Martin Fowler's Blog, page 38

October 6, 2014

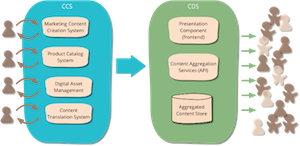

Building a two-stack CMS

Our Pune office recently did a project with a large manufacturer to build its global marketing website. The site involved complex content, lots of traffic (two million page views a day), localization to nearly a hundred locales, and high availability. In this infodeck my colleague Sunit Parekh and I dig into a key feature of the system - taking on the principle of Editing-Publishing Separation by building a two-stack architecture. This allowed the client to continue to use a wide range of software for their complex content editing needs, but at the same time providing a content delivery platform that supported a global site with high traffic and availability.

September 8, 2014

photostream 74

September 5, 2014

Setting up a ruby development VM with Vagrant, Chef, and rbenv

Some notes from my experiences in setting up a Vagrant VM to help collaborators use my web publishing toolchain. I used Chef to provision the VM and rbenv to install and control the right version of ruby.

August 31, 2014

Restoring a deleted note in Apple's notes app

I recently deleted a note on my Notes app on my apple laptop. As someone who is a paranoid keeper of backups, and usually commits all my work to a repository like git, I don’t worry much about accidental deletion. But Apple’s notes app doesn’t have any form of version control, and it’s all too easy to delete something by accident. I have a daily rsync backup and run time machine, but googling couldn’t uncover a simple way of getting the note back. So in case someone else needs to do this, here’s what I did.

August 30, 2014

photostream 73

August 29, 2014

Bliki: MicroservicePrerequisites

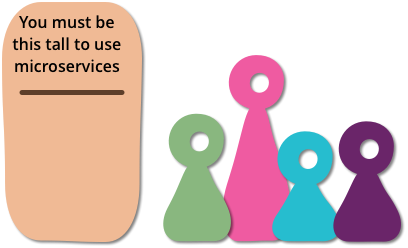

As I talk to people about using a microservices architectural

style I hear a lot of optimism. Developers enjoy working with

smaller units and have expectations of better modularity than with

monoliths. But as with any architectural decision there are

trade-offs. In particular with microservices there are serious

consequences for operations, who now have to handle an ecosystem of

small services rather than a single, well-defined monolith.

Consequently if you don't have certain baseline competencies, you

shouldn't consider using the microservice style.

Rapid provisioning: you should be able to fire up a new server in

a matter of hours. Naturally this fits in with

CloudComputing, but it's also something that can be done

without a full cloud service. To be able to do such rapid

provisioning, you'll need a lot of automation - it may not have to

be fully automated to start with, but to do serious microservices

later it will need to get that way.

Basic Monitoring: with many loosely-coupled services

collaborating in production, things are bound to go wrong in ways

that are difficult to detect in test environments. As a result it's

essential that a monitoring regime is in place to detect serious

problems quickly. The baseline here is detecting technical issues

(counting errors, service availability, etc) but it's also worth

monitoring business issues (such as detecting a drop in orders). If

a sudden problem appears then you need to ensure you can quickly

rollback, hence…

Rapid application deployment: with many services to mangage, you

need to be able to quickly deploy them, both to test environments

and to production. Usually this will involve a

DeploymentPipeline that can execute in no more than a

couple of hours. Some manual intervention is alright in the early

stages, but you'll be looking to fully automate it soon.

These capabilities imply an important organizational shift -

close collaboration between developers and operations: the DevOps

culture. This collaboration is needed to ensure that provisioning

and deployment can be done rapidly, it's also important to ensure

you can react quickly when your monitoring indicates a problem. In

particular any incident management needs to involve the development

team and operations, both in fixing the immediate problem and the

root-cause analysis to ensure the underlying problems are fixed.

With this kind of setup in place, you're ready for a first system

using a handful of microservices. Deploy this system and use it in

production, expect to learn a lot about keeping it healthy and

ensuring the devops collaboration is working well. Give yourself

time to do this, learn from it, and grow more capability

before you ramp up your number of services.

If you don't have these capabilities now, you should ensure you

develop them so they are ready by the time you put a microservice

system into production. Indeed these are capabilities that you

really ought to have for monolithic systems too. While they aren't universally

present across software organizations, there are very few

places where they shouldn't be a high priority.

Going beyond a handful of services requires more. You'll need to

trace business transactions though multiple services and

automate your provisioning and deployment by fully embracing

ContinuousDelivery. There's also the shift to product

centered teams that needs to be started. You'll need to organize

your development environment so developers can easily swap between

multiple repositories, libraries, and languages. Some of my contacts are

sensing that there could be a useful MaturityModel here that can

help organizations as they take on more microservice implementations -

we should see more conversation on that in the next few years.

