coveted by opportunist gold-hunters.

Griffin engraving from 1663

Griffin engraving from 1663Also highly sought-after were their long curved talons, allegedly capable of detecting poison, and many were brought back to Europeduring the Middle Ages by crusaders. Sadly, however, they invariably proved to be antelope horns, sold to the ingenuous crusaders by African entrepreneurs! As noted by Edward Peacock in the September 1884 issue of The Antiquary, for instance, a supposed griffin claw now preserved in the British Museum is believed to have been one of two contained in 1383 within the shrine of Saint Cuthbert at Durham Cathedral. However, it bears a very close resemblance indeed to the horn of an ibex!

Nubian ibex revealing its magnificent curled horns, once passed off as griffin claws by unscrupulous Middle Eastern vendors to gullible Crusaders (© Nino Barbieri/Wikipedia)

Nubian ibex revealing its magnificent curled horns, once passed off as griffin claws by unscrupulous Middle Eastern vendors to gullible Crusaders (© Nino Barbieri/Wikipedia)Traditionally, zoologists have sought to identify the griffin with a powerful species of vulturine bird of prey called the lammergeier Gypaetus barbatus, but in 1991 avery novel alternative candidate was proposed by Dr Adrienne Mayor, a classical scholar currently at California's Stanford University.

Lammergeier – a German chromolithograph from 1894

Lammergeier – a German chromolithograph from 1894Dr Mayor noted that the Altai Mountains of central Asia, famous for their rich gold deposits and the locality of many ancient griffin legends, also contain the fossilised skeletons and eggs of a lion-sized species of quadrupedal ceratopsian dinosaur called Protoceratops andrewsi, whose most distinctive feature was its strikingly eagle-like beaked head.

Life-sized model of Protoceratops andrewsi (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Life-sized model of Protoceratops andrewsi (© Dr Karl Shuker)Dating from the late Cretaceous Period (approximately 70 million years ago), if its remains had been encountered by early gold prospectors many centuries before the correct nature of dinosaurs as prehistoric reptiles was recognised, how would these veritable griffinosaurs have been explained by such people? Quite possibly as the skeletons of four-footed eagle-headed monsters - or, as we call them today, griffins.

Griffin statue spotted in the yard of a statue/figurine seller in Rome, 2001 (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Griffin statue spotted in the yard of a statue/figurine seller in Rome, 2001 (© Dr Karl Shuker)Closely allied (if not directly ancestral) to the griffin, and sometimes termed the cynogriffin, is the senmurv ('dog-bird') of early Persian mythology, which combines the body of a lion, and the wings and talons of an eagle, with the head of a dog. Its home was a magical tree, whose seeds, scattered throughout the world whenever the senmurv alighted in its mighty branches, cured diseases and evils of every kind.

Embroidered senmurv, based upon the royal symbol of the Sassanian Empire of 224-651 AD (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Embroidered senmurv, based upon the royal symbol of the Sassanian Empire of 224-651 AD (© Dr Karl Shuker)Later Persian legends transformed the senmurv into a huge, resplendent bird known as the simurgh, which nested on the highest peak of northern Persia's Alburz Mountains, and was permanently hidden from mortal view behind a shimmering veil of darkness and light. Nevertheless, this supposedly unseen bird was frequently, and lavishly, portrayed in ancient bestiaries and manuscripts - a paradoxical situation that incited one short-tempered scholar long ago to pen the following terse but apt comment in the margin of an exquisite plate depicting the simurgh in a 13th Century bestiary: "Thou fool, if nobody has seen the simurgh, then how dost thou portray it?".

Simurgh depicted upon the portal of Nadir Divan-Beghi Madrasah, in Bukhara, Uzbekistan (© Alaexis/Wikipedia)

Simurgh depicted upon the portal of Nadir Divan-Beghi Madrasah, in Bukhara, Uzbekistan (© Alaexis/Wikipedia)Folklorists consider it most likely that the simurgh was based upon one or more of the large vultures and eagles native to Iran and elsewhere in the Middle East, and its 'evolution' was probably also influenced by Arabian myths of the enormous roc or rukh - a gargantuan bird of prey that could carry elephants aloft in its huge talons and inhabited an unspecified island in the Indian Ocean. As documented in further detail elsewhere on ShukerNature (click here ), fronds from the exceptionally large raffia palm tree Sagus ruffia were once believed to be the feathers of the roc.

