Lydia Syson's Blog, page 10

August 5, 2013

Book Genes

Every book has its own peculiar literary heritage, a kind of textual DNA that can be as hard to map as the Genome Project. I’m in danger of muddling my metaphors here, but I thought I’d write today about some of the book genes that have fed into That Burning Summer, books I first read or had read to me so long ago they were half-forgotten when I started writing this new novel. I was vaguely conscious of a few of these influences from the outset; others gradually dawned on me as I wrote, or have even been revealed since.

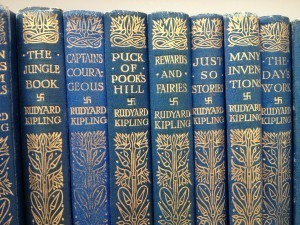

Romney Marsh was a place I knew very well through books long before I ever actually set eyes on it, in my late twenties. When I was very small, my father read a lot of Kipling to me and my brother and sister. Somehow it never occurred to me then that the poems and stories I loved in Puck of Pook’s Hill and Rewards and Fairies were actually about real places I might one day visit.

I ever actually set eyes on it, in my late twenties. When I was very small, my father read a lot of Kipling to me and my brother and sister. Somehow it never occurred to me then that the poems and stories I loved in Puck of Pook’s Hill and Rewards and Fairies were actually about real places I might one day visit.

If you know the tale ‘Dymchurch Flit’, you might remember Ralph Hobden’s magical description of the Marsh ‘back behind of’ Rye:

‘”…there’s steeples settin’ beside churches’ and an’ wise women settin’ beside their doors, an’ the sea settin’ above the land, an’ ducks herdin’ wild in the diks” (he meant ditches). “The Marsh is justabout riddled with diks an’ sluices, an’ tide-gates an’ water-lets. You can hear ‘em bubblin’ an’ grummelin’ when the tide works in ‘em, an’ then you hear the sea rangin’ left and right-handed all up along the Wall. You’ve seen how flat she is – the Marsh? You’d think nothin’ easier than to walk eend-on acrost her? Ah, but the diks an’ the water-lets, they twists the roads about as ravelly as witch-yarn on the spindles. So ye get all turned round in broad daylight.”‘

‘”…there’s steeples settin’ beside churches’ and an’ wise women settin’ beside their doors, an’ the sea settin’ above the land, an’ ducks herdin’ wild in the diks” (he meant ditches). “The Marsh is justabout riddled with diks an’ sluices, an’ tide-gates an’ water-lets. You can hear ‘em bubblin’ an’ grummelin’ when the tide works in ‘em, an’ then you hear the sea rangin’ left and right-handed all up along the Wall. You’ve seen how flat she is – the Marsh? You’d think nothin’ easier than to walk eend-on acrost her? Ah, but the diks an’ the water-lets, they twists the roads about as ravelly as witch-yarn on the spindles. So ye get all turned round in broad daylight.”‘

All true, of course. And now I know all the places in it too, the poem ‘Brookland Road’ makes me tingle all the more:

I was very well pleased with what I knowed,

I reckoned myself no fool –

Till I met with a maid on the Brookland Road,

That turned me back to school.

Low down-low down!

Where the liddle green lanterns shine –

O maids, I’ve done with ‘ee all but one,

And she can never be mine!

‘Twas right in the middest of a hot June night,

With thunder duntin’ round,

And I see her face by the fairy-light

That beats from off the ground.

She only smiled and she never spoke,

She smiled and went away;

But when she’d gone my heart was broke

And my wits was clean astray.

O, stop your ringing and let me be –

Let be, 0 Brookland bells!

You’ll ring Old Goodman out of the sea,

Before I wed one else!

Old Goodman’s Farm is rank sea-sand,

And was this thousand year;

But it shall turn to rich plough-land

Before I change my dear.

O, Fairfield Church is water-bound

From autumn to the spring;

But it shall turn to high hill-ground

Before my bells do ring.

O, leave me walk on Brookland Road,

In the thunder and warm rain –

O, leave me look where my love goed,

And p’raps I’ll see her again!

Low down – low down!

Where the liddle green lanterns shine –

O maids, I’ve done with ‘ee all but one,

And she can never be mine!

And how could I resist slipping ‘A Smuggler’s Song’ into That Burning Summer? ( ’All Marsh folk has been smugglers since time everlastin’ says Tom Shoesmith – or Puck. ‘Twould be in her blood to listen out o’ nights.’)

As a child I never made the connection between these smugglers and the Owlers I read about in the works of another author I devoured at the time: Monica Edwards. (The White Riders was a particular favourite). It was thanks to Monica Edwards that I knew all Lookers and sheepshearing and fishing for eels on the Marsh. I also had no idea that one of my all-time-favourite-authors E.Nesbit was buried on the Marsh.

As a child I never made the connection between these smugglers and the Owlers I read about in the works of another author I devoured at the time: Monica Edwards. (The White Riders was a particular favourite). It was thanks to Monica Edwards that I knew all Lookers and sheepshearing and fishing for eels on the Marsh. I also had no idea that one of my all-time-favourite-authors E.Nesbit was buried on the Marsh.

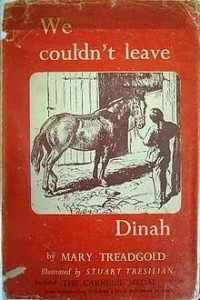

I’ve always loved plots of concealment – the idea of a child hiding a stranger who could be either friend or foe. Here my early influences are Bette Greene’s The Summer of my German Soldier (1973) and Barbara Leonie Picard’s The Young Pretenders (written in 1971, set in 1745). Mary Treadgold’s We Couldn’t Leave Dinah (Channel Island occupation, a cave hideaway, spies and ponies to boot), Noel Streatfeild’s When the Siren Wailed and Nina Bawden’s Carrie’s War are all buried deep in my psyche too, along with The Other Way Round.

