Stephen Clapham's Blog, page 5

November 20, 2023

Another of Steve’s articles was linked in the Financial Times

The post Another of Steve’s articles was linked in the Financial Times appeared first on Behind The Balance Sheet.

November 15, 2023

#28 – The Continuous Learner

/*! elementor - v3.17.0 - 08-11-2023 */.elementor-widget-text-editor.elementor-drop-cap-view-stacked .elementor-drop-cap{background-color:#69727d;color:#fff}.elementor-widget-text-editor.elementor-drop-cap-view-framed .elementor-drop-cap{color:#69727d;border:3px solid;background-color:transparent}.elementor-widget-text-editor:not(.elementor-drop-cap-view-default) .elementor-drop-cap{margin-top:8px}.elementor-widget-text-editor:not(.elementor-drop-cap-view-default) .elementor-drop-cap-letter{width:1em;height:1em}.elementor-widget-text-editor .elementor-drop-cap{float:left;text-align:center;line-height:1;font-size:50px}.elementor-widget-text-editor .elementor-drop-cap-letter{display:inline-block}

/*! elementor - v3.17.0 - 08-11-2023 */.elementor-widget-text-editor.elementor-drop-cap-view-stacked .elementor-drop-cap{background-color:#69727d;color:#fff}.elementor-widget-text-editor.elementor-drop-cap-view-framed .elementor-drop-cap{color:#69727d;border:3px solid;background-color:transparent}.elementor-widget-text-editor:not(.elementor-drop-cap-view-default) .elementor-drop-cap{margin-top:8px}.elementor-widget-text-editor:not(.elementor-drop-cap-view-default) .elementor-drop-cap-letter{width:1em;height:1em}.elementor-widget-text-editor .elementor-drop-cap{float:left;text-align:center;line-height:1;font-size:50px}.elementor-widget-text-editor .elementor-drop-cap-letter{display:inline-block} Sebastian Lyon is a conservative investor who manages two highly successful multi asset funds. His motto is simple over complex and he is intent on protecting the downside.

SUMMARYSebastian Lyon is a conservative investor who manages two highly successful multi asset funds. His motto is simple over complex and he is intent on protecting the downside. In this interview, we discuss his views on markets (spoiler: not super bullish), how he built a significant asset management business from scratch, how he has managed his fund to deliver only 3 down years in 20, what he looks for in stocks, why he invests only in quality companies and why he owns gold.

/*! elementor - v3.17.0 - 08-11-2023 */.elementor-widget-image-box .elementor-image-box-content{width:100%}@media (min-width:768px){.elementor-widget-image-box.elementor-position-left .elementor-image-box-wrapper,.elementor-widget-image-box.elementor-position-right .elementor-image-box-wrapper{display:flex}.elementor-widget-image-box.elementor-position-right .elementor-image-box-wrapper{text-align:right;flex-direction:row-reverse}.elementor-widget-image-box.elementor-position-left .elementor-image-box-wrapper{text-align:left;flex-direction:row}.elementor-widget-image-box.elementor-position-top .elementor-image-box-img{margin:auto}.elementor-widget-image-box.elementor-vertical-align-top .elementor-image-box-wrapper{align-items:flex-start}.elementor-widget-image-box.elementor-vertical-align-middle .elementor-image-box-wrapper{align-items:center}.elementor-widget-image-box.elementor-vertical-align-bottom .elementor-image-box-wrapper{align-items:flex-end}}@media (max-width:767px){.elementor-widget-image-box .elementor-image-box-img{margin-left:auto!important;margin-right:auto!important;margin-bottom:15px}}.elementor-widget-image-box .elementor-image-box-img{display:inline-block}.elementor-widget-image-box .elementor-image-box-title a{color:inherit}.elementor-widget-image-box .elementor-image-box-wrapper{text-align:center}.elementor-widget-image-box .elementor-image-box-description{margin:0} GETTING INTO INVESTING

GETTING INTO INVESTINGSebastian’s father was a stockbroker and he bought his first stock at 14 (Steve stupidly forgot to ask which stock!) and set up a Stock Soc at university and did informal internships in different parts of the City of London. He worked in aircraft leasing, corporate finance, stockbroking, market making and in his last university summer in investment management. He preferred that because it was more cerebral and longer term and he went to work as a graduate trainee for the firm where he had interned.

Some takeawaysBuilding an Asset Management BusinessSebastian was asked by Lord Weinstock, the industrial titan who built GEC into one of the UK’s leading companies over 40 years, to manage his family’s money. Sebastian didn’t want to run a family office but started Troy as an investment management firm with a view to attracting external investors. Troy was named after one of Weinstock’s horses which had won the Derby in 1979.

Sebastian’s Investment ApproachWhen he started his career in 1989, the UK market had a very tough time and the residential property market crashed. He saw the UK housebuilders fall by 90%. Domestic cyclicals performed really badly for 3 years. He was therefore attracted then to more defensive businesses.

When he launched the Troy Trojan fund in 2001, just after the dot.com boom, he could see the ridiculous over-valuations in the tech area. And the market had overlooked a lot of high quality values stocks which had been left behind and which he would have preferred to own anyway.

In 2002, the bear market really kicked in but he defended capital well. Weinstock had said to him “I am not interested in benchmarks – don’t lose my money”.

His approach is to avoid torpedoes; to avoid valuation risk; and to emphasise quality which he defines as consistent returns and with lower volatility than that associated with more cyclical businesses. He has never owned a housebuilder, a retail bank or an airline.

He also believes that he needs t be paid to take risk so he flexes his equity exposure down when stocks are highly priced and up when stocks are lowly valued.

What He Looks ForTroy has an investible universe of around 200 quality companies. He likes companies which over the long term have reduced their share count. He pays close attention to the historical record, looking back over the last 10 years – the past can give you a really good indication of how the company has performed. Has it invested well, generated cash or has it been a poor allocator of capital. Has there been a lot of turnover in management?

These are backward looking factors. They then considers the stockmarket aspect and valuation and he tries to be patient and wait for opportunities in these quality stocks, which are rare. They like to buy in when investors are looking the other way.

He has bought Heineken this year which suffered in Covid as the pubs were closed and were hot by increases in energy and input costs after – the stock had gone sideways for five years and people were a bit bored with it. He doesn’t feel there is that much downside and if it does fall further, he will feel confident to add to the position.

He looks for simple businesses which will be straightforward to run and shuns complex businesses. He tries to look at this from the CEO’s perspective. Meanwhile in finance, everyone loves complexity and the more Greek letters the better – Sebastian feels nervous as soon as a Greek letter is mentioned.

He cites the Peter Lynch saying “Know what you own and why you own it”.

Other ShowsIn this episode we referenced past shows with Chris Wood (#8) and with Alec Cutler (#26).

ABOUT Sebastian LyonSebastian began his career in 1989 at Singer & Friedlander Investment Management. He moved to Stanhope Investment Management which managed the GEC Pension Fund in 1995, where he jointly managed the £2 billion equity portfolio and the Fund’s asset allocation. He had the office next door to Lord Weinstock, and they used to discuss stocks which led to Weinstock inviting him to manage his family’s money and to Sebastian establishing Troy Asset Management. He remains Troy’s Chief Investment Officer and is responsible for Troy’s Multi-Asset Strategy. The investment approach is cautious, targeting absolute returns. with a bias towards value investments. Sebastian has a BSc in Politics from Southampton University and enjoys golf and tennis.

Sebastian recommended Money Masters by Jonathan Davis. It runs through 8 investors including Anthony Bolton and Ian Rushbrook, and one of the things that struck Sebastian was that they were all very successful but they all did it very differently. He was particularly drawn to Ian Rushbrook’s methodology incorporating stock-picking and macro/strategy.

Buy on amazon.com Buy on amazon.co.UK HOW STEVE KNOWS THE GUEST

HOW STEVE KNOWS THE GUESTSteve met Sebastian at a breakfast economics presentation by Peter Warburton and has been cajoling him to be a guest for some time now. Sebastian’s clarity of thought and simplicity of approach is refreshing.

Full disclosure: Troy Asset Management is a client of Behind the Balance Sheet and Steve and family are invested in the Troy Trojan fund.

