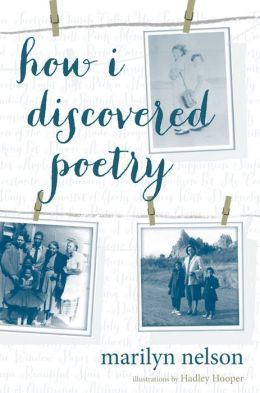

What I’m Reading: how i discovered poetry by Marilyn Nelson

how I discovered poetry by Marilyn Nelson is written in forty unrhymed sonnets, showing a life based on her own, but with added research and imagination, during the 1950’s, when she grew from four years old (as she is in the picture taken by her father below) to fourteen. The first words are “Once upon a time,” and we hear the small child in bed amusing herself not only with the idea of time, but prepositions. The next poem is set in church, where upon hearing that Lot and his wife flee, she imagines companionable fleas within the Biblical story.

As the narrator grows up, the poems told in first person reflect what she learns within the fourteen line frames that, one after another, with line illustrations by Hadley Hooper and a few black and white photographs, seem like blankets pinned at the corners by the four members of the family. The father’s work as one of the first African-American career officers in the Air Force, mean they travel a lot. Her mother teaches second grade and oversees what happens to her two daughters in classrooms where Marilyn sometimes “has the darkest eyes in the room” and sometimes is in an all-black classroom. She shows how both places have their pleasures and difficulties. She sometimes briefly reflects on what she overhears about integration and segregation, thoughts broken by a child’s common wish for a pony. As she grows older, her mother brings home some Africans from grad school and tells her daughter “these are our people.” As the growing poet puts away the supper dishes, she asks herself “who are not my people.”

A developing awareness of the implications of race is a theme, the failures and small triumphs of justice on school playgrounds (we get some seesaw imagery), but the collection is as marked by the travel of a parent in the military, the repeated leave-takings and trying to make new homes, and the glimpses of the variety of people and natural beauty in the nation. As the narrator enters her teens, there’s more sense of her looking for a place for herself beyond her strong family, and while the poet is tentative, as poets tend to be, we are sure she will make mark. In the last lines of the last sonnet, she closes a book, turns off her lamp, and speaks into the dark: Give me a message I can give to the world. The plea or prayer echoes a line from Emily Dickinson, who would become a cherished influence. Then the poem and book concludes with her “afraid there’s a poet behind my face.” Here’s the life: both the yearning and fear of hearing and being heard. I’ll be reading this thought-provoking and beautiful book again.

For the Poetry Friday roundup, please visit No Water River.