Jeannine Atkins's Blog, page 20

May 24, 2013

Tugs that Carry Writers Through

Even if we don’t make claims about fairy dust or lightning bolts, the word inspiration may conjure something swift, flashy, and strong enough to push us toward paper. My books have begun with some aha-moments, but ideas –small, vital, and unspectacular-looking as seeds — seem minor within the scale of the work. What matters more is whether my intrigue turns into a sense of responsibility, a term I’m using not with its sense of chore, but more like that of a parent who may rue sleepless nights, but delights in a small child’s goofy smile or fuzzy hair. The connection deepens as one question gets answered, while more come up. A scene or image seems to reflect another, toppling both into motion. That’s when I know I have a book.

But I don’t always get that complicated pleasure. Some months ago I’d set aside a novel I was working on to revise another. Now that I’ve finished that and hit a “send” button, I can return to my set-aside book. But it hasn’t been calling me these past weeks, and it didn’t hum when I picked it up. There’s no tug to keep me at my desk with a sense that this is a story to be written and I’m the one to do that.

My life has changed some since I began the novel, my interests shifted. I began wanting the challenge of writing something different for me, and attempted the sort of fantasy I admire in the course I teach. Tucking some magic amid scenes set in everyday places was a goal that also came from having had books in a form I thought I did best being turned down. I wanted to write something that might sell, which isn’t a bad thing, but it doesn’t mean I can count on a sense of personal connection between me and a subject. I missed that. As a friend pointed out yesterday, I spend a lot of time at my desk and it’s natural to want the people I find there to be welcoming. Karen said, “You don’t write magic because you find the ordinary world to be magical.”

Those kind words soothe my sense of letting go of about a hundred pages. I’m also comforted by having had a new tug enter my life this past week, a pull back to science, biography, and poetry, three words that won’t make many editors’ heart go pitter-pat. But it’s my own heart that keeps me alive.

Is a promise of connection between author and subject necessary for a good book? Do readers need to find traces of the creator in books or art, sometimes put in deliberately, sometimes not, but perhaps as inevitable as the shapes of sentences or the habitual angle and pressure of a painter’s brushstrokes? I don’t know, but I think it’s necessary for me. As I work on a good day (which still doesn’t mean it’s one without sighs and over-checking e-mail), the tug between me and my newborn creation fades in and out, but what’s lovely is when the tug eventually seems less from my side and more from words I set on my screen. Is this like a potter paying attention to the feel of clay under his hands, the force of a spin that his feet pumping the wheel have set in motion? Is it like a singer struggling to make her voice match the music she means it to be? Maybe some paintings aren’t complete until just the right trace of the artist’s eyes and hands blend with the subject. That sense of being with work that speaks to me as much as I speak to it may be the transformation William Butler Yeats imagined when he wrote “How can we know the dancer from the dance?”

For Poetry Friday posts please visit Jama, (where you’ll also find a recipe for delicious-looking mango bread).

May 18, 2013

Poetry Along the Way: Walking to Emily Dickinson’s Grave

The Emily Dickinson Museum sponsors an annual walk from the Homestead on Main Street in Amherst to a nearby cemetery to mark the poet’s death in May of 1886. This year I stood in the garden with about forty others, including five mother-daughter pairs, one dog named Phoebe, a young woman in a white dress (strapless), one man with a bunch of daisies, and one woman wearing a “I’m Nobody, Who are you?” t-shirt. Some read poems around the theme of house there, then we walked down a green path to Evergreens, the house next door where Emily’s beloved sister-in-law lived. I was among those who read there, Poem 1609, which begins, “Who has not found the Heaven – below –/ Will fail of it above –“ The microphones weren’t great, and we competed with noise from trucks, cars, and lawnmowers, but while it would be good to hear the poems from beginnings to ends, while breathing the scent of lilacs, picking up phrases was quite satisfactory. And noticing the effects of all those dashes read, or not-read, aloud.

