Jeannine Atkins's Blog, page 15

April 30, 2014

Finding Ways into Poems

During the past few months, age, grief, a heart condition, and who knows what else has brought more changes to my mother-in-law than in all the thirty years I’ve known her. She’s always been proud to be punctual and dependable, working at a library for many years without taking a single sick day, keeping regular habits, though those have switched in the past decade, so we’ve sometimes stopped in mid-afternoon and interrupted supper: “We thought we’d get that over with.” She’s famous for sticking to her opinion, which have recently been mostly about disappointments. Even food she used to like no longer tastes good. It’s a slippery world for all of us, as we navigate through conversations marked with denial and delusion, weighed down by depression. What’s true here? What can be of use?

My desk isn’t that dark – I’ve got tulips! – but these are the same questions I pose when writing a poem. A few weeks ago after visiting Alice in a hospital, I wrote in my journal as a way to order my mind back to what I’m more accustomed to, less ringing with desires that can’t be met. Hearing repetitions of small points of humor and compassion in my visit, and the way both Alice and I felt lost, I used those meeting places to structure Finding a Way.

That poem came together for me fairly quickly. More often I need to paste thick layers of words and phrases before I find a path from beginning to end. Listening for rhythms, the ends of breaths and echoes between words, I ask my more conscious self, who I’ve trained to be neither overly critical nor overly lazy, to note what may be of value, while paring away what’s not. Poet George Oppen wrote: “It is necessary to study the words you have written for the words have a longer history than you have and say more than you know.” We write and listen, as if following a conversation. If we keep at it long enough, and are honest about what we don’t know — perhaps because we’re writing fast enough to escape shame, or slowly enough to catch sight of something shy – we may catch something that’s deeper than our ordinary knowing. Maybe we can call it true.

April 28, 2014

Stumbling into Metaphors

Metaphors make connections, but stop short of drawing lines of “like” or “as” between them. There shouldn’t be a frame or pointing finger, but just a space where readers might or might not draw their own parallels, hovering between an object and meaning. Metaphor may be most powerful when something tangible is drenched with memories, perhaps suggesting something beyond the moment. Something big may recognize its shape in something smaller.

As a writer, I may stumble into an image that seems to speak softly back, and wonder if it will echo for someone else. Readers should stumble and wonder, too. Symbols aren’t meant to be a treasure hunt, but portals between worlds, which is why students get annoyed in classes where they’re treated with a point and shoot approach. Still, as a teacher I do my share of pointing, though with a moving hand. I recently asked my children’s lit students to get into groups to answer questions about BRIDGE TO TERABITHIA, which they’d bring back to the whole class. One group was tasked to see how much the disaster at the end was foreshadowed. I overheard them starting out saying, “Not much,” then get rowdier, laughing, “We’re such bad English majors! It’s everywhere!” They noted the rain and Biblical flood imagery, with the puppy held under a jacket so he didn’t drown, and the talks about death at Easter. They listed words such as “floating” laden with water imagery and noted Jess’s preferred medium is water colors, his fearful reaction to Leslie’s paper about scuba diving, her references to Moby-Dick –“the whale dies!” – and Hamlet – “Ophelia drowns!” The bully is described as a shark. Yes, death is kind of everywhere in Katherine Paterson’s beautiful classic, though also great themes of friendship, class, and gender. The group investigating the theme of imagination noted how the bridge between the land with domestic chores and worries and Terabithia’s freedom was first a rope, always in motion over the brook, requiring a leap of faith to land. Only after this bridge broke, after a mature awareness of death developed, was a more permanent bridge built, yet still made from a tree, which rots as well as grows.

Finding such connections can be exhilarating. As writers, we want to mirror our own sense of surprise upon discovering hidden paths and gates. Sometimes we can do this by developing the setting, showing where we tripped upon two things coming together, then stepping back. We may dust and polish, but leave enough grit so readers can discover as we did. Meaning peeks out the way character does among people we meet, perhaps in a glow around small gestures, often appearing after we say good-bye. Shut the door. Let it echo.

