Ross Lawhead's Blog, page 9

January 19, 2014

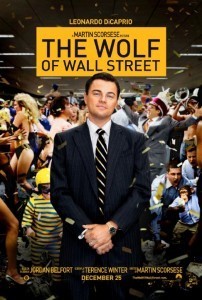

“The Wolf of Wall Street”: Mirror or Window? Acting or Act?

The Wolf of Wall Street (2013)

The Wolf of Wall Street (20013) is a very powerful and accomplished film. As a film school dropout, I can speak to Martin Scorsese’s abilities as a filmmaker and say that there was hardly a scene in it that was not directed with almost perfect craft and there was a good deal of invention (or judicious “borrowing”) in how the story was told. From a technical point of view, it was clear that a master in full control of his craft was at work, directing with a lively imagination and exuberant joy. And while it’s okay to admire the movie, it’s wrong to actually enjoy it, and these are the reasons why…

The story itself was a kind of Catch Me If You Can (2002) meets Wall Street (1987), set in the 90s. Its message is very clear. It is not about the love of money. Money is not what it is about. Money is talked about, and shown, a great deal, but what it is really about is greed. It is about what happens when completely unalloyed greed takes over a person’s heart, mind, and soul. We are repeatedly reminded by several characters that the money in itself is not important, it is the making of money that drives the characters in the movie, and therefore is what drives the plot. And all of the events in the story are told from Jordan Belfort’s point of view, related directly to the camera by Leonardo DiCaprio with unapologetic glee.

In fact, it’s glee that best describes the entire movie — from the very spirited performances that litter the film throughout to the very movements of the camera itself, all of it is suffused with glee, and its this glee that presents a moral issue in watching, let alone enjoying, this movie. Far beyond the constant nudity and drug use in this movie, the most arresting scene for me is an early one in which a woman who works in Belfort’s office is given $10,000 in cash, for the entertainment of her cheering (or is it jeering? We are never allowed to be certain) workmates. The tenor of the style is ironic — we are meant to appalled at the unabashed immorality of the excesses that we are witnessing a recreation of. However, the compelling thing about the hair cutting scene is this: her hair really is cut off. As far as I can tell, her hair is actually cut off. And the question I had at that point is: did the actress get paid $10,000 for that scene?

Somehow I doubt it. And it’s possible that there’s a very clever make-up artist somewhere that is feeling smug about themselves, but I think it’s far more likely that an actress was found to do it for considerably less than that. And if so, how is a woman shaving her head for money for the amusement of her office any more reprehensible than an actress shaving her head for the amusement of a worldwide audience? And so what is happening now to us watching this movie? Are we being presented with a window to view someone else’s depravity, or a mirror in order to view our own? And how impressed are we to be with a host of highly paid actors portraying self-entitled drugged-up hedonists? Are we watching acting or the act itself? The line between imitation and reality becomes very unsettlingly blurred.

Martin Scorsese with Leonardo DiCaprio and Margot Robbie

So what, then, is the purpose of the movie? It makes its point very adeptly in the first half hour, with the most insightful and concise points of the movie given to us by a very on-form Matthew McConaughey. The following two and a half hours is merely elaboration of what is done and said in that one scene, hammered home with increasing profanity and debauchery. The pretense to educate is fairly thin. At two points the character of Jordan Belfort begins to tell the audience exactly how he was able to do what he did but then he stops himself, tells us that’s not what we’re interested in, and then invites us to witness more of the movies purported true-to-life grotesqueries. A much more informative, and therefore more profound, movie about such Wall Street shenanigans would be Enron: The Smartest Men In The Room (2005) or Inside Job (2010).

“Sell me this pen,” is a recurring demand in the movie. It is Belfort’s test of a person’s ability to generate money purely for the sake of acquisition. It’s the act of selling and it’s what moves money from your pocket into their’s. Throughout the movie “the buyer” is constantly debased and ridiculed and by paying to watch this movie we have given money to this pointless cavalcade, not of Wall Street’s self-absorbed over-indulgence, but of Hollywood’s. The patsies are us as we put our money into Scorsese and his studio’s pocket.

July 21, 2013

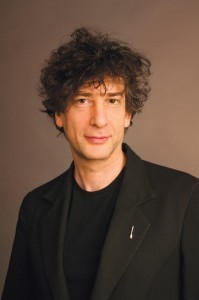

Gaiman’s Ocean and Chesterton’s Giant

“The Ocean At The End Of The Lane is a novel of childhood and memory. It is a story of magic, about the power of stories and how we face the darkness inside each of us. It’s about fear, and love, and death, and families. But, fundamentally, I hope, at its heart, it’s a novel about survival.”

This statement by Neil Gaiman appears on the back cover of his latest book The Ocean At The End Of The Lane. And like most statements by authors about their own works, it is wildly inaccurate, nearly to the point of being completely untrue. The statement is made in absolute earnestness and without a shred of guile, but what Mr Gaiman says his book is about applies less to this book specifically, but entirely to the reason he writes books at all — which are the best reasons that any writer writes for, and arguably the only reason any author ever should write.

This statement by Neil Gaiman appears on the back cover of his latest book The Ocean At The End Of The Lane. And like most statements by authors about their own works, it is wildly inaccurate, nearly to the point of being completely untrue. The statement is made in absolute earnestness and without a shred of guile, but what Mr Gaiman says his book is about applies less to this book specifically, but entirely to the reason he writes books at all — which are the best reasons that any writer writes for, and arguably the only reason any author ever should write.