More people read at the church across the street, which Emily Dickinson did not attend, it was pointed out, then between a gas station where her first home once stood and West Cemetery. Along our way we lost a few people and gained others.

We passed this mural, painted on the backs of shops. That’s the poet on the left, amid flowers. Another woman with a camera told me, “I didn’t know about this. Isn’t it great? And when I parked the meter already had two hours in it.”

Even those of us who paid full for parking were pretty happy, standing by the gravestone surrounded by buttercups, violets, and clover, with people taking out well-worn complete works of Dickinson, while the rest of us listened to more favorites. Pink or yellow lemonade was poured, so we all could toast Emily Dickinson.

I love this little box, held up, I believe, with baling twine, which contained folded poems and messages from well-wishers. We were invited back to the Homestead, which was open late that afternoon at no charge, but I headed to the library to pick up a few books, and write down a few phrases on their hopeful way to being poems.

May 17, 2013

Poems in the Greenhouse

Yesterday was the perfect day to smell lilacs and pass under the white blooms of dogwoods on my way to the Smith College Greenhouse. The museum area is currently devoted to a show called From Petals to Paper: Poetic Inspiration from Flowers.

Poems printed on placards and arranged according to flower types were selected by Liliana Farrel and Janna Scott, class of ’13, who were inspired by Annie Boutelle’s poetry workshop. Walls featured irises, tulips, and other spring flowers. The section on daffodils offered Wordsworth wandering lonely as a cloud, along with Robert Herrick, Amy Lowell, and Alicia Ostriker giving the flowers a political context. Poets including Li-Young, Mary Oliver, and Louise Gluck show flowers as solace, taunting, sensuous, exuberant, or demure.

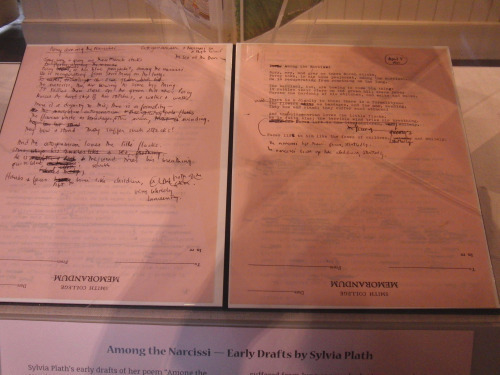

A small room was devoted to Smith alum, Sylvia Plath. We see a draft of Among the Narcissi filled with cross-outs and new words, with still more lines and notes from an editor at The New Yorker, then we see it published in the magazine.

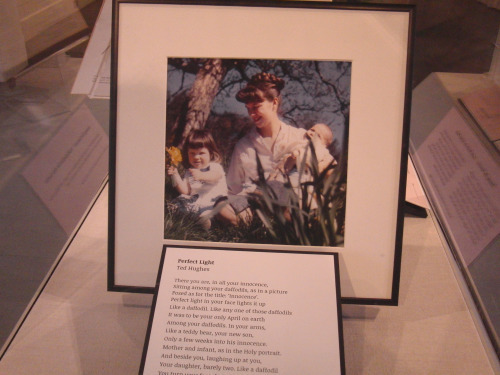

David Trinidad had given us a brief introduction to both Sylvia Plath and tulips in his amusing and profound poem The Red Parade. Here we find Sylvia Plath’s Tulips on the wall and can also listen to a recording on a television. The poem tells of a red gift in a stark hospital room at a time when the narrator felt as if of nurses were claiming her clothes, the anesthetist her history, and the surgeons her body, so that I believed the line near the end: “Tulips should be behind bars like dangerous animals.” I like the poem, but hope I just sound grateful and not smug when I say I’m glad I’m a person who can receive tulips and simply say “Thank you, what a gorgeous color!” The recording was made in 1961, two years before Plath would die by her own hand at age thirty, leaving two children.

This heart-tugging show is open until the first weekend of September.

