Lydia Syson's Blog, page 7

May 2, 2014

Writing competition results

Last month I wrote about a high-tech school visit I’d made to Sydenham School in South London. Today I’m delighted to announce the results of the creative writing competition. The theme was ‘invasion’, and the winning entry was by Jess Taylor in Year 8, who set her story – the opening chapter of a novel – in Poland, a month after it had been invaded by both German and Soviet forces. It’s atmospheric, dramatic, and definitely leaves you wanting to know what happens next.

Many congratulations to Jess and good luck with writing the rest of the novel!

October 1st, 1939

Five days before Poland is conquered.

Bombs. Falling. Left and right. Running, can’t stop. Quick! Duck! That was close. Now, get up! Don’t stop running. Never stop running again.

*

Where are the others? They aren’t here. I ran alone. They ran, but where? Where are Krystyn and Wira? Where are the boys? Where is Erek? He was supposed to keep us together. It looks like he failed at that.

I’m still running, but slower now. I’m tired, though I’ve gone much further then I would have before the invasion started. If the invasion has given me one good thing it has been my stamina, my wariness, my heightened senses. Now I trust no one without reason; I think of myself before others; my instincts protect me and me only. I suppose some people might call me dangerous… I was never dangerous before.

These days I am cold and hard steel, because the war has left me with nothing else to be.

*

Where is the group? It’s strange for me to have not even spotted one of them yet. The group used to be everywhere. It was annoying sometimes, their tendency to have an eye in every crowd and an ear in every wall, but it was how we managed to survive. At the moment I kind of wish that there as an eye watching me, because at least then I’d know that there was someone else alive, someone out there. Unfortunately I suspect they are dead back there, but somehow I don’t want to believe it.

We were moving slowly, together, in a pack. The night before had been a hard one, stressful. No bombs, but plenty of gunfire. Plenty of bodies.

We had been wondering about the lack of explosions, hoping that the Germans had finally discovered mercy, or even better, run out of projectiles. No-one anticipated the attack. No-one even thought that there would be one. There was nothing that we could do when the sky started to rain fire.

The photograph of a young boy in the ruins of Warsaw was  taken by Julien Bryan (pictured right, filming the ground-breaking documentary Siege). Find out more about the photographer and see more of his extraordinary images of the invasion of Poland on the Holocaust Encyclopedia of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

taken by Julien Bryan (pictured right, filming the ground-breaking documentary Siege). Find out more about the photographer and see more of his extraordinary images of the invasion of Poland on the Holocaust Encyclopedia of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

April 24, 2014

June 5th 2014: VANGO Book 2 launch and panel discussion

I’m delighted to be involved in this exciting event, which has been organised by IBBY, the International Board on Books for Young People, a non-profit organisation (with an official status in UNESCO and UNICEF) representing a world-wide network of people committed to bringing books and children together. It was set up to promote international understanding through children’s books, and give children everywhere the opportunity to have access to books with high literary and artistic standards. Thanks to IBBY, the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child includes an appeal to all nations to promote the production and distribution of children’s books. Find out more about IBBY and its work here.

All welcome – please share!

April 19, 2014

#UKYADay

I’m not going to assume that everybody who reads this will instantly understand the title of this post, but I have a feeling that in twenty or thirty years time, someone, somewhere, will be writing a thesis about the phenomenon that is UKYA. And nobody will need an explanation.

Almost exactly two years ago, three indefatigable writers – Keris Stainton, Susie Day and Keren David – launched the groundbreaking UKYA site. Its tagline is ‘Celebrating Young Adult fiction by UK authors’ and that’s exactly what it does: it’s a browsable showcase of novels set in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, or by writers based or born on these shores. I think it’s fair to say that it had its origins in the slight sense of despair many writers had that whenever you went into a bookshop, its YA/teen shelves were overwhelmingly dominated by US fiction. I also think that’s beginning to change, and this has partly been thanks to the incredible enthusiasm of UK teen book bloggers – a diverse and sociable crowd, some teenagers, some older, but all passionate about reading and spreading the word about the books they love.

Last September one of them, Lucy Powrie aka @LucytheReader, set up Project UKYA, and since then she’s been energetically organising monthly campaigns (or ‘projects’) to raise awareness of UK YA fiction and authors in all kinds of innovative and exciting ways. Today, #UKYADay, is her brainchild. It’s been heartwarming and inspiring to see the day-long celebrations on blogs and tweets (and just about every other form of social media too) from writers, readers and reviewers up and down the land. You’ll find book recommendations, giveaways, quizzes, reviews, interviews, discussion and general fanfare.

And best of all, this is just the start of it.

Here’s just a small selection of today’s UKYA DAY posts, from Keren David, Helen Grant, The Whispering of the Pages, YA Yeah Yeah, Fluttering Butterflies and An Awfully Big Blog Adventure.

