Lydia Syson's Blog, page 11

April 22, 2013

Come and see the blood in the streets

What prompted thousands of men and women, some only teenagers (like Nat and Felix in A World Between Us), to leave everything they knew to go and help the Republican cause in Spain – often without a word to their families? Many had never left Britain before, most didn’t speak a word of Spanish, and a fifth of them were killed there.

What prompted thousands of men and women, some only teenagers (like Nat and Felix in A World Between Us), to leave everything they knew to go and help the Republican cause in Spain – often without a word to their families? Many had never left Britain before, most didn’t speak a word of Spanish, and a fifth of them were killed there.

In Ken Loach’s Land and Freedom, a documentary film at a political meeting is the deciding factor for the idealistic young volunteer David Carr. Earlier this month, as I watched Ivor Montagu’s astonishingly vivid documentary The Defence of Madrid earlier at a rare screening organised by the London Socialist Film Co-op at the Renoir cinema, I wondered whether the clips in Loach’s film might have come from Montagu’s. I’ve just checked and they didn’t – Land and Freedom is, after all, subtitled ‘A story from the Spanish Revolution’ and quite rightly the archive footage used in it was clearly filmed in Barcelona.

My curiosity about this was pricked by the lively discussion which followed this screening (which was followed by Will the real terrorist please stand up?, a documentary on the relationship between the USA and Cuba). The first speaker from the audience criticised The Defence of Madrid for its lack of revolutionary zeal (demonstrating a point made in my recent post on Homage to Catalonia about the relentless persistence of the idea that Franco won the war because of divisions on the left rather than the combined might of the Italian/German fascist war machine and the Non-Intervention policy spearheaded by Britain.) Jim Jump of the International Brigade Memorial Trust gently pointed out how very different the situations in Barcelona and Madrid were in late 1936 when Montagu went to make the film.

The Spanish capital was then at the start of what became a three-year-long siege by Nationalist forces. General Mola had just coined the term ‘fifth column’, declaring that while four columns of Nationalist soldiers were all too visibly approaching the capital, a ‘fifth’, made up of right-wing sympathisers within the city, was secretly making plans to ensure the invasion was effective. The shock for British audiences of seeing what was actually happening in the Spanish capital must have been intense. Now that we are so horribly used to seeing images showing the effects of aerial bombardment on cities and towns, it’s hard to appreciate the impact news of the war in Spain had around the world. It was the first in Europe in which more civilians than combatants were killed. Last year, when I was interviewing a woman now in her late 80s about her memories of the second world war on Romney Marsh, she told me how horrified she had been as a child to see newsreels of Spanish bombing, and that she remembered turning to her mother in the cinema to say: “It couldn’t happen here, could it?”

The kind of scenes shown in Montagu’s film are considerably more detailed than any  newreel, and of course they did indeed soon become familiar in Britain too. You see houses ripped apart to reveal torn wallpaper, flapping curtains and fireplaces hanging several stories up; people buried under rubble; sandbags in the street; dead children in numbered rows. People look up at the blurred planes crossing the skies above and ask, ‘Are they ours?’, a question echoed in the opening paragraphs of A World Between Us. In a hospital, a wounded Moroccan solider refuses food because he’s been told by his Nationalist masters that the Republicans will try to poison him.

newreel, and of course they did indeed soon become familiar in Britain too. You see houses ripped apart to reveal torn wallpaper, flapping curtains and fireplaces hanging several stories up; people buried under rubble; sandbags in the street; dead children in numbered rows. People look up at the blurred planes crossing the skies above and ask, ‘Are they ours?’, a question echoed in the opening paragraphs of A World Between Us. In a hospital, a wounded Moroccan solider refuses food because he’s been told by his Nationalist masters that the Republicans will try to poison him.

The film is impressionistic and urgent, clearly made in a hurry, under pressure. It has none of the polish of the exquisitely crafted Ministry of Information propaganda films made by Humphrey Jennings to bolster morale on the British Home Front in the early 1940s. The Defence of Madrid is strikingly non-polemical. This is what’s happening, it simply seems to say. What are you going to do about it?