PrevEasy Stock Ideas

The post #28 – The Continuous Learner appeared first on Behind The Balance Sheet.

November 13, 2023

Easy Stock Ideas

Regular readers will know that we ran a 3-day stock idea challenge for our readers some time ago.

Investing should be simple in my view, so there was nothing complicated here. Just three simple techniques from my course How To Pick Winning Stocks. Each day, participants were asked to watch one video lesson and use it to find two potential stock ideas.

To keep everyone on track, we asked them to email them our ideas each day. Here are the methods we suggested:

Day 1 – Think of products you like using, and see if they are public companies

Day 2 – Think of a lateral: something you have seen happen in one geography or sector, which might be repeated elsewhere

Day 3 – See what “super investors” have bought recently

We had a great response and everyone seemed to enjoy the challenge. Not everyone sent us their ideas, but a lot did. I shall discuss some of these ideas below, but first I wanted to show you a set of emails from a lady called Victoria.

I don’t know what Victoria does for a living but she is, or could be, a smart investor. She kindly gave me permission to reproduce her entries below. In return, I’m sending her a copy of my book and free enrolment into our full stock-picking course, How to Pick Winning Stocks.

Victoria’s Stock Ideas & CommentsDay OneTechtronics Industries Company Limited (TTI Group)Helen of TroyWhere these came fromWe’ve recently moved house and had two deliveries yesterday – a new toaster, and a new vacuum and hard floor cleaner.

My approach to buying this kind of product is to look at articles – Which, Good Housekeeping, BBC Good Food Magazine, etc. – where different options have been tested against a common set of criteria and ranked (often in multiple categories – ‘best for …’). Once I’ve narrowed down options, I then tend to have a look to see how the product has been rated by public on John Lewis’ website. I ended up ordering from companies I hadn’t purchased from before – Zwillings and Vax – and ordered direct from companies.

I thought this might be a good place to start – as I had no idea who owned either brand – although I did have vague idea that Vax was British. It turns out I was partially correct about this – Vax was British but is now owned by Techtronics Industries Company Limited (TTI Group), which is listed on Hang Seng. I’d never heard of them but they own several other brands that also came up in my search – Hoover, AEG – as well as brands across a number of other sectors with their website describing them as “a fast-growing world leader in power tools, accessories, hand tools, outdoor power equipment, and floorcare and cleaning”. One of the main commonalities across these different segments seems to be a specialism in cordless technologies. There are potentially two interesting things here – cordless technologies have become possible in part because of the shift to lithium ion batteries from older technologies, and the batteries are interchangeable between products within a range which can help with customer retention/upselling (and I should flag here that I ended up buying both a vacuum and a hard floor cleaner from same range so this seemed to have worked on me at least).

Zwillings is even more interesting – but family-owned so not in scope for this project. However, having reflected on process of how I selected these products and I what I look for, I started thinking about some of the other kitchen/homeware brands I have purchased from over the years. Googling identified that many of these brands are either family-owned or private equity-owned. One brand that I like that was owned by a listed company is OXO Good Grips. This was started by guy when he noticed that his wife’s arthritis was making it difficult to use various kitchen appliances. This is now owned by a NASDAQ listed company called Helen of Troy (which is a genuinely brilliant / terrible company name). They seem to own mix of legacy (Braun, Honeywell, Vicks) and newer brands (Pur (water filters), Osprey (outdoor gear), Drybar and Hottools (both hair products)). I’d never heard of some of the newer ones but Drybar seemed to launch in Harrods last year to some fanfare.

ReflectionsI haven’t looked into financials of either company beyond quick scan of annual reports so not sure if either of these would actually be good investments – but they are both companies I’ve never heard of before and therefore wouldn’t have thought to consider (thus demonstrating Steve’s point). I think this has also helped clarify for me that both of companies I’d purchased from were able to meet my needs because of broader strategic decisions they’d made, which is useful perspective.

More generally, this exercise made me realise how much of my day-to-day life relates to some of largest (and best researched) companies in world – e.g. I bought lunch in Tesco, used Dell and Microsoft products at work, use an iPhone, had to deal with several big utility companies as part of house move (all of whom have hopeless customer service but sadly with no hope of this impacting on their financial performance), etc. Even things I thought might be from smaller companies (for example, what I think of as more niche skincare and soft drinks brands) turned out to be brands owned by large multinationals (L’Oreal and Nestle).

Day TwoIdea 1: I watched video just before heading out to lunch, which I bought at Pret. This led to me reflect on the emergence of food chains (Pret, Leon, Itsu, etc.).

When I started work the main lunch options seemed to be bringing your own sandwiches, getting something from local cafes/deli, or Boots Meal Deals. This made me wonder whether other countries have seen similar shift – and in particular if there are any markets that are at earlier stage in this process and where there might be a business with lots of potential for growth.

Pret, Leon etc. are quite highly concentrated in London. I suspect this is largely because of economic geography of UK. Other European countries tend to be less economically concentrated than UK so there could be good scope for a brand to grow across multiple cities.

Idea 2: We visited Iceland a few years ago and one of really impressive things is way they used geothermal heat in all sorts of clever ways, including to heat greenhouses, allowing them to grow fruit and vegetables in Arctic. This clearly has benefits in terms of food security, reduced costs, and environmental impacts.

On a similar note I read recently about project in Norway where excess heat from data centres was going to be used to heat water for an onshore trout farming. And I think Stockholm already uses excess heat from multiple data centres to heat homes. I suspect there will be more of push to think about how we make better use of all available energy options include reuse of heat – so I wondered if there are any companies (perhaps in industrials/engineering/software) that are well placed to take advantage of this opportunity.

Day ThreeI looked at number of portfolios including Baupost Group (Seth Klarman) Gotham Asset Management (Joel Greenblatt), GMT Capital (Tom Claugus), and Crake Asset Management (Matthew Taylor).

My main reflections are the variety in number of holdings, that all seem to have a few holdings that are substantially larger than the rest, and the presence of some of largest and best known companies (Apple, Amazon, Intel, Walt Disney, Marriott, etc.) in these portfolios.

Two companies (out of many that would be interesting to look at) are iTeosTherapeutics Inc and KLA Corp. Both are from Gotham Asset Management’s portfolio.

iTeos Therapeutics was their largest new purchase in Q1 2022, becoming their 23rd largest holding. I’ve included it as it’s absolutely not the kind of company I expected to be this portfolio – so I’d like to understand why it is.

Lots of the portfolios I looked at had exposure to semiconductors companies. KLA Corp “designs, manufactures and markets process control and yield management systems for semiconductor and related nanoelectronics industries”. Given passing of CHIPS Act, and drawing on the oil services companies example in Day 2, I thought this might be interesting company to explore in more detail.

Many thanks for course. I’ve found it very useful and enjoyable!

Victoria

Steve’s TakeI was impressed with Victoria’s Day One picks – this was a great exposition of how to find an interesting stock idea from personal experience. Her suggestions as to laterals and areas to explore from Day Two were also illuminating – although she didn’t pick beneficiaries, she had a couple of themes which she could pursue over time, especially the geothermal/energy efficiency angle.

I find this sort of exercise helpful and used to employ this strategy at the hedge funds. I now know that geothermal is in my sphere of interest and once I have registered that, I will no doubt see dozens of opportunities in this area. It’s like when you buy a new car and are surprised at how often you see the same model.

Copying ideas from great investors is a strategy I couldn’t deploy at the hedge funds. Because of the size of our positions, we had to be in before anyone else. Also, your boss isn’t going to offer much reward for copying a competitor, even if it’s a good idea. For private investors, though, it’s a smart strategy – and Victoria executed it well. This is because she asked what the information meant, rather than just taking it at face value. This is a vital skill for digesting investment information in all forms, and a key part of my lessons on reading company accounts.

More Ideas From The ChallengeParticipants shared a couple of hundred potential stock ideas (I haven’t finished counting). The stress there should be on potential, as they are just quick ideas – not fully researched ones.

I have split the list into two, as otherwise there are simply too many to take in. Below is a round-up of some themes we saw from each day. The full list of potential ideas is in a spreadsheet for my lovely paying subscribers and those who took the challenge (first part this week, more to follow). I love you all of course, but some a little more.