The list of things that Gaiman claims that The Ocean At The End Of The Lane is about are not what it is about, it is only what the book contains. The book has magic, love, and families in it, but it is not about magic, love, or families. He says it is about the power of stories, but it is not. Mr Gaiman has written other stories about the power of stories, but this is not one of them. It is one of the most powerful stories he has ever written, however, and this is because of the few things the book actually is about, his book really is about survival. It is about surviving life, which is what every great book — that is, every book that is useful to humanity — is about, and Mr Gaiman is right to apply this statement to his book because what he has written really is a Great Book.

The best justification for fairy tales ever written can be find in two short essays written by G. K. Chesterton, collected in his book Tremendous Trifles (1909). They are short essays because the need for fairy tales can be very plainly stated in perfectly plain logic. (J R R Tolkien’s longer essay On Fairy-Stories covers nearly the exact same ground, it is only more exhaustive in its reasoning and referencing.) The core of Chesterton’s argument for Fairy Tales is this:

The best justification for fairy tales ever written can be find in two short essays written by G. K. Chesterton, collected in his book Tremendous Trifles (1909). They are short essays because the need for fairy tales can be very plainly stated in perfectly plain logic. (J R R Tolkien’s longer essay On Fairy-Stories covers nearly the exact same ground, it is only more exhaustive in its reasoning and referencing.) The core of Chesterton’s argument for Fairy Tales is this:

“Fairy tales do not give the child his first idea of the monster. What fairy tales give the child is his first clear idea of the possible defeat of the monster. The baby has known the dragon intimately ever since he had an imagination. What the fairy tale provides for him is a St. George to kill the dragon. Exactly what the fairy tale does is this: it accustoms him for a series of clear pictures to the idea that these limitless terrors had a limit, that these shapeless enemies have enemies in the knights of God, that there is something in the universe more mystical than darkness, and stronger than strong fear. When I was a child I have stared at the darkness until the whole black bulk of it turned into one black giant taller than heaven. If there was one star in the sky it only made him a Cyclops. But fairy tales restored my mental health, for next day I read an authentic account of how a black giant with one eye, of quite equal dimensions, had been baffled by a little boy like myself (of similar inexperience and even lower social status) by means of a sword, some bad riddles, and a brave heart. “

And this perfectly states the intent behind Neil Gaiman’s The Ocean At The End Of The Lane, as well as his other Fairy Tale books, Coraline and The Graveyard Book. In all of these books he has created worlds filled to the brim with evil and danger — fantastic worlds which we instantly recognise as being more real than our own world because the evils are more easily identified, and the dangers more abrupt — and placed at the centre of them one single, vulnerable child. This may or may not prove to be the most meaningful story of mankind — but it is the first story of mankind. It is the story of each of us being suddenly born into a world of more evil and corruption than we can define, our first great anxiety. And to be told this, and to be shown the way to survive it, is the highest purpose of literary art — which Aristotle terms catharsis, which is the cleansing of emotions, which is another way of absolving the soul of the fears that it experiences.

Common elements can be found in Gaiman’s works, as well as all the great authors of Children’s Book (the first educators) such as Roald Dahl and The Brothers Grimm, which are useless, if not actively hostile, parents; an evil from the wilderness or an outer-realm; and help from the ancients. This is not to say that this book (or any of these stories) are formulaic — that is one thing that Gaiman will never be accused of — but that this book follows the logic of truth, for parents are the first authorities that are proved to be fallible (since they are also human), that the first evil we experience is that from outside of humanity, and that the first hope of salvation can be found in the wisdom of those who have gone before us. Gaiman’s Fairy Tales follow this logic because he loves the truth of its outworking, he loves his characters too much to ever go easy on them, and he loves us, the audience, too much to ever lie to us and say that there is no life without danger, and no victory without personal sacrifice.

Common elements can be found in Gaiman’s works, as well as all the great authors of Children’s Book (the first educators) such as Roald Dahl and The Brothers Grimm, which are useless, if not actively hostile, parents; an evil from the wilderness or an outer-realm; and help from the ancients. This is not to say that this book (or any of these stories) are formulaic — that is one thing that Gaiman will never be accused of — but that this book follows the logic of truth, for parents are the first authorities that are proved to be fallible (since they are also human), that the first evil we experience is that from outside of humanity, and that the first hope of salvation can be found in the wisdom of those who have gone before us. Gaiman’s Fairy Tales follow this logic because he loves the truth of its outworking, he loves his characters too much to ever go easy on them, and he loves us, the audience, too much to ever lie to us and say that there is no life without danger, and no victory without personal sacrifice.

All of this love shines through every paragraph of The Ocean At The End Of The Lane and that is what makes it a complete delight to read. The ultimate solution to the evil encountered in the story (which I won’t spoil for you) is as close as Gaiman has yet come to the Christian Gospels. The question of what exactly was sacrificed and what exactly was restored is pretty much the same paradox that was argued for four hundred years after Christ’s death. Yet the story is Gaiman’s own and no one else’s. He is a master of the craft of storytelling and his works put the lie to such heretics as Joseph Campbell, Christopher Vogler, Syd Field, and their progeny which champion the one-size-fits-all storyline. The form of Gaiman’s stories are his own. The purpose and length of each section, chapter, and sentence are appropriate to the story he is telling — finely judged and measured like a perfectly tailored suit, not the tent-sized baggy absurdity which characterises the Hollywood blockbuster.

The Ocean At The End Of The Lane is a brilliant modern fairy tale because it affirms all that is eternal about us, our nature, evil, the world around us, and teaches us the truth which is obvious to us as children and which we forget as adults, and how all of that becomes resolved. We need to keep being told fairy tales because we need to keep being reminded that fairy tales are always true — more true than mere fact because were this story merely factual, it would apply to one person at one time. But because it is fiction it applies to all of us, all throughout history, before and beyond.

