Abigail Ted's Blog, page 2

June 5, 2023

Understanding Mr Vincent’s ethnic ambiguity in, Belinda (1801). Race and Regency#4

Mr Vincent. A wealthy, charming, popular and good-natured gentleman with emotional depth, and believable and significant flaws. Vincent is described in the first edition of Maria Edgeworth’s 1801 novel, Belinda, thus:

‘ Mr. Vincent was a creole ; he was about two-and-twenty: his person and manners were striking and engaging; he was tall, and remarkably handsome; he had large dark eyes, an aquiline nose, fine hair, and a manly sunburnt complexion; his countenance was open and friendly, and when he spoke upon any interesting subject, it lighted up, and became full of fire and animation.’

Maria Edgeworth (1768–1849) in an 1841 photograph.

Maria Edgeworth (1768–1849) in an 1841 photograph.In writings from the Regency Era, the term ‘creole’ is rather ambiguous. At a surface level, it refers to a person native to the West Indies —any child, of any race, born and raised in the West Indies. Creole persons born to Black parents were often distinguished as ‘African Creole’ or ‘Afric Creole.’ The singular term ‘creole’ is less clear in its meaning.

Academics are not in agreement about how to approach characters described as ‘creole’ in literature of this period. While some contradict suggestions that the term necessitated non-whiteness, most appear to concede that the descriptor was intended to elicit doubt about an individual’s claim to ‘racial purity’.

Edgeworth describes Mr Vincent’s features as being stereotypically English, with the exception of his dark eyes and sunburnt (tanned) complexion.

Knowing the implied racial ambiguity that accompanied his designation as ‘a creole’ Edgeworth’s choice to add features to Mr Vincent that emphasise rather than quash such questions in the mind of her readers is significant.

Many interpretations of Mr Vincent, and Edgeworth’s decision to make shocking revelations about his character that lean heavily into common 19th-century negative stereotypes about Black Africans, understand and analyse him as a romantic figure of both White and Black heritage.

Belinda does have an acknowledged and unambiguously Black character, Vincent’s servant, Juba. While much of Juba’s appearance in the novel appears to be for comedic effect, he has a mini-plot of his own, ending up, in the first edition, marrying a White English girl.

This mini plot was removed in subsequent editions of the novel, with Edgeworth explaining this decision in 1810:

‘My father says that gentlemen have horrors upon this subject, and would draw conclusions very unfavourable to a female writer who appeared to recommend such unions.’

Later editions of the novel also saw changes to Mr Vincent’s role as Belinda’s secondary love interest, with moments of romantic tension being reduced and a proposal scene entirely removed.

This convinces me that Edgeworth intended Vincent’s character to be of both White and Black heritage. Having made a point of adding an interracial marriage mini-plot to the story, it seemed unlikely that subtle hints of Mr Vincent’s mixed heritage were accidental.

That Edgeworth would return to the text and remove romantic tension between Belinda and Mr Vincent after being chastised for including interracial love in her novel seems to suggest two things:

Mr Vincent’s character was viewed by Edgeworth and her readers as being of mixed ethnicity. Why else would she remove and change scenes that increased tension and suspense in the story?Black and mixed ethnicity characters were considered as acceptable characters within Regency Era fiction, but not as viable love interests for White women. You’ll remember from previous blog posts about the particularly sour feelings towards interracial relationships amongst even ‘liberal’ Regency Era folk. Edgeworth’s father was possibly trying to avoid associated implications that his daughter was sexually licentious — a common accusation directed at White women who held romantic affections for Black men.I hope you’ve enjoyed this exploration of Mr Vincent’s racial ambiguity. We’re not done yet with Edgeworth’s, Belinda. An analysis of Juba’s portrayal, and the novel’s use of common stereotypes associated with Black and Jewish characters will come in later episodes of ‘Race and Regency.’

Adieu for now! :-)

[image error]June 1, 2023

You’re a Doll, Daisy! Chapter Three — The Appearance of a Carpet Burn.

Tom was now sleeping, recovering, we must suppose. With what admirable chivalry had the dear sportsman excused his step-lover — as we might call her — any wearisome exertion in the time since we took our leave of their private interview. Daisy did so say that she loved a romantic man. The lady had been watching him sleep for a short while and presently took up her pen to resume the narrative she so diligently related to her brother Dapper:

‘I own that in my letters to you I have exhausted the subject of any interesting things past and find no pleasure in guessing at my future; so, the present shall have to suffice. Dear Tom — there is a display of the most frightful twitching and grimacing upon his face; he must be, I think, in the grips of some dream-state terror. Seeing it just now caused me to think of Freddy. How he did once suffer in that way. I wonder if still he does. He would not tell me, nor anybody, I suppose. He would say, “Where is the fashion in fear?” I think you were never so concerned with the threat of unmanning yourself at his age or at any age, my dear.’

‘If it never should require sharing him, I would recommend a Tom Finsbury to every woman in the world. I know I need not evangelise you. Forgive me, this is becoming very tiresome to write; I can have nothing else interesting to tell you at present; I shall leave off here for a while–’

‘I am returned and what a carry-on is performed before me now! All for a little carpet burn. To tell the absolute truth, I took my leave of this letter earlier because I had been clobbered by a gust of inclement and ill-timed passion. Looking at the felled Goliath reclined on my bed, I would have slung my shot at him a second time and I employed a coughing fit for the purpose of waking him, planning to present my proposition thereafter. “Odd’s life, Daisy! Is that really the time?” said he, before I could say a word myself. “Sure as a gun, we shall be late for supper! Gad… why did not you wake me sooner? I’m damned hungry! What!” And he began to slip back into his shirt like a ferret.’

‘To this, I exclaimed a very charming, “O — fie! Hang supper! How ungenerous to starve a girl in this way!” He laughed because I did. I am sure I meant to say it quite seriously. “Was ever a poor woman’s heart broken, by such a handsome tormentor, as mine? What a tedious relief are the mere moments we can steal away together!” Still, my dratted smile would persist though I had wanted to cry; thus, he smiled his reply also. “I must get dressed, Daisy. It really is quite chilly in here. And once my father is asleep, we’ll have the entire night.” I tried to make a face like I would cry, for I really felt like it. Tom saw my twitching face and professed with his generous West End swagger, “By Gad, don’t be brought to tears, Daisy. I’m quite aflame with desire and all that, but I am terribly hungry. I really am flagging so severely, I could barely hold a sparrow against the wall!”