Day One – Personal ObservationMicrosoft was the standout here. Now of course this is just a matter of finding ideas, nothing about valuation – should we do a valuation challenge? Let me know.

Alphabet came up here as did CROCS, interestingly, as it had been a staggeringly strong share last time I looked (10+ bagger form pandemic lows to 2021 high). I was also surprised to see people suggesting shorts here, and there is one stock that I am definitely going to look at (highlighted in the sheet).

Day Two – LateralsThere were a lot of suggestions on the theme of the tragic war in Ukraine being extended. Some related directly to defence, some to equipment suppliers. Other popular themes were inflation pressuring incomes and a general economic slowdown. These both those surfaced discount chains and value retailers like Dollar Tree and Dollar General. Trading down in cars flagged Autozone and O’Reilly (which it was pointed out had already run).

Day Three – Great InvestorsPicks from everyone from Sir Chris Hohn to Prem Watsa, including some names that you might not have heard of like Victoria’s pick of Martin Taylor’s Crake Capital. I am going to look at one stock which Peter Lynch holds in size (highlighted in the spreadsheet).

Paying subscribers can read on to find the full spreadsheet link and a genius idea-hunting method suggested by one participant. The sheet will also be sent to people who took the challenge first time round.

This is a subject we shall come back to as we haven’t covered even half of the ideas.

The post Easy Stock Ideas appeared first on Behind The Balance Sheet.

November 6, 2023

The Original Tiger King

I never met Julian Robertson but he is one of my investing heroes. Not just because of his amazing, albeit chequered, investment record, but as a former partner of a Tiger cub, I also owe him a great debt.

I first came across Tiger Management when I was working on the sell-side. I had joined a new firm to cover a new sector, conglomerates, and my old patch of transport. A few days in, a salesman flew in from New York and asked if I had any shorts. I was a little confused as to why my new colleague was interested in my casual wear, until he explained that he covered hedge funds, which invested in long and short ideas. Until then, my only exposure had been a meeting with Soros on a long idea, and I had never heard of a hedge fund – imagine!

I explained that the most expensive stock in my universe was Eurotunnel, which would go bust without an injection of equity. He immediately called James Lyall at Tiger on speakerphone. A 15 minute call was enough to get James interested, and we ended up selling 3% of the company short for Tiger. They made 90% on the trade, and in those days you also got interest on the cash. Although I don’t remember exactly how big their bet was, it was over $100m for sure.

Eurotunnel Boring Machine, Source: alamy.com

Eurotunnel Boring Machine, Source: alamy.comI have not researched Robertson before, but I have always felt grateful to him. Both for giving my old employer a job, and for retiring in 2000 at the top of the tech boom. If he hadn’t, my boss might never have set up on his own and I would have missed that wonderful opportunity.

There have been a lot of obituaries, but I wanted to capture a few of Robertson’s practices and look at how we might try to emulate his success. To be clear, he was an amazing stock-picker and that cannot be replicated. But he had some useful principles which we can perhaps apply today.

There have been a lot of obituaries but I wanted to capture a few of Robertson’s practices and look at how we might try to emulate his success. To be clear, he was an amazing stock-picker and that cannot be replicated, but he had some useful principles which we can perhaps apply today.

BackgroundRobertson was born in 1932, in Salisbury, North Carolina and graduated from the University of North Carolina in 1955. He served in the Navy for two years before starting on Wall Street as a stockbroker for Kidder, Peabody & Co.

In 1974, he became CEO of the firm’s investment advisory subsidiary. In 1978, Robertson left and took a one year sabbatical in New Zealand where he wrote a novel which was never published. He decided to invest instead and with a partner in 1980 started Tiger Management as a long-short equity hedge fund with $8.8m of joint capital. He would later move into global equities, and eventually into commodities, currencies, and bonds.

Robertson was an investing genius. From inception in May 1980 to its peak in August 1998, Tiger earned an average of 31.7% pa after fees, vs a 12.7% pa return on the S&P 500 index. Even after losses from the tech boom shorts and bad macro bets in 1999-2000, the average performance was 26% pa. Over 20 years!

But an interesting fact about Robertson which goes unremarked is that although he was a brilliant investor and made himself a billionaire, the Tiger funds likely lost money for investors overall – as always happens, the assets grew at the peak of the funds’ success and the losses then likely exceeded the gains in the good years; these were phenomenal but on lower AUM.

How Robertson Built His TeamThe Tiger Cubs (founded by his former proteges) and Grand Cubs (founded by proteges of the Cubs) are the most successful group of hedge funds ever. Robertson’s selection of analysts is therefore particularly interesting. He believed that successful investors have certain characteristics beyond intelligence and numeracy and looked in particular for people who were competitive:

“..almost as important as total honesty and smarts is competitiveness. The guy who just will not be beaten in performance, simply will not be beaten in performance. When we hire anybody, we give them a long test and there are several things on this test that help us discover their competitiveness. The beauty of this test is that we have tested so many managers. When you consider John Griffin, Stephen Mandel, Lee Ainslie and Andreas Halvorsen, these managers are almost legends”.

The Templeton Touch, William Proctor and Scott Phillips

I don’t know to what degree competitiveness as in seeking to win races or games is an essential characteristic for investing success. But it’s clearly helpful, not least because it keeps you going in the face of adversity.

“We eventually devised testing that all applicants had to take. We still give that test, which takes about three or four hours. It is part aptitude, but also psychological. The test was also designed to show what kind of team player the person was and their competitiveness. I’ve found that most good managers are great competitors”.

Source: Value Investor Insight

Robertson was a jock – competitive and athletic. He flew the team to Montana and Wyoming and set them gruelling physical challenges, often with a view to team bonding. They would hike, climb, swim in ice cold lakes, and camp out. The analogy is the US Navy Seals – one of the team, Andreas Halvorsen (who founded Viking, still one of the top 10 global hedge funds, before Tiger blew up), was a member of that elite group. Robertson was a great believer in teamwork and went on to employ a psychologist who devised the test for potential recruits.

And the analysts loved it as the rewards were enormous, with 8 figure bonuses on offer, sums unheard of in the 1990s. Robertson ensured peak performance by having a gym in the office and when an analyst had a baby, a nanny was sent to ensure that their sleep was not interrupted.

Robertson was also age agnostic, and if anything favoured younger analysts.

“We never made a mistake there [in giving a manager too much too soon] and in fact, that is what our strength is, giving these young managers the responsibility we did at the time. “

The Templeton Touch, William Proctor and Scott Phillips

I think we can learn from Tiger and from successful sports teams, as investors often under-appreciate the value of teamwork. I am not sure you need a group of jocks and I suspect Tiger’s team was less diversified than is thought optimal today. But it worked for them.

The Investment ProcessTiger analysts had free rein to make recommendations and roam the world in search of great stock ideas, but Robertson was the sole trigger-puller.

“He would assemble his lieutenants each Friday around a long table to listen to the fruits of their week’s work, and the emotional payoffs were extreme. “That is the be-yest idea Ah ever saw,” he might exclaim after listening to a square-shouldered twenty something analyst deliver a stock pitch, and the young hunk would be whooping and high-fiving himself inside his swollen head for the rest of the meeting. “That is the dumbest idea Ah ever heard,” Robertson might also say, in which case six-foot-plus of Wall Street alpha male would shrivel pitifully.”

More Money than God, Sebastian Mallaby

Robertson was a brilliant stock-picker.

“He could drop in on a meeting with a chief executive and demonstrate a grasp of company detail that rivaled that of the analyst who tracked it. He could listen to a presentation on a firm he knew nothing about and immediately pounce on the detail that would make or break it”.

More Money than God, Sebastian Mallaby

Here’s what Jim Chanos had to say about Julian Robertson and his process:

“When it came to interacting on stocks, there was no one better than Julian Robertson. He would have you over for lunch and if you were pitching a short idea, and he would have you against eight bulls, and vice versa, and just challenge you on every part of your thesis, which is the way really professional investors should do it”.

Robertson believed in deep research, at a time when there was no internet, research was much more difficult, but could construe a real information advantage.