You’ll find the websites of many more of the bookbloggers who’ve done so much to promote UKYA by following the links on my review pages for A World Between Us and That Burning Summer. Thank you, everyone!

My own UKYADay treats are:

- a manuscript by a fellow UKYA writer, which will be on the shelves next year, I think. So I’m keeping that under my hat, but here’s a big clue about its authorship.

- a manuscript by a fellow UKYA writer, which will be on the shelves next year, I think. So I’m keeping that under my hat, but here’s a big clue about its authorship.

- the last, painfully sad chapters of ‘The Little Prince’  (bedtime reading to my youngest children, soon-to-be-young-adults)

(bedtime reading to my youngest children, soon-to-be-young-adults)

- the end of a nail-biting historical thriller, Vango.

- the end of a nail-biting historical thriller, Vango.

(UKYA includes UK translations, doesn’t it? Doesn’t it? Discuss….)

April 7, 2014

Diving deeper: into the ‘Glass Room’

Writing historical fiction demands total immersion. It’s a fairly obsessive process, but well worth it. Bit by bit, you build up an increasingly accurate and nuanced picture of the world your characters inhabit, discover what makes them tick, what might affect the way they think and feel about events. Not surprisingly, I was immediately intrigued when I was invited to use the new ‘immersion room’ at Sydenham School, London, for a planned event with some of their year 8 and 9 students.

I already knew that I’d be talking to a group of girls who had read That Burning Summer in advance. This always makes an author visit particularly rewarding: it’s fantastic to be able to discuss the book in depth, to find out how different readers react to particular characters and plot twists, or how their reading has affected their perspective on a particular historical moment. I thought that the immersion room would offer a chance to add another whole layer to the event, but I wasn’t at all sure what I was actually dealing with. Hearing that it was known as ‘the glass room’ added a small extra twist. When I was researching ‘Lack of Moral Fibre’, the RAF’s cruel label for flying fatigue (post-traumatic stress disorder) during World War 2, I discovered that  ‘the glasshouse’ was the common name for a military prison, and the destination of many World War Two deserters, including pilots like Henryk. Thankfully, the resemblance ended with the name, as I found a few weeks before the event, when I went to check out Sydenham’s immersion room with Diana Adams, Learning Resource Manager, and Huong Nong, one of the school’s brilliant IT specialists.

‘the glasshouse’ was the common name for a military prison, and the destination of many World War Two deserters, including pilots like Henryk. Thankfully, the resemblance ended with the name, as I found a few weeks before the event, when I went to check out Sydenham’s immersion room with Diana Adams, Learning Resource Manager, and Huong Nong, one of the school’s brilliant IT specialists.

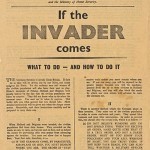

I had three screens to play with simultaneously, one of them interactive, which meant I could draw or write on it too and this proved particularly useful for annotating maps. I could use video images as well as stills. And I could also use sound, and even a visualiser, which would allow the projection of actual items in my hand onto a screen. Thanks to the super-smart copier in the school’s IT department, I was able to scan a lot of my material, such as reproduction newspapers, maps, posters and the crucial leaflet which sets off Ernest’s fears of invasion in That Burning Summer. This is an original copy I tracked down on Ebay, so it was great to be able to reproduce it in a way that allowed every student to have a copy in their hand. I suggested using it as the basis for follow-up work in the form of a creative writing competition.

I had three screens to play with simultaneously, one of them interactive, which meant I could draw or write on it too and this proved particularly useful for annotating maps. I could use video images as well as stills. And I could also use sound, and even a visualiser, which would allow the projection of actual items in my hand onto a screen. Thanks to the super-smart copier in the school’s IT department, I was able to scan a lot of my material, such as reproduction newspapers, maps, posters and the crucial leaflet which sets off Ernest’s fears of invasion in That Burning Summer. This is an original copy I tracked down on Ebay, so it was great to be able to reproduce it in a way that allowed every student to have a copy in their hand. I suggested using it as the basis for follow-up work in the form of a creative writing competition.

Planning the event was quite daunting, but also a lot of fun, and took me back a little to my radio- producing days, with Huong taking on the role of a studio manager or SM. I realised I’d be breaking nearly all the rules of the author event training I’d recently received from Author Profile thanks to the National Literacy Trust’s 21st Author Programme – well, quite a lot of them anyway! I couldn’t exactly rehearse and I was completely dependent on technology. We gathered together all sorts of material: a  sequence of photographs of Romney Marsh itself, taken while I was writing and researching the book (including a letter from the RAF to the mother of a young pilot whose plane vanished Kent); a series of propaganda posters; newspaper coverage of period, including the announcement of the ‘If the Invader Comes’ leaflet; clips from The Battle of Britain film made in 1969, without which many of the original Spitfires and Hurricanes would never have been preserved; music from the film Dangerous Moonlight (find out why here); and images from Humphrey Jennings‘ extraordinarily moving documentary, Words for Battle. In other words, just the kind of materials which made the summer of 1940 come alive for me while I was writing That Burning Summer. Over the next weeks Huong did a brilliant job of putting it all together in the sequence I needed for each screen, and we had a final run-through and re-jig first thing in the morning of the event, so that I could get the hang of the remote controls.