April 23, 2014

Jo March, Please Meet Katniss Everdeen

As the semester nears its end, we take a swift look at novels aimed for teens. AMERICAN BORN CHINESE considers shifting identities, and the graphic storytelling gives a nod to THE INVENTIONS OF HUGO CABRET, which we read earlier. We also go back in time to the somewhat utopian domestic world Louisa May Alcott depicted in LITTLE WOMEN, and a look ahead to the dystopia of THE HUNGER GAMES.

What do these two novels featuring independent girls who feel both at odds with society, and pressure to conform, have in common? Alan Scarpone pointed out how poverty and class are a theme in LITTLE WOMEN, though love eases deprivations that never reach the extremes seen in THE HUNGER GAMES. Food and song are ways to create community in LITTLE WOMEN, beginning with the Christmas breakfast that is given away, and ending with the family gathered for a picnic, once again singing. In contrast, starvation is a real danger in THE HUNGER GAMES, which makes that one burnt loaf of bread that Peeta tosses to Katniss, or was it the pigs, so special. Alicia Stein pointed out that Katniss must grow up fast, as is typical of many children today, while LITTLE WOMEN depicts a prolonged childhood and adolescence, for Mrs. March believes “children should be children as long as possible.”

Still, Jo must struggle in what Christina Kent wrote of as a social arena, “one that provides endless obstacles and challenges for her to defeat.” Both protagonists defy conventions, Jo by character and choice, and Katniss by necessity. Alicia noted that both are described as “tall and thin with dark hair and sharp grey eyes.” Jo wishes she could fight in a war she believes is just, to defeat slavery, while Katniss takes up her bow and arrow against others with reluctance, for no cause but survival. Both take on protector roles, providing for their families that are virtually fatherless. Katniss’s father died, while Jo’s father is away at war when the novel opens, then coming back near the end of the first part basically to chart the growth of his little women.

Marmee is forever giving, while Katniss’s mother responds to trauma by losing herself in grief. Since she’s inaccessible to her children, Katniss must act as both mother and father, bringing home food, as well as nurturing her little sister. Younger sisters motivate both Jo and Katniss to courage and sacrifice, and provide a place where the strong heroines can show their softer sides. Reagan Eckler noted that at the beginning of the novels, Jo is fifteen and Katniss sixteen, older sisters who are considered by thirteen-year-old Beth and twelve-year-old Prim as the people they need most. Christina Freitas analyzed how both Beth and Prim are “innocent, pure, and unfailingly kind, offering little sparks of hope as their lives falter or crumble around them.” Both are gentle rescuers of abandoned animals. She observed how while neither take up much space, their influence pervades the novels, serving as a kind of conscience. Jo tries to raise Beth’s spirits when sick, and Katniss looked for ways for Prim to feel hopeful in the face of their mother’s depression.

These are stories of struggle, but also romance. Alicia noted the parallels of Laurie and Gale as the friends who have romantic feelings that aren’t necessarily returned. Reagan mentioned how both are good looking, argumentative, and are thought by the girls as “the only people they feel they can truly be themselves with.” She notes that in both cases it’s the girls who reject romance, while ending up in a sort of love triangle. Family is so important to them that to consider these boys as like brothers is the highest praise. Stephani Spindel wrote that in the 1800s, “survival meant understanding how to play the social game” and how while both protagonists resist marriage, both ultimately end up in relationships that may surprise readers, but were those in which they came to “accept themselves for who they are.”

One book is realistic, written after Louisa May Alcott was asked to try to write something for girls, who she claimed to know nothing about. She preferred writing Gothic tales, but broke ground by showing the importance of the ordinary lives of young women in a book that was an immediate best seller and has never gone out of print. The other was inspired by the Greek myth of Theseus and the minotaur, Suzanne Collins’s knowledge of her father’s experience in the Air Force, and by watching TV reality shows, or more particularly, noting how a remote control can let viewers quickly switch between such shows and war coverage. At the center of both is a young woman who is a bit like Artemis, one independent by nature, the other taught by her father to use a bow and arrows. I can’t claim, though I wish I could, that both speak to this coming generation. HUNGER GAMES is more widely read by today’s teenagers, but it’s interesting to see some homage, if accidental, to Louisa May Alcott’s masterpiece.