The Ocean At The End Of The Lane is a brilliant modern fairy tale because it affirms all that is eternal about us, our nature, evil, the world around us, and teaches us the truth which is obvious to us as children and which we forget as adults, and how all of that becomes resolved. We need to keep being told fairy tales because we need to keep being reminded that fairy tales are always true — more true than mere fact because were this story merely factual, it would apply to one person at one time. But because it is fiction it applies to all of us, all throughout history, before and beyond.

Buy The Ocean At The End Of The Lane at Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, Barnes And Noble, and Blackwell’s. All of G K Chesterton’s works are in the public domain and you may download Tremendous Trifles for free from Project Gutenburg (please donate). The essay quoted is called “The Red Angel”, which is a continuation of the essay “The Dragon’s Grandmother” which immediately precedes it.

July 14, 2013

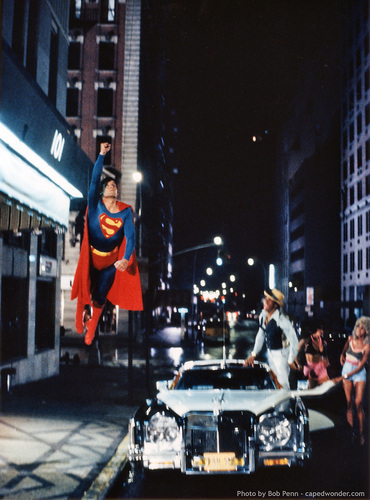

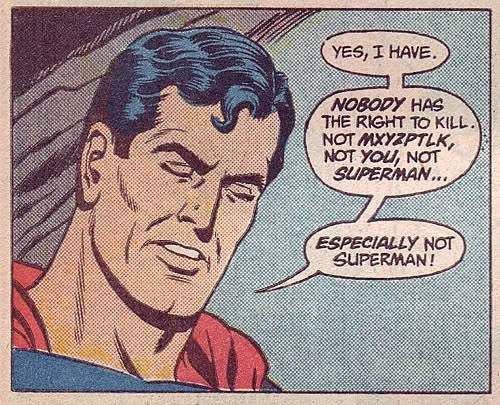

Superman’s First Words

**Contains Spoilers — however, can a bad movie really be spoiled?**

SUPERMAN’S FIRST WORDS

It is night, and a helicopter is spinning out of control just above a thirty story building. It lurches to a halt at the rooftop’s edge and a woman dangles from it, screaming for help as crowds of people clamour below her.

A meek-looking man in a suit and hat picks up a yellow dress hat that has just fallen behind him. He studies it and looks up to where it fell from. Suddenly alert, he rushes away, dashing across the street and into a revolving door which spins faster – faster – and fast until the man emerges again, but now dressed in a bright blue costume and red cape. A fashionably dressed man sitting on a car with scantily-clad women witnesses this transformation. “Say, Jim! Whoa! That’s a bad outfit!”

The costumed man turns to the man and holds up a finger. “Excuse me,” he says, takes a light spring, and shoots up into the sky.

Superman: The Movie (1978)

This is how my generation first experienced Superman, in the 1978 Richard Donner movie. I never saw it in the cinema, but I do remember watching it for the first time on TV, perched on a hotel bedroom, at the age of five. It remains to this day the best cinematic portrayal of any superhero, and the reason for it are those first two words that Superman delivered, and which are so descriptive of what made the Christopher Reeve/Richard Donner Superman so perfect.

The Superman of the 70s was endlessly polite. Even to people who were outrightly rude to him he treated with patience and respect. He moved at superspeed, but it was rare that he rushed anywhere. The actor Christopher Reeve instilled the character of Superman with absolute confidence. And not only was he was completely aware of his own strength and power, of his surroundings and environment, but he was also completely aware of every other person around him, and not just their physical safety, but their emotional well-being also, as every line of dialogue in Superman’s first full scene portrays:

“Easy, miss,” he says upon catching a plummeting Lois. “I’ve got you.”

“You’ve got me? Who’s got you?”

Superman smirks at this and gives a little chuckle. Of course no one needs to ‘get’ him, but he deigns to laugh at Lois’s rather facile wordplay in order, you get the feeling, to save her embarrassment in a strenuous (for her) circumstance. He continues up the building and meets the helicopter as it makes its journey downwards. He grips it with one hand and flies it back up the building, giving a comforting glance to Lois as a father might give to a two-year-old.

Superman: The Movie (1978)

Landing the helicopter back on the rooftop he calls out “Gentlemen, this man needs help!” And gestures to the unconscious pilot. Then he turns to the agog Lois and tries to diffuse the tension of the situation. “Well, I certainly hope this little incident hasn’t put you off flying, miss.” Lois cannot help shaking her head. So long as it’s with him, she’d fly anytime and anywhere. “Statistically speaking, of course, it’s still the safest way to travel.” And then, with one of the largest and most winsome smiles in movie history, he turns away, just about to leap away into the night when…

“Wait!” Lois has called him so he stops and turns. “Who ARE you?”

Superman is more serious now and he says steadily, and without a hint of the irony he has shown through the last three and a half minutes he replies: “A friend.” He leaps into the air calling out an informal “‘Bye!” as he disappears into the night.

This is the pure, distilled essence of what Superman had come to represent in the forty years up to that point. He wasn’t different to us, he was us — a perfect version of humanity, not only physically, but morally. He always knew, unquestionably, what the right thing to do was, in any situation. The only uncertain factor was whether he, even with all his incredible abilities, he had the power to do the right thing. This is an important point, and this is what the generation that created Superman, the generation that survived and won World War II, imparted to us with the creation of Superman: the right course of action is never uncertain, it is only extremely hard to achieve — sometimes impossibly hard — but it is never in doubt. That is something that the creators of Superman understood, and it is something that people in the late 70s still remembered.

