Ross Lawhead's Blog, page 12

January 1, 2012

Books I Read in 2011

The annual list, in the order of reading:

Doctor Who: Nuclear Time, Oli Smith

Silas Marner, George Elliot

The Honorary Consul, Graham Greene

Parrot and Olivier in America, Peter Carey

The Quiet American, Graham Greene

The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, Muriel Spark

The Confession, John Grisham

Horns, Joe Hill

The Dark Night of the Soul, St. John of the Cross

Mere Anarchy, Woody Allen

The Making of Doctor Who, Malcolm Hulke & Terrence Dicks

Tarzan the Ape Man, Edgar Rice Burroughs

We Have Always Lived in the Castle, Shirley Jackson

Doctor Syn: A Tale of Romney Marsh, Russell Thorndyke

The Tenth Man, Graham Greene

The Complete Mr Mulliner Omnibus, P G Wodehouse

The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch, Philip K Dick

The Bone House, Stephen Lawhead

The Uses of Diversity, G K Chesterton

Longitude, Dava Sobel

Supergods, Grant Morrison

The Woman in Black, Susan Hill

A Game of Thrones, George R R Martin

Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy, John LeCarre

Espresso Tales, Alexander McCall-Smith

A Clash of Kings, George R R Martin

Snuff, Terry Pratchett

What We Believe But Cannot Prove, ed. John Brockman

The Silent Stars Go By, Dan Abnett

I tried a bunch of new writers this year — Elliot, Spark, Burroughs, Jackson, Thorndyke, Sobel, Martin, and LeCarre. I enjoyed them all, but Jackson, Martin, and LeCarre were particular delights. I hadn't heard much of Shirley Jackson before I picked her book up, but now I fully anticipate reading her complete works in the next few years. For years I'd been calling John LeCarre my favourite author that I've never read, and he didn't disappoint. It was a rich, quick and entertaining read.

Martin was a bit of a surprise. I downloaded the preview on my Kindle and was impressed with how easily it read and how bold the plot was. I had mostly given up on high fantasy reading, but this turned my mind around and I am slightly ashamed at having taken a couple swipes at the sub-genre in REALMS. (But only ever so slightly.) It was made more fun by the fact that several of my friends are reading the same series; it's enjoyable to read as a group.

Grant Morrison's Supergods was quite an experience. It starts out as a superhero analytical retrospective, and turns into a confidential tell-all about life as a drugged-up anarchistic conjurer.

This was the first year that I read anything on Kindle, and I really enjoyed it. It's a great and versatile platform and I wax lyrical on its future of the publishing industry here.

November 29, 2011

On Being Reviewed

As I see it, there are two types of witers in this world: those that read their reviews, and those that tell people that they don't.

Ask just about anybody, and they'll tell you "don't read your reviews." It's the one thing that everyone seems to know about writing, and really, it's not bad advice. Good ones can make you inflated, bad ones can make you mad, mediocre ones will make you annoyed – and none of them will make you more productive.

However, it's impractical advice. It's not that the temptation is truly overwhelming, because it is, but writers don't do what they do in a bubble, and we need feedback. Also, if there's one thing publishers these days really drill into you, it's that self-promotion is as important (subtext: more important) as the actual writing of the book, and so it's in your best interest to plug into all of this stuff in order to create a 'presence'. Which I find odd, since if novelists were any good at creating a presence, then they would most likely be actors. Or musicians.

Anyway. Reviews are one type of feedback, although they are a skewed form of feedback, and in the case of online reviews, often completely warped. A review is seen by reviewers as a performance art – an act of creation comparable to writing the novel itself - and in a bad reviewer, it's that performance aspect which can threaten to take over. Often, these impulse can be quashed by a good editor. Online, these impulses run rampant with little or no filter at all.

