Jeannine Atkins's Blog, page 16

March 21, 2014

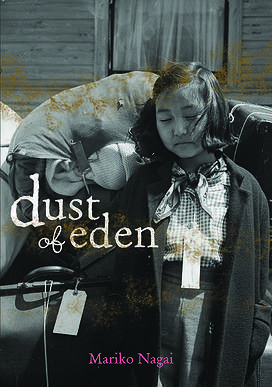

What I’m Reading: dust of eden by Mariko Nagai

Filled with images of red roses, dry earth, and barbed wire, Mariko Nagai shows the beauty within broken hearts in this verse novel that follows the story of a girl who feels more American than Japanese even as she leaves behind a best friend, an orange cat, a boarded-up house, and “Seattle with its sea smell” to go with her mother, grandfather, and brother to an internment camp. dust of eden begins with Mina Masako singing with her Sunday school when a man bursts in to announce, “The Japs bombed Pearl Harbor.” When the children return to their music, “…we were no longer singing as one.” The next day in school, immediately after the teacher speaks Mina’s name for the roll call, she mentions Pearl Harbor, and while Mina feels American, she knows the eyes on her don’t see that. She learns to hear the pause between “Jap” and “anise.”

While Mina reacts mostly with fear as her newspaperman father is put in jail, her older brother is angry. The adults seem to Mina to be play-acting that all is well. Eventually the family is told that they can bring two suitcases – we get echoes of this with verse in couplets – to an interment camp. Mina hates to leave behind their old orange cats who likes “to have his ears/ pulled gently… He grew up drinking/ miso soup…” There’s a moving goodbye to her best friend as they leave the house with furniture covered with white sheets and the cherry tree that had begun to bud.

The family first stays at a former fairgrounds pounded down by horse hooves, then move to a still more distant relocation camp. There, everyone spends a lot of time in lines, and Mina is schooled sitting at a picnic table placed indoors. I liked how most of the verse novel was structured through Mina Masako’s voice, with sometimes her thoughts, letters to her father or best friend, lists, or school papers. The intimate feeling reminded me of a journal, with poems identified by dates instead of titles. At the end, we get letters from her brother who enlisted and went overseas, a plot element that stirred tensions in the family and showed a country that locked up some Japanese Americans while taking others as soldiers. This gave us a bigger picture than we’d have otherwise, but I felt a bit as I do when reading the end of The Secret Garden and hear Colin instead of Mary Lennox: Can’t we stick with a girl we’ve come to love?

Not that this keeps The Secret Garden off my list of three favorite books, or will keep me from recommending dust of eden. In Why I Read, Wendy Lesser’s quotes Randall Jarrell as defining a novel as a prose work of some length that has something wrong with it. We pick and move on. And at the end of dust of eden, Mina Masako is still there, a few years older, with her voice and sense of self steadier and less innocent. So is a strong family, somehow made stronger through friendship and hope. Always, carefully chosen words glisten.

For more Poetry Friday posts, please visit Julie Larios at The Drift Record.

March 17, 2014

If at First … Finding a Picture Book’s Right Title

Titles can suggest the setting, a main character, a mood, or a theme, and with even some of that wanted in a few memorable words, authors may get them wrong at first. The Very Hungry Caterpillar gives us color, food, and an introduction to numbers, days of the week, and metamorphosis. We’d have missed much of that if Eric Carle’s editor, Anne Beneduce, hadn’t suggested he change his first idea, which was A Week with Willi Worm, thinking caterpillars are cuter. A good trade of alliteration for the chance of transformation.

Where the Wild Things Are by Maurice Sendak began in 1955 as Where the Wild Horses Are, but his editor, Ursula Nordstrom, pointed out that he couldn’t draw horses particularly well. So he turned to Wild Things, with some inspiration from Brooklyn relatives who’d terrified him as a child. Still, much work was ahead until the 1963 publication of his classic. Maurice Sendak said, “I’ve never spent less than two years on the text of one of my picture books, even though each of them is approximately 380 words long.”