In the audience at the Renoir was Hetty Bower, whom I first met at my grandfather’s funeral, when she told me that she thought his death made her the last surviving member of the Independent Labour Party’s Revolutionary Policy Committee. As she explained at the screening, she knew Ivor Montagu when she was working for Kino Films, the progressive film distribution and production company responsible for arranging screenings of The Defence of Madrid, which was shown at Trade Union and political meetings up and down the country to raise funds for the Brigades and for Medical Aid for Spain, and to draw attention to the urgency of the cause. Typical audiences were women’s co-operative groups and Labour and Communist Party branches. The Edmonton Labour Party raised £72 at one screening, the Rochdale Clarion Cycling Club £38, said BFI curator Ros Cranston, introducing the film.

In the audience at the Renoir was Hetty Bower, whom I first met at my grandfather’s funeral, when she told me that she thought his death made her the last surviving member of the Independent Labour Party’s Revolutionary Policy Committee. As she explained at the screening, she knew Ivor Montagu when she was working for Kino Films, the progressive film distribution and production company responsible for arranging screenings of The Defence of Madrid, which was shown at Trade Union and political meetings up and down the country to raise funds for the Brigades and for Medical Aid for Spain, and to draw attention to the urgency of the cause. Typical audiences were women’s co-operative groups and Labour and Communist Party branches. The Edmonton Labour Party raised £72 at one screening, the Rochdale Clarion Cycling Club £38, said BFI curator Ros Cranston, introducing the film.

Ivor Montagu, who also edited and produced films with Hitchcock, was responsible  for some of the most significant films to be made on the left in the 1930s. The Progressive Film Institute, which he founded, subsequently made four more films about the Spanish Civil War: News from Spain (1937), Crime Against Madrid (1937), Spanish ABC (1938) and Modern Orphans of the Storm (1937). ‘We did what we could’, Montagu said in later life, ‘but it was not enough.’ A circular from the Relief Committee for the Victims of Fascism, which commissioned The Defence of Madrid, announced that this ‘great film’ would be shown twice nightly, December 28th-29th, and that ‘in addition to the Film, the Spanish Situation will be dealt with by the following Speakers: D.N.Pritt, Isabel Brown, Leah Manning, Ivor Montagu’ one of whom was promised to appear at all four screenings. 1000 tickets were issued for each show, at sixpence each.

for some of the most significant films to be made on the left in the 1930s. The Progressive Film Institute, which he founded, subsequently made four more films about the Spanish Civil War: News from Spain (1937), Crime Against Madrid (1937), Spanish ABC (1938) and Modern Orphans of the Storm (1937). ‘We did what we could’, Montagu said in later life, ‘but it was not enough.’ A circular from the Relief Committee for the Victims of Fascism, which commissioned The Defence of Madrid, announced that this ‘great film’ would be shown twice nightly, December 28th-29th, and that ‘in addition to the Film, the Spanish Situation will be dealt with by the following Speakers: D.N.Pritt, Isabel Brown, Leah Manning, Ivor Montagu’ one of whom was promised to appear at all four screenings. 1000 tickets were issued for each show, at sixpence each.

Films like this were clearly life-changing for some who saw them. Even more so was the effect of living through this period in Madrid, as the Chilean poet Pablo Neruda did. As Jim Jump reminded us, it produced Neruda’s poem ‘Let me explain a few things’, recited by Harold Pinter in his 2005 Nobel lecture because he believed it to be the most ‘powerful visceral description of the bombing of civilians’ in contemporary poetry.

And you will ask: why doesn’t his poetry

speak of dreams and leaves

and the great volcanoes of his native land?

Come and see the blood in the streets.

Come and see

the blood in the streets.

Come and see the blood

in the streets!

