Lydia Syson's Blog, page 4

September 5, 2015

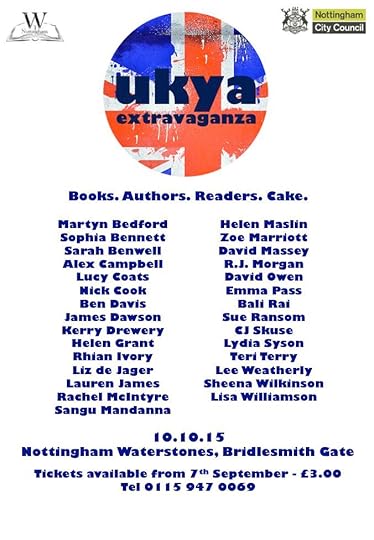

UKYA Extravaganza

I’m not sure if it sounds more like a circus or a speed-dating event for authors and readers, but I am absolutely certain that the second ever UKYA Extravaganza on October 2015 is going to be a sell out. If you live anywhere near Nottingham and want to come, do book as soon as you can. These events are all about bringing YA authors to fans outside London – read here about the first one, which took place in Birmingham in February this year – and were dreamt up by the indefatigable fellow authors Kerry Drewery (A Brighter Fear and A Dream of Lights) and Emma Pass (Acid, The Fearless). Everyone can join in during the run up thanks to the UKYAX Blog Tour. I’m so pleased to be paired up with award-winning Michelle ‘Chelley’ Toy (UKYABA Champion Newcomer 2015) of TALES OF YESTERDAY (very appropriately!) and we’re putting our heads together for a surprise on September 18th. Find out which authors will be waiting to meet you in Nottingham below, and buy tickets from Waterstones in Nottingham (or book by phone) tomorrow from 9 o’clock onwards….

I’m not sure if it sounds more like a circus or a speed-dating event for authors and readers, but I am absolutely certain that the second ever UKYA Extravaganza on October 2015 is going to be a sell out. If you live anywhere near Nottingham and want to come, do book as soon as you can. These events are all about bringing YA authors to fans outside London – read here about the first one, which took place in Birmingham in February this year – and were dreamt up by the indefatigable fellow authors Kerry Drewery (A Brighter Fear and A Dream of Lights) and Emma Pass (Acid, The Fearless). Everyone can join in during the run up thanks to the UKYAX Blog Tour. I’m so pleased to be paired up with award-winning Michelle ‘Chelley’ Toy (UKYABA Champion Newcomer 2015) of TALES OF YESTERDAY (very appropriately!) and we’re putting our heads together for a surprise on September 18th. Find out which authors will be waiting to meet you in Nottingham below, and buy tickets from Waterstones in Nottingham (or book by phone) tomorrow from 9 o’clock onwards….

July 6, 2015

In the footsteps of Communards

What happened to the revolutionaries who managed to escape Paris after the bloody fall of the Commune? Over three thousand ended up in London, men, women and children too. I’ve blogged about following the trail of some of those exiles today at The History Girls. Follow the link to find out more about what I found, including ’bloody foreigners’, police spies, chemistry lessons and Louise Michel’s International School in Fitzrovia.

June 23, 2015

Coming up…

27 June 2015 (For info): Anarchism & Education: the history of Louise Michel and her international school in London 4 July 2015: International Brigade annual memorial event 1 – 2pm Jubilee Gdns, London

WELCOME

… you’ve reached the website of Lydia Syson, author of LIBERTY’S FIRE, THAT BURNING SUMMER, A WORLD BETWEEN US, & the biography DOCTOR OF LOVE: DR JAMES GRAHAM AND HIS CELESTIAL BED. Do click on ‘Reviews‘ to discover what other readers have thought of all these books, and then scroll down to find out more about the history behind the novels. For those on larger screens, on which this website works much better, apologies for any repetition. You’ll find the latest blogpost just below.

… you’ve reached the website of Lydia Syson, author of LIBERTY’S FIRE, THAT BURNING SUMMER, A WORLD BETWEEN US, & the biography DOCTOR OF LOVE: DR JAMES GRAHAM AND HIS CELESTIAL BED. Do click on ‘Reviews‘ to discover what other readers have thought of all these books, and then scroll down to find out more about the history behind the novels. For those on larger screens, on which this website works much better, apologies for any repetition. You’ll find the latest blogpost just below.

Find out about school visits and other author events here

Buy LIBERTY’S FIRE here

Buy THAT BURNING SUMMER here

Buy A WORLD BETWEEN US here

Buy DOCTOR OF LOVE here

‘The Red Virgin’

There is a character in Liberty’s Fire who is not named, but can be easily identified as Louise Michel, the best known of a number of impressive citoyennes featured in this blog post last month. Michel was one of many Communards who took refuge in London, and Fitzrovia in particular, to escape political repression in France in the aftermath of the Commune – even after the ‘Amnesty’ – and it was here that she met my great-great grandmother, N.F.Dryhurst, a member of the English Anarchist group.