Robert McCloskey spent about a year to write the 1,152 words in Make Way for Ducklings and another year or two working on the drawings. In New York, he visited the Museum of Natural History, but also bought ducks at the farmer’s market, gave them a place in his bathtub, and followed them around his apartment with tissues. He held up the swaddled ducks to see what they looked like from beneath, and set out dishes of wine to slow them down enough to draw. His first title was Boston is Lovely in the Spring, but it seemed to occur to the assistant of his editor, May Massee, that neither the word lovely nor spring was as likely to grab a young reader a much as duckling, and a command has more energy than a statement. She came up with the title that suggests the connection between people and the duck family.

When Paris was invaded by Nazis in 1940, Margaret and H.A. Rey, who were German Jews, fled on bicycles with the precious few things they could carry, including several manuscripts, one of which was about a monkey. The couple made their way to New York, where editors admired the curious monkey, but weren’t keen on any species of boy named Fifi. His name, and the title, was changed to Curious George, though when published in Britain, it was changed again to Zozo, rather than possibly stir scandal by having a monkey bear the name of the king at the time.

And not every editor will be one who sits behind a desk. Opinions may come from what some marketers call focus groups, but we might call story hour or the dinner table. Virginia Lee Burton, whose first book was turned down by thirteen publishers, was uncertain how to end Mike Mulligan and His Steam Shovel until a twelve year old family friend suggested the imaginative ending that the steam shovel Mary Anne, who had no logical way of digging herself out, become the happy furnace in the town hall basement. In the published book, a boy wearing green overalls comes up with the idea. It’s charming to see the asterisk and footnote: Acknowledgments to Dickie Birkenbush.

Much of what I know about the history of children’s books draws from the dedicated research and writing of Anita Silvey and Leonard Marcus. I thank them for their work which reminds me that it’s rarely if ever a short road to any book. Everyone needs time and help.

March 14, 2014

Poetry and Science for Children

This week one of my students wrote of her shock to see Dr. Seuss and Shel Silverstein listed among possible topics for poetry papers. “After four years of English credits and two years of AP English, I had completely forgotten that a poem can still be a poem without causing me to wonder whether I was intellectually inept midway through reading it.” Stephani Spindel went on to analyze the humor in in Where the Sidewalk Ends. She noted that sometimes a poem is just about pancakes, which is fine, and how as a child the collection gave her lots of chances to laugh and triumphantly turn the pages. She described the path to arriving at the poem that gave the book its title, an echo which even as a child told her that this poem was important, more serious than the others, and made her think in a new way.

All in all a wonderful paper, but that line about poetry leaving her feeling outside brought tears to my eyes. There’s long been a rough transition from babyhood, where chanting and rhyme may often begin a love for language, and childhood’s playground rhymes, to high school classes where students learn to ”tie the poem to a chair with rope/and torture a confession out of it,” as Billy Collins writes in “Introduction to Poetry.”

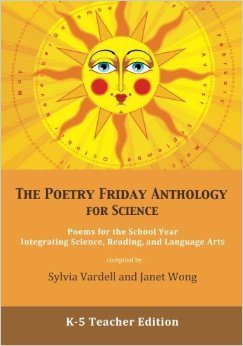

One way to keep the attention of students may be by blurring the divisions that grow in schools between the arts and the sciences. A wonderful aid to opening rather closing opportunities is the latest and most ambitious addition to the Poetry Friday series edited by Sylvia Vardell and Janet Wong. The Poetry Friday Anthology for Science gives readers plenty of humor, along with topics such as observation, space, machines, water, and force, motion, and energy. Sylvia Vardell notes that first and foremost, the poems should be enjoyed, but as with the other Poetry Friday books, she suggests ways for teachers to easily integrate readings into the classroom, linking poems to other poems or books with similar themes, providing questions for discussions, and suggesting ways to present the poems. For instance, for Douglas Florian’s poem, “Earth’s Tilt,” she suggests the teacher stand slightly tilted when reading, and offers a youtube link that explains how the earth’s tilt affects the seasons. And for my poem “Becoming Butterflies,” she suggests making a mock butterfly from tissue paper, and links to a time lapse video showing stages of metamorphosis.

