Jeannine Atkins's Blog, page 9

September 15, 2015

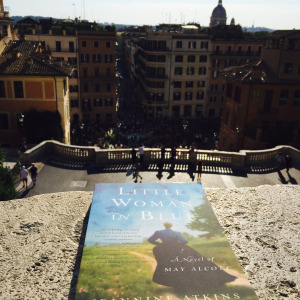

Little Woman in Blue: Publication Day!

After spending many years with May Alcott in the form of a manuscript in and out of a drawer, with my patient writing group there to help shape it, and my husband to cheer and edit, it’s wonderful to have more people know more about two sisters who crave wealth, travel, and fame as an artist or writer in nineteenth century Massachusetts. All these years later, I still love thinking, talking, and writing about May. Part of me wants to move on, and I am, with other books in the works. I need the creative roughness that keeps me sane, or should I say stable? And part of me loves seeing May again through new eyes, sharing that friendship. Isn’t she great?

Big thanks to those who’ve let me know that copies of LITTLE WOMAN IN BLUE: A NOVEL OF MAY ALCOTT are arriving in the mail, and for kind comments. Library Journal says: “Devotees of Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women will be intrigued by this fictionalized biography of the women behind the characters.” I’m grateful for Kelly Fineman’s thoughtful and warm review on Writing and Ruminating, including these lines: It is my opinion that Little Woman in Blue … is the book for every woman I know. And would be great for book clubs everywhere – especially those who loved books like Loving Frank by Nancy Horan.”

Praise is sweet, but so plain old “getting it,” seeing some of what I did. To be known was what May longed for from her sister. At TeacherDance, the well-read Linda Baie wrote: “Jeannine Atkins shows May’s inner questioning of women’s roles in society at that time, that they cannot have both the passion of art and of marriage. And she shows May choosing “more,” an admirable and risky choice, sometimes even today.” Thank you Melodye Shore for writing at A Joyful Noise: “Alcott aficionados will find much to love between its covers, as will readers for whom this is a first introduction to the sisters in Little Women. Rich imagery. Relatable characters. Settings that are true to an era, and a story that celebrates May’s life, aptly published during the 175th anniversary of her birth year.”

Debbi Michiko Florence writes, “What Atkins paints here is a vivid and layered portrait of younger sister May, who was an artist, a dreamer, independent, and loyal. … I couldn’t stop turning pages as I wondered if May would find success as an artist, find love, or see her family again.” She interviews me at Welcome to the Spotlight and offers a book giveaway open until September 19: you just need to comment at the link.

While today is the official launch day, publishing is quirky, and LITTLE WOMAN IN BLUE: A NOVEL OF MAY ALCOTT has been showing up in mailboxes. I scheduled launch events for beautiful October to make sure the books were on hand. I could not be more excited that my official launch is being hosted by the Odyssey Bookshop 9 College St. South Hadley, MA on Oct. 13 at 7 p.m. More details soon, but there will be cider, baked goods, back stories, and fans!

We’ll also celebrate in May Alcott’s hometown at Barrow Bookstore 79 Main St. Concord, Mass on October 17 at 4:30. This shop is run by two sisters who have a history of working in Orchard House, where May Alcott grew up. We’ll be sure to have a good time.

I look forward to seeing Boston area friends and readers at wonderful Porter Square Books 25 White Street Cambridge, MA Oct. 23 at 7 p.m.

I’ll be part of a Women’s National Book Association Panel at Brookline Booksmith, 279 Harvard Street Brookline, MA. on October 27 at 7 PM. Moderated by author Lisa Borders, the panel will include novelists, Lauren Acampora, talking about THE WONDER GARDEN, Heidi Pitlor, author of THE DAYLIGHT MARRIAGE, and Virginia Pye, author of DREAMS OF THE RED PHOENIX.

I’ve got some interviews coming up this week, and I thank M.K. Tod for asking me to write about Finding Fiction’s Sweet Spot Between Past and Present at A Writer of History.

I’m not the first to say it, as is the case with most true things, but it takes a village, and I’m enormously grateful for cheers and contemplation from strangers, family, and friends, for librarians and booksellers, and She Writes Press.