April 11, 2014

Love Calls us to the Things of this World

Last year for Poetry Month our local library asked some of us to gather to read favorite poems, which made for a most civilized evening. We wanted to do it again, but personal schedules conflicted with the library’s and town meeting. “Maybe we should wait until next year,” I suggested over our email exchanges. Marianne wrote, “I don’t want to wait a year. Tom and I will have it at our house.”

So she set out tea, and I brought banana bread. Seven of us read poems by Marianne Moore, Billy Collins, Dante, Coleridge, Noel Coward, Wislawa Szymborska, and several from Garrison Keiller’s Good Poems. We talked a bit about what we read and poetry in general with short related tangents. Tom mentioned his mother coming from Wales, and how he was stationed for army training there during WWII, and how he’s thought “five thousand times how lucky I was to land there, and how people were touched by the American chap who knew about five Welsh phrases.” The room filled with the gratitude of his memory, and our pleasure in reading together.

Yesterday in front of the post office I saw another neighbor who couldn’t make it to the gathering. He asked me what I’d read, and when I replied “The Writer” by Richard Wilbur, he said he’d just thought of a favorite poem by him while passing a line of laundry hung to dry. Here’s a video of Richard Wilbur reading Love Calls us to the Things of this World.

Richard Wilbur says the poem was inspired by a line from Saint Augustine. He mentions he likes how he managed to use the word “hunks” in the poem, though out of keeping with other words there, “which is precisely why I like it.” And he mentions another poem in which he used the word “reinforced concrete, without that word sinking that particular poem.” It’s a reminder of how we like unity in a poem, but also surprise. A favorite poetry writing prompt is to find or be handed three random or varied words and try to fit them into a poem. This can stretch the mind to a triangle of directions, with something new found in the corners.

For more Poetry Friday posts, please visit Michelle Barnes.

April 8, 2014

The Eye is a Door

Maple branches are turning red. I heard peepers in the pond. A friend reports the green tops of crocus, though she said her children carefully raked away snow and made a little rock fence around the sacred area by the door so nobody would step there. Almost spring, but to get me closer to its spirit I just saw thirty or so big photographs of beautiful places that Anne Whiston Spira, professor of landscape architecture and planning at MIT, took around the world. The photographer and writer has received a Guggenheim Fellowship and an international Cosmos Prize for “contributions to the harmonious coexistence of nature and humankind.” She writes, “Photography is to seeing what poetry is to writing; a concentrated way of thinking, a condensed telling, a disciplined practice that may produce insight.” Here are two examples of her work from over the past thirty-five years.

Mount Rokko Chapel, Kobe, Japan, July 1990

Skaftafellsjökull (Vatnajökull), Iceland

Anne Whiston Spira writes: “Why a door and not a window? A window is something to look through, but a door is something to pass through; crossing a threshold, one enters a new place. To see, to really see, is to open a door. To pass through that door is to arrive at a new understanding.” More pictures can be seen on the website, but if you can get to Northampton, MA before August 31, you can have the treat of seeing pictures longer than your outstretched arms, full of detail, at the Smith College Museum of Art.

April 5, 2014

Finding a Way

Finding a Way

Since arriving by ambulance in the dark,

my mother-in-law has been in a different room

every day. So at the front desk I ask for Alice’s room,

which the volunteer gives,

and says, Do you need directions?

I do, but say, I’ll get lost anyway.

Now I take that for granted, along with landmarks

of gift shop, a room with a fish tank,

the view of brown wisteria vines,

the nurses who ask, Can I help you?

Are you lost? Do you know where you’re going? Honestly,

I can’t remember their words, but all are kind.

As I step through the doorway, Alice looks at me

as if I might be anyone, so I say, It’s Jeannine,

and greet the friend who sits beside her bed.

Alice tells me they never brought her ham sandwich.

Her friend shakes her head.

Well, they brought it, but it was turkey, Alice says.

Her friend shakes her head, and whispers, She ate a bit.

More loudly she says, Some people can’t tell ham

from turkey. Then we talk about orange juice.

Alice asks me, Are you Stephanie Knowle?

I say, No.

She says, But you used to be. Before you were married.

I wish I knew who Stephanie Knowle was. A young man

arrives with a neon orange strap and a steel walker.

