Abigail Ted's Blog, page 3

March 3, 2023

“There are no slaves in England.” American perspectives. Race and Regency #2

Sarah Baartman was held on display in London in 1810.

Sarah Baartman was held on display in London in 1810.One year before Jane Austen’s beloved novel, Sense and Sensibility, was published, three years after Britain abolished the trading of slaves, and thirty-eight years after the Mansfield judgment, Sarah Baartman was being held on display in London for the amusement of paying-customers who were allowed to poke and prod at her naked body.

The men who did this to Baartman claimed she was there of her own free will; historians think otherwise. It’s 1810, the age of consent is twelve, the last public beheading won’t happen for another ten years and Sarah Baartman is sexually assaulted in humiliating circumstances, daily, for the amusement of bored Londoners.

Here we have some details that add to our picture of Regency England. American chemist, Benjamin Silliman, offers another glimpse into life for Black (and South Asian) Britons in his 1810 book, A Journal of Travels in England, Holland and Scotland 1805–1806.

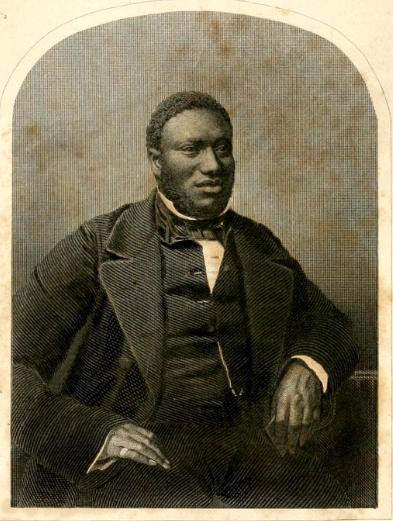

Benjamin Silliman in 1825.

Benjamin Silliman in 1825.When Silliman did a tour of Britain, he was surprised that Black and Asian people existed in society in much the same way as their White countryfolk. I rather wish he’d written more on his observations in this area, but, as it’s not a long excerpt, I shall give you all that Silliman said on the topic:

“ANGLO ASIATICS AND AFRICANS.

From the rag fair we went on board an American ship lying in the London docks. There we saw several children which have been sent, by the way of America, from India to England, to receive an education. They are the descendants of European fathers and of Bengalee mothers, and are of course the medium between the two, in colour, features and form.

I mention this circumstance because the fact has become extremely common. You will occasionally meet in the streets of London genteel young ladies, born in England, walking with their half-brothers, or more commonly with their nephews, born in India, who possess, in a very strong degree, the black hair, small features, delicate form, and brown complexion of the native Hindus.

These young men are received into society and take the rank of their fathers. I confess the fact struck me rather unpleasantly. It would seem that the prejudice against colour is less strong in England than in America; for, the few negroes found in this country, are in a condition much superior to that of their countrymen any where else.

A black footman is considered as a great acquisition, and consequently, negro servants are sought for and caressed. An ill dressed or starving negro is never seen in England, and in some instances even alliances are

formed between them and white girls of the lower orders of society.

A few days since I met in Oxford-street a well dressed white girl who was of a ruddy complexion, and even handsome, walking arm in arm, and conversing very sociably, with a negro man, who was as well dressed as she, and so black that his skin had a kind of ebony lustre.

As there are no slaves in England, perhaps the English have not learned to regard negroes as a degraded class of men, as we do in the United States, where we have never seen them in any other condition.”

Silliman was a teenager during these travels — though an adult when he wrote about them — and the culture shock is apparent. Without knowing more about his early views on slavery, it’s hard for me to exactly determine if Silliman is impressed or appalled by the relative equality possible for Black and Asian people in British society. What are your thoughts on his remarks?

Relative equality was possible, and — as shown in Silliman’s observations — it would not have been uncommon to see well-dressed Black and Asian Britons walking down the street arm-in-arm with similarly well-dressed White friends, family members or lovers in London.

We discussed last week that, throughout the long-eighteenth century, there was a growing trend of interracial marriages; this was purposely and consciously thought of as a singularly working-class activity. Thus, as Silliman points out, it was quite acceptable for Black men to form romantic relationships with White women of a lower social class than their own.