That said, we all have our opinions. Heck, I've written an online review or two in my time, so I guess I can say that I know what I'm talking about. The inherent flaw in reviews is obvious, and it's the reason that I've shied away from reading them, always, even before I became a writer. There's just no accounting for taste. It's as simple as that. Unless you can find that reviewer whose tastes almost completely complement yours (it's not impossible – my tastes in film are almost identical to Jonathan Ross'), then I would question your motives in reading a review at all, especially for an art form as intimately experienced as a novel. I have absolutely adored so many books that have received completely dismal reviews from very respectable reviewers to now be totally convinced that any bad review can be disregarded completely. Good reviews, probably less so, but the logic still stands. There's no accounting for taste. Heck, some people claim to enjoy John Fowles (but we all know that's impossible).

Anyway, that's all prologue. What I wanted to share was the inside of what it's like to be reviewed.

First off, it's a thrill, no doubt. After all, people are talking about your book! The thing that's been inside your head so long, and which was so hard to get on paper, is out there, and people are reading it! In the first couple weeks, many more good reviews come in than bad ones, which gives you a false confidence. What's happening is that the people who enjoy the book are reading it quickly, and those that don't like it, quite naturally, are reading it slowly. But even when the bad ones come in, it's still a thrill because after all, people are still reading it, and if you're the sort of writer that I am, then you're kind of glad that not everyone likes it, because you didn't set out to write a lowest-common-denominator book that could be understood by every casual reader. You wrote some DEEP stuff that really needs to be read a couple times to be appreciated, or even understood. That's what you tell yourself.

Then the niggles start, and this is what your friends had been trying to protect you from. (So don't go complaining to them.) What niggles initially is just the plain laziness of most of the reviews. 67% of the time, they just copy and paste the synopsis on the publisher's website with a paragraph tacked on the end and a link to the same review that they posted on Amazon.

But that niggle soon pales in comparison to the larger one of people just plain getting things wrong. This one is very puzzling, and annoying, since it buzzes around in your head like a fly that just won't go out the open window you're shooing it towards. What book, exactly, are people reading? My very first review from Publishers Weekly contained two factual errors which betrayed the reviewer not having read past, most likely, chapter three. Here's a quick list of things people have gotten wrong about my first book. I'm not printing them as a vain attempt at trying to set the record straight, these are just convenient examples:

1 - The titular Realm Thereunder is another world (akin to Narnia or Middle Earth). It most explicitly is not, it's this one, and I make a point of saying this repeatedly in the book.

2 – The names and lore are Celtic (akin to the influences in my dad's books). They most explicitly are not, they're Anglo-Saxon, and I make a point of saying this repeatedly in the book.

3 – The book is intended for teenagers. It most explicitly is not, and the publisher made a point of saying this on the back of the book.

4 – The book is a stand alone title, and not part of a series. It most explicitly is not, and the publisher made a point of saying this on the FRONT, BACK, and SPINE of the book.

5 – The book is a thriller. I don't get this one. Maybe we just jumped the wrong way on the whole 'should there be people running on the cover' issue.

6 - SPOILER ALERT. The good guys win in the end. They most explicitly do not, and I make a point of saying that, repeatedly, in the last two chapters of the book. Obviously, the reader was just lazy. Or maybe jaded from too many Ben10 episodes. But I hope it was lazy, for their sake.

Those are the top few, but durnnit if they don't keep on piling up.

Quick on the heels of the niggles are the major annoyances. These are few, but significant. They seem important because, bizzarely, you think you can do something about them. The major annoyances are the patterns of commentary that form to illustrate complete disconnects between you and the reader, which are mostly circumstantial. Nonetheless, they make you question not only continuing as a writer, but also as a member of species: sapiens, genus: homo. My publisher has an initiative in which any blogger can request my book free of charge, only for the asking of it, provided they review it. It doesn't have to be a favourable review, it just has to be written. This has been… instructive, since it has exposed my book to a whole spectrum of people who, by rights, probably don't have any business even hearing about it.

The negative reviews have all fallen into two categories (regardless of how many of the above niggles are mixed in), which illustrate my two disconnects with my reviewers.

1 – They don't enjoy the Fantasy genre. At a guess, 80% of my negative reviews start this way. Full marks for taking a chance , and I don't want to discourage that in the slightest. However, in most of these reviews they go on to say that if you do like fantasy, then you'll probably like my book — and then they give it a two star Amazon review. Where's the sense? One guy apparently asked for it by accident and spent the whole review literally begging my publisher to let him out of his obligation to read it. Of course, his review is still online.