You’ll find poems by a range of star poets, some of whom I’m happy to call friends, framed by quotes from luminaries such as Marie Curie, Albert Einstein, and Mary Oliver. Some poems in the collection address the scientific method or science fairs. I particularly enjoyed Eric Ode’s “Science Fair Project,” in which the narrator goes from being sure to win a ribbon to contemplating a teacher who “I bet she’s holding grudges. /My project ate my tri-fold/and then seven of the judges.” Other humor was gentler and nicely integrated with more serious tones. I loved the challenge of composing a biography in twenty lines, and wrote about entomologist Henri Fabre in “Classroom in the Meadow,” physicist Marguerite Perey in “Elemental,” and Florence Nightingale’s pioneering use of pie charts in “Nursing Math.” I also had fun naming the teacher in “Playground Physics” Mr. Newton. I was pleased that my husband, my first reader, got the joke without me mouthing “Sir Isaac.” I think many children will miss it, but I hope one beautifully nerdy kid gets to be a class star by pointing it out.

For more Poetry Friday posts, please visit rogue anthropologist.

March 11, 2014

Black Women & the Arts: A Conversation with Toni Morrison, Bernice Johnson Reagon, & Sonia Sanchez

Last night the Mullins Center at UMass-Amherst rang with a saxophone solo by Frederick Tillis and the Voices of New Africa choir singing “Wade in the Water,” before introductions by John Bracey of the sponsoring W.E.B. Du Bois Department of Afro-American Studies to three brilliant women who clearly cherished each other. Poet Sonia Sanchez took the role of asking the others questions, which provoked novelist Toni Morrison to ponder, while singer and activist Bernice Johnson Reagon sometimes replied by bursting into song, often inviting the audience to sing along. She spoke of coming from a church tradition in which one person started a line, which others took up, changed, or developed. Bernice Reagon shaped songs sung by slaves into more contemporary freedom songs and reshaped present day stories; for instance, in the 1970s, after over-hearing men making jokes about a woman who was assaulted and killed in self defense, she wrote a song in which many found common ground in the story of Joan Little.

Sonia Sanchez, who as a visiting writer at Amherst College years ago, helped found the Black Studies Department, asked probing questions, quoted poetry, and sometimes chanted and sang, too. Toni Morrison did not sing, but she spoke of her love for the sound of language, the way her family told stories, and changed them, and the ways she hopes readers will participate in the words she writes, to bring themselves into the text as they would to a song. Readers change the meanings she sometimes creates by invoking ancestors. The theme of memory came up often, as it does in Morrison’s novels, including Beloved. She distinguished between memory as a sense of what you believe happened, while re-memory is digging to discover more, to cloak or shape what might have happened with language. While speaking, she twisted her hands as if she were trying to rearrange a sentence between them, getting closer to “the picture you’re trying so hard to reveal.”

“Who do you write for?” Sonia Sanchez asked. Toni Morrison replied, “First of all, the people in the texts.” She said she needs to know her characters’ names before she can step inside them, and then “they will tell you everything,” while, she, as author selects, for often “they’re not interested in anything but themselves.” She mentioned that Pilot in Song of Solomon might have taken over the whole book. Her first challenge with that novel was trying to write about men, after having written two novels focused on the lives of women. Her father, whom she’d adored, had recently died, and she asked herself: I wonder what my father knew about these men. That question brought her some peace and confidence that grew into the novel. Which, like her other books, achieves what she says art should do, combining what’s “unquestioningly political with irrevocable beauty.”

It was one of those nights when you smile at strangers in the parking lot. Unforgettable.

March 10, 2014

In the Pink

Amidst todays errands, I stopped at the Smith College spring bulb show, “In the Pink,” where the Botanic Gardens is selling t-shirts celebrating A Century of Women in the Topsoil. Cameras clicked as people smiled, sniffed, spring-hoped, and snow-forgot.

I reluctantly buttoned my coat to leave, but the outside was beautiful, too.

