Ross Lawhead's Blog, page 8

January 11, 2015

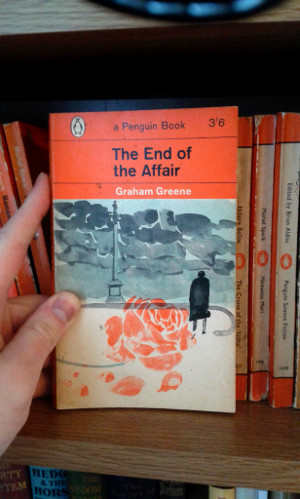

PAW 2 – The End of the Affair (1785) by Graham Greene

The End of the Affair by Graham Greene; Penguin Paperback (1785); 1962 edition; cover by Paul Hogarth

The End of the Affair is a unique fusion of genres… a religious mystery romance thriller. Greene was already renowned at the time for writing in all of those genres, but this is a particularly heady distillation. As a “way in” to Greene, I heartily recommend this book.

The plot is laid out in what would easily translate into a classic film noir storyline — a man is investigating a sudden change of mood in his adulterous lover. Shades of The Third Man already. But in the course of his investigation, he is brought face-to-ineffable-face with God and His love and grace. It should be trite and twee, and in anyone’s hands but Greene’s it would be. He writes with the perfect amount of cynicism and superciliousness to stop the story from turning into a Sunday school lesson once it concludes. The narrator is agnostic, and Greene is such an intelligent Catholic mind that comfortable holds the conflicts and paradoxes of life neatly in perfect tension.

Graham Greene was the author that first brought me to the classic Penguin Paperbacks. A very good friend of mine once gave me a stack of his books in the orange spine editions for Christmas a few years back. Due to an early run-in with Greene in High School in which I completely undervalued and misunderstood his short story ‘The Destructors’, I avoided Greene, dismissing him as an embittered and angry soul. But growing up and learning to doubt religion and life, I found a compatriot and mentor in Greene who was able to doubt even more audaciously than I was, showing a brokenness to humanity that indicated larger universal truths. My Penguin Classics Graham Greene collection is now vast, fueled also by my love for his decades-long dedicated cover artist Paul Hogarth.

What is A Penguin a Week? Visit the original site.

The post PAW 2 – The End of the Affair (1785) by Graham Greene appeared first on Ross Lawhead.

January 4, 2015

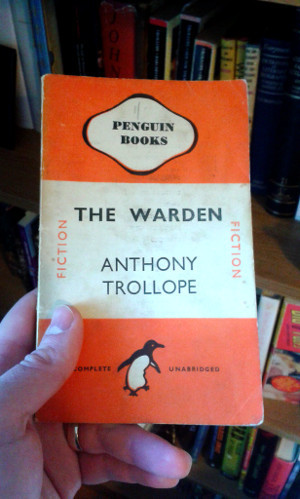

PAW 1 – The Warden (495) by Anthony Trollope

The Warden by Anthony Trollope; Penguin Paperback (495); 1945 edition

The Warden was a surprise for me. I had heard of Trollope but never read one of his novels. He always seemed to place below Dickens, Thackeray, Eliot, Austen, and others in the cannon of Victorian literature. And even though I am a huge fan of the very excellent The Way We Live Now TV adaptation, I wasn’t expecting much. But at 175 pages, I thought I’d give this one a try, and I was blown away by how good it was.

For a start, the style is much more readable than Dickens or Austen. It was very relaxed and concerned more with telling the actual story than in impressing the reader with experimentalism or exposition. It made me wonder why he isn’t read more these days since there were very rarely any dense passages. The plot itself was magnificently crafted. Victorian literature was, as stories of today are, very fond of “The Villain”. In The Warden there is no true villain — every character believes that he or she is doing right, and the true genius of Trollope is that he convinces you, the reader, that each character is right as well. The conflict is born from the hearts of characters who are not acting maliciously (or even impolitely) to each other, but are dead set against one another out of duty and honour.

The set up is brilliant. Mr Harding is an elderly widower with a small but comfortable position in the church where he looks after some few men and women who have been retired due to injury. He draws a stipend for doing this very small and easy act of charity, as well as the use of a nice property. The young reformer John Bold believes that the money and property are not being used to particularly good effect and starts to pursue means of removing both position and property from Mr Harding. And then he falls in love with Mr Harding’s daughter, Eleanor, just as his plan to ruin her father gains too much steam to stop…

That is the core of the book, the three characters caught up in nets of their own desires, duties, and affections. However, every other character proliferating from those three — Harding’s other daughter, her husband the Archdeacon Grantly, Eleanor’s friend and John’s sister Mary Bold, and even the newspaperman Tom Towers — all have fully thought through motives and unique philosophies. It made me think a lot more of Mr Trollope whose worldview must have been immense in order to encapsulate so many others. I’m really looking forward to reading the other books in the Chronicles of Barsetshire.

What is A Penguin a Week? Visit the original site.

The post PAW 1 – The Warden (495) by Anthony Trollope appeared first on Ross Lawhead.