One of Tiger’s analysts thought that a South Korean car company had a model with a faulty engine, but the information was secondhand and Robertson insisted on primary research. Tiger bought two of the cars and had them tested. The results validated the short. Sure enough, the vehicles were clunkers. Tiger successfully shorted the stock. Another analyst validated an Avon thesis by becoming an Avon representative.

Robertson was similar to Buffett in that he looked for easy wins. To borrow Buffett’s metaphor, he was looking for one-foot hurdles he could step over:

“Hedge funds are the antithesis of baseball… you can….hit lots of home runs, but you will not make money playing in the minor leagues…you have to play in the big leagues. In the hedge fund business, you simply get paid on your batting average. So you go the places where the pitching is not any good and you hit there. We were one of the first into Korea and those markets were absurd. People would buy stocks based on the absolute price without considering what could be earned back…I firmly believe that it is smart to go places where there are rookies in investing.”

The Templeton Touch, William Proctor and Scott Phillips

Like Buffett, his approach changed over time.

“When I first started the hedge fund, I generally bought very cheap stocks with low valuations. And then, when we hired all of these wonderful analysts, I realized that we could do much better in our investments by getting more into growth companies, because our guys were pretty capable of mapping out what the growth was going to be, and so we shifted into that approach.”

The Templeton Touch, William Proctor and Scott Phillips

Tiger’s Closing LetterRobertson’s closing letter (March 30, 2000) noted the redemptions, some $7.7bn since August 1998, and talked of “the demise of value investing”. There are some obvious parallels to the recent market regime in 2021/22.

”There is no quick end in sight”? What is ”end” the end of? ”End” is the end of the bear market in value stocks. It is the recognition that equities with cash-on-cash returns of 15 to 25% regardless of their short-term market performance are great investments. ”End” in this case means a beginning by investors overall to put aside momentum and potential short-term gains in highly speculative stocks to take the more assured, yet still historically high returns available in out-of-favor equities.

…the key to Tiger’s success over the years has been a steady commitment to buying the best stocks and shorting the worst. In a rational environment, this strategy functions well. But in an irrational market, where earnings and price considerations take a back seat to mouse clicks and momentum, such logic, as we have learned, does not count for much.

The current technology, Internet and telecom craze, fueled by the performance desires of investors, money managers and even financial buyers, is unwittingly creating a Ponzi pyramid destined for collapse. The tragedy is, however, that the only way to generate short-term performance in the current environment is to buy these stocks. That makes the process self-perpetuating until the pyramid eventually collapses under its own excess.

I have great faith though that, ”this, too, will pass”…. The difficulty is predicting when this change will occur and in this regard I have no advantage. What I do know is that there is no point in subjecting our investors to risk in a market which I frankly do not understand. Consequently, after thorough consideration, I have decided to return all capital to our investors”.

TributesA Bloomberg article carried these tributes:

David Saunders, K2 Advisors:

“He was most harsh when we were performing the best. He’d say, ‘We should be making more money.’ He was quiet and almost kind when things were going against us.”

John Griffin, Blue Ridge Capital:

“His passion was contagious and his integrity unquestioned.”

Philippe Laffont, Coatue Management:

“Julian was a legendary investor and a generous mentor. But above all, he was a person of extraordinary integrity — someone who personified not just what it meant to lead a successful professional life, but who embodied the deepest love of family, a humorous disposition in friendship and a profound commitment to philanthropy. He did so much good in the world, and so often when nobody was looking.”

Chase Coleman, Tiger Global Management:

“Julian was a pioneer and a giant in our industry, respected as much for his abilities as an investor as for the integrity, honesty, loyalty and competitiveness he demonstrated as a leader. He made the time to be a true mentor, always leading by example and pushing all of us to become the best versions of ourselves.”

Lee Ainslie, Maverick Capital:

“Julian was a mentor and a friend to so many people who aspire to live up to his example as both a great investor and an extraordinary philanthropist.”

Stan Druckenmiller, Duquesne Family Office:

“…while his intuitive genius produced amazing returns, and the philanthropic achievements he used those returns to fund were equally impressive, I will always remember him for the class and dignity that was pervasive throughout.”

Steve Mandel, Lone Pine Capital:

“Julian was an amazing mentor, a first-class human being and I will miss him terribly.”

Chris Shumway, Shumway Capital:

“Julian was a brilliant investor, incredible mentor, amazing contributor to society and a great friend. I know I speak for many when I say I could not have found a better mentor and friend who was an engineer of positive change for all who came into contact with him.”

The post The Original Tiger King appeared first on Behind The Balance Sheet.

October 30, 2023

Investing On The Edge Of Doom

The death of Queen Elizabeth really is the end of an era. She was an amazing leader and set a fantastic example. I don’t have a high regard for the UK’s upper class and inherited wealth does not merit respect. But the Queen was a majestic figure. My UK readers will have to endure the press for the next 10 days and although she is a great loss – I think many of us feel as if we have lost a distant relative – I think we should be celebrating her life and her achievements. She was 96, after all. The Tweet at the end contains a great clip which underlines her sense of humour, bordering on mischievous. I just wanted to say something here, because she was one of the constants in a declining nation and I have had an enduring admiration for her.

MarketsYou, dear reader, may not be aware that I took August off, because I wrote 7 columns in July and scheduled them in advance.

I spent most of the month in the US and did very little work other than responding to emails and the odd urgent client Zoom. I restarted this week, or rather last Saturday, when I appeared on a panel on the Money stage at the FT Weekend Festival in London.

Claer Barrett, the FT columnist and podcaster, was the moderator and opened by suggesting that the panel would try to stay cheerful – I failed to oblige. I thought it might therefore be worth repeating some of my comments and the advice I gave to the attendees here.

The FT Money Panel Photo Courtesy someone on Twitter whom I forgot to bookmark, sorry

Photo Courtesy someone on Twitter whom I forgot to bookmark, sorryIncidentally, the FT Weekend Festival is a fantastic event and I have attended almost all of them as a paying guest (this was my first time as a speaker). Even better, you can now catch up on what you missed in person, online.

I pointed out to the audience that I am a glass half empty sort of person when it comes to investing, and that downside protection is my priority. I then explained that I was not investing in the 1970s, but that it is the only period I can recall, other than the 1929 Depression, where the circumstances were similar to today. The economic outlook has never been this bad in my experience and we start at a point where markets are likely overvalued. As a result, you should be resigned to seeing your real wealth decline in the next ten years and you should have a plan to mitigate the adverse impacts.

This is not just my view. One of my friends, who manages a billionaire’s family office and has immense resources at his disposal, recently passed a similar message to his employer. I shall suggest some potential mitigating actions later for my paying subscribers, but let’s first look at why the prognosis is so gloomy.

Most of what I shall discuss is focused on the US and UK, the two most important markets for me and my readers. But the symptoms are fairly consistent globally.

ValuationsWe start from high levels of valuations relative to history in most markets – equities certainly and in almost every region, but especially the US; bonds generally; and property. The three main asset classes are richly valued by historical standards. I say this first because valuation is always important.

Our recent equity correction from the peak is modest. The S&P500 started the year at just shy of 4800 and is now at c.3900, a fall of c.19%. Not great, but hardly a disaster. Five years ago, it was 2461, so it’s up nearly 60% (before dividends) – well above long term historical averages.

The FTSE100 in the UK has fared better this year, down 4%, partly because of sterling’s weakness, and partly because of the weight of energy and commodity stocks. It’s down 2% over the last 5 years! Again, before dividends.

Importantly, equity valuations are generally rich (although the UK is not as dear as some other markets). And these valuations are based on margins and returns which are also near peaks. They may not revert to historical means, but the odds are certainly against further significant gains.

Bond yields have risen but remain low by long term standards. And property is still close to the peak.

That we are likely in a bear market is borne out by comparison with past bear markets, an exercise Jeremy Grantham of GMO carried out in a recent article called “Entering The Superbubble’s Final Act”.

“From the November low in 1929 to the April 1930 high, the market rallied 46% – a 55% recovery of the loss from the peak.

In 1973, the summer rally after the initial decline recovered 59% of the S&P 500’s total loss from the high.

In 2000, the NASDAQ (which had been the main event of the tech bubble) recovered 60% of its initial losses in just 2 months.