It will be a busy month, but I’ll still be making time to write something new. There are so many stories. I appreciate every one of you who are making time for this one.

September 14, 2015

Emily Dickinson and Friends

It was great to tour the Emily Dickinson Museum with Kerry Madden, a writer friend who was briefly in Massachusetts, with Burleigh Mutén as our guide. She led a small group through the Homestead, where Emily Dickinson was born and died, and the once elegant Evergreens next door, which belonged to Emily’s brother Austin, his wife Susan, and their family. Every reading and every guide brings a new angle to the woman and her poems. I knew from conversations how much Burleigh, who wrote Miss Emily for young readers, loves Emily Dickinson, but to hear her speak in the historic house really brought it home. “Tender” was a word Burleigh used several times describing relationships, bringing up the gifts of words or small things exchanged. She passed around a cup of chestnut burrs that Emily used to describe the color of her hair. When we looked at the replica of the white dress, Burleigh pointed out the pocket where the poet carried pencils.

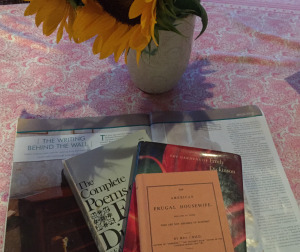

She mentioned the chocolate wrappers and backs of envelopes that Emily wrote on, though the family wasn’t poor. She told us that Emily’s father had given his wife Lydia Maria Child’s popular The American Frugal Housewife, which was a book I’ve used for reference, filled as it is with the details of household chores and recipes. It is good to know how your characters might have made plum wine or pickles, and what sorts of soap were used for linen.

Burleigh told us about the small conservatory Emily’s father had made for his daughters, and showed us copies of pressed plants – apparently hundreds – she’d put into books. The gardens are restored in many respects to years past. I took this picture of a fig tree and some button-or-tassel-like plant I hope someone can identify.

Occasionally Burleigh paused in the talking about Emily to read a poem, without ceremony beyond the words themselves. The poems seemed integrated into the dailiness, but the room brightened. After seeing Emily’s newly restored bedroom, with pink flowered wallpaper, we sat in a room bare of the historic, but with room for folding chairs, to think more about composition. I hadn’t known about the evidence of Emily Dickinson’s revision process left on the pages of the small books she sewed together, found by her sister, Lavinia, in a chest after her death. In a room with a clever board that opened and hid words, Burleigh demonstrated the possible replacements for words within the published poems. Apparently Emily left little markings that don’t appear in the poems as we’ve come to know them. She sometimes put rings of words around a poem, which she considered as replacements, but not always with an indication of which word should be finally used. Each editor chose what those they liked best.

And now there’s more to read, always, including an article in the current issue of Preview Massachusetts about the long research behind finding wallpaper samples and worn parts of floorboards that suggested floor plans.

September 12, 2015

Washington DC: A Quick Visit

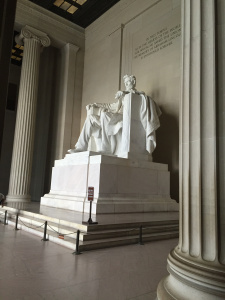

So lovely to wall down the Mall and see one of my favorite memorials for my favorite president.

An email from my intrepid publicist, Caitlin Hamilton Summie, led to hasty travel plans and a fast visit to the Capitol to record a short passage of me reading Little Woman in Blue: A Novel of May Alcott for public radio. This was the first time I’ve had my title considered in the seconds it takes to say. I’d chosen five little passages, then the producer picked two. I had practiced reading to keep my pace brisk but understandable. But I felt like the amateur when going through multiple readings, trying to make each one sound fresher than the last. Some words have so many syllables! I pretty much got down enunciation, but was asked for emotion. Without hands to wave! Producer Peter Johnson reminded me that on radio, you may have a few seconds to capture someone before they change the channel. But no pressure.

I LOVE my characters. I DO. But putting depth and height into my voice without sounding false was a challenge, and I’m thankful for Peter’s wise and patient coaching – while realizing no one has coached me in anything for a while. It was humbling. I did my best to pronounce Little Women as if I’d never spoken that title before. I mustered as much passion as I could for muskrat and heron, while Peter reminded me that Walden Pond is not any old mud puddle. I tried to put a sense of glorious history into my reading.