‘Standing myself upon the bed, I clasped his beautiful, moustached face between my fingers and sighed, “Oh, Tom! My dear heart! Sure, we have still a few moments to spare, and I am in no want of power to please–” Regretfully interrupting this profession of my sincerest affection was a rapid succession of knocks at the door. I have noted to you before of Mrs Prudence’s habit of knocking while already entering my room, only though when Tom is in my bedroom; I do not doubt for a minute her virtues; sure, she means to terrify us towards redemption.’

‘Dear Tom’s modesty was precariously preserved by the great length of his shirt, and as he began reaching for his breeches, she scorned us both by saying, “Sure, Mr Finsbury, you need not fumble about with that embarrassed look upon your face; there is nothing of your person that could bring a blush to my cheeks. Though to be sure, I am surprised you, my lady, can hold such a serene face when caught with your hands sinful red. But then, I have always thought boldfaced whores wouldn’t know shame if it looked them in the eye — if you’ll forgive my saying so.” A charming little lecture. Indeed, my dear, give me a Mrs Prudence over a sycophantic slitherer any day!’

‘I asked the dear woman what had caused her to come into my room. “Content yourself, my lady, sure I did not break in upon you here so that I might be witness to your unnatural vices,” began she. “Vile slut and witch that you are, I can only but wonder what reasons you entertain for my breaking in with such little warning, not knowing what debauchery might greet my poor eyes. Sure, no servant is put upon as I am!” This, as you have seen, did not answer my question, which I repeated to her.’

“Sure, I came to warn you that Sir Charles is awake and making his way up the stairs.” How my Tom leapt across the room. There is no dark-closet in this apartment, and no amount of will could confine his great figure to the little wardrobe. Genius man, he would not be outwitted by this inconveniently designed room, and flung himself into an elbow chair and had me and Mrs Prudence heap upon him as many gowns, petticoats, shawls, and stockings as we could find.’

‘A moment later, burst through the door my husband. Before this, taking a pinch of cunning from my love, I had grabbed my chamber pot to have in view of the man as he entered. Mrs Prudence played her part exemplarily, “Pho, sir! It is a custom upheld by all gentlemen of good breeding to knock before entering the bed-chamber of his wife. Marry forbid you should have burst in upon us a moment later! Do you not see what your wife holds in her hand?” What a response this brought forth! — I really wish you had been here to hear it all, but I shall attempt — I hope not in vain — to convey things as they happened.’

‘Sir Charles was quick to revile her. “Female servants,” said he, “were so adept to growing pert with age that he would have the law prescribe every Rebecca, Fanny and Betsy thrown penniless to the street for a year’s humbling the day they turned thirty.” If the woman did not keep watch of her tongue, he would, as a Magistrate, find some way of conveying her tongue and her to be made an example of at Newgate! The wit finished with a phrase in Latin; I knew not what it meant. I shall ask Tom by and by. You once told me that only stupid men use words they hope others cannot understand, or perhaps that was George.’

‘I am so long accustomed to laughing at every joust the man makes; I do not know whether I laugh at his absurdity or mine anymore! “Fie, sir!” I fawned sweetly. “Fie?” replied he. “Did she say, fie, Mrs Prudence? Or was the word pie? Yes. Pie, sir! I am sure that is what the girl said. Pot-bellied little wench she is becoming!” He is really quite furious with me for every mouthful I eat lately. Imagine his fury when he will discover this belly is not all grains but grandchild!’

‘Tom, you know, who will bear every offence against himself, cannot even pretend to laugh at those flung my way, especially those by his father. I have tried a hundred times to tell him not to allow his blood to rise against these absurd jests — for that is all they are. Why enrage yourself with the follies of others when you could be laughing? Resentment rarely performs any great service to those who will hold it in their possession.’

‘But a hot head needs must be a romantic one, and I cannot help but love a romantic man, nor a man so wholly unpragmatic. Tom is a man carved from unbridled and untameable passion — I would not really change him for a world of riches. However, at that instant, I was forced to repress his spirit a little, for I saw he would stand up from the chair and challenge his father. Before the old justice noticed the motions of my gowns, I threw myself in a fit upon the elbow chair in which Tom sat.’

‘As I ran to the chair, it was not my hidden love who was discovered, but something upon my person I had yet no notion of. “Her back, Mrs Prudence! What is that mark on the little woman’s back?” He would have made me turn around. I insisted I was overcome with a fit of unrelenting dizziness and must be left to rest in my chair; I could feel my love raging beneath me. “Damn me, if I care for your fits! Get off that chair, woman!” roared Sir Charles. “No, I shall not, sir,” I replied, attempting to affect that pleasing face I mentioned to you a while ago. I did not know then what mark I was hiding upon my back, but in any case, I wanted to prevent Tom’s getting up.’

‘We went back and forth in much this way till Mrs Prudence chose her side. She has more opportunity to see the colour of his money than mine, I suppose. “Pho! Sir, will you allow your wife to disobey you so boldly? Sure, it is not my place to tell a husband how to hold the law in his own home. But I would warn my lady that I have seen women receive a hard belting for saying things far less provoking.” This did not though work upon my husband in the woman’s favour; he promised her much violence if she would threaten “his little woman” again.’

‘I have never once witnessed either able to withdraw honourably from a bullying game, and the two have now been exchanging the most amusing incivilities for quite some time. So, here I remain upon good Tom’s lap. You will see my hand has entirely wobbled across the page!’

‘You must notice I write in the present tense — I am well practised at making short work of writing, and there was pen and paper within reaching distance of this darling elbow chair. Delightfully, as every word intended for my husband’s ears must be shouted — and shout Mrs Prudence does — Tom and I have been at liberty to carry on our own conversation in the corner here.’

‘Making a little space for his eyes, I asked my love to spy for me what it was upon my back that had caused all this calamity. A carpet burn, Brother! Sure I heard a crack of tears break into Tom’s voice, “Good God, Daisy!” I heard him whisper. “Oh, what a cruelty it is to materially wound the woman you love. I cannot even look again at your back, Daisy. Damn me! Damn me, Daisy, and my rheumatic knees!” How this caused my heart to bleed! “Oh, my love,” said I softly, fumbling a little hand to grasp one of his gargantuan arms. I could have wept just then for loving him so.’

‘I want so desperately to tell him. Sure, the child is his. Save for some demonic intervention, it could only be his child. But yet, once he knows — Oh, once he knows! I think he may not be able to keep the happy secret as well as I have. You are the only person I have told. I hope this child will be an exact miniature of their perfect father. If even a fingernail is not the same, how disappointed shall I be! You must see my thoughts have shortened. I really am very hungry.’