(Channel Island occupation, a cave hideaway, spies and ponies to boot), Noel Streatfeild’s When the Siren Wailed and Nina Bawden’s Carrie’s War are all buried deep in my psyche too, along with The Other Way Round.

(And here I confess to having become a blushing wreck as I declared my love to Judith Kerr at Tales on Moon Lane earlier this summer.)

And finally, as I realised when I watched the incredible production of Othello at the National last month, this was the play which long ago established a model for falling in love that has never left me:

‘She loved me for the dangers I had pass’d,

And I loved her that she did pity them.’

When you’ve read That Burning Summer, you’ll understand.

Links for the Kipling Society and the Monica Edwards Appreciation Society.

July 23, 2013

This Burning Summer

I remember last July as dreary and overcast. When I went walking on Romney Marsh, trying to soak up the atmosphere for the new novel I was writing, it was hard to summon up a real sense of ‘that torturingly beautiful summer’ of 1940, as H.E.Bates described it in his autobiography,The Ripening World. For some reason, the dramatisation of his novel Love for Lydia, televised the year I went to secondary school, and the teasing I got as a result of it, put me off reading Bates almost forever. And then I came across his description of the Battle of Britain:

‘…geographically, of course, it covered no more than a tiny fraction of Britain. The area of combat took place in a cube roughly eighty miles long, nearly forty broad and five to six miles high. The vortex of all this was the Maidstone, Canterbury, Ashford, Dover, Dungeness area, in which Spitfires largely operated, with the further rear centre of combat between Tunbridge Wells, Maidstone and London, largely commanded by Hurricanes. Sometimes in the frontal area as many as 150 to 200 individual combats would take place in the space of half an hour.

‘…geographically, of course, it covered no more than a tiny fraction of Britain. The area of combat took place in a cube roughly eighty miles long, nearly forty broad and five to six miles high. The vortex of all this was the Maidstone, Canterbury, Ashford, Dover, Dungeness area, in which Spitfires largely operated, with the further rear centre of combat between Tunbridge Wells, Maidstone and London, largely commanded by Hurricanes. Sometimes in the frontal area as many as 150 to 200 individual combats would take place in the space of half an hour.

To the civilian population below, who were able to see something of a battle for the possession of their island for the first time for centuries, the entire affair was strangely, uncannily, weirdly unreal. The housewife with her shopping basket, the farm labourer herding home his cows, the shepherd with his flock, the farmer turning his hay: all of them, going about their daily tasks, could look up and see, far, far above them, little silver moths apparently playing against the sun in a game not unlike a celestial ballet. Now and then a splutter of machine-gun fire cracked the heavens open, leaving ominous silence behind. Now and then a parachute opened and fell lazily, like a white upturned convolvulus flower, through the midsummer sky. But for the most part it all had a remoteness so unreal that the spectator over and over again wondered if it was taking place at all. Nor was it often possible to detect if the falling convolvulus flower contained enemy or friend, and often the same was true of aircraft, so that the battle was watched in the strangest state of suspense, with little open or vocal jubilation.’

It was easy to imagine this last weekend, which I spent on the South Downs, transported back in time as I walked through a green and gold landscape which looked once more as if it were waiting for Paul Nash to take up his paintbrush.

It was easy to imagine this last weekend, which I spent on the South Downs, transported back in time as I walked through a green and gold landscape which looked once more as if it were waiting for Paul Nash to take up his paintbrush.

Earlier this month, when we were celebrating my mother’s birthday earlier this month – a balmy evening in the garden – I belatedly realised that she had actually been born in the burning summer of my new novel’s title. It was just a month after Dunkirk and the fall of France, hot on the heels of the collapse of Denmark, Norway, Belgium, and the Netherlands, and Britain was gearing up for invasion itself. As active Communists and anti-fascists, my grandparents were under no illusions about how they were likely to be treated in the event of a Nazi take-over in Britain. They asked my mother’s godmother to bring her up if they ended up in prison, or worse.

My father was born in 1939, six months before the outbreak of war. But both my parents were teenagers by the time rationing finally came to an end – with a huge celebration in Trafalgar Square. My mother has often told us of the excitement of eating her first ever orange, and she is inconsistently convinced that her persistent and violent dislike of bananas is all down to early deprivation.

My father was born in 1939, six months before the outbreak of war. But both my parents were teenagers by the time rationing finally came to an end – with a huge celebration in Trafalgar Square. My mother has often told us of the excitement of eating her first ever orange, and she is inconsistently convinced that her persistent and violent dislike of bananas is all down to early deprivation.

The effects of all this lingered on. Accompanying any reprimand for wastefulness during my own childhood was the phrase: ‘I was brought up in the war, you know….’