We might also assume it was acceptable for White men to form relationships with Black women of a lower social class. It was significantly harder for women to marry someone considered beneath their status without long-lasting social consequences; whatever their beau’s ethnicity might be.

It is important to note that when we discuss the social stigma of interracial marriage we are mostly referring to a specifically anti-Black and anti-African stigma.

Silliman reminds us that it was not uncommon for a White man of any rank in society to marry a South Asian woman.

With my own father being half-Indian, I found the comments about children of Bengali mothers and White fathers being accepted into any and all ranks of society particularly interesting. One can begin to imagine a truly diverse picture of the people walking the London streets in the Regency Era. When we imagine Mr Darcy and Mr Bingley taking a morning stroll in town, perhaps now we see the sketch of the world around them more clearly.

Another traveller to England, Samuel Ringgold Ward — though visiting in 1853 — offers us a Black perspective on this relative equality to be found in Britain.

Samuel Ringgold Ward

Samuel Ringgold WardWard has a lot to say about his experience in Britain, all detailed in his 1855 autobiography, Autobiography of a Fugitive Negro: His Anti-slavery Labours in the United States, Canada & England. Below are some excerpts:

“It should be, in America and in the colonies, regarded as a matter of importance, for a man wishing to improve both his head and his heart, to visit England. There is so much to be learned here, civilization being at its very summit.”

“Nor, I hope, shall I be considered wanting in gratitude…if I do not mention the name of every town in which I received kindness, and every family and every individual to whom I am indebted. The reason why I shall not do so is simply this: this book must have an end.”

Ward had a very pleasant time visiting England, and mentions his regret that he could not be treated with such equality and friendliness in the country of his birth. It is notable that Ward experiences this not just in London and other big cities, but other smaller towns in England too.

Sir Samuel Cunard — father of the modern cruise ship.

Sir Samuel Cunard — father of the modern cruise ship.It was on his journey to England that Ward reflects on something indicative of that relative equality we were mentioning earlier.

Though Ward’s ticket entitled him to the best of treatment, he was asked by Mr Cunard not to sit in the best dining room because of complaints from American travellers. Otherwise, Ward’s comfort was attended to (author of, Vanity Fair, William Makepeace Thackeray kept him company onboard). Mr Cunard’s explanation seemed to be that, while he personally hated racism, business is business. The comfort of White Americans was worth more to him than his personal convictions of equality.

This was something Ward recognised in the culture of British businessmen: they might, at one level, view him as an equal, but they did not believe Ward or other Black consumers had rights equal to their White customers. When it came down to it, money, and not morality, was the motivator.

That’s it for our exploration of Race and Regency today. See you next time!

[image error]March 1, 2023

Character Driven #1 — An Analysis of Captain George Osborne from Vanity Fair (1848).

Captain George Osborne in ITV’s adaptation of Vanity Fair.

Captain George Osborne in ITV’s adaptation of Vanity Fair.Welcome to my blog series, ‘Character Driven’ in which I will unpack my thoughts on various literary characters from the canon of classics. Today, I’ll be turning my thoughts back to the novel, Vanity Fair, published in 1848 by William Makepeace Thackeray; a favourite of my own, and beloved by many fans of classic literature. Spoilers included below.

Views on Vanity Fair’s resident bad boy, Captain George Osborne, vary in the extreme. From Team ‘I CAN CHANGE HIM’ — of which I am a longstanding member — to those more sensible among us who find his wandering eye and excessive sense of self-worth render him perfectly unamiable.

