Martin Fowler's Blog, page 32

August 30, 2015

photostream 89

August 27, 2015

Citizen Four

My brief thoughts on watching my newly acquired DVD of

Citizen Four - a film about the whistleblower Edward Snowden.

August 26, 2015

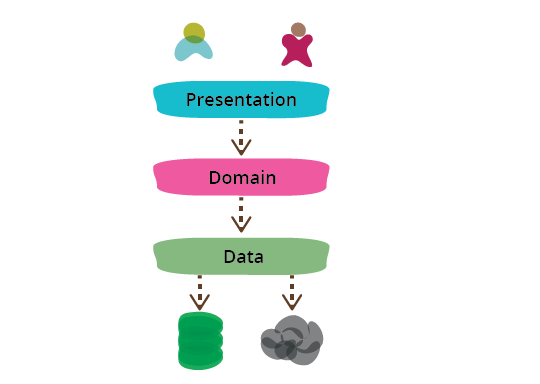

Bliki: PresentationDomainDataLayering

One of the most common ways to modularize an information-rich

program is to separate it into three broad layers: presentation (UI), domain logic

(aka business logic), and data access. So you often see web

applications divided into a web layer that knows about handling http

requests and rendering HTML, a business logic layer that contains

validations and calculations, and a data access layer that

sorts out how to manage persistant data in a database or remote

services.

On the whole I've found this to be an effective form of

modularization for many applications and one that I regularly use

and encourage. It's biggest advantage (for me) is that it allows me

to reduce the scope of my attention by allowing me to think about the

three topics relatively independently. When I'm working on domain

logic code I can mostly ignore the UI and treat any interaction with

data sources as an abstract set of functions that give me the data I

need and update it as I wish. When I'm working on the data access

layer I focus on the details of wrangling the data into the form

required by my interface. When I'm working on the presentation I can

focus on the UI behavior, treating any data to display or update as

magically appearing by function calls. By separating these elements

I narrow the scope of my thinking in each piece, which makes it

easier for me to follow what I need to do.

This narrowing of scope doesn't imply any sequence to programming them - I usually find I need to

iterate between the layers. I might build the data and domain layers

off my initial understanding of the UX, but when refining the UX I

need to change the domain which necessitates a change to the data

layer. But even with that kind of cross-layer iteration, I find it

easier to focus on one layer at a time as I make changes. It's

similar to the switching of thinking modes you get with

refactoring's two hats.

Another reason to modularize is to allow me to substitute

different implementations of modules. This separation

allows me to build multiple presentations on top of the same domain

logic without duplicating it. Multiple presentations could be

separate pages in a web app, having a web app plus mobile native

apps, an API for scripting purposes, or even an old fashioned

command line interface. Modularizing the data source allows me to

cope gracefully with a change in database technology, or to support

services for persistance that may change with little notice. However

I have to mention that while I often hear about data access

substitution being a driver for separating the data source layer, I

rarely hear of someone actually doing it.

Modularity also supports testability, which naturally appeals to

me as a big fan of SelfTestingCode. Module boundaries

expose seams that are good affordance for testing. UI code is

often tricky to test, so it's good to get as much logic as you can

into a domain layer which is easily tested without having to do

gymnastics to access the program through a UI [1]. Data access is often slow and awkward, so using

TestDoubles around the data layer often makes domain logic

testing much easier and responsive.

While substitutability and

testability are certainly benefits of this layering, I must stress that even

without either of these reasons I would still divide into layers

like this. The

reduced scope of attention reason is sufficient on its own.

When talking about this we can either look at it as one pattern

(presentation-domain-data) or split it into two patterns

(presentation-domain, and domain-data). Both points of view are

useful - I think of presentation-domain-data as a composite of

presentation-domain and domain-data.