In 2022, at the intraday peak on August 16th, the S&P had made back 58% of its losses since its June low. Thus we could say the current event, so far, is looking eerily similar to these other historic superbubbles.”

Market action since Powell talked tough at Jackson Hole supports this bear market premise. Such markets are characterised by higher volatility and sharp rallies. These make investing tricky, and you therefore need a long term plan.

Economics – Short TermPart of this summer’s relief rally came from the hope that inflation had peaked, largely thanks to a 0% month on month CPI print in July. But as Greed and Fear pointed out, 18 of the 36 CPI components actually accelerated. And if inflation remained at 0% until the end of the year, we would still exit 2022 at 5.4% pa inflation, hardly a major win and much higher than the 2% Fed target.

This remains critical – Jan Hatzius, Chief Economist at Goldman Sachs and a cut above the average of the breed, said in a recent Odd Lots podcast that he believes the Fed will be aggressive on rate rises until the inflation rate begins with a “3”. (I think this is an excellent podcast and Joe Weisenthal and Tracy Alloway dig into many otherwise unexplored areas.)

Clearly, the combination of quantitative tightening (or QT) and higher rates is a reversal of the policies which fuelled the market’s rise. When you add in high inflation, and particularly rising energy prices, you have an unattractive cocktail. And that ignores pressure on food supplies, partly related to Ukraine situation but also to unprecedented drought conditions globally.

Europe will also suffer the food cost pressures and greater pain from rising energy costs and the availability of gas. Martin Wolf in the FT (Europe can — and must — win the energy war) discussed the IMF’s assessment of the impact on Germany of cutting off Europe’s gas (they predict 1.5/2.7/0.4% of GDP in 2022/23/24).

If Russia shuts off Europe’s gas, it will be a disaster for Germany. I calculate the IMF’s impact at c.$110-120bn in 2023. That seems much too low – BASF’s revenue is just shy of $100bn, obviously not all sourced from Germany but that is a good context. If Russian gas stops, Ludwigshafen (BASF’s massive chemicals complex) surely will have to close, but it’s the knock-on effects which really matter – car factories will close because they will be short of components, as will large swathes of German industry. This sounds much larger than a $100bn problem – $200bn, $300bn, could it be more? A friend at a large hedge fund agreed the IMF forecasts look highly conservative.

In the UK, I spent time with the management of John Lewis this week. It’s a well-run business with a sensible team that aren’t afraid to talk. This was prior to new PM Truss making any policy announcements and the team were all concerned about the next two years. I expect that the news of fuel price caps will have been a great relief, although there will clearly be a price to pay at some point. It made me think that survival is the most important goal in any consumer facing enterprise – conservative financing and a quality management team will count for a lot, going forward.

An area which has gone relatively uncovered, which is a surprise to me, is China. Obviously the zero-Covid policy is a disaster (although it is helping depress Chinese oil demand which is down 6-7m b/d and capping oil price rises). But the Chinese real estate sector is one of the largest asset classes in the world and it’s in dire straits. This is important as it’s a major component of Chinese household wealth; the middle class often invest in second and third properties.

Since the scale of Evergrande’s problems surfaced, confidence in the sector has been receding. Sales are now running down 30% (by floor space) and starts are down 35%. Home prices are in decline and unless this is reversed, volumes may not pick up. Recent initiatives to relax interest rates and deposit requirements may not be enough to persuade speculative investors. They clearly form a large part of incremental demand, although I have never seen any good estimates of the degree.

The problem for China is that residential real estate is an engine of economic growth. It’s not just the 20-25% of GDP it represents. Local municipalities often rely on land sales for 30-40% of their revenues and this is already drying up with sales at 2000 levels, according to Greed and Fear. In a recent FT article, Megan Greene said that 30 real estate companies there have now defaulted. She puts real estate at 60% of local government revenues and 70% of household wealth.

This looks to be a real crisis and Chinese growth may not even hit the 3.5% consensus level for 2022. Major US companies like Tesla and Apple rely heavily on sales in China. I would be worried about Apple which is on a consensus P/E of 25.5x for the year to 9/22, falling to 24.1x next year. With the strength of the dollar, the impact of inflation, the lack of an exciting new phone (US prices are the same as the previous model, although dollar strength may offset inflationary pressures) and general economic weakness, I wouldn’t be in a hurry to add – forecasts are surely at risk.

To be fair, not everyone views the short term as negatively as I do. There is hope that Government support, like the new UK Prime Minister’s initiative to cap energy bills, will limit the damage. Here is a take from one wag on Fintwit.

We went through a Pandemic & 2 years of lockdowns, yet Fintwit expects the world to end this winter, whereas the problem is solved if you drop your heating by 2 degrees & wear a sweater indoors instead of a T-Shirt.

— Le Shrub est Tres Court

And we will bail out utilities like we did with banks in '08pic.twitter.com/2OorzNjCxY

(@agnostoxxx) September 7, 2022

Somehow, I doubt it will be that easy, but to be fair, Governments can cushion the impact, as they did in the pandemic, at the expense of further increasing already bloated debt burdens.

Economics – Longer TermGrantham’s piece flags a number of longer-term issues which I also think are important.

Labour force availability – demographics are now working against us. More pensioners and fewer workers, when we already have full employment and are struggling to fill vacancies.

Climate – drought conditions aren’t just affecting farming. Waterways for transport are being impacted, notably the Rhine. My recent visits to the Boulder and Glen Canyon Dams highlighted low water levels and the risk of electricity supply to LA. Grantham writes:

“ French nuclear power stations have had to reduce production because rivers are too hot to be used for cooling; China has had to halve its hydropower (18% of its electricity), which has also been reduced in Canada, Norway, India, and elsewhere by low water levels”

And high temperatures are affecting agriculture.

Moreover, the issue of food availability which Grantham cites as a short-term issue could also become a longer-term problem with population growth, higher energy costs inflating the cost of fertiliser and climate impacts.

Meanwhile, productivity growth has been very slow; we have the longer-term issue of de-globalisation which is inflationary (and likely to be accelerated by the weakness of the RMB). Financial repression is possible or even likely, with Russell Napier arguing that governments will force savers to buy their bonds. This would mean a reduction in equity exposure.#

The SolutionEven in the 1970s, it was possible to make a real return by buying the right equities. Paying subscribers can read on for my tuppence worth (ok, $16/month worth). But first, here is the clip about the Queen.

this remains an all-time story about the queen pic.twitter.com/hI2yNUac0H

— David Mack (@davidmackau) September 8, 2022

The post Investing On The Edge Of Doom appeared first on Behind The Balance Sheet.

Adventures In ESG Land

I intend to cover ESG – Environmental, Social and Governance – in more detail both on my podcast and Substack. It has received critical attention in a couple of my podcasts:

In Episode 8, Chris Wood suggested that ESG had peaked.

In Episode 9, Jeremy Hosking said that ESG had created a capital cycle opportunity in the energy sector which had been denied capital, laying the foundations for a spike in oil prices.

On the same day that Albert Saporta was decrying ESG and claiming that it should stand for Energy, Soya beans and Gold, I spotted a couple of unusual ESG-type funds whose focus was on the “S”, which tends to get less attention.

For me, Governance has always been an integral part of my process, while E is an obvious risk factor – I think of “E” as Emissions and the risk is climate/carbon costs. Therefore, I was curious about these new funds whose marketing focuses on the “S.”

The Harbor Corporate Culture Leaders ETF has the ticker HAPY and invests in Human Capital:

“The Human Capital Factor strives to deeply understand company culture and intrinsic employee motivation as a potential driver of stock performance.”

The Carmignac Portfolio Human Xperience fund is described in its marketing literature as:

“A thematic fund invested in companies that demonstrate strong customer and employee satisfaction. Companies that provide positive experiences to their customers and employees may be better positioned to achieve superior returns over the long term.”

Harbor claims that its approach is backed by data. “’The Human Capital Factor‘ is grounded in a robust, nonreplicable dataset of both public and proprietary sources, covering 2,200+ public firms, 10m+ employee responses totaling 500m+ data points.”