Last Saturday I had the very great pleasure of leading a well-attended walk for the Fitzrovia Festival, which is organised annually by a very active and welcoming Fitzrovia Neighbourhood Centre, (this year celebrating forty years of community activity) during which we explored the London lives of a number of Communards ‘after the fall’. I’ll be writing that up in full for The History Girls next month. [We are all still loudly cheering today after Tanya Landman's wonderful Carnegie triumph with her most compelling novel Buffalo Soldiers, and I do urge you to read her latest HG post as well as the novel.] In the meantime, here’s are some views of Louise Michel in later life. The first is by the war correspondent Henry Nevinson, and comes from his memoir Fire of Life (1935):

Last Saturday I had the very great pleasure of leading a well-attended walk for the Fitzrovia Festival, which is organised annually by a very active and welcoming Fitzrovia Neighbourhood Centre, (this year celebrating forty years of community activity) during which we explored the London lives of a number of Communards ‘after the fall’. I’ll be writing that up in full for The History Girls next month. [We are all still loudly cheering today after Tanya Landman's wonderful Carnegie triumph with her most compelling novel Buffalo Soldiers, and I do urge you to read her latest HG post as well as the novel.] In the meantime, here’s are some views of Louise Michel in later life. The first is by the war correspondent Henry Nevinson, and comes from his memoir Fire of Life (1935):

‘”The Red Virgin” was conspicuous at nearly all the [Anarchist] meetings – conspicuous in ancient black, always worn to commemorate her fellow Communards pitilessly slaughtered in Paris (1871) to glut the bloodthirsty of the bourgeoisie, who, crowding around the slaughter-house with jeers and laughter, stood to witness the executions in mass. Old black bonnet, shaped like the Salvation Army bonnet and flung anyhow on top of the wild and copious grey hair; old black shawl; long black dress; and, making one forget dress and age and all, the think white face, lined with mingled enthusiasm and humour; prominent nose and receding chin, high and receding forehead, and under it keen grey eyes, eagerly peering out upon the world with rage, humorous pity, and gentleness strangely combined. She always spoke in French, her quiet and monotonous voice just rising and falling, sweet and low as the summer sea. ”Ne cadencez pas, monsieur, ne cadencez pas!” she used constantly to say to me in her vain attempts to teach me her beautiful language; but her own cadence was regular and inevitable as the waves. ”I am growing old,” she said at the beginning of one of her greatest speeches, “and as I grow old I learn to have patience.”‘ (p. 52)

(‘Ne cadencez pas‘ is probably best translated as ‘not so sing-song’ or ‘don’t make it rhythmical’.)

Henry Nevinson

Nevinson is coy here about his introduction to the English Anarchist circle, referring only to ‘a deep and lasting friendship with a very remarkable member of the Anarchist group’, but you can read the full story of Nevinson’s life, including his relationship with N.F.Dryhust and other anarchists, in Angela John’s wonderful biography War, Journalism and the Shaping of the Twentieth Century (2006). This London Fictions article about his East End life and short story collection Neighbours of Ours gives a good clue as to why he came to be teaching ‘drill’ of all things at Michel’s International School in Fitzroy Street. In Fire of Life, Nevinson is a little more revealing about his feelings for Dryhurst when he describes the staff of reviewers he used during his time as literary editor of The Daily Chronicle: ‘For Irish history and literature, as well as for Shakespearean times, there was Mrs N.F.Dryhurst, always bringing with her the wit of Ireland, the kindling inspiration, the flaming wrath, and a sarcasm like the lick of a lioness’s tongue.’ (p.85.)

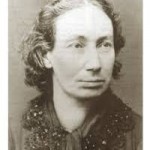

Nannie (N.F.) Dryhurst

As for the Red Virgin, educationalist, fellow Fabian and nursery school pioneer Margaret McMillan, whose sister Rachel also volunteered at Michel’s school, offers another view of the former communarde. Like so many of her contemporaries, McMillan had clearly fallen sway to the popular vogue for physiognomy, and found Michel’s physical appearance somewhat disconcerting:

‘She had taken off her hat and the shape of her head was anything but reassuring. Why, then, did her features, her eyes, her voice, contradict its testimony? Her mild, dark yes, full of pity and veiled fire, might have belonged to Francis d’Assisi, and she had the profile of Savonarola, but the head was alarmingly narrow at the top. Like that of another prominent Anarchist, it had no arch, but ended like the unfinished roof of a building. The whole physiognomy, despite its expression of strange forms of pity, was unfinished. This profile made you dream, when you got over your first alarm, of the sub-structure of a new and fine humanity. All the same it was not reassuring. The beholder felt himself exposed to all the storms and terrors of temperament by reason of the unfinished roof…Very often it was hard to know whether she was the forerunner of a great race, or a reversion to early type. She, for her part, had no doubt about our present civilisation, its leaders and followers.

