GRIFFINOSAURS, CYNOGRIFFINS, AND HIPPOGRIFFS – REVISITING SOME CLASSIC MIX 'N' MATCH MONSTERS FROM FABLE, FICTION, AND FACT

A beautiful majolica jardinière from the late 19th Century in the form of a senmurv or cynogriffin (© Dr Karl Shuker)

A beautiful majolica jardinière from the late 19th Century in the form of a senmurv or cynogriffin (© Dr Karl Shuker)My maternal grandmother's family surname was Griffin, in honour of which I have a griffin tattoo, so this famous beast of ancient myth and legend has always been special to me. A fabulous mix 'n' match monster combining the body of a lion with the wings and head of an eagle, and alternatively spelled as 'gryphon', it apparently originated in the Levantregion, with accounts of griffins from this area dating back more than 4000 years, but later spreading their mighty pinions westward into Europe.

A ceramic griffin figurine (© Dr Karl Shuker)

A ceramic griffin figurine (© Dr Karl Shuker)These amalgamated animals were well-known for their fondness for gold - Greek historian Herodotus, writing in the 5th Century BC, stated that griffins inhabited the lofty mountain peaks of India, where they dug up gold with which to construct their mighty nests, which in turn were greatly coveted by opportunist gold-hunters.

Griffin engraving from 1663

Griffin engraving from 1663Also highly sought-after were their long curved talons, allegedly capable of detecting poison, and many were brought back to Europeduring the Middle Ages by crusaders. Sadly, however, they invariably proved to be antelope horns, sold to the ingenuous crusaders by African entrepreneurs! As noted by Edward Peacock in the September 1884 issue of The Antiquary, for instance, a supposed griffin claw now preserved in the British Museum is believed to have been one of two contained in 1383 within the shrine of Saint Cuthbert at Durham Cathedral. However, it bears a very close resemblance indeed to the horn of an ibex!

Nubian ibex revealing its magnificent curled horns, once passed off as griffin claws by unscrupulous Middle Eastern vendors to gullible Crusaders (© Nino Barbieri/Wikipedia)

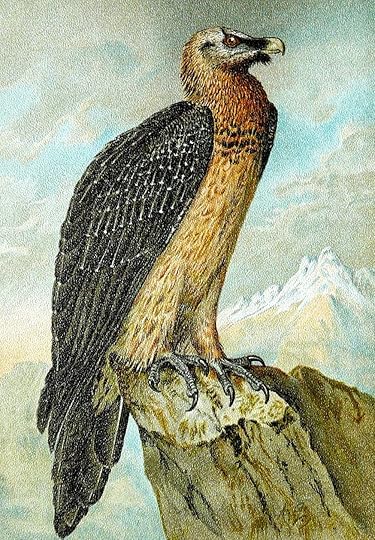

Nubian ibex revealing its magnificent curled horns, once passed off as griffin claws by unscrupulous Middle Eastern vendors to gullible Crusaders (© Nino Barbieri/Wikipedia)Traditionally, zoologists have sought to identify the griffin with a powerful species of vulturine bird of prey called the lammergeier Gypaetus barbatus, but in 1991 avery novel alternative candidate was proposed by Dr Adrienne Mayor, a classical scholar currently at California's Stanford University.

Lammergeier – a German chromolithograph from 1894

Lammergeier – a German chromolithograph from 1894Dr Mayor noted that the Altai Mountains of central Asia, famous for their rich gold deposits and the locality of many ancient griffin legends, also contain the fossilised skeletons and eggs of a lion-sized species of quadrupedal ceratopsian dinosaur called Protoceratops andrewsi, whose most distinctive feature was its strikingly eagle-like beaked head.

Life-sized model of Protoceratops andrewsi (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Life-sized model of Protoceratops andrewsi (© Dr Karl Shuker)Dating from the late Cretaceous Period (approximately 70 million years ago), if its remains had been encountered by early gold prospectors many centuries before the correct nature of dinosaurs as prehistoric reptiles was recognised, how would these veritable griffinosaurs have been explained by such people? Quite possibly as the skeletons of four-footed eagle-headed monsters - or, as we call them today, griffins.

Griffin statue spotted in the yard of a statue/figurine seller in Rome, 2001 (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Griffin statue spotted in the yard of a statue/figurine seller in Rome, 2001 (© Dr Karl Shuker)Closely allied (if not directly ancestral) to the griffin, and sometimes termed the cynogriffin, is the senmurv ('dog-bird') of early Persian mythology, which combines the body of a lion, and the wings and talons of an eagle, with the head of a dog. Its home was a magical tree, whose seeds, scattered throughout the world whenever the senmurv alighted in its mighty branches, cured diseases and evils of every kind.