2 – The good characters aren't good enough, the bad characters aren't bad enough. It may be the door I've chosen to enter through into the Fantasy party that gets me this response. Secretly, I'm quite pleased about this one. I know that there's a time and place for unnuanced unrealistic fiction (I just can't think what it is right now). These guys usually try to enforce some sort of personal morality rating as to who the book is appropriate for, which is really just warped. Some people sound quite upset, and in a way, I do feel bad about opening a little window of doubt into their small, black and white world, but I swear, it's only to let some light in as well. Not to make things grey, but to make them colourful.

These are the two main problems I've been grinding my gears on, and really I shouldn't, because it's completely out of my control and probably isn't important in the least. There's a part of you that does think, though 'If only I could do X, and explain Y, then just about everybody who reads my book would love it…' but that's almost certainly not true. It's frustrating to be misunderstood, especially when you've expended every pain to be understood, but I think that's par for the course.

There have been a very small percentage of reviews (two, so far) in which the reviewers have been familiar with the fantasy genre and didn't like the book (and also seemed to possess decent reading comprehension levels), and to those people, I am genuinely regretful of taking up their time, and honestly intend to strive harder in the future to please. Your intelligent criticism has been noted.

But to the rest of you: "huh?"

In summation: don't read your reviews. However, that being impossible, do read them, but don't get mad. But that also being impossible, do get mad, but tell yourself that it happens to everyone. And always remember, you've written a fricken book, man. You've added a brick to the cathedral of literature that no one can ever possibly remove.

Even if they wish they could.

October 1, 2011

Entering the BONE HOUSE – Lawhead on Lawhead

The Bone House is something of a rarity, not just in itself as a piece of literature, but also in its conception. More and more, recently, I've read SF/F books which were just a hair's breadth and a typeface change from being a screenplay. When Hollywood comes calling, they bring a lot of money to the table, and with popular interests taking more and more tentative steps into the literary Fantasy world (Lord of the Rings, The Narnia Chronicles Eragon, A Game of Thrones, Inkheart, to mention only a few of a dozen mid-high earning successes) it's becoming less common for a writer not to produce a book without at least one eye to the west, much less to outrightly defy Big Screen adaptability.

The Bone House is something of a rarity, not just in itself as a piece of literature, but also in its conception. More and more, recently, I've read SF/F books which were just a hair's breadth and a typeface change from being a screenplay. When Hollywood comes calling, they bring a lot of money to the table, and with popular interests taking more and more tentative steps into the literary Fantasy world (Lord of the Rings, The Narnia Chronicles Eragon, A Game of Thrones, Inkheart, to mention only a few of a dozen mid-high earning successes) it's becoming less common for a writer not to produce a book without at least one eye to the west, much less to outrightly defy Big Screen adaptability.

The BRIGHT EMPIRES pentalogy is just such a defiant series, if ever there was one. While I can pretty well guarantee that it wasn't written as a deliberate snub of the growing number of screenplay-esque manuscripts that get covered and bound, it's very hard to think of what else could be added to make it so. There is a clockwork-like complexity and rhythm to the narrative that completely staggers expectation. Minor characters are suddenly found to be integral to larger events around them. Major characters appear and then pass out abruptly, carried away on their own larger courses.

Which bridges to the second aspect of its rarity, which is that it is not the normal course for career writers to become more inventive and more risky as their careers progress, especially entering their third professional decade. The obvious exceptions to this are, of course, the great giants of the genre. My dad's career started in pure fantasy with the DRAGON KING TRILOGY. After a few Speculative Fiction works, he walked along the Fantasy/Historical lines, sometimes dipping more into one (the SONG OF ALBION series) and sometimes more into the other (BYZANTIUM and the CELTIC CRUSADES), and sometimes mixing them both into what should rightly be termed Historical Fantasy (the PENDRAGON CYCLE and KING RAVEN). This, his latest series however, is, almost literally, worlds away from his previous works in what I think should be called Science Fantasy. Ursula Le Guinn once said that the difference between Fantasy and Science Fiction was that Fantasy is based on the impossible, while SF is based on the possible. And the ideas that my dad explores this latest book — alternate timelines and shared social consciousness are foremost in mind — are all concepts currently being very seriously discussed by very serious men in some seriously serious universities.