“Primates,” she said, “Primates tous – who advance a little and then become corrupt.”‘

Louise Michel

June 6, 2015

Meet the archivist…at the Marx Memorial Library

This interview first appeared on The History Girls blogsite on June 6th 2015:

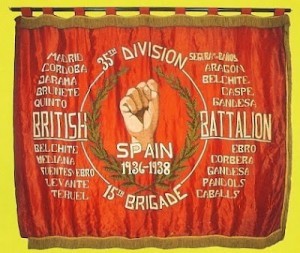

In April I wrote about the Conscience and Conflict exhibition of British artists’ responses to the Spanish Civil War, which closes tomorrow. If you’ve been lucky enough to see it, either in Chichester or Newcastle, you may have noticed some wonderful loans from the Marx Memorial Library, home of the British International Brigade archives. This rich and varied collection is just one reason to visit the Library, which now offers twice-weekly guided tours. I’ve been talking to the MML’s new(ish) archivist and development officer, Meirian Jump, pictured here at work in the reading room in front of a mural by Viscount Hastings, painted in 1934.

What exactly is the Marx Memorial Library, and what is it that makes this ‘hidden gem’ so special?

The Library has a fascinating history and has been at the heart of the British labour movement for over 80 years. It was founded in 1933 by a group of socialists, communists and labour movement activists in response to the Nazi book burning in Germany, and as a memorial to mark 50 years since Marx’s death. It’s a registered educational charity and independent library which covers all aspects of the science of Marxism, the history of socialism and the working class movement.

The Library has a fascinating history and has been at the heart of the British labour movement for over 80 years. It was founded in 1933 by a group of socialists, communists and labour movement activists in response to the Nazi book burning in Germany, and as a memorial to mark 50 years since Marx’s death. It’s a registered educational charity and independent library which covers all aspects of the science of Marxism, the history of socialism and the working class movement.Marx House itself is a beautiful mid-eighteenth century Grade II listed building looking over historic Clerkenwell Green, where the London May Day rally has gathered since 1890. [Note: Read an account of Clerkenwell's radical history written when the library first opened here.] It was originally built as a charity school for the children of welsh artisans residing in the area. It has a history rooted in London’s radical tradition; the International Working Men’s Association met here, it was home to socialist printing house Twentieth Century Press and Lenin worked here in exile.

Not only does the building itself tell this fascinating story, but it’s home to unique collections documenting the struggles of working people spanning centuries. We hold a library of over 45,000 volumes, but also archival collections on the Spanish Civil War, the local print unions and radical publishing, to name but a few. [Find out more here.]

You must have uncovered new surprises every week when you started work here – what, for you, are the highlights of the collections? And what do newcomers get most excited about on the new guided tours?

Yes! I have been working here for just under 6 months. One of the central aspects of my role is to ensure that we know exactly what we have in the building. Just after I started over Christmas I spent several days in the library digging around in the basement getting a handle on the collections. As you can imagine, this was a lot of fun.

It is difficult to pick highlights or favourites, and, as you mention, we are always uncovering new things. I personally love browsing the complete run of Daily Worker / Morning Star newspapers we hold. Fascinating stories of strikes, demonstrations and struggles can be traced through their front pages. We are also carrying out a complete inventory of our poster collection. We have over 3,000, and many of them are very visuall striking, as well as being illuminating historical sources.

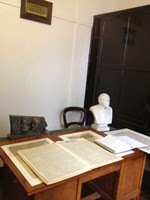

Visitors often get excited about the posters, and also about the Lenin room, which is a real highlight of our guided tours. Members of the public can visit the tiny office where Lenin worked in exile editing ‘The Spark’, a Bolshevik newspaper. It is very atmospheric.

Archivists and librarians are the unsung heroines and heroes of anyone who writes about history, whether fiction or non-fiction, for children, adults or inbetweeners. What drew you to the profession, and particularly to your role at the MML?

I’ve always enjoyed research and working in libraries and archives. I also love working with people, and helping people, which – despite the stereotype – is a key part of any archivists work!

Working as the Archivist at the Marx Memorial Library is a dream come true for me. I first studied here as an undergraduate looking at the Aid Spain Movement and the British International Brigades, and was immediately taken by the Library’s unique atmosphere and phenomenal collections on twentieth-century history. It was a personal family connection that first got me into this area of research. My grandfather Jimmy Jump was one of the 2,500 people who volunteered to fight against Franco’s forces in Spain when the civil war broke out in 1936. My grandmother was an exile from the civil war and came over to Britain with the 4,000 Basque refugee children in 1937. As you can imagine, being able to play an active part in making the archives of the International Brigaders held at the library available to wider audiences is incredibly rewarding.

Next year sees the 80th anniversary of the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War. Can you tell us how the MML will mark this?

The upcoming anniversary is a great excuse to ‘launch’ our Spanish collection to broader audiences. We have some exciting plans in the pipeline.

We’ve applied for funding to employ a project archivist who will (fingers crossed) ensure that the collection is professionally catalogued in full. The catalogue will be made available on our website. This should make an enormous difference to researchers who will be able to search for people, places and events in the collection.