To my knowledge, Captain Osborne’s character was largely based on that of Captain William Booth from Henry Fielding’s novel, Amelia, published a century earlier in 1751. In both Captains we have a propensity for all the usual vices; smoking, hard-liquor drinking, gambling, infidelity, gambling, general financial imprudence and more gambling. Did I mention gambling? Good job they were both handsome, I suppose…

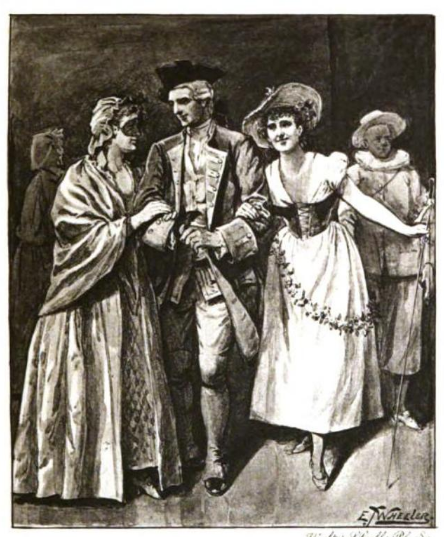

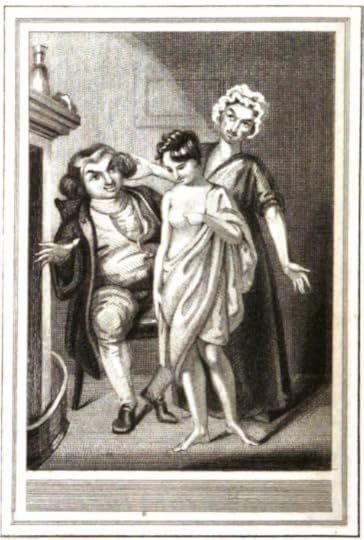

Captain William Booth with two young ladies hanging upon his arms.

Captain William Booth with two young ladies hanging upon his arms.The difference, I think, between the two bad boys is in the ends of their respective personal tales. Captain Booth’s character arc ends in his being revealed to be rather sad and pathetic; his poor family only saved from ruin by his long-suffering and quite perfect Amelia. Captain Osborne, however, is killed, the vision of bravery, before he can ruin his Amelia’s life entirely.

George Osborne is a much better sketched character than Booth; there are simply more layers to his story. Perhaps that’s why interpretations of his character vary so greatly.

That’s enough about the two captains. Now, I shall break down George’s character into the good and the bad. A good ‘bad-boy’ character must have a strong foundation (even if hidden) of at least some strong morals.

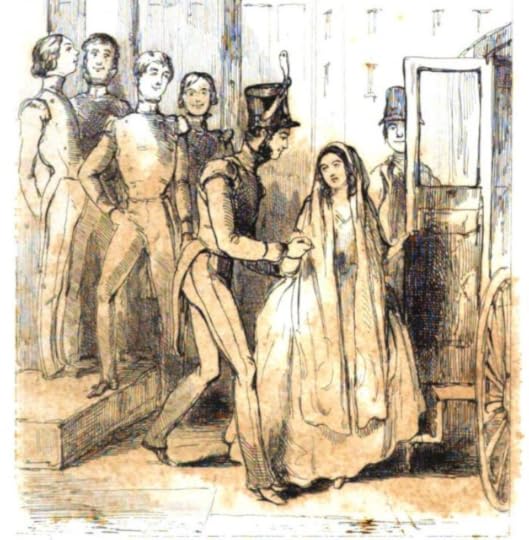

Captain Osborne and Amelia get married.

Captain Osborne and Amelia get married.George is self-obsessed. He is extremely vain and nobody loves George like George loves George. It’s hardly the worst thing a man can be, but it’s also not a good quality in a person, therefore, we shall add it to our list of bad characteristics.

George is supercilious. He doesn’t come from some ancient or honourable family, his father is an extremely wealthy stockbroker but his grandparents were very ordinary lowly people. Now the family has money, George wants to be part of the higher ranks of society and he doesn’t want to associate with anybody who is not of those ranks. This is, I think we will agree, a bad quality.

George had a sad and lonely childhood, one worthy of at least some pity. Details about George’s childhood are woven throughout the novel; we know that George went to boarding school where he was beaten and abused by the older boys. His father beat him too, which wouldn’t have been unusual for the time period but to a modern reader adds a level of personal trauma to his character. While these are not good things, they do make some of his flaws more understandable, so we shall put this in the ‘good’ pile.

His parents. We don’t know when George’s mother died but it was before the novel begins. Mrs Osborne enters the novel only in recollections of her tenderness towards George; the antidote to his father’s tyranny. His father materially provides everything for George yet appears emotionally abusive and pretty awful to his son. Again, all this makes George’s flaws more understandable, so it goes on the ‘good’ pile.

