Jeannine Atkins's Blog, page 6

January 14, 2016

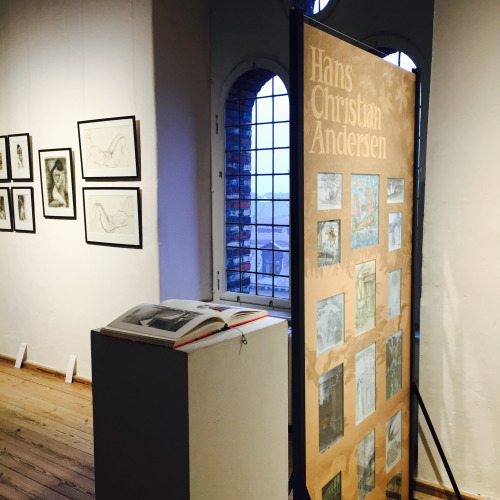

Copenhagen Sights

Last night my daughter and I got back from a few days in Copenhagen, admiring the canals and bright houses, visiting palaces and winter gardens, eating great food, and ever alert for signs of Hans Christian Andersen or mermaids, tin soldiers, little match girls, the emperor with new clothes, red shoes, and wild swans.

We took the train to Helsingør one day to walk around Kronberg Castle, built right by the sea in 1420, which is said to have inspired Shakespeare as his setting for Hamlet. We admired the Great Hall, the biggest in northern Europe, and survived ducking through winding underground halls and dungeons.

We warmed up from the sea winds at a lovely nearby library. This little boy could dip into boxes of books with various royal or medieval themes, while looking out to the water.

Reminders of Hans Christian Andersen, who lived and wrote around the city. abound. He was reported to have stayed at our hotel. When I asked if his rooms were known, a woman at the desk said she didn’t really know that he stayed there, then was quickly interrupted by another who asserted that he certainly did though his room wasn’t known. She said they dedicated a suite on the second floor, as it was unlikely that he would have slept higher, because of fear of getting trapped by a fire. We read that he traveled with a rope in his trunk for quick escapes.

The several statues Emily and I saw were of him alone, as he rejected the idea of being shown surrounded by children, as he did not like to be touched and thought of his stories as being as much for adults as for children: he is right there.

In the oldest part of the city, or Latin Quarter, we climbed the Round Tower, a 17th observatory, the oldest remaining in Europe. In 1716 Tsar Peter of Russia rode his horse up the ramp, and it remains a working observatory with a telescope. Hans Christian Andersen wrote in the library halfway up, where visitors can now get coffee and view art, with an emphasis on children’s book illustration.

Slips of stories are everywhere.

January 7, 2016

Poets & Writers

I’ve read Poets & Writers since I was an undergraduate and aspiring writer, back when it was printed on newsprint and of course entirely black and white. I shared copies with a friend, who years later, when her poetry fell by the way, told me that she kept up her subscription because letting it go would be the final sign that she’d given up on putting writing back into her life.

Since those days, there seem to be a lot more writers in the world and other ways for us to share our hopes, fears, and publication strategies. But I’ve kept up my subscription. This January/February issue is dedicated to Inspiration, but all the issues hold that necessary force. It also remains a good source of information about the writing business. I am happy to have an article called The Missing Locket: An Invitation to Wonder in this issue, which is available in most bookstores. I discuss ways I’m pulled by the gaps in personal and public histories. Sometimes just a little is what we need to begin. I realized this talking to a friend about how I love the show Call the Midwife, but found the memoirs on which it’s based flat: I could see how the show writers developed rich characters from just a few lines. And a few days ago a friend showed me her mother’s diary which she’d inherited. “It’s not really a diary,” she said, and flipping through I saw what she meant. There were copied quotes, taped-in menus and concert programs, and a wonderful few horsehairs, I believe, from a pew where the diarist noted that she’d sat for some years. It all took my breath away with possibility.