March 3, 2014

Women in Print

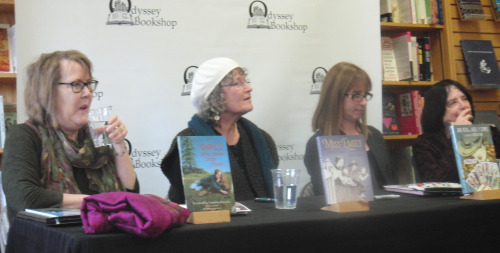

It was lovely to see friends and girls I didn’t know but were decked in ladybug boots, puffy pink jackets, or Girl Scout vests at The Odyssey Bookshop yesterday, where, in honor of Women’s History Month, I was part of a panel focused on writing about women. Jane Yolen, who is celebrating fifty years of publishing, and her daughter, Heidi Stemple, spoke about collaborating on Bad Girls: Sirens, Jezebels, Murderesses, Thieves & Other Female Villains. Jane also spoke about her passion for folklore and the tradition of reinventing fairy tales, and how by writing a book such as The Curse of the Thirteenth Fey: The True Tale of Sleeping Beauty, she learned more about the story and more about herself. Burleigh Mutén talked about what inspired her to showcase a more playful, nature-loving side of Emily Dickinson in her verse novel, Miss Emily. We all discussed the layers of research and revision, the need to go down lots of unfruitful paths while ferreting out material, and create more roads to nowhere as we draft, then explore of all of these for just the parts we need.

The final question from our host, Hannah Mouschabeck, was: Who is your favorite woman from history? But we love so many! One. Jane said within the world of politics, it would be Eleanor Roosevelt. Heidi went for Mata Hari, even though, she said, she wasn’t really a very good spy. Burleigh said Artemis. And I chose my Grandmère, who wasn’t famous, but inspired me with the way she loved painting even though her work wasn’t known beyond her family and friends.

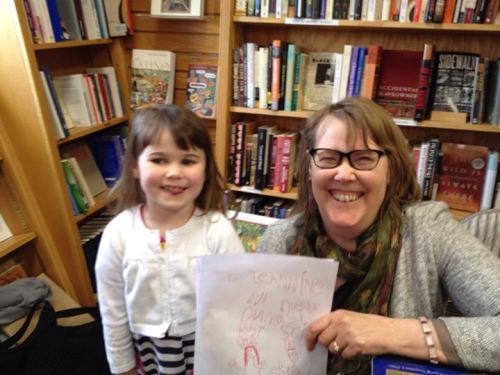

Afterward we signed books, always fun, but the highlight for me was meeting the daughter of a former student, who came not just to be inspired, but arrived with a book she’d already written, and gave it to me. Phoebe’s note here shows a scientist and a princess, or a princess scientist. It was great to nod to the past, and glimpse, through Phoebe, a glorious future.

February 25, 2014

Finding Structure in the Shambles

When I brought a draft of my verse novel to my writing group, I knew it had problems. I was unsure about the narrative, and had thrown in too many plot turns, all of them with fuzzy edges. I hoped one would prove of use. Of course my friends said, “What’s the main arc? You’ve got a few here.” They could make out some blurry signs of a way through, but these were half-hidden behind other signs pointing every which way.

Even a few unnecessary wrong in narrative poems can easily trip readers into the wrong direction. Now I’m clipping stray elements so the main path stands out, but I feel a bit bruised as I cross out stanzas and entire poems. I’m reporting, not complaining, much. Knowing I faced plot problems was exactly why I gave the manuscript to my group. If we want help fixing a problem, we have to show the imperfect draft or a badly bruised knee, and we’re embarrassed, apologetic, and a little stunned.

My writer’s group helped me see the faint lines between what’s subtle and what’s plain obscure, which means more revising. When writing poetry, one of my main rules is to pare everything I can. Less is more, but it hurts when you made the More. As I hunker over the project presently titled the Great Untangling, I put myself a bit under quarantine. It’s no time to make big decisions, or even, say, critique a friend’s manuscript. I’m managing what needs to be managed in life and reminding myself that just as I want an arc in this book, there’s an arc to this aching. It rises, and it will find a way out with time and tea and toast. It hurts to cut, but it feels good to start to see the clearer shapes of what is left.

Going back and around again, in the new wreckage I’ve created, lets me see the whole shape more clearly than I could than when I’d been moving never exactly straight ahead, but intent on forward motion. Going back to trim and shuffle helps me see every battered wall. It’s by looking back we may recognize a structure, and often build meaning, too, which we missed in our first glances at objects. We have to kick around the details we put in, or lift them up to smell or chew them. We go a long way until we know all that one coffee cup, weed, bicycle, or bent helmet might be, or why it stuck around.