sequence of photographs of Romney Marsh itself, taken while I was writing and researching the book (including a letter from the RAF to the mother of a young pilot whose plane vanished Kent); a series of propaganda posters; newspaper coverage of period, including the announcement of the ‘If the Invader Comes’ leaflet; clips from The Battle of Britain film made in 1969, without which many of the original Spitfires and Hurricanes would never have been preserved; music from the film Dangerous Moonlight (find out why here); and images from Humphrey Jennings‘ extraordinarily moving documentary, Words for Battle. In other words, just the kind of materials which made the summer of 1940 come alive for me while I was writing That Burning Summer. Over the next weeks Huong did a brilliant job of putting it all together in the sequence I needed for each screen, and we had a final run-through and re-jig first thing in the morning of the event, so that I could get the hang of the remote controls.

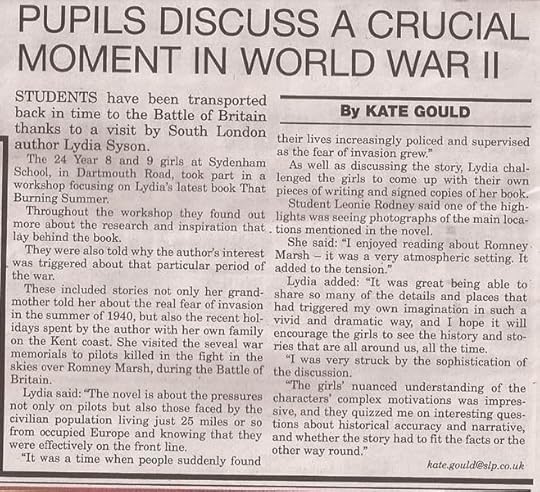

The multi-screen experience wasn’t very easy to photograph while it actually took place, as I’m sure you can imagine. But it seemed to work extremely well, the girls responded with great enthusiasm, and the South London Press came along and captured the spirit of the event, as you can see from their generous coverage below. Now I’m looking forward to receiving the entries for the writing competition.

The multi-screen experience wasn’t very easy to photograph while it actually took place, as I’m sure you can imagine. But it seemed to work extremely well, the girls responded with great enthusiasm, and the South London Press came along and captured the spirit of the event, as you can see from their generous coverage below. Now I’m looking forward to receiving the entries for the writing competition.

You’ll be able to read the winning entry here soon. For more information about my school visits and other events, please contact Authors Aloud.

March 2, 2014

Len Crome Memorial Lecture 2014: Taking Sides

The Spanish Civil War ‘gripped the imagination of a generation’, said Valentine Cunningham this weekend at Taking Sides: Artists and Writers on the Spanish Civil War. To judge from the huge and variously-aged turnout at the event, not to mention the responses I’ve had from young readers of my own novel on the subject, it will continue to do so for several generations to come. Perhaps, suggested conference chair Mary Vincent in her closing remarks, the subject is still so compelling because it represents better than any other conflict the terrible paradox of a just war, or perhaps it is because this particular war, and the cultural productions it inspired, embody modernity. Manus O’Riordan offered as an explanation the humanity in the literature of the SCW, citing American volunteer Milton Wolff’s resurrection in fictional form of the deserter he had been compelled to execute in real life. Another contributor from the floor linked the ongoing exhumation of bodies in Spain with the rediscovery and fresh exploration by a new generation of a long hidden body of memoir and texts.