We’re also planning on digitizing some components of the collection. We have wonderful visual material in the collection including photographs, posters and pamphlets. We plan on making these available on our website, and using them in an education pack aimed at school children. We believe it is really important that the Spanish Civil War and the story of the Brigaders form part of the syllabus of secondary school pupils.

I don’t want to give too much away, but we also anticipate putting on a series of cultural and academic events to mark the formation of the International Brigades, in partnership with the International Brigade Memorial Trust.

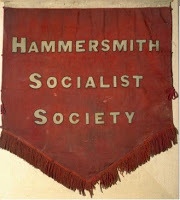

As an archivist, what are your feelings about the gains and losses

of digitization? Is ‘aura’ at the back of your mind when you’re handling the original Hammersmith Socialist Society banner for example, back from the recent William Morris exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery, or do practical concerns about conservation and damage override your emotional response to the artefacts in your care?

I think digitization plays a very important role in ensuring that information from archival collections is more widely available online, and in ensuring the long term preservation of collections and items that might be damaged if put out on display or made available to researchers in the reading room.

I think digitization plays a very important role in ensuring that information from archival collections is more widely available online, and in ensuring the long term preservation of collections and items that might be damaged if put out on display or made available to researchers in the reading room.However, its importance can be overplayed. People often have an idea that if archives are ‘digitised’ problems of preservation and access are ‘solved’. Digital files also need to be properly stored on a server, backed up, and indexed or catalogued so that they can be found again.

Sometimes only the original will do! – the type of paper,

the detail the camera won’t pick up on, evidence of how the item was used before and – as you mention – the hard-to-define feel of the artefact. I particularly found this with a letter written by Eleanor Marx that we have in our collection. It is currently out with conservators and soon to be put on display at the Library, alongside her portrait. Being able to read that very letter, hand-written by Eleanor in the building where she herself spoke feels very special.

the detail the camera won’t pick up on, evidence of how the item was used before and – as you mention – the hard-to-define feel of the artefact. I particularly found this with a letter written by Eleanor Marx that we have in our collection. It is currently out with conservators and soon to be put on display at the Library, alongside her portrait. Being able to read that very letter, hand-written by Eleanor in the building where she herself spoke feels very special.Even for those ‘in the know’, the Marx Memorial Library hasn’t always been the easiest place to penetrate – what’s now changed and what are your hopes for the future? Since the last election, there’s been a lot of talk about politics being far less ‘tribal’ than it used to be. Is that something the MML can turn to its advantage?

That’s right. My central aim at the Library is to open its doors and to engage with a wider audience. There really is no point in having all these phenomenal resources that tell such an important story about our history, if nobody knows they’re here and people aren’t using them.

A lot has changed, but there’s still a way to go. It is now very easy to join the library, we are open four days a week, we have launched guided tours of the building twice a week on Tuesdays and Thursdays. We are also looking into getting a new sign put up so we are a bit easier to find! More generally we are hoping to put the library on the map with events like our May Day open day and our upcoming exhibition on Socialist Opposition to the First World War.

I think you’re right. We have an important role in engaging with people across the spectrum including people who weren’t brought up with a knowledge of this history and who wouldn’t necessarily think of themselves as ‘Marxists’. You can see this in our education programme. We are putting on ‘entry level’ classes and are covering a much broader range of topics including socialist art and historic memory. We are revisiting the displays in the library too. We don’t want to assume knowledge and want to be as inclusive as possible.

And if people want to consult the archives or take a guided tour…?

The reading room is open to researchers Monday-Thursday 12-4; the guided tours take place Tuesdays and Thursdays at 1pm. Information on our classes can be found on our website or by emailing admin@mml.xyz. We also have special events coming up including two fundraising theatre performances, panel discussions and book launches.

Thank you, Meirian Jump!

And next month on 4th July between 12.30 and 2 pm you are warmly invited to join the International Brigade Memorial Trust at its annual commemoration of the Spanish Civil War volunteers for liberty from Britain and Ireland at the Jubilee Gardens on London’s South Bank. Full details on the IBMT website.

May 19, 2015

LIBERTY’S FIRE reviews

A Telegraph ‘best YA book of 2015′: ‘Lydia Syson does another fine job of bringing to life sometimes neglected periods of the past. . .the detail is great. . .’ Martin Chilton, Culture Editor online

‘. . .an inspired setting for this tense, dramatic novel. . . The writing is powerful, the events terrifying.’ The Bookbag

‘this exciting and unflinching novel is a hugely satisfying read – and a fascinating one too.’ Absolutely Dulwich magazine

‘This book is a historical gem…tense, moving and written deeply from the heart…Be inspired and read it.’ Mr Ripley’s Enchanted Books

‘a thrilling, daring love story…Syson’s passionate account of the lives of four youths during those dramatic seventy-two days in 1871 is a riveting yarn. With bullets flying and hearts throbbing, she lucidly portrays the historical context and complications, the high hopes and thwarted aims of the first democratically elected socialist government, and its rapid unravelling.’ Jenny McPhee at Bookslut.