George is a loyal friend. He’s definitely not the best example of a fictional friend, but to his best friend he is loyal and open. Dobbin often calls George out on his terrible behaviour, and George does often listen, take heed and take the advice of his well-meaning friend. This is undoubtedly a good quality.

George can be icy cold. Amelia and George were betrothed from childhood and for much of their engagement he would have been either an adolescent or an adult and she would have been a child. It doesn’t seem strange to me that he is (at best) indifferent to a girl he never chose to marry. It doesn’t surprise me and I don’t think it makes him a bad person.

But he does take this one step further. He’s emotionally cold, not very nice to Amelia and he’s rather embarrassed by his relationship with her; he doesn’t want to be seen out with this girl and he certainly doesn’t want his friends to know that he’s engaged to Amelia. She is very sweet and adores him and he hardly thinks of her. A bad mark of his character.

George is a wannabe Casanova. It’s unclear how successful he is with the ladies, but he tells his friend of his plans for having scandalous affairs with different women before he marries Amelia. Even once he is married, he is still chasing after other women, buying them gifts, lavishing them with praise and admiration and completely ignoring his darling, sweet wife. Thumbs down, George.

George loves all of the vices. It’s very difficult to have a good bad-boy character without some vices in there, and he’s got them all. Smoking, drinking and gambling; the perfect trio for any bad boy. I don’t think these things are inherently bad qualities, but they do all feed into his bad-boy character.

He’s respectful (in some ways). You have to read between the lines to pick this out, but George does not push boundaries with Amelia before they are married. They don’t tie the knot until he’s 28 years old and Amelia has been an adult (and pretty) young lady for several years. Despite being presented as a licentious Casanova, and having frequent opportunities of Amelia’s private company, there is no hint that he attempts to coerce, manipulate or pressure her into premarital shenanigans. Perhaps this is a reflection of social conditioning, or that the consequences of doing so would be too severe. Still, he’s no Mr Wickham, I shall count it towards the good in him.

Brussels. You know what I’m talking about. George is called off to war and he takes Amelia with him only a few weeks after they are married. The whole time they are there, he ignores his patient wife and instead chases after Amelia’s best friend, Rebecca. He tells Becky how beautiful she is, buying her flowers, buying her gifts, all while wasting away what little money he has. The night before he marches off, Amelia spends her evening crying at a ball because of how horribly George is treating her. Bad show, George!

George is heroic. His first act of heroism is in defying his father to honour his commitment in marrying Amelia; an act that was romantic and gutsy. When called to battle, George has no fear, we know that he behaves bravely while fighting. Courage, I shall place among his good qualities.

George is very remorseful. Just before his exit from the book, George has a Shakespearean moment of realisation; Amelia is perfect and he’s treated her horribly. George runs home to his wife and they share many tender hours before he leaves for battle. Later in the novel, we learn that, just before he was shot, George’s last thoughts are of Amelia and regret for the foolish note he gave Becky. He asks his best friend to care for Amelia should George be unable to return to her.

George is dead. This is, I think, George’s most redeeming quality because he’s unable to undo the good qualities he develops just before his death. Unlike Captain Booth, George dies at the high point of his character and when Amelia seems most in love with him. A true tragic hero must die after he’s realised his own flaws and follies. This was very clever of Thackeray. In dying, George gives Amelia and their son the freedom to have a life that had a truly happy ending. Being dead is George’s best quality.

That’s all on my deep dive into Captain George Osborne for now. What are your thoughts on this character?

[image error]February 23, 2023

“A White Woman in Want of a Black Husband.” Race and Regency #1

Welcome to the first in my series, Race and Regency, in which I will share excerpts from Regency Era publications (I’m referring to the broader ‘long-Regency’ e.g. 1795–1837) that relate to race and/or racism.

To begin the series, I’ve got a satirical letter published in The Rambler’s Magazine. The Rambler’s (not to be confused with the very morally upright ‘Rambler Magazine’) existed to divert and humour learned gentlemen with all sorts of articles and images designed for their amusement; often lewd, though not always.