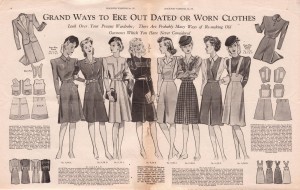

It’s a form of puritanism I’ve absorbed utterly. Don’t throw that away, I cry repeatedly. You never know… We could use it for x or y or z. It might come in useful. I still have button collections and material boxes, clothes I’ve worn since I was sixteen and cotton reels and poppers that belonged to my grandparents. I don’t take the ‘make-do-and-mend’ mentality quite as far as my father’s mother did. (She was always known as Country Granny – our Communist Granny was London Granny). She continued

It’s a form of puritanism I’ve absorbed utterly. Don’t throw that away, I cry repeatedly. You never know… We could use it for x or y or z. It might come in useful. I still have button collections and material boxes, clothes I’ve worn since I was sixteen and cotton reels and poppers that belonged to my grandparents. I don’t take the ‘make-do-and-mend’ mentality quite as far as my father’s mother did. (She was always known as Country Granny – our Communist Granny was London Granny). She continued  to crochet her own dishcloths till she was in her nineties, posting them to friends up and down England, and always kept a collection of slimy soap scraps out of which new bars could be formed. I vividly remember sitting at her feet as a child with my hands held out, like June in That Burning Summer, while Country Granny unravelled the wool from old jerseys to turn into socks. Which in turn were always darned, of course, when the heels went to holes.

to crochet her own dishcloths till she was in her nineties, posting them to friends up and down England, and always kept a collection of slimy soap scraps out of which new bars could be formed. I vividly remember sitting at her feet as a child with my hands held out, like June in That Burning Summer, while Country Granny unravelled the wool from old jerseys to turn into socks. Which in turn were always darned, of course, when the heels went to holes.

So I must confess I rather enjoyed embracing the wartime spirit and turning the clock back to imagine myself in 1940 while writing the book, listening to old radio broadcasts, reading wartime cookery books and wondering what it would be like to look up and see an unidentifiable human being floating down from the heavens.

July 19, 2013

Branford Boase Award Party

A week on and I’m still getting over the glorious celebration of books, reading, writing and above all editing for children that is the Branford Boase Award and Henrietta Branford Writing Competition. The BBA winning double-act of Dave Shelton and David Fickling said it all: their chalk-and-cheese speeches gave a brilliant flavour of the kind of chemistry between author and editor that gets results as superbly maverick as A Boy and a Bear in a Boat, as well as the absolutely crucial role played by the BBA in supporting and giving confidence to debut children’s novelists.

Dave Shelton (left)

& David Fickling (below)

I’ve felt lucky beyond belief ever since meeting my own editor, Sarah Odedina, for the first time. The new Hot Key Books office in Clerkenwell was still almost empty in the autumn of 2011 – all echoing walls, bare shelves and vacant desks. Discovering that my book was to be on the launch list was as daunting as it was thrilling. I realised then that Sarah knew far better than I did exactly what A World Between Us was really all about. I’ve learned so much from her since then – about voice, and instinct, and being true to oneself, and why passion is so important in publishing. What a huge honour to find myself stepping up with her last week to receive our lovely ‘Highly Commended’ prizes from one of the prize’s main sponsors, Jacqueline Wilson (yes, really!) and Annabel Pitcher, last year’s BBA winner for the fantastic My Sister Lives on the Mantlepiece.

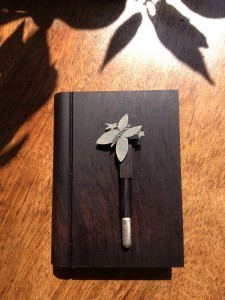

Inside our boxes we each had this beautiful wooden book and silver butterfly pin.

After the awards there was a great frenzy of signing…here’s Grace Davis, one of the Writing Competition Winners, getting her pile of Jacqueline Wilson books sorted out:

Edward Hogan signing Daylight Saving for young writer Ella McElligott

Natasha Farrant signing The Things We Did For Love for Charlotte Cohen

Alexia Sloan

& James Martin (with proud parents)

Maximilian Allanby-Bassett was on his school journey and couldn’t come but his sister Isabelle did an excellent job of collecting both his prize and plenty of signatures.

You can read all these young writers’ winning stories here – and I wouldn’t be surprised if you don’t see their names on spines in bookshops in years to come.

As fate would have it, we had just lent our own family copy of A Boy and a Bear in a Boat to a friend (and it was the lovely original hardback with the coffee-’stained’ cover too). We remembered too late to retrieve and add it to the bag of other shortlisted books my own youngest children had brought along to get signed. Wendy Meddour drew them a chicken picture, to their great delight.

It was altogether an extraordinary and inspiring evening, and we had to pinch ourselves all the way home, especially after this encounter with Philip Pullman….

Photographs by Paul Carter – see lots more at the BBA & HBWC website and find out about all the winning young writers and shortlisted authors.

June 28, 2013

‘Deberemos resistir! We must resist!’

I don’t know if you remember the moment in A World Between Us when George, walking along a street in besieged Madrid, finds himself humming along to ‘Ay Carmela’, one of the best known Republican songs of the Spanish Civil War. Well, now’s the time to join in too – if not with the song, then with the sentiment.

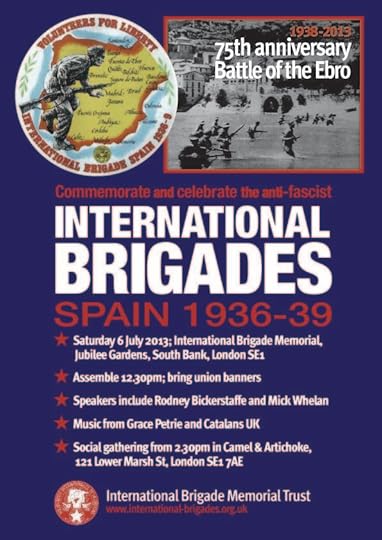

The sole monument to the International Brigades in Madrid  was put up less than two years ago, and already it’s under threat. For the time being at least, you’ll find it at University City, once a frontline in the fighting (David Lomon gave a speech at the monument’s inauguration). Before long, it had been vandalised, with graffiti calling the volunteers ‘murderers’. Earlier this month, judges in Spain ruled that it was in breach of planning regulations, and ordered the University to take it down.

was put up less than two years ago, and already it’s under threat. For the time being at least, you’ll find it at University City, once a frontline in the fighting (David Lomon gave a speech at the monument’s inauguration). Before long, it had been vandalised, with graffiti calling the volunteers ‘murderers’. Earlier this month, judges in Spain ruled that it was in breach of planning regulations, and ordered the University to take it down.