This issue of Poets & Writers includes great articles about taking risks, stepping back from marketing, revision, the power of objects, and introductions to debut poets, including Robin Coste Lewis, whose Voyage of the Sable Venus, full as it is with an exploration of history, is a new favorite of mine. In the Editor’s Note, Kevin Larimer reminds us: “Whether thousands, hundreds, or dozens of people might read what we’ve written, or even if we reach just one single soul, we are being given an opportunity to create something bright in all this darkness. Shine.”

January 5, 2016

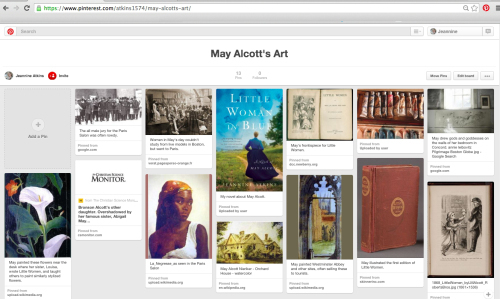

Would May Alcott Like Pinterest?

Reproductions of paintings, photos of places where May Alcott lived, and pictures of people who she inspired or who inspired her, and examples of their work, can now be found on Pinterest, if you click on the link here, or go on anywhere and add my name. I’ve enjoyed giving some slide shows at libraries so people can see May’s work, but for those who can’t attend those, now you can glimpse a bit from your desk. (Though not as much. The generous people at Orchard House kindly gave me permission to take pictures from their collection for slide shows, but not to put on-line.) Big thanks go to writer Melodye Shore giving me a gentle push and a Pinterest tutorial. I’m still learning, and would love to hear from others who post there. Tips? Do you have sites for me to check out? Apparently people sometimes comment right on the boards? That could be interesting.

This was fun, but most of my attention is now moving off May and onto other people from history, though some contemporary characters (often in an attic) are also on my mind. But I remain grateful to all readers of Little Woman in Blue, with special heartfelt thanks to those who pass on word about the novel,which is about to go into a second printing. Exciting, even if the first run was small! Thank you San Francisco Book Review for kind words: “After deep research, Atkins creates a story of a younger sibling living in the shadow of an older, successful sibling many will relate to. … May finds her own way, and it is a fascinating journey.”

December 23, 2015

Layers of Writing

Most of my writing life has been spent at my desk or window seat, and includes long tides of waiting to hear back from editors, and a rare celebratory message that there will be a book. Around a year ago things shifted, so that three of those manuscripts, labored over for years, sent to the desks of many editors, were accepted. Little Woman in Blue was published this fall, with two others coming out next fall and the following spring. This means that I’m working through a lot of layers, moving between promoting one book, seeing another go through the picky process of copy-editing, and doing a revision on another to tighten the pacing and rev up the plot. Those last two tasks were just completed, and I’m stepping away from most of the work of the first.

Recently I opened my computer and whispered, “Hello,” to a girl waiting. Her name in my mouth made me know I was working on the right thing, and I felt so ready to be in her company. I got out old notes and made slashes through some and picked up words and phrases for others, polishing them up. I began to feel back within the rhythm of her life. Someone from history gives me something, and I mean to give her something back. I’ll learn about her life in the same steps forward and steps back that we learn about ourselves. It’s a gentle process that I feel ready for after spending a lot of attention to details such as getting each last word right. I can set down jumbled lines again, even as I arrange clean corners.

But all of the stages include both mess and light. While tightening the plot of Stone Mirrors, I sometimes felt freaked out about the disarray. I’d taken apart poems so they were wildly strewn, back to a different sort of beginning. I knew these parts were on their way to something better, but no one else would, and I had occasional freak-outs that I wouldn’t get a chance to finish and I’d be left with what was worse than where I began. But I made it through this round, and expect more breaking-apart and putting-together and polishing ahead.