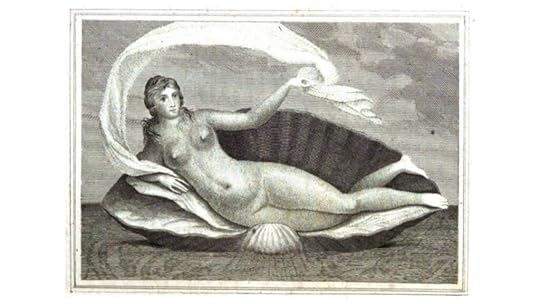

An illustration entitled, ‘Venus’, from this 1822 edition of The Rambler’s.

An illustration entitled, ‘Venus’, from this 1822 edition of The Rambler’s. An illustration entitled, ‘Poor Maria burst into tears’, from this 1822 edition of The Rambler’s.

An illustration entitled, ‘Poor Maria burst into tears’, from this 1822 edition of The Rambler’s.Below is a satirical letter published in an 1822 edition, supposing to be written by a female reader desperately seeking advice. It presents to the audience a familiar and tired joke at the expense of Black men and interracial couples. I’ll leave my explanation there and allow you to read the letter for yourself.

A letter published under the Eccentricities section of, The Rambler’s Magazine: Or, Fashionable Emporium of Polite Literature…(1822):

‘To the Editor of the Rambler.

A WHITE WOMAN IN WANT OF A BLACK HUSBAND.

“Sir, I want your advice.” — -HAMLET.

I am in a sad predicament: indeed, I shall be lost without ad- vice. I have, and I do not know why, for love is of every co- four and complexion, fixed my affections upon- Spare my blushes, I pray For I tremble to say; But my trembling I’ll stop if I can, Lord, sir, what think you? I love dearly, and true, A six-foot high, lovely BLACK MAN. He is not a man of consequence, but has made some noise in the world, for he is one of the king’s trumpeters, and has the ho-nour of blowing up Pall Mall every court day!

People say the nose on his face is flat-like a piece of dirty putty stuck upon a black grave-stone: that his eyes are “whitey-brown” — and looking any way but before him: that he is “pigion-breasted, thin-thigh’d, buck-shinn’d, and splay-footed.” All this may be true: they see not with a lover’s eyes. His form is spoiled by the ugly robes that cover him, but he has that WITHIN which surpasseth shew! For I have seen, and carefully observed when he retired, for necessary reasons, to the stable yard, near to my window, all his great qualifications to make a good man, and render the marriage state happy!

Pray, sir, give me your opinion. Shall I commit a sin in mar- rying a blacky for the sake of his trumpet, which is so long, strong, and fine in its execution, as to charm all that witness and experience its effect. We are all descended from Adam; our propensities are the same; Caribbees, Ashantees, Gentoos, and Hindoos, all made of the same flesh and blood, all got souls to be saved and fancies to be tickled, and if there is no moral harm in it, why should I not have my whim gratified?

I remain, sir, yours, &c.

WINIFRED WISH-FOR-IT.

Near Pall Mall, July 24.’

So, there it is.

Ha! What a hilarious and original joke, indeed! There was Winifred Wish-for-it, who would fain have had the reader believe that she thought ethnicity should be no reason for objecting to a match of love, that we are all human and on an equal footing, only to reveal the lecherous truth behind such declarations; the size of his genitals is to answer for her infatuation with this Black trumpeter!

At a surface level, this plays into stereotypes about Black men and interracial couples that still very much exist today: a Black man’s value to a White woman as a romantic partner must be his penis.

Let’s place this letter within the context of the time. It’s 1822, Black people throughout British territories are reduced to the place of disposable objects, the sexual abuse of enslaved people is pervasive; infants, boys, girls, women and men are the victims. London is now a truly multicultural city, the capital reflects the empire. Because non-White people are most likely to be poor, interracial relationships are most common amongst the working classes. Unlike France, Britain doesn’t legislate against its Black population, in fact, on the surface, all are equal here.

It’s social shaming we Brits do best. How can we deter the middle and upper classes from engaging in the working-class practice of interracial marriages? We can make them synonymous with sexual debauchery! It is of national importance that the lines between the classes never blur.