In the end, we were both satisfied, and I’ll post a link when it’s on The Author’s Corner, and perhaps on its way to public radio stations. Meanwhile, you can listen to other readers on the link, including President Jimmy Carter. I expect he needed less practice and prompting, plus that accent goes a long way.

I was happy to get back to my less studied way of talking as I met poet/writer/friend Sara Lewis Holmes at the gorgeous Library of Congress. We walked around amazed by the marble pillars, mosaic ceilings, and Thomas Jefferson’s library.

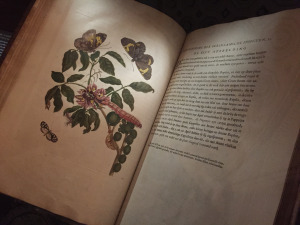

Since Maria Sibylla Merian is one of the subjects of my forthcoming Finding Wonders, it was thrilling to find her books of botanical drawings encased under glass, like the Gutenberg Bible, though this in a section honoring explorers.

It was also fun to go to the children’s room and spot Borrowed Names on the poetry shelf. Of course the library holds over 36 million books, so it’s not alone: but I was happy to see it displayed. Then Sara and I had tapas and wine and talked poetry.

It was great to meet my cousin Eileen and laugh and see more art before flying home. Earlier I managed a run-through of a few halls in the Smithsonian American Art Museum. I saw Louisa May Alcott as I got lost in the adjoining National Portrait Gallery.

Fortunately I learned from my organized daughter about planning museum trips with specific works in mind, so had researched which Edmonia Lewis sculptures would be on display. Readers of my last blog will know how I’d found, sort of, this sculptor in Rome. Perhaps ten years ago I’d seen Edmonia Lewis’s Death of Cleopatra, which got lots of attention at the 1876 World’s Fair, at the Smithsonian in a smaller room, but I like the casual company she keeps here down from desks where some people studied.

Other of her smaller sculptures were behind glass in the Luce Foundation Center, where you happily get to see work that otherwise would be kept in storage. What a great museum in a beautiful city!

September 7, 2015

Women and Art in Florence and Rome

My daughter and I are back from a great trip to Italy where we walked a lot, ate a lot, and visited a lot of museums. I loved my first ever gondola ride in Venice, a wine tour in Tuscany, and learning from my favorite art history major about Renaissance and Baroque art, though I’m usually looking for the women. Venice with its lovely boats and waterways was a bust in this respect. The Accademi Galleries is supposed to hold pastel portraits by late Baroque artist Rosalba Carriera, but there was construction underway, and maybe they were temporarily in storage.

We did a bit better in Florence, seeing work by Artemisia Gentileschi (1593-1656), who is featured in books about women artists and novels including Susan Vreeland’s The Passion of Artemisia. She was inspired by Caravaggio, whose work was well-represented in many churches and museums, though Emily told me that he was a bit of an outcast in his day, with some patrons objecting to things like how he painted holy men with realistically dirty feet. We saw Judith and her Maidservant at the Pitti Palace.

And Judith Slaying Holofernes at the Uffizi Gallery. This is thought to have been painted for Cosimo II de’Medici, but because of its violence was put in a dark corner (though the Medici family knew plenty about violence, and this theme wasn’t uncommon). Artemisia Gentileschi wasn’t paid for this work, until her friend Galileo Galilei, who wanted to be an artist before he began focusing on science, came to her aid.

This makes me fond of Galileo, though he’s better known for making telescopes that changed his and our view of not only the sky, but the cosmos.

He saw that Venus had phases like the moon, which showed it rotated around the sun. The moons he observed around Jupiter did not circle the earth. It looked like the earth wasn’t at the center of the universe, a point that got him called a heretic by the church and put under house arrest for almost twenty years. About 100 years later, the Catholic Church admitted Galileo had a point, had his body dug up and buried under lovely tomb in the Basilica of Santa Croce.

