Ross Lawhead's Blog, page 5

December 31, 2015

Books I Read In 2015

Via Advent, Shawn Small

Tales from Earthsea, Ursula Le Guin

The Worm Ouroboros, E. R. Eddison

A Plague of Demons, Kieth Laumer

The Elements of Elegance, Mark Forsyth

The Small House at Allington, Anthony Trollope

Doctor Who: Dreams of Empire, Justin Richards

Franny and Zooey, J. D. Salinger

Night Flight, Antoine De Saint-Exupery

The Colour of Magic, Terry Pratchett

Crome Yellow, Aldous Huxley

The Grand Babylon Hotel, Arnold Bennett

Pygmalion, George Bernard Shaw

Zuleika Dobson, Max Beerbohm

A Monster Calls, Patrick Ness and Siobhan Dowd

The Letter for the King, Tonke Dragt

No Plot? No Problem!, Chris Baty

The Prisoner, Thomas M Disch

A Sentimental Journey, Laurence Stern

Magnus, George Mackay Browning

Octopussy and The Living Daylights, Ian Flemming

Orlando, Virgiania Woolf

Land of the Seal-People, Duncan Williamson

Gryll Grange, Thomas Love Peacock

The Knife of Never Letting Go, Patrick Ness

The Ask and the Answer, Patrick Ness

The Shepherd’s Crown, Terry Pratchett

The Secret Garden, Frances Hodgson Burnett

The Riddle of the Sands, Erskine Childers

Eirlandia 1, Stephen Lawhead

A Series of Unfortunate Events: The Bad Beginning, Lemony Snicket

A Series of Unfortunate Events: The Reptile Room, Lemony Snicket

Monsters of Men, Patrick Ness

Wildwood, Colin Meloy

Slaughter-House Five, Kurt Vonnegut Jr

Challenges

The thing that made this year different than the others is the reading challenge I set myself of reading a Penguin a Week. This exposed me to a lot of books that I ordinarily wouldn’t have read, except that they had orange coloured covers. A Plague of Demons by Kieth Laumer and Gryll Grange by Thomas Love Peacock were two of these, but the real surprise delight was The Grand Babylon Hotel by Arnold Bennett which was astoundingly fresh and interesting, especially considering the year it was written. I was also able to cross some classics off my list. Crome Yellow by Aldous Huxley was better than expected, but Orlando by Virginia Woolf and Zuleika Dobson by Mac Beerbohm did not live up to the hype for me. The second challenge completed was the NaNoWriMo challenge (writing a 50,000 word novel in one month), which my wife and I attempted, and completed, in May. No Plot? No Problem! was written by the man who started that and was a huge help during the dark 30-40k period.

Surprises!

I discovered Patrick Ness this year and will hold up A Monster Calls as one of the top ten books of the decade. A Letter for the King by Tonke Dragt was another fun discovery — it’s a book that has been popular in Europe for forty years, but had never been translated into English until just now. Thomas Disch’s The Prisoner was also very gripping for being a TV spin-off.

Disappointment

Although A Monster Calls was unbelievably good, Patrick Ness’ Chaos Walking trilogy, while clever, did not end well. I felt it got lost in the subversion of its own themes and I ended up not liking any of the characters, who often made unrealistic decisions. The Riddle of the Sands was one that I’ve seen on so many Best Books list but it was almost unbearably tedious for two reasons: 1) The writer is almost obsessed with the word ‘galliot’. 2) Every movement of the boat was detailed, with maps, and 80% of those movements were inconsequential to the plot. The Worm Ouroboros by E R Eddison was another incomprehensible mess. One of the first fantasy epics, there were actually fewer and fewer fantasy elements as the book went on. His imagination only went so far: there were demons, goblins, and vampires — but they were from Demonland, Goblinland, and Vampireland. (It was never said where the genies were from, but three guesses.) The story started with an interesting framing device, but that was never picked up again.

Remembrance

We lost Terry Pratchett this year. I started rereading the Discworld books again. Which was a shame, since last year’s Raising Steam catapulted his world into a new realm. I’m so glad that Shepherd’s Crown, which starred my favourite Discworld character of all time, Tiffany Aching, was such a solid finish. There were a couple falters, and the book doesn’t give any sense of completion to the saga, by any means, but it was a delightful read.