Newsnight’s economics editor Paul Mason wrote last year of the recent resurgence of the far right in Spain. ’Austerity’ has become an easy excuse to suppress vitally important historical memory projects that have only become possible in the past decade or so.

David Mathieson set out the background to the attack on the International Brigade monument in an excellent ‘Comment is Free’ piece in The Guardian a few weeks ago: despite the ‘scores of streets and squares in Madrid that still bear the names of members of the Franco regime, let alone monuments such as the Arco de la Victoria that celebrate the crushing of one half of the population, it now seems that political spite will do away with the only commemorative plaque to the International Brigades in the entire city.’

There are four things you can easily do to show international solidarity with the defenders of the memory of the international anti-fascist volunteers, 10,000 of whom gave their lives to the cause:

- Sign this petition (It’s in Spanish, but see below for a rough translation – courtesy of Google Translate I’m afraid)

- Ask your MP (if s/he isn’t a minister or shadow minister) to support the Early Day Motion 204 calling on the British government to make representations to the Spanish government about the threat to the Madrid memorial.

- Tell as many people as you can about the issue, and encourage them to do the same.

- Visit London’s own IB memorial at the South Bank, and join in with the IBMT’s annual commemoration in London on July 6th…see below for full details.

Find more information on the International Brigade Memorial Trust blog and in The Volunteer, the journal of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade Archives, a report on a recent demonstration at the memorial in Madrid on the website of the Associación de Amigos de las Brigradas Internacionales, and a map of other IB memorials around Spain.

Very rough translation of petition text:

Diligence (?) submitted by the TSJM to Court No. 22 administrative litigation Madrid confirms the initial sentence of this-which declared invalid the installation of the monument to the International Brigades, and gives the UCM within ten days to confirm receipt of that judgment. Once acknowledgment sent, the Rector of the Complutense has two months to remove the monument placed outside the building of the Campus Student Complutense.

The monument was sponsored by the Friends of the International Brigades, which means Allego for funding (Complutense University, despite the lies propagated by the right wing press, has not set any background). Its design was the result of the generous contribution by a faculty committee of the Faculty of Fine Arts. The newly elected Rector of Complutense, Jose Carrillo, which opened on October 22, 2011, on the 75th anniversary of the brigades. That same day came the news that a private attorney, Miguel Garcia Jimenez, had filed an administrative appeal against this opening.

The Court No. 22 at the time decided to deny the preliminary injunction asking the lawyer consisting paralyze the installation, and thus the inauguration of the monument. But the resource processed by ordinary and issued its first ruling in April 2012, declaring “null” placement in April 2012 for lack of license and for taking the Rector “a power that does not belong” by failing to university bodies the installation.

The ruling was immediately appealed by the UCM to the TSJM. Meanwhile, it was a favorable report from the Madrid regarding the protection of archaeological and asked the City Council UCM building permit, request that despite the time lag has not been answered yet.

In January 2013 was communicated to the complainant an TSJM judgment, a judgment that has not reached the UCM until mid-May 2013, notice of which was within 10 days to the acknowledgment. This judgment confirms the initial Court No. 22 administrative litigation to declare null the installation of the monument, arguing that the actions of the UCM “is not just a procedural error in processing the license or a deficiency in the project or authorization obtained, review all questions of law, but a complete and utter failure of the procedure. “Universidad Complutense” proceeded to perform a behavior in fact, the installation of a monument in the public domain ground university, quite apart from any urban process that amparase the facility, which would tend to control their condition. “

Not know until now what will be the decision of the Rector of the UCM, although some information (see the newspaper El Mundo, June 3) Joseph Carrillo advance will not remove the monument as it was already said license for the same , remembering that some other monuments, such as the 11-M in Madrid, were opened without the previous license and had no problem.

The AABI will soon issue a statement about it, but from right now ask everyone who loves democracy and justice to express their support by writing to our address on the web, facebook or twiter.

To:

Citizens.

Do not withdraw the International Brigades Memorial at UCM

Sincerely,

[Your name]

June 23, 2013

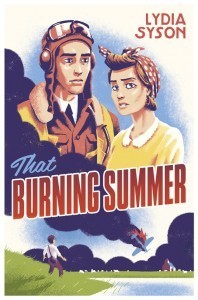

Cover Glory

I did wonder whether second novel covers might be like second babies.

Accompanying their gestation comes that sneaking anxiety that you’ll never be able to love the next quite as much as you loved the first. So insidious, and yet, I’m delighted to say in both cases, so quickly overturned.

I couldn’t be luckier in my illustrator, Jan Bielecki,  who has a genius for getting to the very heart of a book. In the case of That Burning Summer, perhaps his Polish background made this easier than usual. My romantic hero, Henryk, is a pilot who escapes Poland after the German and Soviet invasions of September 1939, and eventually finds himself in England, and in trouble.

who has a genius for getting to the very heart of a book. In the case of That Burning Summer, perhaps his Polish background made this easier than usual. My romantic hero, Henryk, is a pilot who escapes Poland after the German and Soviet invasions of September 1939, and eventually finds himself in England, and in trouble.

As you can see, the new spine goes beautifully with that of A World Between Us, while the back cover is a work of art in itself. A drumroll now for the ‘blurb reveal’, and of course, the now famous HOT KEY RING…

And yes, in case you’re wondering, this is indeed the novel formerly known as Winged – you may have seen my ‘work-in-progress’ report on it for last year’s The Next Big Thing meme.