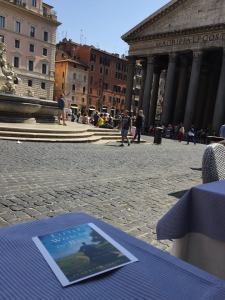

Sometimes you have to bring along your own signs of artists. May Alcott studied lots of paintings and sculptures in Rome in 1870. I let her enjoy lunch outside the Pantheon, which includes the tomb of Raphael, one of her favorite painters.

I escorted her to the Spanish Steps, where back in the day artists gathered in the morning, often choosing models who sat there or around the Bernini fountain.

Nearby, a street of houses with big doors that once let in big chunks of marble and let out statues is now filled with swanky shops. I ordered cake and a latte in a restaurant in what may or may not have been Edmonia Lewis’s studio.

May-or-may-not is a theme in her story. We know she worked in a studio where Canova worked, as he did here, and then the Tadolini family, whose work is displayed. I added Edmonia Lewis’s name on my napkin and signed it in the guest book. Because one thing Rome has besides layered history is ghosts.

I wove some of my knowledge of and questions about this sculptor into Stone Mirrors, a verse history to be published by Atheneum in 2017. For those who want facts now, Harry and Albert Henderson’s excellent biography is available as an e-book. Edmonia Lewis was the first person of color to receive international acclaim as a sculptor against odds that haven’t changed enough over the past 150 years or so. According to those fabulous researchers who call themselves the Guerrilla Girls, in most major museums, only about 4% of the art on display has been made my women. And so now I’m back on the porch, jet-lagged and doing laundry, writing by asters and hydrangeas.

August 21, 2015

Peeks into May Alcott’s Paris

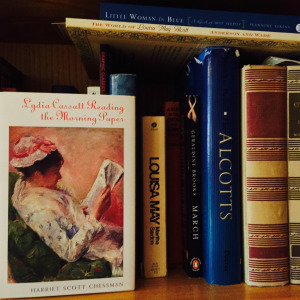

During the years of writing Little Woman in Blue: A Novel of May Alcott, I was delighted to catch sight of May wherever I could. Most often this was in biographies that focused on her sister Louisa May Alcott and sometimes their parents, Abigail and Bronson. I also came to know May from memoirs of nineteenth century neighbors, such as novelist Julian Hawthorne and sculptor Daniel Chester French. I was delighted to find May in two novels by contemporary women that feature Mary Cassatt. Both May Alcott and Mary Cassatt were expatriate painters in Paris at the same time and became friends. I liked to imagine walking in on one of the Thursday night soirées at the Cassatt family home in Montmartre, or listening in as May and Mary rode in a horse-drawn carriage through an elegant park.

One book that gives a fictional peek into their lives in 1870’s Paris is Harriet Scott Chessman’s Lydia Cassatt Reading the Morning Paper. This spare and lyrical novel shines with reflections on art, family, the nature of memory, and mortality. Like my novel, there are sketches of sisterhood, but the relationship here is gentler. Lydia Cassatt has Bright’s disease that she knows will cut her life short, and seems mostly resolved to her role as model and muse for her hugely talented sister. Such a role would never have contented May Alcott, who was blessed with good health and felt determined to make her own mark. But I like the theme of the person who finds the courage to contend with the limits illness forces upon her and to find grace in the milestones of an inner life. It’s not easy to live in the shadow of someone famous, and Lydia does so with affection and courage. The story is told in her voice and in present tense, and as seems befitting with someone who struggles with pain and for whom energy is at a premium, the narrative is written in vignettes with pauses in between. It’s structured in five sections related to five of Mary Cassatt’s paintings, which are reproduced here, and show Lydia’s observant eye and an artistic sensibility that only Mary, and then we the lucky readers, can share. We see Lydia with embroidery hoops or at a loom. “I yearn to be simply present in this day, filled for the moment with color and shape, my own hand urging the needle through the silk.”

I Always Loved You by Robin Oliveira is told as if by Mary Cassatt, framed with the mention of letters found after the death of Edgar Degas, when Mary helped clean his studio and hunted for these souvenirs of their deep friendship. The nature of love between them is not as direct as the title suggests, but complicated, ambiguous, and shifting, as both Mary Cassatt and Edgar Degas put much of their time and passion into painting. We get to know the confident woman from Philadelphia and the gruff Frenchmen. Mary is shown as a prudent businesswoman, but did more than tally “coin and admiration,” caring more about “the moment, the breath, the seeing.”