THE SUPERMAN WE DESERVE

But how much has changed in the thirty-five years since? And what sins have we committed to now be punished with Zack Snyder and Christopher Nolan’s vision of Superman in his Man of Steel? In the 1978 movie Superman rescues a cat from a tree. Faced with the same situation, the Superman of 2013 would have to agonize internally about the girl’s plight for a few moments while he experienced a vivid flashback where a random parent figure expressed disappointment in him before eventually slinking off into the shadows, self-disgust visibly weighing on his shoulders, leaving the little girl to weep after her still-imperiled pet.

All of the important elements of Superman’s character, his personality, have been excised. His confidence is gone, his self-awareness has vanished, and his moral certainty is a raw, gaping maw of absence which he suffers the lack of through the entire movie.

For some reason, the right thing to do is not clear to Superman/Clark Kent. It takes Kal-El thirty-three years to become Superman. And even then it seems that rescuing people isn’t a moral imperative to him, but merely a concept worth exploring. He is completely untethered by any moral sense, and no character in the movie is able to help him. The floundering Clark Kent even goes into a church at one point and asks a minister of the church what to do. The priest, in complete contradiction to two thousand years of unwaveringly insistent Christian theology, says to him “What does your gut tell you?”

God help us.

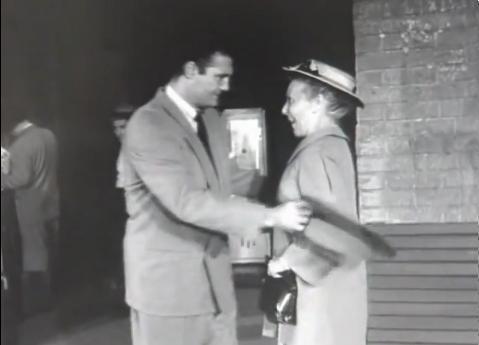

“DOOM’D FOR A CERTAIN TERM TO WALK THE NIGHT”

An elderly woman stands at a bus station, saying an emotional goodbye to her son who is moving to the big city after the death of his father.

“You’ve got a responsibility to the world, Clark,” she says to the young man who towers above her. “You’ve got to accept it. Make use of your great powers.”

Superman Comes To Earth (1952)

This scene is actually from the first episode of The Adventures of Superman TV show from 1952. And a more accurate antithesis of the themes surrounding Man of Steel could not be stated so precisely. The modern Clark has altruistic instincts, but they are brow-beaten out of him at a very young age. He is unable to accept who he is because he is emotionally blackmailed into not using his powers at all.

All of this is due to his adoptive father, Jonathan Kent who, early in the story, berates a young Clark for saving a school bus full of children. Nearly the exact same scene appears in Superman: The Movie and ends with children cheering the departing superhero. In Man of Steel, the young Clark gets berated by his father. The reasoning is thus: if people discover what you can do, Clark, then they will turn against you, and try to destroy you. The message is clear: think of yourself before others, you are more important than they are, their lives are not as important as your privacy.

It is rare to come across a soul as warped as Pa Kent’s is in Man of Steel. “People are afraid of what they don’t understand,” Pa tells young Clark at one time. If that sounds familiar, it’s because that’s nearly word-for-word what one of the villains of another Christopher Nolan movie says. Carmine Falcone to Bruce Wayne in Batman Begins says “You always fear what you don’t understand”. Bruce’s father says to Bruce “Why do we fall? So we can learn to pick ourselves up.” Whereas Pa commends his son for staying down in the dirt when he is bullied, echoing a scene in the movie where Clark walks away from a situation where a drunken trucker sexually assaults a waitress. Witness the teachings of Pa Kent.

In a final scene of overwhelming senselessness, he actually runs into a tornado to rescue his own dog and then orders his son not to save him; martyring himself to selfishness.

Man Of Steel (2013)

Shakespeare’s Hamlet also had a ghostly father who appeared to badger and bully his emotionally sensitive son. The modern Superman has two ghosts of his father which appear interchangeably throughout. Whereas Hamlet’s father criticizes his son for what he isn’t, both of Clark’s dead fathers praise him for what he isn’t allowed to be right now, but will be, one day. No wonder Clark is confused. Both fathers, apparently gifted with the ability to see the future, tell Clark — repeatedly — that one day he will be able to be who he truly is… but not yet. What has to happen first before humanity is worthy to be saved is never explicitly stated, but it becomes clear that what had to happen was for aliens to invade earth and demand that their the member of their own race who has been hiding on earth be returned to them.

No biggie, it would seem. Better for Clark to indulge his tortured soul on board an alien spacecraft than on the planet earth if the Kryptonians are really going to cause such a fuss. And all wold be well and good except that they want to transform earth into a New Krypton, tweaking it’s environment so as to make it hostile to humans — apparently missing the upside of the fact that if they kept it as it was then they could all live there as super-powered beings. Or perhaps send their terraforming device to Venus and set up shop there.

But if this movie tells us anything about Kryptonians, it’s that their intolerant impatience is exceeded only by their relentless violence. Even their top scientific minds — Superman’s father Jor-El, for instance — are able and willing without hesitation to disarm a squadron of guards with their bare hands, leap onto flying dragons in the middle of a fiercely raging mid-air coup d’etat and don suits of armor to battle rebellious generals. Lives are cheap on Krypton, and the desire for rampant destruction is evidently genetic as we arrive at what is the most profoundly disturbing aspect of Man of Steel, and that is how much destruction Superman himself participates in.

