Martin Fowler's Blog, page 35

February 8, 2015

photostream 82

February 7, 2015

Bliki: DataLake

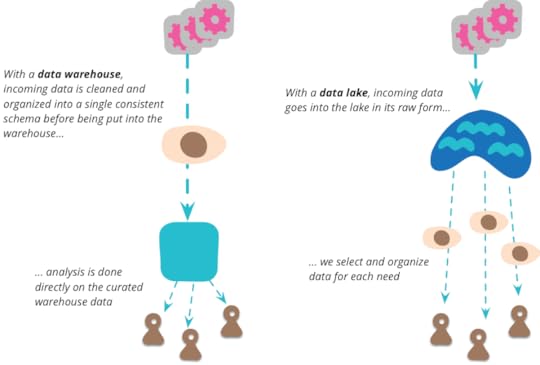

Data Lake is a term that's appeared in this decade to describe

an important component of the data analytics pipeline in the world of

Big Data. The idea is to

have a single store for all of the raw data that anyone in an

organization might need to analyze. Commonly people use

Hadoop to work on the data in the lake, but the concept is broader

than just Hadoop.

When I hear about a single point to pull together all the data

an organization wants to analyze, I immediately think of the notion

of the data warehouse (and data

mart [1]). But there is a vital distinction between the

data lake and the data warehouse. The data lake stores raw

data, in whatever form the data source provides. There is no

assumptions about the schema of the data, each data source can use

whatever schema it likes. It's up to

the consumers of that data to make sense of that data for their own

purposes.

This is an important step, many data warehouse initiatives didn't

get very far because of schema problems. Data warehouses tend to

go with the notion of a single schema for all analytics needs, but

I've taken the view that a single unified data model is impractical

for anything but the smallest organizations. To model even a

slightly complex domain you need multiple

BoundedContexts, each with its own data model. In

analytics terms, you need each analytics user to use a model that

makes sense for the analysis they are doing. By shifting to storing

raw data only, this firmly puts the responsibility on the data

analyst.

Another source of problems for data warehouse initiatives is

ensuring data quality. Trying to get an authoritative single source

for data requires lots of analysis of how the data is acquired and

used by different systems. System A may be good for some data, and

system B for another. You run into rules where system A is better

for more recent orders but system B is better for orders of a month

or more ago, unless returns are involved. On top of this, data

quality is often a subjective issue, different analysis has

different tolerances for data quality issues, or even a different

notion of what is good quality.

This leads to a common criticism of the data lake - that it's just a

dumping ground for data of widely varying quality, better named a

data swamp. The criticism is both valid and irrelevant. The hot

title of the New Analytics is "Data Scientist". Although it's a

much-abused title, many of these folks do have a solid background in

science. And any serious scientist knows all about data quality

problems. Consider what you might think is the simple matter of analyzing temperature readings

over time. You have to take into account that some weather stations

are relocated in ways that may subtly affect the readings, anomalies due to problems

in equipment, missing periods when the sensors aren't working. Many

of the sophisticated statistical techniques out there are created

to sort out data quality problems. Scientists are always skeptical about

data quality and are used to dealing with questionable data. So for

them the lake is important because they get to work with raw data

and can be deliberate about applying techniques to make sense of it,

rather than some opaque data cleansing mechanism that probably does

more harm that good.

Data warehouses usually would not just cleanse but also aggregate

the data into a form that made it easier to analyze. But scientists

tend to object to this too, because aggregation implies throwing

away data. The data lake should contain all the data because you

don't know what people will find valuable, either today or in a

couple of years time.

One of my colleagues illustrated this thinking with a recent

example: "We were trying to

compare our automated predictive models versus manual forecasts made

by the company's contract managers. To do this we decided to train

our models on data only up to about a year ago and compare the

predictions to the ones made by managers at that same time. We now

know the correct results so this should be good test of accuracy.

When we started to do this it appeared that the manager's predictions

were horrible and that even our simple models, made in just two weeks,

were crushing them. We suspected that this was too good (for us) to be

true. After a lot of testing and digging we discovered that the time

stamps associated with those manager predictions were not correct.

They were being modified by some end-of-month processing report. So in

short, these values in the data warehouse were useless and so we

feared that we would have no way of performing this comparison. After

more digging we found that these reports were stored somewhere where we

could get them and extract the real forecasts made at that time.

(We're crushing them again but it's taken many months to get there)."

