Jeannine Atkins's Blog, page 5

March 21, 2016

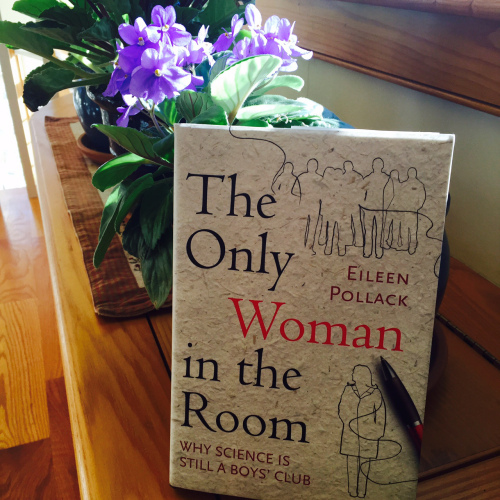

The Only Woman in the Room: Why Science is Still a Boy’s Club

The Only Woman in the Room by Eileen Pollack is a blend of research and a often poignant account of her early interest in math and science, her work as one of the first two women to earn a Bachelor of Science degree in physics at Yale in the 1970’s, and the circumstances under which she decided to change her focus on science to literature. She values her present life writing and teaching creative writing at the University of Michigan, but her grief for what she left behind is palpable. As she describes her joy in asking questions about the nature of the universe, and an ease with mechanical things – she recounts her father’s directive to fix her own toilet -– we also feel the loss.

The book expands upon Eileen Pollack’s important New York Times article, Why are There Still so Few Women in Science? I read this 2013 article while writing Finding Wonders: Three Girls Who Changed Science, a book for readers ten and up that will be published this fall. Pollack’s notes about the need for girls to have role models, and particularly to see how women managed to balance careers with other aspects of life, were affirming. If you lack time to read this great article at the moment, you might at least check out the stunning photo of a 1927 physics conference where Marie Curie is the only woman in attendance.

While Eileen Pollack often felt alone or at least in the minority as a female in science classes, she uncovers research that highlights how she was one of many who showed an interest and strength in science, but left their fields. Often this was less about talent – she meets plenty of men who don’t let poor grades stop them – but because they felt discouraged or dismissed. As a writer, mentors praise her, but not in science classes, where she performs equally well. Some men dismiss the wanting of validation as a weakness. But why should a need for one’s successes to be seen be called that? What’s wrong with wanting to feel good about your work and part of a community?

She describes how boys tend to be raised to be more confident, while girls are expected to be modest, which can tend to make them see themselves as less intelligent than their classmates when they’re not. Even one person who believes in you can make a difference. Again, I found this with my research on Maria Sibylla Merian, Mary Anning, and Maria Mitchell for Finding Wonders: all had fathers who encouraged and were proud of their daughters’ success.

In the 1800s, astronomer Maria Mitchell wrote: “science needs women.” Eileen Pollack demonstrates how this is still the case, and notes how a woman’s presence in a laboratory can shift values so that not only women but men feel it’s all right to stay home with a sick child or take off an afternoon to attend a child’s recital, game or event. When Marie Curie ran her Radium Institute, she insisted on breaks for exercise and fresh air.

This book’s core is Eileen Pollack’s own story, which she narrates in fascinating detail. She’s honest about events and her responses, which are sometimes sad, but she cites hope for change and brings in humor, with chapters titled, “Science Unfair,” “Freshman Disorientation,” and “The Women Who Don’t Give a Crap.” She includes research and interviews former teachers and classmates as well as those studying and teaching now. There are some differences, but not enough. When she goes to Yale to speak about women’s role in science, the then chair of the Department of Physics expects only a few students to attend her talk, as certainly struggles from decades back are less relevant today. But the hall fills, and Meg Urry clears her full calendar to discuss the issues further. Women in science still struggle with issues different from those facing men. Reading this book is a step forward.

March 14, 2016

Seven Reasons to Know May Alcott

History may be most intriguing when we look past selected stars to the constellations of people who made up the daily lives of the famous. As my friends know, I’ve been obsessed with Louisa May Alcott since I first read Little Women. As an adult, I grew curious about her friends and family, particularly the youngest sister in that novel. In real life, was May really such an affected niminy-piminy chit as her sister depicted? Not at all. And how did May feel about Louisa describing a young woman, whose name she rearranged into Amy, as “a commonplace dauber” who gave up art in order to marry the writer’s cast-off beau? I wrote Little Woman in Blue: A Novel of May Alcott, to answer that question and more.