I consider these layers to be a form of module, which is a

generic word I use for how we clump our software into relatively

independent pieces. Exactly how this corresponds to code depends on

the programming environment we're in. Usually the lowest level is

some form of subroutine or function. An object-oriented language

will have a notion of class that collects functions and data

structure. Most languages have some form of higher level called

packages or namespaces, which often can be formed into a hierarchy.

Modules may correspond to separately deployable units: libraries,

or services, but they don't have to.

Layering can occur at any of these levels. A small program may

just put separate functions for the layers into different files. A

larger system may have layers corresponding to namespaces with many

classes in each.

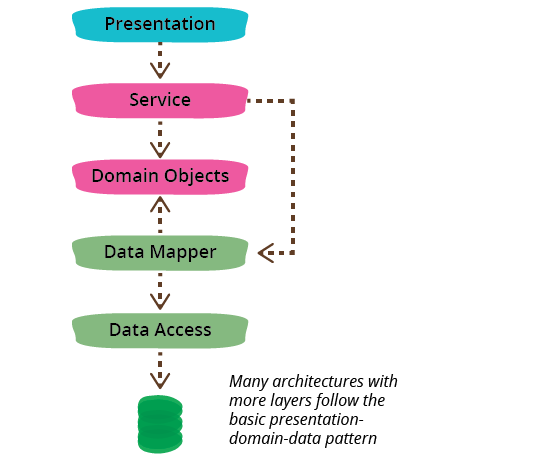

I've mentioned three layers here, but it's common to see

architectures with more than three layers. A common variation is to

put a service layer between the domain and presentation, or to

split the presentation layer into separate layers with something like

Presentation Model. I don't

find that more layers breaks the essential pattern, since the core

separations still remain.

The dependencies generally run from top to bottom through the

layer stack: presentation depends on the domain, which then depends

on the data source. A common variation is to arrange things so that

the domain does not depend on its data sources by introducing a mapper between the domain and

data source layers. This approach is often referred to as a Hexagonal

Architecture.

Although presentation-domain-data separation is a common

approach, it should only be applied at a relatively small granularity.

As an application grows, each layer can get sufficiently complex on

its own that you need to modularize further. When this happens it's

usually not best to use presentation-domain-data as the higher

level of modules. Often frameworks encourage you to have

something like view-model-data as the top level namespaces; that's

ok for smaller systems, but once any of these layers gets too big

you should split your top level into domain oriented modules which

are internally layered.

Developers don't have to be full-stack but teams should be.

One common way I've seen this layering lead organizations astray

is the AntiPattern of separating development teams by

these layers. This looks appealing because front-end and back-end

development require different frameworks (or even languages) making

it easy for developers to specialize in one or the other. Putting

those people with common skills together supports skill

sharing and allows the organization to treat the team as a provider

of a single, well-delineated type

of work. In the same way, putting all the database specialists

together fits in with the common centralization of databases and

schemas.

But the rich interplay between these layers

necessitates frequent swapping between them. This isn't too hard

when you have specialists in the same team who can casually

collaborate, but team boundaries add considerable friction, as well

as reducing an individual's motivation to develop the important cross-layer

understanding of a system.

Worse, separating the layers into teams adds distance between developers and users.

Developers don't have to be full-stack (although that is

laudable) but teams should be.

Further Reading

I've written about this separation from a number of different

angles elsewhere. This layering drives the structure of P of EAA and chapter 1 of that book talks

more about this layering. I didn't make this layering a pattern in

its own right in that book but have toyed with that territory with

Separated

Presentation and PresentationDomainSeparation.

For more on why presentation-domain-data shouldn't be the

highest level modules in a larger system, take a look at the

writing and speaking of Simon Brown. I also

agree with him that software architecture should be embedded in

code.

I had a fascinating

discussion with my colleague Badri Janakiraman about the

nature of hexagonal architectures. The context was mostly around

applications using Ruby on Rails, but much of the thinking applies

to other cases when you may be considering this approach.

Acknowledgements

James Lewis, Jeroen Soeters, Marcos Brizeno, Rouan Wilsenach, and

Sean Newham

discussed drafts of this post with me.