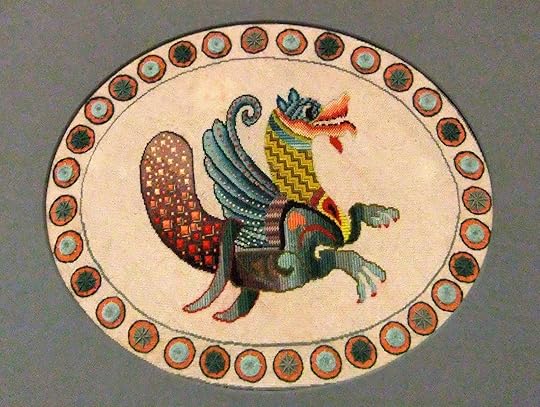

Embroidered senmurv, based upon the royal symbol of the Sassanian Empire of 224-651 AD (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Embroidered senmurv, based upon the royal symbol of the Sassanian Empire of 224-651 AD (© Dr Karl Shuker)Later Persian legends transformed the senmurv into a huge, resplendent bird known as the simurgh, which nested on the highest peak of northern Persia's Alburz Mountains, and was permanently hidden from mortal view behind a shimmering veil of darkness and light. Nevertheless, this supposedly unseen bird was frequently, and lavishly, portrayed in ancient bestiaries and manuscripts - a paradoxical situation that incited one short-tempered scholar long ago to pen the following terse but apt comment in the margin of an exquisite plate depicting the simurgh in a 13th Century bestiary: "Thou fool, if nobody has seen the simurgh, then how dost thou portray it?".

Simurgh depicted upon the portal of Nadir Divan-Beghi Madrasah, in Bukhara, Uzbekistan (© Alaexis/Wikipedia)

Simurgh depicted upon the portal of Nadir Divan-Beghi Madrasah, in Bukhara, Uzbekistan (© Alaexis/Wikipedia)Folklorists consider it most likely that the simurgh was based upon one or more of the large vultures and eagles native to Iran and elsewhere in the Middle East, and its 'evolution' was probably also influenced by Arabian myths of the enormous roc or rukh - a gargantuan bird of prey that could carry elephants aloft in its huge talons and inhabited an unspecified island in the Indian Ocean. As documented in further detail elsewhere on ShukerNature (click here ), fronds from the exceptionally large raffia palm tree Sagus ruffia were once believed to be the feathers of the roc.

Supposed roc feather, in reality a frond from the raffia palm tree (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Supposed roc feather, in reality a frond from the raffia palm tree (© Dr Karl Shuker)Yet however improbable dinosaur-inspired griffins and dog-headed griffins (not to mention elephant-abducting giant birds!) might seem, they all pale into insignificance when compared with a certain category of griffin that was so unlikely it was specifically created to personify the concept of impossibility - namely, the hippogriff. According to mythology, the rapacious griffin would readily attack and devour a horse, and in any case these two animal types were entirely dissimilar in form from one another. So how could anyone believe that they might ever mate and yield viable offspring (always assuming, of course, that anyone could actually believe that griffins themselves were real)? Such an unnatural liaison would clearly be impossible, but even if somehow it might indeed take place, no offspring could ever result from it. Thus originated the notion of the hippogriff, as put initially coined (though not actually named, merely alluded to) by Roman poet Virgil (70-19 BC) in his Eclogues, as the embodiment of all that could never be - except that like so many other fictitious monsters, the hippogriff ultimately took on a veritable life of its own.

'Roger Délivrant Angélique' ('Roger rescuing Angelica'), painted by Louis-Édouard Rioult in 1824

'Roger Délivrant Angélique' ('Roger rescuing Angelica'), painted by Louis-Édouard Rioult in 1824 Uniting the head, plumed wings, and front limbs of an eagle with the body, hind limbs, and tail of a horse, the hippogriff presented such a spectacular image that it became a popular subject for Classical artists to portray, it appeared in heraldry on several notable coats of arms, and in the poem Orlando Furioso ('Mad Orlando') penned by Ludovico Ariosto in 1516 this monumentally mixed 'n' matched monster was formally designated the name 'hippogriff' (also spelled 'hippogryph'). In this latter literary work, the wandering knight Roger rescues the fair Angelica from a voracious sea dragon while riding the airborne hippogriff - a beast of such astounding flying ability that it can soar entirely around the earth without pausing, and even take wing to the moon and back. During the 19th Century, Gustave Doré (1832-1883) produced some striking images of the hippogriff in his celebrated series of engravings illustrating Ariosto's poem.

Roger rescuing Angelica, portrayed by Gustave Doré

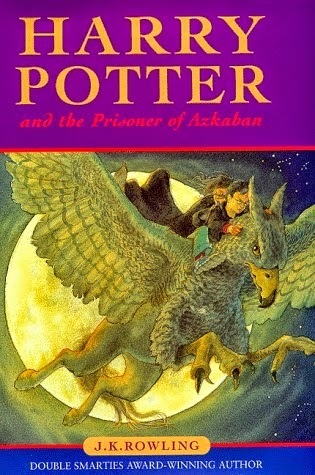

Roger rescuing Angelica, portrayed by Gustave DoréWithout any doubt, however, the most famous modern-day representation of this fabulous animal is Buckbeak, the prominently-featured hippogriff in the bestselling Harry Potter series of teenage wizard and wizardry novels by J.K. Rowling, which has introduced to millions of readers worldwide what had hitherto been for centuries a somewhat obscure fantasy beast. Not bad at all for a creature originally invented expressly to signify anything that could never exist!

Buckbeak the hippogriff as depicted upon the front cover of The Prisoner of Azkaban, the third Harry Potter novel (© J.K. Rowling/Bloomsbury)

Buckbeak the hippogriff as depicted upon the front cover of The Prisoner of Azkaban, the third Harry Potter novel (© J.K. Rowling/Bloomsbury)

Published on July 12, 2014 04:59

No comments have been added yet.

Karl Shuker's Blog

- Karl Shuker's profile

- 45 followers

Karl Shuker isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.