Supposed roc feather, in reality a frond from the raffia palm tree (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Supposed roc feather, in reality a frond from the raffia palm tree (© Dr Karl Shuker)Yet however improbable dinosaur-inspired griffins and dog-headed griffins (not to mention elephant-abducting giant birds!) might seem, they all pale into insignificance when compared with a certain category of griffin that was so unlikely it was specifically created to personify the concept of impossibility - namely, the hippogriff. According to mythology, the rapacious griffin would readily attack and devour a horse, and in any case these two animal types were entirely dissimilar in form from one another. So how could anyone believe that they might ever mate and yield viable offspring (always assuming, of course, that anyone could actually believe that griffins themselves were real)? Such an unnatural liaison would clearly be impossible, but even if somehow it might indeed take place, no offspring could ever result from it. Thus originated the notion of the hippogriff, as put initially coined (though not actually named, merely alluded to) by Roman poet Virgil (70-19 BC) in his Eclogues, as the embodiment of all that could never be - except that like so many other fictitious monsters, the hippogriff ultimately took on a veritable life of its own.

'Roger Délivrant Angélique' ('Roger rescuing Angelica'), painted by Louis-Édouard Rioult in 1824

'Roger Délivrant Angélique' ('Roger rescuing Angelica'), painted by Louis-Édouard Rioult in 1824 Uniting the head, plumed wings, and front limbs of an eagle with the body, hind limbs, and tail of a horse, the hippogriff presented such a spectacular image that it became a popular subject for Classical artists to portray, it appeared in heraldry on several notable coats of arms, and in the poem Orlando Furioso ('Mad Orlando') penned by Ludovico Ariosto in 1516 this monumentally mixed 'n' matched monster was formally designated the name 'hippogriff' (also spelled 'hippogryph'). In this latter literary work, the wandering knight Roger rescues the fair Angelica from a voracious sea dragon while riding the airborne hippogriff - a beast of such astounding flying ability that it can soar entirely around the earth without pausing, and even take wing to the moon and back. During the 19th Century, Gustave Doré (1832-1883) produced some striking images of the hippogriff in his celebrated series of engravings illustrating Ariosto's poem.

Roger rescuing Angelica, portrayed by Gustave Doré

Roger rescuing Angelica, portrayed by Gustave DoréWithout any doubt, however, the most famous modern-day representation of this fabulous animal is Buckbeak, the prominently-featured hippogriff in the bestselling Harry Potter series of teenage wizard and wizardry novels by J.K. Rowling, which has introduced to millions of readers worldwide what had hitherto been for centuries a somewhat obscure fantasy beast. Not bad at all for a creature originally invented expressly to signify anything that could never exist!

Buckbeak the hippogriff as depicted upon the front cover of The Prisoner of Azkaban, the third Harry Potter novel (© J.K. Rowling/Bloomsbury)

Buckbeak the hippogriff as depicted upon the front cover of The Prisoner of Azkaban, the third Harry Potter novel (© J.K. Rowling/Bloomsbury)

Published on July 12, 2014 04:59

July 9, 2014

GIANT BLACK UNICORNS, A CHINESE QUASI-RHINO FIGURINE, AND THE ENIGMA OF ELASMOTHERIUM

A magnificent restoration of the giant unicorn – a brow-horned Pleistocene rhinoceros known formally as Elasmotherium(© Zdenek Burian)

A magnificent restoration of the giant unicorn – a brow-horned Pleistocene rhinoceros known formally as Elasmotherium(© Zdenek Burian)As I documented in an extremely comprehensive chapter within my book Dr Shuker's Casebook: In Pursuit of Marvels and Mysteries (2008) and subsequently added to in a ShukerNature blog article (click here ), a very considerable number of unicorn varieties have been differentiated in legends and folklore from around the world – everything from shape-shifting were-unicorns, carnivorous rabbit unicorns, polar bear unicorns with glowing horns, web-footed unicorns, swivel-horned unicorns, and man-eating unicorns with musical horns, to unicorn birds, unicorn snakes, unicorn snails, unicorn pigs, artificially-induced unicorns, and even two-horned unicorns (surely a contradiction in terms!).

One of the least-known members of this diverse array, however, is also among of the most fascinating – the giant black unicorn of Siberia. For this spectacular creature is not only of interest to students of animal mythology but may have significant cryptozoological relevance too.