(The Defence of Madrid is in the BFI National Archive. You’ll find a list of all BFI Spanish Civil War holdings here. The letter quoted comes from the University of Warwick Library’s magnificent resource, Trabajadores – learn more about this amazing archive at History Workshop Online. Find out more about the context of The Defence of Madrid in Ian Aitken’s book Film and reform: John Grierson and the Documentary Film Movement, 1990)

April 10, 2013

Please tell Mr Gove what you think…

We’ve all got until Monday 16th April to respond to the Draft National Curriculum, published subject by subject here, so if you care what happens to the future of education in England (sic) don’t let this opportunity pass. My main concern is obviously with history – read the plans here, and I’m sure you will have something to say about them too.

Then either fill in this questionnaire online or email your response to the Department for Education and Skills to this address: NationalCurriculumReview.FEEDBACK@education.gsi.gov.uk Completing the questionnaire in full is an interesting and useful exercise, but if you are short of time, you can concentrate your energies on responding to question 3, which deals with content. You don’t have to answer all questions.

Many people have responded in public already, and most with great wisdom. In the New Statesman Richard Evans gave an excellent and disturbing account of the process by which the draft history curriculum has been produced. I was also impressed by Martin Spafford’s piece for Hodder Education. He writes that ‘Michael Gove is proposing a history curriculum that rests on an idea of who the British are or have ever been that is demonstrably false and possibly dangerous‘, concluding that ‘A journey through history that erases whole sections of our community and puts them outside the narrative is a journey towards darkness.’ On the Schools History Project website, Spafford explains why he feels Gove’s project is about ‘dumbing down’: ‘No other subject – not the sciences, not geography, not even English – has had its content savaged in the way History has. Scientists, geographers and readers of literature are – to some extent at least – still to be allowed to think. It seems that the selectivity of the attack on History reveals the ideological – rather than educational – base of the proposals.‘

I came across both these articles thanks to the ‘History Not Propaganda’ campaign, which has launched a petition to keep history politically neutral. You can sign it here. Among other important points, the campaign’s website raises concerns about the implications of the proposals for Holocaust education, not least that

‘The nationalist bias behind the whole curriculum might mean that the Holocaust is presented in such a way as to bolster a complacent sense of evils done by ‘foreigners’ whom Britain fought and defeated, rather than a crime of man’s inhumanity to man, in which there was widespread collaboration by local populations across Europe, and in which Britain could easily have been involved had events taken a different course in 1940. This prevents pupils from imbibing some of the deeper, more disturbing, but also more needful philosophical messages of the Holocaust. It also comes perilously close to exploiting the Holocaust to advance a nationalist political agenda.’

The Curriculum for Cohesion has submitted an extremely detailed response to the draft curriculum – find out here why this body believes it to be both unteachable and unlearnable, and the likely effects of a complete absence of content about Islamic civilisation and its relationship to Britain.

Over supper this evening, I told my children about the government’s plans for Key Stage One history: we all tried to imagine teaching a class of thirty five-year-olds the concept of ‘nation’ and ‘civilisation’. (Will the meaning of these words be prescribed, or might that actually be left to an individual teacher’s imagination?) “Has Gove ever met any children?” my daughter asked, in all seriousness.

I could spend the rest of the night detailing my own objections – I touched upon some of them in an interview published last week in the Camden New Journal - but I’ve promised my editor my revised manuscript of THAT BURNING SUMMER by Monday, so it’s back to 1940 for me now.

Many aspects of the proposals make me very angry. What makes me very sad is that rather than giving children and young people the tools for a passionate engagement with history that could and should lead to a lifetime of continued learning and interest in the past – of Britain and the rest of the world – these reforms (if they go ahead) actually risk alienating vast numbers of children from the subject of history for the rest of their lives.

(If you’re also interested in responding to the Citizenship draft curriculum, you’ll probably find Amnesty’s webpages on the subject very helpful.)

April 5, 2013

11th July 2013 Branford Boase Award Ceremony

‘The BBA was set up to reward the most promising new writers and their editors, as well as to reward excellence in writing and in publishing. The Award is made annually to the most promising book for seven year-olds and upwards by a first time novelist.’ Find out more….