PAW – Penguin A Week (Preamble)

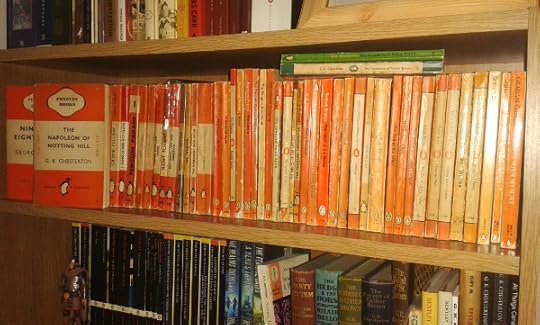

“Shelf A”

For a few years now I’ve really enjoyed the A Penguin A Week blog written by Karyn Reeves. In it, she has set herself the task of reading one of the pre-ISBN Penguin paperback books (of which there are 3,000) each week, and then writing a short review about them. It has really helped me investigate and enjoy this original line of influential books, many of which are classics and just as many of which are mostly forgotten, and helped broaden and even challenge my reading tastes.

And so, as a kind of tribute, but also as a way of sharing and perhaps inspiring a passion, I’m going to be blogging 52 Penguin books this year as well (without the knowledge or approval of Ms Reeves, whose site I heartily recommend that you visit, as well as one of the sister sites which is all about the cover artists).

The post PAW – Penguin A Week (Preamble) appeared first on Ross Lawhead.

January 1, 2015

Books I read 2014

Here is a list of (nearly) all the books I read in 2014*. Perennial favourites continue to be Muriel Spark and Graham Greene. I’m having great fun going through Anthony Trollope’s Barchester Chronicles — Framely Parsonage was another enjoyable chapter in that work — and I’ve almost rounded off my sequential read-through of James Bond. You Only Live Twice astounded me in how far the author took his creation, whereas The Man With The Golden Gun proved to be nothing more than a padded novella which unsettled the satisfying end of its predecessor. Tehanu was as good as any fantasy book could hope to get, and the same could be said of Children of Dune, which is definitely more Fantasy than SF. I’ve started revisiting past favourites as well and while A Little Princess completely lived up to the joy I found on its first reading, American Gods by Neil Gaiman did not. I read the extended version of AG this time around, and I think that the swiftness of the punch was lost in the extra material that was added; it still rightly deserves the acclaim it has received, however.

*Exempted are the books I read as research for my writing.

The Shadow Lamp, Stephen Lawhead

Doctor Who: Ten Little Aliens, Stephen Cole

Thunderball, Ian Fleming

On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, Ian Fleming

Robinson, Muriel Spark

May We Borrow Your Husband? Graham Greene

Clothe Your Family in Corduroy and Denim, David Sedaris

The Unbearable Bassington, Saki

You Only Live Twice, Ian Fleming

Star Wars: Dawn of the Jedi: Into the Void, Tim Lebbon

Children of Dune, Frank Herbert

A Little Princess, Frances Hodgson Burnett

The Man With The Golden Gun, Ian Fleming

The Blue Fairy Book, Andrew Lang

We, Yevgeny Zamyatin

Common Sense, Thomas Paine

The Thirteen Clocks, James Thuber

The Girl Who Circumnavigated Fairyland in a Ship of Her Own Making, Catherynne Valente

Tehanu, Ursula K Leguin

Who Goes There? John W. Campbell jr

The Odyssey: A Retelling, Simon Armitage

Let’s Explore Diabetes With Owls, David Sedaris

Framley Parsonage, Anthony Trollope

How to Speak Money, John Lanchester

Travels With My Aunt, Graham Greene

The House at Pooh Corner, A. A. Milne

American Gods (Author’s Own Edition), Neil Gaiman

The post Books I read 2014 appeared first on Ross Lawhead.

December 29, 2014

The Logic

A part of the current Christian culture is having a “testimony”; and for want of a better term, this is mine. Often peoples’ testimonies follow a standard progression of rebelliousness, living for the self, finding the hollowness and destruction that follows that, and having a spiritual experience with God either directly, through the spirit, or through the Bible, or through the love of another Christian. These elements: love, grace, and forgiveness, are fundamental to life in Christ, but less common in conversion stories are the three elements of my conversion story: logic, reason, and doubt. And especially doubt. There’s no right, or “better” way to come to Christ, but this was mine.

In short, it was actually the arguments against Christianity that most drove me to it. It was being at school and learning about the material world, learning to reason through logically about the world around me, and doubting what was told to me in class just as much as I doubted what I was taught in Sunday school.

The thing about the materialist point of view, and by that I mean the people who preach that you can only believe in what you can see and quantify, is that the things that you can’t see or quantify are so massively important. You only have to step a short ways into the scientific community, say, to see the two faces of it. On the outside is this adamant front that says that all answers are within, science explains everything. But pick up any popular science magazine and you’ll see all the glee and exuberance at what is still unknown and left to find out in the “scientific world”: gravity, dark matter, anti-matter, just plain regular matter. And there are wonderful theories: Theories of Everything, String-Theories, Grand Unified Theories, and then the apparently anything-goes mirrorland of Quantum Electro-Dynamics. I found all of that exciting and thrilling, and yet there is this scientific hypocrisy persisted: science answers all questions/isn’t it wonderful how many questions we still have?