‘shocking and fascinating and just hugely emotional…a roller coaster’ Fluttering Butterflies

‘Liberty’s Fire is perfect for fans of Lydia Syson’s previous novels: she has written another beautifully evocative, fascinating historical epic which had me enthralled from the opening pages.’ We Love This Book

‘a thrilling and passionate plot perfect for the teenager in your life.’ Counterfire

‘a truly extraordinary book. Syson brings this pivotal moment in French history into glorious life…’ The Review Diaries

‘gripping…I got swept away with the characters and the situations they were all in: unrequited life, family, dreaming of a better life..’ The Pewter Wolf

‘Lydia…writes my sort of historical fiction…well-researched with a brilliant attention to detail..all in all a fascinating read.’ The Overflowing Library

‘The characters were so strong and different. I don’t think there was a character I didn’t like! The historical backdrop was really vividly written…a beautiful tale of French rebellion.’ The Whispering of the Pages

May 12, 2015

Blog tour roundup. . .

Liberty’s Fire is now out in the world, and the first reviews have even appeared – you’ll find links to all those online here. Oddly enough, I find that even when a book is printed and published, it’s only when people who’ve read it start to ask me questions that I really begin to know what I think about it. Last week I was on ‘blog tour’, and had the enormous pleasure of talking to fellow author Rebecca Mascull here (look out for Song of the Sea Maid in June), Kirsty at The Overflowing Library here, Michelle at Fluttering Butterflies here, Mr Ripley at Mr Ripley’s Enchanted Books here and Andrew at The Pewter Wolf here. I promise I’ve not repeated myself!

But before you read any of those, please do have a look  at the Authors for Nepal auction which has already raised £10,000 for the organisation First Step Himalayas. There are over a hundred lots left to bid for: signed and dedicated books, ‘your name as a book character’ offers, school author visits, manuscript critiques, mentoring lunches with agents and editors…you’ll find everything here.

at the Authors for Nepal auction which has already raised £10,000 for the organisation First Step Himalayas. There are over a hundred lots left to bid for: signed and dedicated books, ‘your name as a book character’ offers, school author visits, manuscript critiques, mentoring lunches with agents and editors…you’ll find everything here.

Don’t delay – auctions are closing just about every hour at the moment. You’ve got until 20.38 on Thursday 14th May to win a job lot of all four of my books, signed and dedicated (see above) – including a first edition of Doctor of Love: Dr James Graham and his Celestial Bed . You can bid for those here. (And look out for a Radio Scotland documentary on the extraordinary electric doctor next month.) Many thanks to Julia Williams and her team for organising everything so quickly.

May 4, 2015

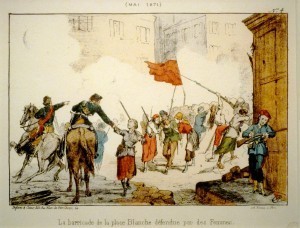

Citoyennes: women of the Paris Commune

The mythical figure of the pétroleuse, hideous or heroic depending on your point of view, has now almost been forgotten. For decades it was the most abiding image of the 1871 Paris Commune, and undoubtedly helped to hide the true history of real women’s involvement in France’s last nineteenth-century revolution. Edith Thomas broke new ground in uncovering this history with Les Petroleuses (1963), angry yet almost apologetic about the need for a corrective to misogynistic accounts of events coming from both sides of the political divide. I’ve written about the ‘women incendiaries’ for The History Girls this month, and you can find out more about the origins of this myth and see a selection of photographs of suspects taken by Eugene Appert at the website of the International Institute of Social History in Amsterdam.

But who were the real citoyennes of Paris,  and why were so many so loyal in their support of the Commune that they were prepared to risk everything for the cause, even to the bitter end? Inevitably, we’ll never know the names of thousands of the women slaughtered during Bloody Week, nor precisely why or how or where they died or were buried. It’s less difficult to see why they became involved. They had ‘nothing to lose and everything to gain’, as Claudine Rey (president of the Association des Amies et Amis de la Commune de Paris 1871) explained in a lecture I attended in Paris in March last year. Working-class Parisiennes lived in truly terrible conditions: a ‘hell of poverty and alcoholism’, in which they faced exploitation of every kind, rising unemployment, derisory and unequal pay, and almost ‘obligatory’ prostitution. Even before the Commune was declared in March 1871, these issues were debated in the political clubs that sprang up as soon as the Second Empire relaxed previously harsh legislation on ‘association’. A new word had to be coined for the women who took to the podium (often a pulpit) to speak: oratrices.

and why were so many so loyal in their support of the Commune that they were prepared to risk everything for the cause, even to the bitter end? Inevitably, we’ll never know the names of thousands of the women slaughtered during Bloody Week, nor precisely why or how or where they died or were buried. It’s less difficult to see why they became involved. They had ‘nothing to lose and everything to gain’, as Claudine Rey (president of the Association des Amies et Amis de la Commune de Paris 1871) explained in a lecture I attended in Paris in March last year. Working-class Parisiennes lived in truly terrible conditions: a ‘hell of poverty and alcoholism’, in which they faced exploitation of every kind, rising unemployment, derisory and unequal pay, and almost ‘obligatory’ prostitution. Even before the Commune was declared in March 1871, these issues were debated in the political clubs that sprang up as soon as the Second Empire relaxed previously harsh legislation on ‘association’. A new word had to be coined for the women who took to the podium (often a pulpit) to speak: oratrices.