The post Books I Read In 2015 appeared first on Ross Lawhead.

December 21, 2015

The Negative Star Wars Review

(This review contains just about every SPOILER imaginable for Star Wars VII: The Force Awakens)

It’s been thirty years since we’ve visited the Star Wars Universe, and you could convince me that just about anything had happened in that galaxy far, far away in that amount of time — but not that nothing had happened.

The new Star Wars movie did a lot of things right, and there’s very little that was actually put on the screen that I found fault with. But as the movie went on, it was what was not shown, what was alluded to, that I found very unsatisfying.

This is what we find has occurred — or, not occurred. The Rebellion is now the Resistance — what it is that they resist, exactly, we don’t know. Progress, perhaps, because at the end of The Return of the Jedi not only have the Hitler and the Goebbles of the Imperial regime been killed, and the Death Star and Super Star Destroyer destroyed, but in the Special Edition, we see Stormtroopers being body-surfed off of high-rises, leading us to believe that the Imperial Government has completely collapsed, leaving it wide open for the new Alliance leadership to step into its place. But in thirty years, what do we find has been achieved?

Precious little, it turns out. There is no new government. The Han/Luke/Leia triumvirate hasn’t brought the peace to the galaxy which was inferred in ROTJ after all. Nor has the very strong cast of secondary characters: Mon Mothma, Admiral Ackbar, Wedge Antilles, and Lando Calrissian — all of whom also have strong leadership experience. These all have completely dropped off the radar.

The greatest Jedi Master in the galaxy, or conflict avoider?

And the original Big Three? How have they spent three decades? Well, Leia has been touring around with forty or fifty other guys in a kind of cut budget Rebel Alliance, using refurbished X-Wing fighters. She doesn’t have any express aims besides finding her brother, Luke, who apparently tried to set up a Jedi Academy. That didn’t work out so well it seems, one of his pupils went to the Dark Side so he got bummed and went to live on an island. He left his lightsaber in a box in the back of a bar somewhere (when I was a kid I thought that his lightsaber was the coolest thing in the world, but Luke felt differently apparently). He rather coyly left a map for anyone trying to find him, which makes less sense the more you think about it.

Hero of the New Republic, or deadbeat dad?

Leia and Han hooked up together long enough to have a son, but then they split up for some reason. Seeing them on screen together, you get the impression that they were both too cynical and facetious to make anything work. No wonder their son grew up to be so angry and alienated, he’s the only one with any sort of emotional depth in the entire galaxy. Han shares screen-time with both Leia and his son separately, but there are no words of love expressed, just low-level regret undercut by a lot of smirking, so he should have seen what was coming. He abandoned his wife and son to wheel and deal with Chewbacca and he thinks he’s going to make everything better with a grin and a handshake?

Essentially, every character we care about has regressed back to who they were before the original trilogy began. And this is what was disappointing to all of us Star Wars mega-fans, those of us who not only loved the movies, but also the books, comics, and video-games which expanded the stories past the events in The Battle of Endor.

Intergalactic politician, or underachiever?

In those stories, called the Expanded Universe, which started in 1991 with the almost simultaneous publications of Timothy Zahn’s Heir to the Empire and Tom Veitch and Cam Kennedy’s Dark Empire comic series, the cast of Star Wars led fruitful and fulfilling lives. In the thirty years of continuity covered by the novels and comics, Han and Liea had conflicts, but stayed married. Leia is not only Chief of State in the New Republic, she also found time to train as a Jedi knight under her brother. Han and Leia had three children, Jacen, Jaina, and Anakin. Luke also marries and has a son, Ben. He sets up a new academy for Jedi, but instead of just one pupil, he starts with half a dozen, and from those he trains up masters, so after thirty years he is well on his way to filling the universe with Jedi again.

I’m not saying that any of that should have been kept, but there’s no reason to throw it out if there isn’t anything at least as interesting to take its place. Everything in the Expanded Universe is all non-canonical now — instead we are presented with a more boring, less inspiring Universe. The heroes that once inspired us thirty years ago have done nothing else inspiring or worthy of anything more than a footnote. No wonder The Force has been asleep all this time.

The post The Negative Star Wars Review appeared first on Ross Lawhead.