Acknowledgements

This list originated in discussions with my ThoughtWorks

colleagues, particularly those who attended the microservice

summit earlier this year. I then structured and finalized the

list in discussion with Evan Bottcher, Thiyagu Palanisamy, Sam

Newman, and James Lewis.

And as usual there were valuable

comments from our internal mailing list from Chris Ford, Keif

Morris, Premanand Chandrasekaran, Rebecca Parsons, Sarah

Taraporewalla, and Ian Cartwright.

August 27, 2014

Retreaded: CourtesyImplementation

Retread of post orginally made on 12 Aug 2004

When you a write a class, you mostly strive to ensure that the

features of that class make sense for that class. But there are

occasions when it makes sense to add a feature to allow a class to

conform to a richer interface that it naturally should.

The most common and obvious example of this is one that comes up

when you use the composite pattern. Let's consider a simple example

of containers. You have boxes which can contain other boxes and

elephants (that's an advantage of virtual elephants.) You want

to know how many elephants are in a box, considering that you need

to count the elephants inside boxes inside boxes inside the box. The

solution, of course, is a simple recursion.

# Ruby

class Node

end

class Box < Node

def initialize

@children = []

end

def << aNode

@children << aNode

end

def num_elephants

result = 0

@children.each do |c|

if c.kind_of? Elephant

result += 1

else

result += c.num_elephants

end

end

return result

end

end

class Elephant < Node

end

Now the kind_of? test in num_elephants is a smell, since we

should be wary of any conditional that tests the type of an

object. On the other hand is there an alternative? After all we are

making the test because elephants can't contain boxes or elephants, so it doesn't

make sense to ask them how many elephants are inside them. It

doesn't fit our model of the world to ask elephants how many

elephants they contain because they can't contain any. We might say

it doesn't model the real world, but my example feels a touch too

whimsical for that argument.

However when people use the composite pattern they often do

provide a method to avoid the conditional - in other words they do

this.

class Node

#if this is a strongly typed language I define an abstract

#num_elephants here

end

class Box < Node

def initialize

@children = []

end

def << aNode

@children << aNode

end

def num_elephants

result = 0

@children.each do |c|

result += c.num_elephants

end

return result

end

end

class Elephant < Node

def num_elephants

return 1

end

end

Many people get very disturbed by this kind of thing, but it does

a great deal to simplify the logic of code that sweeps through the

composite structure. I think of it as getting the leaf class

(elephant) to provide a simple implementation as a courtesy to its

role as a node in the hierarchy.

The analogy I like to draw is the definition of raising a number

to the power of 0 in mathematics. The definition is that any number

raised to the power of 0 is 1. But intuitively I don't think it

makes sense to say that any number multiplied by itself 0 times is

1 - why not zero? But the definition makes all the mathematics work

out nicely - so we suspend our disbelief and follow the definition.

Whenever we build a model we are designing a model to suit how we

want to perceive the world. Courtesy Implementations are worthwhile

if they simplify our model.

reposted on 27 Aug 2014

August 26, 2014

Bliki: MaturityModel

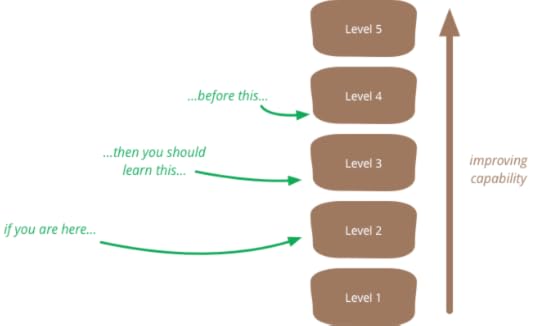

A maturity model is a tool that helps people assess the current

effectiveness of a person or group and supports figuring out what

capabilities they need to acquire next in order to improve their

performance. In many circles maturity models have gained a bad

reputation, but although they can easily be misused, in proper hands

they can be helpful.

Maturity models are structured as a series of levels of

effectiveness. It's assumed that anyone in the field will pass

through the levels in sequence as they become more capable.

So a whimsical example might be that of mixology (a fancy term

for someone who makes cocktails). We might define levels like

this:

Knows how to make a dozen basic drinks (eg "make me a Manhattan")

Knows at least 100 recipes, can substitute ingredients (eg

"make me a Vieux Carre in a bar that lacks Peychaud's")

Able to come up with cocktails (either invented or recalled)

with a few simple constraints on ingredients and styles (eg

"make me something with sherry and tequila that's moderately sweet").

Working with a maturity model begins with assessment, determining

which level the subject is currently performing in. Once you've

carried out an assessment to determine your level, then you use the

level above your own to prioritize what capabilities you need to

learn next. This prioritization of learning is really the big

benefit of using a maturity model. It's founded on the notion that

if you are at level 2 in something, it's much more important to

learn the things at level 3 than level 4. The model thus acts as

guide to what to learn, putting some structure on what otherwise

would be a more complex process.