Man Of Steel (2013)

REWARDS

I’ve been a reader of Superman comics for a little over twenty years now and in my own collection I could find, at a conservative estimate, probably about a hundred panels of Superman standing over rampaging villain thinking “I have to get them to where they can’t do any damage!” This consideration does not even seem to flit across the Man of Steel’s face as the totality of Smallville is reduced to rubble in a three-way battle between Superman, Zod’s militia, and the U.S. Army and Airforce. The battle then very quickly moves to Metropolis (Manhattan) where Superman viciously beats down a pointlessly wrathful Zod, throwing each other into buildings, scrabbling for chunks of masonry that they can smack each other with — anything that they haven’t already pulverized. Finally, Superman places Zod in a headlock before he is, we are given to understand, “forced” to snap Zod’s neck, thus saving a mixed-race family from dying by his flaming heat vision.

This act of killing — whether you see it as justified or not — is the final meaningful action of the movie and the inference is that Zod’s death leads to every problem in the story being solved. Superman is angry at this idea, and he should be. What this movie is telling us, or rather, what it is begging us to validate, is that any extreme action is justified — even the destruction of our own homes and cities — so long as we kill the bad guy.

Man Of Steel (2013)

“A good death is its own reward,” not one, but two characters say in this movie, and this is the Hollywood screenwriter’s current mantra. Consider how much creative energy is directed by writers in trying to find a new way to kill, and a new way to blow things up.

What is really scary is what this movie says about the filmmakers, and what it says about us if we applaud it — and remember, by simply paying to see these movies of destruction, like Man of Steel, Pacific Rim and World War Z, we are applauding them. In the Hollywood economy, critical acclaim (such as this blog) count for nothing: every ticket is a vote for more of the same and so far Man of Steel has taken in 620 USD worldwide, and a sequel has just been announced.

IMAGINE A BOOT

While I was watching the fight scenes, I was reminded of a famous quote in George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four — the one about the boot. I went back and looked it up and was surprised at how accurate Orwell’s vision of the future, once again, proves to be. In it the character of O’Brien describes the future:

“There will be no curiosity, no enjoyment of the process of life. All competing pleasures will be destroyed. But always — do not forget this, Winston — always there will be the intoxication of power, constantly increasing and constantly growing subtler. Always, at every moment, there will be the thrill of victory, the sensation of trampling on an enemy who is helpless. If you want a picture of the future, imagine a boot stamping on a human face — forever.”

The makers of Man of Steel are not curious about life, nor do they display any enjoyment of it, as the makers of Superman: The Movie obviously did. Instead, they are intoxicated by a power which always increases (except this one does not grow subtler). The response it demands of us is the thrill of victory and the vilification of a two-dimensional enemy.

That is what Man of Steel is — a metaphorical boot unremittingly stamping on the face of all that is good in humanity. If the movie is a syllogism, the last scene is its conclusion and every scene before that is a proposition. That means that every contrivance of character and event that the filmmakers made served only to create a situation where Superman could create maximum destruction and the killing with intent of an enemy.

This is the core message of Man of Steel: no temple is sacred in the pursuit of the destruction of our enemies. Unlike my generation, this one will grow up with a Superman who kills.

The Man of Tomorrow welcomes you to the future.

Art by Curt Swan

APOLOGIA

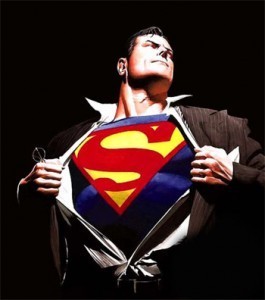

Art by Alex Ross

It doesn’t have to be as bad as that. Superman comics are still very good, often very moral, and I encourage you to read them, especially Grant Morrison’s All Star Superman, undoubtedly the most intelligent Superman stories, and also Superman: Birthright, the best of the modern retellings of Superman’s origins.

People also seem very ready to forget how good the first few seasons of the Smallville TV show were. For moral rectitude, John Schneider’s Pa Kent is pitch-perfect, and Michael Rosenbaum’s Lex Luthor is delightfully ambiguous.

This summer’s blockbuster movies haven’t been all bad — although they have all been violent. The best scene of them all was the “barrel of monkeys” sequence in Iron Man 3, which was an action scene that didn’t show Iron Man against a bad guy, but only Iron Man against the laws of physics. Also, Star Trek: Into Darkness was a movie premised on the idea that killing our enemies may not solve all our problems.

But seriously, if you haven’t done so, buy a copy of Superman: The Movie. It’s a complete delight from start to finish. It is full of emotion, tension, and humour, and not once does Superman inflict violence on anyone or anything.

June 5, 2013

Rewriting Poetry III

So it’s been a while since I last posted on my probably insane attempt to rewrite a Medieval poem. This is because, looking over what I’ve written, I’ve been unsatisfied about its length. I think I mentioned two or three stanzas? It’s all very interesting as an exercise, but having to struggle through it is pretty demanding on the reader, and to stick it in the middle of an adventure fantasy novel is even moreso. Having had some time and perspective, I think I’m getting too wrapped up in the creative challenge of recasting the poem, and I’m not doing what’s best for the poem itself (not to mention the book it has to fit in).

So I’ve decided to cut the poem right the way back in terms of what it’s actually saying. Less is more. From the numerous variations in the poem, it looks fairly obvious that someone once had a clever little idea for a short poem that got to be quite popular, and then a few hundred years later someone else read or heard it and really ran with the idea, probably in order to impress a patron.

All that aside, art has to be functional, and the form has to fit the function. What I want to convey is one idea coming from one character which is: we are all mortal, material beings and, in the long view, nothing more than clumps of earth that get to move around for a short time. This in mind, and keeping the rhymes I’ve developed, I come up with this:

Earth that walks on earth, must from the earth earth grow

Earth that earth may eat, so earth in earth earth sows.