July 6, 2015

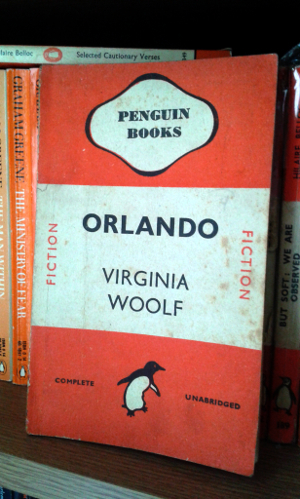

PAW 27 – Orlando (381) by Virginia Woolf

Orlando by Virginia Woolf; Penguin Paperback 381; 1942 edition

What can be said about Orlando that hasn’t already been said, antithesised, argued, counterpointed, reargued, and typed up as a dissertation already?

Not that I would be privy to any of the academic work that has been done on this book, it’s just that I was very aware of the book by reputation, and know how highly many people value Woolf as a thinker and personality… but I just did not get this book.

Again, like reading Zulieka Dobson, I read with a growing suspicion that I was reading a book in that obscure genre of “Magical Realism”. Finding out a little more after finishing it, Woolf wrote it for her close friend (and one-time lover) Vita Sackville-West, as a kind of in-joke about the history of her family. This actually helped reconcile me to Orlando, furnishing an explanation for its purpose. The book starts in the 1600s and concerns the tale of Orlando, a favourite of Queen Elizabeth, who falls in love with a Russian, becomes a foreign diplomat, turns into a woman, meets Alexander Pope, gets tied up in a legal dispute for 150 years regarding her estates, marries a ship captain, stares out the window for another fifty years, and then gets in her car and drives over to Oxford Street to buy some bath salts.

Fair enough. As a plot Orlando is rather unconventional, and though rather absurd (especially when condensed in this fashion), it does give a lot of opportunity to discuss some very meaningful questions. For instance, how is the same person treated differently if they suddenly become a different gender? How do those around them act different? How do they find love? Additionally, how would we consider the passing of the centuries if we experienced them contracted into our lifetime? The main character of Orlando is, in the course of the book, famous and infamous, noble and common, male and female, loved and hated. And what opportunities will Woolf now take to develop the conflicts leading from these contrasts?

Almost none. Orlando, in fact, beset by a complete lack of conflict, most conspicuously absent from the Orlando him/herself. When he is a man he has passions, obsessions, poetry, and love. Once he wakes up a woman, he loses all of that. She (Orlando) is very blaise and doesn’t find it much to write home about, deciding instead to live as a gypsy for a little while. Then she gets kicked out of the tribe and decides to head back home to England. Her old servants are happy to see her again and take her gender transmutation in good humour, and in fact no one really hassles her about it. She is aware of how society limits her participation now she is a woman, but she is not angry about this, at least not to the point where she actually does something. And then the years start to pass and she’s in the late Victorian era, the poem she’s been working on for three hundred years becomes a smash hit but she doesn’t care. She marries a man who she loves completely but doesn’t ever want to be around (which is fine because he’s not), and then the book ends when the story reaches October 11, 1928 (the book’s publication date).

It all just fell very weakly for me. This was frustrating because I went into it really wanting to know what a distinct female perspective was on these different themes — I wanted to know what Woolf thought of gender politics throughout British history, I wanted to know what she thought the differences were between male and female sexual identity, about duty, about love. And I put the book down with almost no further understanding of that.

And yet — look at how I’ve written perhaps the longest review in this series about this short little book. And reading some of the other reviews online, I can see that many people are very passionate about this book, and I would hate to begrudge them their love.

If this book does have a purpose, it is not to explain, but to comfort. It was not written for me to understand something outside of myself, it was written for someone different in order to recognize something particular in themselves.

What is A Penguin a Week? Visit the original site.

The post PAW 27 – Orlando (381) by Virginia Woolf appeared first on Ross Lawhead.

June 29, 2015

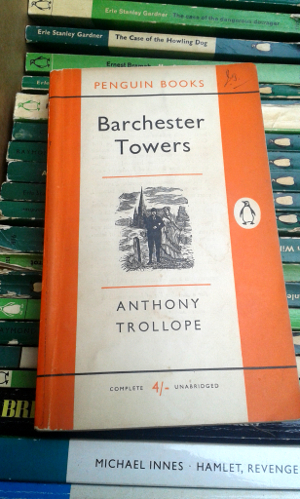

PAW 26 – Barchester Towers (1180) by Anthony Trollope

The Barchester Towers by Anthony Trollope; Penguin Paperback 1180; 1959 edition

Seeing as I my first Penguin A Week post was Trollope’s The Warden, I thought it would be nice to review its sequel, Barchester Towers, at roughly the halfway mark.