[image error]May 26, 2023

You’re a Doll, Daisy! Chapter Two — In Which Tom Curses His Stomach.

A talent for penning the details of their own narrative, even amongst the most unobliging of circumstances, is, I am sure the reader will concur, a most becoming quality in a heroine. Rather conveniently, our own heroine was an accomplished penstress; Daisy kept a skilful narrative of all that happened to her. I say conveniently because it shall burden much of the storytelling in this tale.

If we are to be punctilious, it ought to be said that this perpetual narrative was not a diary — as the reader might have hitherto been encouraged to believe — but a series of letters to one of her two brothers, though he never now replied to her.

The name of this brother was Mr Dapper Lyons. Dapper he was, and Dapper really was his name. His father, when a young lieutenant whose lady was expecting to soon deliver him a child, having been left one evening without anything of value with which he could wager, had put forward the naming rights for his firstborn to secure a wager; a wager he, one half-hour later, lost. Much like the gamester who designed his name, Dapper had been something of a polymath whose often-expressionless face was well formed for disguising his genius in any matter.

At five years her senior, and distinguished by his father as the beneficiary of an education rarely bestowed on the sons of whores, Dapper had been Daisy’s first and favourite tutor in life. He had taught her to read and write and asked always for her letters, and, though he had ever been little inclined to reply, Daisy could never forget to write to him, not a single day that she had access to pen and paper. Below sits some pages of a letter from Daisy to her brother Dapper for the perusal of the reader:

‘Today, I received the sweetest letter from dear Freddy. He has, I fear, your mischievous character; I learn he creates much outlandish speculation amongst his peers as to who exactly pays for his education. He has half the school convinced his father had died famously at Waterloo and left the poor orphan with ten thousand a year, others that he is the lovechild of a Lord Something and a French actress, his schoolmasters that he is an MP’s natural son — or a stock broker’s hidden child — sometimes heir to a business empire in The North.’

‘I think there is a natural roguery in all clever young men; how boring must school be for those boys to whom learning comes so easily. You were much the same if I remember rightly. I have copied the lines of his short epistle; he mirrors you also in his lack of replies, but then I suppose you are long dead, my dear, so you have a much better excuse! To his credit, I will own to you that his handwriting is far neater than your big, loopy letters ever were. Here was the contents of his note:

“Capital bottles of wine Tom sent over. Send him my thanks and that sort of thing. Swell trick hiding them in that case of books, Yates didn’t suspect a thing — we all had a dammy good laugh about it. You know I hate to be a hound, Dais, but I was utterly cleared out when I went to stay with Harlow’s lot — 20£ doesn’t last long a week in Town, and McMillan has called me up on the five I owe him.”

There! I found the letter once we returned to our lodgings here in Camden Place. I read it over again and again — five times — before clutching the dear object to my heart — just where once I held him when he was an infant. Oh, what a perfect, tiny creature he was when he was born and now what a swaggering little gentleman he has become!’

‘Of course, I can do nothing without the eyes of Mrs Prudence upon me. “Marry forbid!” she ejaculated, quite breaking me from the charm of dear Freddy’s letter. “Why, sure that is your brother writing to plead the case for his empty pockets again?” I wish she would not be so severe upon him; he does not at all deserve such treatment. He is only seventeen and works very hard at school. He ought to have a small income at his disposal when he goes to London. You always did. And why should not he engage in the follies of every other clever young man? There is money aplenty to be had. If there is one habit of character I cannot attribute to my husband, it would be his being a miser.’

‘Indeed, yesterday, when we were out walking and the rain came on all of a sudden, Sir Charles paid some dishevelled-looking girl the entire contents of his coin purse to take her very shabby-looking umbrella. He had intentionally built my expectations upon the umbrella being for my sake but held it all the while quite away from me — my husband was monstrously diverted by his own trick. It was a fine trick, to be sure; I laughed a great deal and more so when we arrived amongst the crowds at the pump-room and he had me look at my awful appearance in a mirror. It was a fine trick, indeed, it must have been, for so many people seemed to find amusement in it — I had to laugh, my dear, I could not help it!’

‘Mrs Prudence really is a delightfully earnest creature and would not be distracted, disarmed or dissuaded by my diverting tale. “Oh, but does not her ladyship consider the dangers of giving a young man at a public school such ready access to money all the time? You give him all the latest fashions, a gold watch and chain, only ever new books, a haircut every six weeks in Town, and pockets full of money to spend on all manner of vices — Oh, should every young bastard have you as a sister we would be a nation of reprobates and depraved sensualists!” Though I truly esteem her moral niceties, I warned her not to reflect too severely upon young men at the public schools.’

‘It was at this moment, before Mrs Prudence could reply, that my dear Tom entered the room. “What ho, Pru! How do?” The dear woman — I really do adore her incessant mothering — could hardly keep a short lecture from her tongue.’

“Would to Heaven, Mr Finsbury, sir, you would not come barging into her ladyship’s apartment in such a way. Anybody might have been in here, your father even — then what should you have said for yourself, sir!’ Before my sweet giant could give a word of reply, she flung to an ever more fervent raving. “My detestation for vice and its lovers,” said she, throwing her hands and eyes to high Heaven, “would have me send you from this room immediately, Mr Finsbury. And if you knew what was good for you, sir, you would take yourself out. Tis’ a vile and unnatural bewitchment between the two of you. How quickly you wrap your winding, serpent arms about one another’s doomed necks, engaging in a thousand poisonous encounters. Each bitter one shovelling another heap of fuel upon the flames in which you shall hereafter burn! But, tis’ not the place of we servants to moralise our masters. God shall judge ye both well enough.”

‘Good woman! I am sure she shall save my soul yet. But not this afternoon. Tom, having quite ignored her expostulations, was sat with his shoes up on the bed. There was a sort of silent lull between us all, and so I asked Prudence if she had run me a bath. She answered to say that she had and went grumbling from the room, cursing us both to the wrath of the Devil as she went. A most amusing pun entered my head — though after I said it, I thought, “Perhaps it is not a pun.” I asked Tom, but he seemed not to know either. You, Brother, would know, I am sure.’

‘Anyway, I said to Tom, “How would you like to take a bath with me in Bath, Tom Finsbury?” I am not sure he quite appreciated my witty little wordplay, but he clapped his ginormous, soft hands together and exclaimed, “Hang me if I ever offer a negative to that question, Daisy!” I felt my heart quite double in size; I really cannot help but love a romantic man.’

