Jeannine Atkins's Blog, page 4

June 7, 2016

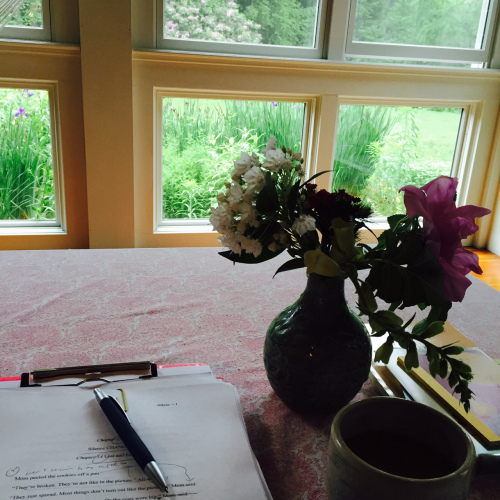

Practicing Acceptance

Walking the dog and on my porch, I’m revising a novel. Watching lots of sentences go, under my hand. Getting frustrated at the new messes I’m making as I’m trying to clean up a draft. There are more squiggly lines and arrows than when I began.

The flowers remind me that perfection is fleeting. Can I enjoy what’s here and not cringe, at least for too long, at what’s leaving and what is yet to be done? Words and blooms must come and go. Trying to write well means lots of lowering of bars. Yoga isn’t all nice postures and Namastes. There’s sweat and straying thoughts and lopsided warrior poses, too.

And when I fail at patience, the dog is always eager for another walk. Where I may be inspired with an idea for another necessary mess-making revision. Or just enjoy bee hum and butterflies zig-zagging over the dirt road. Because it is summer.

June 1, 2016

Crazy Brave by Joy Harjo

The porch today gives me a view of bees and the first hummingbird of the year between star flowers and iris. Our black dog is dozing. I took a break from research to read Crazy Brave, a poetic memoir by Joy Harjo, and am inspired by the way facts and myth, the tangible and spirit, weave together. She writes of the pulls of her ancestors in the Creek Nation in Oklahoma and family struggles that shaped her as a poet. “I was entrusted with carrying voices, songs, and stories to grow and release into the world, to be of assistance and inspiration. These were my responsibility. I am not special. It is this way for everyone. We enter into a family story, and then other stories, based on tribal clans, on tribal towns and nations, lands, countries, planetary systems and universes. Yet we each have our individual soul story to tend.”

Joy Harjo moves chronologically, but divides the sections into east, west, north, south, with each direction having its own tone and spirit. In East, we learn of her years before school, full of a confident and creative connection to the earth and sky. Every day she spoke to the sun. She smelled each crayon before she used it “and felt each color as a friendly field of possibility.” “For me drawing was dreaming on paper.”

We go on to read about how her father’s rage and a pull toward other women that led to her parents’ divorce. She admired him and was afraid of him and found those places came together inside her. Elsewhere she discovered that “the most humble kindnesses made the brightest lights.” When she was eight, her mother gave her an anthology of verse, and found “Poetry was singing on paper.” Some words from William Blake and Emily Dickinson gave shape to her experience. “And to open that book was to disappear into many dream worlds, like the ones I had left behind after I started school …”

A stepfather brought more violence into their home. As a teenager she was glad to escape to the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe, a place that felt like home and she suggests saved her life. The school had been begun by the Bureau of Indian Affairs and run like a military camp, but in 1967 it had been transformed to foster native arts. We read about how she developed as a visual artist and performer, and met the man who’d become her first husband. She gave birth to her first child at eighteen, and another child, fathered by another man, not too long later. He was also unfaithful, and they separated.

Panic increasingly became a part of her life until she had a dream of flying in an attempt to escape a monster. Afterward she wrote a poem reproduced here from her first collection She Had some Horses (1983) that begins: I release you, my beautiful and terrible fear.” She writes of the dream and a poem as a crucial door. “I wanted the intricate and metaphorical language of my ancestors to pass through to my language, my life.” The last pages echo the hope in the book’s first section, East. “the direction of beginnings. When beloved Sun rises, it is an entrance, a door to fresh knowledge.” The memoir’s last line is: “I followed poetry.”

