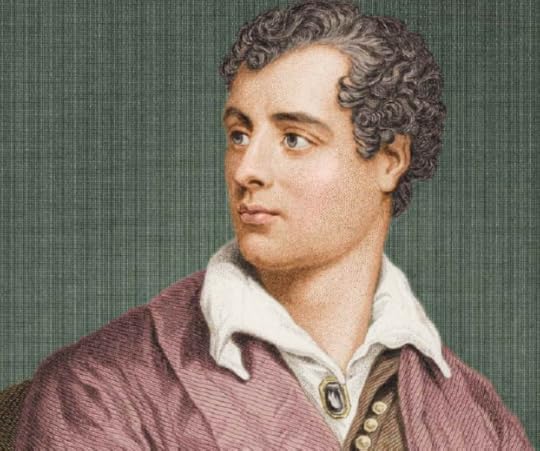

Lord Byron’s Enslaved Black Groom. Race and Regency #3

When prolific seducer, useless husband and deadbeat dad, Lord Byron, died in 1824, his friend William Parry gushed praise for the late poet onto the page just a year later, publishing, ‘The Last Days of Lord Byron’ in 1825. The intended effect, presumably, was to respect his lost friend with a book showing how funny and clever Lord B was. IDK. Honestly, ‘The Last Days’ makes Byron seem like the most insufferable human being who ever lived.

But we’re not here to discuss Byron’s general arseholery. Today, we shall be looking at what Parry’s book tells us about race and racism in the Regency Era through a vignette of Lord Byron’s Black groom:

‘Lord Byron had a black groom with him in Greece, an American by birth, to whom he was very partial (this man died in London a short time back). He always insisted on this man’s calling him Massa , whenever he spoke to him. On one occasion, the groom met with two women of his own complexion, who had been slaves to the Turks and liberated, but had been left almost to starve when the Greeks had risen on their tyrants.’

Almost immediately we’re met with a glimpse at what sort of treatment this groom experienced from Byron.

‘He always insisted on this man’s calling him Massa,’

The term ‘Massa’ is often found in British texts of the long-eighteenth century, representing how enslaved people in the British West Indies would say ‘master.’ Often creole or mock creole was exaggerated and used to sketch Black characters with stupidity and ignorance (for the sake of humour) or helplessness and childlikeness (for the sake of pity).

It seems this groom did not speak a West Indian creole dialect and Byron asked him to speak this way simply for his own amusement. That Byron is referred to by the groom as ‘master’ does not in itself indicate that the man is enslaved. Many servants of this period would refer to their employer as ‘the master/my master.’ Let’s move on:

‘Being of the same colour, was a bond of sympathy between them and the groom, and he applied to me to give both these women quarters in the seraglio. I granted the application, and mentioned it to Lord Byron, who laughed at the gallantry of his groom, and ordered that he should be brought before him at ten o’clock the next day , to answer for his presumption in making such an application.’

‘At ten o’clock, accordingly, he attended his master with great trembling and fear, but stuttered so when he attempted to speak , that he could not make himself understood; Lord Byron endeavouring, almost in vain, to preserve his gravity, reproved him severely for his presumption. Blacky stuttered a thousand excuses, and was ready to do any thing to appease his massa’s anger. His great yellow eyes wide open, he trembling from head to foot, his wandering and stuttering excuses, his visible dread, all tended to provoke laughter, and Lord Byron, fearing his own dignity would be hove overboard, told him to hold his tongue, and listen to his sentence.’

It really does feel like Parry was playing racist bingo here. We’ve got the very picture of a stuttering and servile Black theatrical character and a favourite racist slur of Regency wits: ‘blacky.’ Because why would you call Black people by their actual names, right? It seems like Byron and Parry were thoroughly amused by the effect of their little trick, Byron could barely keep it together to continue the pretence.

‘His visible dread, all tended to provoke laughter.’

Here Byron and Parry clearly forced a scene in which this groom was reduced to a stereotype of a stumbling, stuttering, sycophantic Black servant that was so beloved by those writers of the period who fell upon racist tropes to deliver a laugh. That is sinister enough itself, but below we will see a suggestion that the groom might have been enslaved by Byron:

Byron died in 1824 at the age of 36.

Byron died in 1824 at the age of 36.‘I was commanded to enter it in his memorandum book, and then he pronounced, in a solemn tone of voice, while blacky stood aghast, expecting some severe punishment, the following doom. “My determination is, that the children born of these black women, of which you may be the father, shall be my property, and I will maintain them. What say you?” “Go-Go-God bless you, massa, may you live great while,” stuttered out the groom, and sallied forth to tell the good news to the two distressed women.’

‘While blacky stood aghast, expecting some severe punishment.’ This rather makes one question what severe punishments the groom had experienced before. And how hilarious to make someone who has experienced trauma fear a repetition of such a thing! But that is not the focal point of the paragraph. Byron asserts that the children of the Black women, as children of his Black groom, would be his property.

Perhaps, some might say, this was all a continued part of the racist joke. The groom wasn’t actually enslaved; Byron was simply carrying on the master/slave play scene he’d designed to amuse himself. I’m not absolutely sure if I buy that argument. And even so, what a weird fantasy to play out with a Black servant. I pity any Black women who came into his service — one would rather not imagine.

It seems to me, this Black groom possibly was kept enslaved by Byron while he lived in Greece. If this was just any Regency fellow, it would be interesting, but perhaps less significant; there were lots of slave owning Brits. But Byron is perhaps the most universally known man from the Regency Era; his name is etched into British popular culture. Even people who know nothing about literature or history tend to know of Lord Byron.

He was no less famous in his own time, and had quite the following of fans. We can imagine how Byron and his rowdy pals behaved towards Black people they happened across at home in Britain — particularly servants.

All this serves as an important reminder, while there was significant opportunity for relative racial equality in Britain, and the 1820s saw a huge push in anti-racist education and abolitionist activity, there were some influential people in society whose racism was brazen, bullying and shameless.

[image error]