Even when a book is finished, the words at last in unalterable place, there’s room for wind to blast through, and that wind is our readers. What will they find there? Little Woman in Blue feels like mine. I can open to pages and remember decisions I made: Why did I begin a chapter where I did, what scenes did I decide to leave out? But it also belongs to readers, and it is gratifying when others care for May Alcott as I do. Not all read her just as I do, or find every sentence or chapters just as it should be. But for many who read, it seems like we have a friend in common. And I’m so grateful.

And now I’m eager to cook, eat, laugh, sing, and generally spend time with my family. I like knitting and reading by the Christmas tree, at some lucky times with the cat on my feet, but I’ll give the characters in my work-in-progress some attention every day. It works best for us all if we meet up every morning: otherwise, they can be stubborn later on. I’ve got a circle of evergreen and winterberries on the outside door, but just put together a wreath for inside. It’s time to trade in glitter and glue for butter and sugar. Good tidings to all!

December 17, 2015

Pushing Characters Off Cliffs

Most writers I know are gentle people. Many are parents, teachers, or others devoted to the care of people and animals. They send wishes for peace at this time of year. But most novels don’t go far if tranquility is at their core. We need to leave our peace-seeking selves behind at the desk when it’s time to stir up conflict.

And this can hurt. Becky Levine recently posted on Facebook about her wrenched stomach and ragged breathing when pushing a character to do something the good person inside her wished he wouldn’t. But was necessary for the story. I’d just had my own revelation that a character was not as lovely as I’d thought, and related to feeling sort of dizzy with dismay, while feeling bound to persevere, after a making pumpkin bread with cranberries. Becky agreed such a break was good, but suggested chocolate chips instead of cranberries. We writers are not just colleagues but allies, and we empathize when our characters go astray. Even as I urged her to let her character stride unblinking into trouble.

Maybe the key here is “letting.” Trying to get more accepting of drama, I began this blog with the image of pushing a character off a cliff, but it’s probably more true to think of it as not standing in the way of a character bound to jump. Really, things aren’t that harrowing in my work in progress, but any misstep even of a conscience can feel that way to cautious me. I began my novel for middle readers wanting a sweet and ordinary girl at the core, and to explore some magic. That’s in place, but as I told a friend, the magic seems to be turning dark. “Magic often does that,” she replied.

So here I am in a forest dimmer than the one I first imagined with a character who’s angrier and has more secrets than I envisioned. I don’t think I shoved or even nudged here there. Did it happen because I had her read The Secret Garden, (something I’m not sure will stay in the finished draft), but perhaps Mary Lennox’s anger was passed along? Or delving deeper into family relationships, did I find myself deeper inside her? Getting to know the girl and her circumstances better, did rough feelings naturally evolve?

Now I no longer have a sweet book and entirely admirable character. I feel the sort of worry and split we do when someone we love does something that we don’t. Usually we can work our way back to love. It’s time for pumpkin bread and tea, getting comfortable with turning lights on and off. Making room, the way my Grandmère’s ceramic angels and my husband’s dinosaurs find a place together.

December 14, 2015

Careful

After years of writing without seeing a book land on shelves, I’m happy to have a new book in the world and two others on their way. But I still have work in earlier stages of progress to tend to. I love the generosity of early drafts, how they offer a place where mistakes are welcome. And I like the word-fixing of final drafts, the excitement of seeing a story head to new readers. I recently sent a book to a copy editor after some dwelling on whether it was okay to write “Ho, gluepots,” instead of “Ho, glue pots.” And making sure that the ten children in a family stuck to their proper ages during the narrative’s course of years. But those drafts in between that are good enough to show someone else, but still mistake-ridden? Well. I was just reminded of how fragile those can be.

Last month I gave some pages to a reader, who was underwhelmed. I shrugged. There are many, many stories, and people have different tastes. I knew some of what I wrote needed fixing, and I was pretty sure I could do that. I put away the notes to tend to other work. But now that’s that done, the manuscript which is not so very far from done was still sitting there. I had another book to work on. But last night when my husband asked, “When am I going to see that book with magic you’re writing?” I said it might not be till summer. I told him I was thinking of working on something else.