The novel focuses on Mary’s relationship with Degas, but we also get to know her sister, her parents who were more conservative than she was, and other artists, including Berthe Morisot and Edouard Manet. Perhaps most interesting for me was the way the novel opens with a scene of Mary Cassatt and May Alcott. To avoid the potential awkwardness of dialogue between Mary and the similarly sounding May, Robin Oliveria wisely chose to call her Abigail, which was May’s given name (as a young woman, May chose to use her middle name, since it was prettier, and her mother’s maiden name, passed along to her two most creative daughters.) The friendship of Mary and May is full of warmth and trust, a refuge as Mary contends with much and comes to question Degas’s statement that “Only paint was honest.”

I enjoyed both these novels for the depiction of Mary Cassatt’s struggles and successes, and the enticing glimpses I got of May. With Little Women in Blue: A Novel of May Alcott I give May a stage of her own. I hear the novel is in from the printers and starting to be stocked, so you kind people who’ve pre-ordered may get copies soon. I’m excited!

August 17, 2015

The Isles of Shoals

Slathered in sunscreen, with hats we needed but sweaters we didn’t, my sister, two of her daughters and I set aboard the Thomas Laighton at The Isle of Shoals Steamship Company in Portsmouth, NH yesterday. I wanted to set foot on one of the nine islands that I spend a lot of time looking at from the coast of Maine. I learned that some of the islands are in Maine and some in New Hampshire, and from them you can see Massachusetts, too.

Above is White Island where I’ve read about Celia Thaxter spending some years of her childhood. Her father, Thomas Laighton, was the lighthouse keeper. He also helped develop the islands, including see that an inn was built on Star Island, which Celia would later help run. In the nineteenth century, many well-to-do guests came to escape the heat and horsey smell of Boston, including poet Longfellow and novelist Hawthorne. Celia was also a respected poet and writer at the time, as well as a talented china painter.

The big inn on Star Island, where we landed and walked, is now used as a retreat center for UU and UCC groups and families. I love how they nod to this history with a room with a view and photos of notables from yore.

This picture is of Celia Thaxter’s brother, Oscar, who lived on the small island for about ninety years.

We walked around and saw scenes like this.

Here’s a picture of the tallest grave in New Hampshire taken from inside the small stone church.

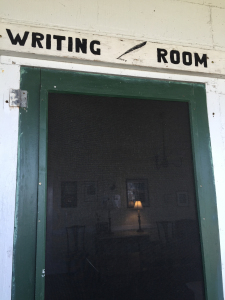

Across the water on Appledore Island, marine labs are operated by Cornell and UNH and Celia Thaxter’s gardens have been revived. I want to go back and see those, as well as sit on the rocks and spend some time in that welcoming writing room at the inn. Or maybe just to look at one the lonelier islands.

August 7, 2015

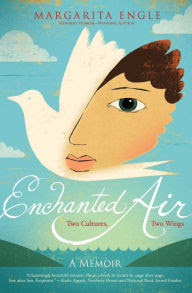

Enchanted Air: Two Cultures, Two Wings a Memoir by Margarita Engle

Flight and sky are images that recur through this verse memoir of the first fourteen years of the author’s life. We see Margarita Engle find a home in Cuba, where her mother was born, and California and Oregon, where she lives most of the time with Mami, her sister, and Dad. Highlights from early years were visits to Cuba, where Margarita’s soul was shaped by the dances and stories of her mother’s family, and the songbirds, bright parrots, orchids, mimosas, and coconut palms that she’s earlier evoked in verse novels including The Surrender Tree and Tropical Secrets. Memories such as of a river that “shimmers like a humming bird/all the dangerous crocodiles/ and gentle manatees/already hidden beneath/quiet water” sustain her as travel restrictions between Cuba and the United States are set. As she becomes a young teenager, the sense of isolation she already felt as a person who loved books and animals more than her peers did deepened due to her questioning and apprehension as she heard newscasts about the Cold War.