The traditional lore of Siberia’s Evenk people tells of a huge black bull-like creature bearing a single round, thick, tapering horn of immense size upon the middle of its head. This notoriously belligerent beast would charge at any Evenk rider that it spied, tossing the unfortunate man into the air if it could reach him, and spearing him when he fell back down to earth until he died. Moreover, its horn was so large and heavy that if one of these mega-unicorns were killed, the horn alone needed an entire sledge to transport it. Could this awesome but ostensibly fictitious animal have been inspired at least in part by a living species?

The Lungfish, the Dodo, and the Unicorn

The Lungfish, the Dodo, and the Unicorn

In his book The Lungfish, the Dodo, and the Unicorn (1948), veteran cryptozoological writer Willy Ley presented a fascinating line of speculation as to the possible origin of the Evenk people's traditional lore concerning giant black unicorns of ferocious demeanour:

"The paleontologists of around the year 1900 began to believe that they had successfully discovered the original unicorn. In Russia and in Siberia bones and skulls of an extinct distant relative of the rhinoceros were discovered. This animal, Elasmotherium sibiricum, seemed to resemble the ancient reports [of unicorns] even more than does the living rhinoceros. It was noticeably larger than the largest Indian rhinoceros, its horn was much longer and was actually situated in the middle of the forehead of the animal. But after the first excitement had subsided, most scientists abandoned the idea that Elasmotherium had anything to do with the unicorn legend. However, as Melchior Neumayr wrote in his History of the Earth: it is possible that in Siberia man and Elasmotheriumactually lived together and that Elasmotherium was exterminated by man; at least one may explain in this way the ancient songs of the Tunguses [aka the Evenks], which tell that formerly there lived in their country a kind of terrible black ox of gigantic size and with only one horn in the middle of the forehead, so large that an entire sled was needed for the transportation of this horn alone."

Was Elasmotherium (above) the Evenks' giant black unicorn? (© Philip72/Wikipedia)

Was Elasmotherium (above) the Evenks' giant black unicorn? (© Philip72/Wikipedia)Up to 15 ft long and standing over 6.5 ft at the shoulder, E. sibiricum was comparable to a woolly mammoth Mammuthus primigenius in size, and (at least for a rhinoceros) had proportionately long legs. The last member of its genus, it is believed to have survived until at least as recently as 50,000 years ago, during the late Pleistocene epoch, and possibly even later than that, thereby making the hypothesis of survival for a time by this species alongside modern man in Siberia as outlined above by Ley neither impossible nor even overly implausible. An earlier species, E. caucasicum, had flourished in the Black Sea region of Europe during the early Pleistocene and was even bigger, up to 16 ft long and weighing an estimated 4-5 tons.

Reconstruction of a pair of Siberian giant unicorns Elasmotherium sibiricum (© Apokryltaros/Wikipedia)

Reconstruction of a pair of Siberian giant unicorns Elasmotherium sibiricum (© Apokryltaros/Wikipedia)Certainly, a huge gracile rhinoceros bearing a gargantuan horn not upon its snout's nasal bones like all known living rhino species today but upon its brow's frontal bones instead might well make a very convincing giant unicorn. And indeed, Elasmotheriumis commonly referred to informally by this exact name - the giant unicorn.

Nor is the huge black unicorn of Evenk lore the only evidence that has been put forward in support of the postulated if currently-unproven late survival of Elasmotheriumand its contemporaneous, pre-extermination existence alongside humanity in Asia. In 1958, two additional Elasmotherium species were formally named – E. inexpectatumand E. peii, both of which had lived in northern China during the early Pleistocene, becoming extinct around 1.6 million years ago. However, they were subsequently reclassified as Chinese representatives of E. caucasicum rather than separate species in their own respective right (meanwhile, fossil remains of a still-valid third species, E. chaprovicum, have been obtained from Europe and Asia, and date from 2.6 million to 2.2 million years ago).

