Bliki: PresentationDomainDataLayering

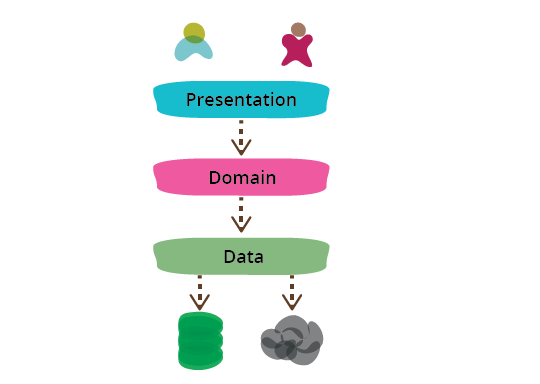

One of the most common ways to modularize an information-rich

program is to separate it into three broad layers: presentation (UI), domain logic

(aka business logic), and data access. So you often see web

applications divided into a web layer that knows about handling http

requests and rendering HTML, a business logic layer that contains

validations and calculations, and a data access layer that

sorts out how to manage persistant data in a database or remote

services.

On the whole I've found this to be an effective form of

modularization for many applications and one that I regularly use

and encourage. It's biggest advantage (for me) is that it allows me

to reduce the scope of my attention by allowing me to think about the

three topics relatively independently. When I'm working on domain

logic code I can mostly ignore the UI and treat any interaction with

data sources as an abstract set of functions that give me the data I

need and update it as I wish. When I'm working on the data access

layer I focus on the details of wrangling the data into the form

required by my interface. When I'm working on the presentation I can

focus on the UI behavior, treating any data to display or update as

magically appearing by function calls. By separating these elements

I narrow the scope of my thinking in each piece, which makes it

easier for me to follow what I need to do.

This narrowing of scope doesn't imply any sequence to programming them - I usually find I need to

iterate between the layers. I might build the data and domain layers

off my initial understanding of the UX, but when refining the UX I

need to change the domain which necessitates a change to the data

layer. But even with that kind of cross-layer iteration, I find it

easier to focus on one layer at a time as I make changes. It's

similar to the switching of thinking modes you get with

refactoring's two hats.

Another reason to modularize is to allow me to substitute

different implementations of modules. This separation

allows me to build multiple presentations on top of the same domain

logic without duplicating it. Multiple presentations could be

separate pages in a web app, having a web app plus mobile native

apps, an API for scripting purposes, or even an old fashioned

command line interface. Modularizing the data source allows me to

cope gracefully with a change in database technology, or to support

services for persistance that may change with little notice. However

I have to mention that while I often hear about data access

substitution being a driver for separating the data source layer, I

rarely hear of someone actually doing it.

Modularity also supports testability, which naturally appeals to

me as a big fan of SelfTestingCode. Module boundaries

expose seams that are good affordance for testing. UI code is

often tricky to test, so it's good to get as much logic as you can

into a domain layer which is easily tested without having to do

gymnastics to access the program through a UI [1]. Data access is often slow and awkward, so using

TestDoubles around the data layer often makes domain logic

testing much easier and responsive.

While substitutability and

testability are certainly benefits of this layering, I must stress that even

without either of these reasons I would still divide into layers

like this. The

reduced scope of attention reason is sufficient on its own.

When talking about this we can either look at it as one pattern

(presentation-domain-data) or split it into two patterns

(presentation-domain, and domain-data). Both points of view are

useful - I think of presentation-domain-data as a composite of

presentation-domain and domain-data.

I consider these layers to be a form of module, which is a

generic word I use for how we clump our software into relatively

independent pieces. Exactly how this corresponds to code depends on

the programming environment we're in. Usually the lowest level is

some form of subroutine or function. An object-oriented language

will have a notion of class that collects functions and data

structure. Most languages have some form of higher level called

packages or namespaces, which often can be formed into a hierarchy.

Modules may correspond to separately deployable units: libraries,

or services, but they don't have to.