‘Shortly, my moustached love leapt from his seat. “Oh, but hang it, Daisy, all that coffee I had downstairs has left me with a wretched bad stomach. And I am certain there was something a little putrid in the quail I had at breakfast. No… hang my weak stomach, but you should not share bathwater with me, not today.” I was, of course, very disappointed, but I am always of the maxim carpe secundum when presented with an opportunity of a private interview with my straw-lipped dandy.’

‘The ingenious little creature that I am, I quickly overcame the obstacle that bad fortune had so cruelly placed in my way. “Then I shall take that chair,” said I, “and set it down by the bath so that you might watch me.” A fit of passion hit my lover — I could see from his face — like a clap of thunder. “Gad, really?!” exclaimed he. “By God, Daisy, you drive me damn wild… damn wild like a… like a damned…” — Oh dear, it seems I am obliged to break off — It is not necessary to remind you how much I am,

Your most affectionate and loving sister,

Daisy.’

We are obliged to remove from Daisy’s letter here and return to our usual mode of narration. A very audible gargle of Tom’s stomach finished that above sentence for him, and so poor Daisy was left to take her bath alone.

Dear Tom, whose circumstances it is perhaps best if I avoid relating, was always utterly astounded that a woman like Daisy, incomprehensibly pretty and fine-figured as she was, could think to even look at a man such as himself, let alone gaze adoringly at him from her bathwater. As he underwent the bodily experience which has rightly been deemed indescribable, our charmer thought to himself what a lucky fool he was.

Daisy, rather less precariously disposed, was entertaining similar reflections of her own fortune; after many years of their steady attachment, her beau regarded her with the same pure wonder and amazement as he had done when he was a stammering, blundering, forever-blushing young chap.

While Mrs Prudence stood on the landing keeping guard for the prying eyes or ears of gossiping lower servants, our happy fellow, his trial being over, returned to darling Daisy’s apartment, where sat she already in the bath. How could not she smile to be sitting across from the sweetest and dearest yellow-moustached face in the world, saying little else but, ‘Gad, Daisy… hang it, you are just… you are just damned perfection… do you know that… of course you do… by God, Daisy…’

[image error]May 21, 2023

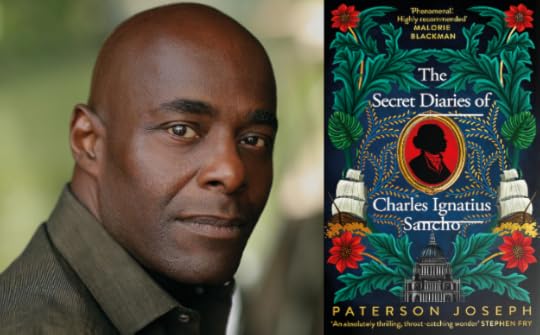

‘The Secret Diaries of Charles Ignatius Sancho’ by Paterson Joseph — A book review.

What do I have to say about Paterson Joseph’s novel, The Secret Diaries of Charles Ignatius Sancho? A lot. Can I neatly and coherently articulate those things in a single blog post? Probably not, but I’m nothing if not a trier in life.

Firstly, for those yet to read the novel, a word on which format might suit your tastes. From my reader friends who are fans of audiobooks, I have had countless recommendations for the audiobook version of this novel.

Having now seen Joseph read excerpts of his book on stage, it is clear to me why.

A well-performed audiobook of a great novel produces an immersive reading experience like no other. I do not doubt that’s exactly what you’ll find with this one — the perfect format for readers wishing to intensely feel this story, and a great story it is. I shall be adding this to my audiobook tbr for a future ‘reread.’

Some matters, though, can be lost in translation when it comes to audiobooks, and to best appreciate narrative structuring, framing, symmetry or asymmetry, stylistic flourishes, prose style, diction, syntax etc., (if that’s your thing) I prefer to see the words on the page for myself.

For those who, consciously or unconsciously, derive personal satisfaction from the craftsmanship of good novels, this book will deliver.

This directs me towards the two things I’d like to focus upon for my review, the story or plot (which, in this context, we shall use interchangeably) and the craftsmanship of the novel.

Beginning then with the story. The Secret Diaries of Charles Ignatius Sancho, is a fictionalised narrative of a real story, the story of Ignatius Sancho — wit, reader, gentleman of letters, composer, husband, father, shop owner, and (we think) the first Black Briton to vote in an election.

Sancho was also born on a slave ship and shortly thereafter sent to spend his childhood as a sort of plaything/companion/servant for three sisters in Greenwich.

This remarkable life is the story Joseph retells in his fictionalised diaries and, for those who have read about the history of Sancho’s life and read Sancho’s own letters, Joseph remains close to the truth at all times.

For Joseph, his interest in Sancho’s story has been a deeply personal and decades-long obsession.

This, his debut novel, is far from his first venture into sharing Sancho’s story and it is doubtless that this longstanding closeness to a man who died almost 250 years ago has enabled Joseph to produce such an authentic and engaging character portrayal in his novel.

The story of this novel, the focal figure of this character-driven tale is that of the real Sancho — Joseph has taken an incomplete sketch and returned us a clearer, more vibrant image.

So, is that it, Joseph has produced a well-written, accurate and engaging work of historical fiction based on the life of Sancho? — I mean, yes, he has done that and if you appreciate good, close-to-truth historical fiction about interesting people, that is exactly what you’ll be getting from this book.

But I do think there’s more to this book than that and, for me, this is spoken through the framing of the narrative and the presence of ‘the implied author.’

Here we move into discussing the craftsmanship of the novel. To begin, Joseph frames Sancho’s story within his (Joseph’s) experience of Sancho.

Joseph begins and ends the novel with a dated address to the reader, starting his dialogue in September 2021 and ending it in June 2022. Joseph is a character in Sancho’s continued history and is, to some extent, a character in the novel also.

The ‘implied author’ — that is, an impression of Joseph that is left on the pages and between the lines of this novel, is remarkably clear. We must not confuse the narrator with the storyteller here. Sancho, or Joseph’s reincarnation of Sancho, is the primary narrator — telling his own tale in a first-person dialogue of diary entries, letters and writings to his son.

When a storyteller (in this case, Joseph) leaves a distinct impression of themselves throughout their text, in choices of style, diction, structure etc., and the themes and questions they leave imprinted on the story, they become a character in their own right; this is our ‘implied author’ and Joseph is implied in almost every line of this novel.