For more Poetry Friday posts, please visit: Think Kid, Think.

May 10, 2013

A Way to Write a Poem about Science

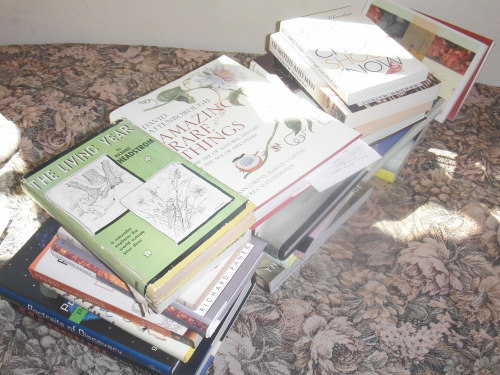

Read widely. Cut a path. Find poems in the sidetracks as I move in and out of my comfort zone.

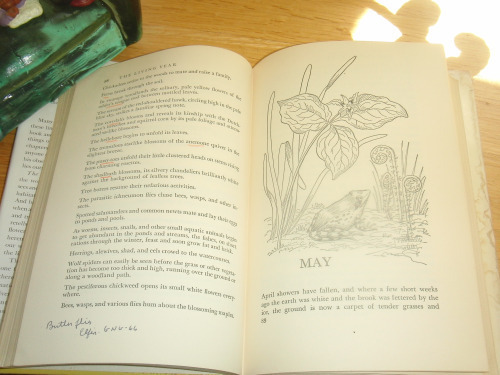

Look through a book from a long-dismantled shelf with my father’s penciled check marks besides plants he’d seen. Feel tender, which may suggest the shape and mood of a poem. Robert Frost said, “A poem begins with a lump in the throat.”

Dilly-dally. Focus. Take a break to read poems I like. Decide I want a bit of humor and kick up the rhythm and plot ways to end on rhymes. Or leave some in the middle of lines.

Pare down. Pat the dog. Pour more tea.

Come up with three or five poems. Decide on one for now. Write a lot. Choose eight lines. Fiddle with each one, trying to leave questions for readers to make each poem their own. Most images and ideas get deleted, but a few point ways to new poems or picture books. So it’s back to step one, with a new stack of books.

For more Poetry Friday posts, please visit Anastasia Suen’s Poetry Blog.

May 6, 2013

NE-SCBWI Spring Conference

I’m back from the spring conference organized by the fabulous volunteers of the New England Society of Book Writers and Illustrators. On Friday I gave a workshop called “Nests, Rooms, and Gardens: Using Setting to Structure Fiction,” and on Sunday I was part of a panel called “Sculpting Stories from Fact: Four Writers of Historical Fiction Share Strategies.” Pat Lowery Collins, Padma Venkatraman, Sarah Lamstein, and I talked about inspiration, ways to decide on the right details and how we let precious ones go, the role of visiting sites, how we make choices when history and demands of story seem to clash, and other issues.

Jo Knowles accepted the Crystal Kite Award for her novel, PEARL, and spoke of the ten years of writing before her first manuscript was accepted, and how important friends and colleagues were to her to keep her faith. You can read her touching acceptance speech here.

Grace Lin gave an inspiring keynote speech, talking about her childhood love of princesses, princes, and fairy tales, but how over time she came to see her family and their culture as more important, and wanted to use the color and patterns she found in Chinese art in her work. Instead of sidling away from the term multicultural as some advised her would be best to advance her career, she embraced it, and found a devoted audience that only became bigger when her novel, WHERE THE MOUNTAIN MEETS THE MOON, won a Newbury Honor. And as you can see, she is the mom of a most adorable baby.

Linda Urban gave two workshops. I was happy to get to her one on The Power of Point of View, which was packed with information about not only the subject but so much more, as changing point of view changes everything.

It was good to chat with friends including Lesléa Newman, who spoke about “The Gender Dance: Picture Books That Challenge Stereotypes” and Lisa Papademetriou, who explained The Art of the Outline.

