Jeannine Atkins's Blog, page 12

March 23, 2015

Amsterdam Treasures

The tulips weren’t yet out when my daughter and I vacationed in Amsterdam last week, but we saw crocuses starting to turn lawns purple and daffodils in sunny spots of the park. We spent a lot of time in museums. In The Rijksmuseum, Rembrandt’s “The Night Watch” commands a wall, and was still surrounded by its usual crowd.

We got a better view of the also impressive “Anatomy Lesson” in the Mauritshuis, which is about an hour train ride away in The Hague. (And also saw Vermeer’s “The Girl with Pearl Earring.”) Rembrandt painted this when he was twenty-five, yet his overspending meant that he died penniless. Historians used the list of items taken from his home to pay off debts was used to furnish the fascinating house where he lived, painted, and sold work for twenty years.

Loss is part of history. I loved how the Van Gogh Museum is entirely devoted to the work of one man and his friends. Self portraits are lined along one long wall. Upstairs, we moved through halls of showing his start as an artist painting dark fields and workers, admiring Millet, then moving along to bright scenes painted in southern France, some from an asylum. Vincent Van Gogh died in a possible suicide (which recent biographers call into question) north of Paris. Like Rembrandt, he died in debt, but he didn’t have the earlier artist’s reputation. Wondering how about 200 paintings came to be in Amsterdam, I’m now reading and learning about the years following his life, when the Rijksmuseum refused to show his work, finding it unsuitable to be hung near Rembrandt, Rubens, and Frans Hals.

While Emily and I marveled at the art, (and she took the pictures, while I focused on staying out of the way of pedestrians and bicycles) she asked me about Dutch writers. I couldn’t think of any except Anne Frank, who was in Amsterdam in hiding, her plaid diary kept by one of the people who tried to save the family from the Nazis. That diary was seen into publication by her father, the one surviving member of the family. It seems Otto also oversaw the annex restored as the Anne Frank House. He wanted the rooms to be left stripped, as the Nazis left them after taking or wrecking furniture and things. It was a moving choice (as well as practical; the place is crowded.) In Anne’s room we see, now under plexiglass, clipped pictures of things she loved: film stars, pretty children, royalty, and art. Some are torn, suggesting, like a diary, what is left out. She would likely have grown into a still more amazing writer, but it’s her ordinary and beautiful hopes and the ruthless assault upon them that is moving here.

Emily and I left the city for part of a day to see and hear the soft whirr of windmills in Zaanse Schans. Lovely how they keep spinning, like history, moving with what’s kept and what’s lost, what is left to see and important gaps, too.

March 10, 2015

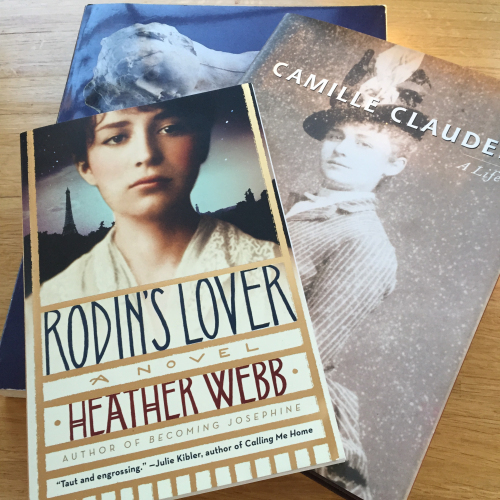

Women Artists in Fiction: Rodin’s Lover by Heather Webb

Many who’ve seen the rough, fluid lines of Rodin’s stone or bronze figures are convinced of his passion. Many get the same impression from the sculpture of the lesser-known Camille Claudel, who often worked on a smaller scale. At eighteen, she became Rodin’s student and one of his helpers: carrying buckets of water, kneading clay, and sweeping plaster dust. Like many talented students, she taught her instructor, too, as Heather Webb shows in her moving novel, Rodin’s Lover.