His choice to embrace a more complex and elegant prose style, his use of Dickensian-inspired descriptions, his choice to situate the story within a dialogue from father to son, his choice to close doors and drop hints and simply refuse to fill many of the blanks in Sancho’s story — all this characterises the storyteller.

Of course, the ‘implied author’ may have no likeness at all to the real human who wrote the book. Yet, in this case, I rather get the impression that, much like Sancho, the storyteller we meet in this novel is an authentic portrayal of the real man.

A final word on craftsmanship, and back to framing again. Anne, Sancho’s wife, narrates for no insignificant portion of this tale through her letters. This adds a third dimension of framing.

Initially, we are met with Sancho’s story, then Sancho’s story as it relates to Joseph’s experience of knowing Sancho, and finally, Sancho’s story as distilled within a moment of complex, sprawling, multidimensional British history: Black Britons during the age of British slavery.

Anne offers a glimpse at the dark and unpleasant world beyond Sancho’s narrow experience of slavery and the two worlds contrast significantly. Anne’s perspective broadens Sancho’s tale and enables the reader to place his individual experience within the wider narrative of the Black experience during Britain’s slave trade.

I could go on, but I won’t. I shall end things here by saying, a five-star read for me, that I’d recommend to all readers.

[image error]May 18, 2023

You’re a Doll, Daisy! Chapter One — Beginning Our Tale with a Family Affair.

Chapter One

Chapter OneBeginning Our Tale with a Family Affair.

Before we begin, it must be said that this tale does not take place in a world that shall be found between the pages of an Austen novel. That is to say, our characters, decked in flowing nylon gowns and plastic jewels, inhabit the world of a 1965 Regency drama.

I am conscious that the large false eyelashes and beige lipstick have oftentimes been somewhat distracting to onlookers but I am not at liberty to alter the world in which our story takes place, and I hope you shall not think any less of our heroine if a little mascara cascades down her cheeks every time she weeps. Weep she shall aplenty; misery seemed apt to follow this pretty creature throughout every walk of her life.

I shall not suppose to ask my reader to like the characters you shall shortly hereafter meet — sure, I did not always like them very much myself. Many of our players are quite worthy of being despised. Lastly, I shall say, the archaisms of style, language and spellings employed in this tale were chosen for no better reason than my liking them. And with no further delay, I invite you to imagine the most beautiful, doll-featured girl in the world, for that is our heroine.

This young woman was determined to be unconquerably and invincibly affable; every word said to her was delightful or clever, or at the very least, diverting. There was no insult she could not suffer with remarkably good humour and the motions of a frown were entirely unknown to her face. Perhaps that is why, at the age of thirty, our heroine had still the prettiest face in England.

In the assembly rooms at Bath, Tom Finsbury sat beside this young woman — to whom his entire soul and heart were fastened — and his aged father, who was married to her. She was, though not five months separated their days of birth, Tom’s stepmother. Save for rebuking or instructing, Sir Charles was little inclined to speak to his wife and had long ago prevented the lady from forming any friendships, such was his jealous rage at the prospect.

Tom was ugly, stupid and unmarriageable and Daisy’s fondness for him could only be a mark of her good humour. He was a fool and a natural jester and as such, Tom’s friendship with his stepmother was quite tolerated. So unlovable did Tom appear in the eyes of his father that Sir Charles remained entirely oblivious to the effect this stammering blockhead had upon his wife’s heart.

By a happy accident of old age and infirmity, Sir Charles was so close to the precipice of total deafness that he could not hear a single thing unless it was bellowed to him.

‘I should like to take a bath when we return home,’ said the young lady in a low voice to Tom without offering him a glimpse of her eyes. Tom smiled but would not reply. A great many eyes rested upon this family party. Tom naturally attributed this to the large port-wine stain under which the left side of his face was blanketed; a part of his features that, to his lover, made the sum of his pretty face only more perfect. Daisy, with greater accuracy, attributed the lingering eyes to a shouted conversation Sir Charles was having with his neighbour.

‘Congratulate me, Mrs Davies? This porcine creature here,’ he said, somehow raising his voice further and jabbing Daisy in her middle, ‘carries the weight of nothing but her own idleness and overindulgence.’ Daisy offered Mrs Davies the most beautiful and charming little laugh. Sir Charles, plagued that last year by a particular branch of infirmity, could have had no reason but a suspicion of cuckoldry to believe his wife might be big with child and not cake.

Tom had many reasons, or perhaps we should say, memories, from which he ought to have at least suspected that Daisy’s sudden expansion since their arriving in Bath was not only by cause of the rich meals. And had this gallant young hero thought anything of Daisy’s ever-plumpening neckline except that it was very pleasing for him to behold, he might have wished to appear a jot less offended on Daisy’s behalf.

Upon hearing the offence, our gallant hero was incensed; the face behind his glorious straw moustache was quickly overrun with a crimson rage. ‘Damn your eyes, sir!’ As Tom rose to his feet, he knocked over a wine glass, and his chair clattered to the floor. ‘My stepmother is an angel, a damned angel. Hang it, sir, hang you, sir, you confounded wretch, I will not allow you to speak to your wife in that way!’

If you looked hard enough, you might have seen his armour sparkling in the candlelight; Daisy did. Sir Charles was not angry at his son’s preposterous display of attachment to Daisy, rather, he was very much amused by it. Tom had such a talent for being ridiculous and without ever trying. In fact, the morning Sir Charles and Daisy were wed, Tom had leapt from his seat, shouting, ‘Faith, Daisy! You cannot, you cannot marry this old tyrant. Good God! You are the thread with which my heart is hemmed; you are in every stitch of my soul!’ All, of course, to no effect except laughter from his father.

Returning to the assembly rooms, among the sounds of Sir Charles’ booming laugh, Tom began to shout, ‘Hang it, man, someone fetch me a gun! I do not care how old you are. We shall settle this like men!’ He was overcome with such a Herculean countenance, such a musk of manliness, that — had it not been for their being together in a busy public room — Daisy would have climbed dear, sweet Tom like a fig tree!