Liberty’s Fire was largely inspired by a legend among Communardes, Louise Michel, and the startling discovery that my anarchist great-great-grandmother, Nannie Dryhurst, had worked with her when she lived in London in the 1890s. A truly extraordinary and charismatic revolutionary, the so-called ‘Red Virgin of Montmartre’ relished the opportunities offered by the Commune, and threw herself body and soul into its battles. At her trial, she demanded execution: “Since it seems that every heart that beats for freedom has no right to anything but a little slug of lead, I demand my share. If you let me live, I shall never cease to cry for vengeance.” (Edith Thomas)

Liberty’s Fire was largely inspired by a legend among Communardes, Louise Michel, and the startling discovery that my anarchist great-great-grandmother, Nannie Dryhurst, had worked with her when she lived in London in the 1890s. A truly extraordinary and charismatic revolutionary, the so-called ‘Red Virgin of Montmartre’ relished the opportunities offered by the Commune, and threw herself body and soul into its battles. At her trial, she demanded execution: “Since it seems that every heart that beats for freedom has no right to anything but a little slug of lead, I demand my share. If you let me live, I shall never cease to cry for vengeance.” (Edith Thomas)

Nor did she. Michel was transported to New Caledonia, returning to Europe after the amnesty of 1880. Rather surprisingly, towards the end of her days she lived in East Dulwich, not far from where I now live, and loved animals as passionately as she did the human race. She had a tendency to romanticise her own life, which has been echoed in representations of her ever since. I can’t pretend Liberty’s Fire is any exception! Michel is the only real citoyenne who appears, in fictionalised form, in my novel, and though it was tempting to include many more, the narrative was complicated enough already, and I had to content myself with fleeting references.

Most of the other leading female figures in the Commune are far less well known. None of these very brief summaries of their lives can remotely do justice to these remarkable women, but I hope you’ll be encouraged to find out more about them.

Russian-born Elizabeth Dmitrieff was only twenty  when Marx asked her to go to Paris to report on the Commune for the International Workingmen’s Association. On excellent terms with both Marx and his daughters, she had arrived in London as delegate of a group of Russian revolutionaries she’d met in Geneva. In Paris she helped set up and led the Union des Femmes, energetically recruiting women ‘new to militancy, and who came from a distinctly proletarian background’ (as Thomas put it). They volunteered as nurses and canteen workers, built barricades and fought for equal rights and wages in the workplace, not least for women engaged in making National Guard uniforms, one of the few forms of employment flourishing. Dmitrieff could hardly have been more glamorous, always wearing an elegant black riding habit with a gold-fringed red silk scarf across her chest and a felt hat trimmed with red feathers.

when Marx asked her to go to Paris to report on the Commune for the International Workingmen’s Association. On excellent terms with both Marx and his daughters, she had arrived in London as delegate of a group of Russian revolutionaries she’d met in Geneva. In Paris she helped set up and led the Union des Femmes, energetically recruiting women ‘new to militancy, and who came from a distinctly proletarian background’ (as Thomas put it). They volunteered as nurses and canteen workers, built barricades and fought for equal rights and wages in the workplace, not least for women engaged in making National Guard uniforms, one of the few forms of employment flourishing. Dmitrieff could hardly have been more glamorous, always wearing an elegant black riding habit with a gold-fringed red silk scarf across her chest and a felt hat trimmed with red feathers.

André Léo was a prolific journalist and novelist, likened in her day to George Sand, who was vehement in her opposition to Pierre-Joseph ‘property is theft’ Proudhon’s entrenched sexism. Her real name was Léodile Béra but she used the names of her twin sons as her pseudonym. A early feminist and activist, in 1868 she published a deeply radical ‘Manifesto’ demanding rights for women, which was signed by eighteen other women and attacked the inconsistencies of the Napoleonic code: ’Is a woman an individual? A human being?. . . Why is she obliged to obey laws that she has neither made not consented to? Why is she excluded from the right, recognised by all, of choosing her representatives?. . . the rights of the mother are annihilated by those of her husband. Women’s labour, of equal value, is paid half that of man, and often even this work is denied her.’ (Quoted by Carolyn Eichner in Surmounting the Barricades: Women in the Paris Commune.)