But his interest reawakened the interest in me. Only then did I realize the lackluster response hurt more than I showed with my shrugs and qualifications. Our writing is always tender. We have to be careful who we show it to – but still, we need to send it from our desks. Every response can teach us something, and covering our eyes and ears is rarely a good way to learn. We have to seek outside opinions if we want our book to reach others, and it means we have to have a somewhat tough skin. Various forms of rejection are part of this work. Barbs or stumbling blocks can come in many forms, such as ignorance, unkindness, or truth. Sometimes it takes a while to unwind those strands, particularly if they’re tangled.

Spurred by Peter’s kind question, not to mention his tulips, I realized I’d been circling my own manuscript with fear, and had to ask myself why. Sometimes blocked doesn’t look like blocked. We can call it busy. We may turn to another project and call that choice. Maybe it is. But it can pay to take a closer look at what we’ve left in files or drawers.

I hope all of you have someone in your life who will ask, “What’s happening with that book you told me about?” It’s one reason those writing dates, meeting for coffee and complaints, are important: often someone will remind you that they’re waiting and that there’s more than one opinion on a work. It can be wise to look back and consider what happened when we put aside a story we once loved. I get out the index cards, heat up the coffee, and light a pine scented candle. I’m telling myself what I’d tell friends: You can do this.

December 11, 2015

Little Woman in Blue: Out and About

“How is your new book doing?” people sometimes ask. I tell them I don’t really know, beyond that some people are reading, buying, checking it out from libraries, and sometimes kindly posting nice reviews online. Sales records remain obscured for months, partly because books are a business in which stores can order, then return what isn’t sold: so what looks like a sale at first, isn’t really. It’s best not to think about it too much, or obsess about reviews. Once upon a time, back when I started writing, my editor would mail a few photocopies of reviews months after my book came out. It seems like a time of innocence, putting out a book, and writing the next one. I can see more reactions now, sometimes in a matter of minutes if I choose. It can be gratifying, or not.

Books. People like them. People hate them. People won’t pick up every one. As a teacher I know that people don’t read the same book even if the cover and every word inside is identical. But as a writer, I can still be surprised by what people find in what I spent a long time creating. Books and life are full of surprises, and that’s how it should be. The ups, downs, and crooked paths of reality are more interesting than dreams we’ve come up with ourselves, staging all the players and proper responses. Still, I’m grateful for good words in Foreword Review.

And it’s fun to get out and meet readers sometimes. I liked talking recently at Field Memorial Library in Conway. At the Jones Library in Amherst, I gave a talk with slides called Paintings in Parlors about May Alcott and artists she knew, such as her student Daniel Chester French and friend Mary Cassatt. Some artists were in the audience, including Laurie DeVault, who took my picture.

Among other things, I mentioned how May Alcott and women of her era painted on smooth stones, lamp bases, and fans. Afterword, a woman took a fan I offered as swag and told me she’d paint on it; I told her to take a few.

“So I can mess up?” she asked.

“That’s usually part of the process.”

I’ll be talking about Little Woman in Blue next week, Thursday December 17 at 6:30 at the Tilton Library in South Deerfield, MA.

And returning to my love for that short form, I’m teaching a class for MFA students at Pine Manor College in Brookline, MA on Jan. 7 called Using Detail to Structure Picture Books. Information about auditing the class is at this link.

December 9, 2015

Boston Treasures

I just spent two days in the city, visiting my daughter, going to a meeting, seeing the Museum of Fine Arts decked out for the holidays, and getting to a show at the Boston Public Library. I love how the BPL Map Center offers children books and globes as introductions to ways to figure out where they are. The Map Center offers classroom programs that include using historical maps and GIS software so students can compare roadways and housing in the current city to that of the Revolutionary War.