[image error]April 18, 2023

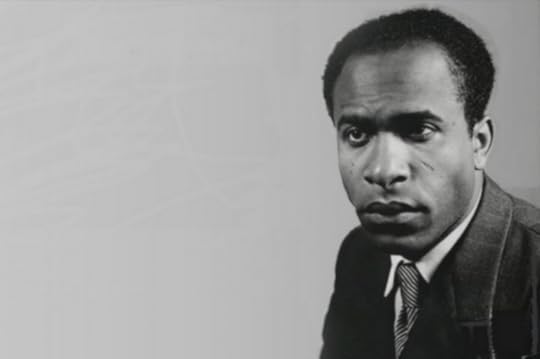

‘Black Skin, White Masks’ by Frantz Fanon. A Book Review.

When I went book shopping for my 30th birthday in February 2023, I had never heard of Martinican psychiatrist Frantz Fanon, nor his ground-breaking work ‘Black Skin, White Masks’ which was originally published in 1952.

This was an impulse purchase based entirely on my intrigue at the cover (which features the above portrait of Fanon) and the title of the book; the back cover offered very little in the way of describing what was waiting on the pages within.

When I sat down to read it some weeks later, I was still as intrigued and as clueless as the moment I decided to add this to my ever-burgeoning pile of books to take to the till.

I have rarely come across a text that manages to so seamlessly knit together rational, objective argument and a personal, emotional narrative. In BSWM, Fanon explores the psychological confusion that is present in the mind of ‘the colonised.’ A relevant and important topic even to this day (rather, especially in this day).

And Fanon’s use of language and the powerful, immediate tone of his prose feels exceptionally modern. Fanon explains to his reader microaggressions and the importance of lived experience, and many other concepts that have only recently found understanding amongst the wider population in the West.

The racism experienced by Black people (he specifically writes about the experience of young Black men) living in the shadow of colonialism in majority Black populated countries, or living in majority White population colonising countries, Fanon says, creates a confused self-understanding and self-hatred that wields the power to entirely fracture one’s identity.

Not only does Fanon elegantly and persuasively lay out a pragmatic argument for this theory, but he allows his academic voice to slip into glimpses of unmasked internal fury and confusion — taking the reader along for the ride through bursting stream-of-consciousness moments. Fanon offers up his own thoughts to produce an example of the ‘neurosis’ he’s discussing.

I cannot do justice to this text by attempting to unpack the more specific themes and experiences explored within; perhaps that explains to me why the back cover was so vague. Some books, I think, you just have to read without quite understanding what’s inside beforehand.

This is not a light read. It gives an in-depth, and two-pronged exploration of the mental weight of waking up every day to the drip, drip drip of persistent racism. Five stars from me, and I would wholly recommend it to everyone, but particularly those interested in Black scholarship and the social history of colonialism.

[image error]March 13, 2023

Clarissa Read-Along (Letters Dated 6th-12th March)

‘Things Can Only Get Better’ as D:Ream once famously said, unless you’re Clarissa in Samuel Richardson’s classic tragedy of the same name, in which case, things will just keep getting worse.

It’s been a harrowing week for our heroine, with lots of letter writing between the Harlowes and our favourite side character, Miss Anna Howe.

In our last group of letters, it was becoming increasingly obvious where Richardson was hammering in moral lessons intended for the reader (one might even suggest too bluntly). It seems everyone but Clarissa herself is straying from the path of proper virtue (yes, even our beloved Anna). This week was no different, with our main lady and her good friend continuing to examine the behaviour of Clarissa’s tyrannical family in that logical and considered way that seems so alien to the high tones of emotion vibrating throughout the rest of the story.

The more Clarissa resists, the tighter the hold about her becomes; with her maid Hannah now fired and her time beyond her bedroom much restricted, our young lady is forced into increasingly clandestine means of finding support for herself. Therein lies the main message within this group of letters. Clarissa states it repeatedly: if her family are so determined they do not want her to marry Mr Lovelace, their behaviour is forcing her towards that very fate.

Beware, parents who wish to control the hearts of their young daughters, one cannot tyrannise a daughter’s heart into obedience in such a delicate matter as marriage.

Mr Lovelace is starting to find his footing in the novel, as his name crops up again and again. Anna has been doing some digging, and still seems convinced that this rakish fellow is her friend’s best hope of escaping the awful Mr Solmes.

All we knew about Mr Lovelace for much of the novel until now had been deduced from various reports and gossip. With Mr Lovelace appearing at church, seemingly to seek out Clarissa in person, one begins to wonder just how bold this fellow might become.

‘This man, this Lovelace, gives me great uneasiness. He is extremely bold and rash. He was this afternoon at our church — in hopes to see me, I suppose: and yet, if he had such hopes, his usual intelligence must have failed him.’

Hints are beginning to appear that Lovelace has some insight into the inner workings of the Harlowe household, which is putting Clarissa on edge. She describes her communication with him as something she feels most uneasy and unhappy about doing. She finds Lovelace very ready to be pleased with the slightest hint of approbation from her side. With encouragement so quickly found, we begin to feel how carefully a Georgian young lady must play her cards.

The threat of the impending marriage to Mr Solmes continues to close in upon our young lady, it begins to feel as if there is nobody in her own family who might put an end to this misery. Is Mr Lovelace the answer? Anna would say so, yet Clarissa is far more measured in her judgement of him; he is a notorious rake. But then young women imprisoned by their own cruel families can’t really be choosers.

‘O how you run out in favour of the wretch! — His birth, his education, his person, his understanding, his manners, his airs, his fortune.’

It seems that Bella is quite convinced of her sister’s infatuation, but Clarissa herself admits to only a ‘conditional liking’ — meaning, reduced to a circumstance of choosing between him and Mr Solmes, Clarissa can find enough to like about Mr Lovelace to make him a tolerable prospect. But will she really be forced into such a choice?

The wait is almost over, just around the corner we have letters from the primary gentleman of this story, Lovelace. It is then we might pick away at the layers of his character for ourselves.

Until next time, adieu, my dears!

[image error]March 10, 2023

Lord Byron’s Enslaved Black Groom. Race and Regency #3

When prolific seducer, useless husband and deadbeat dad, Lord Byron, died in 1824, his friend William Parry gushed praise for the late poet onto the page just a year later, publishing, ‘The Last Days of Lord Byron’ in 1825. The intended effect, presumably, was to respect his lost friend with a book showing how funny and clever Lord B was. IDK. Honestly, ‘The Last Days’ makes Byron seem like the most insufferable human being who ever lived.

But we’re not here to discuss Byron’s general arseholery. Today, we shall be looking at what Parry’s book tells us about race and racism in the Regency Era through a vignette of Lord Byron’s Black groom:

‘Lord Byron had a black groom with him in Greece, an American by birth, to whom he was very partial (this man died in London a short time back). He always insisted on this man’s calling him Massa , whenever he spoke to him. On one occasion, the groom met with two women of his own complexion, who had been slaves to the Turks and liberated, but had been left almost to starve when the Greeks had risen on their tyrants.’