As the title suggests, there’s a focus on the heat between them, but we also see friendships, Camille’s relationship with her parents and brother, and the joy she finds working with her hands. One scene shows her selecting the first stone she carved, chiseling the alabaster into “Slender fingers laced together as if uncertain whether or not they would poise for prayer.” The amount of time and thought behind sculptures that might look quickly done is well conveyed. We see not only artists in their studios but dealing with business: going after commissions, courting patrons, looking straight on at compromise, and coping with competition. Camille had the additional work of proving herself in a male-dominated field. It was hard enough for a woman to paint in the 1800s, but still fewer found ways to make careers as sculptors. Whether in stone or bronze, it’s messy, expensive, and takes up space, asking for something beyond a wall.

The novel is mostly told from her point of view, but sometimes switches to Rodin’s, who’s often showed as vulnerable, even shy, in contrast to Camille’s self possession. I loved her confidence, though it was tragic when illness made cracks through that, in what Heather Webb shows, with plenty of historical evidence, as schizophrenia. The diagnosis isn’t announced, as it wouldn’t come into Camille’s mind or ours as we stay in her point of view. The first voice she hears is a warning to stay away from Rodin, advice which she’s already heard from her friend Jessie Lipscomb and herself. Other voices develop from her (well founded) fear of betrayal and competitors, blossoming into paranoia. Some of her strong responses to people are like her mother’s, so she wonders if she’s simply and sadly becoming more like her. The onset of a terrible illness is not one downward sweep, but, like many illnesses, full of mystery as it comes and goes and is interspersed with days of love and work.

It was good to spend a few days of this too-white winter in Paris, working, though the novel does take us into a few dance halls and to tables with absinthe, talking about art.

March 5, 2015

Looking Out, Looking In

“Maybe the surest way to know the self is not through looking in the mirror but going out for a walk.” – Mark Doty

I’ve been thinking about what is the poetry beyond the broken lines in verse novels. I love the muscle of narrative’s bright beginning, the arc to a climax, and reconciliation or fresh questions at the end. There’s something great about the shape of a beginning, middle, and end, going from A up to B and back down to C. In Aspects of the Novel, E.M. Forester distinguishes between story, giving the example of “the king died” and plot, which deepens and complicates into “the king died of grief.” Now there’s cause and effect, and emotion. It’s that element of feeling, which may be called lyric, which may bring the verse into narrative verse.

Of course feelings don’t mean gushing. Instead, it’s good to be on the lookout for the telling details that will lead to an inner life. One of poetry’s subversive powers is to ask us to slow down. I set my characters strolling, long looking, and perhaps finding a way inside.

March 2, 2015

Semi-Real Lives in Selma, The Imitation Game, and Mr. Turner

I’ve recently seen movies based on the lives of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., mathematician Alan Turning, and painter J. M. W. Turner. All have stirred discussion about the ways fact merges or clashes with fiction. In Selma, director Ava DuVernay and writer Paul Webb moved beyond some of Dr. King’s most famous actions and speeches to show a vision of part of a city and how many people came together to create change. We sometimes get heart-breaking intimacy, such as the glimpse of girls talking about hair and hats just before becoming victims of a church bombing. Sometimes the camera makes a large sweep over crowds to suggest the scale of the movement. Conversations between Dr. King and President Johnson have been criticized for not giving the president his due. In terms of story, a foil was needed, and I personally don’t think the president came off as villainous. Some facts may have been tipped, but what led up to a famous march from Selma to Birmingham gave me what felt like a true enough sense of history.

I also liked The Imitation Game, which was based on the life of Alan Tuning, someone I’d never heard of before. A core idea is that it took someone with secrets to uncover secrets. In the movie Alan Turing hides from most that he is gay. He nearly single-handedly shortens World War II by building a complicated machine that decoded German messages. An important young friend tells him, “Sometimes it’s the people who no one imagines anything of who do the things that no one can imagine.” Alan Turing repeats this to a woman he hires to help, and just when he needs to hear this again, she offers it for a third time. A bit hokey, but terribly moving, the way good movies can be.

How much of this was true? I read Christian Caryl’s article in the New York Review of Books that draws from two biographies to document how Turing wasn’t as geeky, unpopular, closeted, or alone as depicted. Of course the decoding was far more complicated than is shown. The manner of Turing’s death may not have happened as shown. I was interested to learn these things, but I was glad that some Hollywood turns and Benedict Cumberbatch pulled me into the story. The article ended with the suggestion that we might go to the biographies, but that those who wanted to see a rich depiction of another great British man should see Mr. Turner. I didn’t need urging, as I loved the trailer I’d seen in December.

