If at First … Finding a Picture Book’s Right Title

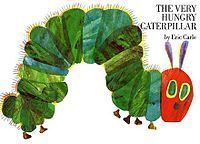

Titles can suggest the setting, a main character, a mood, or a theme, and with even some of that wanted in a few memorable words, authors may get them wrong at first. The Very Hungry Caterpillar gives us color, food, and an introduction to numbers, days of the week, and metamorphosis. We’d have missed much of that if Eric Carle’s editor, Anne Beneduce, hadn’t suggested he change his first idea, which was A Week with Willi Worm, thinking caterpillars are cuter. A good trade of alliteration for the chance of transformation.

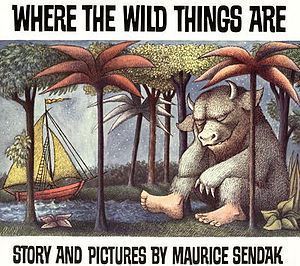

Where the Wild Things Are by Maurice Sendak began in 1955 as Where the Wild Horses Are, but his editor, Ursula Nordstrom, pointed out that he couldn’t draw horses particularly well. So he turned to Wild Things, with some inspiration from Brooklyn relatives who’d terrified him as a child. Still, much work was ahead until the 1963 publication of his classic. Maurice Sendak said, “I’ve never spent less than two years on the text of one of my picture books, even though each of them is approximately 380 words long.”

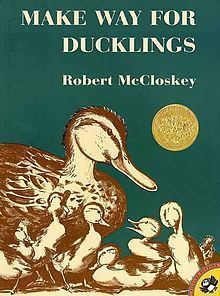

Robert McCloskey spent about a year to write the 1,152 words in Make Way for Ducklings and another year or two working on the drawings. In New York, he visited the Museum of Natural History, but also bought ducks at the farmer’s market, gave them a place in his bathtub, and followed them around his apartment with tissues. He held up the swaddled ducks to see what they looked like from beneath, and set out dishes of wine to slow them down enough to draw. His first title was Boston is Lovely in the Spring, but it seemed to occur to the assistant of his editor, May Massee, that neither the word lovely nor spring was as likely to grab a young reader a much as duckling, and a command has more energy than a statement. She came up with the title that suggests the connection between people and the duck family.

When Paris was invaded by Nazis in 1940, Margaret and H.A. Rey, who were German Jews, fled on bicycles with the precious few things they could carry, including several manuscripts, one of which was about a monkey. The couple made their way to New York, where editors admired the curious monkey, but weren’t keen on any species of boy named Fifi. His name, and the title, was changed to Curious George, though when published in Britain, it was changed again to Zozo, rather than possibly stir scandal by having a monkey bear the name of the king at the time.

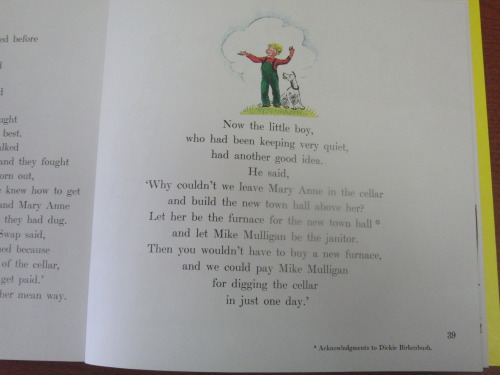

And not every editor will be one who sits behind a desk. Opinions may come from what some marketers call focus groups, but we might call story hour or the dinner table. Virginia Lee Burton, whose first book was turned down by thirteen publishers, was uncertain how to end Mike Mulligan and His Steam Shovel until a twelve year old family friend suggested the imaginative ending that the steam shovel Mary Anne, who had no logical way of digging herself out, become the happy furnace in the town hall basement. In the published book, a boy wearing green overalls comes up with the idea. It’s charming to see the asterisk and footnote: Acknowledgments to Dickie Birkenbush.

Much of what I know about the history of children’s books draws from the dedicated research and writing of Anita Silvey and Leonard Marcus. I thank them for their work which reminds me that it’s rarely if ever a short road to any book. Everyone needs time and help.