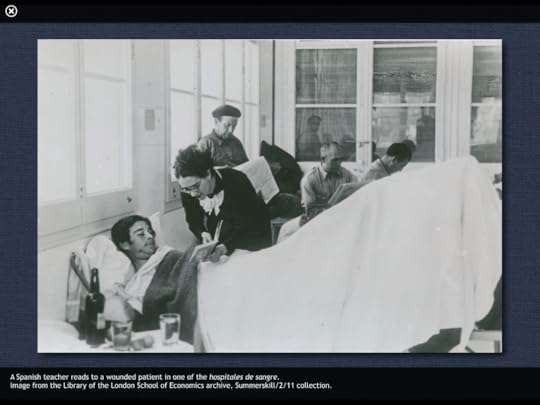

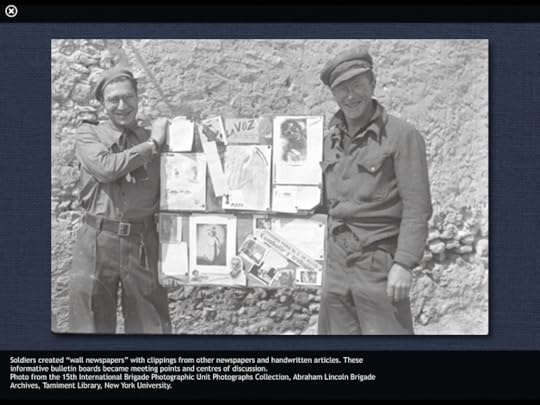

The Republican commitment to education and the arts was something I tried hard to convey in A World Between Us - literacy lessons in trenches and temporary hospitals, innovations in poster design, wall newspapers and cartoons. (You can see some illustrations from the iBook edition above and below.) Carl-Henrik Bjerström explained that the Culture Militias of the war were the direct descendants of the Second Republic’s Misiones Pedagogique in the early 1930s – cultural forays from Madrid into isolated rural communities, such as travelling art exhibitions introducing the work of Goya to the masses.

I think he surprised everyone with the fact that the budget for the Ministry of Public Instruction and the Arts was actually bigger than that of the Ministry of War, so great was the government’s commitment to the democratisation of culture – not to mention its confidence at this stage about winning the war. We saw an example of the use of inspiring slogans broken down into component parts and sounds – ‘luchamos por nuestra culture’ – we are fighting for our culture. This reminded me of Florent’s incriminating and revolutionary reading lessons in Zola’s Le Ventre du Paris and also, of course, Kitty teaching Spanish to Dr Smiley in the ambulance and Unity’s alphabet class in Teruel in A World Between Us. (Is this a technique Mr Gove might consider adapting, I wonder? Feel free to comment below with suggestions for suitable phonics slogans…)

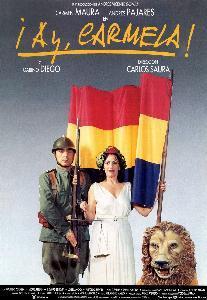

Carmen Herrero gave us a tantalising gallop through  the history and memory wars at work in the representation of the International Brigades in films of the 1990s. She also introduced a word and concept quite new to me: esperpento - the distortion of reality through black humour, typified by the work of both Goya and the filmmaker Carlos Saura in Ay Carmela (1990). I hope to be able to add her filmography and links to my further reading section very soon, and will certainly be following up her suggestions myself when I can – some are frustratingly hard to get hold of.

the history and memory wars at work in the representation of the International Brigades in films of the 1990s. She also introduced a word and concept quite new to me: esperpento - the distortion of reality through black humour, typified by the work of both Goya and the filmmaker Carlos Saura in Ay Carmela (1990). I hope to be able to add her filmography and links to my further reading section very soon, and will certainly be following up her suggestions myself when I can – some are frustratingly hard to get hold of.

Meanwhile, here’s a trailer for Combatidos (2011), a recent short film inspired by and set in an important ‘place of memory’, the trenches of Jarama.

After lunch, Richard Baxell read from his exemplary oral history of the British Battalion, Unlikely Warriors, celebrating its paperback launch. I urge you to buy it now, if you haven’t already.

Jane Rogoyska then introduced those iconic Spanish Civil War photographers André Friedman and Gerda Pohorylle. At least that was their original names before, as anti-fascist refugees in Paris, they began to work collectively under the invented persona of Robert Capa. In Spain, Friedman took over this name completely and Pohorylle began to forge an independent but tragically short-lived career as Gerda Taro. She was killed at the Battle of Brunete, having stayed for a few days longer than planned in the hope of capturing a few final shots. The sensational reappearance in 2007 of three boxes of missing negatives taken by both photographers, and also David Seymour (Chim) have been the subject of a recent exhibition and documentary The Mexican Suitcase. Taro’s funeral in Paris was attended by 10,000 mourners but until relatively recently she was almost completely forgotten. I’ll be visiting Père Lachaise cemetery for other reasons next week, so I shall definitely be seeking out her grave, which bears a sculpture by Giacometti.

Jane Rogoyska then introduced those iconic Spanish Civil War photographers André Friedman and Gerda Pohorylle. At least that was their original names before, as anti-fascist refugees in Paris, they began to work collectively under the invented persona of Robert Capa. In Spain, Friedman took over this name completely and Pohorylle began to forge an independent but tragically short-lived career as Gerda Taro. She was killed at the Battle of Brunete, having stayed for a few days longer than planned in the hope of capturing a few final shots. The sensational reappearance in 2007 of three boxes of missing negatives taken by both photographers, and also David Seymour (Chim) have been the subject of a recent exhibition and documentary The Mexican Suitcase. Taro’s funeral in Paris was attended by 10,000 mourners but until relatively recently she was almost completely forgotten. I’ll be visiting Père Lachaise cemetery for other reasons next week, so I shall definitely be seeking out her grave, which bears a sculpture by Giacometti.