Almost immediately we’re met with a glimpse at what sort of treatment this groom experienced from Byron.

‘He always insisted on this man’s calling him Massa,’

The term ‘Massa’ is often found in British texts of the long-eighteenth century, representing how enslaved people in the British West Indies would say ‘master.’ Often creole or mock creole was exaggerated and used to sketch Black characters with stupidity and ignorance (for the sake of humour) or helplessness and childlikeness (for the sake of pity).

It seems this groom did not speak a West Indian creole dialect and Byron asked him to speak this way simply for his own amusement. That Byron is referred to by the groom as ‘master’ does not in itself indicate that the man is enslaved. Many servants of this period would refer to their employer as ‘the master/my master.’ Let’s move on:

‘Being of the same colour, was a bond of sympathy between them and the groom, and he applied to me to give both these women quarters in the seraglio. I granted the application, and mentioned it to Lord Byron, who laughed at the gallantry of his groom, and ordered that he should be brought before him at ten o’clock the next day , to answer for his presumption in making such an application.’

‘At ten o’clock, accordingly, he attended his master with great trembling and fear, but stuttered so when he attempted to speak , that he could not make himself understood; Lord Byron endeavouring, almost in vain, to preserve his gravity, reproved him severely for his presumption. Blacky stuttered a thousand excuses, and was ready to do any thing to appease his massa’s anger. His great yellow eyes wide open, he trembling from head to foot, his wandering and stuttering excuses, his visible dread, all tended to provoke laughter, and Lord Byron, fearing his own dignity would be hove overboard, told him to hold his tongue, and listen to his sentence.’

It really does feel like Parry was playing racist bingo here. We’ve got the very picture of a stuttering and servile Black theatrical character and a favourite racist slur of Regency wits: ‘blacky.’ Because why would you call Black people by their actual names, right? It seems like Byron and Parry were thoroughly amused by the effect of their little trick, Byron could barely keep it together to continue the pretence.

‘His visible dread, all tended to provoke laughter.’

Here Byron and Parry clearly forced a scene in which this groom was reduced to a stereotype of a stumbling, stuttering, sycophantic Black servant that was so beloved by those writers of the period who fell upon racist tropes to deliver a laugh. That is sinister enough itself, but below we will see a suggestion that the groom might have been enslaved by Byron:

Byron died in 1824 at the age of 36.

Byron died in 1824 at the age of 36.‘I was commanded to enter it in his memorandum book, and then he pronounced, in a solemn tone of voice, while blacky stood aghast, expecting some severe punishment, the following doom. “My determination is, that the children born of these black women, of which you may be the father, shall be my property, and I will maintain them. What say you?” “Go-Go-God bless you, massa, may you live great while,” stuttered out the groom, and sallied forth to tell the good news to the two distressed women.’

‘While blacky stood aghast, expecting some severe punishment.’ This rather makes one question what severe punishments the groom had experienced before. And how hilarious to make someone who has experienced trauma fear a repetition of such a thing! But that is not the focal point of the paragraph. Byron asserts that the children of the Black women, as children of his Black groom, would be his property.

Perhaps, some might say, this was all a continued part of the racist joke. The groom wasn’t actually enslaved; Byron was simply carrying on the master/slave play scene he’d designed to amuse himself. I’m not absolutely sure if I buy that argument. And even so, what a weird fantasy to play out with a Black servant. I pity any Black women who came into his service — one would rather not imagine.

It seems to me, this Black groom possibly was kept enslaved by Byron while he lived in Greece. If this was just any Regency fellow, it would be interesting, but perhaps less significant; there were lots of slave owning Brits. But Byron is perhaps the most universally known man from the Regency Era; his name is etched into British popular culture. Even people who know nothing about literature or history tend to know of Lord Byron.

He was no less famous in his own time, and had quite the following of fans. We can imagine how Byron and his rowdy pals behaved towards Black people they happened across at home in Britain — particularly servants.

All this serves as an important reminder, while there was significant opportunity for relative racial equality in Britain, and the 1820s saw a huge push in anti-racist education and abolitionist activity, there were some influential people in society whose racism was brazen, bullying and shameless.

[image error]March 8, 2023

Character Driven #2 — Was Our Beloved Austen Too Severe Upon Lydia Bennet?

How — indeed — how will you be so severe upon this girl? To condemn her to carry and raise infant after infant at the slimy hands of a prolific child seducer — her own abuser — and a gambling addict. That is punishment! Even the adulterous and morally corrupt Maria Bertram is not fated to such a judgment. And what a life must await Lydia’s children — if they survive! And what was her heinous crime? Awful it must have been. Simply, she was very young, very stupid and she was a determined flirt. Put her down, I suppose you will say. She must serve as an example to others.

Is it a happy ending for Lydia Bennet?

Is it a happy ending for Lydia Bennet?Worry not. This blog shall not take the form of a dramatic monologue. Though, that would be rather apt; from a modern perspective, Pride and Prejudice is something of a grim tragedy when Lydia’s story is in the spotlight.

Lydia Bennet was very young, even by Regency standards. Although the age of consent was twelve, it seems that girls under the age of fifteen were generally thought too young to engage in relationships with adult men. I suppose, in a modern retelling, Lydia would be eighteen rather than fifteen.

Lydia Bennet has been raised in ignorance. We know from Lizzy’s conversations that their mother and father’s educational provision for their daughters was to provide them with the means to teach themselves.

“Your mother must have been quite a slave to your education.” LOL, thinks Lizzy to herself.

With no particular instruction in literature, theology, or philosophy, Lydia’s only guide for the world is the influences around her (Mrs Bennet et al.) and her own natural disposition.

Lydia Bennet’s behaviour goes on unchecked. This is really when Lizzy comes into her role as the MVP in Pride and Prejudice; she seems to be the only person concerned with Lydia’s behaviour and the consequences that might follow. In fact, rather than attempt to protect Lydia, her own father sends her away to a town filled with young men on the prowl in the hopes that it will teach Lydia a lesson; of course, it does, but it’s not the lesson he was thinking of!

Oh, Lydia!

Oh, Lydia!Austen presents Lydia as silly, vain and dangerously open in her manners towards men. Yet, Lydia’s being a victim of her neglectful upbringing is also very apparent in the novel; she’s really the perfect candidate to be groomed by a vile man like Wickham. Heck, even Lizzy gets taken in by his charms and she’s five years older and far more sensible!