He says, I’m going to help you try walking.

Alice says, No, but she is interested in his running shoes.

He tries to charm her. Her friend and I offer bribes.

If you walk, maybe you can get home. She still says no.

When the man leaves, Alice asks, Was that the organist?

Apparently I say no a lot, too. I want

to be home and pull a hood over my head,

slip on my fingerless gloves. It’s April, but it’s cold.

I want to break forsythia to force, make banana bread

and have that take a day. For a few hours, no more phone calls

even with people I love. At least I know my way out:

two turns before the fish tank. I tell Alice, I’m going now.

She bends her head for my kiss, then says,

You have to go home and write.

April 3, 2014

What I’m Reading: Mary Poppins, She Wrote

Leaving the theater after seeing Saving Mr. Banks with my daughter, I spoke of my delight, but half way across the parking lot, I started wondering about how much truth was woven into the story about an author, her beloved books, a beloved producer, and a talented team of song-writers. I loved Emma Thompson as Mrs. Pamela Travers dancing with the Sherman brothers to songs they wrote for Disney’s Mary Poppins, but I wondered how closely such images adhered to life. I was enchanted with Tom Hanks as Walt Disney and believed while watching that his insight might lead Pamela to a sort of epiphany, but was this rather too tidy? Was P.L. Travers truly so snippy, so rude, so Mary-Poppins-ish? Emily looked to her phone to answer a few of my questions – yes, Pamela’s father’s first name was Travers, which she took as her pseudonym — but after seeing the movie again with my husband, I read Valerie Lawson’s 1995 biography, Mary Poppins, She Wrote. Can a biography unravel, or add another layer to the life of the girl born as Helen Goff? Can I write clearly about two books and two movies that in many ways slip-slide together, taking on the ways that tales depend on the tellers.

Valerie Lawson seems a hard-researching and reliable narrator, taking on this life partly as she was curious about a writer who, like herself, hailed from Australia. She seemed never swept toward criticism or un-tempered adoration, and if she felt either at times, nicely covered her tracks. The book proceeds chronologically, with the past being shown mostly through summary, not the involving scenes a movie gives us. We hear about the charm and self-destructiveness of Pamela’s father, but don’t really see or feel it, though it appears he did read a poem written by his little girl and say, “Not exactly Yeats,” but not on his deathbed. And while Valerie Lawson speculates some on literary sources and the impact of the death of Pamela’s father when she was young, this isn’t as directly tied together as the movie suggests, weaving from the past to present obsessions.

Valerie Lawson details how she wrote poems, essays, and much beyond the series of books that brought her fame as P.L. Travers: she chose initials as an author, not as some women have hoping to be taken as a man, but wanting to be seen as neither male nor female. And she was so worried about being pigeon-holed or even known as a writer for children, that she often went out of her way to point out her adult audience. However, she thought of Beatrix Potter as “one of the archangels,” and loved “her understatement, her bareness, he surrealism, her non explaining.”

But before the books that brought her some fame, there was the angst of a young woman trying to make a living and a life in theatre, as a writer, and doing odd jobs in London. I kind of wished Pamela could admire Yeats, T.S. Eliot, and other poets without the crushes, but who of us is as dignified as we might wish? We hear of her traveling to Dublin and deciding to stop at “the Lake Isle of Innisfree,” though it was raining, and the boatmen scoffed that around there they called the place Rat Island. She cut down a great armful of rowan branches, heavy with berries and symbolism of death and resurrection, which she carried back on the boat, train, and street, arriving dripping wet at Yeats’s home. She got dried off, and touring the rooms later, saw a single sprig in his study. Was the lesson that less is more, or she shouldn’t cut branches sacred to druids and fairies, or she might be try to be a little more cool?

When Pamela turned forty and yearned for a child, she jumped at the chance to adopt the grandson of an Irish publisher, a friend and biographer of Yeats. It’s said that she chose the better-looking baby, and was affirmed in her choice by an astrologer. She put on a wedding ring and told stories. I think we can be happy Saving Mr. Banks chose to skip past the years of loneliness and motherhood, the episodes of Pamela giving illustrator Mary Shepherd a hard time, a series of shady gurus, the traveling – though I was interested to learn Pamela spent time in Russia, Japan, New York City, Maine, and the Southwest, and annoyed undergraduates at Smith College and Radcliffe. The movie works well zig-zagging between childhood and her early sixties, when she left a flat in what looks like could be Cherry Tree Lane for Hollywood.