In the mid-nineteenth century, many prominent citizens of Concord, Massachusetts cared much more about language than color and form. I admired the way May kept painting in a time and place that didn’t have much use for art. During Women’s History Month, which gives us a chance to celebrate those who were overlooked, here are seven more reasons why everyone should know about this woman born 175 years ago.

# 1 Louisa May Alcott was her sister and rival.

For more years than most who’ve read Little Women would guess, Louisa and May were both single women working outside the home, bonding over their desire for fame and fortune. How did May respond when her sister, at age thirty-five, and after about twenty years of professional writing, won the acclaim and money they both craved? There’s a lot to that story, including a little treachery, but I’ll just say here that May showed a good amount of grace.

# 2 Henry David Thoreau taught May to observe closely.

Before Henry David Thoreau built and moved into his cabin at Walden Pond, he was a teacher. His lessons included not just reading and writing, but walks in woods and meadows. The Alcott children were among his students. May likely was inspired by his insistence on long quiet observation, necessary for both naturalists and artists.

# 3 Nathaniel and Sophia Hawthorne were May’s neighbors.

When the Alcott family lived in Orchard House in the 1860’s, the Hawthornes lived next door. May might have had her fill of writers, but she was interested in Sophia’s paintings. She knew that Sophia worked much less after marrying Nathaniel and bowed to her husband’s belief that it was unseemly for a wife to sell her work. May must have watched the ways that Sophia both managed and failed to find a balance between making art, helping a husband who adored her, and raising children, one of whom would court May.

The Hawthorne’s only son may have been a model for the boy next door in Little Women. Like Laurie, Julian was handsome, spoiled, lazy, and charming. His family wasn’t as wealthy, but when the Hawthornes returned from years spent in Europe to move back into the house next door to the Alcotts, they brought an air of sophistication, as well as marble for the mantelpieces. We can’t know exactly what passed between May and Julian during the years of their off-and-on flirtations, but Julian’s memoirs, which include an episode of rowing at dawn to watch lilies open on the Concord River, make it clear he never forgot her.

# 4 May taught one of the country’s most admired sculptors.

Daniel Chester French was a ho-hum student at MIT when his hopeful father, noting his son’s talent for carving parsnips and sculpting snow, asked May if she’d give him a few art lessons. May taught Dan techniques such as how to make armatures from pipes and wires to hold up slick clay. When the town of Concord wanted a statue of a minuteman for the river, Dan was asked, though he was still in his mid-twenties and had no particular experience. He also worked for free. Since models weren’t available in the small town, Dan borrowed a long mirror and a statue of Apollo from the Boston Athenaeum to complete his work that many admire near the Concord River.

After sculpting that bronze sculpture, he’d go on to create hundreds more statues, including the large marble tribute to a president in Washington D.C.’s Lincoln Memorial. He built that in Chesterwood, his home in the Berkshires, which is now open to the public and displays his tribute to May.

#5 May was an acclaimed copyist of J. M. W. Turner.

Turner’s landscapes and seascapes helped May see the natural world as dynamic, and showed her a way to paint with looser strokes. While living in London in the 1870’s, she got a pass to work in a room in the National Gallery where Turner’s watercolors were kept in long drawers to protect them from light and moisture. A caretaker took out these one a time for May and other copyists who painted at a long table, then sold their work to tourists.

The copies she made were admired by John Ruskin, one of the most influential art critics of the day, who’d helped manage the care and placement of Turner’s over 19,000 paintings and drawings after the artist’s death. May likely admired the way Ruskin’s vision of the function of art extended beyond the pleasure or meaning to be found in galleries and museums. He wrote: “There is no wealth but Life. Life, including all its powers of love, of joy, and of admiration.”

# 6 May was a friend of Mary Cassatt.

Mary Cassatt’s father, a successful Philadelphia businessman, thought Paris was no place for a woman to live alone, so Mary suggested he, her mother, and sister come live with her. Paris was the only place she could paint. The family shared an apartment and expenses, though sales of Mary’s paintings paid for her studio.