But the movie? No. I liked the scenes of Turner painting landscapes, but nothing else. I wasn’t expecting much plot, but was writer and director Mike Leigh trying so hard to stick to life that he took few risks to get under the artist’s skin? I lost patience with the way people came and went and were never seen again. Little was offered to connect us to scientist Mary Somerville, critic John Ruskin, painter John Constable, or Turner. I could put up with some grunting taking place of conversation, but expected more coherent words between. The movie took almost two and a half hours to get to Turner’s death and my favorite line, “The sun is God,” which I remembered being reported to have been his last words. We can glimpse spirituality in his paintings, but not the man in the movie. The final scenes showed Mrs. Booth, a woman who shared her house with him for years until his death, forcing a wobbly smile as she scrubbed the windows. Then we see Turner’s maid, whom he treated abysmally, looking lost as she tidied up paints. Were these forms of grief true to life I wondered as the credits began to roll. With little to grip me, and much to repulse, I’d been wondering all the way through.

Some people may leave a movie based on real people and events feeling betrayed if what they see seems too far from history. But we can also feel betrayed by a lack of story, an engaging beginning, middle and end. We expect the people we meet on the screen to matter to the whole, rather than wander through as some may do in life. We expect a vision that might even go beyond what the person at the center of the story could see. I’d rather have a few cords pulled behind the curtains to rearrange time, a wide brush that colors shades of good and bad, with some subtlety. Truth, yes, but feel free to mix with imagination. Please give me a movie that makes me care.

February 24, 2015

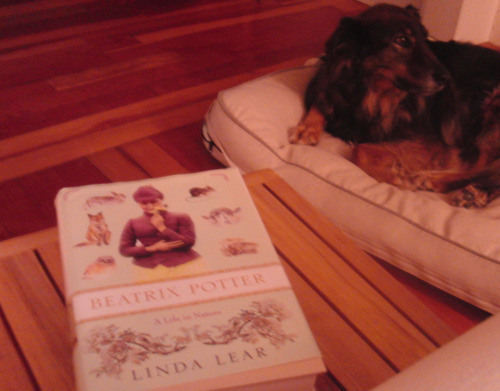

Beatrix Potter: A Life in Nature

This snowy month is a good one for slim books of poems and thick biographies. Because I often read history and biographies for research, I don’t always make time to reach for them for pleasure reading. This meant a thoughtful gift from my husband, Linda Lear’s Beatrix Potter: A Life in Nature, a gorgeous, carefully written, but undoubtedly hefty volume has been on hold for a time when I could immerse myself in this life. From the first page, I was swept in as Linda Lear began with references to Beatrix Potter’s work as an artist and writer, while showing her on the land she bought at mid-life when her career was established. The farm in England’s Lake District satisfied her love of the pastoral and mystery, while also giving her the routines of farming life and a sense of permanence.

Linda Lear shows us Beatrix’s childhood and the third floor nursery, with its menagerie including rabbits, frogs, mice, bats, snails, and a hedgehog or two. She shows the love she had for her younger brother, the guidance her father, an avid photographer, gave to vision, and a relationship with her mother that couldn’t be called tender. But she breaks the myths of bars on the nursery windows, and while not suggesting that Beatrix’s mother was an ideal one, she generously and astutely reminds us that her pretentions might well have come from the powerlessness she found as a woman in upper class Victorian society.

Beatrix always loved stories, and the fairy tales told by her Scottish nanny seemed as pivotal to her as those C.S. Lewis’s Irish nanny told him: bringing enchanted forests and winged creatures to stave loneliness. Beatrix read Edward Lear’s nonsense verse when she was four and Alice in Wonderland when she was six or seven, and began doing her own illustrations for these works. Linda Lear notes that later she’d enjoy and find creative inspiration writing letters to children just as Edward Lear and Lewis Carroll did.