‘The BBA was set up to reward the most promising new writers and their editors, as well as to reward excellence in writing and in publishing. The Award is made annually to the most promising book for seven year-olds and upwards by a first time novelist.’ Find out more….

Here’s the full 2013 Shortlist:

April 4, 2013

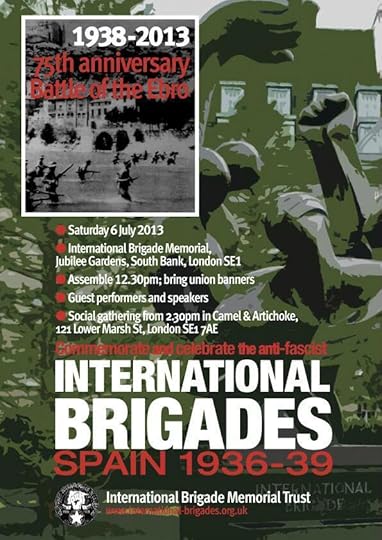

6th July 2013 IBMT Annual Commemoration

March 14, 2013

Left out

I’m developing a new obsession, fuelled this week by a number of chance media encounters. Today I read an article by Mariko Oi reflecting on her own extremely selective education in history as a teenager in Japan – just nineteen pages of a textbook were devoted to events which took place between 1931 and 1945. Oi then outlined the ‘curriculum battles’ taking place in Japan right now. While Nobukatsu Fujioka and his Japanese Society for History Textbook Reform regard the majority of current textbooks as “masochistic”, putting Japan only in a negative light, historian Tamaki Matsuoka believes the very opposite is true. She says that a number of the country’s foreign relations difficulties can be put down its stance on history in schools:

“Our system has been creating young people who get annoyed by all the complaints that China and South Korea make about war atrocities because they are not taught what they are complaining about…It is very dangerous because some of them may resort to the internet to get more information and then they start believing the nationalists’ views that Japan did nothing wrong.”

Earlier this week I listened to Edmund de Waal talking about his grandmother’s posthumously published and distinctly autobiographical novel about returning to Austria as an exile after the Second World War. He commented on the very different approaches taken now to the history of the same period in Austria and Germany. I was delighted to discover last month that ‘A World Between Us’ will be translated into German, and interested to see on my German publisher’s list – among a number of issue-based Young Adult novels about teenage alcoholism, bullying and anorexia – a story about a teenager’s difficulties in extricating himself from a far right youth group. Now I wonder whether a book like that would find as ready an audience in Austria as in Germany.

The Anne Frank Trust travelling exhibition was hosted this term by Elmgreen School in South London – culminating in a visit by Holocaust survivor Herbert Levy, which I was invited to attend. The message he left the students with – ‘Never again’ – rests on the assumption that only by talking and remembering the past can we prevent the repetition of atrocities. When I went to talk to some of the same year 9s a few weeks later, they were surprised to hear what a very different approach Spain has until recently taken to the idea of ‘never again’.

This is a hasty post, as I’m off to two events on related subjects this afternoon – a seminar on Middle class recruits to Communism in 1930s Britain at Gresham College, followed by a discussion at LSE with Paul Preston, Daniel Beer, Helen Graham and Dan Stone: Franco’s Terror in a European Context. Both should be available to view online in the next few weeks. Two brilliant examples of the kind of high quality, accessible-to-all history events for which our higher education institutions should be celebrated. Long may they last.

What do you feel got left out of your historical education when you were growing up? And how have you filled the gaps since?

March 5, 2013

27th June 2013 WeRead Prize Day

I’ll be taking part in a day of readings, discussion and voting at UCS School in North London will decide the winner – see below for full shortlist, and check out the website to find out how your school can take part.

The Weight of Water by Sarah Crossan (Bloomsbury)

The Glass Collector by Anna Perera (Puffin)

Duty Calls: Battle of Britain by James Holland (Puffin)

Department 19 by Will Hill (Harpercollins)

Code Name Verity by Elizabeth Wein (Electric Monkey)