Lydia Syson's Blog, page 8

November 25, 2013

Island of Last Hope

This photograph shows a group of Polish fighter pilots walking away from a Hawker Hurricane in October 1940, probably at RAF Northolt in West London. They were apparently photographed after a sortie – one of over a thousand made in the first six months alone of Squadron 303′s formation. The expressions on these young men’s faces are mixed – relief, uncertainty, perhaps even surprise and joy that they are actually still alive.

There’s a myth that the Polish Air Force was destroyed on the ground within days of Hitler’s invasion of Poland on 1st September 1939. In fact, despite their outnumbered and out-of-date planes, Poland’s highly trained pilots fought bravely for several weeks before accepting defeat. By 17th September, the country ‘first to fight’ had been invaded by Russia from the East, and would soon be doubly occupied. But for the pilots the battle was far from over.

Poster designed in 1942 by Marek Żuławski, a Polish expressionist painter and graphic artist who settled in London in 1936.

Descriptions of their departure from Poland make heartbreaking reading. Adam Zamoyski, author of The Forgotten Few: The Polish Air Force in World War II, reckons that about 80% of the PAF survived the first Blitzkrieg of World War Two and managed to escape capture. 9,276 crossed the border into Rumania (not all as easily as Henryk in That Burning Summer), 900 fled to Hungary, about 1,000 escaped via the Baltic states of Lithuania or Latvia, and another 1,500 were captured by the Soviets and sent straight to labour camps. The aim was to regroup in France.

By late December, 1939, Michal Leszkiewicz, a future Bomber Command pilot who had escaped from Poland via Rumania at the age of 23, was sailing along Asia’s shoreline. He recorded in his diary: ‘We’re probably sailing to Syria. A vague fear of the unknown – a purely human instinct. When you know what to expect, you don’t go to pieces. We have to – we must go on. The responsibility lies with us, the young people; they’re turning to us even in Poland – the innocent ones whom fate has wronged . . .we are their hope.’

Despite his great love and commitment to his homeland, Michal Leszkiewicz never again returned to Poland, and died in England in 1992. His diary made a huge impression on me when I was finding out about the extraordinary odysseys so many airmen made before they reached Britain. I drew on his account for my descriptions of Henryk’s sea voyage from Bulgaria to Beirut, his arrival in the Middle East, the journey to France, and his frustration at the chaos there. On arrival, he found himself interned in miserable conditions in France with refugees from the defeated Spanish Republic.

By June 1940, France too had fallen. The remaining Polish airmen were evacuated to Britain. Arriving exhausted and battleweary in the only allied country left unoccupied in Western Europe, they called it ‘The Island of Last Hope’. On 18th June, Churchill famously declared: ‘Hitler knows that he will have to break us in this island or lose the war. If we can stand up to him, all Europe may be freed and the life of the world may move forward into broad, sunlit uplands.’ J.B.Priestley (‘That Yorkshire man on the radio – the one with the calming voice Aunt Myra loved to listen to’ TBS, p. 100) remembered the Germany he’d known and loved before the last war, and warned ‘any country that allows itself to be dominated by the Nazis will not only have the German Gestapo crawling everywhere, but will also find itself in the power of all of its own most unpleasant types – the very people who, for years, have been rotten with unsatisfied vanity, gnawing envy, and haunted by dreams of cruel power. Let the Nazis in, and you will find that the laziest loudmouth in the workshop has suddenly been given the power to kick you up and down the street, and that if you try to make any appeal, you have to do it to the one man in the district whose every word and look you’d always distrusted.’

Heinkel 111s in the Battle of Britain

The forty Polish pilots who took to the skies at the beginning of the Battle of Britain were scattered at first among a number of RAF squadrons. Most were among the 2,000 or so airmen who’d been kicking their heels in Britain for months already. When the earliest pilots first arrived, between December 1939 and February 1940, they were given a frustratingly slow induction into RAF life, involving English lessons, education in the King’s Regulations, and endless parades and rollcalls: it seemed they would never be allowed near an actual plane.

Zamoyski’s account of the clash of military cultures between British and Polish pilots makes fascinating reading. The Poles were driven to distraction by British officers – ‘ostriches’, they called them – who seemed to be hiding their heads in the sand about the real nature of the threat from Germany. The British, meanwhile, were disconcerted to say the least by the newcomers’ manners:

‘The Polish habit of saluting everyone, on station, in town, in restaurants, irritated the British officers, who found that they could not cross the airfield or walk down a street without acknowledging several dozen salutes. “They were always giving you salutes even if it was their despatcher handing you a cup of coffee,” recalls an RAF officer. ”The heel-clicking that went on was terrific,” remembers one RAF fitter, “and they had a funny way of bowing stiffly, from the waist up, like tin soldiers.”‘

Despite this, the Poles did not take easily to the kind of hierarchical deference traditional in the British military. Group Captain A.P.Davidson, a former air attaché in Warsaw and the station commander at RAF Eastchurch, near Sheerness, where the first Polish airmen were based, was shocked and baffled by their attitudes:

“Whilst on the one hand there exists a distinct class feeling between officers and airmen and the former often treat the latter with a lack of consideration unknown in our own Service, on the other hand, officers fraternise with airmen, walk about and play cards with them.”