At the end of the conference, as I entered the room where we were to sign books, other authors had longer lines in front of their tables, but before mine bounced the only person wearing a bathing suit, as well as glittery flip-flops that matched her cap. This was a conference for working adults, but this girl, her mom, and grandmother were hotel guests who’d passed the bookstore, found and bought GET SET! SWIM! and taken some time off from an afternoon at the pool to have me sign the book I’m happy Lee and Low has kept in print for many years. Some books find their perfect reader.

Throughout the weekend I heard much good advice about theme, characterization, and structure, but here was inspiration in a beautifully chlorine-scented incarnation. Girls like this one, and curious-about-the-world babies like Grace’s, make me want to write.

May 1, 2013

Novels That Move Between the Present and the Past

Three recently published novels keep some chapters in the present, then switch the point of view to explore characters who lived in the past. MARY COIN by Marissa Silver examines the ways art, language, love, and fear shape memory. Art and legacy are also themes in THE HOUSE GIRL by Tara Conklin, which considers a broader sense of our country’s past and the ways we balance pride and guilt. THE OBITUARY WRITER by Ann Hood is about the way losses and yearning shape two lives, with the two settings about forty years apart dropping into the background.

The three main characters in MARY COIN are a historian whose heart beats hard at the sight of stacks of old letters or even financial records, a photographer whose work begins as a way to earn a living, then turns into art, and a migrant worker who tends to her husband and children with exquisite care. Reading along, I only gradually had a sense of how the three strands might intersect, but I never doubted that they would. This book has sentences that made me stop and marvel. Here and there, entire life histories seemed contained within a page.

The photographer finding her subject takes up themes of who we are, where we belong, and what can or can’t be found in a portrait. While we may initially ache at the evidence of hardships we see in the photograph of the woman here called Mary Coin, inspired by a photograph by Dorothea Lange, we get to see her dancing with her husband, for instance, in a small room surrounded by hungry children, who are struck wide-eyed and silent by their parents’ love. Themes of history are developed through the professor whose story begins and ends the novel, and also in scenes like one in which we watch Mary’s grown daughter help clean her trailer toward the end of the book, taking out an old hat that makes Mary remember the complex desires of her own mother, and how these got hidden. These are erased again, at least for the moment, as Mary waves her hand and says only, “Give it away.”

The novel’s three strands wind into a loose knot suggesting that so much of what becomes history is happenstance, and like life, is beautifully elusive. In a different way, THE HOUSE GIRL by Tara Conklin, with one part told in 1852, and the other in the present, considers what we take from the past. What goes missing? What can inspire? What must be forgiven? What memories, conversations, letters, pictures do we keep and what will slip away?

This novel begins with the line: “Mister hit Josephine with the palm of his hand across her left cheek and it was then she knew she would run.” Right then and there I was on her side, while when in the second chapter we’re taken from 1852 to the present, I felt at first resistant, for Lina didn’t capture my attention in the same immediate way. How could she? The voice telling Josephine’s story is urgent, and we get smells of moss, tobacco, collards or oil paint in steamy heat, and a tone that’s both gritty and languorous. Lina’s world is often climate-controlled, her time in the law firm clocked to the minute, which increasingly bothers her. As she faces her own losses and finds her own courage, the stories came together. More voices are added by letters written during Josephine’s time that Lina reads for a reparations suit in which she considers paintings that might have been painted by Josephine and not credited. Toward the end of the novel, these letters connect the two lives and time periods more deeply. Like the book’s first sentence, the last one is astonishing, but I won’t disclose it. The book both felt complete and made me wish to pick up another book devoted to these lives.