May Alcott and Mary Cassatt bonded as two single American women in their thirties painting in Paris. They met at the Cassatt’s Thursday teas, visited galleries together, and rode horse-pulled carriages through the parks. There’s no record of their conversations, though we might assume topics were much like that of other women artists: bold colors, brands of paints, reviews that missed the mark, babies, macarons, death, and love.

Statistics from the National Museum of Women in the Arts show it’s still hard for women to achieve recognition. Friendships help.

# 7 May had the courage to paint even if she didn’t create a masterpiece.

May was a good, though not great artist, which feels especially refreshing when seen from a culture obsessed with achievement over progress or happiness. May kept making art though she won few awards, and taught others. She painted to see the world more clearly.

Of course I can find at least twice as many reasons to know May Alcott, and the historical record can’t answer everything. You’ll find the novelist’s view I brought to these relationships in Little Woman in Blue. Many thanks to those of you who’ve read it!

March 9, 2016

Wardrobes, Tornadoes, and Rabbit Holes

We’re told that children nowadays don’t have wide or steady attention spans. And that a novel’s first page should offer up drama, a setting, a sense of the main characters, and a question that will keep us reading. Did authors in the past have more time to coax readers into stories?

Perhaps some did, but yesterday a student in my children’s literature class pointed out that one reason some movies based on classics seem better to him than the books is because some novels for middle readers sprint at the outpost. We just read The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, where he pointed out that the four children are swept from London and their parents to an old house in the country in the first paragraph, and four pages later, Lucy is opening a wardrobe door.

He also mentioned Alice in Wonderland, where Alice goes from reading on a lawn down the rabbit hole in the fourth paragraph.

And the first spoken line in The Wonderful Wizard of Oz is, “There’s a cyclone coming, Em.” Four short pages in, Dorothy and a house are whisked off on the wind. We don’t get time to know these characters and their homes before they leave them.

All of these books have some roots in fairy tales, which are famous for fast action and compressed time. But none really employ the sort of characterization and build up of detail that we’re accustomed to in either more contemporary novels or movies.

Maybe children today are challenged to pay attention, but literature suggests that this could have long been so. Are these swift beginnings good ones? Or is it best to borrow some of the fast pace – as E.B. White does with the first line in Charlotte’s Web – “Where’s Pa going with that ax?” – but goes on to have breakfast table conversation that more leisurely develops the characters, time, and place.

March 1, 2016

Hands

In the parking lot outside of Whole Foods, I ran into a friend who recently retired from teaching. She told me how she writes poetry in the morning, and, waving her hands, told me that the rest of the day is devoted to errands, cooking, and caring for things at her home. She misses much at the university, but she said she was glad to have more time for working with food and flowers, doing things with her hands.

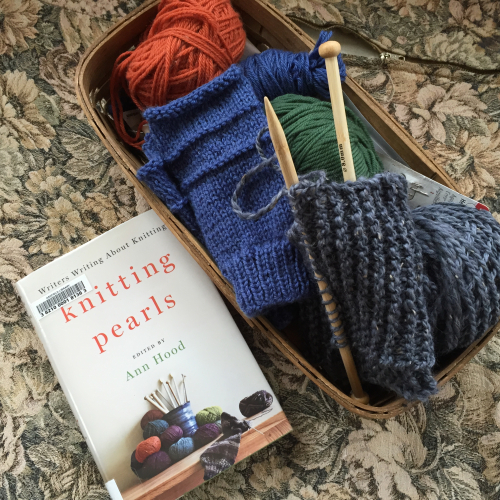

I suppose we’re all looking for balance, whether or not we care to use that word. I love Ann Hood’s fiction, and am enjoying these essays she collected from other novelists about the role that indulging in texture and color, focusing on something besides sentences, plays in their lives. I’m just a beginner, and while I admire others’ creations, don’t aspire to be much more than a knitter of scarves and fingerless gloves. I just want some down time with pretty yarn, and am okay with knit-knit-knit on big bamboo needles.

I was also soothed by reports in Knitting Pearls of the role that unraveling and starting over plays. The theme kept coming up of how knitters and writers resist it. Beginning knitters go to teachers to unravel for them. Then there’s the tricky business of finding a new place to start. In the earlier collection, Knitting Yarns, Ann Patchett writes of being a young woman in Ireland and England and approaching strangers, holding out her somewhat tangled work for help, which was always given. It’s good to be reminded of the necessity of starting over and all the possibilities it offers in essays by favorite writers like Barbara Kingsolver, Jane Smiley, Elizabeth Berg, Anita Shreve, all bringing their great prose to the subject of knitting.