Finally, Valentine Cunningham, who has written widely on the

literature of the 30s, and the Spanish Civil War in particular, addressed the subject of aestheticising tragedy. An almost exhaustive list of writers and artists who took up the Spanish cause led into to a thought-provoking discussion of two dominating tendencies in its literature: an ekphrastic urge (much of the poetry is not about places, people or events but about photographs of them) and personal testimony. Despite Margot Heinemann’s moving expression of her desire to ‘grieve in a new way for new losses’ in her poem about her dead lover John Cornford, one of the oldest modes of all is the most persistent in SCW writings: elegy. Through elegiac texts, films and photographs, the dead live on in our memories.

literature of the 30s, and the Spanish Civil War in particular, addressed the subject of aestheticising tragedy. An almost exhaustive list of writers and artists who took up the Spanish cause led into to a thought-provoking discussion of two dominating tendencies in its literature: an ekphrastic urge (much of the poetry is not about places, people or events but about photographs of them) and personal testimony. Despite Margot Heinemann’s moving expression of her desire to ‘grieve in a new way for new losses’ in her poem about her dead lover John Cornford, one of the oldest modes of all is the most persistent in SCW writings: elegy. Through elegiac texts, films and photographs, the dead live on in our memories.

Thanks to the International Brigade Memorial Trust for organising this event. Visit their website to join and keep informed about other Spanish Civil War related events, including visits to Spain.

February 8, 2014

National Libraries Day

Today’s the day to show your love for all the libraries in the country, and celebrate with millions of other library lovers. You can read my guest blog for NLD2014 here and find out more about events near you and get involved here. So here’s to libraries everywhere! Can you imagine life without them?

January 26, 2014

Authors Take Sides

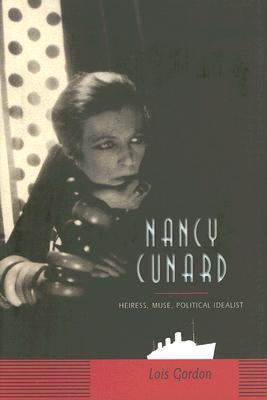

Who is this glorious woman?

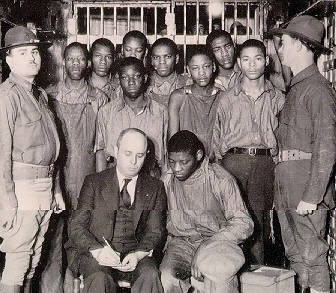

If you saw the recent production of The Scottsboro Boys at the Young Vic in London you’ll be interested in her involvement in the campaigns on both sides of the Atlantic to free these nine young black men falsely charged with raping two white women on a freight train in Alabama in 1931. The dazzlingly beautiful, taboo-breaking daughter of a British shipping magnate, Nancy Cunard started her career as a journalist with the Associated Negro Press (ANP), but she was also a poet, political activist and a publisher. Charismatic and idealistic, she clearly had a genius for motivating the radical intellectual circles, black and white, in which she largely moved.

Her mother – a close friend of Oswald Mosley – disinherited her fairly speedily in 1931. Over the next few years Nancy Cunard took part in the hunger marches in Britain, raised funds and agitated on behalf of the Scotsboro Boys, published a ground-breaking anthology of essays on black history (Negro ,1934), founded the publishing house which first took on Samuel Beckett, and reported on the Ethiopian crisis for the ANP alongside fellow journalists Langston Hughes, Paul Robeson and Richard Wright.

The Scotsboro Boys in 1932, with their lawyer Samuel Leibowitz (source: Wiki Commons)

Unsurprisingly, as soon as the Spanish Civil War broke out, Nancy Cunard headed for Barcelona. ‘Spain took hold of me entirely’ she wrote later. According to her biographer Lois Gordon, Spain was her greatest cause: she ‘went to the fronts to write eyewitness reports, help carry the wounded to safety, and feed the hungry; after Franco’s victory, now the Manchester Guardian’s sole eyewitness reporter, she walked with the refugees as they trudged to Perpignan and to their “holding centres” – really French concentration camps. With Hitler’s planes bombing everyone on the road, Nancy became accustomed to running for her life….Nancy remained a one-person army for years to come.’ [Interview with Gordon, author of Nancy Cunard: Heiress, Muse, and Political Idealist, 2007]

In Madrid, at the house of Pablo Neruda, Cunard met Spanish Republican writers such as Rafael Alberti, Federico Garcia Lorca and Miguel Hernandez, and it was Neruda who encouraged in her plan to publish the pamphlet series The Poets of the World Defend the Spanish People, with poems in English, Spanish and French, including Auden’s controversial ‘Spain’. This led to a new project, Authors Take Sides on the Spanish War (London: Left Review, 1937), for which she sent a questionnaire to the poets of the British Isles, canvassing their opinions on the war, and the policy of non-intervention.

‘Are you for, or against, the legal Government and the People of Republican Spain? Are you for, or against, Franco and Fascism?