Notes

1:

A PageObject is also an important tool to help

testing around UIs.

Share:

if you found this article useful, please share it. I appreciate the feedback and encouragement

August 25, 2015

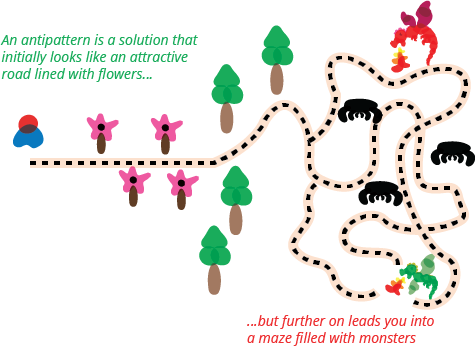

Bliki: AntiPattern

Andrew Koenig first coined the term "antipattern" in an article

in JOOP[1], which is sadly not available on the internet. The essential

idea (as I remember it [2]) was that an antipattern was something that

seems like a good idea when you begin, but leads you into trouble.

Since then the term has often been used just to indicate any bad

idea, but I think the original focus is more useful.

In the paper Koenig said

An antipattern is just like a pattern, except that instead of a

solution it gives something that looks superficially like a

solution but isn't one.

-- Andrew Koenig

This is what makes a good antipattern something separate

to just a bad thing to point and laugh at. The fact that it looks

like a good solution is its essential danger. Since it looks good,

sensible people will be take the path - only once you've put a

lot of effort into it will you know it's bad result.

When writing a description of an antipattern

it's valuable to describe how to get out of trouble if

you've taken the bad path. I see that as useful

but not necessary. If there's no good

way to get out of it, that doesn't reduce the value of the

warning.

It's useful to remember that the same solution can be a good

pattern in some contexts and an antipattern in others. The value

of a solution depends on the context that you use it.

Notes

1:

Journal of Object-Oriented Programming, Vol 8, no. 1.

March/April 1995. It was then reprinted in "The Patterns

Handbook", edited by Linda Rising (Cambridge University Press)

2:

I don't have a copy of the paper, so I'm going primarily off

memory and some old notes.

Share:

if you found this article useful, please share it. I appreciate the feedback and encouragement

August 18, 2015

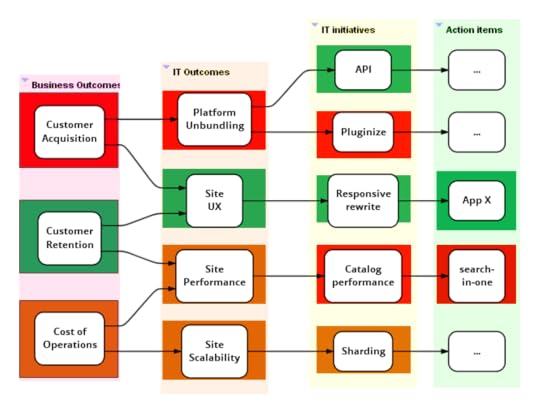

Bliki: AlignmentMap

Alignment maps are organizational information radiators that help

visualize the alignment of ongoing work with business outcomes. The

work may be regular functionality addition or technical work such as

re-architecting or repaying technical debt or improving the build

and deployment pipeline. Team members use alignment maps to

understand what business outcomes their day-to-day work is meant to

improve. Business and IT sponsors use them to understand how ongoing

work relates to the business outcomes they care about.

Here’s an

example scenario (inspired by real life) that illustrates how these

maps may be useful. A team of developers had inefficiently implemented a

catalog search function as N+1 calls. The first call to the catalog

index returned a set of SKU IDs. For each ID returned, a query was

then made to retrieve product detail. The implementation came to the

attention of an architect when it failed performance tests. He advised

the team to get rid of the N+1 implementation.