And remember that much is easier to start than to finish. Maybe I didn’t need a reminder, but returning to my old baskets to pull out scarves with less than a fistful of yarn to use up, one fingerless glove and half of another pair, reminds me how it’s good to stick the course. And if I keep going, I may remember how to bind off, which used to scare me, but now I see is fun. It’s astonishing to finish something you spent days with, whether word by word or stitch by stich. I’m seeing the end of a revision of a revision of a revision, times many, and just sewed buttons on a scarf that took less time, with a few imperfect knits (I miss the delete button.) Here it is on me with eleven-week-old Kirby, another reminder that progress is rarely straight forward, but well worth every step ahead or back or to the side. I’m hoping to curb his taste for footwear, but for now have learned to keep one foot on the empty shoe while putting on the other.

February 22, 2016

Puppies and Revision

We’ve had Kirby with us for nine days now, and in that time he’s lost his squishiness and gotten serious about growing long legs. He’s learned his name, how to bark, is working on what should happen inside a house and what outside, and understands and is respectful of the cat’s boundaries. He’s excited about getting to know the world beyond the yard. He’ll start puppy classes next week and I hope he’ll learn, as toddlers must, that 3 a.m. is not a preferred time to play. Yes, he’ll learn. He wants to please and loves us, as we do him, though there are of course those normal puppy pulls toward trouble.

Besides opening and closing the door a lot, I’ve loved having a companion as I write. A few weeks ago, I took a break from my novel to look at a manuscript turned down, albeit with compliments, five years ago. I’d remembered it fondly, but when I gave it a new look, saw it needed more than dusting. I changed the main character’s age, so must create lots of new dialogue, and lopped off a major plot thread to bring out the bones. Which let new ideas slip in. What I thought might take a few days when I first brought the manuscript back into daylight, is taking weeks, but feels well worth it. Much is getting trimmed and more being rewritten, but there’s still a basic trust of the people and place I can lean on, and make me feel sure enough of my scissors and pen. And I’ve learned some things in five years, which I can put to use. Hurrah for second, or multiple, chances. And patience.

February 15, 2016

Companion, Distraction, and Cuteness

Multi tasking today, revising a manuscript while teaching the new puppy not to eat it. Kirby is not only a sweet rescue lab mix, but at not quite three months, a smart one. He’s catching on to bathroom manners pretty quickly, though it means taking him out in the cold, and now snow, every hour or so.

He keeps a respectful distance from the cat, who I think misses our old dog, but has not been welcoming. Kirby is learning not to chew computers, power cords, and paper. When he’s not looking for trouble, which is puppy nature, he’s a great side-snuggler as I work.

I read about house training with a crate and over the years we’ve done it for several dogs. Still, late last night I wasn’t sure how best to proceed, when Kirby plunked himself in the laundry basket in the bedroom and seemed reluctant to come out. He stayed there till almost morning. A reminder, now that I’m back at the keyboard, that I’m not the only one with ideas. Even as I revise with most threads in place, it’s good to sit back sometimes, watch the world, and let a story follow its own mysterious course. I’ve also got to think about each sentence under my hands as well as the book as a whole. Which is sort of like giving a puppy what he needs, while not forgetting about the sort of dog you hope he’ll become.

And then get back to admiring the cuteness.

February 8, 2016

Why I’m Writing Today

Every day, writers need fresh motivation. Every day, what gets us to pick up a pen, or move from checking the Web to facing a blank file, may look a little different. I’m pretty happy with the beginning and the end of my novel in progress. That’s a nudge, as I don’t want those chapters to go the way of other unseen files. I have to straighten out, or probably make wigglier, the middle, as a beginning and end can’t make a book. It’s not like making a nice appetizer and heading straight to dessert. Readers really need a middle.