For it is impossible any longer to take no side.’

You can read the entire publication here, and it’s well worth it. The difference in tone between the responses, for example, of Marcus Garvey and Geoffrey Grigson, is fascinating. One makes reference to ‘the cult of organised murder’, the other to ‘potted shrimps in the club…reading the Manchester Guardian…holding hands in the cinema.’ You’ll also find what Eric Linklater of Emil and the Detectives fame had to say on the subject, as well as the words of two other writers who had a big influence on me in my youth, Antonia White (Frost in May) and Rosamund Lehmann (Invitation to the Waltz).

I also thoroughly recommend this article by Eric Hobsbawm on the subject, written for The Guardian in 2007. ‘Of the British writers asked, five (Waugh, Eleanor Smith and Edmund Blunden among them) favoured the Nationalists, 16 were neutral (including Eliot, Charles Morgan, Pound, Alec Waugh, Sean O’Faolain, HG Wells and Vita Sackville-West) and 106 were for the republic, many of them passionately…Writers supported Spain not only with money, speech and signatures, but they wrote about it, as Hemingway, Malraux, Bernanos and virtually all the notable contemporary young British poets – Auden, Spender, Day Lewis, MacNeice – did. Spain was the experience that was central to their lives between 1936 and 1939, even if they later kept it out of sight.’

It took decades to shake off the British notion of the Spanish Civil War as solely a poets’ war, and recognise the fact that the vast majority of International Brigade volunteers came from very ordinary, working-class backgrounds. Artists and writers are back in the foreground this year at the International Brigade Memorial Trust’s annual Len Crome ‘Lecture’ on March 1st at the Manchester Conference Centre: Taking Sides: Artists and Writers in the Spanish Civil War. The programme is extremely promising, with contributions from Jane Rogoyska on the photographers Gerda Taro and Robert Capa, Paul Preston talking about foreign correspondents, Carmen Herrero discussing the representation of the International Brigades in Spanish Cinema and Carl-Henryk Bjerstrom presenting his research on arts and education in Republican Spain. I’m very much looking forward to it.

January 14, 2014

Ravilious

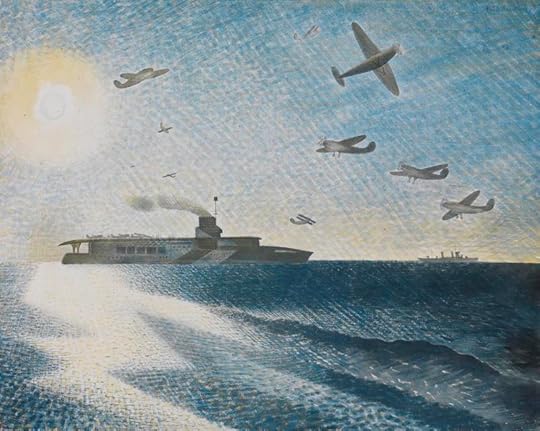

Ravilious in Pictures: The War Paintings by James Russell (The Mainstone Press) – one of the most thoughtful and appropriate Christmas presents I received last month – has many resonances for That Burning Summer. Eric Ravilious (1903-1942) was probably the best known of the three British Official War Artists who were killed during the Second World War, despite the unofficial hope on the part of Kenneth Clark, who created the scheme, that it would preserve the lives of Britain’s best artists. (Thomas Hennell disappeared in Java in 1945; Albert Richards, who fought as well as painted, was blown up by an enemy mine in Belgium in March the same year.) The picture above, HMS Ark Royal in Action, 1940, [© IWM (Art.IWM ART LD 284)] is a watercolour made on June 9th from the deck of HMS Highlander and it shows the ship’s anti-aircraft guns at full-blast in the last moments of the Allied withdrawal from Narvik after the fall of France.

In July 1940, the National Gallery mounted its first exhibition of war art, and Ravilious was embarrassed by quite how many of the paintings were by him. He’d taken up the invitation to become an Official War Artist as soon as he was offered it in December 1939, after an autumn spent volunteering with the Observer Corps, watching for enemy aircraft from a post on the top of Sudbury Hill, near his home: “We wear lifeboatmen’s outfits against the weather and tin hats for show. It is like a Boy’s Own Paper story, what with spies and passwords and all manner of nonsense.” (p. 8)

This sense of unreality – the idea almost of playing at soldiers – was remarkably widespread in Britain in that first year of the war, and something I tried hard to capture in That Burning Summer. Equally strong was a sense of growing threat to a particular, pastoral kind of Englishness, a vision of England which Ravilious arguably helped to create. It comes across strongly in the book he illustrated for the Curwen Press book, The Story of the High Street.