As delightful as The Warden was, I found Barchester Towers to be even more so, if only for the reason that it is a longer book, and therefore there is more to delight in. By the standards of most Victorian novels (at least the ones that are still popularly read), The Warden is a novella. Barchester Towers has more of the length and plot development that we would expect when looking at it in context of its contemporaries, such as works by Dickens or Thackery — or even Dumas, Hugo, Tolstoy, etc.

Perversely, I suspect that one of the reasons that Trollope often comes in last when spoken of alongside the authors I just mentioned, is because his work is so much more accessible to the general public, and therefore less appealing to academicians. He is much more relaxed and less abstracted than Dickens and Thackeray. He has a point of view, but he does not seem to care whether the reader shares that or not. He draws attention to himself in the narrative without ostentation, just as someone who is relating a story, informally, after a meal, and who breaks away to explain a point that might hinder understanding or enjoyment later on. Whatever the aims of Victorian Literature may have been, Trollope’s express interest is simply in having you, the reader, enjoy the story, and if it is not enjoyed, then Trollope is obviously happy for you to find amusement elsewhere, and will carry on with his tales with those who are still present for it. (One of my favourite asides occurs in Chapter 6, where Trollope himself, without even using a mouthpiece character, launches into an invective against the modern church sermon

This is a very refreshing aspect for anyone who has read and enjoyed a lot of Victorian fiction. And as with The Warden, the cast of characters is rich and well-developed. Trollope comes close to creating villains in this work in the form of the pious Proudies and the oleaginous Mr Slope. There are also the Stanhopes adding a great deal of conflict into the quiet Barsetshire community with their total indifference towards the problems that they create. Trollope very wittily describes them thus:

The Stanhopes would visit you in your sickness (provided it was not contagious), would bring you oranges, French novels, and the last new bit of scandal, and then hear of your death or recovery with an equally indifferent composure.

The Grantlys and the Hardings in this book, as in the last, stand at the centre, fighting the good fight against modernism, progressivism, and reform. And so it makes the reading of it rather bittersweet, for the England they fought for is now long gone. But the feeling and intelligence of that age is luckily preserved for us in this and the rest of the Barset novels.

What is A Penguin a Week? Visit the original site.

The post PAW 26 – Barchester Towers (1180) by Anthony Trollope appeared first on Ross Lawhead.

June 22, 2015

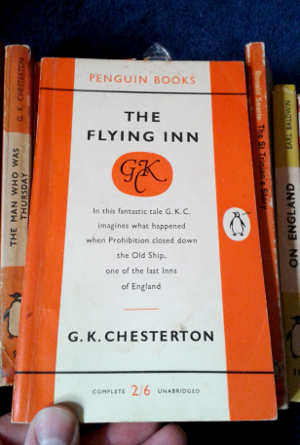

PAW 25 – The Flying Inn (1338) by G. K. Chesterton

The Flying Inn by G. K. Chesterton; Penguin Paperback 1338; 1958 edition

The Flying Inn is one of Chesterton’s non-detective fictions. Running in similar a vein to Manalive, the action is less plot-based than character. There is a distinct situation that is created at the start of the story, which is that in the near future, the UK votes for prohibition and so the entire country becomes dry. The two main characters of the book, Humphrey Pump and Captain Patrick Dalroy, decide to take to the road with a wheel of cheese and a cask of wine, becoming outlaws, intending to set up their ‘flying inn’ by the roadsides.

The plot, like much speculative fiction, was more outlandish at the time than it might seem now. Chesterton preceded the adoption of prohibition in the US by three years. And although the book has a serious point to make about life and humanity — chiefly that you cannot legislate morality, and that austerity is very far away from piety — the book is also very much a comedic romp. Unlike any of Chesterton’s other novels, it incorporates poetry into the narrative, many of which have become very popular like The Rolling English Road, which begins

Before the Roman came to Rye or out to Severn strode,

The rolling English drunkard made the rolling English road.