May 19, 2016

Seasons

For most of the springs in my life, I’ve broken lilac branches and brought in bouquets to make a room fragrant while I write. Lilacs don’t bloom for long. Some gardeners don’t want the sort of shapeless shrubs or small trees that may straggle in their yards for the fifty-or-so weeks when they don’t bring purple and fragrance. But why live in New England and not indulge? I also love lilies-of-the-valley, now starting to bloom, which others dislike for the way they spread. Let them.

The month of May is a lovely coming-around to me, but I’m watching my five-month-old puppy see much for the first time. He lifts his nose to smell air or follow bee flight. He stares out the porch window listening to the gaggle of wild turkeys. When I took him for a walk on the first hot day, he flopped on the grass and rolled, momentarily defeated. Then we found a stream, where he nosed into cool ripples. Every dog he smells coming might be his new best friend. He tugs on the leash. Sometimes he’s ignored. Sometimes he gets to touch noses. And every once in a while, yes, here is his new best friend and we humans step back and watch the dogs lunge and twirl into play.

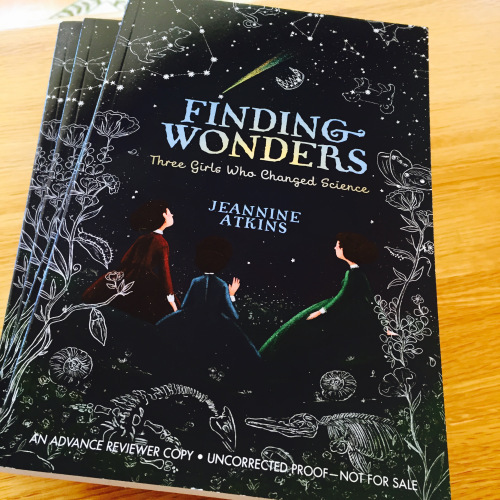

At the table on the porch, I find facts new to me and arrange them in ways that will be new to anyone. I’ve been doing this for much of my life, with the sense of the familiar and fresh blurring. I’m writing now in the wake of some bad writing news to which my husband responded, “Why do you think that manuscript keeps getting turned down?” I felt buoyed by his hint that something was off in the reading, not my attempts over years to shape the work in various ways. And there was some good writing news: a lovely review for Finding Wonders.

The emotions of a writing life, like much that matters, comes in waves. Life has its tides of dejection and lilacs. Sending out work, getting it back, sending it out again. I can’t hold our puppy in my arms any more, but I’m also buying fewer rolls of paper towels and less dazed from lack of sleep. Often I dare to leave shoes on the floor.

It’s good to be awake to what happens then choose where to set our attention. I’m sticking with my husband’s and friends’ faith in my work and enjoying the lilacs while they last. Poetry is made by letting in then weeding out. I choose historic facts from thick books, set some constraints, then nudge the borders, too. I aim to suggest transience, but also what lasts. Every editor won’t ask of a manuscript: Does this matter? But at this table, I try to keep that question alive.

May 11, 2016

Mulberry Leaves and Apple Blossoms

Somewhere or other I’ve seen tallied accounts of all the sights, sounds, and smells an average person might encounter in one day. And our job as humans is to sort them through the enormity, decide what matters, or contend with what seems to mark us whether we wish it would or not. Today I’m working with a to-do list, but while driving I notice trees that make May New England’s the pinkest month. While waiting for an appointment, I take out my laptop. I’m revising, but with one eye on the little girl amusing herself with a straw and her starting-to-get-cranky younger brother, rocked by the mom who’s having a conversation. Ah, that girl is turning the straw into a sword.

Life gives us much to smile about in the moment, even when the general shape of a day or year seems tough. Writing also puts forests of imagery before us, and for a poem, we really have to de-clutter and hone, looking for what will stay in front. Just as a morning is more than our agendas, but what catches us as we proceed, writing a poem means our attention shifts from our first mission to stray words.

I recently spoke to someone about writing poems about real people for Finding Wonders. Sure, I began with biography, but research extended to nature and science books, travel guides, history tomes and more. I write poems because it pushes past biography the way the living are not our work or even our home lives, but what we see and hear, where and when we live. Much of my work begins after I have notes on what made someone famous. I look for what houses looked liked, what people wore or ate. Reading other people’s poetry is part of the process, too, keeping my eyes sharp, my ears open. I accumulate a lot before I sift. Some of what I find may add detail that makes someone seem more alive. Some may shift to metaphor, even ones that shape poems or the book.