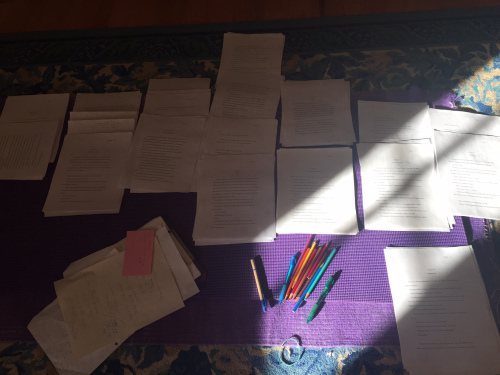

I’ve looked forward to colored index cards and pencils, and today I got to use them. After a bit more fiddling on my computer. But I started racing to get my chapters out in time to enjoy the sun while I did some editing yoga. Then I had to keep working, rather than wreck my arrangements, so I could do actual yoga on that mat: more than doing child pose while scribbling notes in margins. But as long as I’m down on my knees, I see a few flaws to chop or dust. Is that the edge of a theme peeking out? I pull the thread. Great. Except that this means cutting and rearranging more scenes to make a place for an expanded theme.

Then I offered myself a nap. And came up with three sentences while waiting for some short sleep. Then another cup of tea and back to work. One sentence led to another. A paragraph got tidier. A scene found a new place. I think the plot is missing. But I’ll keep an eye out for it while shoving trailing ideas into place, arranging sentences one by one, page by page, tomorrow. And plot hunting can happen while reading, daydreaming, or even dreaming. Oh, tomorrow. When the sun will stay out just a bit longer, a pleasure I’ll try to bring into the work.

February 1, 2016

Picture Books: Finding Beauty on City Streets

E.B White considered Stuart Little’s search for the lovely bird Margalo a quest that “symbolizes the continuing journey that everybody takes — in search of what is perfect and unattainable. This is perhaps too elusive an idea to put into a book for children, but I put it in anyway.” E.B. White often wrote about finding beauty and wonder where it wasn’t expected. Charlotte’s Web wouldn’t have the same glimmer without the manure piles and we’re reminded that its hero, such a generous and wise writer, is also bloodthirsty. Charlotte can’t help it, but she has a taste for flies.

Picture books also take on the theme of keeping a clear eye out for beauty. There was a lot of excitement in our children’s book circles when Last Stop on Market Street recently won the Newbery Award, whose shiny stickers are most often placed on novels, deeming the words the most distinguished of the year. The picture book by Matt de la Peña is about a boy learning to see the beauty around him in a rundown neighborhood depicted in collage, acrylics, and “a bit of digital manipulation” by Christian Robinson, who was also honored by the ALA for his art. Buildings look dilapidated. People aren’t dressed in the height of fashion. But the boy’s Nana, whose wisdom might come from the church we see the two leave at the beginning, offers leading questions to prompt him to second or deeper glances. A change comes when CJ hears a man playing music on the bus, with his delight shown in a joyful two-page spread. Still, after passing “Crumbling sidewalks and broken-down doors, graffiti-tagged windows and boarded-up stores,” Nana must point out a rainbow arcing over the soup kitchen, where the child becomes helper and friend.