Women in Cartography is their current show. There’s an overview of the role of more than ten thousand women working in the Geographical Informational Systems industry, but I particularly liked examples of work from the 1800s. I saw elaborate and useful charts made by Agnes Sinclair Holbrook, a resident of Hull-House in Chicago, to show immigrant population, income disparity, and mapped information for their mission of reform. I was touched by nineteenth century maps copied by women, when art, and copying it, was often part of a young lady’s education, often to elegant effect. Here is a (deteriorating) globe embroidered by an anonymous girl at a Quaker school in Pennsylvania in the early 1800’s. Girls learned geography and needlework at the same time.

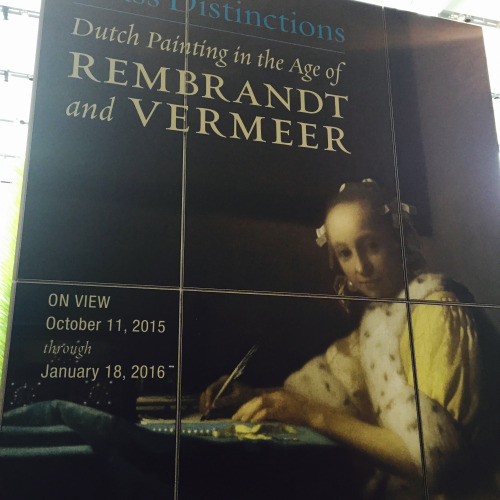

The current exhibit at the MFA is designed to show how people of different classes were depicted in the Netherlands in the 1600s, with galleries featuring the well-to-do, often men in black with white collars that Rembrandt often painted, galleries with views of middle class merchants and other workers, and one room of depictions of those who were barely scraping by. Three tables were arranged for dinner, each under plexiglass. One gleamed with silver and Chinese porcelain on smooth damask, while the others were less shiny, with brass, pewter, stoneware, earthenware, or wood on rough linen. But mostly I gazed at the light in two Vermeers: one of an astronomer and another of a lady writing, with pearls near her paper.

December 7, 2015

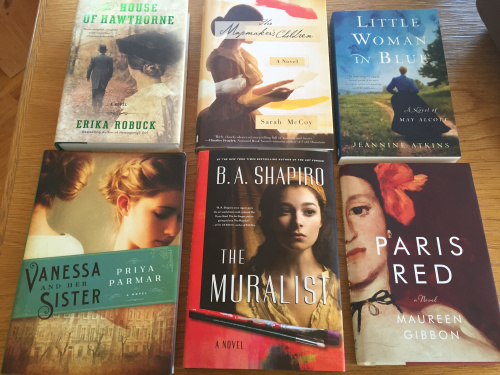

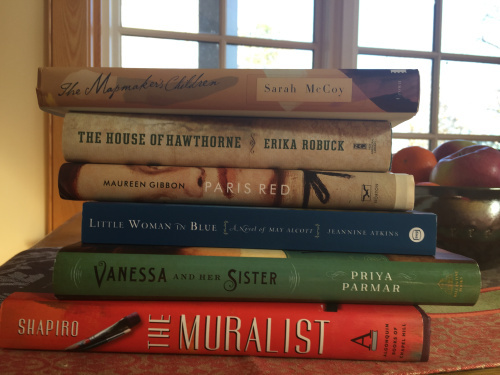

Seven Novels Featuring Women Artists

Many of us enjoyed crayons or paint as children, but artistic confidence often falls away as we grow. Women who continue to pursue art through high school, college, and grad school find themselves ever-increasingly among male colleagues and instructors. According to the fabulous researchers who go by the name Guerrilla Girls, art made by women makes up less than five percent of the holdings of most major museums and most galleries aren’t much better.

If it’s tough for women artists to find respect now, how did they deal with obstacles decades ago? Using fictional devices to develop scenes rich with dialogue and detail, each of the following novels published in 2015 features a real woman who was well known at the time, then mostly forgotten.