What materialist and theologist both agree on completely is that we are both here, and that there is a “here” to be on. There is a created world, and it was created by a creative force. Something is here and so something made it, and for myself (and many Christians) I see no reason why we can’t call that something God. Materialists suddenly balk at that, because God implies a consciousness, but I don’t see why that should immediately be taken off the table. There certainly is a mental world, a conscious world, why should that not have been created also, and have a point of origin? And why would that also not be a part of the original creative force that made everything? And then there are the abstracts which, unlike the mental world, leave no physical trace: love, hate, ambition, kindness, lust, what we could call the moral world — why would these not also be aspects of the original creative force, especially when you can plainly divide those moral aspects into creative (or generative) and destructive (degenerative)? And as all these elements of material, psyche, and spirit met together in each person, why would they not also meet in that original creative force?

So why not call this first creative, mental, and moral force God? The scientists and materialists said the universe was bigger than we could imagine and I agreed. I went further, in fact, in believing that it is even bigger than they imagine, since they are determined to still put limits on it and deny that there is an emotional or moral aspect to it (or at least that those aspects have meaning*).

And if there was such a three-in-one entity (which also encompassed all that we still have yet to find out about the universe, see par. 3), would it not want to reach out and make itself known to us, in those three (or more) aspects? And if it did, at some point in human history, would it not look almost exactly as was reported in the four eyewitness accounts of the gospels?

Everyone will have to follow their own logic and heart in that, but I answered yes. And of course, once I did, and once I had created this new logical framework to what I believed, I found that people had been inventing exactly the same framework, very calmly and routinely for millennia. Literally for thousands of years people have been reasoning themselves into the Christian church. Thomas Aquinas is one whom I am fond of, one of the first of the rigorous logicians. So to, C. S. Lewis, although he always seemed rather condescending, in the natural way of an Oxford don. But G. K. Chesterton was the most profound reasoner, for me. Here was someone who had already followed the same paths that I had, but quicker, easier, and with more awareness and clarity than I had the capacity. His Introduction to Job, for instance, already says what I am trying to say here with almost effortless efficiency:

In dealing with the arrogant asserter of doubt, it is not the right method to tell him to stop doubting. It is rather the right method to tell him to go on doubting , to doubt a little more, to doubt every day newer and wilder things in the universe, until at last, by some strange enlightenment, he may begin to doubt himself.

And the conclusion of Job itself is summed up “The riddles of God are more satisfying than the solutions of man,” which is exactly what I have found to be the case.

And of course, the Bible itself was consistently uncompromising in saying that God is not something that can ever be explained, reduced, or limited, even though He can be known — in fact there is little point to anything else if you do not know Him, which is only to say that there is no point in living in this world if you do not fully engage in all aspects of it, to love, live, and feed not on yourself, but on the things that are greater than yourself, the mysteries of the seen and unseen universe.

So I had no choice to be a believer. In fact, none of us have a choice in what we believe — but some people prefer the lie to the reality. But in doubting and testing the truths that I was told from every quarter, I found that the Truth always stood standing when I had finished, and that everything that fell away was meaningless obfuscation, the effect of which was to make my world smaller.

What I was forced to believe was this: that there is a God, that He loves us, and that He sent His son Jesus Christ in order that we might be closer to Him. And understanding that truth is freedom.

*Richard Dawkin’s book The God Delusion was a small revelation in itself. A man who claims complete rationality in all of his beliefs has presented us with a book full of subjective, emotional speculation. For a cold rationalist who claims to put reason above emotion, he sure does seem to hate a lot.

The post The Logic appeared first on Ross Lawhead.

December 24, 2014

The Christmas Tree House

The old woman down the hall from us tells this story of the Christmas Tree House:

One year I spent Christmas in a tree. I was with my sister who was a year older than I was, and I was eight. At that time it was only her and me and father, who was very sick. Very sick. We thought he might die, and so did the doctors. He was so sick that they wouldn’t let him out of hospital. At that time I didn’t know what was happening, I just knew he wouldn’t wake up. I remember we visited him in hospital and he was so weak he couldn’t even open his eyes.

So instead of going to a council run home, the two of us decided to live in a tree. I don’t know whose idea it was, but we both loved it. This was the large tree that used to stand every year in the middle of the town square, which isn’t there anymore. It was a gift from the King of Lapland, sent every December as thanks to the men in our village for liberating one of the larger towns in that country during World War II.

My sister and I climbed into that tree and didn’t climb back down again for two more weeks. And we found that if we climbed almost to the top, we could look across to father’s room in the hospital, on the second floor, it was that big.

It’s not as cold in a pine tree than you might imagine, or it not in that one at least. The bristles on the branches were so thick that the strongest wind would come through only as a pleasant breeze. That rich, beautiful pine smell was constant. In the day the light would filter through in little splinters, and at night we had the Christmas lights, of course. You could only get white ones in those days, so it was like being in a galaxy. I would sit on one of the branches and look around me and pretend I was my own planet in space.