Real-world scientist and 'omnimath' Thomas Young is a very active character in Bone House

What is striking most to me in the work — and is reflected in the many piles of research material at my parent's house that contain books that have 'quantum', 'dimensions', and 'universes' in the titles — is the bleeding-edge theoretical physics that's been very deftly mixed into the story which strengthens but never overpowers the plot. Just how important and how as-to-now underplayed this framework is will become apparent in the next three volumes. Alternate history tales are not unknown, but it is rare that they do not come across as gimicky, and even rarer to be presented with so many different alternate histories in one story.

The history angle itself is something new to be appreciated for Stephen Lawhead fans. While he has made a good name for himself in the historical fiction trade, two of the eras he has chosen to dip into in this work — 1600s Europe, and Ancient Egypt — are among the hardest to write about simply because so much has been written about them already. Where time periods edging closer and closer to the prehistoric are fairly easy to write about, time periods where there is quite a lot already known (especially with the C17th very much in the public consciousness with TV shows like The Tudors on) are a mind-breaking minefield of historical detail. And yet dad manages to saunter effortlessly back and forth between them in the most carefree, almost absent-minded manner, and with nary a lace ruff or sandal strap out of place.

Dad

If the Bone House, and the ANCIENT EMPIRES as a whole, has a criticism, it's that its plot trajectory and pacing doesn't fall into the lulled cadence of typically monotonous popular fiction, and so its irregular tempo can be very jarring to the generally soporous reader. It feels arrhythmic. Atonal. But that's only if you try to make sense of its rises and falls according to the common current conventions. If only you sit back and enjoy the experience of a new tale told in an original and unconventional way, then you will almost instantly be swept away by its magnificence.

June 22, 2011

The Future of Publishing

Many of you will now have been made aware of the success of John Locke, the first independent (i.e. self-epublished) writer to sell over 1,000,000 books in the Amazon Kindle format. Many people are wondering how they feel about this news, and I'm gratified to find that there isn't the universal decrying of the 'death of culture' that I had expected when this news was to, inevitably, in some form or another, break.

Many of you will now have been made aware of the success of John Locke, the first independent (i.e. self-epublished) writer to sell over 1,000,000 books in the Amazon Kindle format. Many people are wondering how they feel about this news, and I'm gratified to find that there isn't the universal decrying of the 'death of culture' that I had expected when this news was to, inevitably, in some form or another, break.

These are the thought from a writer and industry insider, currently under contract and anticipating the print launch of his first novel.

I think it's great. This is only just the start of a boom for efiction, and a year from now, the list of 1 million sellers will be in the high double digits. This is the best way forward for the industry since it moves the balance of power back in favour of the writers and the readers who will decide first what they are passionate about writing, and next what they are passionate about reading.

In the last twenty years we've seen the decision for what comes out of a publishing house move out of the hands of editorial and into the hands of marketing. I was last published in 2003, and my next project is coming out in this year, 2011. In those eight years, I've had to suffer many rejections from dozens of publishers and editors who really enjoyed and were excited my project proposals, but on the advice of marketing decided to turn them down, not being judged market viable. Whereas before marketing would receive their marching orders from the publisher and editorial to sell what they believed to be art of a good quality, it is now market analysts and salesmen who are calling the tunes that the whole industry must dance to — writers and readers alike.

It's probably not the worst system, but it's not ideal. Occasionally you would hear tales of authors going against this system, somehow beating the odds through self-publication (G P Taylor comes to mind, the vicar who sold his motorcycle to print the first 300 copies of the very excellent Shadowmancer), or sheer bloody-mindedness (J K Rowling's Harry Potter was apparently rejected by everyone except the 8 year-old daughter of the publisher that eventually signed her), but they were the gross exceptions.

Epublishing has the potential to turn these exceptions into the rules. I believe I am the last generation of authors to operate under the system that's been in place for, roughly speaking, the last 150 years, since just after the time of Dickens and Dumas.