In The House of Hawthorne, we meet Sophia Peabody as a young woman with artistic talent that her mother considered a holy gift she feared marriage would destroy. Sophia takes the risk, marrying the handsome author Nathaniel Hawthorne after years of secretly courting. The novel begins in Massachusetts, but excursions are made to Cuba, England, and Italy as author Erika Robuck presents the tensions between Sophia’s allegiance to her paint box and the pleasures and tasks of being a wife and mother.

Sarah Brown, one of the daughters of abolitionist John Brown, lived during the same period as Sophia Hawthorne. The Mapmaker’s Children is a dual narrative with a theme of legacy. One strand features a contemporary woman who’s struggling in her marriage, while the other presents Sarah Brown as an artist with a mission. Author Sarah McCoy created a fictional device of maps hidden within artwork to help former slaves escape on the Underground Railroad.

While Sophia Hawthorne thought of her art as spiritual and some of Sarah Brown’s work was politically motivated, at least two women in Paris during this period were reveling in color or clay, creating art for its own sake. In Rodin’s Lover, Heather Webb conveys the joy the young Camille Claudel found in shaping clay and her conviction that she deserved this pleasure. Auguste Rodin offers sculpting lessons in exchange for Camille’s work mixing plaster, kneading clay, or sweeping floors. Later, Camille not only becomes his lover, but teaches him, too. The tenderness that exists along with passion in her sculptures influences what Rodin puts into his larger bronze figures. Camille’s relationship with Rodin and her own mind grow troubled, then even art, her source of strength, becomes endangered.

Models were important to these sculptors, and in an era before photography was widely used, to many painters, too. Paris Red by Maureen Gibbon begins as a fictional version of Victorine Meurent sketches a cat sleeping in a shop window. Wearing a mended dress and bottle-green boots, Victorine catches the eye of Édouard Manet. She puts away her pencil and tablet, and walks with him past cafés and kiosks, sharing a paper cone of cherries. Victorine soon becomes his model and muse. We see her pose for paintings, take explicitly described breaks on divans, paint, and run errands such as picking up pastels in a shop where she’s drawn to a small box with seven shades of blue, looking like “bits of sky that could fit on my hand.”

Priya Parmar’s Vanessa and her Sister crosses the Channel and moves to the early twentieth century to show the relationship of painter Vanessa Bell and her sister, novelist Virginia Woolf. Told in letters, telegrams, post cards, journal entries, and lists of paints to purchase (British Ink, Polished Silver, and Rose Doré), the novel starts as the sisters settle in the Bloomsbury neighborhood of London, where they spend evenings discussing new styles in art and literature with bohemian neighbors. Vanessa increasingly resents the way Virginia depends on her for care and forever sees her as one of the maternal figures she celebrated in novels such as To the Lighthouse and Mrs. Dalloway. Vanessa works hard to have her paintings displayed with other Post-Impressionists, where they stand out for their domestic imagery as well as their bold colors.

Another driven writer and her artistic sister are featured in Little Woman in Blue: A Novel of May Alcott. Many woman writers remember their dreams taking shape from the portrait Louisa Alcott created in Little Women of an independent young woman wearing an ink-stained smock in a garret. Girls who liked to paint were inspired, too, by the youngest sister. But some wanted to throw the novel across the room after the artistic Amy travels to Europe and upon seeing great art, decides to give up her own attempts and marry. May Alcott, the sister who was the model for this young woman, must have been furious, too. My novel, Little Woman in Blue, shows the determination of the real May Alcott to move beyond what her sister scripted as her future.