June 21, 2013

A small shout about…

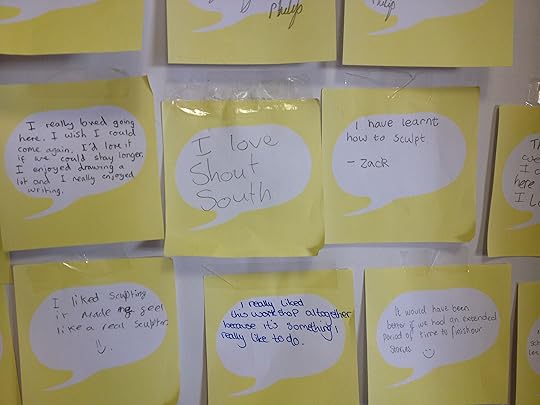

This time last week I was contemplating the hidden qualities of a household sponge with a small group of Tigers . . . it was  Day Two of Shoutsouth! – the creative writing festival for South London children held at London South Bank University - and in Margaret Bateson-Hill‘s ‘Mad, Moody and Murky’ workshop, we were exploring the arts of focus, pacing and creating atmosphere. Elsewhere in the room, other budding writers and illustrators were getting to grips with an intriguing piece of driftwood, an exotic shell and a yellow rubber glove.

Day Two of Shoutsouth! – the creative writing festival for South London children held at London South Bank University - and in Margaret Bateson-Hill‘s ‘Mad, Moody and Murky’ workshop, we were exploring the arts of focus, pacing and creating atmosphere. Elsewhere in the room, other budding writers and illustrators were getting to grips with an intriguing piece of driftwood, an exotic shell and a yellow rubber glove.

Along the corridor, twelve more practising writers and illustrators were drawing ideas from teams of Leopards, Lions and Panthers – nearly a hundred children aged 9-13 with teachers and librarians from primary and secondary schools across Southwark, Lambeth, Lewisham and Wandsworth. I don’t think any of us there were entirely prepared for the rush of creative energy that poured out of this great mix of ages, schools and backgrounds. By Saturday, everybody, including accompanying adults from home and school – had a story on the go.

A few months ago, when I became part of CWISL – Children’s Writers and Illustrators in South London – I was excited by the prospect of joining a like-minded local(ish) group whose raison-d’être wasn’t promoting their own books, but getting together to find and share ways to excite young people about books, reading, illustration and writing more generally. Having seen the huge changes in my own children’s primary school over the past six years or so, I felt pretty passionate about this idea. The kind of free-flowing story-writing that always used to happen in schools, and which certainly helped get me started as a writer, seems to have mutated now into highly structured and fairly rigid exercises in something they call ‘literacy’. Children have little opportunity to roam where their minds take them. Teachers are operating under ever-increasing pressure. As Sally Gardner pointed out in her Carnegie acceptance speech this week, it’s getting harder and harder for schools to nurture imagination – and easier and easier to test children into failure.

A few months ago, when I became part of CWISL – Children’s Writers and Illustrators in South London – I was excited by the prospect of joining a like-minded local(ish) group whose raison-d’être wasn’t promoting their own books, but getting together to find and share ways to excite young people about books, reading, illustration and writing more generally. Having seen the huge changes in my own children’s primary school over the past six years or so, I felt pretty passionate about this idea. The kind of free-flowing story-writing that always used to happen in schools, and which certainly helped get me started as a writer, seems to have mutated now into highly structured and fairly rigid exercises in something they call ‘literacy’. Children have little opportunity to roam where their minds take them. Teachers are operating under ever-increasing pressure. As Sally Gardner pointed out in her Carnegie acceptance speech this week, it’s getting harder and harder for schools to nurture imagination – and easier and easier to test children into failure.

But back to CWISL. Was I free to take part in a festival in mid-June? Beverley Birch wondered. Oh yes, I said cheerfully, not knowing quite where it would lead, little guessing I’d be up to my ears just then in page proofs of That Burning Summer, reeling from the joys and pressures of Hot Key’s speedy new in-house typesetting system.

I’ve recovered from that, but I’m certainly still reeling from the sheer exhilaration of taking part in Shoutsouth! 2013. Why was the event so special? Perhaps because it had the power to create ripples extending through the lives of young people way beyond the two intense out-of-school days they spent taking part in workshops.

First things first. Margaret told us a story. It couldn’t have been simpler. No props. No paper. Just her voice, her words, and our ears. The story was one she’d first read when she was nine, in Andrew Lang’s Olive Fairy Book.

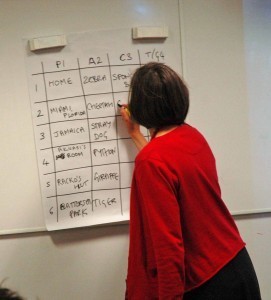

Then the groups of big cats went off to get to know each other. Each team started with ‘The Spark: Recycle Reality’ – lots of ideas of getting ideas. Here am I, taking character suggestions for ‘The Grid’ (with many thanks to Amanda Swift for introducing me to this game).