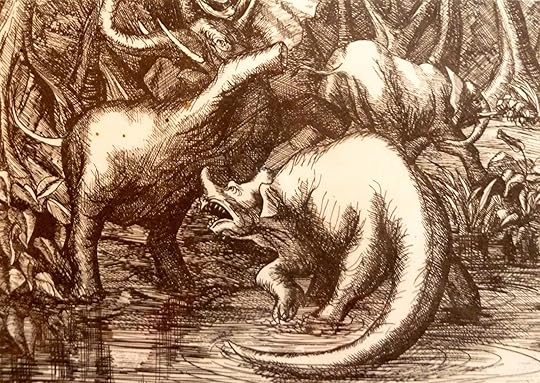

An enraged Elasmotherium versus a couple of pesky prehistoric felids (© Hodari Nundu/Deviantart.com)

An enraged Elasmotherium versus a couple of pesky prehistoric felids (© Hodari Nundu/Deviantart.com)Nevertheless, the onetime occurrence of any species of Elasmotherium in China is particularly intriguing, due to the existence of a certain very unusual and greatly perplexing example of Chinese iconography.

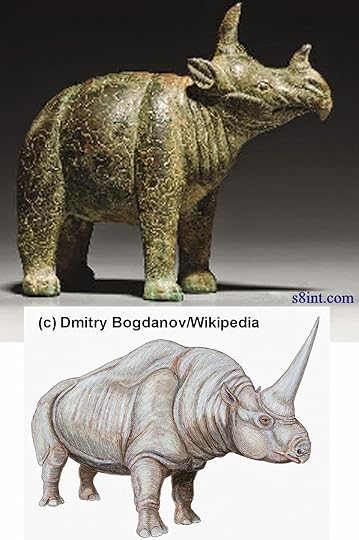

While browsing online on 8 August 2012, I came upon a photograph of a small but very distinctive and highly unusual animal figurine, made of bronze. On first sight, it somewhat resembled a rhinoceros, with a short pointed horn upon its snout – but a closer look revealed that this horn curved forwards, whereas those of rhinos normally curve backwards. Moreover, its body did not bear any 'armour pleats' like those exhibited to varying degrees by all five rhino species alive today. Even more striking, however, was something that it did bear – a second, larger horn…but not upon its nasal bones. Instead, projecting slightly forwards, it arose directly from the centre of the creature's brow – just like the horn of a unicorn!

The photograph depicting this intriguing figurine (reproduced below) appeared on the s8int.com website, which offers a biblical perspective on science (including cryptozoology), and is written by Chris Parker. Accompanying the photograph were details of its origin and recent history, followed by Parker's thoughts as to what type of creature it may represent.

The mystifying Chinese quasi-rhino figurine (copyright owner unknown to me/image source online = http://s8int.com/WordPress/)

The mystifying Chinese quasi-rhino figurine (copyright owner unknown to me/image source online = http://s8int.com/WordPress/)Those details revealed that the figurine was in excellent condition and dated from China's Tang Dynasty (618-907 AD), an extremely formidable combination as far as its value as a collectible objet d'art was concerned, because in 2007 it was sold at auction by Christies in London for the staggering sum of US$ 216,000 !!

The Lot description for it that was provided by Christies read as follows:

"A RARE AND SMALL BRONZE FIGURE OF A RHINOCEROS

TANG DYNASTY (618-907 AD)

"Shown standing four-square with tail flicked to the left, the head well cast with two horns of different length, ears pricked back, small eyes and downward curved, overlapping muzzle sensitively cast along the upper edges of the mouth with folds in the skin, which can also be seen in the skin of the neck and chest, the thick hide indicated by overlapping wave pattern diminishing in size on the head and legs, with a rectangular aperture in the belly, the dark brownish surface with some patches of dark red patina and green encrustation.

"Lot Notes

"The depiction of the rhinoceros in bronze is very rare, especially during the Tang period. Earlier depictions do exist, however, as evidenced by the late Shang rhinoceros zun [i.e. an ancient Chinese wine vessel made of bronze or ceramic] in the Avery Brundage Collection, illustrated by d’Argencè, The Ancient Chinese Bronzes, San Francisco, 1966, pl. XIX and another large zun (22 7/8in. long), ornately decorated, but quite realistic in its depiction of a rhinoceros, of late Eastern Zhou/Western Han dynasty date, found in Xingping Xian, Shaanxi province, included in the exhibition, The Great Bronze Age of China, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1980, New York, Catalogue, no. 93"

So, in spite of the fundamental differences in morphology exhibited by this figurine, it was nonetheless deemed to be a rhinoceros by whoever had prepared its Lot description at Christies. One can only assume, therefore, that the writer in question was determined to identify it, however tenuously, with some known animal type, and/or was not a zoologist!