“Search-in-one” was the mantra he offered the team as a way to

remember their objective. Given the organizational boundary between

architects and developers and the low frequency of communication

between them, the mantra was taken literally. The team moved heaven

and earth to implement a combined index query and detail query in a single

call. They lost sight of the real objective of improving search

performance and slogged away in an attempt to achieve acceptable

performance in exactly one call. Funding ran out in a few months and

after some heated discussions, the project was cancelled and the team

disbanded.

The above example may seem absurd but sadly, enterprise IT is

no stranger to architecture and business projects that are

cancelled after a while because they lost sight of why they were

funded in the first place. In the terminology of organizational

design, these are problems of alignment.

Visualizing Alignment

Broadly, IT strategy has to align with business strategy and

IT outcomes with desired business outcomes. A business outcome

may be supported (in part) by one or more IT outcomes. Each IT

outcome may be realized by one or more initiatives (program of

work—architectural or business). At this point, it may also be

useful to identify an owner for each initiative who then sponsors

work (action items) across multiple teams as part of executing

the initiative. Depending on the initiative the owner may be a

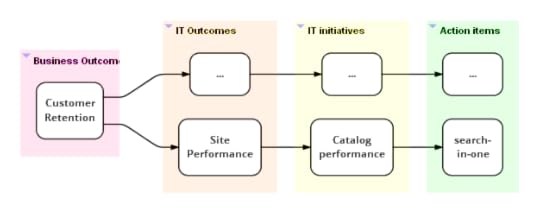

product owner, architect, tech lead or manager. Here's an

alignment map for the “search-in-one” case. Had it been in public

display in the team’s work area, it might have prompted someone

to take a step back and ask what their work was really meant to

achieve.

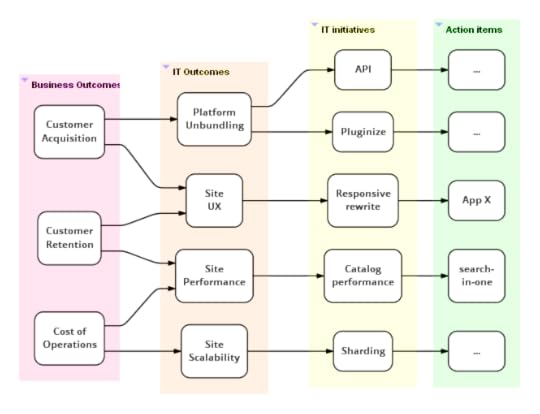

Global Map

A global alignment map for the IT (appdev+ops) organization may

look more like this (although real maps tend to be much

larger).

As with all information radiators, such a map is a

snapshot in time and needs to be updated regularly (say once a

month). Each team displays a big printout of the global map in its

work area.

Big organizations are likely to realize value early in this

exercise by collaborating to come up with a version 1.0 of such a

map that everyone agrees to. The discussions around who owns what

initiatives and what outcomes an initiative contributes to leads

to a fair bit of organizational clarity of what everyone is up to.

Usually, the absence of well-articulated and commonly understood

business and IT strategies come in the way of converging on a set

of business and IT outcomes. Well-facilitated workshops with deep and wide participation

across the relevant parts of the organization can help address this.

Tracing alignment paths

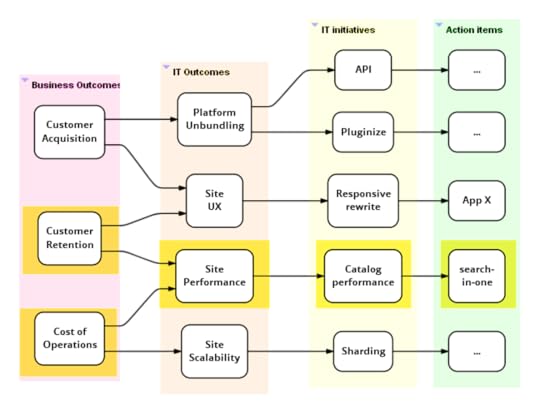

Once a global alignment map is in place, it allows us to trace

alignment from either end. IT and business sponsors can trace what

action items are in play under a given initiative. Development

team members can trace through the map to understand the real

purpose of items they are working on. In addition to in-progress

items, we could also include action items that are planned, done

or blocked.