Here’s Gillian Cross plotting a path through plot structure with a game of ‘Rigmarole’. In this case, think giant toads, carrier pigeons, remote Scottish castles, child-catchers…

And here we’re dramatising and freeze-framing emotion with Mo O’Hara (spot author AND teacher Sarah Mussi looking on)…

…and modelling character, most literally, with Anne Marie Perks

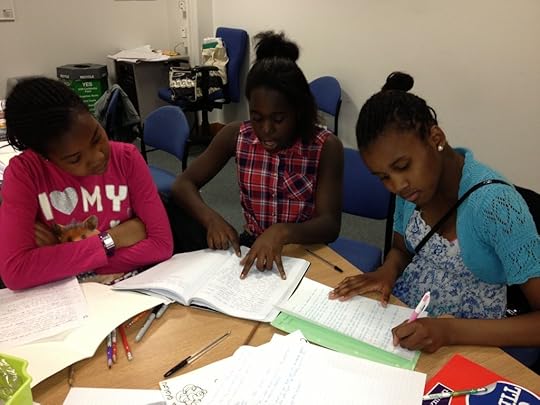

On Saturday, the vast majority of children came back voluntarily – rushed back, really – to continue work on their stories, pictures and models. It was incredibly rewarding to see how directly they were responding to the ideas they’d just absorbed – these girls are reading their work out aloud to each other:

We also enjoyed a party, signings and a bookshop (provided by Under the Greenwood Tree).

But, as I said, the ripples went so much further than this, and in every direction too. Before the festival even kicked off, writers and illustrators went in twos and threes to meet participating schools in local libraries – a chance not just to introduce ourselves and our work to more pupils than could possibly actually attend, but also for years 5-8 students to talk to librarians, get signed up with library cards, and find out how to reserve the book you really want. I’d already had planning meetings with my fellow ‘Sparkies’ (Sara Grant, Mo O’Hara and Karen Owen) and Tigers (Margaret, Gillian and Anne-Marie), but I was as intrigued as our young audiences to hear from Patricia Elliott and Bridget Strevens-Marzo about how they got started. (You can read Bridget’s take on Southshout here - and find out about an amazing coincidence we discovered when we first met.)

Before long, participants will see their work going up on the Shoutsouth festival website, and also published online in the creative writing magazine, Shoutabout. Anyone under sixteen can contribute to that, so we’re hoping to see work coming in soon from friends, schoolmates and family members too.

Then there was the setting. Few of the children who came had set foot in a university before. After listening to LSBU outreach workers Ken and Lacarna, most of them thought they’d like to come back. What more could you ask of one event? Aspirations were raised, imaginations sparked, skills shared, pleasure multiplied…. All we need next time is funding. Please.

More people contributed time, materials and expertise than I’ve been able to mention here by name. Find out about them all on the Shoutsouth website.

June 6, 2013

Unbelievable?

‘Isn’t that rather implausible?’

I’ll take a bet that if you write vampire novels or fantasy or dystopia for young people, that’s not a question you get asked very often. But credibility is important for all kinds of writing. When it comes to historical fiction, it’s a must.

There’s just one problem. A huge part of the pull of writing about the past is delight in the extraordinary stories you find there. Take the eighteenth-century doctor who designed a live-turtle-dove-topped electrified bed which played music as its occupants made love - Dr James Graham also lectured the cream of London society on ice-cold post-coital bathing of the genitals and indulged in earth-bathing. Or the peasant who was inspired by Robinson Crusoe to cross West Africa and the Sahara in disguise, and became the first European to enter Timbuktu and survive  to tell the tale, only to be caught up in Anglo-French political rivalry and accused of theft and deception. My latest YA novel, out in October, is inspired by the incredible journeys made by airmen in the Polish Air Force to continue the fight ‘for their freedom and ours’, and the fighter planes which plunged 30 feet or more into the ground when they crashed during the Battle of Britain, whose pilots were buried with them.

to tell the tale, only to be caught up in Anglo-French political rivalry and accused of theft and deception. My latest YA novel, out in October, is inspired by the incredible journeys made by airmen in the Polish Air Force to continue the fight ‘for their freedom and ours’, and the fighter planes which plunged 30 feet or more into the ground when they crashed during the Battle of Britain, whose pilots were buried with them.

In the case of A World Between Us, I thought particularly long and hard about Felix’s escape in Paris. The woman who first got me interested in the Spanish Civil War convinced me that it could have happened: the funniest, cleverest and most committed of all the Mitford sisters, Jessica. She’s long been a heroine to me. Months after finishing writing my novel, I couldn’t have been more thrilled to discover that her top Desert Island Disc choice was ‘The Peat Bog Soldiers’, the song Kitty teaches Felix as they travel through Spain.

Jessica Mitford’s story is wonderfully told in her autobiography Hons and Rebels and it’s well known. Barely a week after having met and fallen for her cousin Esmond Romilly (and the Spanish cause too), they ran away to Spain together. She told her parents she was staying with friends in Dieppe. When I first read the book as a teenager, it established a gold standard for romantic elopement for me. Clearly, politics didn’t get more passionate than in the Spanish Civil War.

Jessica Mitford’s story is wonderfully told in her autobiography Hons and Rebels and it’s well known. Barely a week after having met and fallen for her cousin Esmond Romilly (and the Spanish cause too), they ran away to Spain together. She told her parents she was staying with friends in Dieppe. When I first read the book as a teenager, it established a gold standard for romantic elopement for me. Clearly, politics didn’t get more passionate than in the Spanish Civil War.

But plenty of forgotten activists volunteered to fight or nurse for Spain with equal spontaneity. The artist Felicia Browne was on a driving holiday through France and Spain with her friend Edith Bone when the military coup that started the Spanish Civil War began in July 1936. By the 3rd August she had joined a militia and was on her way to the front, the only British woman actually to fight in the war, and the first of over 500 British volunteers to die. She was killed within three weeks, apparently shot dead while trying to help an injured Italian comrade during an ambushed attempt to blow up a rebel train.