We had our own rooms. These were the large, gift-wrapped wooden boxes that were placed under the tree as props. We found they were hollow at the bottom, so we carried those into the branches and secured them with bits of tinsel that we plucked from the decorations. I had a green box and Mary had a blue one. There was a small silver box that we put our food and school books in.

Yes, we did manage to find food. Even two little girls can’t be kept secret in a tree in the middle of town. I don’t know who found us out first, but the first either of us knew was that on the second day two policewomen were pushing their way through the bottom branches, along with a journalist for the local paper. I can’t remember what they said, they were shouting up and Mary was shouting down. Of course they wanted us out of the tree, and I was about to gather my things when a fourth woman pushed through the lower branches and stopped the policewomen. She explained that technically the tree was not in the England, it was resting in Lapland soil, and so it was a part of that sovereign nation. Any act of aggression could be considered a hostile movement on the Kingdom of Lapland.

But I was getting to the food: once the paper came out in the afternoon, with the article about us, our father, and the whole situation explained, everyone in town wanted to come and the two little girls living in the Christmas Tree House. And some of them gave us gifts, like blankets which we padded our rooms with, hats and scarves, food for us to eat, like fruit and pies, mugs of steaming hot chocolate, and also money.

Now the money we felt guilty about. The food and the clothing we were used to getting free — we were children, after all — but not so the money. We knew how hard our father worked for his money, and here we hadn’t done anything. We felt we should give something back, and so we struck on the idea of singing Christmas carols. I can imagine that we were very good singers, but we certainly were enthusiastic. We would sit in the upper branches where we could see out easier and just belt out one carol after another. Then the money really started coming in. The coins fell to the ground and were easy to gather, but the notes were more difficult, often we had to balance very precariously in order to pluck them from the branches. In all, we made almost fifty pounds in a week, and that was a lot of money back then — a fortune to us. We kept it all in the silver box.

The BBC even did a report on us, on the Friday. The truck drove out and unloaded a film camera — it had to be film in those days if it was outdoors. They talked to some of the people in the square, also the councilwoman who told the policewomen they couldn’t remove us, and then shot some footage of my sister and I climbing through the tree and singing our Christmas carols. They ran it that Saturday, although it wasn’t years later that I actually saw the report itself.

One day it snowed heavily overnight. Mary and I woke up and it was dark all around us. It was so thick on the ground that cars and lorries couldn’t use the streets and so everything was perfectly still and quiet. Every once in a while we would hear people crossing the square and we could hear every word they said perfectly. Then some children came out and we could hear them fight and play, every whistle and every snowball that hit. No one came to see us and we didn’t sing, we just ate cold pies, drank melted snow, and Mary read to men from her books as we sat bundled in our boxes. That was my favourite day.

Then it was the morning on Christmas Eve and a whole bunch of people started to congregate around the tree. We didn’t know why. Our voices were tired from singing so we had given that up. We noticed a lot of policemen and we thought that they would come in to drag us out, but then three cars arrived, very handsome, sleek cars. And a little round man in a big hat and coat got out and came to the tree. He took a piece of folded paper out of his pocket and read it to us — it was from the King of Lapland. He gave us a very formal greeting, thanked us for visiting his land, made some sympathetic remarks about our father, and then extended to us the hospitality of his land whenever we cared to visit it. And then the man folded the letter, put it back in his pocket, and extended his arms, saying that his name was Hánno, he was the appointed Ambassador of Lapland, and that his home in the Embassy was available for us to stay at for as long as we might need it, for as long as our father was in the hospital.

By this time Mary and I had forgotten what it felt like to be truly warm all over, and we were sore from sitting and climbing on branches all day, so we came down and out of the tree, to the applause of the people gathered. We went straight into the car with the Ambassador of Lapland and drove all the way to London — further than I had ever been — to spend Christmas and New Years with him and his family. His children were older than we were, but they played games with us anyway. It took me six days to get all the tree sap out of my hair. We stayed with him until our father was better and then we were driven back. The money we made singing helped us get on our feet after that.

Every year, for as long as Hánno was ambassador, we visited him in the Embassy inLondon for dinner at Christmas Eve. I cherish memories of the times we had with him and his family even dearer than that of our time in the tree. I even learnt a little of the Lapland language although most of it I don’t remember now.

But I do remember the first phrase I learnt: “Buorrit Juovllat,” and that means Merry Christmas.

The post The Christmas Tree House appeared first on Ross Lawhead.