So, does our beloved Jane Austen deal too harshly with Lydia? I think not. Whoa! Whoa! I know what I said earlier. And I meant it, I really do think that Lydia’s fate is really quite tragic; she’s left married to the man who groomed her, presumably to churn out baby after baby with little money and little support. Lydia will long feel the punishment of the misstep she took at fifteen, as will her innocent children.

In my ideal Pride and Prejudice, Lydia would return home, her parents having learnt their lesson, and she would spend many years educating herself and reflecting on her mistake, learning to be happy with herself beyond the admiration of men, until, fifteen years later, she would meet a sensible man who can look beyond that fateful error of her youth and love her for who she is today.

That, of course, would necessarily change many of the events in Pride and Prejudice, and not least, leaving Lydia debauched and unmarried; a troublesome fate for a Regency girl and all associated with her. Reasonably speaking, I believe that having Lydia marry the man who seduced her is the happiest outcome that could have been tolerated by Austen’s contemporary audience. In other literature of the period, there seem to be two common fates for ‘fallen women’ — they either die or marry the man who defaced their virtue — even in obvious cases of rape.

Maria Bertram has the unhappy, though less miserable, fate of going to live in obscurity with her annoying aunt as a punishment for running away with another man. But Maria was already married. She didn’t lose her virginity to Henry Crawford and that, I believe, is the significant factor in Lydia’s case.

Whatever Austen’s personal beliefs, I’m not convinced she could have written an ending for Lydia that didn’t involve her dying or marrying Wickham, not without changing the consequences for the Bennet family (especially Lizzy and Jane) and not that would have been acceptable to her peers. Marrying the man who groomed her as a child was the best outcome for Lydia in her time; something that is a disturbing reflection of the society in which our favourite sparkling romances originate.

I wish Austen could have given Lydia a second chance at making good choices, but the reality was, girls like Lydia didn’t often get second chances.

What are your thoughts? Was there another way for Austen to end Lydia’s tale? Would you like to see a Lydia Bennet retelling? Is there a Lydia Bennet retelling I ought to read? Or do you think that she was a foolish hussy who got what she deserved?

Until next time — adieu, my dears!

[image error]March 5, 2023

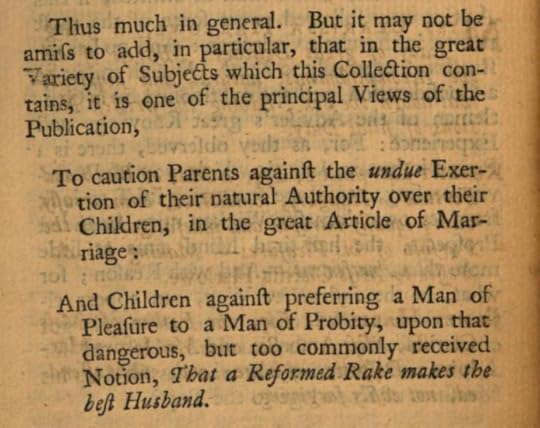

Clarissa Read-Along (Letters dated 1st-5th March).

Sit down, everyone. School is in session and Samuel Richardson has been labouring over these lesson plans for years. After two months of character development and setting the plot in motion, the moral lessons found in the letters of this epistolary tale are now in full swing.

The aim of entertaining readers in a work of literature, Richardson stated in 1748, is only permissible to the extent of its acting as a vehicle to moral instruction. Below is an excerpt from an original first edition copy of Clarissa.

To caution parents against undue exertion in arranged marriages and to warn children (young ladies) away from being charmed by rakes. As he notes himself, these are far from the only moral lessons that shaped the story of Clarissa.

Readers of reproductions of later editions might notice frequent footnotes in which Richardson, vexed and frustrated, takes to pointing out the moral messages so many of his readers seemed to overlook (or ignore).

I’m told that, with this novel, Richardson created the genre of ‘Rake Literature’ in which readers (primarily female) could experience the charming courtship and ugly realities known by women who find themselves picked out by a profligate man; all from the safety and comfort of their favourite armchair.

I don’t think Clarissa would have approved of ‘Rake Literature.’ It’s worth noting which books she thinks are worth reading.

I don’t think Clarissa would have approved of ‘Rake Literature.’ It’s worth noting which books she thinks are worth reading.This was not Richardson’s intention, though, I suppose in giving women a literary outlet for their curiosity about rakish men, it might have somewhat helped his true purpose.

Richardson’s moralising intentions are glaringly apparent in these letters. Many lessons can be derived from the behaviour of Clarissa’s family and that which Anna and Clarissa have to say about it:

“How can the husband of such a wife (a good man too!-But oh! this prerogative of manhood!) be so positive, so unpersuadable, to one who has brought into the family means, which they know so well the value of, that methinks they should value her the more for their sake? They do indeed value her: but, I am sorry to say, she has purchased that value by her compliances.”

In this novel, Clarissa is a singular character. She is the only person who, according to Richardson, acts faultlessly throughout. She is our blueprint, our model for how to behave with true virtue and sense. Clarissa is Richardson’s ideal young woman, though contemporary and modern readers alike have found complaints about her character, her logic, and her behaviour.

Anna appears to be universally favoured by modern readers. She is bold, witty, willing to disoblige authority (especially male authority) and says what she thinks; she seems more human — more relatable — than her clever and virtuous friend. Not only did she serve as a useful literary tool for Richardson, but Anna also provides a contrast that makes Clarissa’s wisdom and sense shine brighter (though it might not always seem that way to us).

Anna makes fun of Clarissa and her sensible and logical reasons for not being in love with Mr Lovelace.

Anna makes fun of Clarissa and her sensible and logical reasons for not being in love with Mr Lovelace.Though both friends are prone to emotional speeches and dramatic behaviour, Richardson typically presents Anna as arguing from a place of feeling; Clarissa from a place of reason.

To follow sense or sensibilities? Everyone in this story is grappling with that in their own way. The Harlowes, led by James, have been dazzled by improving their wealth and social status; Clarissa’s mother would go against the grain and do the right thing, but blind obedience, and not good moral sense, directs her actions.

The truly enlightened characters in Clarissa will find that the two align when virtue directs one’s desires.

Those are my thoughts on that week of letters. I’m really looking forward to unpicking more layers of characterisations next week. There’s so much happening in this book! Until then — adieu, my dears!

[image error]