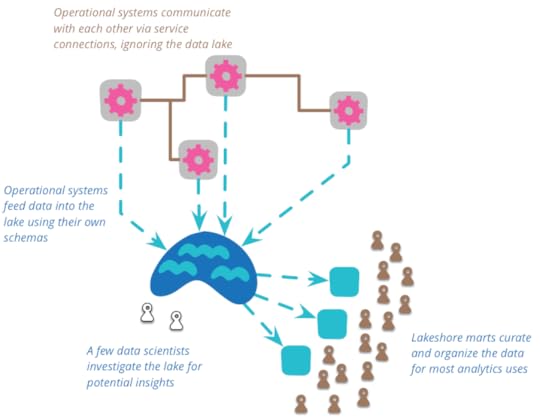

The complexity of this raw data means that there is room for

something that curates the data into a more manageable structure (as

well as reducing the considerable volume of data.) The data lake shouldn't be

accessed directly very much. Because the data is raw, you need a lot

of skill to make any sense of it. You have relatively few people who

work in the data lake, as they uncover generally useful views of

data in the lake, they can create a number of data marts each of which

has a specific model for a single bounded context. A larger number

of downstream users can then treat these lakeshore marts as an

authoritative source for that context.

So far I've described the data lake as singular point for

integrating data across an enterprise, but I should mention that

isn't how it was originally intended. The term was

coined by James Dixon in 2010, when he did that he intended a

data lake to be used for a single data source, multiple data sources

would instead form a "water garden". Despite its original formulation

the prevalent usage now is to treat a data lake as combining many

sources. [2]

You should use a data lake for analytic purposes, not for

collaboration between operational systems. When operational systems

collaborate they should do this through services designed for the

purpose, such as RESTful HTTP calls, or asynchronous messaging. The

lake is too complex to trawl for operational communication. It may

be that analysis of the lake can lead to new operational

communication routes, but these should be built directly rather than

through the lake.

It is important that all data put in the lake should have a clear

provenance in place and time. Every data item should have a clear

trace to what system it came from and when the data was produced.

The data lake thus contains a historical record. This might come

from feeding Domain Events

into the lake, a natural fit with Event Sourced systems. But it could

also come from systems doing a regular dump of current state into the

lake - an approach that's valuable when the source system doesn't

have any temporal capabilities but you want a temporal

analysis of its data. A consequence of this is that data put into

the lake is immutable, an observation once stated cannot be removed

(although it may be refuted later), you should also expect

ContradictoryObservations.

The data lake is schemaless, it's up to the source systems to

decide what schema to use and for consumers to work out how to deal

with the resulting chaos. Furthermore the source

systems are free to change their inflow data schemas at will, and

again the consumers have to cope. Obviously we prefer such changes

to be as minimally disruptive as possible, but scientists prefer messy

data to losing data.

Data lakes are going to be very large, and much of the storage is

oriented around the notion of a large schemaless structure - which

is why Hadoop and HDFS are usually the technologies people use for

data lakes. One of the vital tasks of the lakeshore marts is to

reduce the amount of data you need to deal with, so that big data analytics

doesn't have to deal with large amounts of data.

The Data Lake's appetite for a deluge of raw data raises awkward

questions about privacy and security. The principle of

Datensparsamkeit is very much in tension with the data

scientists' desire to capture all data now. A data lake makes a

tempting target for crackers, who might love to siphon choice bits

into the public oceans. Restricting direct lake access to a small

data science group may reduce this threat, but doesn't avoid the

question of how that group is kept accountable for the privacy of

the data they sail on.

Notes

1:

The usual distinction is that a data mart is for a single

department in an organization, while a data warehouse integrates

across all departments. Opinions differ on whether a data

warehouse should be the union of all data marts or whether a

data mart is a logical subset (view) of data in the data

warehouse.

2:

In a later blog post, Dixon emphasizes the lake versus water

garden distinction, but (in the comments) says that it is a

minor change. For me the key point is that the lake stores a

large body of data in its natural state, the number of feeder

streams isn't a big deal.