July 6, 2014

The Spirit of the Bard

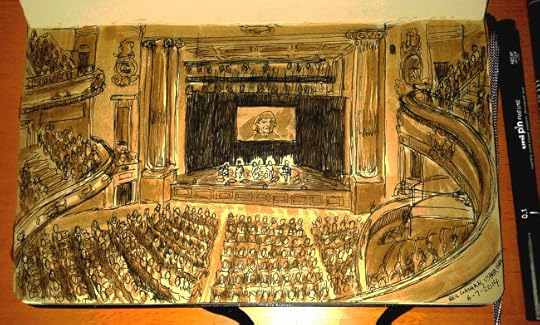

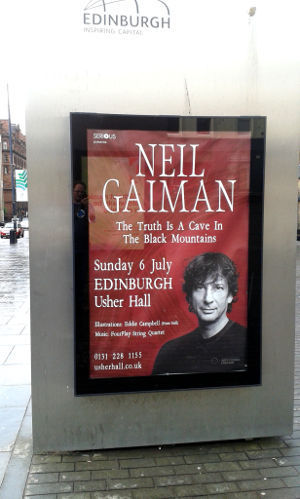

Neil Gaiman and Four Play at Usher Hall, Edinburgh. They said “no cameras”…. but not “no sketchbooks”. Illustration by the author (this author).

Tonight I was fortunate enough to go to a performance by Neil Gaiman who was reading his latest book, The Truth is a Cave in the Black Mountains. It was held in Edinburgh’s wonderful Usher Hall, and from what I could tell, it was completely sold out. I’ve been thinking a lot about the state of the publishing industry lately (as every author has been) and the show tonight brought home to me something that I’ve been noticing in all of the chatter, and that is that there are many writing fashions that are quickly falling — but not as quickly as the ones that are rising — but also that the pure and eternal element of story is still intact and as vital as ever; vital in the sense that it is alive, aware, and powerful.

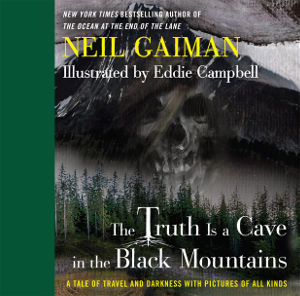

Mr Gaiman shared his stage with a very excellent Australian string quartet called FourPlay, who were able to make four instruments sound like sixteen. With the artwork of Eddie Campbell projected on a screen, FourPlay and were endlessly inventive in creating background moods, sounds, tones, and melodies to accompany the main reading, although they also performed their own work, and on two occasions backed Mr Gaiman as he sung — something I personally was not aware that he did, and I was impressed that he did it well. There were two short stories read, as well as the advertised novella which is a wonderful shell game of morality, thwarting the reader’s (listener’s) predictions as to exactly what kind of moral tale it is.

Mr Gaiman shared his stage with a very excellent Australian string quartet called FourPlay, who were able to make four instruments sound like sixteen. With the artwork of Eddie Campbell projected on a screen, FourPlay and were endlessly inventive in creating background moods, sounds, tones, and melodies to accompany the main reading, although they also performed their own work, and on two occasions backed Mr Gaiman as he sung — something I personally was not aware that he did, and I was impressed that he did it well. There were two short stories read, as well as the advertised novella which is a wonderful shell game of morality, thwarting the reader’s (listener’s) predictions as to exactly what kind of moral tale it is.

It was a wonderful evening, and all of it raised mixed emotions in me. On a very selfish level, I was wondering if this is what it took now for authors to hack it in the industry. Was it not enough to only write a book, but were we all now required to go on the road and find new ways to promote it? To bring it to our audiences in person? And not only that, but to now be expected to sing?

If you’ve ever got to know an author personally, you know what a big ask that is. It isn’t that authors aren’t entertaining — we can very easily be the life of the party. It’s just that we are so rarely at parties. The reason that we become writers is because we enjoy being by ourselves just about all of the time. We hide, we close the door in secret. We work at night, we don’t have many friends because we just don’t have the time to invest in them. Sometimes we even change our names so it’s harder to find us. We’re the ones that sit at the back and watch. We shake your hand but do not look you in the eye. We make notes, go away to our rooms or garrets or sheds, and then a week or two later slide some pages under the door and ask for a cup of tea.

That’s what the life of the novelist has looked like for the last hundred years. Yes, there have been exceptions. There have been unabashedly shameless self-promoters, but there are also just as many authors who are so obscure, it’s possible that not even their editors knew who they were. Remind me to tell you about B. Traven some time, and is there anyone for a round of Who Wrote Shakespeare? Yet, tragically, it is not overstating the matter to say that the modern novelist, as we know it, is exiting our realm, just like the ghostly procession of Elves in The Fellowship of the Ring. We are going into the West, not to be seen again. The financial system will no longer support us. The advance for first time writers is below the poverty line. If we were being beaten out of every civilised country with clubs, that would not be more effective. Yes, the professional writer is going — your curse is to be left only with the amateur writers.

The Truth is a Cave in the Black Mountains, 2014, Hardback Cover

That said, if we take an even wider perspective, if we back up so we can see a few more thousand years at a glance, we can see that the professional novelist is something of an irregularity. Throughout history there has been a constant mode of delivering story, and that is through a dedicated individual who would travel from village to village, town to town, hall to hall, and perform long ballads, short poems, usually to his own musical accompaniment. These people were called bards, or skalds, or seanchaidhthe, or rhapsodes, or any other number of formal and respected titles. They would perform existing works, or they would perform their own material. Never were they not expected to do so. All of the greats performed their own material Homer, Taliesin, King David, Shakespeare, Dickens… it was unquestioned, it was a part of the drive of storytelling itself — to tell stories to a live and immediate audience. By a quirk of technology, it has been cost effective for storytelling to be abstracted, and perhaps it’s best that that is no longer the case. Just as musicians are having to turn back to playing before live audiences for their bread, it is perhaps now the time for writers to likewise step up and join the ranks of our artistic ancestors. We should not think of readers anymore, we should think of listeners.