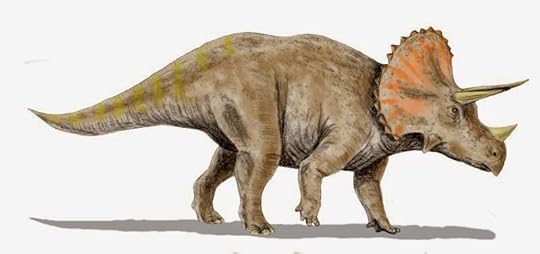

Triceratops

, the most famous genus of ceratopsian dinosaur (© Nobu Tamura/Wikipedia)

Triceratops

, the most famous genus of ceratopsian dinosaur (© Nobu Tamura/Wikipedia)Swiftly dismissing the rhinoceros from serious consideration as the figurine's basis, Parker offered up a very thought-provoking if dramatic alternative – a ceratopsian dinosaur. Known colloquially as the horned dinosaurs, this group included such prehistoric stalwarts as Triceratops, Styracosaurus, and Monoclonius(aka Centrosaurus). Officially, of course, like all dinosaurs, the last ceratopsians became extinct around 65 million years ago, at the end of the Cretaceous Period. But could a ceratopsian lineage have somehow survived beyond the Cretaceous and persisted right up and into the present day, undiscovered by science but represented iconographically by this perplexing work of ancient Chinese art?

Sadly for such an exciting prospect, the figurine lacks the bony neck frill characterizing quadrupedal ceratopsians, and its snout horn curves forward instead of backwards like that of ceratopsians. Also, its tail does not appear to be as long and hefty as that of the latter dinosaurs (this characteristic is deduced from the fact that in the photograph it is hidden on the creature's left side, whereas if it were of ceratopsian dimensions it would have been too big to have been concealed in this manner). Conversely, the figurine does possess what Parker interpreted as a beak, which if so would certainly help to ally it morphologically with the ceratopsians, because these reptiles famously sported large beaks. However, it simply looks to me like a large pointed upper lip, very similar in shape, in fact, to that of Africa's black rhinoceros Diceros bicornis.

Head of Chinese quasi-rhino figurine (top) and head of black rhinoceros (bottom), showing that the former apparently shares the latter's well-defined pointed upper lip

Head of Chinese quasi-rhino figurine (top) and head of black rhinoceros (bottom), showing that the former apparently shares the latter's well-defined pointed upper lipOf particular interest is that Parker then compared the figurine with a certain cryptid that has already been popularly linked to the idea of a putative modern-day ceratopsian – tropical Africa's emela-ntouka ('killer of elephants'). This is an aquatic snout-horned mystery beast that is said by native observers to disembowel with its long pointed horn any elephants recklessly trespassing within its swamp or lake domain (click here for more information regarding it). Unlike the Chinese figurine, however, the emela-ntouka does possess a very long, heavy ceratopsian-like tail, though it too is frill-less, and it also sports a pair of small but elephant-like ears – an incongruous feature indeed for any reptile to exhibit, thus indicating that it is mammalian rather than reptilian in identity.

Artistic impression of the emela-ntouka (© Jean Claude Thibault)

Artistic impression of the emela-ntouka (© Jean Claude Thibault)Parker concluded his account by briefly considering the mythological Chinese unicorn, noting that one Chinese researcher has proposed that depictions of this supposedly non-existent beast may in reality have been based upon sightings of a surviving species of Elasmotherium. Could the same identity thus explain the Chinese figurine too, he wondered?

Personally, I don't think so. To begin with, the figurine's snout-horn would be an anomaly for any Elasmotherium species currently known from the fossil record. In addition, even its brow horn, though correctly located, seems far too short and slender to be comparable to that of Elasmotherium. Conversely, its legs are indeed relatively long, like those of Elasmotherium, but its body is proportionately much too short and squat to be compatible with the huge 15-ft-plus length attributed by palaeontologists to the proportionately very long body of Elasmotherium. So I am certainly not persuaded personally by such an identity for it. As far as I am concerned, therefore, the mystery of this Chinese quasi-rhino figurine remains unresolved.

Chinese quasi-rhino figurine (top) compared with Elasmotherium (bottom)