Clarissa Read-Along (Letters dated 1st-5th March).

Sit down, everyone. School is in session and Samuel Richardson has been labouring over these lesson plans for years. After two months of character development and setting the plot in motion, the moral lessons found in the letters of this epistolary tale are now in full swing.

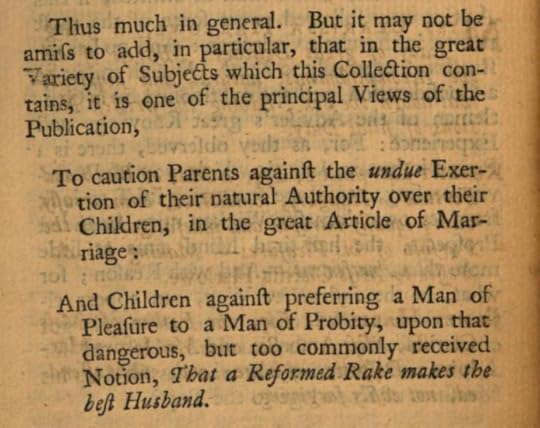

The aim of entertaining readers in a work of literature, Richardson stated in 1748, is only permissible to the extent of its acting as a vehicle to moral instruction. Below is an excerpt from an original first edition copy of Clarissa.

To caution parents against undue exertion in arranged marriages and to warn children (young ladies) away from being charmed by rakes. As he notes himself, these are far from the only moral lessons that shaped the story of Clarissa.

Readers of reproductions of later editions might notice frequent footnotes in which Richardson, vexed and frustrated, takes to pointing out the moral messages so many of his readers seemed to overlook (or ignore).

I’m told that, with this novel, Richardson created the genre of ‘Rake Literature’ in which readers (primarily female) could experience the charming courtship and ugly realities known by women who find themselves picked out by a profligate man; all from the safety and comfort of their favourite armchair.

I don’t think Clarissa would have approved of ‘Rake Literature.’ It’s worth noting which books she thinks are worth reading.

I don’t think Clarissa would have approved of ‘Rake Literature.’ It’s worth noting which books she thinks are worth reading.This was not Richardson’s intention, though, I suppose in giving women a literary outlet for their curiosity about rakish men, it might have somewhat helped his true purpose.

Richardson’s moralising intentions are glaringly apparent in these letters. Many lessons can be derived from the behaviour of Clarissa’s family and that which Anna and Clarissa have to say about it:

“How can the husband of such a wife (a good man too!-But oh! this prerogative of manhood!) be so positive, so unpersuadable, to one who has brought into the family means, which they know so well the value of, that methinks they should value her the more for their sake? They do indeed value her: but, I am sorry to say, she has purchased that value by her compliances.”

In this novel, Clarissa is a singular character. She is the only person who, according to Richardson, acts faultlessly throughout. She is our blueprint, our model for how to behave with true virtue and sense. Clarissa is Richardson’s ideal young woman, though contemporary and modern readers alike have found complaints about her character, her logic, and her behaviour.

Anna appears to be universally favoured by modern readers. She is bold, witty, willing to disoblige authority (especially male authority) and says what she thinks; she seems more human — more relatable — than her clever and virtuous friend. Not only did she serve as a useful literary tool for Richardson, but Anna also provides a contrast that makes Clarissa’s wisdom and sense shine brighter (though it might not always seem that way to us).

Anna makes fun of Clarissa and her sensible and logical reasons for not being in love with Mr Lovelace.

Anna makes fun of Clarissa and her sensible and logical reasons for not being in love with Mr Lovelace.Though both friends are prone to emotional speeches and dramatic behaviour, Richardson typically presents Anna as arguing from a place of feeling; Clarissa from a place of reason.

To follow sense or sensibilities? Everyone in this story is grappling with that in their own way. The Harlowes, led by James, have been dazzled by improving their wealth and social status; Clarissa’s mother would go against the grain and do the right thing, but blind obedience, and not good moral sense, directs her actions.

The truly enlightened characters in Clarissa will find that the two align when virtue directs one’s desires.

Those are my thoughts on that week of letters. I’m really looking forward to unpicking more layers of characterisations next week. There’s so much happening in this book! Until then — adieu, my dears!

[image error]