Chrysalis: Maria Sibylla Merian and the Secrets of Metamorphosis, Kim Todd’s wonderful biography of the artist and scientist gave me necessary information, including a note that Maria’s uncle worked in a silk mill. Most is lost about Maria’s childhood as the daughter of an artist in 1700’s Germany, but I had to think that this curious girl would visit her uncle at work, and see moths and chrysalises that were unspun to collect their silk, perhaps starting Maria thinking about metamorphosis which she’d later record in paintings that would help change science. I found some brief accounts of silk mills from her time and place, and more extensive nineteenth century manuals written by mill owners in my Massachusetts neighborhood, which established the process wasn’t so different.

Maybe Maria would take her uncle strudel wrapped in linen – what else was eaten for breakfast? Was her hair braided, too? I learned that barefooted children gathered mulberry leaves for the silkworms to eat. I left the crumbly-covered volumes for nature books to look for the shapes of mulberry leaves, the color of berries. This was a lot of reading for about half a poem. But even the many words I left out shape the poem.

Then it’s time to drop off the library books. And this is what I see.

April 25, 2016

What Disappears and What Stays

Write every day, even if just a bit, is advice I’ve been given and give. Writing likes you to show up for at least for a peek. The sentences you compose one day encourage your mind to return to a project more gracefully the next morning. But we should also remember that each day is different. Its tone may need respect.

Saturday night I baked a lemon cake, following the instructions to beat in each of the six eggs at a time and to alternate spilling liquid and dry ingredients before stirring. I made sure the grated orange and lemon peel soaked in the fresh squeezed juice for the requested hour. And I thought of Jane, a friend from childhood who I hadn’t seen in a long time. I’m usually pretty loose about baking directions. What’s the big deal about adding the eggs all at once? But I remembered making cookies with Jane when we were about ten and she insisted on following the cookbook’s instructions to the letter. The idea was that we should at least once try to get things just right.

Jane’s sister had asked me to bring a dessert to the memorial service. Entering the parish hall on a day when the doors could be kept open, I added my cake to a long table of desserts made by other women who knew the woman who’d liked to bake. As I caught up with some old friends, one told me that the house where I’d grown up was gone. “Really?” Yes, others thought that was true, though with the house having been on a hill behind trees, no one had gone to look.

After the service, my husband and I climbed a hill that was shorter than I remembered. I stared at grasses and brush, trying to imagine a house with a big yard and forsythia bushes I used to play under and a stone wall where I set up toy animals.

“You never showed me your old house,” Peter said.

“I guess I just waved my hand as we drove by. I never thought it would be gone.”

The friend and the house haven’t been part of my life for a long time. But nothing is nothing, even dried leaves, grasses, stones, or questions that can’t be answered. Why do I remember the way Jane so diligently followed a recipe that day? Why has so much else disappeared?

Houses, friends, even memories vanish. But important things last, too. That’s what I’ve learned from getting to the age where I sit in a church and squint my not-so-good-eyes at gray-haired strangers for signs of a young person who I might have sung with in the choir with or walked with on the hill behind the church to see the stained glass window and wonder why a velvet curtain covered it in the sanctuary.

Age has also taught me to take gifts where they come. Since there were many desserts, cake was leftover that I was told I should take home. I swept off the wedge before someone else might stop me. I ate some for breakfast, though the sweetness didn’t entirely break my melancholy. And I’m slowly finding my way back to the work waiting for me. Write every day. Yes. And honor the mood of the day. The same person, but not quite the same person, will compose the sentences to come.

April 20, 2016

Writing in Emily Dickinson’s Bedroom

Late snow in Massachusetts shortened the forsythia season and daffodils drooped. But the daffodils that waited for warmer weather to bloom now stand tall. Buds and even blossoms color tips of branches. And on gorgeous yesterday, I got to write in Emily Dickinson’s bedroom. I’m still swooning.