Reading Ann Hood’s novels or nonfiction is like eating your favorite bread with your favorite jam. Maybe there’s rain tapping the windowpanes, and your tea is still hot. THE OBITUARY WRITER is a departure from her usual contemporary settings, but both the goodness of her style and themes of loss remain, the assurance that we’ll be taken through common details or somewhat ordinary people into heart-rending places. Ann Hood has a gift like Jane Austen, and the best gossips, of being able to point out oddities and foibles in a loving way. In the opening of the novel, a child disappears from a suburban street, which doesn’t strike us as entirely harrowing, for the focus is on the reactions of neighbors who arrive at the house armed with casseroles and cakes, as if shields against fate, and comment that it seems the mother of the lost child could have washed her hair at least when she knew a TV cameraman was coming. The loss is an impetus for a central character in an unhappy marriage to instigate an affair. This isn’t the first or last time I read with thoughts that rolled like waves, one after another, “Really?” and “Of course.” We’re invited to smile at human folly both in this early 1960’s setting and in alternating chapters set in 1919 about the gifted obituary writer and her lost dream, which are woven together with a similar style built from a keen eye for detail.

April 29, 2013

The Empty Briefcase

Daffodils, magnolias, and cherry trees were blooming in Amherst as I walked to the Institute for Holocaust, Genocide, and Memory Studies. I put those yellow and pink blossoms at the beginning of my sentence, and I’ll add that a kind person had set out a plate of brownies, so you’ll know that hearing my student defend her thesis on the Holocaust in Literature for Children and Young Adults was a happy occasion, despite subject matter it hurts to think about. Tylar Suckau answered questions about work by Elie Wiesel, Jane Yolen, Art Speigelman, and others who wrote directly or indirectly about the death camps, and the various powers of fiction and nonfiction, and the ways lines blur between them.

As we settled in a room, I asked Professor James Young about a briefcase that was propped beside books in a glass case. He told me that the Institute had been given some papers from the Nuremberg trials, and the worn leather briefcase had belonged to a lawyer. Among the contents was a letter that began with the admission of responsibility for the deaths of about 1400 people, and ended with a plea that he was basically a good man, who was kind to animals.

Would I have noticed the briefcase if it were not behind glass, or even if it had been labeled? The display case gave it importance, while a little sign might have suggested the end of a conversation rather than starting one. An object in a case suggests that someone saw something worth saving. People change their minds about what matters most and what can or should be forgotten, but I’m glad that when historians sort, they preserve some ordinary old things that may provoke curiosity, perhaps especially when seen out of their usual context. I’m not planning to write about the Holocaust, but if I were to research the names of people and places, or theories on genocide, when feeling overwhelmed I might remind myself to return to that old briefcase, which made my heart thump. I’m sorry I didn’t take a picture, but here is the building that houses it.

Both a writer’s engagement and a reader’s belief often begin with artifacts. Tylar mentioned how crucial it seemed that Art Spiegelman included photographs of his parents within the drawings of his graphic novel, MAUS: A SURVIVOR’S TALE, as a record of a moment when fact merges with fiction, and personal into more generalized history. What she calls paratexts and I more often call the afterword or the stuff at the back of the book, are also fairly ubiquitous, often as a way to suggest the context or point readers to the vastness beyond this story. Sometimes an author’s method is described. At the end of NUMBER THE STARS, Lois Lowry shares her factual inspiration, including a friend upon which she based the main character, how she walked the cobblestone streets in Copenhagen where her characters walked, considered a photograph of a face so young it broke her heart, and used a hand-hemmed linen handkerchief, taken straight from history, as a major plot point.

In a discussion of how the Holocaust may best be presented to children, naturally we considered the ways authors balance a terrible reality and hope, how lines were kept or crossed between truth and evasion, depictions of evil and sentimentality. Just as many caregivers today put on emphasis on rescuers and others who do good even during times of horror, most of the earliest introductions to the subject feature people who saved lives. I NEVER SAW ANOTHER BUTTERFLY introduces young readers to concentration camps by showcasing the poetry and paintings of children, few of whom survived imprisonment at Terezin. These were less often pictures of barbed wire and more often of dandelions painted on scraps of informational paper. James Young pointed out that thinking about better days was sustaining, with Primo Levi reciting Dante from memory, and singing, and talk and thoughts of past warmth and beauty. When we confront pictures of the death camps, it’s important to remember that we don’t see everything.