When this letter is placed within the context of the hyper-sexualisation and dehumanisation faced by Black people at all levels of society, and the vicious social reaction against the growing trend of interracial marriage, it’s evident with what vigour this gentleman’s magazine was punching down.

There’s a lot going on in this edition of the magazine, and we must remember that the editor and the letter writer are the minds responsible for this. It’s likely some readers would have thought it in poor taste, or even noted the racist sentiment. There are letters in support of abolition, and even those celebrating African and native women for their good-nature and natural virtue. It really does reflect a range of views.

It’s interesting though, isn’t it? We can almost imagine the liberal-minded, abolition supporting young gentleman at the university who makes these sorts of jokes with his friends over a pint. It gives a picture of the various shades of Regency thought on race and racism, and offers a small insight into the prejudice faced by Black Britons and people in interracial relationships.

What are your thoughts?

[image error]February 19, 2023

Clarissa Read-Along (Letters dated 20th-27th Feb).

Clarissa by Samuel Richardson (1748/1749) 12-month read-along and cooperative analysis.

Hello! After a month-long break we’ve finally got some more letters to read. Prepare yourself, there’s quite the stack of letters coming our way in March. February, I think, will give us a gentle(ish) return to Clarissa’s life and letters.

James and Bella Harlowe from the 1991 BBC adaptation of Clarissa.

James and Bella Harlowe from the 1991 BBC adaptation of Clarissa.As well as a video unpacking my thoughts on the letters from each month, I’ve decided to share my thoughts in writing (here) after reading each letter. My main focus tends to be character analysis, though I’m also a fan of unpacking narrative style and structure. Feel free to chime in below with your thoughts on anything; there will be lots of things I’ll miss, I’m sure.

As you know, I’m reading an eBook copy of the third edition which does differ somewhat from the original first edition (only available in paperback). But I don’t think this will present an issue until much later in the book. You might find your dates for the letters vary slightly if you’re reading the first edition.

The dates for the letters in February are:

Letter 7 — Feb, 20th.

Letter 8 — Feb, 24th.

Letter 9 — Feb, 26th.

Letter 10 — Feb, 27th.

Letter 7. Miss Clarissa Harlowe, to Miss Howe, after her return from visiting Miss Howe. Harlowe-Place, Feb, 20th. In which Clarissa describes the severe scene upon her sudden return home from Anna’s house.

I said things would take a sudden dark turn after January, but I’d forgotten quite how sudden that turn was. Oh, Clarissa, you poor babe! And aren’t James and Bella the worst? It’s pretty clear that there’s a strong sibling rivalry here and it seems that the special notice to Clarissa in her grandfather’s will has pushed her siblings into wanton cruelty.

In later letters, it becomes clear that Clarissa has been kept on a pedestal for much of her life; considered the wisest, the prettiest, and the godliest by all her family. Even so, James and Bella’s determination to mortify Clarissa’s pride in the cruellest way is rather stomach-churning.

Here the weeping, dizzy spells and limbs-beyond-control begin; Clarissa is a character of great mental strength, but her person often seems to fail her. Both relatable (as someone with many physical symptoms of anxiety) and interesting as a reader. There’s a lot that could be said about the way Richardson presents female strength; it is, I think, done in such a way that does not challenge masculine strength but undermines it with a powerful display of weakness. Only the most depraved of men could persevere in persecuting a woman reduced so visibly.

Remember, this is Richardson’s blueprint for the perfect Christian woman. Clarissa is, in his mind, the sage upon whom every young lady should model her own behaviour.

“I could easily answer you, Sir, said I, as such a reflection deserves: but I forebear.”

Despite the ill-treatment she is met with, Clarissa behaves in a rather servile and submissive way. She is determined to be cheerful and do whatever she can to please her family, even her horrible brother and sister.

Through the extreme niceness of her own manners, Clarissa renders her family crueller in the eyes of we watchers. We would perhaps feel differently if she had matched the tone she was met with, if she had too embarrassed her brother and put everyone in their place. This is the key to Clarissa’s ‘superpower.’

What are your thoughts on this letter and the characters and events involved?

[image error]