As illustrated in the map above, each team highlights their section

of the map on their copy of the global map.

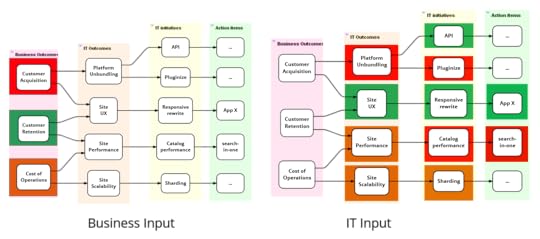

Qualitative benefits validation

Once a month (or quarter), IT and business people get together

to validate if all the IT activity has made any difference to

business outcomes. Business people come to the meeting with

red-amber-green (RAG) statues for business outcomes and IT people

may come with RAG statues for their side of the map. Both parties

need to be able to back up their RAG assessments with data and/or

real stories from the trenches (narrative evidence).

These maps can be combined

Sriram's recent book explores how best to design an IT

organization to be agile enough to survive in today's

competitive jungle.

With this the group may realize that:

Some outcomes have turned green as compared to the previous

meeting. Perhaps customer retention turned green after the last

release of the responsive rewrite initiative.

Not all IT activity is making the expected difference to

business outcomes. This provides an opportunity to discuss why

this may be the case. Perhaps because:

It is a little early in the day. Other planned items need to

complete before we can expect a difference. This is probably

why, in the map above, customer acquisition is red even though site

UX is green. Platform unbundling is still incomplete.

The initiatives and action items are sensible but a different

execution approach is needed (this is the reason in case of

“search-in-one”).

A different initiative or set of actions are required and

existing ones are better cancelled. Something outside of IT has to

fall into place before the business can realize value.

A few business outcomes are green even though the related IT

initiatives aren’t. This probably means IT matters less to this

outcome than other non-IT factors. In the map above, this is probably

why customer retention is green even though site performance

isn’t. Perhaps IT means to say that performance isn’t where it

should be although it hasn’t affected retention just yet.

To summarize, alignment maps provide a common organization-wide tool to

discuss the extent to which different IT initiatives are paying off.

They could also improve the ability to make sense of ongoing work and

bring it greater alignment with business objectives.

I haven't used this technique enough yet to claim general

effectiveness, although I do think it shows enough promise.

If you try this out I'd be glad to hear about experiences with

it.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Jim Gumbley, Kief Morris and Vinod Sankaranarayanan for their inputs.

Special thanks to Martin Fowler for his guidance with the content and help with publishing.

Further Reading

I describe other information radiators

that help the cause of organizational agility in my

book Agile IT Organization

Design . My companion web site at

. My companion web site at

www.agileorgdesign.com

contains links to further writing and my talks.

Share:

if you found this article useful, please share it. I appreciate the feedback and encouragement

August 9, 2015

photostream 88

August 5, 2015

OSCON Keynote: Making Architecture Matter

A couple of weeks ago, I gave a keynote at OSCON. They asked

me to talk about the importance of software architecture in

fourteen minutes. I put together a talk focusing on what

software architecture means and why it's important.

July 14, 2015

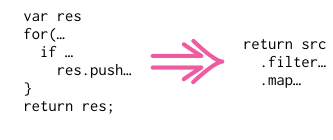

Fifth and final installment of Refactoring Loops to Collection Pipelines

In this final installment of my article on refactoring loops

to collection pipelines, I tackle a loop that's performing two

different validations on the identifiers for a person.

July 11, 2015

photostream 87

July 9, 2015

Fourth installment of Refactoring Loops to Collection Pipelines

Martin Fowler's Blog

- Martin Fowler's profile

- 1104 followers