“The Index is designed to deliver exposure to ’corporate culture leaders‘ based on scores produced by Irrational Capital LLC, companies with high ’Human Capital Factor‘ scores, which are determined by Irrational Capital in accordance with a rules-based methodology that seeks to identify companies that best manage their human capital, resulting in highly motivated and engaged employees.”

Human Capital Factor Source: Irrational Capital

Source: Irrational CapitalIrrational Capital was founded by the highly respected behavioural economist Dan Ariely. How his firm derives a human capital score, I have no idea. A JP Morgan research report was highly favourable. But the idea is not daft, as for most companies their greatest asset is their workforce. And the ETF charges 0.50% fees, so it’s not a ridiculous investment proposition. Harbor has launched a second ETF, based on the same strategy, the Harbor Corporate Culture ETF (HCFI) using a 150-stock index.

Harbor may not be so happy with HAPY though. It hasn’t performed that badly, -12.27% since inception on February 23 2022, but its AUM (assets under management) are only $6.9m.

HAPY Stock Price Source: Stockanalysis.com

Source: Stockanalysis.comThe Carmignac Portfolio Human Xperience Fund explains its philosophy in the graphic below but provides limited detail on how it derives data on employee and customer satisfaction.

Human Experience Factors Source: Carmignac

Source: CarmignacThere is quite a lot of data about the fund on the website, as is usual for a UCITS vehicle. Assets are allocated c.60% US, c.30% Europe and c.10% Asia. The four Asian holdings are Samsung, Hyundai Motor, Lenovo and JD.com – none springs to mind as paragons of virtue in employee treatment and I wonder about the customer satisfaction. It’s hard to judge when we don’t know how Carmignac decides these factors, of course.

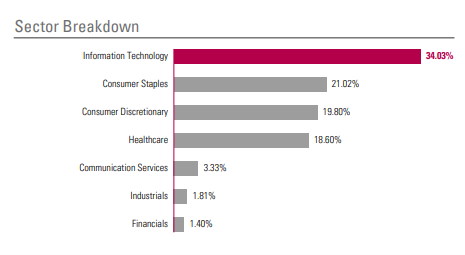

Assets by Sector Source: Carmignac

Source: CarmignacThe fund is heavily weighted towards tech, as can be seen from the chart, and looks to have a zero weighting in energy. I would have thought companies like Shell were models of virtue in dealing with employees and would have quite a high score in customer satisfaction also. I didn’t see much mention of ESG in the literature, but I expect the manager prioritises other ESG characteristics.

ESG Scoring Source: Carmignac

Source: CarmignacInterestingly, the largest position is in food company General Mills. A full list of portfolio constituents and a review of changes in the past year is in the spreadsheet for paying subscribers. The weighting of the largest 10 positions is 37.5% and there were 39 stocks in total at end of the last quarter and 40 the year before, so the fund is reasonably concentrated, which I like.

Top Ten Stocks Source: Carmignac

Source: CarmignacAnd the performance has not been bad, given the weighting to tech. The manager bailed out of Netflix, which had been a 3% position. There has been a reasonable amount of churn with 17 stocks sold and 12 stocks added, according to my quick review. Here is the performance chart.

Performance Since Inception Source: Carmignac

Source: CarmignacHere is the manager’s commentary on performance:

“The Fund posted a negative performance due to volatile equity markets and fears about growth, as consumer confidence indices hit a 40-year low worldwide. The consumer staples industry benefited from the high levels of inflation, whereas our exposure to consumer discretionary – the first to fall victim to inflation – proved costly. Nvidia, a processor and graphics card supplier, Amazon, Hilton and Marriott were among the stocks that weighed particularly heavily on performance. Lululemon and Adidas were also sources of disappointment, but our stock-picking within the consumer staples and healthcare segments, including Procter & Gamble, General Mills, Novo Nordisk and Sanofi Aventis, raised performance. Due to declining social scores, we reduced our exposure to Accenture, which failed to live up to expectations. Conversely, we strengthened our positions in Sodexo, the global catering and prepaid services giant, after it announced better-than-expected revenue and a return to pre-pandemic margins in 2023.”

Wait, Sodexo, the contract caterer . . . is it noted for its excellent treatment of employees? Its inclusions surprised me as did that of Compass. I have done a fair amount of work on Compass and met management and IR several times, and never did they mention employees in a private meeting. Between them, the two contract caterers employ about 1m people – I find it surprising that they would be included in a fund which has a focus on employee satisfaction.

Other stocks included which surprised me were Delivery Hero, Walt Disney, Hilton and Marriott. Again, I should point out that I have not studied employee relations at any of these companies and my surprise is simply from the perspective of a customer and observer.

Perhaps I need to do some more work, but the manager explains how stocks are picked as follows:

“The ratings and selection process are an integral part of fundamental company analysis and is conducted according to our proprietary model based 50% on customer experience and 50% on employee experience.”

And here are the customer and employee experience factors, which they presumably conduct surveys to assess, as I cannot think how else it would be achieved.

Customer experience: client satisfaction, customer welfare, data privacy, quality and product safetyEmployee experience: employee satisfaction, corporate purpose, diversity and inclusivityDelivery Hero riders might be happier than Uber drivers, I have no idea, quite honestly, but would they score highly in employee satisfaction? Maybe their scores are not high in absolute terms but their rivals fare worse, which could give them a competitive advantage?

Walt Disney might have smiling employees, but my understanding is that employee satisfaction is pretty low, especially at the theme parks where most of them work.

And Hilton and Marriott might have happy and loyal customers (I am in both rewards schemes, for example) but when was the last time you saw a hotel chambermaid tap-dancing to work?

I am a little sceptical about their inclusion.

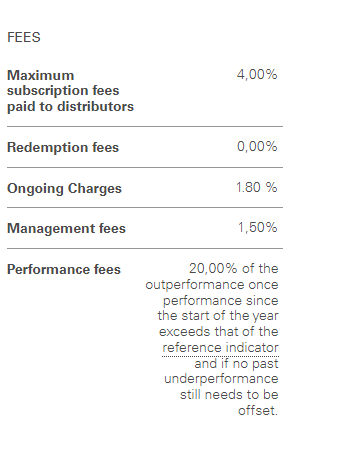

But the real surprise on the Carmignac fund, which looks like a perfectly sensible portfolio with a composition that is easy to see as being ESG-friendly, is on the fees. The schedule is below.

Carmignac Human Xperience Fund Fees Source: Carmignac

Source: CarmignacYes, it’s not quite 2 and 20 but pretty close. I think the benchmark is the ACWI and, to be fair to the manager, the performance has been reasonable given the sector bets and I am not complaining about the stock selection. But I wonder how happy Carmignac is with this fund since it has assets of just €19m.

The post Adventures In ESG Land appeared first on Behind The Balance Sheet.

October 24, 2023

Learning From The Top 1%

In mid-2021 I started work on my podcast. For me this was another new medium, and one slightly trickier to master than my video attempts on YouTube. I had started my YouTube channel in January of that year. I didn’t worry too much about my production quality with the videos – as long as you could see and hear me, I felt that was good enough (and in line with my tech capabilities). But for a podcast, the production quality had to be higher, which created something of a learning curve and required expert assistance.

Incidentally, I am not sure about this picture which is overly flattering. First, the photographer made me look better than I am in the flesh, then the cartoonist takes at least 10 years off the guests which of course they love. I have had a bit of flak about this.

To test the market, I kicked off with an initial series of five episodes. I was surprised at how much I enjoyed doing them and at the warmth of the response, so I continued. The reason I enjoy the process, and I think the reason for its popularity, is that I am learning a lot (as is the audience, I hope). I have been engaged in the investing game for decades, but this was the first time I had sat down with real experts and discussed how they approached the stock market. And my wonderful guests really opened my eyes.

Every investor approaches the market in a different way, but there are of course many commonalities. It’s incredibly helpful to listen to great investors. In my Analyst Academy Course, I have about 30 bonus lectures in which I expose students to the investing philosophy of Buffett, Graham, Klarman and many more. You cannot be a successful investor until you have developed a philosophy which suits you – everyone has their own interests, aptitudes and risk tolerances. Generally, this is a process developed over several years of making mistakes and losing money – you need to learn what makes you lose sleep, and what risks you find manageable, but also how best to approach the stockmarket puzzle. Learning from the greats is a good way of developing your own philosophy. And my podcasts can help.