A reeling road, a rolling road, that rambles round the shire,

And after him the parson ran, the sexton and the squire;

A merry road, a mazy road, and such as we did tread

The night we went to Birmingham by way of Beachy Head.

The poems in this The Flying Inn were so popular they were collected into an entirely different book called Wine, Water, and Song. My personal favourite is The Song of Right and Wrong.

This book also contains one of my favourite chapters ever written, which I have already discussed at length in this blog.

What is A Penguin a Week? Visit the original site.

The post PAW 25 – The Flying Inn (1338) by G. K. Chesterton appeared first on Ross Lawhead.

June 15, 2015

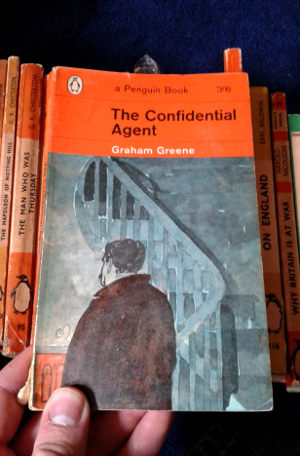

PAW 24 – The Confidential Agent (1895) by Graham Greene

The Confidential Agent by Graham Greene; Penguin Paperback (1895); 1963 edition; cover by Paul Hogarth

The Confidential Agent is an early Graham Greene book, written in 1939 when he was still on the rise. Like The Comforters by Muriel Spark, it was written under the influence of mild psychoactives, in this case Benzedrine. Greene wrote it at the same time that he wrote The Power and The Glory, which he was finding very hard work. After taking a tablet of Benzedrine in the morning, he would write 2,000 words of The Confidential Agent, and then return back to P&G in the afternoon. The book was finished in six weeks.

As such, Greene never really felt it was a book that he actually wrote, and in fact it was one of his own books that he actually reread later on in life. When it was written, he petitioned to have it published under a pseudonym, not so much because he was ashamed, but because he felt it belonged to someone else (although it’s possible he didn’t want to confuse his readership. Throughout his career he was very particular about designating certain books ‘entertainments’, as distinct from his more serious fiction).

All of that said, The Confidential Agent is, through and through, Greene, and could never have been written by anyone else except Greene. The story has to do with a secret, or ‘confidential’, agent who has come to England from the European mainland (although this is never mentioned, it is fairly obviously Spain) in order to buy coal for his country’s revolutionary war effort. As is usual with Greene (who can easily be seen as a precursor to writers like LeCarre), he completely undercuts the genre from any of the drama and set action scenarios that other spy story practitioners would — even in one of his own entertainments, he couldn’t bring himself to create anything less than a three-dimensional, internally flawed and morally ambiguous character.

A wonderfully delightful book, it certainly does not measure short when taking its place among the rest of Greene’s cannon.

What is A Penguin a Week? Visit the original site.

The post PAW 24 – The Confidential Agent (1895) by Graham Greene appeared first on Ross Lawhead.

June 8, 2015

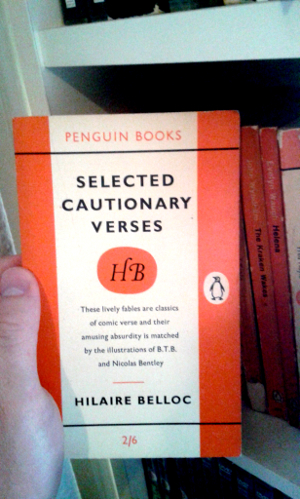

PAW 23 – Selected Cautionary Verses (1349) by Hilaire Belloc

Selected Cautionary Verses by Hillaire Belloc; Penguin Paperback 1349; 1958 edition

Selected Cautionary Verses is a collection of verses pulled from Belloc’s books of humorous poetry, Cautionary Tales for Children, New Cautionary Tales, The Bad Child’s Book of Beasts, More Beasts for Worse Children (my vote for best sequel title of the 20th Century), More Peers, and Ladies and Gentlemen. The book is illustrated by Nicolas Bentley and ‘B. T. B.’, or Basil Temple Blackwood. Bentley was the son of Edmund Clerihew Bentley, a friend of Belloc’s, and G. K. Chesterton. And of particular interest to Penguin Paperback collectors, this is a rare (unique?) work that was first published as a Puffin Story Book (PS67) in 1950 before being reissued as a Penguin in 1958.