Acknowledgements

My thanks to

Anand Krishnaswamy, Danilo Sato, David Johnston, Derek Hammer, Duncan Cragg, Jonny Leroy, Ken

Collier, Shripad Agashe, and Steven Lowe

for discussing drafts of this post on our internal mailing lists

January 27, 2015

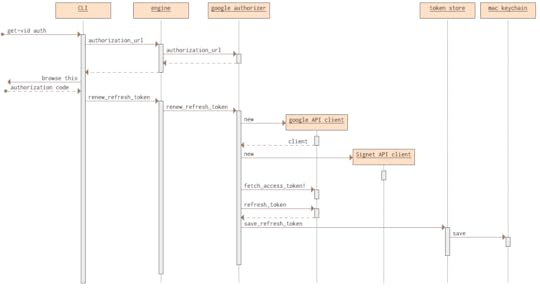

Using oauth for a simple command line script to access Google's data

I recently needed to write a simple script to pull some data

from a Google website. Since I was grabbing some private data, I

needed authorize myself to do that. I found it much more work than

I expected, not because it's hard, but because there wasn't much

documentation there to guide me - I had to puzzle out what path

to go based on lots of not particularly relevant documentation. So

once I'd figured it out I decided to write a short account of what

I'd done, partly in case I need to do this again, and partly to

help anyone else who wants to do this.

January 24, 2015

photostream 81

January 13, 2015

Bliki: DiversityMediocrityIllusion

I've often been involved in discussions about deliberately

increasing the diversity of a group of people. The most common case

in software is increasing the proportion of women. Two examples are

in hiring and conference speaker rosters where we discuss trying to

get the proportion of women to some level that's higher than usual.

A common argument against pushing for greater diversity is that it

will lower standards, raising the spectre of a diverse but mediocre

group.

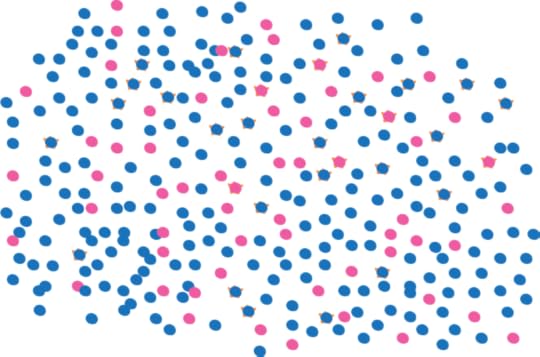

To understand why this is an illusionary concern, I like to

consider a little thought experiment. Imagine a giant bucket that

contains a hundred thousand marbles. You know that 10% of these

marbles have a special sparkle that you can see when you carefully

examine them. You also know that 80% of these marbles are blue and

20% pink, and that sparkles exist evenly across both colors [1]. If you were

asked to pick out ten sparkly marbles, you know you could

confidently go through some and pick them out. So now imagine you're

told to pick out ten marbles such that five were blue and five were

pink.

I don't think you would react by saying “that's impossible”.

After all there are two thousand pink sparkly marbles in there,

getting five of them is not beyond the wit of even a man. Similarly

in software, there may be less women in the software business, but

there are still enough good women to fit the roles a company or a

conference needs.

The point of the marbles analogy, however, is to focus on the

real consequence of the demand for 50:50 split. Yes it's possible to

find the appropriate marbles, but the downside is that it takes

longer. [2]

That notion applies to finding the right people too. Getting

a better than base proportion of women isn't impossible, but it does

require more work, often much more work. This extra effort

reinforces the rarity, if people have difficulty finding good

people as it is, it needs determined effort to spend the extra time

to get a higher proportion of the minority group — even if you are

only trying to raise the proportion of women up to 30%, rather than

a full 50%.

In recent years we've made increasing our diversity a high

priority at ThoughtWorks. This has led to a lot of effort trying to

go to where we are more likely to run into the talented women we are

seeking: women's colleges, women-in-IT groups and conferences. We

encourage our women to speak at conferences, which helps let other

women know we value a diverse workforce.

When interviewing, we make a point of ensuring there are women

involved. This gives women candidates someone to relate to, and

someone to ask questions which are often difficult to ask men. It's

also vital to have women interview men, since we've found that women

often spot problematic behaviors that men miss as we just don't have

the experiences of subtle discriminations. Getting a diverse group

of people inside the company isn't just a matter of recruiting, it

also means paying a lot of attention to the environment we have, to try to

ensure we don't have the same AlienatingAtmosphere that

much of the industry exhibits. [3]

One argument I've heard against this approach is that if everyone

did this, then we would run out of pink, sparkly marbles. We'll know

this is something to be worried about when women are paid

significantly more than men for the same work.