The Muralist by B.A. Shapiro brings us closest to our time, with the contemporary story of a researcher at Christie’s Auction House trying to discover the truth of her ancestor, who may have shaped the history of Abstract Expressionism. As in Shapiro’s previous novel, The Art Forger, a woman’s work isn’t given due credit, but instead of a plot involving Degas and the Gardener Museum theft, we read about the fictional character of Alizée who struggles to help relatives move from France to escape the Nazi occupation, while working on murals for the Works Progress Administration as well as her own paintings. Her friends include Mark Rothko, Lee Krasner, Jackson Pollock, and others shaping art in New York just before World War II. Powerful, graceful, and down-to-earth Eleanor Roosevelt puts in an appearance, and it’s fascinating to see the new art through her eyes.

By the early twentieth century, women had won the right to vote, own property, and fill art departments, at least as students. Fashions and paint colors have come and gone: lead white and cadmium red have been taken off shop shelves due to health risks. But these novels ask us to consider what seems eternal about art, romance, marriage, and sisterhood, as well as what seems well past time to change.

December 3, 2015

Crossing Between Worlds

Last night after I talked about Little Woman in Blue at a library, someone told me how she’d carried May with her after closing the covers. She asked, “Do you ever have trouble coming out of that other time and place when you’ve finished writing for the day?”

Writers may have to be immersed so readers can be, and yes, returning to the table under my hands can be awkward. Often a walk helps me cross between the imagined and the real, though sometimes thoughts rise from the woods or people on the street and I’ll go back to my notebook. When asked for the date, I hesitate not just over the day but the year: 1865, say, may seem more familiar even as I hunt down my cell phone and car keys. Part of me imagines the sounds of horses, wagons, sled runners sliding on snow.

Finishing a book makes for another sort of jolt. I don’t expect to ever feel separated from May Alcott, though my book about her is in covers and I don’t expect to write another book about her family. When a chance to see some usually tucked-away artifacts displayed at Orchard House last month, I took it: I could see the bright red in a painting May did of her home in France that I’d only seen reproduced, her sister’s sewing kit, and a fan carried to dances to be autographed along the folds.

It was fun to see the rooms with my friend, Jen, and there was a sweet moment in May’s bedroom, when Iman, the lovely young woman leading our tour, said, “And we have here someone who wrote about May … do you mind me saying that? The woman downstairs told me you wrote the novel I’m reading now!” I got to say a few words about my love for May in the room where she drew gods and goddesses on the wall and perhaps first read Little Women, which her sister wrote across the hallway.

Just yesterday, I wrote my last words on another book about a nineteenth century artist. A revision of Stone Mirrors: A Life in Verse of Sculptor Edmonia Lewis was due to my editor at the end of last month. I attended Thanksgiving dinner, but was glad that my daughter made quinoa with lots of roasted fall vegetables, our friend Jess brought pumpkin soup, my husband made cranberry-apple-raspberry-blueberry sauce and if anyone missed the turkey that might go with that, they didn’t say so, which is sometimes what counts. Thankful. Likewise re the one or two sweaters I’ve been recycling these past few writing-filled weeks. When not focused on my manuscript I wondered how long I could go between washing my hair, and brushed my teeth while opening shades, calculating the time spent on non-writing moves, while hoping to keep my family, friends, and health. All plants stayed alive and I even saw an amaryllis bloom, though like writing, they take their own schedules (and really I hoped for a tardier one on this).

Most excursions involved coffee or yoga or both. But now I’m looking forward to more time remembering that shoulders are good for more than hunching and letting in the fact that there’s another holiday coming up. Laundry will get done. Brown leaves on the geraniums will be plucked. Cookies will be baked, greens will be cut, books will be read, and maybe soon an animal who does more than sleep, purr, and hiss will move into our home.

But to get back to topic – though topic-sticking is something I look forward to taking a break from — yesterday I finished my revision of Stone Mirrors. On my window seat, reading aloud some poems at end to hear the sound, I was weeping for my character, so glad Edmonia Lewis got to where she did, just as if she were living today and I hadn’t spent weeks and years trying to find the best way to end her story. Characters and writers have lives of our own, but sometimes they come together.