Morale improved once the Poles were finally allowed to fly, but then they discovered that everything on a British aircraft was back-to-front, so all their reflexes had to be reversed. You had to push instead of pull to open the throttle, and even the toggle for opening the parachute was on the ‘wrong’ side. There was also the difficulty of judging in feet and miles, not metres and kilometres, and new navigational aids to master like radar (only just adopted, and still secret) and radios. The British tactic of close formation flying seemed suicidal to the experienced Poles, for pilots had to pay far more attention to not colliding with each other than looking out for attacking aircraft. Four tight ranks of three planes were supposedly protected by the middle plane of the last rank, known as the ‘weaver’, but 32 Squadron, based at Biggin Hill, lost 21 of these pilots in three weeks, each ‘picked off’ by the enemy without the rest of the squadron even noticing.

A myth that came to dominate war films and popular memory was that all Polish pilots were reckless and individualistic. The stereotype arose partly because they were trained to fire at much closer range than British pilots – almost at pointblank. (‘Those crazy Poles’, thinks Peggy,That Burning Summer, p. 43). This scene from the 1969 film The Battle of Britain (whose uncountable stars included Laurence Oliver as Hugh Dowding and Trevor Howard as Keith Park) is typical of British attitudes:

(Incidentally, and somewhat chillingly, the German aircraft used in this film were provided by Franco’s Spanish Air Force: a mixture of Heinkels, still used for transport, and retired Messerschmitt 109s.)

In August 1940, two new Polish fighter squadrons were formed: No. 302, ‘City of Poznań’, and No. 303, ‘Kościuszko’. By 1941 a fully-fledged Polish Air Force was operating alongside the RAF. By the end of the war, Polish pilots had won 342 British gallantry awards, and 303 Squadron claimed the highest number of kills of all the Allied squadrons in the Battle of Britain yet its death rate was the lowest.

On 11th September 1940 at 16.15 hrs, Sergeant Stanisław Duszyński was shot down over Romney Marsh, not far from Lydd, while attacking a Ju 88. He was 24, and like Henryk in That Burning Summer, had initially been evacuated to Rumania in 1939. Neither his body nor his Hurricane were recovered at the time, although unsuccessful efforts, both official and unofficial were made in 1973 and 1996. Six months later, Pilot Officer Bogusław Mierzwa’s Spitfire came down in flames on the stony promontory of Dungeness, not far from the lighthouse. Another pilot of the 303 Squadron, Mieczyslaw Waskiewicz, crashed into the sea off the point and was never found. Both were returning from a mission to escort six Blenheims sent to bomb a fighter airfield in France. Mierzwa had been awarded his Pilot’s Wings in Poland less than two years earlier, at the age of 22, not three months before the invastion of Poland. This tattered Polish flag still flies over the spot where his aircraft burned.

On 11th September 1940 at 16.15 hrs, Sergeant Stanisław Duszyński was shot down over Romney Marsh, not far from Lydd, while attacking a Ju 88. He was 24, and like Henryk in That Burning Summer, had initially been evacuated to Rumania in 1939. Neither his body nor his Hurricane were recovered at the time, although unsuccessful efforts, both official and unofficial were made in 1973 and 1996. Six months later, Pilot Officer Bogusław Mierzwa’s Spitfire came down in flames on the stony promontory of Dungeness, not far from the lighthouse. Another pilot of the 303 Squadron, Mieczyslaw Waskiewicz, crashed into the sea off the point and was never found. Both were returning from a mission to escort six Blenheims sent to bomb a fighter airfield in France. Mierzwa had been awarded his Pilot’s Wings in Poland less than two years earlier, at the age of 22, not three months before the invastion of Poland. This tattered Polish flag still flies over the spot where his aircraft burned.