One anecdote that stuck in my memory was from a large,

traditional company who wanted to improve the number of women in

senior management positions. They didn't impose a quota on

appointing women to those positions, but they did impose a quota for

women on the list of candidates. (Something like: "there must be at

least three credible women candidates for each post".) This

candidate quota forced the company to actively seek out women

candidates. The interesting point was that just doing this, with no

mandate to actually appoint these women, correlated with an increased

proportion of women in those positions.

For conference planning it's a similar strategy: just putting out a call for

papers and saying you'd like a diverse speaker lineup isn't enough.

Neither are such things as blind review of proposals (and I'm not

sure that's a good idea anyway). The important thing is to seek out

women and encourage them to submit ideas. Organizing conferences is

hard enough work as it is, so I can sympathize with those that don't

want to add to the workload, but those that do can get there. FlowCon

is a good example of a conference that made this an explicit

goal and did far better than the industry average (and in case you

were wondering, there was no

difference between men's and women's evaluation scores).

So now that we recognize that getting greater diversity is a

matter of application and effort, we can ask ourselves whether the

benefit is worth the cost. In a broad professional sense, I've

argued that it is, because our DiversityImbalance is

reducing our ability to bring the talent we need into our profession,

and reducing the influence our profession needs to have on society.

In addition I believe there is a moral argument to push back against

long-standing wrongs faced by

HistoricallyDiscriminatedAgainst groups.

Conferences have an important role to play in correcting this

imbalance. The roster of speakers is, at least subconsciously, a

statement of what the profession should look like. If it's all white

guys like me, then that adds to the AlienatingAtmosphere

that pushes women out of the profession. Therefore I believe that

conferences need to strive to get an increased proportion of

historically-discriminated-against speakers. We, as a profession,

need to push them to do this. It also means that women have an

extra burden to become visible and act as part of that better

direction for us. [4]

For companies, the choice is more personal. For me,

ThoughtWorks's efforts to improve its diversity are a major factor

in why I've been an employee here for over a decade. I don't think

it's a coincidence that ThoughtWorks is also a company that has a

greater open-mindedness, and a lack of political maneuvering, than most of the

companies I've consulted with over the years. I consider those

attributes to be a considerable competitive advantage in attracting

talented people, and providing an environment where we can

collaborate effectively to do our work.

But I'm not holding ThoughtWorks up as an example of perfection.

We've made a lot of progress over the decade I've been here, but we

still have a long way to go. In particular we are very short of

senior technical women. We've introduced a number of programs around

networks, and leadership development, to help grow women

to fill those gaps. But these things take time - all you have to do

is look at our Technical Advisory Board

to see that we are a long way from the ratio we seek.

Despite my knowledge of how far we still have to climb, I can

glimpse the summit ahead. At a recent AwayDay in Atlanta I was

delighted to see how many younger technical women we've managed to

bring into the company. While struggling to keep my head above water

as the sole male during a late night game of Dominion, I enjoyed a

great feeling of hope for our future.

Notes

1:

That is 10% of blue marbles are sparkly as are 10% of pink.

2:

Actually, if I dig around for a while in that bucket, I find

that some marbles are neither blue nor pink, but some

engaging mixture of the two.

3:

This is especially tricky for a company like us, where so much

of our work is done in client environments, where we aren't able

to exert as much of an influence as we'd like. Some of our

offices have put together special training to educate both sexes

on how to deal with sexist situations with clients. As a man, I

feel it's important for me to know how I can be supportive, it's

not something I do well, but it is something I want to learn to improve.

4:

Many people find the pressure of public speaking intimidating

(I've come to hate it, even with all my practice). Feeling that

you're representing your entire gender or race only makes it

worse.

Acknowledgements

Camila Tartari, Carol Cintra, Dani Schufeldt, Derek Hammer, Isabella

Degen, Korny Sietsma, Lindy Stephens, Mridula Jayaraman, Nikki

Appleby, Rebecca Parsons, Sarah Taraporewalla, Stefanie Tinder, and Suzi

Edwards-Alexander

commented on

drafts of this article.