And the performance tonight was a playbook of how to operate such a model. It was, by turns, comforting, provoking, tear-jerking, disturbing, thrilling, and humorous. And it was so successful because Gaiman (et al,) has a foundational understanding of what storytelling is, which he showed by the short story he read The Man Who Forgot Ray Bradbury. It is something that is extremely easy to forget when you are sitting on your own in a room with a stack of paper. Storytelling is not about the teller, it is not about the caftsman, or even the craft. It is about the listener, and the use that the listener can put the stories to, to help, to heal, to warn, or to delight.

June 22, 2014

James Bond’s Happily Ever After

Hardcover 1st Edition

(Warning – contains spoilers relating to the Ian Fleming James Bond novels. It is written to inspire those who have no intention of reading the novels to do so, and to remind those who have done so what was so amazing about the experience.)

A few years ago my friend and co-writer Russell Thompson and I bought boxed sets of the complete James Bond stories and started reading them together. I was struck — as everyone is who reads the books– by how much deeper Bond was portrayed in the books as opposed to the movies. In the movies Bond is a superhero, and no matter what happens to him in any one movie, by the beginning of the next, generally speaking, he is reset to his start position, ready for the next adventure.

But in the books, Bond is human. He still has the same adventures, but Fleming as a writer still seems to maintain a lagging concept of him as a man with finite strengths and abilities. He has a breaking point, and it is almost awe-inspiring to read through twelve novels and find that he is at the complete end of his physical and mental capacity. He is a broken man.

Really, the first crack appeared in the first book, Casino Royale. James Bond’s profound loss of Vesper Lynd was too emotionally intense even for the 2006 revisit/reboot massively underplayed it, distracting the viewer with a largely meaningless action sequence. Thus the teeth were completely taken out of the last line of the novel, one of the most shocking last lines in the history of literature. “The bitch is dead.” Claiming itself to be more faithful to the book, the filmmakers were comparatively at ease — possibly even gleeful in — portraying the torture scenes. But Bond in about to commit to a monogamous relationship evidently made them uncomfortable but this is the first important fixed point of Bond’s emotional character arc.

Penguin Paperback (2006)

“Arc” is a technical writing term and it means that the character’s development starts off in one direction, is acted on by outside forces which affect its change, until it eventually lands somewhere new. And that is exactly what happens with Bond, by degrees, over twelve novels. The movies make so much of James Bond’s serial womanizing, which treats it as a sort of reward for completing his mission — usually blowing up something dangerous. In the books it’s shown — whether consciously by Fleming or not — as a symptom of Bond’s greater tragedy: that every woman that Bond gets close to gets killed. Vesper Lynd was the first — she and Bond were set to get married before she betrayed him and was killed. It took Bond, understandably, roughly nine novels to get over that loss and when he eventually did get married, in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, his arch-nemesis Ernst Stavro Blofeld and companion Irma Bunt kill her as they are driving away from the church. That is how ends, with yet another devastating line delivered by Bond: “It’s quite all right. She’s having a rest. We’ll be going on soon. There’s no hurry, you see — you see, we’ve got all the time in the world.”

But just the act of working and killing for the Secret Service has taken its toll on Bond over almost a dozen missions and OHMSS starts with Bond drafting his resignation letter which he never hands in. By the time the penultimate novel, You Only Live Twice, begins, Bond is emotionally and physically on his metaphorical knees. Picking up some months after his wedding. Bond is still working for the secret service, but he has completely lost his edge, and it is suggested that he has bungled his last few assignments. Bond himself is dissatisfied and self-aware enough to know he has completely lost his taste for the hunt and is brought into M’s office, completely expecting to be put out to pasture. However, he is being sent on one last mission to try to shake him out of his funk.

The bulk of the story is concerned, rather monotonously, with recounting Bond trying to grasp Japanese culture, with mixed success. At the time it was written, in 1964, there had not been an awareness of Japanese culture that the 70s and 80s brought in terms of film, television, anime, and manga. In the 60s it was worth explaining what kung-fu, ninjas, haikus, sushi, etc., were on the assumption that a literary audience was not familiar with it, but by today’s standards the prose is needlessly pedantic and for a good hundred pages there is very little in the way of plot.

The movie (and its poster) decided to go in a different direction than the deep emotion portrayed in the book.