Altogether, between 1939 and 1945, well over 200,000 Poles fought in all the forces under British High Command. But for complex reasons, by 1946, anti-Polish sentiment in Britain had become so bad that ‘Poles go Home’ graffiti was appearing near Polish Air Force bases. Squadron 318 Spitfire pilot Stefan Knapp, a sculptor and painter who suffered from recurring nightmares and insomnia for years after the war, recalled the change in his memoir, The Square Sun (1956):

‘I was choking with the bitterness of it…Not so long ago I had enjoyed the exaggerated prestige of a fighter pilot and the hysterical adulation that surrounded him. Suddenly I turned into the slag everybody wanted to be rid of, a thing useless, burdensome, even noxious. It was very hard to bear.’

In the programme for the Allied Victory  Celebrations in London a year later, you will only find a mention of Poland under one heading – the Central Band of the Royal Air Force. By this time it was Stalin, not Hitler, who seemed to require appeasement. The terrible fate of Poland, a subject too vast to tackle here and now, had already been determined around conference tables at Tehran, Yalta and Potsdam.

Celebrations in London a year later, you will only find a mention of Poland under one heading – the Central Band of the Royal Air Force. By this time it was Stalin, not Hitler, who seemed to require appeasement. The terrible fate of Poland, a subject too vast to tackle here and now, had already been determined around conference tables at Tehran, Yalta and Potsdam.

Find out more:

Adam Zamoyski, The Forgotten Few: The Polish Air Force in World War II (1995, Pen & Sword Aviation, 2009)

Lynne Olson & Stanley Cloud, For Your Freedom and Ours: The Kosciuszko Squadron – Forgotten Heroes of World War II, (2004)

Robert Gretyngier, in association with Wojtek Matusiak, Poles in Defence of Great Britain, July 1940-June 1941 (London, Grub St, 2001)

Josef Zielnski, Polish Airmen in the Battle of Britain, 2005 (A very useful book, with a short chapter on every airman, but not easy to get hold of)

Kenneth K. Koskodan No Greater Ally: The Untold Story of Poland’s Forces in World War II (Osprey, 2011)

Arkady Fiedler, 303 Squadron: The Legendary Battle of Britain Fighter Squadron (2010)

F.B.Czarmomski, They Fight for Poland: The War in the First Person, (1941 – Front Line Library)

Patrick Bishop, Fighter Boys: Saving Britain 1940, (Harper, 2003)

Jonathan Falconer, Life as a Battle of Britain Pilot, (The History Press, 2007)

Battle of Britain monument…find out about the Polish airmen.

RAF Museum online exhibition on Polish Pilots

Polish Institute and Sikorski Museum

Commemorative site with information to help find all the cemetaries in the world where Polish airmen were buried during WW2

Battle of Britain heritage trail

Further background reading and links for That Burning Summer can be found here. You can buy a ‘For Freedom’ T-shirt commemorating all the Polish aircrew killed in the Battle of Britain from Philosophy Football.

Identification of pilots in first photograph, left to right, in the front row: Pilot Officer Mirosław Ferić, Flight Lieutenant John A Kent (Commander of ‘A’ Flight – Kent wrote out phonetically on his trouser leg the Polish words for every procedure involved in take-off, flying and landing) , Flying Officer Bogdan Grzeszczak, Pilot Officer Jerzy Radomski, Pilot Officer Witold Łokuciewski, Pilot Officer Bogusław Mierzwa (obscured by Łokuciewski), Flying Officer Zdzisław Henneberg, Sergeant Jan Rogowski and Sergeant Eugeniusz Szaposznikow. In the centre, to the rear of this group, wearing helmet and goggles is the infamous F.O. Jan Zumbach.

November 14, 2013

28th February 2014: visit to Sydenham School, Lewisham

I’m looking forward to discussingThat Burning Summer, Britain’s Polish allies, the experience of invasion and much more with some of Sydenham School‘s keenest readers. NB This is not a public event, but you can book me for an event by contacting Authors Aloud on 01727 893992 or emailing info@authorsalouduk.co.uk

9th January 2014: Teenage Reading Group launch

Inspirational writer Sam Osman and I will be at Petts Wood Library from 6.30-7.30 pm to launch Bromley’s Teenage Reading Group on behalf of CWISL. If you’re aged 13-16 and enjoy reading and sharing the books you love, do come along! Meetings take place on the first Thursday of every month. Contact librarian Jenny Hawke on 01689 821607 to find out more.

November 13, 2013

Channel Radio Competition

Romney Marsh’s 24/7 radio station, Channel Radio, and Kent law firm Gullands are offering a copy of Romney Marsh set THAT BURNING SUMMER in a Twitter competition. Just follow @Gullands_HR_Law with #businessbunker (that’s the name of the programme) and look forward to the announcement of the winner on Tuesday 4th Feb. (Thanks to Amanda Finn!)