There’s often some part of us that doesn’t want to see the worst, or which we let ourselves glimpse only from the edges. I was horrified to read the letter that had been in the briefcase, written by the man who was good to animals — not that he shouldn’t be, but I was stunned that he thought it right to include that in his admission of killing innocents. I can’t understand, but that small window of his letter gives me some insight into a time and place that is in many ways incomprehensible. I’m glad that historians do so much more than tally losses, but continually uncover and rescue, sometimes one briefcase at a time.

We congratulated Tylar on her thorough study and her graduation, then passed through the kitchen on the way out. A string from an overhead light brushed my head. The linoleum and speckled Formica evoked the 1950s, closer to the time of what’s studied here, back when classes on the Holocaust didn’t exist, and this building was used for something else. Which would be another story.

April 26, 2013

Historical Portraits

I’ve been writing a novel based on a woman from history who’s known, but not as much as I think as she deserves. I have my own answers to the question of why and how one would one turn a real life not into fiction rather than biography, but I’m always interested in other approaches. Three books published within the past year suggest different possibilities of ways people might be remembered.

FEVER Mary Beth Keane is an imagined recounting of Mary Mallon, who came down in history as Typhoid Mary, the first person in the United States believed to be a carrier with no symptoms. I love the first line: “The day began with sour milk and got worse.” We read of the general sense of loneliness any outcast might feel, underscored by Mary’s particular tenderness, and get harrowing descriptions of how this fever took hold. As Mary moves from kitchen to kitchen in search of new jobs as cook, we’re shown how some servants help each other out within the upstairs-downstairs of grand houses, or view one another as competitors.

Mary Beth Keane’s list of sources is fairly spare, suggesting that much of her obviously extensive research was done on New York and its immigrant population in the early twentieth century rather than biographical material on Mary Mallon, who was developed through a novelist’s queries. She’s shown as sometimes sensitive and sometimes a spitfire, often generally oblivious, as we all are sometimes, blocking evidence of what we don’t want to see.

The life of Zelda Fitzgerald — debutante, dancer, painter, writer, and wife of F. Scott Fitzgerald — has been long documented by herself and others. She was famous in her time for her wit, beauty, stays in mental institutions, and accusations of being destructive to her husband’s career, sometimes in almost the same breath as she was called an asset. Who was she? We can’t really know, but in Z: A NOVEL OF ZELDA FITZGERALD, author Therese Anne Fowler takes a well-informed and imaginative stab at an answer. Lots of journals, letters, reportage, photographs, and the subject’s own stories and paintings were available, so well-informed, Therese Anne Fowler structured the book partly around some of the hidden motivations within any life. She writes in the afterword of the many myths that were passed down, and took it as her job to look for truths and motivations behind them. For instance, she knew that Zelda and Ernest Hemingway did not get along, and wrote to discover an answer as to why, which appears toward the novel’s send.

Jennie Fields wrote THE AGE OF DESIRE, a title which is a play on that of Edith Wharton’s THE AGE OF INNOCENCE. The voice that Jennie Fields created, sometimes sensitive, sometimes assured, fit what I imagined Edith Wharton’s voice to be. The novel’s texture is thickened by being told alternately from her point of view and that of Anna Bahlmann, who was first Edith’s governess, then became her secretary and a friend who knew her perhaps better than anyone. The time period focuses on the years when Edith was in her forties, with the plot taking shape around Edith’s affair with journalist, Morton Fullerton. The points of view of the two women show the tensions between rapture, guilt, hope, fears, and hiding. I was pulled in!