When the plot does kick in again, it is almost exactly the opposite of what a James Bond Movie viewer has been conditioned to expect — more along the lines of a Jason Bourne movie in fact. When Bond finds out that Blofeld and Irma Bund are in the fortress that it is his duty to keep an eye on, he basically suffers a mental break. His break-in to the fortress and subsequent tracking down of Blofeld are anything but heroic. And in the course of this it is revealed that Blofeld himself has been brought to his knees by Bond’s actions in the last two books. Bond’s arch-nemesis, in glorious character counterpoint, has just about as few material and psychical resources as Bond has. The final fight to the death is visceral, inelegant, and dirty. Blofeld has taken everything from Bond and, in a way, Bond has to give the rest of himself to Blofeld in order to destroy him.

When Bond is fished out of the ocean by the formidable woman he has been embedded with — a past movie star and oyster diver — he has completely lost his memory. He does not know his name, his job, his past adventures… nothing that has happened to him in the last eleven books. Even the British Secret Service believes him dead and in fact we have just read his obituary, written by his commander, M, and his secretary, Mary Goodnight. Kissy Suzuki, Bond’s rescuer, does not tell him any of the details of his old life. Instead she tells him that they are lovers and that he lives on the island with her. The months proceed and Bond continues to remember nothing of his past life and Kissy is shown to be completely instrumental in keeping all information from him.

It could seem like a cheat to so transform Bond like this for his last adventure. To completely erase all of the events of the past very popular novels from Bond’s mind. But you are made to realise what exactly is being given Bond here — all of the hurt, the torture, and the mental anguish are being erased from Bond’s mind. His past lovers who have been killed are forgotten and it brings him peace. The physical exertions and bodily punishments which have left him a nervous wreck at the start of this book have likewise melted away. Even the spiritual effects that Bond, at times, is shown to experience, the toll of murdering for the State, and the moral incertitude which that brings, has been wiped clear. Bond also forgets how to have sex and Kissy go to the length of buying a sex manual and leaving it out for him to find. The serial womanizer has even forgotten the hollow and temporary pleasure he found in meaningless physicality. It has to be one of the greatest acts of healing by an author to main character in literary history. Only two others spring to my mind and that is Raskolnikov at the end of Crime and Punishment by Fyodor Dostoevsky, and Arthur Dent in So Long, And Thanks For All the Fish by Douglas Adams. At the end of the book, Bond is made whole and Bond is made happy. It is a beautiful and complete ending to the Bond saga.

It could seem like a cheat to so transform Bond like this for his last adventure. To completely erase all of the events of the past very popular novels from Bond’s mind. But you are made to realise what exactly is being given Bond here — all of the hurt, the torture, and the mental anguish are being erased from Bond’s mind. His past lovers who have been killed are forgotten and it brings him peace. The physical exertions and bodily punishments which have left him a nervous wreck at the start of this book have likewise melted away. Even the spiritual effects that Bond, at times, is shown to experience, the toll of murdering for the State, and the moral incertitude which that brings, has been wiped clear. Bond also forgets how to have sex and Kissy go to the length of buying a sex manual and leaving it out for him to find. The serial womanizer has even forgotten the hollow and temporary pleasure he found in meaningless physicality. It has to be one of the greatest acts of healing by an author to main character in literary history. Only two others spring to my mind and that is Raskolnikov at the end of Crime and Punishment by Fyodor Dostoevsky, and Arthur Dent in So Long, And Thanks For All the Fish by Douglas Adams. At the end of the book, Bond is made whole and Bond is made happy. It is a beautiful and complete ending to the Bond saga.

…that having been said… it is not the end. There is a last page which opens the door for the next and final novel-length Bond adventure, The Man With The Golden Gun, which is a far less satisfying ending and which some argue is not a true Bond book at all, and the short-story collection Octopussy. I prefer to remember You Only Live Twice as the true ending, or the completion, of James Bond, the title of which is taken from a poem that Bond writes in the course of the story:

You only live twice:

Once when you are born

And once when you look death in the face.

Bond, after looking death in the face for the final time, has been absolved by his creator, and is born again.

May 5, 2014

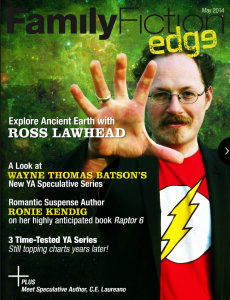

Family Fiction Interview

Below you can read the extended interview that the very kind people at FamilyFiction conducted with me. Ordinarily I wouldn’t have posted this, but I found the questions very thought provoking. To see the resulting article as it appeared in the magazine, you may click on the images underneath, or visit their website.

The burning question on everyone’s mind: Who is the man behind the cartoon avatar?

Me! Or as near to me as I can make it.

Can you give us a brief intro to your Ancient Earth series?

Gladly. The main premise is, in many ways, a standard pre-teen fantasy quest, but something goes wrong, and that is that the children win! The question I ask is “what if winning made everything much, much more unbelievably worse?” The natural follow-up to that question was: “How could they fix that? And how long would that take?” I’m very interested in the moral elements of story, and have been noticing that resolution in the stories being written today, even for Young Adult fiction, is often a violent resolution. I believe this is a contrivance because in the real world violence never fixes problems, it only causes more of them. I wanted to put those real-life consequences into a fantasy story and see what happened then.

Where does The Fearful Gates pick up this tale ?