Her family is regarded by neighbors with some cruel suspicion, but Margarita finds her own courage as her mother finds hers. They both struggle with homesickness, finding their places between two lands and languages. Neither can forget the island where women work by windows where moths and birds fly in and out, enjoying the fresh air, while also fearing aires, a word that can be “a whoosh/ of refreshing sky-breath, or it can mean/dangerous/spirits.” Fear and love shape the book, along with thoughts on flights of mythical horses and real butterflies. The last poem of Enchanted Air: Two Cultures, Two Wings is titled “Hope,” and a timeline shows public events between Cuba and the United States. One girl’s story shows a joy shared by many as, after so many years, lands that were once friendly can be so again.

Here’s a great interview with Margarita done by verse novelist Holly Thompson at Poetry for Children. Margarita Engle: “I studied botany, and became an agronomist. I remembered family, and became a poet.”

For more Poetry Friday reading please visit Tabatha Yeatts at The Opposite of Indifference.

August 5, 2015

Celebrating Baba Yaga’s Assistant

It was a happy night at the Odyssey Bookshop, with Marika McCoola, who not so long ago directed the children’s department, back to talk about her first book, the graphic novel Baby Yaga’s Assistant. Former colleagues praised Marika’s wit and intelligence and former Simmons classmates and critique group members were excited to see what had come from early drafts. Marika used slides to show us her early notes, some comments from first readers, and how some of these found their way into the final book, which was illustrated by Emily Carroll. We followed the evolution of a sample two-page spread, from thumbnail sketches, then the inks, the black line work and final version. Marika showed places where the illustrator deviated, tweaked, or moved things around for design issues or to give more emotional weight, often expressed with color.

Someone asked why, being an artist, Marika hadn’t illustrated the book herself. She explained that the style she had in mind for the story wasn’t her own, and that as an illustrator she’d also trained as an art director, knowing how to give some directions then be open to what came. Will she illustrate another graphic novel down the line? Possibly. She noted that often her art is three dimensional and multi media, which would mean a lot of sewing and sculpting to make characters for the many scenes a graphic novel requires. She said also that with some emotionally demanding works she wouldn’t want to spend another two years beyond the writing. And she’s simply interested in collaboration and to see what another does with the text. She observed that sometimes Emily Carroll found things in the script she didn’t know were there. At other times the spreads were just what she visualized.

She spoke of liking the graphic novel form, just as she loved picture books since as a child being enchanted with Maurice Sendak’s In The Night Kitchen with its dialogue bubbles. As a teen she adored The Sandman and found everyone reading graphic novels in art school, where she was particularly moved by Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis. Graphic novels, like picture books, bring together Marika’s passion for both words and pictures, often with pictures telling more of the story.

Baba Yaga’s Assistant has been lauded, including a starred review from Kirkus calling it “a magnificent and must read for all fairy tale fans” and an NEIBA book award. I’ve just started reading, but so far love the tests and adventures, the combination of humor, depth, spookiness, realism, and magic.

July 30, 2015

The Art of Revision, and Learning from Harper Lee and Dr. Seuss

These days some students learn about revision in third grade, which is fine as long as it’s presented as the creative fun it can be. I grew up in an age of penmanship classes, being asked to check for spelling, but never to revise. I moved on to crossing out sentences or paragraphs as I completed high school papers, but didn’t really revise until college, when I was writing stories of my own that began as many fragments of scenes. I bought a blue typewriter at a garage sale, and learned to white out words or type over paper slips that were chalky on one side and meant to cover up errant letters. The first word processor my husband and I bought was a marvel, even if its printer sounded like a truck. It opened me to more chances for revision, which I would have resisted if it meant retyping entire pages or chapters. I might never have learned that if you’re only looking at what’s already on the paper, you’re doing revision wrong.

I’m currently revising a collection of narrative verse about girls and science called Finding Wonders. There were lots of drafts before it landed on my editor’s desk, including some in which members of my writing group wrote “Huh?” beside some lines. I cleaned up most of those lines, but a few got through, and my editor wrote things like: “Possible to make your meaning clearer?” The courtesy makes me smile, though I’m also fine with my writing group’s directness: we’ve built trust over twenty-five years. My editor thought the pacing of the first section was a bit slow, and suggested taking out one poem and merging two. But “slow” is not what I want to hear about a beginning, though I’ll never be speedy. So I’ve torn apart the first fifteen pages, to tighten and add small walls my character must bump into or vault. I’ve written some good new lines.