The first poem, titled ‘Jim (Who Ran Away From His Nurse, And Was Eaten By A Lion)’ is still fairly well known, and is always a joy to read. The rest of the poems, sadly, do not age well. I think that a lot of the original humour is predicated on the over-moralising of Victorian Children’s poetry, which we simply aren’t familiar with anymore, thank God.

As it stands, it is a satire on something that we don’t recognise and so it cuts a strange shape. The verses themselves are not so accomplished – the line metres are occasionally fudged, to poor effect. Some of them (including the pictures) would now be considered racist. There aren’t a lot of poems in the collection, and sometimes the layout interferes with the flow.

That said, these are intended as light verses, so maybe we shouldn’t give them so much weight.

What is A Penguin a Week? Visit the original site.

The post PAW 23 – Selected Cautionary Verses (1349) by Hilaire Belloc appeared first on Ross Lawhead.

May 31, 2015

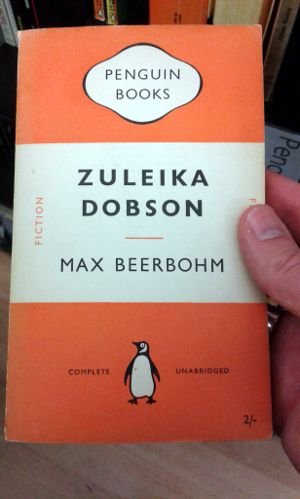

PAW 22 – Zuleika Dobson (895) by Max Beerbohm

Zuleika Dobson by Max Beerbohm; Penguin Paperback 895; 1950 edition

Zuleika Dobson is a book that caught me slightly wrong-footed, and I’m not certain that I ever really recovered through my reading of it. I’m not sure if I could classify this book as ‘magical realism’ since I’ve always avoided that genre, which is not really a genre, but is really just a method of writing which pretends to be imaginative but is only just pretentious and needlessly abstruse. It is written for, and presumably by, people who turn their noses up at SF and Fantasy but still find their souls lacking of it. It is the small beer, the alco-pop of genre fiction.

If I haven’t lost you with that last paragraph, I will say that Zuleika Dobson is undoubtedly clever and well written. But still, that cleverness smacks of pretension and it may just be that I don’t know enough about, or sufficiently appreciate, Classic Greek drama, that I could only pick up small clues and inferences to ancient tragedy that would have made more sense of the whole matter. As it was, the plot, characterizations, and resolution were all lost on me. The only thing that wasn’t lost on me were the descriptions and impressionism of Oxford, which was comfortingly faithful even through the lens of one hundred years.

The plot deals with the beautiful and much-famed Zuleika Dobson arriving at Oxford to visit her rather estranged uncle. She lived as an orphan and found world fame through being a stage magician, which is odd because Beerbohm often stresses that she is not more beautiful than any other character, her act is practically infantile and was stolen from someone who bought it as a kit. And yet all the youths of Oxford are willing to die for her. The other main character, the Duke of Dorset, has more to recommend him as a person, but he allows himself to be wholly commanded by the fates, or non-specific Grecian gods, or Beerbohm himself, and so has very little will or agency in the plot.

There is also a strong misogyny running through the book. The Duke is strong, faithful, stoic, passionate, and is the pattern of manhood which all others judge themselves against. Zuleika is mercurial, mischievous, fickle, proud, and demanding of sacrifice and attention.

Overall impression: amusing in parts, ultimately disappointing.

What is A Penguin a Week? Visit the original site.

The post PAW 22 – Zuleika Dobson (895) by Max Beerbohm appeared first on Ross Lawhead.

May 25, 2015

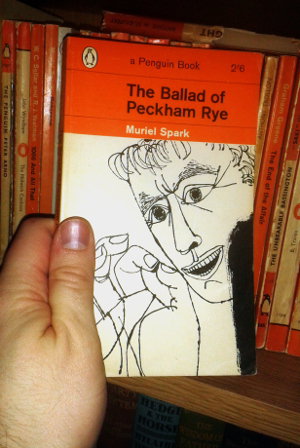

PAW 21 – The Ballad of Peckham Rye (1909) by Muriel Spark

The Ballad of Peckham Rye by Muriel Spark; Penguin Paperback 1909; 1963 edition, illustration by Terrence Greer

The Ballad of Peckham Rye is the third Muriel Spark book that I’ve read in this review series. It’s the only one I was aware of before this list and it’s actually the one I enjoyed the least, although I did admire it.