But if the earth the earth won’t eat, then earth in earth shall go:

A hole in earth shall other earth make, then earth in earth earth stows.

Which is pretty durned close to what we started with, only going with food rather than treasure, which was a little more obscure (and harder to rhyme anyway). It’s still pretty confusing, so I’ve decided to explain it away as a riddle. Not all riddles have one-word answers, some of them describe a scene in a confusing way and demand the explanation from the listener (like the “Two legs sat on four legs” riddle from Tolkien’s The Hobbit.) And quite possibly that’s what the first poem was anyway.

So I’ll pop that scene in the book along with the ‘answer’. It’s a pretty long way to go for only fifty words (and only twenty-four of them different to each other), but that’s poetry for you!

At least that’s been my experience whenever I’ve written it.

May 23, 2013

The Words We Mispronounce

We’ve all got words that we’ve misapprehended. Words that, when young, we’ve seen written down and tried to sound out and come away with completely the wrong sounding of. As a child growing up and spending way more time reading than I was talking to anybody, I had lots of these — so many that I never became embarrassed and accepted the corrections as a matter of course in nearly any conversation. But there was one big disappointment in one word that definitely sounded better in my head than in real life:

“Rendezvous”.

The way that I grew up saying that word, privately and in my head, was ‘REN-dez-VUSS’. From the context I saw the word in it was obvious it meant a meeting, or a meeting place, but there was something in the feel of the word. Phonetically, is sounded most like ‘reckless’, something haphazard. Saying it gave a staccato effect, like gunfire answering gunfire. There was danger and uncertainty in the word that painted a picture of men on horseback racing down a hill, guns drawn, trying to reach a farmstead fortress, or head someone off at a ubiquitous pass.

[image error]

“Ride on to the rendezvous!”

So imagine my disappointment when I found that the word was actually pronounced as a casual, lilting ‘RON-day-voo…” with the last syllable trailing off non-committaly. It was pronounced nothing like what it looked, and in fact for years I openly believed that there were two different words that meant the same thing and probably would have tried to correct anyone who challenged me on the point.

‘Ron-day-voooo…’ It’s a slow, declining slide of stresses that peter out into a sigh of ambivalence. Its accompanying gesture would be a shrug or a limp hand movement. It’s mature and restrained, almost repressed sounding — far more Noel Coward than Zane Grey. Even after all this time I miss the hurtling, suspenseful ren-dez-vuss! of my childhood.

May 16, 2013

A Scene in a Bookstore

Me: Hello, I’m look for the ‘Palliser Novels’ by Anthony Trollope in a boxed set, or maybe an omnibus edition?

Clerk 1: That’s not my section. Mary — Trollope, boxed set?

Clerk 2: No, not in a boxed set. We’ve never sold any Trollope boxed sets.

Me: But I saw one here a few weeks ago. It was all six of the Palliser Novels.

Clerk 2: You’re mistaken, you must have seen that at another bookstore.

Me: No, I’m certain it was this one…

Clerk: Well, Trollope’s in my section and I buy all the books. We’ve never sold any six book box sets of Joanna Trollope.

Me: No, Anthony Trollope. Anthony. He wrote the Palliser Novels — Anthony Trollope.

Clerk 2: That doesn’t sound familiar. Have you checked the shelf?

Me: Yes. There’s lots of them there, but I’m looking for the Palliser box set.

Clerk 2: Really?

Me: He’s — yes. They’re right there. He’s — look. That whole shelf in Classics.

Clerk 2: Oh. That’s not my section.

April 11, 2013

The Fearful Gates – Cover Preview

April 1, 2013

The Redraft — Book 3 preview

Here’s a little glimpse into my working process — perhaps a little too intimate a glimpse. I never show anyone my early drafts… not my editors, not my family, not my friends who try to bribe me to try to know what happens next. But I really like redrafting — it’s an opportunity to make every- and anything better, and to add a little bit of awesome.

But here you can see the uncorrected, un-awesome-d rough draft pages along with my messy annotations and corrections. The changes I eventually make may not be these ones, and this will certainly not be the last draft I make. This is the prologue to The Ancient Earth Book 3 — The Fearful Gates — warts and all (with added warts).

March 21, 2013

The Best Shakespeare Adaptations

I’m a nut for Shakespeare, even though I rarely read it. Shakespeare wrote his plays to be performed, and so over the years I’ve tried to keep track of the best adaptations, and this is what I’ve collected, in no particular order.

A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1999, Michael Hoffman)

This is one of my least favorite plays, but the movie is simply brilliant. The casting may seem a bit strange at first, but it’s inspired. The actors really spark off of each other, particularly the four lovers. The one who really carries it though is Kevin Kline as Bottom. The donkey-acting with prosthetics is neither here nor there, but he puts in a masterwork in the Pyramus and Thisbe set piece at the end of the movie which is genuinely funny and stays completely on text.

This is one of my least favorite plays, but the movie is simply brilliant. The casting may seem a bit strange at first, but it’s inspired. The actors really spark off of each other, particularly the four lovers. The one who really carries it though is Kevin Kline as Bottom. The donkey-acting with prosthetics is neither here nor there, but he puts in a masterwork in the Pyramus and Thisbe set piece at the end of the movie which is genuinely funny and stays completely on text.

Much Ado About Nothing (1993, Kenneth Branagh)

I’ll be up front — Kenneth Branagh is going to crop up in this list more than a few times. He has tons of experience in Shakespeare, he founded his own company The Renaissance Theatre Company and was instrumental (along with others such as Richard Eyre) for developing Shakespeare performance into its modern form, removing a lot of the formality that actors and directors such as Laurence Olivier and Orson Welles approached it with. This is one of my favorites of his. It’s a straightforward presentation which nonetheless sparkles through its performances, particularly Michael Keaton and Emma Thompson.