In a painting called ‘Observers’ Post’ Ravilious conveys the incongruity of sandbags, duckboards and telephone wires appearing suddenly beside rustic wooden fences and reassuring hedgerows, and under blue skies. His sandbags have a plumped up, pillow-like feel to them, and glow quietly in the last rays of the sun. Another watercolour of 1940, showing Barrage Balloons Outside a British Port is darker, greyer, and the two lone figures at the end of a quay are leaning forward with a greater sense of urgency, but there is a similar tension between the bravely comic whale-shaped monsters (whose accidental escapes Ravilious had frequently sighted from his Observers’ Post) and the reassuringly straight lines of harbour buildings and railings. Meanwhile, the extravagant curve of the quay in the foreground suggests that the land itself is on the verge of becoming as stormy as the sea and sky beyond.

Balloons, ships and aircraft are often given as much, if not more, character than the few people depicted in Ravilious’ war pictures. They come across as plucky creatures. Here, in HMS Glorious in the Arctic, 1940, Hawker Hurricanes and Gloster Gladiators circle the aircraft carrier as they prepare to land on her deck, before leaving Norway.

© IWM (Art.IWM ART LD 283)

© IWM (Art.IWM ART LD 1712)

In the course of his posting to the Royal Navy, Ravilious discovered his fascination with flight. At the Royal Naval Air Station in Dundee he was enthralled by the eccentricities of a lumbering amphibious biplane called a Supermarine Walrus, which could be launched by catapult from a warship, and became very effective in air-sea rescue operations. ’I spend my time drawing seaplanes and now and again they take me up…I do very much enjoy drawing these queer flying machines…what I like about them is that they are comic things with a strong personality like a duck…You put your head out of the window and it is no more windy than a train.’ (p.36)

He soon graduated from the co-pilot’s seat to the rear-gunner’s position, which offered a much better view – along with some slightly alarming duties involving hatches and such: ‘How trusting they are!’

When Ravilious began his next War Artist contract, it was with the RAF. ‘These planes and pilots are the best things I have come across since this job began. They are sweet and have no nonsense (naval traditional nonsense and animal pride).’ (p38) The luminosity of Ravilious’ watercolour technique was perfectly suited to conveying the peculiar joys of simply being airborne. Over the course of the summer of 1942, he flew regularly in Tiger Moths from a modest airbase in Hertfordshire, at Sawbridgeworth, where the runway was made of coconut matting and living conditions were equally basic. Yet, as it wrote home: ”It was more lovely than words can say flying over the moors and the coast today in an open plane, just floating on great curly clouds and perfectly still and cool . . .” (p. 44)

© IWM (Art.IWM ART LD 2123)

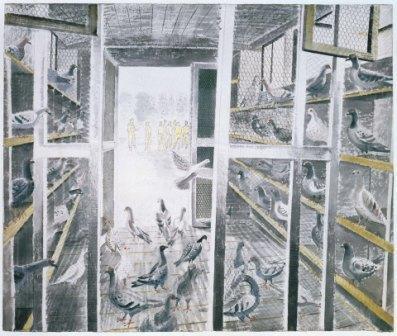

One of my favourite pictures in this book took me back to some of my early research for That Burning Summer. From a long and fascinating conversation with Edward Carpenter, local historian and author of Romney Marsh at War, I confess I stole his story of rescuing a lost homing pigeon, for which – if I remember rightly – he was given a medal. During World War Two, thirty-two pigeons were awarded medals themselves, as James Russell writes in the short essay accompanying this atmospheric watercolour of Corporal Stediford’s Mobile Pigeon Loft. Thousands of lives were saved by birds flying home bearing the co-ordinates of a crash site, and every bomber crew carried one. The pigeons here are full of life and character, with their bright red eyes and distinctive markings. By contrast, the distant group of soldiers who can just be seen through the open doorway are barely there at all. Like the ghostly figures in the painting Morning on the Tarmac, in which sailors or airmen who aren’t even given the solidity of the reflections granted to the aircraft, these men seem on the point of vanishing altogether. Ravilious disappeared himself in Norway on 2nd September. His own plane never returned from a mission to search for survivors after a previous aircraft had gone missing.

From ‘Ravilious in Pictures: The War Paintings’ by James Russell.

Next on the Ravilious reading list must surely be Alan Powers’ new biography, which sounds extremely promising. Alan Power will be giving a talk on Ravilious at the Victoria and Albert Museum next month. Find out more about the artist and other books in this Mainstone Press series on James Russell’s website.

December 22, 2013

Wartime Christmas

Today’s war-themed window in the Carnegie 2014 Advent Calendar by We Sat Down is my inspiration for this final post of the year. Christmas in wartime tends to be peculiarly poignant – so often dark with separation, and haunted by the ghosts of past celebrations. Ritual is disrupted, and hope can seem fragile. Both That Burning Summer and A World Between Us include not scenes, but memories of Christmas.