The last day of the story, literally from sunrise to sunrise. The time frame of the series was unexpected, almost poetic. The first book takes place over an eight year span, the second book is roughly nine days, start to finish, the last book is almost exactly twenty-four hours.

Where did your initial inspiration for the series come from?

From some really unexpected places. I had an idea of what I thought was the perfect fantasy adventure for teens – I had the heroes, the villains, the setting, and even the last scene – but I couldn’t find a way to tie them all together. It was my dad who suggested the idea of using the legend of the sleeping knights which is prevalent not just in the United Kingdom, but also all over Europe. I looked into those stories and things started to click – I was able to make a lot of connections to elements I wanted to include, and the themes started to reinforce themselves. At that time as well I was really into Anglo-Saxon history and old English myth, so those elements all got folded into the series as well. Then my publisher suggested that I “age up” the story, so I ended up writing it for the adult market. And I’m glad I did, that gave me an opportunity to tell a much more complex story than I originally had in mind.

How has the series been received so far?

Really, really well. I was worried that people wouldn’t respond to something that was so intricate and subversive of very established Fantasy conventions. I was worried people wouldn’t accept dual male/ female main characters with as many flaws as I loaded onto them. But readers have really responded. I get more enthusiastic comments from women than men, which is great. There is still a dearth of fiction with strong, realistic women in it. I wrote this series like it would be my last Fantasy series ever, and I loaded it with enough ideas and themes to reward repeat reading – and I’m probably more surprised than anyone that people are actually reading them twice, without the last book even being published yet. It’s beyond flattering.

What’s the most memorable praise you’ve ever received about your series?

The first that comes to mind was actually meant as criticism. One of the readers posted online that it was a confusing book because it was hard to know who to root for – the good guys weren’t always good and the bad guys weren’t always bad – and there was always too much going on so it was hard to put it down and leave it for a few days. I was like, right on! And that’s really been the only criticism the series, and I’m quite pleased with that. These are the things that books excel at. Movies are so streamlined in both of those senses, and that very truncated style of storytelling has crept into a lot of fiction as well. I find a character who is only good, who goes through a straightforward mission without any real challenge or difficulty rather unrealistic and, ultimately, very boring.

What is your writing process like?

Crazy-making. I honestly try to be as methodical as I can. I work 9-5 hours six days a week writing. Then at some point, usually within the last third of the book, everything becomes derailed and I frantically dash around trying to keep it all together, working every hour on it that I can to beat the deadline. Then I start editing it and things get even more hectic. I’m a ruthless self-editor and I do that as I go along. I routinely cut out entire chapters from my books if I think they’re slowing the story down even a little. For book two I cut out an entire 12,000 word section from the first half. Pfft! Gone in a keystroke.

What can we expect for the future of the series?

After Book 3 ends? Not a lot! Book 3 is the absolute last part of the story, and you see exactly why there can never be a sequel once you read the last chapter. Which is a shame because when this was going to be a five-parter for teens I had planned an entire book that pretty much just took place in the Faerie land that I created. I had to cut that up and parcel it out in all three books and there was more I wanted to say there. It would be nice to spin something out of that, but I don’t know what story I would tell so I don’t think that will happen. As far as ‘The Realms Thereunder’ are concerned though, I’ve left it all on the field with this last one.

How do you view the current state of Speculative Fiction as a genre and where do you think it’s headed?

I think it’s very healthy at the moment. I doubt that hardcore SF has ever had such a wide exposure, even in the heydays of the 60s and 70s. Plus, looking at it purely as a genre, you can see it influencing just about every artistic medium, not only books but comics, movies, TV, everything. As far as SF&F books themselves are concerned, I think they’re heading where they’ve always been heading – straight to the core of our identity as human beings. That’s always what SF&F has been – not about robots, or aliens, or the future – it’s always been about us, people, right here, and right now. All that other stuff is just to show us more perfectly in contrast. We live in a world right now that is more futuristic than something written over fifty years ago, yet the entire canon of the genre is still absolutely relevant. The technology we buy today we receive with instructions on how to use it, but not why we should use it, or if it is right for us to use it, or what will happen to us if we use it too much. This is something that SF started discussing right from the start – the morality and the natural consequences of comfort and convenience; the end product of self-help and cell phones. Speculative Fiction has never been more important than now, and I’m encouraged that people are paying attention to it.

March 29, 2014

The FEARFUL GATES released today

The last instalment of my fantasy trilogy is being released today. Please visit my books page to find out how to order it.

The last instalment of my fantasy trilogy is being released today. Please visit my books page to find out how to order it.

This ends my eight-year quest to tell what I believe every fantasy story should tell. From the start I had two scenes in mind — the first one, a boy in a church, and the last one, the same boy confronting the enemy. I was working with some very powerful themes and with the help and aid of my publisher, I was able to bring the story to you in a state that was better than I could have possibly hoped.

I left it all on the field with this last one though. And although I hope you do, I doubt you’ll ever read an ending to any story that is like this one.

Ross Lawhead's Blog

- Ross Lawhead's profile

- 31 followers