On Teacher Tuesday, the Emily Dickinson Homestead welcomes educators into that quiet second story room as the sun goes down before the lace and velvet framed windows. A few chairs were lined up across from roped-off bed. Docent, author, and my friend Burleigh Muten had invited me to join her as she gave creative prompts to a small group. We’d been welcomed by the staff who seemed as delighted to see us as if we’d come bearing gingerbread, without querying our particular status as teachers or Dickinson devotees. I’ve loved touring the house before, but it was different to be there with just my eyes, not so much listening for stories of nineteenth century customs or responding to people in a tour group. Instead we took more intimate steps toward the poet who spent so much of her life in this house on Main Street in Amherst.

Burleigh gave writing prompts that related to Emily Dickinson’s work. Some participants read some of what we wrote there, some just listened, and one chose even not to write but to just sit in that room, watching the light fall on a small desk of the sort that Burleigh told us was often used for sewing. Weighing less than a big pumpkin, the desk could be carried from one window to another for the warmth or better light. I wrote some lines related to my current novel as well as this:

This is no kitchen with spilled molasses,

cinnamon, and conversation.

Silent light divides the folded paper

on the slanting plane of the desktop

with no room for swinging elbows.

Words are measured like stitches:

not much larger than a needle, no wider than a thimble.

And then she looks back at the sky.

April 18, 2016

Reaching For, Failing to Grasp, the Perfect Book

A few nights ago I met a friend for soup, sandwiches, and an amazing lemon crepe before we headed to a poetry reading. “How is your writing going?” I asked Naila, who replied that her novel had a plot and plenty of words but some music was lacking. She said she felt stuck, remembering other peoples’ great novels that seemed to have sung and stuck with her.

The next night I picked up In Other Words by Jhumpa Lahiri, which is about learning to write in Italian, a language she didn’t grow up with, and how that meant accepting imperfection. She quotes Carlos Fuentes: “It’s extremely useful to know that there are certain heights one will never be able to reach.” Jhumpa Lahiri writes about working in a language she’ll never get right, managing the anxiety that creates, and how awareness of impossibility is part of the creative impulse because it makes you marvel, which is one reason we write books. She talks about this in an NPR interview, too. “It’s an ideal that I’m moving toward. You know, the closer you get, the farther away it gets. But I think, isn’t that the point of creativity, to keep searching?”

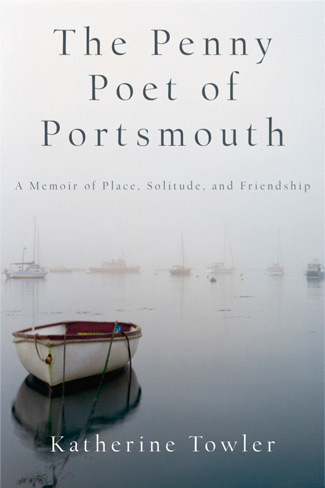

Now I’m reading Katherine Towler’s lovely The Penny Poet of Portsmouth: A Memoir of Place, Solitude, and Friendship, which is partly an account of the last years of a poet who was her neighbor and an account of her own writing process, which means moving between solitude and company, rare satisfaction with her work and trying again. Katherine Towler tells of often looking out a pond that changes with the tides, and is beautiful whether it’s water or mud flats. Early in the book, the poet of the title, Robert Dunn, asks her, as I asked Naila, “How is your writing going?” And when she expresses frustration with how long it takes, though she knows herself as a slow writer, he counsels that whatever the writer tries or wants, the writing takes its own time.

Work in progress can seem like that tidal pond, coming and going, but it can be hard for us to see it as beautiful in all its guises, as Katherine Towler saw the mud and water. She calls the process of writing a novel “a step forward and a step back, rewriting the same scenes over and over until I made myself believe them.” Finding a place between where we are and where we want to be, between anxiety and marveling: that is our task.

April 11, 2016

Cloth Lullaby: The Woven Life of Louise Bourgeois

Using a river in France as a frame, this picture book by Amy Novesky shows how artist Louise Bourgeois grew up helping with the family textile business, then made art until she died in 2010 at age 98. I love reading picture book biographies of strong women, but what makes this stand out is the way the not totally linear plot grows from the strength Louise got from her mother, as well as lessons in craft, form, and color. Like her mother before her, Louise’s mother repaired tapestries. Louise began this work at twelve, drawing in parts of the pictures that had worn away. Since tapestries got most worn at the bottom, she “became adept at drawing feet.”