Amanda @gullands_HR_law @OI_RoyaCroudace @jododds on #businessbunker show today pic.twitter.com/ljjjHVm8cP

— Paul Andrews (@vanillaweb) January 28, 2014

November 12, 2013

The return of Asterix: the Verdict

The first hint was an intriguing question in the Guardian Quiz (no. 3), then a query on Twitter. Just in time for half-term, we finally got our hands on Asterix and the Picts, the first new book in the series to be created by an entirely new writing/drawing team.

We are a family of fervent Asterix-lovers. When my partner and I met, our amalgamated childhood collections ensured that our four children could be brought up in decent Goscinny-and-Uderzo-style. And sure enough, one by one, they all got the bug. Their minds were expanded, their vocabularies enlarged (“‘G’ is for Gluteus Maximus” – according to one son’s Year 3 Literacy Book) and their sense of humour sharpened. We even went to Parc Asterix. Twice.

So how has the new team of Jean-Yves Ferri and Didier Conrad lived up to the original creators?

Over to my children, three of whom agreed to take part in this family review…

Son 1 (aged 14 – favourite: Asterix and the Mansion of the Gods)

‘The art was excellent. However the writing was not as funny as the previous books and the puns were far worse. The storyline, although predictable, was fun, and the introduction of Scotland into the series was interesting. Overall, it was a good book on its own, but had nothing on the previous books.’

Son 2 (aged 10 – favourite: Obelix and Co)

‘Asterix and the Picts had the same wonderfully brilliant illustrations that all of the other books had. I really liked the storyline, as I have always wanted more Asterix books around that area, but unfortunately, the jokes weren’t quite up to Asterix standard. The book felt like a lot of it was in Gaul, and they didn’t quite stay in Scotland long enough. I was rather disappointed, but I do think that Orion should publish more of them: I would still rather have a quite good book than none at all, and it was still an amazing book.’

Son 3 (aged 10 – favourite: Asterix and the Golden Sickle)

‘I was really surprised when I realised that the drawings weren’t drawn by Uderzo. After a long time of reading the same Asterix books again and again, I had got bored, so I was very excited when this book came out. I felt that it had the same Asterix feel to it, and I enjoyed the book thoroughly. I particularly liked Nessie, and all of the different clans.’

As a bit of a purist, I must admit I’ve always favoured the first 24 books in the series, which were written before the death of Goscinny, after which Uderzo valiantly continued solo for another ten. But I’m pleased to say that Anthea Bell, one of the original translators, whose utter genius translated Idéfix into Dogmatix, has remained on board throughout, and that continues to make a big difference.

The very high standard of wit in the earliest Asterix books is extremely hard to live up to, but Asterix and the Picts clearly hits the mark in other respects. There were some memorable gems, and a good balance between tradition and innovation. I loved Obelix’s predictable enthusiasm for tossing the caber and the new names – a couple of Romans called ‘Fallacius’ and ‘Pretentius’ and some great ‘Mac’ variations. Not to mention the Pictograms. If you’re after perfection, you may be disappointed, but this family is more than happy to settle for the pleasure of catching up with old friends, and looking forward to further adventures to come.

October 31, 2013

The Comfort of Fellow Writers

Today marks my first ever contribution to a blog that I’ve found both addictive and invaluable for the past few years. I’ve written a guest post called ‘Guilty Pleasures’ for ‘An Awfully Big Blog Adventure – the ramblings of a few scattered authors’ about the influence of 1940s films on the writing of That Burning Summer.

So do go and read that, there, and tell me what you think….and meanwhile, here, I’ll take the opportunity to sing the praises of the world of children’s books. Ever since I’ve been writing for children/young adults, I’ve been amazed and grateful for the support I’ve had from fellow authors and illustrators. Maybe every writing world is like this, in its own way, but somehow I suspect not.

I’m tempted to gush at length now, but I’ll resist, and simply say thank you, thank you, thank you all to the rippling circles of writers who have offered encouragement, advice, reassurance, comfort, hope, reflection, humour and much more over the last year. I’ve met them in the flesh and virtually, formally and informally, through my small writing group, through my publisher (Hot Key Books) and my agency (Felicity Bryan Associates) and thanks also to a series of more or less pronounceable acronyms – the ‘other’ SAS (the Society of Scattered Authors – responsible for an Awfully Big Blog Adventure in public, and the children’s writers forum Balaclava in private), SCBWI, the CWIG of SoA, and CWISL. Having committed myself to a profession which perhaps has more dramatic ups and downs than many, or perhaps is simply practised by people with a tendency to dramatise them, which can one day feel too good to be true, and the next leave you in the depths of despair, this has been been one of the most enjoyable and unexpected pleasures.