Beatrix also enjoyed reading what she’d later call “good-goody, powder-in-the-jam books.” But perhaps, at age eight or nine, she found more of herself while drawing rabbits in jackets and scarves ice skating and such. Later she had art lessons, and her father’s friend John Millais gave her instructions and advice on painting. She was drawn to watercolors and felt she learned most from visiting galleries. Turner was her favorite, though she was interested in the work of women such as Angelica Kauffman and Rosa Bonheur.

Beatrix studied ferns and fungi, painting these close-up as well as landscapes. She became an accomplished amateur scientist, writing papers and setting forth theories, though her gender excluded her from some scientific circles. We get the particulars of this work and how she came to write, illustrate, publish, and market small books for small hands. Linda Lear paints a less romanticized version than we’ve seen before of the two important men in her adult life, but says she fell in love “slowly and companionably” with both and was “lucky in love, particularly for a woman of her class and era. The book ends with Beatrix bequeathing land to the National Trust “at a time when the plunder of nature was more popular than its preservation.”

Beatrix loved fairy stories as a child and surely never entirely lost her attraction to the fanciful, but in her last years she was most known as a good friend to many, a clear-headed sheep farmer, a happy wife, a grand protector of the land, and someone who valued simplicity, no nonsense. Lear quotes the death notice in the local paper that has no mention of the work which made her famous, and ends with “No mourning, no flowers, and no letters, please.” Beatrix’s ashes were scattered in her beloved hills, though exactly where has remained secret, as she wanted.

It’s all exquisitely told and researched (with almost 100 pages of notes!), as is Lear’s prize-winning Rachel Carson: Witness for Nature This is a big book, but now that I’ve finished I am miss Beatrix. Maybe I’ll pick up one her small books.

February 17, 2015

Remembering Maxine Kumin

Maxine Kumin’s life and poems keep inspiring a year after her death, her ashes scattered in the outermost pasture between the vegetable garden and the woods of her southern New Hampshire farm. The January/February issue of American Poetry Review includes “Maxine Kumin’s Legacy: Six Voices,” deeply moving tributes from poets who adored her, some first as students, and later friends who’d visit and talk about poems by the pond, ride horses, or cross country ski. All six poets are women, and several spoke of her importance to them in showing what a woman poet could be: deeply engaged with politics, physically strong, happily married, a good mother, a nurturer of animals, a generous and intelligent teacher, and committed to her writing. Her example was a welcome relief from more publicized images of women poets as solitary, suicidal, or narcissistic. Emily Grosholz writes of how Maxine “just wanted to write poems and ride horses and raise children and run a farm and respond to her friends and tell the truth about the world as she understood it and generally get on with her life.”

Robin Becker remembers how Maxie showed up in her graduate class at Boston University in 1973 as a substitute for Anne Sexton. Robin was a closeted lesbian at the time and had turned in a poem with pronouns carefully deleted. She writes that after her peers respectfully commented, Maxine noted, “We don’t know if this poem’s about two women or two men or a man and a man and a woman.” Robin asked, “Does it matter?” “It matters if you want it to matter,” she replied.

At that time Robin was trying to figure out what mattered, and as she did (“what matters to me resides in careful looking”), the two became friends, over the decades exchanging poems, with Maxine offering “hardnosed but encouraging, critical commentary” and talking about their work as teachers.

Deborah Brown writes of Maxine’s resistance to abstractions, and Darla Himeles quotes, “A poem is built on the furniture that’s in it,” referring to “the nouns and verbs that form a poem’s internal structure – key words that should be sturdy, aesthetically appropriate, and specific enough to be poetically functional.” She also quotes her from a workshop at the Provincetown Fine Arts Work Center as saying, “A poem is a small thing. It’s fragile, and you don’t want to overcrowd it.”

Carole Simmons Oles remembers making lentil soup she brought to Maxine’s house after her good friend Anne Sexton died, then forty years later, simmering it in her kitchen after receiving “the news from Maxine’s daughter Judith that her mother was slipping away.” Carole wrote about their early friendship and the later years when Maxine struggled with pain and health, sustained by writing. These pages are filled with grateful lives touched and changed – so grab this issue of APR while you can. The tribute ends with Alicia Ostriker’s poem, “The Redeemed World,” that cites strawberries, horses, the pond, the Red Sox, and Maxine’s love and courage.