The biography tells us she was very happy to get a generous sum of money for movie rights, at a time when her books weren’t selling well, and shortly after her adopted son, Camillus, had learned by running into his twin brother in a bar that they shared living parents he’d never heard about. A rocky mother-son relationship ensued. Maybe it wasn’t the worst time to go to Hollywood, though perhaps it wasn’t the best. Both Mary Poppins, She Wrote and Saving Mr. Banks give versions of a fraught relationship with Walt Disney, who took the episodic stories that make up Mary Poppins and looked for an arc. He mused on the song “Feed the Birds” and chose a retired actress whose spread skirts gave her the shape of a Madonna or trinity, with the saints and apostles of St. Paul’s Cathedral looking down and smiling, “though we can’t see them,” at those who fed the birds or the poor. Walt Disney looked for a reason for a family to invite a stranger into the home, then a reason for her to leave. It seemed Mary Poppins had to be there to save the family, while the stories are more zen-inspired, with moments of delight, revelation, and mystification, with little concern for lessons or a narrative shape within the collection beyond that the nanny comes and goes as the wind changes.

Mary Poppins in the book is not a whole like Mary Poppins in the movie. It seems Pamela Travers hadn’t heard of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s advice to novelist who sold movie rights: to throw the book over the Hollywood border, grab their money, and run. In fact we’re sympathetic to how she feels robbed of her character. Tom Hanks as Walt Disney is sympathetic, too, saying he’d felt the same pain letting go of some control of Mickey Mouse. But there’s some tension in the corner of his mouth. Walt Disney was a different kind of charmer than Pamela’s father, but perhaps most charmers have a combination of liking people with a healthy dose of self regard.

Pamela Travers cried at the L.A. premier of Mary Poppins. Who knows if she was re-experiencing the sense of loss she felt at the death of her parents? Mary Poppins, She Wrote alludes to a lifelong search for her lost father, ending with the sense that it’s the search that matters more than the finding, and that while Pamela didn’t find her Mr. Banks, she did find herself amid all the looking. The importance of the quests over the destinations is a theme that mattered to Pamela, who believed that our inner selves are not hidden, but lost, and we may spend our lives looking for them. But where’s the movie in that? There’s a reason zen koans aren’t made into films. Most of us prefer narrative arcs to the often more realistic shapelessness of life, not simply craving happy endings, but the hero’s journey of separation, adventure, and return. We know that Walt Disney didn’t accept Pamela Travers’s phone calls and she publically spoke ill of him, but together they collaborated on something that matters to many. Creativity, which both book and movie take as a theme, is full of mysteries. Much as I’d like to stand by what seems to be fact, and am grateful for all I learned from Mary Poppins, She Wrote, I’m taking the side of Saving Mr. Banks, with its smiles, tears, and truths that are close enough.

March 31, 2014

Believing Children

Moving into a discussion of Mary Poppins, one of my students spoke about how he’d always been bothered, both in the book and movie, by what he called the bubble-bursting moments. For example, after the tea party near the ceiling, or the middle-of-the-night visit to the zoo where they talk to animals, Mary Poppins told the children not to be ridiculous, that no one could eat in the air and respectable people like her spend their nights in beds. My student asked why she lied. I couldn’t really answer. Did it have its roots in P.L. Travers’s interest in Zen, a tradition more about riddles than answers, but not one I claim much to understand? This weekend, I asked my friend Jess, a yoga teacher, who told me about aiming for effortless effort, trying without trying. In a state in which we’re always beginning, uncertainty may be the closest we get to truth. And then Jess said, “But that bothered me about Mary Poppins, too. Why shouldn’t children be believed?”

illustration by Mary Shepherd

A favorite moment in The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe is the way Lucy stands by what she knows happened beyond the wardrobe no matter how much she’s teased, and the good Professor points out to Lucy’s older sister and brother that she has always been honest, so why shouldn’t they listen though she spoke of something that to them seemed incredible? A student who noted he had no problem identifying with Lucy though he’s a guy – “she got into the wardrobe first and she got a dagger as a gift. Cool.” – may have also been drawn to Lucy’s confidence.