October 18, 2013

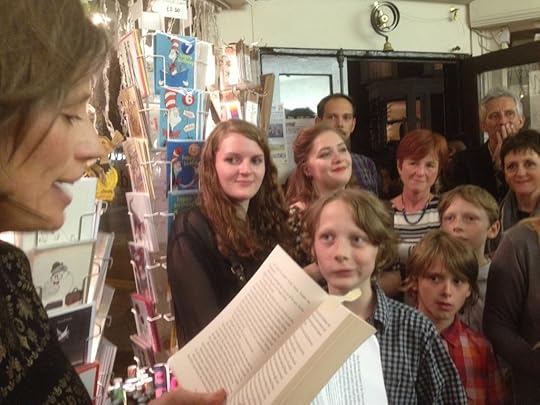

News and Pictures

Huge thanks to everyone who came to Review bookshop to welcome That Burning Summer into the world on October 4th – was that really a fortnight ago? And was it really only a year since we’d been at Cable Street, singing and celebrating the birth of A World Between Us, Hot Key’s fourth ever title?

As I explained before reading from the book, That Burning Summer is far from a sequel, but it’s definitely a companion to A World Between Us. From epic battle scenes the length and breadth of Spain, we move, a few years later, to small town claustrophobia in Kent. The storm we saw gathering in the first book, which our gallant volunteers for liberty had tried so hard but failed to prevent, has reached the shores of Britain: from Romney Marsh, the guns in France are all too audible and invasion is imminent.

It’s easy to forget, now that the idea of ‘our finest hour’ dominates the story the nation tells itself about the summer of 1940, how close it came to being ‘our darkest hour’. This was a time when everything hung in the balance, there were rumours of spies all around, and you didn’t know who you could trust. It was a summer of fifth columnists and parachuting nuns, evacuated sheep and buried planes, and no stranger could be trusted. And of course, far from being Britain’s second language, Polish was utterly unfamiliar…

The first reviews and book bloggers’ responses have now started to appear, and very lovely they’ve been too. This week I’ve been talking about my muses with fellow-Bonnier author Katherine Roberts, delighted to be a Muse Monday guest on her Riding the Unicorn website. In the next few weeks, I’ll also be answering questions at My Book Corner and guestblogging at An Awfully Big Blog Adventure (The Ramblings of a few Scattered Authors - yes, I’m a proud member of the ‘other’ SAS).

But now, back to that launch party….

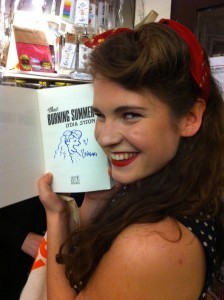

It was a particular pleasure to be able to introduce Jan Bielecki to some of his adoring fans, and thank him in person and in public – time and again I hear that it was his covers that have attracted readers’ attention to both A World Between Us and That Burning Summer.  It’s not often you get the chance to have a YA novel signed by its illustrator – and in such style too!

It’s not often you get the chance to have a YA novel signed by its illustrator – and in such style too!

Thank you so much to Olivia Mead (right), Cait Davies and Sanne Vliegenthart from Hot Key, as well as Phoebe Finn, Iris Mathieson and Lila Bernstein who all looked wonderful in their vintage costumes and hairdos (I’ll be adding more pictures soon) and were also immensely helpful in making sure that everyone had all the nourishment a swinging Battle of Britain themed party requires…in this case, Polish food….

…and Spitfire ale, from the heart of Kent.

And yes…that was indeed Evie Wyld you spotted behind the till, anemones and beer bottle. This year she was named as one of Granta’s Best of Young British Novelists…hurry back to review for signed copies of her John Llewellyn Rhys Prize winning first novel, After the Fire, A Still Small Voice and All the Birds, Singing, which has also had amazing and well-deserved reviews. Lots more thanks to Evie for hosting the party with such warmth – my third book event at this most wonderful bookshop.

(Such good taste in London books – look – there’s the brilliant Bumper Book of London lurking just below That Burning Summer. I’m in a very supportive writing group with Becky Jones, one of its authors, and also Amanda Swift, co-writer of the Guinea Pigs On Line series, who were at review, along with a number of my fellow CWISL authors – in fact, I have Bridget Strevens Marzo to thank for many of the photographs I’m posting here now.)

Come back soon to find out more about the true stories that inspired That Burning Summer.