I’ll be up front — Kenneth Branagh is going to crop up in this list more than a few times. He has tons of experience in Shakespeare, he founded his own company The Renaissance Theatre Company and was instrumental (along with others such as Richard Eyre) for developing Shakespeare performance into its modern form, removing a lot of the formality that actors and directors such as Laurence Olivier and Orson Welles approached it with. This is one of my favorites of his. It’s a straightforward presentation which nonetheless sparkles through its performances, particularly Michael Keaton and Emma Thompson.

As You Like It (2006, Kenneth Branagh)

I had trouble with As You Like it before I saw this version of it. It’s an oddly paced play and has all of the stereotypes about separations and cross-dressing. The movie is well conceived and the Imperial Japan setting gives it a fresh vibe. Also: ninjas. Ninjas in Shakespeare. How awesome is that?

I had trouble with As You Like it before I saw this version of it. It’s an oddly paced play and has all of the stereotypes about separations and cross-dressing. The movie is well conceived and the Imperial Japan setting gives it a fresh vibe. Also: ninjas. Ninjas in Shakespeare. How awesome is that?

Richard II – Hollow Crown, Episode 1 (2012, Rupert Goold)

This is one of my favorite plays, but I have never seen it well performed until last year. The Second Henriad is wonderful when contemplated as a long storyline, so I’m very glad that they were all adapted at the same time. Ben Wishaw gives a powerhouse portrayal of the fickle Richard who is almost completely ruled by whimsy. He is pitch-perfect throughout – and the scene with the monkey is profoundly outrageous.

This is one of my favorite plays, but I have never seen it well performed until last year. The Second Henriad is wonderful when contemplated as a long storyline, so I’m very glad that they were all adapted at the same time. Ben Wishaw gives a powerhouse portrayal of the fickle Richard who is almost completely ruled by whimsy. He is pitch-perfect throughout – and the scene with the monkey is profoundly outrageous.

Henry V (1989, Kenneth Branagh)

I remember watching this in school and just not getting it. At all. It was only after I’d watched his Hamlet a few times that I understood that the words people were saying could actually be understood and I came back to this and understood its brilliance. It’s powerful, but with such a light hand. Obviously a low-budget production, it is unhindered by empty, dimly-lit sets. The editing is excellent and the edits Branagh makes to the script are perfectly judged. The muddy battle at the end is one of my top movie moments ever, and Branagh the song, Non Nobis, Domine, which plays as Branagh triumphantly walks across a desolate battlefield (carrying a young Christian Bale!) is incredibly moving.

I remember watching this in school and just not getting it. At all. It was only after I’d watched his Hamlet a few times that I understood that the words people were saying could actually be understood and I came back to this and understood its brilliance. It’s powerful, but with such a light hand. Obviously a low-budget production, it is unhindered by empty, dimly-lit sets. The editing is excellent and the edits Branagh makes to the script are perfectly judged. The muddy battle at the end is one of my top movie moments ever, and Branagh the song, Non Nobis, Domine, which plays as Branagh triumphantly walks across a desolate battlefield (carrying a young Christian Bale!) is incredibly moving.

King Lear – Ran (1985, Akira Kurosawa)

This is not in my top five of Kurosawa movies, but it is the best Lear adaptation I’ve seen. Kurosawa is one of those special and rare directors who can deliver spectacle, and always puts at least one thing in each movie that no one has ever seen before. He was a famous Shakespeare fan himself and he made this labor of love at the age of 75. You don’t enjoy Shakespeare’s text with this movie, but visually it will be like little else you’ve ever seen.

This is not in my top five of Kurosawa movies, but it is the best Lear adaptation I’ve seen. Kurosawa is one of those special and rare directors who can deliver spectacle, and always puts at least one thing in each movie that no one has ever seen before. He was a famous Shakespeare fan himself and he made this labor of love at the age of 75. You don’t enjoy Shakespeare’s text with this movie, but visually it will be like little else you’ve ever seen.

Macbeth – Throne of Blood (1957, Akira Kurosawa)

This is Kurosawa’s first attempt at Shakespeare, and he plays it fairly loose. It’s mostly a reinterpretation of the plot while using the same themes and characters. Not so high in fidelity, but completely riveting — as anything with the immeasurable Toshiro Mifune is — and the small departures are not for no reason. I’ve seen it just a couple times, but every shot of the arrow scene at the end is engraved on my brain.

This is Kurosawa’s first attempt at Shakespeare, and he plays it fairly loose. It’s mostly a reinterpretation of the plot while using the same themes and characters. Not so high in fidelity, but completely riveting — as anything with the immeasurable Toshiro Mifune is — and the small departures are not for no reason. I’ve seen it just a couple times, but every shot of the arrow scene at the end is engraved on my brain.

Othello – O (2001, Tim Blake Nelson)

This movie is everything that a modern Shakespeare retelling should be. Transferring the setting into a private high school is a brilliant move, heightening both drama and tension. The plot so tightly follows Shakespeare’s original, you can almost believe it’s a scene-by-scene adaptation, but the invented material — particularly the relationship between Hugo (Iago) and his father. There are some great, intense performances, particularly by Josh Hartnett. Julia Stiles is also commendable.

This movie is everything that a modern Shakespeare retelling should be. Transferring the setting into a private high school is a brilliant move, heightening both drama and tension. The plot so tightly follows Shakespeare’s original, you can almost believe it’s a scene-by-scene adaptation, but the invented material — particularly the relationship between Hugo (Iago) and his father. There are some great, intense performances, particularly by Josh Hartnett. Julia Stiles is also commendable.