Revision is a major part of my process now, though I wish it had a more glamorous name. I like the “vision” within the word, but that “re,” drags the concept of “again” in a way it’s hard not to see as boring. Of course we’re not exactly beginning here, but there’s an element of its thrill, anxiety, and muscle. There can still be surprises. Revision is sort of like trying on clothes for a big occasion, though maybe you don’t know just what will happen. It’s useless to consider scanning the closet or even laying out the clothes. You must try them all on and see how one choice affects the next. Everything gets pulled out of the closet. We can’t think about details or accessories until we have down the general look.

We also can’t think much about structure and pacing in the abstract. It’s an experience. The time to tidy will come, but you’re not really ready until clothes are piled around your ankles. Then at last it’s time to attend to details. Coco Chanel advised women pulling together outfits to take off one thing before they left their houses, and usually we can find some words to snip.

Revising is not just taking away, but includes making a bigger mess, circling back, cutting and adding. Every time I add to a character, even if I scrape off most of what I layered on, I know her better. Our friendship deepens. I move things on and off a character’s table, and also break some open, turn them around. It’s good to take time for things to reveal themselves as possible metaphors. Just because we made this draft doesn’t mean it doesn’t hold some mystery. We should treat that with tender respect.

Sometimes revising looks a lot like research. I find a few new images and information, and replace with some of the old.

Most writers know this sort of everything-out-of-the-closet revision, turning everything inside out. Recent reviews suggest that “newly discovered” work of Harper Lee and Dr. Seuss seem likely to have been drafts of what would become classics that were set aside. It does seem likely the authors didn’t entirely forget or lose these manuscripts, but used them as maps toward something better. In a New York Times Op-Ed column, Joe Nocera suggests Go Set a Watchman could be an earlier draft of To Kill a Mockingbird, pulled out to make money that the author, now ill and in a nursing home, isn’t asking for. He calls this “one of the epic money grabs in the modern history of American publishing.” For Harper Lee’s beloved classic, working alone and with editor, Tay Hohoff, she may have turned some autobiographical details into the more universal truths of fiction, letting characters take on lives of their own. Joe Nocera quotes Harper Lee from one of her last interviews, speaking of the need to love language, to sit down and work “a good idea into a gem of an idea.” Maybe there’s more to this recently published novel, but it sounds like it doesn’t offer an Atticus or Scout I want to know, or the exquisite sentences in To Kill a Mockingbird.

Another recently found book was featured a few days ago on the cover of the Sunday Book Review. Maria Russo writes about What Pet Should I Get, admiring some lines, but notes its theme of two children surveying a variety of pets and trying to make up their minds is less compelling than other works of Dr. Seuss. She sees this book with the same sibling protagonists as somewhat similar to, but lesser than, One Fish Two Fish Red Fish Blue Fish, “a kind of warm-up for the more freewheeling and imaginatively rich — the slightly more classically Seussian — book.” The backstory to this isn’t as creepy or seemingly lawyer-ridden as that of Harper Lee’s just-published book, and I don’t think readers are as likely to feel betrayed as those who’ve been waiting and hoping for decades for one more book from Harper Lee. The finding of this picture book seems more about going through boxes and pulling up something that perhaps isn’t fabulous, but will do. Comparing the two as Maria Russo does shows another way that revision may be taking the plot and adding a layer, with the author finding and claiming his own truth by deepening his dedication to imagination and whimsy.

Dr. Seuss was famous for revision. He sometimes said it took him nine months, and sometimes eighteen, to write the 236 words of The Cat and the Hat. The variation in months may be due to myth-making, or it may be that few of us count our drafts or can measure the time we spend, as we’re not sitting at a desk for eight hours five days a week. Time gets blurry. But we know the words that can be read fast didn’t come quickly.