October 10, 2013

THAT BURNING SUMMER reviews

Please follow links for full reviews:

We Sat Down tweeted: ‘an endearing, provocative and thrilling second novel’

‘Once again, Lydia Syson’s teen fiction marries the thought-provoking nitty gritties of wartime with a tone that is celebratory in its joie de vivre….’ Read more

Teach Secondary magazine wrote:

‘In ‘A World Between Us’, her first award-shortlisted historic novel for teenagers, Lydia Syson proved she could tackle human dramas played out against vast historic panoramas. Here, she is equally assured portraying the claustrophobia of life in a tight-knit, increasingly regulated and selfpolicing community at that pivotal moment in the summer of 1940 when phoney war began to become very real indeed. The mysterious landscape of Romney Marsh is as intensely vivid a character as the novel’s protagonists: awkward younger brother Ernest, Peggy, his adolescent sister, and psychologically damaged Polish pilot, Henryk. The burgeoning romance between the girl and the older, vulnerable man is beautifully and unsentimentally handled; this is a great novel for all those who like their history free of cliché, and who value human experience observed with non-judgmental clarity.’

The Overflowing Library wrote:

‘Another fab read from Lydia Syson. I must admit I love Lydia’s work purely because it speaks to me as a history teacher. Her stories are engaging and exciting as well being well researched and historically accurate. I love that I can happily recommend them to my students without any worries that might get completely wrong ideas about the time we are studying.’ Read more

Stepping Out Of the Page wrote:

‘I completely unashamedly fell for the gorgeous vintage-style cover of That Burning Summer before I knew what the book was even about (though the contents are portrayed pretty well on the cover, actually). I am so glad that That Burning Summer caught my eye. After finding out it was set in England during World War Two, I picked it up and absolutely devoured it…it was just so lovely to read.’ Read more

Books & Writers Jnr wrote:

‘a second brilliant YA novel from one of my favourite historical fiction authors!…Lydia’s created yet more unforgettable characters that I enjoyed reading about so much…One word to describe this? Unputdownable. It was such a great read, that I’m definitely going to be recommending to anyone I know who likes historical fiction!’Read more

October 3, 2013

New book, new look!

I’m delighted with the new design of this website – huge thanks to Jan Bielecki and Cait Davies in particular for making it happen. And on a day which is anything but burning or summery, it has been lovely just now to walk into a nearby bookshop and see a copy of my newborn title nestling happily on the shelf next to A World Between Us. The shop was Dulwich Books, as it happens (as you may

know, here in South East London we are spoiled for choice for splendid independents), where we had a conversation about the age range of That Burning Summer‘s readership and decided unanimously that it was definitely one to recommend to both under and over-12s.

Do visit the Hot Key blog and watch the new That Burning Summer videos.

- Rumours generated by Britain’s Underground Propaganda Committee (UPC) were codenamed ‘sibs’ – the most famous of these was that the British had a new way of setting the sea on fire.

- From late 1939, the British government spied on its own people, using secret eavesdroppers in pubs, factories and on buses all over the country to collect rumours which were sent to Whitehall to be analysed.

- Four enemy spies landed on the coast of Kent in the summer of 1940 – all were caught red-handed.

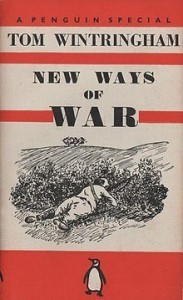

- Tom Wintringham, former British Battalion Commander in the Spanish Civil War, opened the first Home Guard training school at Osterley Park in 1940, staffed by International Brigade vets and Spanish explosive experts, but he was never allowed to join the Home Guard himself because membership was barred to Communists.

- Over 200,000 Poles fought under British High Command between 1939 and 1945, but the only Poles to take part in the Allied Victory Celebrations in London in 1946 were musicians in the RAF’s central band.

Now buy That Burning Summer and re-live those days of doubt and uncertainty, when invasion was anticipated at any hour, and you never knew who you might find lurking behind your chickenshed….

October 1, 2013

Journey to Hill 481

Last week’s experience of visiting some of the settings for key events in A World Between Us was extremely powerful. It’s certainly a strange sensation to go to a real place for the first time after having imagined it so intensely and for so long. These are all places of real and terrible tragedies, but it’s important not to forget that hope and idealism are equally significant elements in their histories.

I thought I might feel frustration and regret at an opportunity missed, or chastise myself for what I’d left out or got wrong. Perhaps I’m finally far away enough from the writing process to look back with just a small sigh of que sera sera. Anyway, as it turned out, almost exactly a year since the story of Felix, Nat and George was published, I found myself enjoying a kind of recognition I’d not encountered before, and felt I’d come at last to the Ebro with a richness of knowledge and understanding I could never have brought with me at an earlier stage of researching and writing the book. Of course I thought a lot about my imaginary characters while I was in Spain. But I felt more involved still with the real people who had originally inspired A World Between Us, details of whose stories continue to emerge even after their deaths.