Confused and ill, hiding in an isolated church in Kent, Henryk half-believes himself back in Beirut. In 1939 a number of Polish airmen spent their first Christmas away from home trapped on the boat that had brought them from Bulgaria, unable to embark:

Nothing to eat for hours and hours, nothing to do but sing, and drink. Someone had a mouth organ. Zygi. Yes, that’s right, it was Zygi who played the mouth organ, really quite well, considering. Where was Zygi now? He played tangos and then the Funeral March. And of course Boże, coś Polskę. Polskę, Polskę ah Polskę. Home in their hearts and head.

But nobody could actually speak of home. They wept. They drank some more. Such longing. Henryk felt it again now. He swallowed the spit pooling in his mouth, and remembered thinking of the girls as they walked around the Christmas tree in their best dresses, just as they had the year before and the year before that. Every year the same. Could it possibly be true again? He didn’t know then, not in Beirut. He could still believe it was possible.

(That Burning Summer, p. 145)

Beirut, 1940s, Copyright Library of Congress

The idea of Christmas plays a very different role in A World Between Us. Re-united with Nat at last, drinking sherry in a bar in besieged Madrid, Felix is reminded of Christmas at home, and what she’s missed. Christmas is a measurement of how far she’s come.

‘”Makes you homesick, does it?” Nat was sympathetic.

“The opposite…It makes me realise what I’ve escaped. The annual sherry ritual. So predictable. So irritating. So much fuss about nothing. Ghastly. In fact, I don’t even know why I’m talking about it. Of all things…”

“I want to hear.” He leaned forward.

“Oh, don’t get the wrong idea. It’s not a proper ritual, not religious or anything. It’s just that’s when we always drink it. On Christmas Day, once a year. The sherry bottle comes out of the corner cupboard, after church and before lunch. Harvey’s Bristol Cream. It’s funny how it never seems to run out.”

Six cut-glass sherry glasses, polished so carefully by her pedantic and controlling brother, assume a weight of significance which Nat finds hard to understand. ‘”I don’t know why I thought of it,”‘ says Felix, eventually. ‘”I suppose because it all seems so irrelevant now. All that worrying about things.”‘ (A World Between Us, pp130-132)

During the Spanish Civil War, the most memorable Christmas for many International Brigaders was in 1937. It was the year the Republicans ‘got’ Teruel for Christmas, recovering the town from Nationalist forces in the middle of the worst winter Spain had seen for twenty years. ”Teruel is Christmas present enough,” wrote the American poet and ambulance driver James Neugass, author of the most vivid and moving memoir of the Spanish Civil War I have ever read, War is Beautiful.

Here is Neugass’ description of Christmas morning at Alcorisa:

The radio in the ward . . . purrs peace across the Western hemisphere. Organ music from half the great cathedrals of Europe rolls over the coughing figures on the beds. I am very glad for the cold which seems to have permanently crippled my sense of smell. From Finland to Greece, Church dignitaries, ministers of Education, senators and cabinet ministers sob their two cents’ worth of heavenly peace over the air, with the piety of whores on a holiday.

Nevertheless, that stained-glass purplish Christmas feeling is inescapable. It is difficult not to feel sorry for yourself. All of the world is calm and pure on December 25th.

The dance last night at Andorra was no riot. I cannot boast of a hangover. The medical alcohol ran short.

That afternoon, the ward was visited by Len Crome (probably now a familiar name to readers of this blog):

Commandante Crome (real nom de guerre)…has just addressed us. C. is the son of White Russians, educated in Scotland. His riding boots are the only perfectly polished leather I have seen in Spain. Some of us think that C. is a Prince or a Duke. He could step into the leading role of a Hollywood Zenda romance. Why has he come to Spain?

The speech Neugass recalls gives a good taste of Crome’s style of leadership.

“You must remember that the infantry think as much of the Medical Corps as they do of their helmet. You are their shield. You must also remember that each of you is personally responsible to the anti-fascist men and women of the world who sent you here. They are your commanders. We officers are here to organise rather than to command. With the discipline you shall impose on yourselves, we shall win.

“Are there questions?”

(War is Beautiful, pp 78-81)

November 30, 2013

Competition: The History Girls

This week there’s a chance to win a copy of That Burning Summer thanks to the The History Girls - if you already don’t know this consistently thought-provoking blog, I highly recommend exploring it. Find out here how mooching for years on Romney Marsh inspired me to writeThat Burning Summer, and then enter the competition here – you’ve got until December 7th to win one of five books. The question relates to the church in which Peggy hides Henryk…my favourite church in all the world, St Thomas Becket, Fairfield, Kent.

This week there’s a chance to win a copy of That Burning Summer thanks to the The History Girls - if you already don’t know this consistently thought-provoking blog, I highly recommend exploring it. Find out here how mooching for years on Romney Marsh inspired me to writeThat Burning Summer, and then enter the competition here – you’ve got until December 7th to win one of five books. The question relates to the church in which Peggy hides Henryk…my favourite church in all the world, St Thomas Becket, Fairfield, Kent.