The book quotes her as writing: “My childhood has never lost its magic, it has never lost its mystery, and it has never lost its drama.” The text conveys all of this. A focus is on spiders, who not only work with threads as Louise and her mother did but gave them a philosophy: if webs get broken, spiders weave and mend.

Louise studied mathematics at the university in Paris, but after her mother’s death turned to painting, weaving, and sculpting giant spiders from bronze, steel, and marble. She created cloth people, books, and spiders from old clothes she cut and changed.

The story is quiet and deep as the beautiful river painted by Isabelle Arsenault, its blue reflected in the endpapers. It’s a soothing and sometimes sad book, with careful words and the artist’s rendition, using a red, black, and indigo palette, of the imaginative way Louise sees the world from early on. I’ve read Cloth Lullaby several times the way I come back to poems, and each time the book inspires me with both a sense of possibility and of how the past weaves into the background, but is never gone.

Amy Novesky’s other picture books about women artists include Imogen, Georgia in Hawaii, Me, Frida, and Mister and Lady Day. Isabelle Arsenault’s work includes illustration of books about Virginia Woolf and Emily Dickinson.

April 7, 2016

The Marketer Dreams of the Window Seat

It’s a dream come true to have published a novel last fall and to have books coming out this fall and next spring. From the outside it may look like I’ve had a few prolific years. Really, these three volumes represent more than a decade of slowly writing and patiently-as-possible submitting and fielding rejected manuscripts, until at last they found the right editors at the right places at the right time.

I liked talking and writing about the Alcott sisters and other women who’ve enriched my life to interested readers, sometimes getting a little more dressed up than I do for a day on the window seat. Marketing brought a small sense of power that came from taking the fate of my work in my own hands. I’m grateful for help finding lovely hosts who gave me opportunities to speak or write about my research and fiction.

But there’s also something to be said for long stretches of quiet in which to mull. For the past few months I’ve been glad to spend less time nudging a book toward readers and more time shuffling new words in my computer. Writers dream of publishing day, but when it happens, we might either be disappointed that the lights weren’t as dazzling as we’d imagined or realize how accustomed we’d gotten to the dark. I often wondered if I was waving my book in peoples’ face too much. Yes. Was I doing enough to get my book in front of potential readers? No. Was I showing enough gratitude to readers and kind strangers who blog or talk up books? No, how can there be enough?

I’m hardly alone with my ambivalence about marketing. Mention the word to many authors – often introverts like me — and you’re likely to see faces twitch. Google “marketing” and you won’t find deathless or even imaginative prose. Writers who are marketers have to decide how much effort to put into blowing small horns and how much to trust to publishing fates. There’s no clear formula for balancing the work of tending to sales and the needs of new words. It’s a world if not of spread sheets then to-do lists, which are never-ending. Like say puppy-training, gardening, or housework, lists loop around more than reach an end. (Though puppies, plants, and books give back more than kitchen counters.) The things we can cross off lists aren’t usually the important things.

Marketing aims for ever-rising numbers, making a climate of never-enough. Every small success pushes up expectations. We can cheer for sales, but if we let ourselves check rankings, perhaps and usually obsessively, we’re bound to see them dwindle. It can be as unnecessarily dismal as peeking behind the scenes of a butcher shop. Learning sales information brings thrills, disappointments, and attempts to stay sane, for with every book sighting, a greedy little voice may whisper: Hey, but why aren’t there more? I remembered that Buddhist hungry ghost with its unending appetite, fairy tales about the king whose touch turned everything terribly to gold, curses disguised as charms, and adages and advice about being careful what you wish for. The chant of never-enough isn’t a good music to create from. That needs a place of trying to feel settled where we are.

Book marketing is a game with no winners or clear stop signs. The novel I already gave a lot to, and love, still needs me. But too much attention to sales is like focusing on the wedding dresses and cake and not the marriage. Marketing means being busy, while creative writing is about allowing in idleness. A marketer has an end in mind, while when I write fiction or poems, I’m more attentive to the surprises of the present than goals.