This isn't the first innovation to hit the publishing industry. Printing books these last ten years has been cheaper than ever. Computers mean that plates no longer have to be hand type-set. Printing on demand, or 'index printing', has been in place for almost fifteen years now, meaning that books on backlist can be very cheaply printed and shipped out without costly storage considerations. Books are just kept on file. In the last 30 years, the cost of actually manufacturing a book has dropped at least 50%, and yet this has not been reflected in the money given to the creators of the art. [NB: At the time of the transition away for hand-set type, a group of writers came together to ask that, by submitting their work on computer disks they were effectively setting their own type, and a monetary bonus should be considered for this, they were roundly ignored.]

All of which is to say that we shouldn't feel too sorry for the publishers who have been riding high on a wave that by all rights should have crashed long before now. That's not to say that they've been living fat and lazy off of it. There is very much needful work that they do in terms of quality control and promotion that is very valuable to the industry, but it is characteristic of the rigidity in the industry's thought which will destroy them if they continue as they have and see epublishing just as something that must be weathered instead of something that must be adapted to.

Because make no mistake: this isn't just an innovation, it's also a paradigm shift. It will now be up to the readers to sift and decide for themselves what they wish to read. It will be harder for them since we will likely see a fivefold increase of books on the market — and almost all of them, realistically speaking, of very poor quality. The onus of spelling and editing (what is currently often three people's job within a publisher) will fall more squarely on the creator's shoulders, and it's no light burden. Also, the marketing and business sides will be a larger consideration, and creative minds aren't always suited to such tasks, although the internet will give something back in this respect. There are even now independent book review sites that exclusively review self-published eBooks, may the Lord forever bless them, and the trend towards 'viral', where information is referred rather than sought, will enable readers to refer a book within seconds and for a new reader to buy that book, direct from the author just seconds later, for more money than they are now getting from any publisher.

So what is the future of fiction publishing, in real terms? The future, as I see it in the next 10-15 years, is that paperback sales will be gone. Good news for the rain forests. Cheap classics, airport and supermarket thrillers, holiday fiction, et al, will be replaced by ebooks. Manifest, tangible books will still be printed, but will almost exclusively be hardback and of a high quality, with good paper stock, very well illustrated, and often in limited editions. Books, in other words, that give a reading experience beyond something that can be reproduced on an eReader. Digital ink eReaders will be in colour, larger, and 1/3 of current price. Publishers themselves will take a body blow and have to decrease by 50%, but this will be nothing compared to what the bookstores, sadly, will have to endure. There may be some quick trade in second-hand books, so hopefully we'll keep some of the best independent sellers, but the reality will be that there will no longer be a bookstore in every city. (As for libraries, who can say?)

We'll lose a lot of what is the current culture of reading, but what will remain will be a passion for story and literature that has always transcended paper and ink and has been the mainstay of culture and civilisation for over 4500 years.

May 18, 2011

The New Oxford Comma

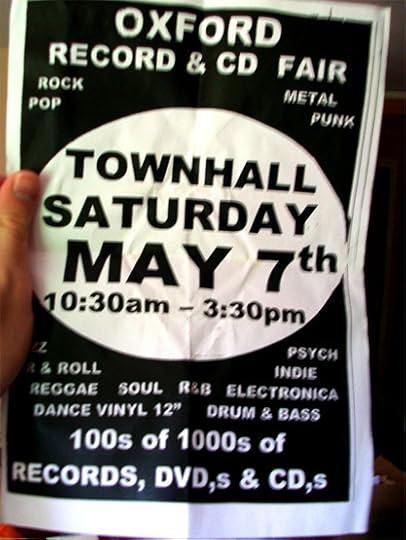

I don't want to be the guy who's always correcting people's punctuation, but sometimes someone goes too far. Take a couple seconds to study this poster that I pulled off the noticeboard at work (in the heart of Oxford, the seat of learning):

Grammar FAIL

Did you spot it? If you scanned down to the bottom line, you did. "DVD,s"? "CD,s"?