Layering can occur at any of these levels. A small program may

just put separate functions for the layers into different files. A

larger system may have layers corresponding to namespaces with many

classes in each.

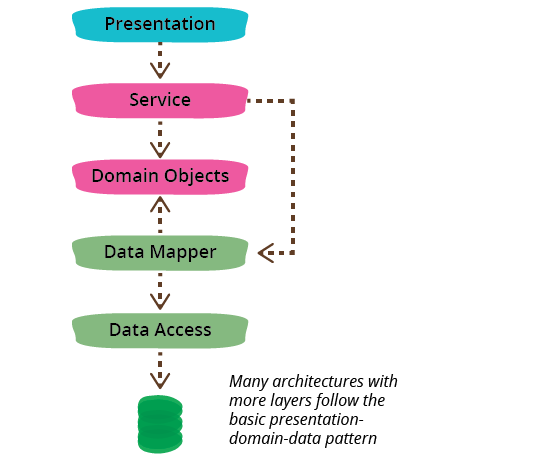

I've mentioned three layers here, but it's common to see

architectures with more than three layers. A common variation is to

put a service layer between the domain and presentation, or to

split the presentation layer into separate layers with something like

Presentation Model. I don't

find that more layers breaks the essential pattern, since the core

separations still remain.

The dependencies generally run from top to bottom through the

layer stack: presentation depends on the domain, which then depends

on the data source. A common variation is to arrange things so that

the domain does not depend on its data sources by introducing a mapper between the domain and

data source layers. This approach is often referred to as a Hexagonal

Architecture.

Although presentation-domain-data separation is a common

approach, it should only be applied at a relatively small granularity.

As an application grows, each layer can get sufficiently complex on

its own that you need to modularize further. When this happens it's

usually not best to use presentation-domain-data as the higher

level of modules. Often frameworks encourage you to have

something like view-model-data as the top level namespaces; that's

ok for smaller systems, but once any of these layers gets too big

you should split your top level into domain oriented modules which

are internally layered.

Developers don't have to be full-stack but teams should be.

One common way I've seen this layering lead organizations astray

is the AntiPattern of separating development teams by

these layers. This looks appealing because front-end and back-end

development require different frameworks (or even languages) making

it easy for developers to specialize in one or the other. Putting

those people with common skills together supports skill

sharing and allows the organization to treat the team as a provider

of a single, well-delineated type

of work. In the same way, putting all the database specialists

together fits in with the common centralization of databases and

schemas.

But the rich interplay between these layers

necessitates frequent swapping between them. This isn't too hard

when you have specialists in the same team who can casually

collaborate, but team boundaries add considerable friction, as well

as reducing an individual's motivation to develop the important cross-layer

understanding of a system.

Worse, separating the layers into teams adds distance between developers and users.

Developers don't have to be full-stack (although that is

laudable) but teams should be.

Further Reading

I've written about this separation from a number of different

angles elsewhere. This layering drives the structure of P of EAA and chapter 1 of that book talks

more about this layering. I didn't make this layering a pattern in

its own right in that book but have toyed with that territory with

Separated

Presentation and PresentationDomainSeparation.

For more on why presentation-domain-data shouldn't be the

highest level modules in a larger system, take a look at the

writing and speaking of Simon Brown. I also

agree with him that software architecture should be embedded in

code.

I had a fascinating

discussion with my colleague Badri Janakiraman about the

nature of hexagonal architectures. The context was mostly around

applications using Ruby on Rails, but much of the thinking applies

to other cases when you may be considering this approach.

Acknowledgements

James Lewis, Jeroen Soeters, Marcos Brizeno, Rouan Wilsenach, and

Sean Newham

discussed drafts of this post with me.

Notes

1:

A PageObject is also an important tool to help

testing around UIs.

Share:

if you found this article useful, please share it. I appreciate the feedback and encouragement

Martin Fowler's Blog

- Martin Fowler's profile

- 1104 followers