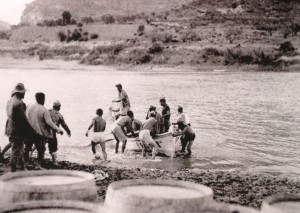

Between the commemorative events at the cave hospital at La Bisbal de Falset and those at Corbera Old Town we went to the wooded banks of the Ebro river, near Ascó, a stone’s throw from the  spot where Nat crossed in darkness before the well-planned and much-anticipated attack on Nationalist territory in July 1938.

spot where Nat crossed in darkness before the well-planned and much-anticipated attack on Nationalist territory in July 1938.

‘Even after night has fallen, heat rises from the dry earth with a force you can wade through. The river is cooler, almost cold. Nat feels its darkness swirl and eddy against his fingertips as he grips the side of the small boat, so low in the water that it sets his nerves jangling. He’s never learned to swim. The Ebro is deep and broad, and its currents are strong.’

A World Between Us, p. 225

On a sunny late summer day, under blue skies unthreatened by aviones, the speed and width of the river still looked daunting. I stood on a pontoon alongside people whose own parents had been rowed into enemy territory that stifling night, and wondered. Many of the Brigaders who took part in this offensive had been forced into the Ebro’s fast-flowing waters just a few months earlier, during the chaos and terror of the Retreats. John Longstaff had been the very last across the bridge at Mora de Ebro before it was blown up by British engineer Percy Ludwick and his team, and never the urgent cries of ‘Venga! Venga!’ as he sprinted to safety. Former Olympic rower Lewis Clive, who was later killed outright on Hill 481, had swum across with one non-swimmer, and returned to rescue military equipment. Others were swept away by the current

Duncan Longstaff, the main organiser of this IBMT tour of the Ebro, was one of many who told me last week of the frustration of how little his father had spoken about the Spanish Civil War when he was growing up. A common lament – which I share in relation to my own grandparents and their anti-fascist activities in London – was not knowing the right questions to ask at the right time. I’d first encountered John Longstaff in the sound archive of the Imperial War Museum. He was a former Stockton hunger-marcher who became a runner for the British Battalion and, if I remember rightly, like Nat, he first saw action at Jarama in February 1937. He recalled the drama of the wordless Ebro crossing in a written memoir:

We got into rowing boats; everyone was silent and thinking about the fighting to come. The Spanish and International Brigaders had muffled even the oars. I had a lot of equipment, rifle, about 100 rounds of ammunition and my blanket tied round my body. Inside the blanket I carried my few odd personal items, including an empty mess tin and a filled water bottle.

(quoted in Richard Baxell’s Unlikely Warriors: the British in the Spanish Civil War and the Fight Against Fascism)

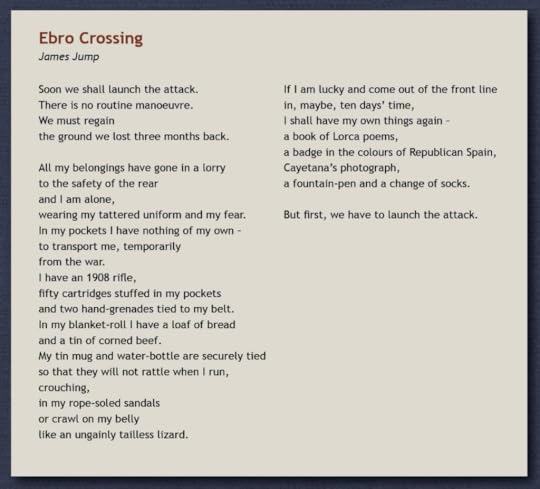

The muddle of anticipation, longing, disconnection and sheer fear of this moment was brilliantly captured by James Jump a poem which his son Jim kindly allowed us to use in the AWBU iBook:

‘Ebro Crossing’ by James Jump is one of a number of poems included in the multitouch iBook edition of ‘A World Between Us’ from the magnificent collection ‘Poems from Spain: International Brigaders on the Spanish Civil War’ by kind permission of the editor, Jim Jump.

‘

Night. They wait for news and hope for back-up. Men come, scrambling through the darkness. One has a vast reel of wire on his back, unspooling as he clambers up. With telephone contact, news filters through. Don’t move. We’ve got Gandesa almost surrounded. They’re waiting for us. Depending on us. Fresh ammunition? Food? Not much. The Fascists have opened the flood gates, you see. The Ebro is rising. Pontoons swept away, boats unmoored. Some mules on their way. A little water. Not enough. Cigarettes.