Hokusai’s Feminine Wave Source: Wikipedia

Source: WikipediaA common theme from my guests is an inherent dissatisfaction with performance. Wikipedia comments that the great Japanese painter, Hokusai, on his deathbed said:

“If only Heaven will give me just another 10 years . . . Just another five more years, then I could become a real painter.”

This from a man whose paintings were an inspiration for Monet (a memorable work is on display at the French Impressionist’s former home at Giverny). Yet he was constantly seeking to improve.

What struck me from a number of my podcast conversations was how dissatisfied many of my guests were with their own performance. This isn’t a question of wanting to earn more money – they mainly have more money than they could spend in a lifetime – but an issue of wanting to improve, to be hungry, and to get better.

The advice from John Armitage, founder and CIO of $28bn hedge fund Egerton Capital (EP 1), to young aspiring investors was to work hard; it was echoed by Quintin Price, former head of BlackRock’s active strategies (EP 4). Armitage, whose 27-year track record is staggering, said: “I like working. I never feel successful. I measure success by the recent past.”

He attributes his success to a decent dose of insecurity and being a workaholic. His ingredients for success are:

Finding something you likeFeeling you have more to learnAnd always worryingThis is not to say that you need to be insecure to be a great investor, but it’s no coincidence that so many great investors also display humility which is in contrast to their financial success. I recently sat down offline with one of the most successful hedge fund managers in Europe and he had the same mantra – how can we improve?

For many of my initial guests, it was their first time on a podcast and for some their first ever interview. But they nevertheless had fantastic answers. A good example is Stuart Roden (EP 2). He explained his impression of the five characteristics of a good investor – he had clearly spent time analysing his own performance. He also explained that there is an important difference between analysts and portfolio managers – analysts want binary answers, while the skill of a great portfolio manager is taking on uncertainty and risk.

Roden, who has retired from Lansdowne and is mainly involved in philanthropic activities, contrasted life in fund management and afterwards – there are few other endeavours where you can make things happen so quickly and then turn on a dime to pivot.

Quintin Price explained that great investors have extraordinary clarity of thought; are not proud about reversing their decisions; and understand what process works for them.

Pete Davies, who runs the Lansdowne Partners Developed Market Strategy, recommended (EP 3) that young (and older) investors should look back at a period in history which they haven’t experienced or explored.

Lucy Macdonald (EP 5) was the global CIO Equities at fund behemoth Allianz and had some simple advice for a young analyst or portfolio manager. It may however be difficult to execute:

“Get a good boss.”

She explained that your first boss can have a profound impact on your career, so you need to make sure they are someone who can properly teach you.

When running an investment team, Lucy placed emphasis on avoiding groupthink. She used blind voting (where you cannot see how others are voting). It means a wider dispersion of opinion and often creates additional debate which is helpful in arriving at the right decision. Her three tips for avoiding groupthink:

Leader goes last and does not influence othersDiversity of inputs (gender and background) is importantBlind votes (ie others cannot see how you vote)More recently, I have interviewed a few macro commentators while I try to make sense of what happens next as we exit a 40-year regime of falling rates. Jeremy Hosking and Russell Napier (EP 9) commented on the fact that many investors have come into the business in the past 10 years and it would be easy to assume that:

An era of falling rates and massive liquidity was normal;Growth stocks would be pushed to excessive valuations, especially in private markets;Companies in the real world would continue to be starved of investment; and thatMean reversion was a 20th-century phenomenon.As we are now learning, such assumptions need to be questioned.

I have learned so much more and this is just a quick snapshot of a few highlights. I hope you will learn a lot too!

The post Learning From The Top 1% appeared first on Behind The Balance Sheet.

October 19, 2023

Steve was a speaker at the CPA Australia Flex Forward Congress

The post Steve was a speaker at the CPA Australia Flex Forward Congress appeared first on Behind The Balance Sheet.

October 16, 2023

Taking One For The Team

Introduction

When the Financial Fair Play rules were first introduced, my friend Tim Keogh persuaded me that we should build an app to analyse football clubs’ performance on and off the field. The app was genius we thought. Indeed, we attracted a bid from a French hedge fund manager and football club owner whom I knew; but we preferred independence and then failed to make a fortune.

A Still from the Footy Finance App Source: Behind the Balance Sheet

Source: Behind the Balance SheetIn spite of fun stats like the goal value ratio (the number of goals you saw at home games divided by the cost of a season ticket), or goal efficiency as shown in the still above (how much each club spent to generate a goal), the apps were not as popular as we hoped. And as it involved a huge amount of data compilation (23 teams each year, full accounts data, football data, almost all manually entered), I got bored and we abandoned the project.

But it was tremendous fun working with Tim who is a data visualisation genius (a really useful skill today and one which is under-rated and under-taught: watch out for our new course launching in Q4). We almost sold the concept to Tesco to educate their retail staff about individual shop performance. I am still hopeful that we shall do a similar project, because how many companies can effectively communicate their financial performance to employees on the shop floor?

Football (or soccer, if you prefer) is a goldmine for data analysts as there is a huge amount of information available, even in real time. I met someone recently who is part of a professional betting syndicate. They pay a fortune for real-time feeds of dangerous free kicks and penalties which enable their automated systems to hedge their bets. It has become a sophisticated investment activity.

Investing in Soccer ClubsFootball (soccer) has generally been an unattractive investment. I was reminded of this when recording two recent podcasts. Episode 9, which aired in April, included Jeremy Hosking, who at one point had a major investment in Crystal Palace. I believe he is one of few people who actually made money investing in a football club, since it was subsequently promoted to the Premier League, where the broadcasting rights are incredibly lucrative. Relegation is a financial disaster for clubs.

And in Episode 10, I interviewed Lord (Jim) O’Neill, the man who coined the term Brics, former chairman of Goldman Sachs Asset Management and a lifelong Manchester United supporter. He has been an outspoken critic of the Glazers’ stewardship of the club and it led me to look at the share price chart.

Manchester United Share Price ($) Source: Behind the Balance Sheet from Sentieo data

Source: Behind the Balance Sheet from Sentieo dataI was quite surprised when I looked to see that since IPO the stock had flatlined while the S&P500 had trebled. Subsequently, the price has dropped even more. This is partly a reflection of the strength of the dollar as the club earns in sterling. This long-term trend surprised me, given the increased market recognition of the value of global media content. It made me wonder how other clubs had fared.

There are not many quoted football clubs and some are small and rarely traded. The list includes AFC Ajax, Benfica, Borussia Dortmund, Celtic, Juventus, Lazio, Olympique Lyonnais, Porto, and AS Roma, as well as Manchester United. Rangers and Arsenal have quotes but rarely trade. Rangers actually went bust ten years ago.

It’s odd that a major sport and media industry gets such limited coverage in the financial press, but that has been changing with

The purchase of Newcastle United, led by the Saudi sovereign wealth fundScandal at Manchester City, with accusations of illegal payments by the Abu Dhabi ownersThe three or four-way skirmish for Chelsea after sanctions forced Abramovich to sellThe more recent fight for AC Milan, currently owned by hedge fund ElliottI expect more of this trophy asset hunting, but what of the share price performance – can investors profit? The received wisdom always used to be no – in effect, the increased broadcasting rights simply end up in players (and sometimes agents’) pockets. We had thought the financial fair play rules might alter the balance, but that premise proved inaccurate. Here is our index of football clubs’ performance:

Behind the Balance Sheet Football Club Index Performance Source: Behind the Balance Sheet from Sentieo data

Source: Behind the Balance Sheet from Sentieo dataOur index, which is not market cap weighted so that Man Utd doesn’t weigh down the basket, is extremely rough-cut and directional only, shows an appreciation of just under 25% over the last 10 years. When you consider that

The value of global media assets has multiplied many times over that periodThe value of stockmarkets has doubled over that periodWell, 25% doesn’t seem that great.

I don’t have good quality data on the financial performance of all these quoted clubs but the average EV:Sales looks to be around 3x and there is only limited profitability in aggregate. My original theory that the bulk of the increases in the broadcast revenues finds its way to the players’ pockets looks likely to be a sensible explanation.