As with the case of Zelda Fitzgerald, Jennie Fields had extensive biographical material to draw from, including many newly found letters, and she notes that she often began her daily writing by reading a few pages of Edith Wharton’s exquisite prose. And her study showed. I felt as if I understood parts of Wharton that I hadn’t understood before. And this novel, like the others, widened my sense of the lives of women from the past.

April 24, 2013

Historical Fiction

I’m speaking on a panel called “Sculpting Stories from Fact: Four Writers of Historical Fiction Share Strategies” on May 5 at the NE-SCBWI conference. What a treat to speak with three smart friends — Sarah Lamstein, Pat Lowery Collins, and Padma Venkatraman – who have written about a 1950’s childhood (and whether or not you lived through that decade, we’re calling it history now), Venice in the 1700’s, and India at the time of World War II, among other subjects. As I consider the hows and whys of delving into the past, I’ve been immersing myself in historical fiction and thinking about the purposes of each novel, which not only depict different times and places, but suggest different answers to why the author chose to set the work in a particular era.

A crisis in CASCADE by Maryanne O’Hara is based on a historic event in Massachusetts, when towns were flooded to make a reservoir to supply water to Boston. The threat of rising water and drowning is used as both plot element and metaphor. Desdemona, named by her theater-loving father, reacts to pulls of love, money, power, and other events that seem beyond her control, while keeping some sense of stability by painting. I loved a scene in which she breaks lots of eggs to make tempera paint, and her sense of her own recklessness is underscored by this taking place in the Depression. How many breakfasts would be missed because she wanted to paint? I also liked learning about the role of government support of art during the New Deal, which made me think about ways art is important, and supported or not, in the lives of people I know now.

THE POSTMISTRESS by Sarah Blake came out a few years back to both acclaim and good sales, but though I’ve been advised as often as anyone not to judge a book by its cover, that wrinkled purple rose suggested to me something more romantic than what I cared to read. There is love in the novel, but not of the beyond-belief variety, and the effects of war on three strong women are prominent as their lives are gradually laced together. The setting is integral for many reasons. One character is loosely based on Martha Gellhorn, and we learn about foreign correspondents during the war and the role of communication gone astray. This theme is echoed in a missing letter, which, like a missed phone call, is unlikely to cause a crisis in our times: one can so much more easily try again. The ante is also up because the missing mail is no accident: the postmistress chooses not to deliver the letter. In the afterward, Sarah Blake explains that she conceived the novel after the September 11 attacks, trying to understand the ways that public and private grief and fears intersect, as so many people experience during a war.

“Used to be when a bird flew into a window, Milly and Twiss got a visit.” From that first sentence, I thought I’d be happy to know the two elderly sisters in Rebecca Rasmussen’s THE BIRD SISTERS rather than being sent back decades in the second chapter. But the games of Truth or Consequence, the yellow cakes, and shell-shaped soap all came together as a man with a box of framing nails and tin of black licorice escorted Milly from the general store to her car, where Twiss was reading the Farmer’s Almanac and drinking a cream soda. Love and sacrifice come together in a way that might be most believable in1947, and along the way we’re treated to moments of beauty and humor such as when Twiss asks a teacher about women during the Revolution, and is told that Betsy Ross sewed a nice flag. The novel examines happiness from more than the birds, who are often a symbol, but who the sisters well know have fleeting lives. In the first chapter, they run out of their mother’s old handkerchiefs that they used for burials of birds they couldn’t save.

A long ago sentence spoken to a boy who mows the lawn can change a life as definitively as a photographer chooses what will go in or outside a frame, a reference to the imagery in another wonderful novel, Marissa Silver’s MARY COIN, which I’ll write about next week, along some other novels that cross between scenes in both the present and the past. And I’d love to know the titles of some of your favorite historical novels!

April 23, 2013

Writing Poetry Together: Mothers and Daughters … or Variations Welcome!

Let me know if you want more information! This will be fun, and it’s free! Thank you, beautiful Lilly Library!