‘

Night. They wait for news and hope for back-up. Men come, scrambling through the darkness. One has a vast reel of wire on his back, unspooling as he clambers up. With telephone contact, news filters through. Don’t move. We’ve got Gandesa almost surrounded. They’re waiting for us. Depending on us. Fresh ammunition? Food? Not much. The Fascists have opened the flood gates, you see. The Ebro is rising. Pontoons swept away, boats unmoored. Some mules on their way. A little water. Not enough. Cigarettes.

The wounded are dragged away.’

A World Between Us, p. 236.

On Hill 481, where the pines are now thicker and the cover less sparse than it was in 1938, it is easy to see how horribly exposed the men were, as they repeatedly tried and failed to take this position from the Nationalists. It’s much further from the river than I realised, and the church tower at Gandesa from which the enemy also fired seems implausibly distant too. Rosemary still grows on the hillside. We have a moment of silence and reflection at the top, and then sing. Si me quires escribir…

In the new town of Corbera d’Ebre there is an impressive museum, one of a number of historical ‘spaces’ in the area known as the ‘Espais de la Batalla de l’Ebre’. It’s called 115 days. You get a real sense of what it was like to live through these days, from both a military and domestic point of view. Empty plates wait forever for food on the table of a kitchen that’s been abandoned in haste. A soldier writes a letter in a trench. Newspapers announce the Munich agreement. Suitcases are packed for flight. There is even a wooden crate which once held the ubiquitous condensed milk tins to which almost every nurse refers…the tins which became coffee cups, oil lamps, anything anyone could think of or need.

forever for food on the table of a kitchen that’s been abandoned in haste. A soldier writes a letter in a trench. Newspapers announce the Munich agreement. Suitcases are packed for flight. There is even a wooden crate which once held the ubiquitous condensed milk tins to which almost every nurse refers…the tins which became coffee cups, oil lamps, anything anyone could think of or need.

We were staying in Cambrils, at first sight an unexceptional seaside town on the Costa Dorada. But then I realised…all those stories told by volunteers of the slow train down the coast from Barcelona to the IB HQ at Albacete, a train so slow you could get out and pick oranges and hop back in, a train greeted by flowers and food and warm welcomes throughout its journey? It passed through here.

After the retreats the International  Brigade was headquartered at the castle here (now a restaurant) and during the battle of the Ebro, the wounded (John Longstaff included) were treated at the hospital which had once been a seminary. Thanks to Cambrils Museum historian Gerard Martí and archivist Montserrat Flores, who have spent years gathering material about the impact of the war in this area, we heard how local people now in their 80s and 90s still remember the arrival of the Brigaders in their village in their childhood – fresh vegetables and eggs were exchanged for precious tinned meat, a Christmas party was held, with a Brigadista assigned to each child and presents for all, and before battle, a mass was even celebrated in the chapel, attended by villagers and some of the Catholic Polish volunteers.

Brigade was headquartered at the castle here (now a restaurant) and during the battle of the Ebro, the wounded (John Longstaff included) were treated at the hospital which had once been a seminary. Thanks to Cambrils Museum historian Gerard Martí and archivist Montserrat Flores, who have spent years gathering material about the impact of the war in this area, we heard how local people now in their 80s and 90s still remember the arrival of the Brigaders in their village in their childhood – fresh vegetables and eggs were exchanged for precious tinned meat, a Christmas party was held, with a Brigadista assigned to each child and presents for all, and before battle, a mass was even celebrated in the chapel, attended by villagers and some of the Catholic Polish volunteers.

There were other surprises. At a time  when the worst excesses of anti-clericalism were being unleashed in Catalonia and Aragon in particular, the President of the Anti-Fascist Committee barred the door of the huge modern seminary where he’d been educated himself and insisted it should be saved from burning. (The brothers who taught there had already been safely hidden.) Of course the building made a perfect hospital, and to this day, little has been touched. As we stood in a glassed corridor, it was all too easy to imagine the amputated limbs raining down from the operating theatres above, witnessed in horror and never forgotten by a fourteen-year-old cook working in the kitchens below.

when the worst excesses of anti-clericalism were being unleashed in Catalonia and Aragon in particular, the President of the Anti-Fascist Committee barred the door of the huge modern seminary where he’d been educated himself and insisted it should be saved from burning. (The brothers who taught there had already been safely hidden.) Of course the building made a perfect hospital, and to this day, little has been touched. As we stood in a glassed corridor, it was all too easy to imagine the amputated limbs raining down from the operating theatres above, witnessed in horror and never forgotten by a fourteen-year-old cook working in the kitchens below.

(I wish I had time to include all the other stories from the Ebro I heard during this visit, such as those of the Yugoslav volunteer Danilo Lekic, Clarence Kailin and his best friend John Cookson. Do follow these links to explore further…these are people well worth finding out about.)