And in The Secret Garden, Mary has tantrums for a number of reasons, not all sympathetic, but I’m with her when she is furious when told that she doesn’t hear crying behind a closed door. She is certain of her own ears. I’m sure there are other books that take this as a theme. But where does this leave us with Mary Poppins? Those bubble-bursting moments didn’t bother me much, as for the most part, Jane, though not always Michael, seem to accept them. There are plenty of parts of Mary Poppins not to like. Unlike the sweetened Julie Andrews version, in the book she’s curt, conceited, and perplexing, but she leads us into magic.

Still, so many young readers are Hansel and Gretel, innocently entering forests, perhaps never knowing the back story, like readers or listeners who overhear the conversation between the parents: There’s not enough food. Somebody in the family has to go. And if Hansel or Gretel were to learn and confide about this, would they be believed, or told that parents couldn’t possibly act like that? Children may ask for so little. To be fed, to be safe, to be loved. The movie Mary Poppins takes up this theme in showing how Jane and Michael, who have a good roof and full table, yearn for more. I just listened to an old interview in which the Sherman brothers, who wrote and composed the songs, talk about “Feed the Birds,” which all considered the heart of the movie, with its message about how a need to connect can be met with tuppence, or just a bit of attention. Believe me can be another cry for See me.

I’m writing more about Mary Poppins, a biography of Pamela Travers, Mary Poppins, She Wrote, and Saving Mr. Banks in the next day or two, so if you haven’t heard enough about the sometimes confounding book and author, please stop back by!

March 28, 2014

Miss Emily and Invoking the Past in Verse

Miss Emily by Burleigh Mutén begins with a two children galloping on imaginary horses, meeting up at the woodpile, “where all good plans are made.” Soon four children stretch and slither like slugs to meet their neighbor who kneels near the Great Pink Bush. Instantly we feel within a child’s world. The theme of imagination and its joys is found in more escapades that will hold children’s attention while they’re welcomed to poetry. Miss Emily has fun with metaphors, riddles, and occasional long, Latinate words, which are sometimes capitalized, as in some Emily Dickinson poems, but here feel more fun than serious – or is this just Serious Fun? Maybe it doesn’t matter, just as in the book lines cross between pretend and true, a blurring suggested by Matt Phelan’s charming graphite drawings.

I love this novel for young readers, and it’s always a pleasure to see a friend’s work find its long way into covers. And what lovely covers these are: thank you Candlewick Press, which offers a teachers guide and author notes! Burleigh and I have shared precious conversations about poetry, from its genesis to marketing, over meals and walks around Amherst. I have a recent memory of her saying, “Don’t you just love to make line breaks?” Her smile pushed up her bright cheeks, and of course I said yes. A few years ago, she invited me to her house, where she’d set bread and cheese on her wooden table with a view of the woods, and we planned a workshop about invoking people from the past. Our workshop was turned down, but we had a memorable afternoon talking about, among other things, how first she decided to write about Emily Dickinson’s playful side, and then decided to put the narrative in verse. She felt some fear but mostly joy to reconnect with an inner poet she’d known in her teens, but abandoned for a while.

“It is hard to own being a poet,” I found in my notes from that afternoon. Here are a few more:Line breaks as places of power. Literature moves fastest through dialogue. The chutzpah and humility to speak for someone from the past. You have to be open, like in meditation. Go beyond facts or legends through imagination, its compassion. To play is to take a chance. I like the language of incantation, but prefer that people not think I’m too swoony or over the bend. Feels all about listening. Writing is about confidence and uncertainty, faith and disbelief, forging ahead and hesitation. Linger on details. I care more about potatoes than divorce.

There’s a lot more. I’m not sure what I said or what Burleigh said, and it didn’t matter at the time. All of it still makes sense to me, except the potatoes and divorce allusion – which of us said that? –though I do tend to obsess more about what’s on a table than abstractions. And am very fond of potatoes.

For more Poetry Friday posts, visit Mary Lee at A Year of Reading.