January 9, 2015

An example of preparatory refactoring

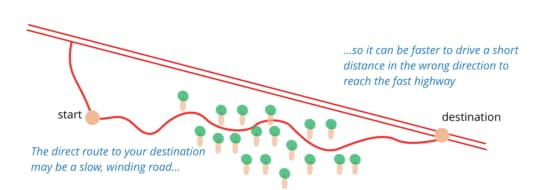

There are various ways in which refactoring can fit into our

programming workflow. One useful notion is that of Preparatory

Refactoring. This is where I'm adding a new feature, and I see

that the existing code is not structured in such a way that

makes adding the feature easy. So first I refactor the code into

the structure that makes it easy to add the feature, or as Kent

Beck pithily put it "make the change easy, then make the easy

change".

It always helps to use examples to explain things, and

so I took the opportunity when I ran into a case while adding a

new feature to my publication toolchain.

Interview on internet privacy with Erik Dörnenburg, Ola Bini, and Tim Bray

At goto Aarhus this year, there was a theme on internet

privacy. Tim Bray gave a keynote on the state of

browsers which touched on this issue and later gave a full

conference talk on the state of internet

privacy and security. Erik Dörnenburg and I gave a keynote

explaining why we feel it is the responsibility of

developers to defeat mass surveillance. Our colleague Ola

Bini, who is very active in the internet security world himself,

felt this was a good opportunity to get all of us together to discuss

these issues in an interview.

December 20, 2014

photostream 80

December 19, 2014

Agile Architecture

A couple of weeks ago I did a joint talk with my colleague Molly Bartlett Dishman about the interaction of agile software development and application architecture. We talk how these two activities overlap, explaining that architecture is a vital part of a successful agile project. We then move on to passing on tips for how to ensure that the architecture work is happening.

This talk was part of ThoughtWorks’s “Rethink” event in Dallas. There are also excellent talks by Brandon Byars on how enterprises should be restructured to take advantage of agile thinking and by “Pragmatic” Dave Thomas on the dangers of “agile” being co-opted by the big-methodology crowd that it was designed to oppose. (The latter is worth it just to enjoy Dave in a suit and tie.)

Molly and I will be reprising and updating our talk for the O’Reilly Architecture conference in March next year.

December 17, 2014

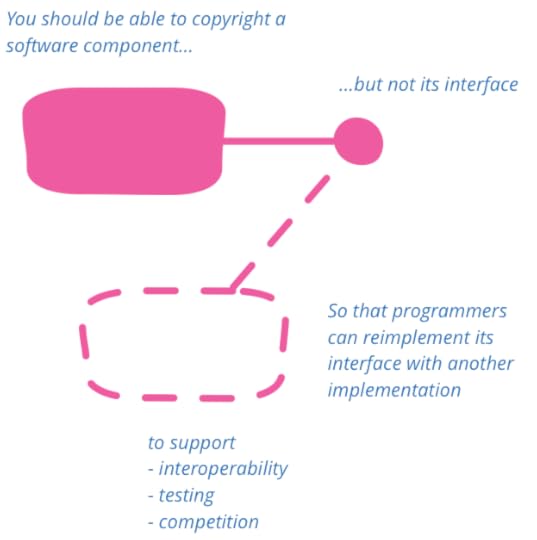

APIs should not be copyrightable

Last month, the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF)

filed

an amicus brief with the Supreme Court of the United States, asking the

justices to review an earlier lower court decision that allows

APIs (Application Programming Interfaces) to be copyrightable. I'm

one of the 77 software professionals who signed the brief,

although rather intimidated by a group that includes Abelson &

Sussman, Aho & Ullman, Josh Bloch, Fred Brooks, Vint Cerf,

Peter Deutsch, Mitch Kapor, Alan Kay, Brian Kernighan, Barbara

Liskov, Guido van Rossum, Bruce Schneier, and Ken Thompson.

The original lawsuit was brought by Oracle against Google,

claiming that Oracle held a copyright on the Java APIs, and that

Google infringed these APIs when they built Android. My support in

this brief has nothing to do with the details of the dispute

between these two tech giants, but everything to do with the

question of how intellectual property law should apply to

software, particularly software interfaces.

I'm not part of the thinking that asserts that nothing in

software should be intellectual property. While I do think that

software patents are inherently

broken, copyright is a good mechanism to allow software

authors to have some degree of control over of what happens with their hard work.

Software has always been a tricky source of income, because

it's trivial to copy. Copyright provides a legal basis to control at least

some copying. Without something like this, it

becomes very hard for someone to work on creating things and still

be able to pay the mortgage. While we all like free stuff, I think

it's only fair to give people the chance to earn a living from the

work they do.