An equally tragic and heroic figure is John Cornford, whose  moving poem ‘Heart of the Heartless World’ is printed in A World Between Us. A committed Cambridge communist, he arrived in Spain on August 8th 1936 as a journalist, but quickly decided that as he didn’t speak a word of Spanish, he’d be rather more valuable fighting than writing news reports.

moving poem ‘Heart of the Heartless World’ is printed in A World Between Us. A committed Cambridge communist, he arrived in Spain on August 8th 1936 as a journalist, but quickly decided that as he didn’t speak a word of Spanish, he’d be rather more valuable fighting than writing news reports.

Felicia Browne had been heading for Barcelona for the alternative People’s Olympiad, planned as an alternative to the ‘Nazi’ Olympics in Berlin, but aborted at the outbreak of war. Two Jewish garment workers from Stepney, Nat Cohen and Sam Masters, were cycling to Barcelona when they heard the news of the uprising, immediately joined the militia, and Nat Cohen became Esmond Romilly’s commander in the Tom Mann Centuria. Another artist, Wogan Phillips, who was  then married to writer Rosamund Lehmann (Invitation to the Waltz, Dusty Answer, The Echoing Grove….), was also on holiday in Spain when war broke out. The Eton-educated son of a wealthy ship-owner, he immediately offered his services to the Spanish Medical Aid Committee, bought a van, loaded it with medical supplies, and drove to the Jarama front.

then married to writer Rosamund Lehmann (Invitation to the Waltz, Dusty Answer, The Echoing Grove….), was also on holiday in Spain when war broke out. The Eton-educated son of a wealthy ship-owner, he immediately offered his services to the Spanish Medical Aid Committee, bought a van, loaded it with medical supplies, and drove to the Jarama front.

Once the International Brigades had been formed, Paris became their organising centre and the city secretly began to throng with ‘volunteers for liberty’ from all over the world. Scottish volunteer John Lochore was one of many to arrive on a weekend excursion ticket in the winter of 1936:

‘…we duly arrived in the French capital and on leaving the station, by presenting our secret address to the driver, we were whizzed through a maze of streets…I am sure the entire fleet of taxi drivers in Paris knew the address – a fact which was revealed by their casual confidence in conveying us to our “secret destination”.’

John Sommerfield, a young Communist novelist from Hampstead, was early to sign up at the Place du Combat. Of the many stories grippingly told and quoted by Richard Baxell in his recent book Unlikely Warriors, Sommerfield’s is one of the most amusing:

John Sommerfield, a young Communist novelist from Hampstead, was early to sign up at the Place du Combat. Of the many stories grippingly told and quoted by Richard Baxell in his recent book Unlikely Warriors, Sommerfield’s is one of the most amusing:

‘We advanced to the table, said our piece, were handed forms, and went through complications of translations. What was my job? Author, perhaps? The French word was écrevasse? Something like that. But no, it turned out to be écrivain. Ecrevasse was a lobster. “Sommerfield, the celebrated English revolutionary lobster.” It was a crack to last for weeks.’

Between leaving Glasgow and arriving in Paris. Steve Fullarton aged from eighteen to twenty-one. He was one of the hundreds (former milkmen, maths lecturers, actors, sailors…) who risked arrest and endured a terrifying night climb of the snow-capped Pyrenees in rope-soled sandals, smuggled into Spain because volunteering had become illegal according to the terms of the Non-Intervention Policy.

As Baxell writes, some volunteers came by sea, jumping ship at Republican ports such as Barcelona and Valencia, facing torpedoes from Italian submarines in the Mediterranean. A few travelled in style – Percy Ludwick was recruited in Moscow and flown into Spain, and nurse Patience Darton was also jetted in at speed.

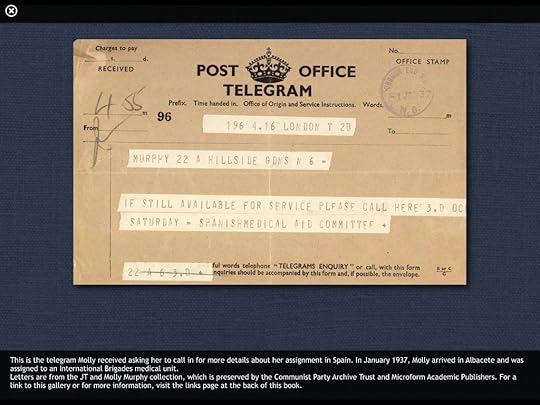

Typically, medical staff had little notice. Molly Murphy, whose letters feature in the multitouch iBook edition of A World Between Us , said the appeal for nurses ‘rang a bell in my heart‘. She felt it would be ‘nauseating’ to continue the private nursing she was doing ‘when splendid young men were dying on the international battlefields of Spain because there were so few nurses and doctors to help keep them alive.’ But soon after being accepted, she was told that no more medical personnel were needed in Spain. Then the telegram arrived:

Juggling the demands of pace, excitement and credibility is quite a challenge when you’re writing for a younger audience. Of course, one of the great advantages of teenage heroes and heroines is that they are at just the age when risk-taking is the norm. Who hasn’t had a good few ‘Did-I-really-do-that?’ moments in their own teenage past? But not many are likely to match the unbelievable spontaneity of so many of the volunteers who rallied to the cause of Spain in the 1930s.

Find out more about the real volunteers who supported the Republican Government in Spain in the 1930s in Richard Baxell’s Unlikely Warriors: The British in the Spanish Civil War and the Struggle Against Fascism, (shortlisted for the Political History Book of the Year, 2013). Angela Jackson’s British Women in the Spanish Civil War was an important source for me while writing A World Between Us. Two more recent publications, Salud! British Volunteers in the Republican Medical Service During the Spanish Civil War, 1936-1939 by Linda Palfreeman and ‘In Spain with Orwell’: George Orwell and the Independent Labour Party Volunteers in the Spanish Civil War by Christopher Hall, offer new insights on these particular groups of volunteers.