For some reason I find this heartbreaking and hilarious at the same time. I picture a skinny, pierced little music enthusiast sitting at his computer keyboard, nearly beside himself and in tears with desperation, gazing in abject confusion at the whole bucketful of punctuation that clusters on the right-hand side of his keyboard. His mind dimly recalls a hazy scene now almost twenty years in his past when he was told the rule for pluralising abbreviations, but he can't quite recall what it was. Did he even have to do anything at all? No, there must be something. The situation is complicated by the fact that these plural abbreviates are in a list as well.

A thought occurs to him that arrives with a thrill, like the call to adventure. Plural abbreviations in a list? When has that ever happened before? Never! There IS NO RULE for that! He's off the maps here — uncharted territory. Humanity may have reached this point at some point in the grammatical past, but if they did, no one remembered it, or left any markings to remember them by. There ARE no conventions here. He IS convention. The rules are whatever he makes them.

Boldly wiping the sweat from his palms, he reaches his skinny, pierced finger out and in a fit of creativity unwittingly creates the Frankensteinian abomination above.

And the tragedy is that he could have got it right if he only did what he did with "100s of 1000s" in the line above and declined from inserting any punctuation at all. That part of grammatical application is actually correct (if inelegant), and would have been correct here as well.

But such is Man.

May 10, 2011

An Afternoon in Numismatics

I feel that Oxford is the only place in the world where I would be able to do what I do. I think it's no coincidence that so much fantasy writing has come out of this city since so much within this city is literally fantastic.

I feel that Oxford is the only place in the world where I would be able to do what I do. I think it's no coincidence that so much fantasy writing has come out of this city since so much within this city is literally fantastic.

A couple months ago I started a once-a-week course at the Oxford University Continuing Education Department entitled Anglo-Saxon Culture and Society: Offa of Mercia and Alfred the Great. It's been really fun and taught me a lot about pre-Alfred Anglo-Saxon England, which I didn't know a whole lot about previously. I wish it would have been longer but today we did something that I hadn't done in any of the previous courses I've taken at "ContEd", and that is go on a field trip.

Our lecturer arranged for us to hear a talk given at the Ashmolean Museum by one of the staff of the Heberden Coin Room; which is open to the public, but by appointment only. For an hour and a half the numasmaticist (coin expert) talked on various coins found in fields and hoards all over England. He talked about sceattas and thrymsas and gold and light-gold and Pippin and Frisian mints and all sorts of incredible names, concepts, and people.

It was wonderful and I had the largest grin on my face from start to finish. He was also very generous in passing them around, and even allowed me to take a picture holding one of the coins.

The author, with coin from Offa of Mercia's reign. It is made of silver and smaller than a 5p piece (or a dime) and thinner. It bears only Offa's name and no likeness of him, although he would appear in very intricate detail on subsequent coins.

The coin I'm holding is from the reign of Offa King of Mercia, who was on the throne from 757 to 796, which makes it over 1,200 years old. It is the first British coin to be marked with the name of a king, and so is the first British coin that can be accurately dated (within about forty years, of course). It's the smallest thing, but very clearly bears the words Offa Rex on it.

A very similar coin to the one I'm holding. (Found online.)

As much as Numismatology teaches us about the past, it raises so many more questions that it makes an imaginatively-overactive mind like mine roar like a bonfire, and the good people at the Ashmolean were simply feeding the flames with questions of their own. Why was it just in the 700s that coinage was starting to be produced by British kings? It was more than a man could earn in a day, so what exactly was it used for? How was it spent? The concept of objects having a 'monetary value' would have been rather alien because the coin metal itself was the real value of it. A sliver cup, for instance, would have to be worth the weight/mass of silver coins to create it… and yet they're so small. So what, exactly, could you buy for one of them? Where did the precious gold and silver to make these coins come from? Why is Offa's name, surrounded by Arabic script, found on gold dinars in the Middle East?

It was a thrilling and heady afternoon and the good people of the Heberden Coin Room said we were welcome back any time we wished. I think next time I'll ask them what Viking money they have…

Ross Lawhead's Blog

- Ross Lawhead's profile

- 31 followers