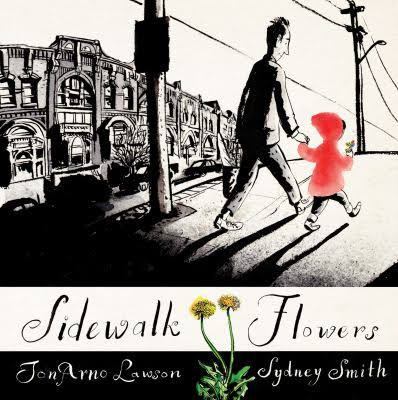

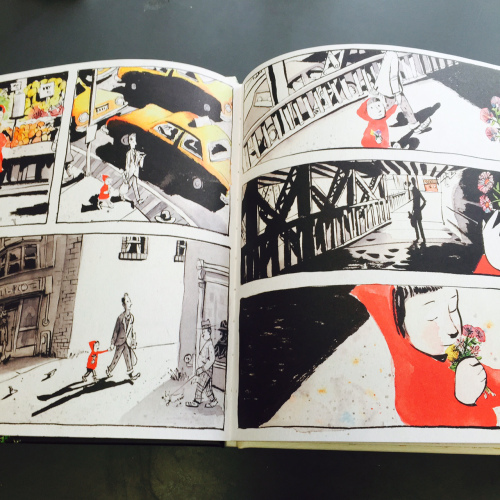

In hero’s journey terms, Nana is the guide toward this change, while in another picture book published in 2015, a little girl in a red-hooded cloak walks with her father, who’s often on his cell phone, staying in the center of her own journey. In Sidewalk Flowers, a girl finds flowers in the cracks of sidewalks or where others might see weeds in a city that looks generally bleak, even in the park with its leafless trees. I’ve “read” wordless picture books before, but I believe this is the first one where an author is credited. Apparently Jon Arno Lawson envisioned the story and sequence of images done in graphic novel form by Sydney Smith, often black and white except for the girl’s cloak at the beginning, where we see birds.

After she leaves flowers to honor a dead bird, the city is shown more often in color, as if to suggest that acknowledging what’s hard can let one see more. The girl also gets closer to home, and her father puts away his cell phone. She bestows flowers to her mother, brother, and sister, and finally herself, looking up at more birds in a big sky.

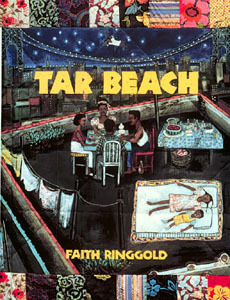

One of my favorite books on this theme is Tar Beach, the first book for children written and illustrated by Faith Ringgold, who won a Caldecott Honor in 1992 for this and went on to create more than a dozen more books for children. These acrylic paintings were based on one of her story quilts, and is layered with memoir, history and myth, particularly African American myths of flight.. The eight year old girl at the center of the book set in Harlem in 1939 is both dreamer and agent of change, imagining that she can wear the George Washington Bridge, which she can see from her roof, like a diamond necklace. She touches lightly on discrimination, mentioning that her father helps build a union building that he can’t join. Family problems are suggested when Mommy cries when the father goes to look for work and doesn’t come home.

All these books remind us that finding beauty can take some effort, dreaming, and trusted helpers. And it’s worth it. E.B. White wrote, “All that I hope to say in books, all that I ever hope to say, is that I love the world.”

January 22, 2016

Children’s Literature: On our Way

I’ve got my books lined up for the semester and held two classes. On the first day we sped through the history of children’s books, taking brief note of medieval and Puritan views of childhood, Nathaniel Hawthorne’s favorite book as a boy (apparently, THE TRIUMPHS OF GOD’S REVENGE AGAINST THE CRYING AND EXECRABLE SINS OF MURDER), Philippe Ariès on the cultural definitions of childhood, Blake and Wordsworth on innocence, and John Newbery, who among his accomplishments as a publisher started a trend for selling toys along with books – a ball for boys and a pincushion for girls, creating a sort of pink aisle, too. For the first time, we got to read this year’s Newbery winner right in class and briefly discuss what we’ll discuss more: the strands of entertainment and teaching. One student saw the Nana in The Last Stop on Market Street as the sort of helper we find in a hero’s journey. We touched on that form, versus the circles we’ll find in Charlotte’s Web and City Dog, Country Frog, which we read the second day, and a student pronounced, “Devastating.”

Also in the second class, we talked about Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, filled with tropes we’ll encounter again — orphans, a magic mirror, enchanted animals, flying, snugness, food, a three-headed dog, wands – and themes of friendship, secrets, death, and good versus evil. How many have read this book before? I asked, and all hands went up. That will never happen again, so I savored. How many have read it ten times? I asked, and it looked like all hands to me, though perhaps one or two arms stayed on desks. Already I love my class.

January 20, 2016

The Boston’s Women’s Memorial

After getting back from a fun trip with my daughter, I took her dog for a walk along Commonwealth Avenue. Henry enjoyed meeting a plump corgi-lab mix named Zeus. He put up with me checking out the Boston Women’s Memorial by artist Meredith Bergmann.

Here is Abigail Adams, wife of the second president, mother of the sixth, with an excerpt from one of her extraordinary letters, which have instructed us about her and the colonial period, written in bronze on the side of the pedestal she leans against.

Phyllis Wheatley was another woman of letters. Her poems published in 1773 were the first book published by an African writer in America: “Imagination! who can sing thy force?”

Journalist Lucy Stone was a nineteenth century abolitionist, suffragist, and founder of The Women’s Journal. We think

they make quite a group.