Publishers are supposed to be gatekeepers, choosing what’s worthy; at least they tell that to those of us who choose forms of self or partnership publishing. It’s one thing to publish junky books for those who want light summer reading, but to publish less than the best of brilliant writers may lose readers who should be cultivated with trust. Everyone needs to make money, but what matters most is to offer readers books that come from long spells of writing, working with good editors, then taking another look. Every day, every hour, writers might remind ourselves that we may like a page, but that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t throw it away. Something may be good, but there could be a way to make it better.

July 27, 2015

Boston: Children’s Books, Art, and History

I had a great weekend catching up a bit with my daughter, then with former students and colleagues at the Simmons Center for the Study of Children’s Literature Summer Institute. The theme was homecoming. Novelist Elaine Dimopoulos discussed the pull of stories to shape themselves in the form of home-away-home, or perhaps home-away in literature for teens. Laura Vaccaro Seeger spoke of her journal as a home. Both Jack Gantos and M.T. Anderson brought up maps and the tug between what’s known, even boring, and adventure. E. Lockhart (Emily Jenkins) described her itinerant childhood, but called home a place where you keep your books. She also spoke of home as the place you’re making now versus a place you go back to, truth versus nostalgia.

There were discussions of homes that are safe, homes that are not, and complicated homes. Shadra Strickland spoke of illustrating Zetta Elliot’s Bird, and drawing one man based on her uncle. “Every time I drew him, it felt like home.” Illustrating Sunday Shopping by Sally Derby, she was glad to show whimsy and hope, which she said is important to her as a black illustrator, feeling that we need relief from the rhetoric of pain. She showed scenes of cutting paper and pretending, things she did with her grandmother as a child. (In the panel picture above, Shadra Strickland is to the right of Cathryn Mercier, director of the Center of the Study for Children’s Literature, and illustrators David Costello and Hyewon Yum, and to left of moderator Vicky Smith.)

I loved The Crossover, Kwame Alexander’s novel in verse, so it was a thrill to hear him speak, read, and remember. He said that he wrote the book as a love story to his father, after coming to understand the quiet form his father’s love took. His process for the book was to write about 200 pages of story with some line breaks, rhythm, and figurative language: then go back and rework each passage more fully into a poem. He said that in verse novels, neither the verse nor the narrative should be sacrificed to each other.

I spoke about “Beyond Broken Lines: Finding the Lyric Home in Verse Narratives.” The audience was great, and I thank my friend, Deb, for liking what she heard in the morning enough to come again in the afternoon when I repeated the seminar about a “form where writers can say something while hinting that the opposite could have happened, and maybe will happen off the page. Here’s where we are and the road not taken, showing what’s humble and what’s magnificent all in one line.”

There were more thought-provoking talks, ending with Megan Dowd Lambert and Cathryn Mercier, who both put so much brilliant organizing into the weekend, giving a talk that pulled together threads. Then I walked a few blocks to the MFA. The exhibit “Yours Sincerely, John S. Sargent” was in a room with deep red walls and red carpets. I didn’t have the patience that afternoon to peer through glass cases and try to decipher bad handwriting, but I liked the tribute to these newly donated letters, which feature a recurring topic of Sargent’s work and how it should be displayed. I loved seeing photographs of some of his workspaces and sketches alongside finished paintings. Another room is devoted to his oils and watercolors. I picked up “Searching for Sargent,” a guide that shows other of his work in Boston. I admired the murals in the Boston Public Library, up the marble staircase past the grand lions, then walked through the newly renovated section on the other wing. Here is just one shot of the fabulous new Children’s Department.

At the Museum of African American History. I saw the current exhibit, “Freedom Rising: Reading, Writing, and Publishing Black Books.” Glad to see lots of poetry! I went next door to the African Meeting House, recently restored to how it looked in 1855, when notables such as Frederick Douglass and Sojourner Truth preached here against slavery. The meetinghouse was built in 1806 mainly by African American artisans and is now the oldest black church still standing in the United States. A docent relayed the history with a passion as if he’d been in that pulpit long ago, and as if all those pews were filled, instead of just me, taking pictures with my cell phone. I was so grateful.

That conference theme of home stayed with me in John Singer Sargent’s letters to friends and paintings of people in rooms, in the new cozy nooks and full shelves in the big library, and this church where people came to be together, pray, sing, and feel safe in the sometimes dangerous world.