André Léo was a prolific journalist and novelist, likened in her day to George Sand, who was vehement in her opposition to Pierre-Joseph ‘property is theft’ Proudhon’s entrenched sexism. Her real name was Léodile Béra but she used the names of her twin sons as her pseudonym. A early feminist and activist, in 1868 she published a deeply radical ‘Manifesto’ demanding rights for women, which was signed by eighteen other women and attacked the inconsistencies of the Napoleonic code: ’Is a woman an individual? A human being?. . . Why is she obliged to obey laws that she has neither made not consented to? Why is she excluded from the right, recognised by all, of choosing her representatives?. . . the rights of the mother are annihilated by those of her husband. Women’s labour, of equal value, is paid half that of man, and often even this work is denied her.’ (Quoted by Carolyn Eichner in Surmounting the Barricades: Women in the Paris Commune.)

Nathalie Lemel was a co-founder of the Union des Femmes, and another IWA militant, who – like Dmitrieff – criticised the Commune for its failure to promote female suffrage. She left school at the age of 12 to become a bookbinder, and came to Paris from Brittany in search of work after her husband’s alcoholism had bankrupted their business in Quimper, and became a committed strike leader. With Communard Eugene Varlin, she set up a co-operative canteen called La Marmite and was one of the women defending the barricades of Les Batignolles and Place Pigalle, though at her trial she denied being armed: ‘I was satisfied with passing ammunition to the fighters, and giving first aid to the wounded.’ She tried to kill herself after the defeat of the Commune, but was arrested the next day, and deported to New Caledonia. On the voyage out, she met Louise Michel, whom she introduced to anarchism.

Nathalie Lemel was a co-founder of the Union des Femmes, and another IWA militant, who – like Dmitrieff – criticised the Commune for its failure to promote female suffrage. She left school at the age of 12 to become a bookbinder, and came to Paris from Brittany in search of work after her husband’s alcoholism had bankrupted their business in Quimper, and became a committed strike leader. With Communard Eugene Varlin, she set up a co-operative canteen called La Marmite and was one of the women defending the barricades of Les Batignolles and Place Pigalle, though at her trial she denied being armed: ‘I was satisfied with passing ammunition to the fighters, and giving first aid to the wounded.’ She tried to kill herself after the defeat of the Commune, but was arrested the next day, and deported to New Caledonia. On the voyage out, she met Louise Michel, whom she introduced to anarchism.

Paule Mink (Adèle Paulina Mekarska) was born in Clermont-Ferrand to an aristocratic French mother and a Polish father, a count in exile since the unsuccessful 1830 Polish rising. Unlike Léo and Dmitrieff, her path to socialism and feminism was through grass-roots activism and direct democracy: she became well-known as a revolutionary oratrice in the political clubs of Paris in the late 1860s, vehement in her anti-clericism. Alongside Michel, Mink was a member of the Montmartre Committee of Vigilance during the Siege of Paris, and she opened a free school for girls in Saint-Pierre church. She was on a propaganda tour of the provinces during Bloody Week, and managed to escape to Switzerland, where the French police kept tabs on her throughout her exile – only Michel had a bigger dossier.

Marie Ferré, pictured above standing with Louise Michel (centre) and Paule Mink (right), was the sister of Michel’s great friend, the prominent Communard Théophile Ferré. According to Michel’s memoirs, after the fall of the Commune, the Versailles soldiers pressurised their mother into a hysterical fit during which she inadvertently betrayed the whereabouts of her son by threatening to arrest Marie – then bedridden and feverish – in his place. Théophile was found and executed, and his mother died a few weeks later in a psychiatric hospital.

Anna Jaclard – described in 1871 as  a ‘harpy’ and a ‘pétroleuse’ by the secretary of the Russian Embassy in Paris – was born Anna Vassilievna Korvina Krukovskaya had a luxurious childhood on her military father’s Russian estate, and like her mathematician sister Sophie, were swept up in the wind of change blowing through educated Russian families in the 1860s. In St Petersburg, Dostoyevsky published her first, pseudonymous work, A Dream, but she turned down his marriage proposal and used a ‘marriage blanc‘ to escape to Geneva, where she fell in love with the French Blanquist Victor Jaclard, befriended Karl Marx and joined the International. They both went to Paris after the fall of Napoleon III in the early stages of the Franco-Prussian war (September 1870), where Anna became active in the Montmartre Women’s Vigilance Committee. Both Anna and Victor Jaclard were captured during Bloody Week, and she was sentenced to hard labour for life in the New Caledonia penal colony to which Lemel and Michel were exiled, while he received a death sentence. But both managed to escape from prison, arriving via Switzerland in London, where Marx gave them shelter.

a ‘harpy’ and a ‘pétroleuse’ by the secretary of the Russian Embassy in Paris – was born Anna Vassilievna Korvina Krukovskaya had a luxurious childhood on her military father’s Russian estate, and like her mathematician sister Sophie, were swept up in the wind of change blowing through educated Russian families in the 1860s. In St Petersburg, Dostoyevsky published her first, pseudonymous work, A Dream, but she turned down his marriage proposal and used a ‘marriage blanc‘ to escape to Geneva, where she fell in love with the French Blanquist Victor Jaclard, befriended Karl Marx and joined the International. They both went to Paris after the fall of Napoleon III in the early stages of the Franco-Prussian war (September 1870), where Anna became active in the Montmartre Women’s Vigilance Committee. Both Anna and Victor Jaclard were captured during Bloody Week, and she was sentenced to hard labour for life in the New Caledonia penal colony to which Lemel and Michel were exiled, while he received a death sentence. But both managed to escape from prison, arriving via Switzerland in London, where Marx gave them shelter.