The vital point here is that the true outcome of a maturity model

assessment isn't what level you are but the list of things you need

to work on to improve. Your current level is merely a piece of

intermediate work in order to determine that list of skills to

acquire next.

Any maturity model, like any model, is a simplification: wrong

but hopefully useful. Sometimes even a crude model can help you

figure out what the next step is to take, but if your needed mix of

capabilities varies too much in different contexts, then this form

of simplification isn't likely to be worthwhile.

A maturity model may have only a single dimension, or may have

multiple dimensions. In this way you might be level 2 in 19th

century cocktails but level 3 in tiki drinks. Adding dimensions

makes the model more nuanced, but also makes it more complex - and

much of the value of a model comes from simplification, even if it's

a bit of an over-simplification.

As well as using a maturity model for prioritizing learning, it

can also be helpful in the investment decisions involved. A maturity

model can contain generalized estimates of progress, such as "to get

from level 4 to 5 usually takes around 6 months and a 25%

productivity reduction". Such estimates are, of course, as crude as

the model, and like any estimation you should only use it when you have a

clear PurposeOfEstimation. Timing estimates can also be

helpful in dealing with impatience, particularly with level changes

that take many months. The model can help structure such

generalizations by being applied to past work ("we've done 7 level

2-3 shifts and they took 3-7 months").

Most people I know in the software world treat maturity models

with an inherent feeling of disdain, most of which you can understand

by looking at the Capability

Maturity Model (CMM) - the best known maturity

model in the software world. The disdain for the CMM sprung from two

main roots. The first problem was the CMM was very much associated

with a document-heavy, plan-driven culture which was very much in

opposition to the agile software community.

But the more serious problem with the CMM was the corruption of

its core value by certification. Software development companies

realized that they could gain a competitive advantage by having

themselves certified at a higher level than their competitors - this

led to a whole world of often-bogus certification levels,

levels that lacked a CertificationCompetenceCorrelation. Using a

maturity model to say one group is better than another is a classic

example of ruining an informational metric by incentivizing it. My

feeling that anyone doing an assessment should never publicize the

current level outside of the group they are working with.

It may be that this tendency to compare levels to judge worth is a

fundamentally destructive feature of a maturity model, one that will

always undermine any positive value that comes from it. Certainly it

feels too easy to see maturity models as catnip for consultants

looking to sell performance improvement efforts - which is why

there's always lots of pushback on our internal mailing list whenever

someone suggests a maturity model to add some structure to our

consulting work.

In an email discussion over a draft of this article, Jason Yip

observed a more fundamental problem with maturity models:

"One of my

main annoyances with most maturity models is not so much that

they're simplified and linear, but more that they're suggesting a

poor learning order, usually reflecting what's easier to what's

harder rather than you should typically learn following this

path, which may start with some difficult things.

In other words,

the maturity model conflates level of effectiveness with

learning path"

Jason's observation doesn't mean maturity models are never a good

idea, but they do raise extra questions when assessing their

fitness. Whenever you use any kind of model to understand a

situation and draw inferences, you need to first ensure that the

model is a good fit to the circumstances. If the model doesn't fit,

that doesn't mean it's a bad model, but it does mean it's

inappropriate for this situation. Too often, people don't put enough

care in evaluating the fitness of a model for a situation before

they leap to using it.

Acknowledgements

Jeff Xiong reminded me that a model can be helpful for investment

decisions. Sriram Narayan and Jason Yip contributed some helpful feedback.

August 23, 2014

photostream 72

August 14, 2014

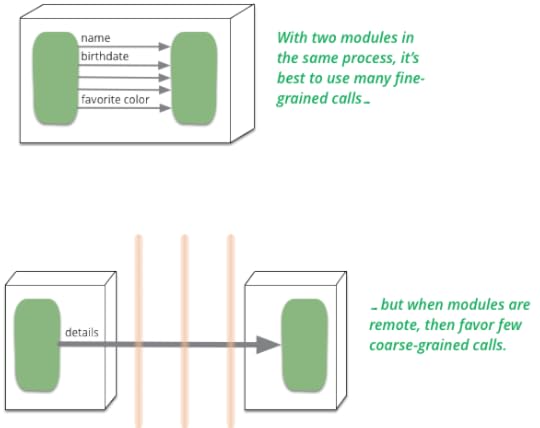

Microservices and the First Law of Distributed Objects

When I wrote Patterns of Enterprise Application Architecture, I

coined what I called the First Law of Distributed Object Design:

“don’t distribute your objects”. In recent months there’s been a lot

of interest in microservices, which has led a few people to ask

whether microservices are in contravention to this law, and if so

why I am in favor of them?

Martin Fowler's Blog

- Martin Fowler's profile

- 1103 followers