February 13, 2015

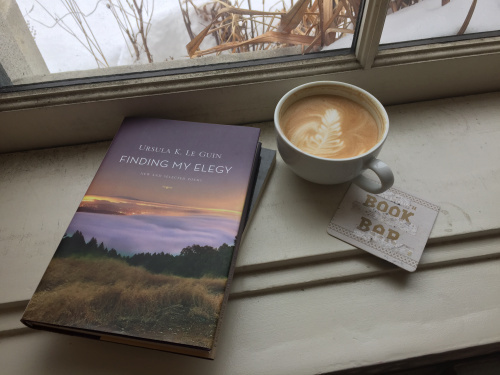

February Excursion

Even we who love snow are kind of sick of it, and I expect those who don’t live in New England are tired of hearing us protest that really there has been a lot. Yesterday I drove into Portsmouth where I had to vault snow berms to feed the meter, then walked among others sheltering our achy-from-shoveling shoulders, eyes aimed at the slippery sidewalk. We were overdressed and underclean: salt-stained jackets, slush on our boots. (Of course I mean overdressed in the sense of bulk, not fashion – there is none.) Many mouths were pursed, foreheads furrowed. Or was that just me? My kind friend Amy sent me a photo she took of an eagle overlooking a frozen river, and I wrote back that her eagle looked disgusted. Oh, no, she wrote, he is thinking, “Isn’t this lovely.” Some of us manage better than others.

Yet people on the whole are kind to each other, showing patience at corners with vision blocked by towering snow banks and give a brisk New England wave to thank those who pull over for safety. Lost mittens are posted on picket fences. We have weather conversation and sympathy at the ready.

I went to Riverrun Bookstore, where I was greeted by a display of books on Shackleton and his collapsed and frozen ship. I bought a copy of Megan Mayhew Bergman’s Almost Famous Women and The Fo’c’sle a gorgeous picture book written and illustrated by Nan Parson Rossiter based on Henry Beston’s The Outermost House, which I decided to reread, though should I begin with winter or summer by the ocean? Then I made my slippery way over to Book and Bar, quiet that morning, so I got a great seat by the window and in the shadow of their great poetry selection. I wrote about two sisters, a boy, a dog, chickens, and summer, taking breaks to read poems in Finding my Elegy by Ursula K. Le Guin. I hadn’t known she started out as a poet. This collection holds 70 selected poems from the past and 77 new, often about mythology or cosmology, artists or explorers, cats or lions, nature, aging, elusive knowledge, and shifting gifts.

I drove back home with new books and new chicken-filled pages through fluffy falling flakes. I walked my dog down the quiet road until we were met by a golden retriever with cabin fever. I unleashed Parker and a woman and I watched the dogs and her two-year-old bound around them. The boy shouted gleefully, waving bare hands, with his mom explaining how he hated mittens. Snow fell on our little crowd without shovels, leashes, or child-sized mittens. Then the laughter of the boy with small red hands swerved to wails as he realized that while the world is beautiful he was cold. His mom scooped him up, the dogs ran one last snow-spraying loop, and we headed our separate ways to warm houses.

February 12, 2015

What I’m Reading: Breathless and Gorgeous Infidelities

Two new poetry collections from friends have brightened my winter. The themes of family and time bind the poems in Sarah Lamstein’s Breathless, available from Finishing Line Press. References to rites and rituals take place beside ordinary family moments in kitchens, yards, or bedrooms. With the first poem titled “Pregnant” and that last one “Old Man Catching His Breath,” a loose line weaves generations considered with honor, humor, and awe. In “Last Moments,” Sarah compares the way a mother watches her young children to sitting with someone dying, “keyed to every sound and movement/ trying to ease their passage.” Her language is precise, and her vision makes the world seem larger and full of joy.

Gorgeous Infidelities is beautifully printed and bound with marble-papered covers, suitable for an artistic collaboration. The poems were written by Naila Moreira and the black and white photographs, mostly of people, landscapes, and interiors, were taken by Paul Ickovic. The poems are in a sort of loose dialogue with the photographs; sometimes I’d find a link, sometimes not, but there was never a sense of direct illustration and both works were complete in themselves. Many poems are built on the forces of love, curiosity and yearning and bring in science – particularly botany and astronomy – politics, religion, and nursery rhymes. The gifts of chance encounters seem to link the poems and pictures in this signed, limited edition that’s available at Broadside Bookshop.