Elisabeth Retiffe

Elisabeth Retiffe, cardboard maker, worked as a cantinière and then an ambulancière or nurse during the Commune and was tried as a pétroleuse in September 1871, alongside Leontine Suétens (a laundress-turned-cantinière who was twice wounded) Joséphine-Marguerite Marchais, Lucie Bocquin (day-labourers) and Eulalie Papavoine (a seamstress who followed her partner’s National Guard battalion as an ambulance nurse everywhere he fought). When asked why she had stayed behind at the Charité Hospital when the battalion fled, Papavoine replied: ‘We had dead and wounded men.’ Despite lack of reliable evidence or witnesses – testimony that identified them as active Communardes related to clothing, pillaging, building of barricades, supplying ammunition, gun-carrying, drinking and providing alcohol to others, but not arson -

Léontine Suétens

Retiffe, Suétens and Marchais were sentenced to death, Papavoine to deportation and Bocquin to ten years solitary confinement. The death sentences were later commuted to deportation with hard labour, possibly thanks to the intervention of Victor Hugo. Retiffe is known to have died in the penal colony of Cayenne. Another woman, Marie Alexandrine Leroy, who was in charge of requisitions during the Commune and looked after the orphans of the National Guard, was condemned simply to deportation to New Caledonia.

The last three photographs, reproduced with the kind permission of the Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections, Northwestern University Library, were ’shot’ while the women were in prison by the Eugene Appert, creator of some of the earliest photomontages. More on Appert and his significance coming soon!

Joséphine Marchais

Other Communardes are listed in the preface to Victorine Brocher’s memoir: Maria La Cécilia, Aline Jacquier, Béatrix Excoffon, Blanche Lefèvre, V. Tinayre, Marceline Leloup, Adèle Gauvin, Malvina Poulain, Augustine Chiffon, Deletras, Jarry, JDesfossés, Blin, Poirier, Danguet, Goullé, Smoith, Cailleux, Dupré. These obviously represent just handful of the women involved.

More about Brocher’s book and suggestions for further reading about the women of the Commune can be found here.

April 17, 2015

DOCTOR OF LOVE reviews

“Syson’s enthralling book offers a new portrait of Graham as an authentic innovator… [An] admirable and engaging book.” - The Guardian

“I was entranced by Lydia Syson’s superb volume…

Syson combines a sure grasp of intellectual history with enough awareness of just how much fun her story is. More than that, it shows how the failures and eccentrics of history are often the most intriguing subjects.” - Scotland on Sunday

“Syson pins the iconoclastic Graham like a butterfly on the wider canvas of a lively social history.” - The Times

“Lydia Syson investigates the life of this most progressive of quacks in an engaging dash around the credulous and curious world of Enlightenment medicine…This meticulous reconstruction of his journey from obscure apothecary to London society darling is a vibrant portrait of a surprisingly modern world… Her discussion of Graham’s methods and influences is exhaustive and often illuminating… Doctor of Love is revealing and funny about early attempts to make a science of sex.” - Times Literary Supplement

“Lydia Syson enterprisingly and entertainingly explores the fringes of eighteenth-century science…to give us a brilliant biography of the Scottish apothecary-physician-sexologist-nutritionist-showman Dr James Graham (1745-94).” Women: A Cultural Review

“In her canny and erudite new book, Lydia Syson presents Graham as the first sex therapist, showman and entrepreneur. She navigates a tightrope between Graham as huckster and Graham as physician, and in the process raises important questions for the history of medicine.” - Journal of Medical History

“Wordsworth gave us the egotistic sublime, and Graham the sexual sublime; Lydia Syson has given us a highly enjoyable peep from behind the partition at one of the eighteenth century’s weirdest and most wonderful figures.” - Literary Review

“Syson’s delightful book will engross readers with its marvellous racy material, delivered with the perfect mixture of contextual understanding and fluid, sprightly wit.” - The Lancet

“Superlatives soar off the page in this enjoyable account of Dr. James Graham’s professional life over the course of his career spanning the 1760s to ’90s. Graham was the purveyor of “cutting-edge” medical treatments, most notably electrical therapy, supplemented by magnetism, ether and nitrous oxide, music, and scent. Lydia Syson tackles his relatively short, frequently itinerant, life with wit and intelligence.” – Journal of Historical Biography

“A valuable contribution to the study of sexuality, medicine, and eccentricity in the late eighteenth century. Doctor of Love is, after all, the only book-length biography of Graham; it is, moreover, a very entertaining account of a fascinating eccentric.” – Eighteenth-Century Studies

“Eye-opening.” - Time Out

CLICK ON UNDERLINED TITLES TO READ IN FULL