Hamlet (1996, Kennth Branagh)

You never lose your love of the work that opened Shakespeare up to you, and that’s what this was for me. I was so surprised that I was actually catching the gist of what was happening in the scenes for the first time — I could actually follow the plot, mostly. And that credit is due to Branagh — and all the more since it’s completely unabridged (which I think I read was the first movie adaptation of Hamlet to do so). It’s wonderfully directed and shot on 70mm film to give incredible panorama and depth to the scenes.

You never lose your love of the work that opened Shakespeare up to you, and that’s what this was for me. I was so surprised that I was actually catching the gist of what was happening in the scenes for the first time — I could actually follow the plot, mostly. And that credit is due to Branagh — and all the more since it’s completely unabridged (which I think I read was the first movie adaptation of Hamlet to do so). It’s wonderfully directed and shot on 70mm film to give incredible panorama and depth to the scenes.

Romeo and Juliet – Romeo + Juliet (1996, Baz Lurman)

Romeo and Juliet is a pretty overexposed play, and this is the best edition of it. It’s flashy and over-the-top, but brought Shakespeare to a whole new generation of moody teenagers. Nice soundtrack.

Romeo and Juliet is a pretty overexposed play, and this is the best edition of it. It’s flashy and over-the-top, but brought Shakespeare to a whole new generation of moody teenagers. Nice soundtrack.

Macbeth – Shakespeare Retold (2006, Mark Brozel)

The BBC Shakespeare Retold series was pretty good. Not all of them were hits, but The Taming of the Shrew worked well (Shirley Henderson needs to headline more stuff), and then there was Macbeth. James McAvoy plays a chef working in a celebrity cook’s star restaurant, making the dishes that his boss takes all the credit for. It’s a fast, intelligent, and emotional rollercoaster ride which doesn’t disappoint even if you know exactly what’s going to happen. And McAvoy butchers a pig’s head live on camera which, bizarrely, completely ties into the show’s theme.

The BBC Shakespeare Retold series was pretty good. Not all of them were hits, but The Taming of the Shrew worked well (Shirley Henderson needs to headline more stuff), and then there was Macbeth. James McAvoy plays a chef working in a celebrity cook’s star restaurant, making the dishes that his boss takes all the credit for. It’s a fast, intelligent, and emotional rollercoaster ride which doesn’t disappoint even if you know exactly what’s going to happen. And McAvoy butchers a pig’s head live on camera which, bizarrely, completely ties into the show’s theme.

Richard III (1995, Richard Loncraine)

There’s a lot about this adaptation that wouldn’t seem to work, on the face of it, but it all manages to hang together. Mostly because of Ian McKellan, of course, but the European civil war setting gives it a lively ambiance. Definitely one to put on your list.

There’s a lot about this adaptation that wouldn’t seem to work, on the face of it, but it all manages to hang together. Mostly because of Ian McKellan, of course, but the European civil war setting gives it a lively ambiance. Definitely one to put on your list.

The Taming of the Shrew – 10 Things I Hate About You (1999, Gil Junger)

You wouldn’t think that Shakespeare would make a good light teen rom-com, but it totally does. It all works fantastically. It is impeccably cast and rolls right along. If you don’t take it too seriously, it’s really quite delightful.

You wouldn’t think that Shakespeare would make a good light teen rom-com, but it totally does. It all works fantastically. It is impeccably cast and rolls right along. If you don’t take it too seriously, it’s really quite delightful.

Titus Andronicus – Titus (1999, Julie Taymor)

This film suffers from a little too much artism. It’s grandly staged and the actors really trumpet out their performances, but it manages to stay just shy of way-too-much. It’s a good way to see an underperformed play. It stars Anthony Hopkins and he does a solid job.

This film suffers from a little too much artism. It’s grandly staged and the actors really trumpet out their performances, but it manages to stay just shy of way-too-much. It’s a good way to see an underperformed play. It stars Anthony Hopkins and he does a solid job.

The Merchant of Venice (2004, Michael Radford)

A by-the-numbers adaptation, but a decent one nonetheless.

A by-the-numbers adaptation, but a decent one nonetheless.

That is all.

Coriolanus (2011, Ralph Fiennes)

I equivocated in including this one because at the moment it’s the play I love the most out of all of his, and I’m still not sure what I think about this take on it. Fiennes’ earnestness is laudable, but the tone never lets up; it needs a lighter touch in certain areas. Still, Coriolanus is awesome.

I equivocated in including this one because at the moment it’s the play I love the most out of all of his, and I’m still not sure what I think about this take on it. Fiennes’ earnestness is laudable, but the tone never lets up; it needs a lighter touch in certain areas. Still, Coriolanus is awesome.

The Tempest – The Forbidden Planet (1957, Fred M Wilcox)

I’m going to round the list out with what is truly a cinematic cornerstone – Forbidden Planet! The movie that gave us Robby the Robot. Again, like the best modern retellings, it works just as well if you have no knowledge of the play whatsoever, as I didn’t when I saw it at the age of eight years old. That such a story can make an under-ten be completely fixated for an hour and half shows the immortal power of Shakespeare’s writings. In addition: Leslie Nielson. Need I say more?

I’m going to round the list out with what is truly a cinematic cornerstone – Forbidden Planet! The movie that gave us Robby the Robot. Again, like the best modern retellings, it works just as well if you have no knowledge of the play whatsoever, as I didn’t when I saw it at the age of eight years old. That such a story can make an under-ten be completely fixated for an hour and half shows the immortal power of Shakespeare’s writings. In addition: Leslie Nielson. Need I say more?

March 20, 2013

Eat This Blog

I guest blogged on shawnsmallstories.com today. Read it here.

Ross Lawhead's Blog

- Ross Lawhead's profile

- 31 followers