It was a pleasure to read poetry by writers known more for their prose. Thank you Sarah and Naila for your good words and inspiration!

February 9, 2015

Slipping in Some Magic

Shoveling snow, shuffling sentences. I’m nearing the end of my novel’s first draft, full of sprawling snowdrifts of words. I’m tossing extra shovelfuls onto the banks, stray ideas to make everything more complicated before I look for a clear path through. Or at least a path. My way to the door isn’t exactly straight or smooth, and I’ll also be letting my pen shift as I find a way among the too many heaps of themes and conversations. In early drafts, I want diversions and too many possibilities. I’m not yet able to assess which ones will work best, and I’m still eager to be led astray.

Some of what’s underneath my snow banks will come to light, but I want to keep some of the dark mysteries, and what’s new for me, some magic. I grew up with a brother and sister who both loved fat books with dragons and spells like Lord of the Rings, but I stayed loyal to little houses and prairies, firmly keeping to realism. I married someone who loves fantasy, too, and I try to include such books in my curriculum. But when left to my own devices, I’ve pretty much stuck to the ordinary world.

But more and more I’ve wanted to put a bit of magic in a novel. I’ve attempted this before, and failed, but until now I don’t think I found the sort of magic I can believe in. For me, that’s connected to old and small things, often found or broken, which were sometimes what I played with as a child, vehicles for my games of pretend, which happened in the woods by our house or under a tree or porch. I’m working with the way that history seems to sweep me to another place. I’ve got an attic in a house that is some kind of haunted and woods that glimmer with some enchantment. How very different is a ghost from a person, after all? Setting forth the magic and listening to its possibilites, as I listen to characters, it took on a course of its own.

So here I am, creating places with odd histories and a twelve-year-old character who believes that anything can happen. Just the way writers do anytime we pick up our pens.

October 22, 2014

Alison Hawthorne Deming at Smith College

Last night I heard Alison Hawthorne Deming read at an event hosted by the wonderful Smith College Poetry Center. I’d read some of her poems and one of her four books of nonfiction: Writing the Sacred into the Real is a lot about the land’s beauty and fragility, and I was particularly moved by her evocation of life along the shore. While not a memoir, and more about place than particular people, she references her ancestor Nathaniel Hawthorne, becoming pregnant as a teenager and the fractures that made in her family, and the bond with her mother forged decades later.

Last night, standing under the Periodic Table of the Elements, which she said made her happy, Alison Hawthorne Deming read a little from each of her poetry books, including the manuscript she’s currently working on, with some especially poignant poems about her brother and cancer. She began with retellings or “re-entering the stories” of Eve and Persephone. Other poems explore relationships between art and science – two areas she says need each other, for neither alone can save the earth. She spoke of the genesis of “Rope,” the title poem of her most recent collection. She said she’d often walked along the rocky shore of the northern Atlantic and seen her father, son-in-law, and the man she was involved with picking up bits of rope they found washed up. “So of course when you have no idea what’s going on, you write a poem.”

She read from her latest book, Genius Loci, though not the long title poem that investigates layers of history in Prague, where, she writes in her notes, she first heard this Latin phrase and preferred it to “spirit of place” for its “echo of the pagan meaning of the word genius –the guardian spirit assigned at birth to a person, place, or institution.” She discusses being drawn to long poems in an interview with Terrain, saying these speak for our inner need for continuity, and “I like to use research to enlarge the poem.”

The themes of her prose and poetry blend, and sometimes one form slides into the other. In Rope, “Works and Days” is 45 numbered paragraphs with fascinating observations about frogs, Darwin, Merce Cunningham, mirror neurons, and other subjects. It begins with a quote from Mitchell Thomashow: “If the daily news is literally a substitute for morning prayers, then your reading of the day should reflect on questions of meaning and value.” More poems were inspired by and dedicated to friends who share her concerns, or about animals, the topic of her latest prose work, Zoologies: Animals and the Human Spirit. All of her work seems to rise from an effort to find beauty in a dangerous and endangered world, and weaves together truth and hope.