Sure, I’m a little jealous when I hear of Super Supportive writing groups, who can’t find a flaw in the work, besides maybe an errant comma. All that cheering must feel good. But I wouldn’t trade my group in a million years. They urge me to kick holes, then pile up the dust,which leaves spaces to find surprises. These may be the same holes where a good reader’s view and mine collapse into one. Where my stories can become another’s. I’m again writing into the unknown, page by page, then sometimes line by line and word by word, which lets me see something prettier than the photo I shot above. Am I getting closer? I don’t yet know. But I’ll trust my writing group for the truth.

February 21, 2014

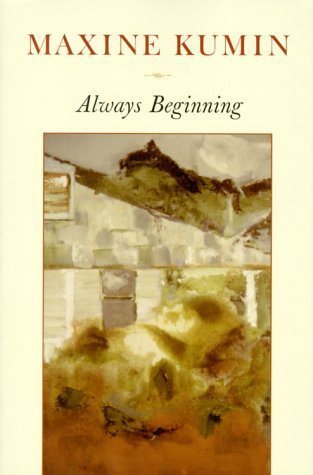

Always Beginning: Maxine Kumin and Rainer Maria Rilke

The recent death of Maxine Kumin sent me to her poems as well as a collection of essays called ALWAYS BEGINNING published when she was in her seventies. She looks or looks back at a good life filled with reading and writing poems, teaching, children, grandchildren, raising horses, growing green beans, and more, including speaking out against some people’s tendency to idolize poets who are suicides, despite, or because, one of her best friends was Anne Sexton, who died by her own hand. Her memories of Anne include collaborating on four books for children and days in the 1960s when they left their phones off the hook and whistled if they wanted the other to respond to some lines of a poem. I loved learning about how Maxine Kumin attended a reading given by Alice Walker who urged every woman present: “Each one save one,” meaning each woman writer should save another from anonymity. Maxine Kumin had strong political convictions she wanted people to know, while spending most of her time in rural New Hampshire. She wrote, “Poetry’s like farming. It’s/ a calling, it needs constancy.” In this collection of essays, she praises Robert Frost, Wallace Stevens, Elizabeth Bishop, and the teachers who had her memorize poetry in fourth or fifth grade, giving their students “an inner library to draw on for the rest of our lives.”

This volume also shows her love for the work of Rainer Maria Rilke. Here’s the line which gave her the title. “If the angel deigns to come, it will be because you have convinced him, not by tears, but by your humble resolve to be always beginning: to be a beginner.”

Some words from Rilke’s Ninth Duino Elegy inspired the title of one of Maxine Kumin’s volumes of poems. Here’s what she typed and pinned over her writing desk: “For we are here perhaps merely to say: house, bridge, fountain, gate, jar, fruit tree, window – at most, pillar, tower? But to say them … to say them in such a way that even the things themselves never hoped to exist so intensely.”

Thank you, Maxine Kumin, for nudging me to read more of Rilke’s work as well as yours. And something to aim for in my verse. For more Poetry Friday posts, please visit Karen Edmisten* The Blog with a Shockingly Clever Title.

February 7, 2014

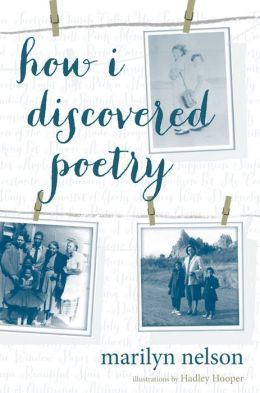

What I’m Reading: how i discovered poetry by Marilyn Nelson

how I discovered poetry by Marilyn Nelson is written in forty unrhymed sonnets, showing a life based on her own, but with added research and imagination, during the 1950’s, when she grew from four years old (as she is in the picture taken by her father below) to fourteen. The first words are “Once upon a time,” and we hear the small child in bed amusing herself not only with the idea of time, but prepositions. The next poem is set in church, where upon hearing that Lot and his wife flee, she imagines companionable fleas within the Biblical story.