We publish partly because there is a need to call something finished, and that’s marked in a festive way by finding readers. We make publicity efforts because selling books gives us a chance to publish more. It’s a circle, just like day to night, and just like that, we need the dark murk of creativity at least as much as we need to put our work on shelves.

Recently, I’ve spent less time with my eye on the very small crowd and more time looking inside. I swapped reading short forms on the Internet to reading longer books on my lap. I stepped away from the not so very bright lights to spend more time in the dark, spent less time reaching out and more time reaching in toward a first draft with all its mess and forgiveness. I wrote fewer blogs that I hope don’t sound too much like begging or bragging, and drafted a novel, with wide margins or many pages that not only allows but grows from mistakes. I shifted my attention from smooth surfaces to craft wrong ways where new things can happen.

I like having people read what I wrote, but that’s never been the whole reason I write. I chose this work partly because when I’m composing something new I feel more alert to the beauty of people, dogs, trees, and clouds I find along my way. Everything seems brighter. We have to dig in earth as well as set nicely cut vegetables on the table. Writers need to wear old clothes, not dress with an eye on the mirror. A time comes to leave baseball metaphors with their pitches, hits, misses. and scores. To spend less time fixing words and more time writing wrong ones, leaving lists and letters and getting back to the big space of a book. I need the closed room necessary for creation, to reenter the land of wrong turns.

Of course the marketer-in-me will be back soon enough. For now I’m enjoying time just with the raw page before getting back to peddling stories and verse I believe in, while trying to muster some grace.

March 28, 2016

Picture Books about Women in Science

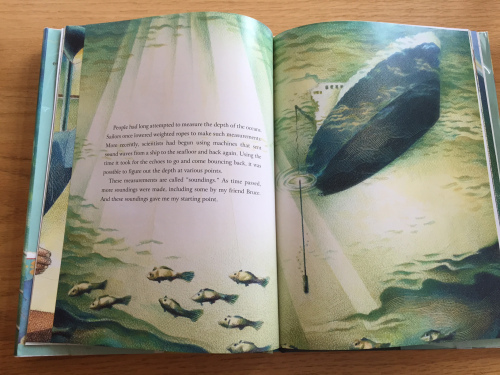

Like many picture book biographies, two recently published picture books about women in science begin with childhood stories that suggest a future course. Solving the Puzzle Under the Sea: Marie Tharp Maps the Ocean is told in first person as if the scientist is looking back over her productive life. Marie is shown helping her father make maps showing soil conditions for farmers, work that kept the family moving a lot, though never near the sea. The book by Robert Burleigh continues with a summary of Marie’s college years studying geology, a nod to the discrimination she faced as a woman looking for work in science, and a celebration of her persistence. (Not mentioned here is the reason that finding work at all was made possible was because she sought a position during the WWII years, when men joining the armed forces had left spots that were filled in by women such as her.) Marie is shown working with Bruce Heezen, her most important colleague, using soundings to find depths in parts of the ocean and making charts to compare them. This led to the discovery of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, which helped prove the earth moves and support the theory of continental drift.

Raúl Colón’s watercolor and pencil illustrations, with lots of blues and greens, are gorgeous. The book includes a glossary, bibliography, and “Things to Wonder About and Do.”

Original and lively perspectives were rendered with pencil by April Chu for Ada Byron Lovelace and the Thinking Machine by Laurie Wallmark. The story is told in a simple but delightfully exuberant style, beginning with a baby born to a mathematician and a more famous father, the poet Lord Byron. A scandal is referred to, and the mother takes away the baby who will never again see her father. Ada grows up loving invention and numbers. When she contracts measles that leave her temporarily blind and paralyzed, her mother provides plenty of mathematical exercises to keep her busy as she recuperates.

As a young adult, Ada finds generous and intelligent mentors in Mary Somerville and Charles Babbage. When Babbage shows her his idea for a mechanical computer, Ada works out an algorithm for him to follow, making the world’s first computer program. Sadly, she never got to see the program run, but her work inspired others, and her name today is honored in ways such as Ada Lovelace Day, which celebrates women in STEM.

The book has a timeline, a bibliography, and an extensive Author’s Note.