March 26, 2014

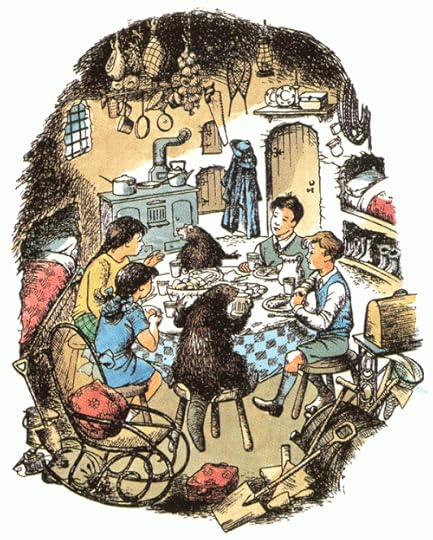

Sharing the Table in Children’s Literature

When my class recently read The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, I brought in two small boxes of Turkish Delight, because I remember first reading that novel and wondering what the candy that Edmund craved enough to endanger his siblings tasted like. It’s a defining moment when Edmund first accepts the candy, which one student thought of as a step up from gummy bears, from the White Witch, just as the brown eggs, lightly boiled, buttered toast, and sugar-topped cake that the faun prepares for Lucy in his snug home makes her a citizen of Narnia. When Lucy returns with Susan and Peter to find Mr. Tumnus’s house ravaged, she thinks of that shared food and knows that scared as she is, she can’t turn back. She owes that faun, and will do whatever she can to save him. Lucy, Susan, and Peter becomes allies with Mr. and Mrs. Beaver over fresh trout, potatoes, sticky marmalade rolls, and tea. The fact that Edmund can eat and disappear signals us to how dangerously he might betray them.

When someone suggested to C.S. Lewis that he used food because he couldn’t write about sex in his books for children, he told them, No, he just really liked food. Meals and treats can be tricks or pacts, depending on how they’re doled out. Perhaps we first meet this motif in fairy tales. Hansel and Gretel get in a predicament because the family is starving. They first trail bread crumbs, then are lured by a candy house. Another fall is caused by Rapunzel’s father stealing rampion, a sort of lettuce, from the garden of a neighbor, and trades in his daughter to save himself and his wife. In Snow White, one bite from the witch’s poisoned apple turns the plot.

Food and fire can devastate, but perhaps more often stand for home, safety and love. Good and food is separated by a letter, as I realized when I mis-typed it. Peter Rabbit starts out with a warning about his father ending up in Mrs. McGregor’s pie. Peter journeys forth regardless and feasts on lettuces, French beans, and radishes before being discovered by the farmer with a hoe. He escapes, but his mother gives him only a table-spoonful of chamomile tea for supper, while Flopsy, Mopsy, and Cotttontail get bread, milk, and blackberries.

We just read Mary Poppins with its gingerbread with stars, plum cakes, wholemeal scones, tapioca, sherbet, and licorice offering times of togetherness and delight, maybe most particularly when the tea table is in the air under the ceiling, combining those images of flight – the arrival on the umbrella, the conversations with stars – with what’s homey. We read Peter Pan, where the hero who won’t grow up blurs the real and make-believe so much that he can eat imaginary food and get fat, though in this play-turned-book, sewing and tidying are more metaphors for lulls between adventures than eating.

Next we’re moving on to books for slightly older readers. In The Secret Garden, the fresh milk and rolls with currants that Martha and Dickon’s mother, Mrs. Sowerby, sends Mary and Colin to eat secretly, so their renewed appetites won’t be guessed, is almost as healing as the garden. Little Women starts out with Christmas, and the four sisters decide to pack their delicious breakfast of muffins, buckwheat cakes, and cream into a basket to give to those who are needier. There’s never such bounty in The Hunger Games, for food is scarce where Katniss lives. But we learn of her sisterly love, as fierce as what we find among Jo, Amy, Meg, and Beth, when Katniss barters a goat her little sister can care for and make cheese. And that burned bread, which we’re never quite sure is an accident or pure gift from the baker’s son, plays a big role.

Now I’m getting hungry. What are your favorite meals in children’s books?