June 5, 2013

7th December 2013 75th Anniversary of British Battalion’s return

The British Battalion of the International Brigades arrived home 75 years ago, to be greeted by huge crowds at Victoria Station. Celebrate these heroes and heroines with the International Brigade Memorial Trust and Philosophy Football at No Pasaran! A Night to Remember! at Rich Mix, on Bethnal Green Road. Theatre, discussion, comedy, music and recitation.

Tickets are available from June and likely to sell out fast.

May 12, 2013

This is London

The first time I ever saw Tower Bridge open was thanks to my Great-Aunt Bertha. We had a huge number of great-aunts (my grandfather was almost at the end of thirteen children): Bertha was far-and-away our favourite. She told the most wonderful and subversive stories, often about her own childhood, including this particularly memorable tale of disobedience rewarded:

She was probably about thirteen or fourteen when she came up with a plan which meant she could take a day off school whenever she liked. She simply told her teacher that it was a Jewish ho liday. ”But none of the other girls will be away…” the bewildered mistress would say, to which Bertha replied, “Ah, that’s because they’re Ashkenazi. We’re Sephardi, you see.” And off she would go, exploring. Months passed, during which she discovered all sorts of nooks and crannies, and finally it came to at the end of year quiz. The subject was London. She got every question right, and walked off with the prize.

liday. ”But none of the other girls will be away…” the bewildered mistress would say, to which Bertha replied, “Ah, that’s because they’re Ashkenazi. We’re Sephardi, you see.” And off she would go, exploring. Months passed, during which she discovered all sorts of nooks and crannies, and finally it came to at the end of year quiz. The subject was London. She got every question right, and walked off with the prize.

My siblings and I loved it when Bertha came to babysit because she was the only person we knew who told us stories she had actually made up herself - bliss! Then one unforgettable day she told us the most amazing story of all, which lasted all day and was set in seventeenth-century London. As she told it, she took us to all the different places in the city where it happened, starting at St Bartholomew-the-Great in Smithfields, ending at the Houses of Parliament – and somehow contriving to pass by Tower Bridge on the way, just as it was opening.

I don’t think you could actually go up onto the bridge in those days,  but now you can, and this afternoon I took my two youngest children up there to see the suitably nostalgic new exhibition This is London. Miroslav Sasek‘s vibrant children’s guide to London and its ways was first published in 1958 and this display on the Tower Bridge walkway 43 metres above the Thames shows off his artwork in all its glory, highlighting continuity and change.

but now you can, and this afternoon I took my two youngest children up there to see the suitably nostalgic new exhibition This is London. Miroslav Sasek‘s vibrant children’s guide to London and its ways was first published in 1958 and this display on the Tower Bridge walkway 43 metres above the Thames shows off his artwork in all its glory, highlighting continuity and change.

Down in the  engineroom, once we’d admired the polish of the steam engines that used to drive the mechanism and got our heads round the meaning of the word ‘bascule’, we voted on our favourite of five works of London-inspired art produced by contemporary artists – this new exhibition, ‘Art at the Bridge‘, has been organised in collaboration with Southwark Arts Forum.

engineroom, once we’d admired the polish of the steam engines that used to drive the mechanism and got our heads round the meaning of the word ‘bascule’, we voted on our favourite of five works of London-inspired art produced by contemporary artists – this new exhibition, ‘Art at the Bridge‘, has been organised in collaboration with Southwark Arts Forum.

At the opposite end of Southwark, Artists’ Open House  was in full swing – over 200 artists in and around Dulwich are opening their doorsthis weekend and next.

was in full swing – over 200 artists in and around Dulwich are opening their doorsthis weekend and next.

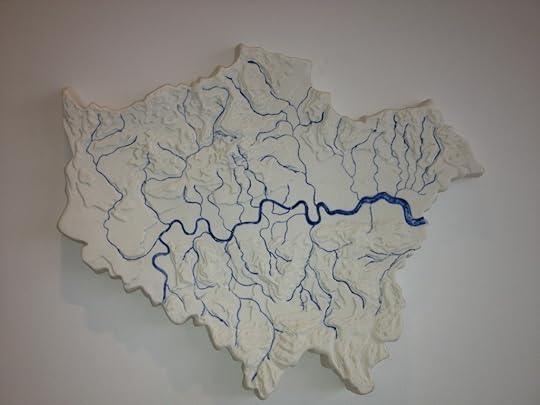

Here’s another view of the Shard from the window of Loraine Rutt in Honor Oak. Loraine’s interpretations of London bring together cartography and ceramics, and my photographs really don’t do her work justice, but they’ll give you an idea.

Created in the red clay out of which and on which much of the city is built, this piece shows the geography of a London stripped bare of its buildings:

Other use the translucence of porcelain, lit from behind, to evoke the fragility of the land.

Lost rivers of London are rediscovered….

Incidentally, if you’re interested in lost rivers, you’ll probably enjoy a new book called Silt Road, by Charles Rangeley-Wilson.)

I particularly love Loraine’s (very affordable) ‘Peckham postcards’:

(Loraine is also a brilliant teacher of ceramics, as my twins and their groaning shelves of artwork will testify…after-school lessons take place in her studio just below Peckham Rye Station. See her website for more information.)

May 6, 2013

2nd-3rd September 2013: Politeness & Prurience Conference, Edinburgh

I’ll be giving a paper called

‘Dr Graham’s ocular turn: a look at the origins of the Celestial Bed’

at

POLITENESS & PRURIENCE: SITUATING TRANSGRESSIVE SEXUALITIES IN THE LONG EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

It’s an international and multidisciplinary conference hosted by the History of Art Department at the University of Edinburgh. Find out more at the conference website.