It mostly follows one character, Dougal Douglas (AKA Douglas Dougal), but it is much less cohesive than many of her other books (at least the ones I’ve read). The central premise is that a successful manufacturer wishes to engage a creative spirit as a consultant to help energize and enliven his work staff who he fears are becoming too dehumanized.

Of course, this is Muriel Spark, so there is a necessary subversion of the central premise, and that is that the creative consultant, Dougal, is malicious, possibly insane, and self-avowedly evil. He brings chaos with him, but it is destructive chaos and not creative chaos. Where another author might show how such an artistic spirit enlivens those around him, bringing joy and self-realization through his impishness, Spark’s tale is much more cautionary than prescriptive. Just because something challenges you and pushes you out of your comfort zone– that doesn’t mean that it’s good and healthy for you. Dougal Douglas is shown to take advantage of his position, slows productivity in the factory, and moonlights for another company, all under the banner of liberalism.

As such, it’s hard to tell exactly where Spark’s sympathies lie, or what he opinion might be. But of course Spark is far too sophisticated an author to betray this, which is not intended as a slight. As is typical with her, and Grahame Greene (who I keep drawing comparisons with–favorably, I hope), the method is simply just to present human nature, in its ugliness and brokenness and beauty, and then let the reader draw inferences and conclusions for themselves.

What is A Penguin a Week? Visit the original site.

The post PAW 21 – The Ballad of Peckham Rye (1909) by Muriel Spark appeared first on Ross Lawhead.

May 18, 2015

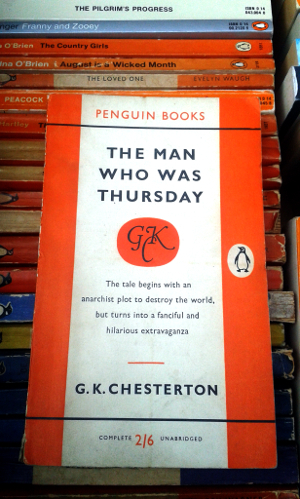

PAW 20 – The Man Who Was Thursday (95) by G K Chesterton

The Man Who Was Thursday by G K Chesterton; Penguin Paperback 95; 1954 edition

The Man Who Was Thursday is a metaphysical mystery/thriller. There aren’t many of this ilk written anymore. It’s one of Chesterton’s most accessible novels, and it’s been great to see that it’s achieved a sort of resurgence in recent years — there are many modern editions of it currently in print. The late, great Terry Pratchett sings its praises frequently, and Neil Gaiman is an avowed fan of GKC.

The Man Who Was Thursday is a sort of long parable, although Chesterton describes it as “a nightmare”. In subject matter it’s closer to the fiction works of Charles Williams than anything else, but it is cast in a spy-thriller format, making it compulsively readable. The main character, Gabriel Syme, begins in a setting that Ian Fleming might conceive, but quickly gets drawn in to a looking-glass world of inverted beliefs and alliances.

As with my other favourite Chesterton novel, The Ball and the Cross, it is a mistake to assume (as Adam Gopernik did in a New Yorker review of Chesterton) that Syme, as the main character, is always and truly in the right as he fights a world of wrong. What I find most delightful about this story is the very subtle and gradual changes that his character makes after each and every triumph, so that at the end of the book he is a very different character, with a very different outlook, and you haven’t been aware that he has gone through any change at all–but he has, and so have we.

The Man Who Was Thursday is a book I keep reading by accident. Since 2001 I have done so six times. I’ll start by looking back through it for a favourite line, then I’ll read a few more pages, and then finish the chapter, and then go back to the begin and start in earnest. It’s one of the most perfect novels I’ve read, and it won’t be many years before I’ve read it another half dozen times.

What is A Penguin a Week? Visit the original site.

The post PAW 20 – The Man Who Was Thursday (95) by G K Chesterton appeared first on Ross Lawhead.

Ross Lawhead's Blog

- Ross Lawhead's profile

- 31 followers