As the narrator grows up, the poems told in first person reflect what she learns within the fourteen line frames that, one after another, with line illustrations by Hadley Hooper and a few black and white photographs, seem like blankets pinned at the corners by the four members of the family. The father’s work as one of the first African-American career officers in the Air Force, mean they travel a lot. Her mother teaches second grade and oversees what happens to her two daughters in classrooms where Marilyn sometimes “has the darkest eyes in the room” and sometimes is in an all-black classroom. She shows how both places have their pleasures and difficulties. She sometimes briefly reflects on what she overhears about integration and segregation, thoughts broken by a child’s common wish for a pony. As she grows older, her mother brings home some Africans from grad school and tells her daughter “these are our people.” As the growing poet puts away the supper dishes, she asks herself “who are not my people.”

A developing awareness of the implications of race is a theme, the failures and small triumphs of justice on school playgrounds (we get some seesaw imagery), but the collection is as marked by the travel of a parent in the military, the repeated leave-takings and trying to make new homes, and the glimpses of the variety of people and natural beauty in the nation. As the narrator enters her teens, there’s more sense of her looking for a place for herself beyond her strong family, and while the poet is tentative, as poets tend to be, we are sure she will make mark. In the last lines of the last sonnet, she closes a book, turns off her lamp, and speaks into the dark: Give me a message I can give to the world. The plea or prayer echoes a line from Emily Dickinson, who would become a cherished influence. Then the poem and book concludes with her “afraid there’s a poet behind my face.” Here’s the life: both the yearning and fear of hearing and being heard. I’ll be reading this thought-provoking and beautiful book again.

For the Poetry Friday roundup, please visit No Water River.

February 5, 2014

Safe Places for Dreaming, Reading, and Writing

In my children’s literature class, we left Fern sitting on a stool in the barn listening to Charlotte and other animals, but we’ll be reading about other quiet places – the Secret Garden, Terabitihia, Roxaboxen, and behind the couch in the Watson’s living room – where children go to find or recover their true selves, be it part of nature or a fire escape. So for this week’s writing assignment, while some students chose to write about the ways E.B. White brings out themes, others took the option of writing about childhood haunts or refuges.

Someone asked if it would be all right to just write about how and why a place was important, but not describe it. No, sorry, I replied. Grace Paley wrote that we write what we know to find out what we don’t know, and sensory details may not only lure in the reader, but surprise the writer. Uncovering one small thing may make forgotten parts appear, and the outside reveal what was forgotten within.

And I did feel a sense of discovery in short memoirs that introduced me to a forest hillside a student returned to and found to be really a rather few trees with beer cans and other litter on the ground near a busy street; still, he sat at the smaller crest of the hill and felt again like a king or warrior. I was happy to read about another’s window seat, bookshops, and the way in which someone was “almost raised by librarians.” At the school’s snack time, one shy boy started taking Goosebumps and other books to the quiet corner behind a seldom-used easel, then was pleased when another boy chose to join him. As weeks passed, other children came, too, and somehow there was room: he suspects the teacher quietly drew back the easel.

I read about a crabapple tree perch, pools that transformed swimmers into dolphins or mermaids, haystacks, a Crawfish Kingdom in a backyard brook, grandparents’ houses, a dance studio, a flowery cave made by a mother who planted morning glories over a bower, where tea for fairies was served on an old tablecloth, and an Electricity Shed Where You Shouldn’t Go Because It’s Dangerous, aka, The Headquarters, and more.

If we’re lucky or wise, we can call up a sense of being in those old cherished places when we need them. I spent much of this snowy day with a quilt drawn over my knees, watching the world turn whiter, while leaving it for a world I’m tucking between other covers. But sometimes we need a real place, either new to us or familiar, that gives us a sense that if we venture into the woods, a cottage with three plates and bowls set out, one just for us, will be waiting.

I hope my role running writing workshops at a spring retreat in northern California will help create such a safe place. At Candles in the Window: A Yoga and Writing Retreat (With Chocolate), we’ll get to look up at redwood trees, which I’ve never seen. But the notebook on my lap will be familiar. I’ll know at least one other person, and look forward to meeting people I expect will turn into friends. That’s the magic of safe places, sanctuaries, forts, or hideouts. Anything can happen.

Note; please click on the link above if you want to know more about the retreat held on the first weekend of June. There’s a discount for those who register before February 14.