But any intellectual property mechanism has to balance this

benefit with the danger that excessive intellectual property

restrictions can impede further innovation, whether that be

extending an invention, or reimagining a creative work. As a

result, patent and copyright regimes have some form of limitation

built in. One limitation is one of time: patents and copyrights

expire (although the Mickey Mouse

discontinuity is threatening that).

Interfaces are how things plug together. An example from the

physical world is cameras with interchangeable lenses. Many camera

makers don't encourage other companies to make lenses for their

cameras, but such third-party companies can reverse-engineer how

the interface works and build a lens that will mount on a camera.

We regularly see this happen with third-party parts providers -

and these third parties do a great deal to provide lower costs and

features that the main company doesn't support. I used a Sigma

lens with my Canon camera because Canon didn't (at the time)

make an 18-200mm lens. I've bought third party batteries for

cameras because they're cheaper. Similarly I've repaired my car with third party

parts again to lower costs or get an audio system that better

matched my needs.

Software interfaces are much the same, and the ability to

extend open interfaces, or reverse-engineer interfaces, has played

a big role in advancing software systems. Open interfaces were a

vital part of allowing the growth of the internet, nobody has to

pay a copyright licence to build a HTTP server, nor to connect to

one. The growth of Unix-style operating systems relied greatly on

the fact that although much of the source code for AT&T's Unix

was copyrighted, the interfaces were not. This allowed offshoots

such as BSD and Linux to follow Unix's interfaces, which helped

these open-source systems to get traction by making it easier for

programs built on top of Unix to interact with new

implementations.

A picture is worth a 1000 words, so here's a picture of some books written by signatories of the EFF amicus brief -- Josh Bloch

The story of SMB and Samba is a good example of how

non-copyrightable APIs spurred competition. When Windows became a

dominent desktop operating system, its SMB protocol dominated

simple networks. If non-windows computers wanted to communicate

effectively with the dominant windows platform, they needed to

talk to SMB. Microsoft didn't provide any documentation to help

competitors do this, since an inability to communicate with SMB

was a barrier to their competitors. However, Andrew Tridgell was

able to deduce the specification for SMB and build an

implementation for Unix, called Samba. By using Samba non-windows

computers could collaborate on a network, thus encouraging the

competition from Mac and Linux based systems. A similar story

happened years before with the IBM BIOS, which was

reverse-engineered by competitors.

The power of a free-market system comes from competition, the

notion that if I can find a way to bake bread that's either

cheaper or tastier than my local bakers, I can start a bakery and

compete with them. Over time my small bakery can grow and compete

with the largest bakers. For this to work, it's vital that we

construct the market so that existing players that dominate the

market cannot build barriers to prevent new people coming in with

innovations to reduce cost or improve quality.

Software interfaces are critical points for this with software.

By keeping interfaces open, we encourage a competitive

marketplace of software systems that encourage innovation to

provide more features and reduce costs. Closing this off will

lead to incompatible islands of computer systems, unable to

communicate.

Such islands of incompatibility present a considerable barrier

to new competitors, and are bad for that reason alone. But it's

they are bad for users too. Users value software

that can work together, and even if the various vendors of

software aren't interested in communication, we should encourage

other providers to step in and fill the gaps. Tying systems

together requires open interfaces, so that integrators can safely

implement an interface in order to create communication links. We

value standard connectors in the physical world, and while

software connections are often too varied for everything to be

standardized, we shouldn't use copyright law to add further hurdles.

The need to implement interfaces also goes much deeper than

this. As programmers we often have to implement interfaces defined

outside our code base in order to do our jobs. It's common to have

to modify software that was written with one library in mind to

work with another - a useful way to do this is to write adapters that implement the interface of the

that implement the interface of the

first library by forwarding the second. Implementing interfaces is

also vital in testing, as it allows you to create Test Doubles.

So for the sake of our ability to write programs properly, our

users' desire to have software work together, and for society's

desire for free markets that spur competition — copyright should

not be used for APIs.

Acknowledgements

Derek Hammer raised the point that implementing interfaces

for adapters and testing is a regular part of programming.

Andy Slocum, Jason Pfetcher, Jonathan Reyes, Josh Bloch, and

Michael Barclay

commented on drafts of this article. Extra thanks to Josh Bloch for

helping to organize the 77 of us who signed the brief.

Martin Fowler's Blog

- Martin Fowler's profile

- 1104 followers