Other StudiesA McKinsey study finds that team market value is correlated to on field performance which is not surprising but I suspect is based on unreliable estimates of player values, is short term in nature (the diagram looks at one season) and rather theoretical.

McKinsey Correlation Analysis Source:McKinsey

Source:McKinseyWhen we studied the Premier League financial performance, I recall that only Manchester United managed to make a profit from buying and selling players – and that was mainly because of the sales of Beckham and Ronaldo. I would be surprised if any Premier League club managed that well today, although Joseph, our in-house football expert, reckons some European clubs have done well at this aspect of the game, notably Ajax and Benfica.

Joseph argues that Ajax and Benfica have excellent youth scouting and training systems plus the benefits of scale in their home countries. This means they either get the best talented 10-year olds or just buy the best youngsters from smaller teams in the country after one good season. I am not sure that this is a profit stream which would attract a high multiple but it certainly improves the quality of the investment.

In our study of the English Premier League, we found that the 37 clubs studied spent £5.5bn on players and made a loss on the players they sold of £1.1bn. The numbers today would of course be much larger.

I was amused to see that a recent paper on the use of crypto currencies by football clubs suggests that crypto tokens don’t offer any benefit over football equities. The authors suggest that first-day trading pops are huge but that the tokens underperform crypto benchmarks, and that the valuations of tokens were unaffected by performance on the pitch.

Other SportsAlthough oligarchs and sovereigns like these trophy assets, and although they should be geared to the increased values of the related media assets, investing in football teams doesn’t seem to work, unless you take part in a turnaround (like Jeremy Hosking with Crystal Palace). A better way to get involved is through a central body, like the system at Formula 1. There the teams don’t make any money, but it helps Ferrari to sell cars and presumably Mercedes hope for some reflected glory. Again, it tends to be a plaything for billionaires such as Lawrence Stroll or for enthusiasts like the late Sir Frank Williams who managed to run a team on a relative shoestring compared with the big boys today.

Williams GP Share Price Source: Behind the Balance Sheet from Sentieo data

Source: Behind the Balance Sheet from Sentieo dataWilliams entered liquidation in 2020, so that was obviously not a great investment, and the chart shows that holders had limited opportunity for gain in its near-10 year life. But sport, especially global media plays, has intrinsic appeal and I plan to take a closer look at Formula 1 as an investment. Ideas for other plays would be welcome.

Manchester UnitedJust to square the circle on Man U, I downloaded a few key tables from their 20-F (the equivalent of a 10-K for international filers) looking back 10-odd years to review some of the key metrics. One of the issues many retail investors have when looking at a new company is they try to apply the same standardised metrics.

This approach has certain advantages – you can cross refer the metrics across companies, you are familiar with them and you will find them easy to calculate. But I like to use the analogy of a toolbox – a mechanic will have a wide selection of tools in his toolbox, so that when he has to attack that unusual bolt or screw, he has the right tool. He generally won’t use a pair of pliers to loosen a bolt. Investing is similar – you need to have a wide selection of tools and techniques to apply to different companies and industry sectors.

The distinguishing characteristic of a sports team is that the players are capitalised on the balance sheet and amortised. If you want to understand MANU stock, this is where you need to focus. The first chart shows the employee cost to sales; revenues have recently been distorted by Covid, notably the lack of home match revenue; but even in fiscal 2019, employee costs rose to more than 50% of turnover, with a corresponding adverse impact on the margin.

Manchester United Employee Cost Trend £000s Source: Behind the Balance Sheet from Sentieo data

Source: Behind the Balance Sheet from Sentieo dataThe second chart looks at the cash spent on players and the proceeds from player sales. It’s clear that the annual spend has been increasing, but the proceeds from sales are well short – there is a shortfall of more than £100m a year, or 20% of revenues. Of course, one of the largest costs is amortisation, so we should look at the 30%+ EBITDA margins rather than the now single figure EBIT margins, and it’s possible that this is sustainable. But the cash released from player sales relative to revenue is lower than the average in the league when we analysed this data, and it leaves limited cash for other uses, like rewarding shareholders.

Manchester United Player Purchases and Sales £000s Source: Behind the Balance Sheet from Sentieo data

Source: Behind the Balance Sheet from Sentieo data

The post Taking One For The Team appeared first on Behind The Balance Sheet.

October 9, 2023

Doomed to crash?

Introduction

Aston Martin is launching another rights issue, to raise £635m, bringing in Saudi Arabia’s sovereign wealth fund as a 1/6 shareholder via a placing; and the Saudis, Mercedes and Lawrence Stroll are investing a further £335m in the rights issue. The announcement was greeted with relief in the stockmarket. But this is just the latest in a long string of financial rescues for the long-time ailing car company which has gone bust almost as many times as its famous customer James Bond has come back from the verge of death.

Aston floated in London in October 2018 at £19/share through a secondary issue in which the vendors raised £1.051bn. No new money was raised for the company. Within 18 months, the Aston Martin returned to the market for £500m of new money, raised in a dilutive rights issue and a placing at £4. The company has also tapped the debt markets.

The day after the initial IPO announcement, I appeared on the Today Programme on BBC Radio 4 to discuss the float. (For overseas readers, this is the most popular news show on UK radio with about 7 million daily listeners). The night before, I had had a quick scan of the private company’s accounts which suggested all was not quite right – massive capitalisation of R&D and limited liquidity were my main issues. When asked about the opportunities for the company, I responded that the proposed SUV should do well – “there are a lot of fat old men who can’t get into an Aston Martin who will buy it” – and let’s see how it is priced.

Source: Aston MartinIPO and subsequent share price performance

Source: Aston MartinIPO and subsequent share price performanceA few months on and I was telling friends and clients to be very careful – the accounting looked terribly aggressive and in spite of the obvious liquidity strains, the IPO was not raising any new money, which seemed mad to me. The chart shows how the share price has fared since the IPO.

Aston Martin Share Performance Since Flotation Source: Behind the Balance Sheet from Sentieo Data

Source: Behind the Balance Sheet from Sentieo DataThe shares have been a disaster and there were some very obvious signals. In this article and a subsequent one, I want to look at the treatment of intangible assets. In a later article, I shall look at the liquidity picture, as well as some of the other issues.

The Initial PictureThe Aston Martin prospectus showed that the company was capitalising almost all its R&D spend as shown in the table:

Aston Martin R&D Note Source: Aston Martin IPO Prospectus

Source: Aston Martin IPO ProspectusThe prospectus explained the high level of R&D: “..continued investment in new core models as part of the Second Century Plan, in particular new Vantage, DBS Superleggera, DBX and increased investment in special projects which include the Aston Martin Valkyrie. During the six months ended 30 June 2018, the methodology applied to the capitalisation of development costs for new cars was refined to more appropriately reflect the point at which the development phase starts in the current development process. The impact of this change on the six months ended 30 June 2018 was that approximately £9 million more development costs were capitalised.”

My impression was that the bulk of the R&D must have been for the new DBX SUV and that there would be a build-up of R&D on the balance sheet. I didn’t realise how fast it would be accumulating. By the end of 2017, capitalised development hit £830m gross and £511m net. By the end of 2018, it reached £653m net after £214m spend and £202m capitalisation. In 2019, the company spent £226m and capitalised 100% and the asset rose to £770m.

Aston Capitalised R&D Movements Source: Behind the Balance Sheet from Aston Martin Reported Data

Source: Behind the Balance Sheet from Aston Martin Reported DataWhen the DBX came into production in 2020, amortisation started to hit the P&L and the asset hit £1.437bn gross and £784m net, still an increase on end-2019, as the £178m of spend was only partly offset by a charge of £93m and impairment of £69m. In 2021, spending continued at a rapid rate, with another £178m added to the asset and only £129m of amortisation, giving an end-2021 picture of a £1.6bn asset, accumulated amortisation of £781m and a net asset of £833m.

But it’s not just the capitalised R&D. Aston’s balance sheet now carries £1.4bn of intangibles. Let’s take a closer look.

Start with the Audit ReportWhen I open a new set of accounts, I have a fixed sequence that I always go through. One of the first checks is the audit report. Apart from the usual checks: