John Allore's Blog

April 7, 2023

Farewell to John Allore

It is with great sadness that we share the news that John passed away on Thursday, March 30, 2023 after being struck by a car on his morning bike ride.

John devoted his life to the pursuit of solving the murder of his sister Theresa and to helping the families of missing and murdered women find out what happened to their loved ones and seek justice.

John was a devoted father to his three daughters and active in his community as Budget Director of the City of Durham.

We, the families and friends of the missing and murdered, owe him a great debt of gratitude for all his dedication, courage and valuable research. His passing leaves an unfillable void as his work will not be able to continue without him.

Thank you, John, for all that you’ve done. Our hearts go with you on this final voyage. At last you will be reunited with your sister.

Our heartfelt condolences go out to John’s beloved daughters, his family, and his friends. He will be sorely missed by all.

C’est avec beaucoup de regret que nous vous annonçons le décès de John, jeudi le 30 mars 2023, à la suite d’un accident de la route survenu alors qu’il faisait sa promenade matinale en vélo.

John a consacré sa vie à résoudre le meurtre de sa sœur Theresa et à aider les familles des femmes disparues et assassinées à découvrir ce qui est arrivé à leurs proches et à demander justice.

John était un père dévoué à ses trois filles et actif dans sa communauté en tant que directeur du budget de la ville de Durham.

C’est avec beaucoup de reconnaissance que les familles et amis des personnes disparues et assassinées lui expriment leurs plus sincères remerciements pour son dévouement, son courage et le temps précieux qu’il a consacré à son travail de recherche. Son départ laisse un grand vide, car son œuvre ne pourra continuer sans lui.

Merci pour tout, John. Nos cœurs t’accompagnent dans ce dernier voyage. Enfin, tu seras réuni avec ta sœur. Nous offrons nos plus sincères condoléances aux filles de John ainsi qu’à sa famille et ses proches. Il nous manquera à tous.

March 31, 2023

Solving for X

I have some follow-up thoughts on the 1985 murder of Francine Da Sylva, but in order to get there, I need to revisit two other unsolved murders we’ve covered: the 1979 death of Nicole Gaudreault and the 1975 strangulation and incineration of Diane Thibeault. Solving for x involves bringing an unknown variable to one side, then seeing how other elements line up with that variable – that’s what we’re going to do here – move and reconsider some variables.

Diane Thibeault

Diane ThibeaultThibeault was found in a vacant lot at the corner of St. Dominique Street and Dorchester Boulevard in downtown Montreal. Riding past on his bicycle at 4:30 in the morning, 16-year-old Jean Brisson noticed a fire in a vacant lot on Saturday morning, August 2, 1975. When he approached the fire, which was in danger of igniting a nearby abandoned house, he saw legs and immediately notified the police.

When Montreal police detectives Roy and Lemieux arrived, they found the still smoldering body of 25-year-old Diane Thibeault: dyed jet-black hair, pale skin, naked from the waist down, wearing a partially burned blue sweater with yellow stripes, with a piece of burning wood embedded in her vagina.

Thibeault had been beaten to death, strangled then set on fire. In his police report, Agent Roy noted, “The victim was sexually assaulted.” Thibeault was a denizen of The Main, a “Lower Depths” enclave of downtown Montreal known for drugs and prostitution. Near the body, police found a floppy hat, two scattered shoes, a comb, and a purse containing $26.40 in cash (the equivalent of more than $125 in today’s dollars). Thibeault was petite; 4 foot 9 inches, weighing approximately 82 pounds – her assailant could have manhandled her like a ragdoll.

According to the newspaper Allo Police, Thibeault frequented local “flop houses” and was known to hang out at the bars along Saint-Laurent: Chez Frafa, Capitol, Brasserie Alouette, and the Rialto. She had lots of “friends” along The Main. Given her lifestyle, police were none too aggressive in solving the murder. It wasn’t until three years later, in 1978, that they began to focus on a suspect.

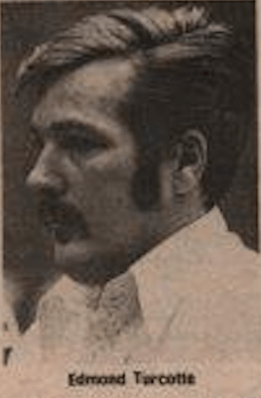

Roger Moreau

Roger MoreauRoger Moreau met Thibault at his mother’s rooming house four weeks before her death. His mother introduced Diane as her tenant. Coincidentally, three days later, Moreau was drinking with his brother-in-law, Edmond Turcotte, when Turcotte asked him if he knew Diane Thibeault because he got her pregnant and if he ever saw her again, he was going to give her a beating, “she’ll remember it for the rest of her life…” Shortly before her murder, Moreau observed Turcotte and Thibeault in a bar near Saint-Zotique Street. The two were drinking beer and making out, so he assumed the couple had reconciled.After the murder, when Moreau saw photos of Diane in Allo Police, he immediately called the police and said,” If you’re looking for Diane, look for Edmond Turcotte, ” then he hung up.

Allo Police

Allo PoliceLa Presse reporter Nicolas Berube covered the story in 2018. Berube interviewed former detective sergeant Jacques Duchesneau who was assigned to the case in 1975. Duchesneau later became Director of the Montreal Police, then Member of Parliament for Saint-Jérôme – Thibeault’s hometown – from 2012 to 2014. Asked to explain why it took the police three years to follow up on the lead, Duchesneau explained, “We were pretty busy …. “

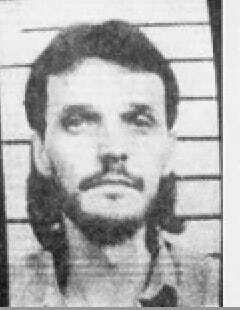

Edmond Turcotte was working as a cook at the New Spiro restaurant on Peel Street when police arrested him in November 1978. He was taken to the Sûreté du Québec headquarters on Parthenais Street and subjected to a polygraph test. After a lengthy interrogation, Turcotte confessed to the murder.

The Lodeo – photo courtesy Steve Knezevic

The Lodeo – photo courtesy Steve KnezevicTurcotte’s confession – lengthy and in grisly detail – is the subject of a podcast I also did in 2018 and was the basis for Berube’s La Presse story. For today, I’d like you to focus on dates and the geography of this case: the morning of the murder, August 2, 1975, Turcotte and Thibeault were drinking at Cabaret Rodéo on Saint-Laurent Boulevard. The Rodéo (later named Lodeo) was quite famous; it’s where Quebec playwright Michel Tremblay set his play about Montreal’s underbelly, Sainte Carmen of the Main, in 1976. The couple next moved to a rooming house near Saint Catherine Street. Turcotte then beat, raped, and strangled Diane Thibeault, but he did not leave her there. He dragged her half-dead to the vacant lot at St. Dominique and Dorchester, where he set her on fire and left her for dead.

As the case moved to trial, the police assumed they had a slam-dunk win on their hands. The coroner had ruled that “Diane Thibeault died a violent death on August 2, 1975, death for which you, Edmond Turcotte, must be held criminally responsible.” That’s not the way things turned out.

Edmond Turcotte

Edmond TurcotteTurcotte went to trial in late November 1978. La Presse tells us that his lawyer was a defense attorney named Réal Charbonneau: that’s sort of true. More on that later. Nicolas Berube spoke to Charbonneau on 2018. Incredibly, he was still practicing law. Charbonneau remembered the case and the “incredible chance” he experienced during the trial. The judge was André Biron, a good judge but a young judge. Though he does not directly say it, Charbonneau clearly felt Biron could be easily manipulated. Charbonneau was permitted to introduce the testimony of a psychiatrist who suggested that Edmond Turcotte was “slightly deficient” mentally. In doing so, Biron became convinced that Turcotte’s confession could not have been given voluntarily and would not admit it as evidence.

Charbonneau offered this final, cold assessment of the case’s dismissal:

“That’s it, life, huh? I do not think that the police put eight investigators to find another accused after that … He was acquitted, he was acquitted … If he had been another judge, who had not had that experience, he might have had a different attitude on the perception of facts. All this is chance. It is providence. “

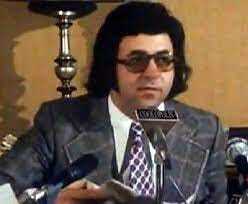

Réal Charbonneau

The La Presse reporter, Nicolas Berube, tried to track down Edmond Turcotte – who today would be seventy-four – by following his police record. Turcotte’s most recent offense was from 1997, a charge of theft in Joliette, for which the decision was withdrawn. At the time, Turcotte had been living in nearby Sainte-Julienne. When Berube visited Turcotte’s former residence, he found a well-kept mobile home and children’s toys but no Edmond Turcotte.

I think I know why Berube never found Edmond Turcotte. To understand that, you have to know more about Turcotte’s attorney Réal Charbonneau.

Réal Charbonneau

Réal CharbonneauEdmond Turcotte was not “slightly deficient.” He had enough of his mental faculties to hold down a job as a line cook. He could order drinks at a bar and turn on the charm with the ladies. He was not coerced into a confession as his lawyer Réal Charbonneau had suggested. To look at his confession transcript, Turcotte was ordered and methodical in his thoughts. He asked for a cup of coffee, so his police interrogators ordered coffee. And he was quite clear in his motive: Diane Thibeault was a “nothing” and a “cow” and, therefore, presumably deserved to die according to Turcotte’s chauvinistic worldview. The one thing police detectives didn’t do during Turcotte’s interrogation was allow him to see his lawyers—more than anything, that probably led to his acquittal.

Edmond Turcotte at trial

Edmond Turcotte at trialRéal Charbonneau’s career as a Montreal defense attorney was colorful, to say the least. In 1980 he was charged with contempt of court for failing to show up in court to represent his client, a man accused of the kidnapping and rape of a 13-year-old. Charbonneau alleged that the error was due to a mix-up between him and his legal associate, Frank Shoofey. Charbonneau and Shoofey often worked on cases together in this era, and in this instance, Shoofey decided that Charbonneau would represent the case of the pedophile on his own. The only problem was that Shoofey had failed to notify Charbonneau that he had abandoned him in this affair.

Frank Shoofey

Frank ShoofeyA word on Shoofey, who we’ve talked about before numerous times. Like one of his best friends, Jean-Pierre Rancourt, Shoofey was known as a mob lawyer (Rancourt writes a glowing chapter about his legal counterpart in his autobiography, Les Confessions d’un Criminaliste). Less known for his work as a negotiator in the recovery of Brother Andre’s heart (we will be here all day if we go down the rabbit hole of creepy Quebec Catholicism), Shoofey famously represented Montreal gangster Richard Blass, later gunned down by Quebec police for the murder of Italian mobster, Paul Violi. On October 15, 1985, Shoofey himself was murdered in the hallway outside his fifth-floor law office at 1030 Cherrier across from Parc La Fontaine in the Plateau ( remember my heeding about dates and places). The other point to track here is that Shoofey and Charbonneau had a long association as legal comrades documented in the public record, over a decade from about 1975 until Shoofey’s murder in 1985.

In 1982 Charbonneau got in trouble again when he was banned from a coroner’s inquest by Roch Heroux, then failed to show up for his court appearance on obstruction of justice charges. What exactly Charbonneau did in that coroner’s inquest is unknown, but he was immediately the target of an arrest warrant. By 1984 the matter was settled with Charbonneau ordered to contribute $5,000 towards a center for drug addicts.

Remember when bikers’ bodies started popping up in the St. Lawrence River in 1985? Charbonneau was in the middle of that too. Charbonneau represented Laurent “L’Anglais” Viau and Guy “Brutus” Geoffrion, both gunned down in a Hells Angels clubhouse, a purging incident that would become infamously known as the Lennoxville Massacre. Among Charbonneau’s transgressions representing The Hells, he was accused of encouraging a client to sign a false affidavit about the bombing of an apartment building on de Maisonneuve Blvd. in 1984 that killed four people.

In 1987 Charbonneau was sentenced to 18 months in prison in the case of that apartment bombing. He appealed and, in 1993, was granted a new trial. By 1997 Charbonneau was acquitted and never served a day behind bars. In 2003 Réal Charbonneau was in the news again, tossed from a Hells Angels megatrial for repeatedly arguing with the judge. When he was called to trial for the contempt case, Charbonneau was again a no-show. The matter was finally sorted out in 2006 – by this time, Allison Hanes doing the reporting for The Gazette – with Charbonneau slapped with a rebuke by the Quebec bar association.

———————

In 1986, The Gazette’s William Marsden interviewed another noted criminal lawyer, Sydney Leithman, who at the time was becoming the heir apparent to the then recently gunned-down Frank Shoofey. Among Leithman’s clients were Italian mob kingpin Frank Cotroni, the East End Gang’s Claude Dubois, and West End Gang leader Billy MacAllister. Leithman told Marsden how he started building his business representing clients in “whorehouses and gambling establishments.” In Leithman’s words, “The small little client today can provide you with the big case tomorrow.”

It begs the question that Leithman sort of answers: why do guys like Charbonneau represent apparent “lowlifes” like Edmond Turcotte (or, for that matter, Jean-Pierre Rancourt representing Fernand Laplante)? Because they know they are connected to money. Leithman was once asked to take on a client who did not appear well-healed, so he inquired of a police source, “Do you think this guy has any money?” The police officer replied, “Well, Sydney, the charge is drug-dealing.”

Charbonneau and Leithman were cut from the same cloth. In fact, in the matter of the phony affidavit, Charbonneau claimed it was Leithman who drew up the document. Charbonneau would not have taken on a client like Edmond Turcotte if he were just some low-level petty criminal who murdered a whorehouse prostitute. Charbonneau represented Turcotte because he was connected to money and was more than likely an earner for some Montreal mob outfit.

————————-

A word about Francine Da Sylva. Because this story is ultimately about Francine Da Sylva. I can’t remember if it was in a podcast, but I’ve spoken many times about the area’s strong influence on me: where she lived and her murder was committed. The locus is Place Emilie Gamelin. That is in itself a focal point in Montreal: the main library, BAnQ, is located there. It’s also where the Berri-UQAM metro station is placed, one of the main terminals of the city’s subway system. Archambault’s is there but will be closing this spring – a bookstore that has been an institution in the city for at least half a decade; my nephew worked there for years, and I used to drop in and surprise him whenever I was in town. I didn’t know until recently that Place Dupuis – an indoor shopping court across the square known today more for a homeless and drug problem, was the original location of Dupuis Frères, one of Montreal’s most venerated department stores.

Francine Da Sylva

Francine Da SylvaI could go on and on. Place Emile Gamelin is like a magnet for me. I am compelled to stay in this area whenever I visit Montreal. One time, after dark, I went out photo-exploring and unknowingly shot a picture of Francine Da Sylva’s apartment on Rue Andre without even having known Francine had lived there – and it’s a very unassuming building. The bus station is north of the square: I used to hang out there as a kid, and so did Francine and her friends – anonymous to each other. Finally, I can’t tell you the number of hours I’ve spent in that library, BAnQ, staring at microfilm of old newspapers, looking for clues and meanings.

I believe without question that Edmond Turcotte murdered Diane Thibeault. There is such specificity in his confession, such defiance in his posturing in court. But the judge let him go. Why? I would argue that Edmond Turcotte was protected. He served a low-level purpose to organized crime, and they would come to his aid when he needed assistance. Not for everything, of course. There are petty crimes where Turcotte met with justice. But nothing ever like murder. Which I believe he continued to commit throughout his criminal career.

Place Emilie Gamelin, 1963

Place Emilie Gamelin, 1963In 1978, while living in LaSalle, Turcotte was charged with soliciting a prostitute. Réal Charbonneau also represented Turcotte in that process. In 1980 while living in Pointe Aux Trembles, he was charged with manslaughter, though he appears to have beaten the sentence. In 1981 while living in Terrebonne, he was handed a six-month sentence for minor infractions. There are almost 20 years where Turcotte does not appear to have been in trouble with the law. Then in 1997, Turcotte resurfaced in the Ste. Calixte area (biker territory), where he was charged with theft.

The legal process for the murder of Diane Thibault started in late November 1978 and dragged out all through the spring of 1979, with the judge’s final decision not delivered until May 14. Charbonneau and Turcotte stuck together all through that process. There would have been telephone conversations and meetings for almost half a year. Throughout this process, Turcotte was incarcerated in the Parthenais jail at the Surete du Quebec headquarters near the Jacques Cartier bridge. Then all at once, he was set free in mid-May 1979. Two and a half months later, Nicole Gaudreault was found murdered in an alleyway near the Plateau. But Gaudreault isn’t murdered on just any Montreal summer night; she’s found on August 3, 1979, exactly four years from the date of the murder of Diane Thibeault. Would Edmond Turcotte have celebrated his release from incarceration for the murder of Diane Thibeault by murdering another woman on the anniversary of Thibeault’s killing?

Gaudreault spent the evening of August 2 at a bar called Baltimore at the corner of Saint Hubert and Ontario. Like Thibeault, Gaudreault was severely beaten, then transported from a domicile to an open area. In Gaudreault’s case, this was an alley – really an abandoned lot and field – where she was left to die. Montreal Police hypothesized that either she was attacked on the street by a stranger between the Baltimore and her destination two blocks away on Rue Saint Andre, or her assailant had been drinking with her at Baltimore, and the two left the bar together. The second scenario matches Turcotte having partied with Thibeault at the Rodeo before taking her back to a rooming house and assaulting her.

Six years later, Francine Da Sylva was also on her way home after dark. Like Nicole Gaudreault, she too had been out that evening; she met a friend at La Fameux at Mount Royal and St. Denis, and the two parted ways at St. Denis and Duluth with Francine making her way on foot back to her apartment at St. Andre. St. Andre is the same street where police found Gaudreault’s blood and belongings the night she was murdered. Francine’s apartment was a mere two blocks from what is thought to have been the place where Nicole was attacked.

Francine didn’t make it back to St. Andre. In fact, at Sherbrooke and St. Andre, she continued on that main artery, overshooting St. Andre, perhaps because, at this point, she knew she was being followed, and she wanted to remain in the public view of the heavily-trafficked Sherbrooke. At Rue Saint Timothee, she is attacked. Francine is dragged into the alley behind the apartment building at 902 Sherbrooke Street East, where she is raped and stabbed repeatedly.

Early in the process, police focused on a suspect named Raymond Charette. When arrested, Charette had evidence of blood on his clothing. A second victim of an attack on the same day that Francine was murdered came forward and told police she was waiting for a bus on rue Mont-Royal when she was forced into a vehicle by a man with a knife, alleged to have been Charette. They drove around The Plateau for a while, and this Charette character eventually let her out of the vehicle. Charette was never charged with Da Sylva’s murder.

Over the years, others have offered theories about who might have murdered Francine Da Sylva. Kristian Gravenor from Coolopolis suggested to me that it could have been Agostino Ferreira, a Quebec serial killer convicted of the 1990 rape and murder of Claire Samson and Danielle Laplante. In 1995, he sexually assaulted two women in an apartment at Berri and Ontario, one block west of the Baltimore, where Nicole Gaudreault was last seen in August of 1979. But Ferreira doesn’t quite fit. There is an age problem here. He was born in 1964; he would have been 16 when Gaudreault was murdered; not out of the question, but not great either. My bigger issue is his m.o.. Ferreira committed his murders indoors; Thibeault, Gaudreault, and Da Sylva were all found outdoors.

It’s the same problem as when producers for Sur les traces d’un tueur en série appeared to suggest William Fyfe was responsible for all the downtown murders in Montreal in the ’70s, a bit like throwing a ubiquitous sleuthing blanket over everything. Fyfe’s m.o. was strictly: daytime, indoors, ruse entry, and usually older women. Whoever killed Thibeault, Gaudreault, and Da Sylva was a nightcrawler. Fyfe’s not our guy.

Frank Shoofey

Frank ShoofeyWho could be our guy is Edmond Turcotte. He is often in the right place at the right time. He confessed to a murder with a very similar m.o. to those of Gaudreault and Da Sylva – outdoors, encounters on streets, or in bars. Whoever killed Gaudreault did it on the anniversary date of Thibault’s murder, almost like a punctuation mark saying, ‘I got away with murder!‘ And Turcotte appeared to have gang or gangster-affiliated protection. He certainly had a high-powered lawyer at his side, a man who later rose to prominence as a defender of the Hells Angels in some of their most infamous cases in the province of Quebec. Turcotte rarely served time for his convictions; usually, he was given a slap-on-the-wrist fine, something a high-powered lawyer could manufacture. When we catch up with Turcotte nearly 20 years later, he’s living near Ste. Calixte, an area well known for Hells Angels inhabitants. There’s one more thing that makes Turcotte unique: he had an association with the assassinated ‘mob lawyer’ Frank Shoofey.

One of the most interesting things about Francine Da Sylva’s murder on October 18, 1985, is that three days earlier, Frank Shoofey was gunned down, on October 15, 1985. And not only that, Shoofey’s law office on the 5th floor of that apartment building on Rue Cherrrier is two blocks from the alley where Da Sylva was stabbed to death. Standing at the entrance to that alley on Saint Timothee, you can see the Shoofey building up the hill.

Alley entrance at Saint Timothee, Shoofey building in the background

Alley entrance at Saint Timothee, Shoofey building in the backgroundEdmond Turcotte knew Frank Shoofey. At his interrogation for the murder of Diane Thibeault on November 23, 1978, the first thing Turcotte tells the coroner and police is: “My lawyers are not here this morning. They are supposed to arrive this afternoon… Mr. Shoofey and Charbonneau…”

Turcotte – Shoofey coroner inquest document

Turcotte – Shoofey coroner inquest documentThis is the same thing that played out two years later, where Shoofey and Charbonneau initially shared a case, but Charbonneau eventually ended up holding the bag for Frank. Recall the case: Réal Charbonneau was charged with contempt of court for failing to show up in court to represent his client, a man accused of the kidnapping and rape of a 13-year-old. Charbonneau alleged that the error was due to a mix-up with his legal associate, Frank Shoofey. Charbonneau and Shoofey often worked on cases together in this era. The one problem was Shoofey had failed to notify Charbonneau that he had drawn the shortest straw in this affair. Something like that might have irked Charbonneau; in fact, it could have really pissed him off.

Over the years, there’s been a lot of speculation about the motive for Frank Shoofey’s assassination, and the consensus appears to be that it was a mob hit. Quebec crime writer Michel Auger has written that “it was likely mobsters… were the killers of Shoofey,” with Claude Grant, an attorney who articled under Frank, adding that the Montreal underworld had a contract out on Shoofey a year before the actual murder. It’s a little complicated, but at its heart, Shoofey had influence with the Hilton family (not the hoteliers, this was a family of boxers). The Hiltons were set to sign an agreement with American boxing promoter Don King. Shoofey publically advised against this, which put him in the crosshairs of Montreal mafia boss Frank Cotroni. Frank Cotroni, who was representing the Hiltons, wanted the deal with Don King to go through. Cotroni was on the verge of being extradited to Connecticut on charges of heroin trafficking. He needed the money to pay for his legal defense (and by the way, his lawyer was Sidney Leithman, who you’ve already met). Shoofey was becoming too much of a nuisance for Cotroni, so he put a contract out for Frank’s murder. There is also a theory that the hit on Shoofey had nothing to do with the Cotronis, but everyone agrees that it was a mob hit.

When a contract is issued, someone has to carry out that contract. And we’ve seen an example of how this was carried out in this era. In 1969, a Sherbrooke businessman wanted his partner in the Pat’s Fried Chicken franchise murdered, so he ordered a contract on Rolland Giguere to be carried out by a local hood named Yvan Charland. Charland then had two thugs, the brothers Regis and Jean Claude Lachance, allegedly execute that contract for $10,000. So if Frank Cotroni wanted someone murdered in 1985, he might do something similar. He’d order a contract for the murder of Frank Shoofey, and then someone would find a low-level guy to carry that out for $5,000 to $10,000. We’ve also seen how lawyers like Sidney Leithman were well acquainted with underworld figures and how the lawyer Réal Charbonneau was not above getting involved in criminal activities: he was sentenced for forging a false affidavit about the bombing of an apartment building on de Maisonneuve Blvd. in 1984 that killed four people, a document which he said Sidney Leithman drew up.

There’s an element of geographic profiling to this theory. It suggests that criminals habitually stick to familiar territory. Turcotte hunted in the area around Sherbrooke and St. Andre because he had dealings in this area as early as 1978, where one of his lawyers was officed. Then – possibly – he ended up assassinating that lawyer. This is not unlike the urban section around King and Wellington in Sherbrooke, Quebec. Regis Lachance, Johnny Charland, and Luc Gregoire lived in that area, also around 1978. It’s where they partied at the Moulin Rouge (like the Rodeo), where Gitanes and Atomes gang clubhouses were located, where some of them committed arsons, abductions, and murders. It’s also where the criminal courts are located. Like Turcotte periodically visiting Shoofey, Lachance, Charland, and Gregoire spent many days in court hearings in the same area where they committed their crimes.

—————–

There’s a nagging component that I’m omitting – possibly that I should omit – but it keeps tugging at my pant cuff: the phone calls.

There’s an odd theme of anonymous phone calls in this narrative. They probably mean nothing, but I’m nosey by nature, so here it is:

Turcotte’s brother-in-law, Roger Moreau, made an anonymous phone call to the police saying,” If you’re looking for Diane, look for Edmond Turcotte, ” then he hung up. There was also an anonymous call made in the Nicole Gaudreault murder. The caller stated, “I just killed a woman. You’ll find it in the vacant lot of rue Saint-Andre,” then hung up. I’m not done. The English language newspaper, The Gazette, received a call after the Shoofey murder where the caller explained, “I and my colleagues have just assassinated Frank Shoofey. Good riddance.” They also claimed affiliation with the “Red Army Liberation Front,” something everyone believes to be a ruse to through police off the trail of the real killer.

I guess I’m bringing this up because two years before the Gaudreault murder, someone called the police after the Montreal murder of Katherine Hawkes in 1977, saying almost the exact same thing as the Gaudreult call: he explained that he had killed a woman and told police where they could find the body (you can see that whole story here).

One final thought: I reached out to Réal Charbonneau for this story. He replied once, confirming his law office today is located in Old Montreal, then ignored all my subsequent emails and phone messages.

—————–

I suggest that someone got word to Edmond Turcotte that he could make some fast money by carrying out the contract killing of Frank Shoofey. The execution of a man he knew, he had most likely been to the office on Rue Cherrier on numerous occasions. He was familiar with the area. He possibly murdered Nicole Gaudreault in that vicinity in 1979, on the anniversary he murdered Diane Thibeault. And he was there again just three days after Shoofey’s murder when he most likely stabbed and sexually assaulted Francie Da Sylva. The values are Shoofey, Da Sylva, Guadreault and Thibault. Solving for x requires moving the Turcotte variable to the other side and seeing if the two sides add up.

Francine Da Sylva with her friends

Francine Da Sylva with her friendsBut solving for x has more significant implications. Do you recognize the pattern? Where x are Quebec unsolved murders? Then on the other side, we have all these broad themes, these variables: Biker and gang activity, police forces unwilling to go the distance to solve the murders, the destruction of case evidence, innocent women caught in the crosshairs of gang members’ extra-curricular activities. Lawyers cutting corners and cutting deals. Coroners making deals with lawyers. Weak, easily manipulated judges. We see it here with Turcotte = Da Sylva + Gaudreault + Thibault. We’ve seen it before. The murder of Teresa Martin and the involvement of bikers. The murder of Theresa Allore + Rolland Giguare + Carole Fecteau = Regis Lachance, also a gang member.

Unsolved Murders ≠ Justice.

All of this is speculation. But after decades, with Montreal police seemingly taking no interest in this criminal investigative affairs, speculation is a weapon of last resort – someone needs to lift a finger and least to try and bring some sense of resolution to these unsolved murders.

—————-

March 14, 2023

The Crime Lady

There’s an interesting article in the New York Review of Books on the true crime writer, Sarah Weinman. If you don’t know Weinman, she’s had a newsletter for years called The Crime Lady. In 2018 she published her first book, The Real Lolita: The Kidnapping of Sally Horner and the Novel That Scandalized the World. In his review, Peddling Darkness, John J. Lennon writes about Weinman’s latest book, Scoundrel: How a Convicted Murderer Persuaded the Women Who Loved Him, the Conservative Establishment, and the Courts to Set Him Free ( note to self: stay away from the wordy titles).

Scoundrel tells the tale of Edgar Smith, who in 1957 abducted and bludgeoned to death a 15-year-old girl. Smith confessed to the killing and was sitting on death row when a conservative angel appeared in the form of William F. Buckley. Despite his confession (Smith convinced himself that it was a sort of false memory), The National Review founder became convinced of Smith’s innocence and eventually finagled an early release after Smith had served a fourteen-plus-year sentence. You know the end of this story – it’s a Norman Mailer / Jack Henry Abbott folie à deux: Smith went on to murder again.

In his review, John J. Lennon is critical of Weinman, arguing there’s almost a perverse voyeurism to her writing:

“Her interest in crime and all its grisly details is not un-self-aware: in her editor’s note for an anthology called Unspeakable Acts: True Tales of Crime, Murder, Deceit, and Obsession, she acknowledges the “problems inherent to what I think of as the ‘true crime industrial complex,’ which turns crime and murder into entertainment for the masses.” With Scoundrel, she spins this yarn of human darkness nevertheless.”

Where have I heard this before? In the summer of 2020, Weinman wrote a piece for BuzzFeed, The Future Of True Crime Will Have To Be Different where she went through the laundry list of then recently unspeakable acts of injustice – George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Rayshard Brooks, and Ahmaud Arbery – instructing us all to do better:

Sarah Weinman

Sarah Weinman

“Changing the very nature of the stories that are published, produced, and marketed is paramount. Rethinking the concept of “entertainment,” and what narrative structure is supposed to accomplish, is critical.

Only then can the myths that underpin the true crime genre — where murder and sexiness are permanently decoupled, where the “Wikipedia Browns” aren’t parroting the police party line, where serial killers aren’t transformed into bogeymen, and where catharsis doesn’t come at the expense of Black bodies — be banished for good.”

At the time, I thought of calling her out on this BuzzFeed piece, but I had my own true crime book coming out that fall – the last thing I wanted was to pick a fight with one of the biggest gorillas perched upon the crime writing fence. Now it appears that in 2023, Weinman is doing no better (did this new standard not apply to her?), and Lennon picks up on this in his review of Scoundrel:

“Yet as the book proceeds, this attempt to bring her story in line with the language of antiracist criminal justice reform begins to feel forced, as though Weinman is pandering or trying to check an obligatory ethical box before telling a conventional true crime story.”

Lennon argues that Weinman always “positions herself as an advocate,” but her body of work has yet to tackle an in-depth investigation of the injustice of the legal system. He seems to suggest that Weinman must tackle some essential piece of social justice writing to stay relevant, to which I say, God forbid! For me, Weinman needs to do just the opposite: stop moralizing and focus on what she does best: research, investigation, and consistent crime writing.

John J. Lennon

John J. LennonI need to pause here and that John J. Lennon is a convicted murderer. When I went to zip off an email to Lennon thanking him for calling out what I believe to be an emerging problem in true crime, I found that I couldn’t contact him so easily. As a Federal inmate at the Sullivan Correctional Facility in Fallsburg, New York, the only way to reach Lennon is to send him a letter. In 2001, at twenty-four, John J. Lennon was convicted of shooting and killing a man on a Brooklyn street. He is inmate #04A0823, serving a twenty-eight-year sentence for the sale of drugs, unlicensed operation of a motor vehicle, criminal possession of a weapon, and second-degree murder. Lennon is scheduled for release in 2028.

I understand Lennon’s desire to position himself as an advocate on the other side of the justice equation, but isn’t that just another way of saying you’re trying to make yourself stand out in a very crowded field? Lennon is himself a crime writer with a new book coming out next year called, The Tragedy of True Crime. We’re all jockeying for position – do the hustle.

I believe Lennon goes a little too far in criticizing Weinman for writing Smith during his second term in prison and appearing to bait and belittle him. The “you should talk to me, you want to get your side of the story, right” card is a weapon every good investigative reporter holds in their arsenal; it is naïve to think we don’t resort to such psychological tricks. So Weinman was a little sneaky: I like sneaky. The only reason I haven’t yet played that card is that I haven’t been forced to do so. But I play the game of manipulation as well as anyone – you have to if you want to produce any semblance of truth. Because people don’t follow simple logic. Especially criminals; their cunning and deceptive. Behavior is complex: more than anything, that probably explains the thirst for true crime.

I do side with Lennon in his writing about exploitation in the true crime engine by the media. Lennon describes a suspicious moment when he was asked to participate in a television program called Inside, hosted by Chris Cuomo. Lennon thought the show was about inmates coping with incarceration, only to discover when the cameras were rolling that the full title was Inside Evil. Immediately came the stock questions asking him to retrace his steps the night of the murder. The resulting episode included all the lurid tropes: “close-ups of my mug shots; shadowy, slow-motion reenactments of the shooting; scary background music.” It’s what drove me to write in the last newsletter that I doubt I will ever work with Paula Zahn on her On The Case true crime program: That’s Infotainment! I know their paintbox: shaky cameras, scary music, things that go bump in the night. Above all, a host that will disempower victims of crime by trying to coax them into an artificial emotional breakdown, and a robust attaboy endorsement of law enforcement without scrutiny – I have no time for that nonsense.

Sarah Weinman doesn’t need to separate herself from the “Wikipedia Browns.” She’s a gifted writer who should stop apologizing for the lurid dominion that interests her and embrace it with relentless consistency. I like her writing a lot better when she’s The Crime Lady: Own it, Sarah!

I suspect some of this comes from egging on from the book industry. Publishers love to push writers into making their historical stories relevant to today’s issues. I once made a pitch for a project about my father, who was involved in Canada’s nuclear industry for his entire forty-year career. It was going to be a simple tale of how he touched all the Canadian nuclear flashpoints: Pickering, GE in Peterborough, Chalk River, and eventually, the construction of Point Lepreau in New Brunswick. But then it couldn’t just be that. I was asked to join the current nuclear debate and talk about everything from Chernobyl, nuclear as clean energy, the environmental crisis, the restarting of mothballed plants, and all sorts of current event crap about which I have no interest in writing. I have no desire to be a windy wonking parrot.

Readers are smart. They will recognize a moral message without you having to write it. Tim Tyson doesn’t need to tell us that Blood Done Sign My Name is more than just a book about a lynching in Oxford, North Carolina. Jessica McDiarmid’s Highway of Tears is powerful because she doesn’t extend her credit by telling us the plight of murdered and missing indigenous women and girls is bad: she documents.

I am prone to playing the moral card as much as anyone. And anytime I pull it, I think twice because it feels dishonest and opportunistic. I don’t need to add that baggage. I prefer to employ a soft advocacy; if you create an awareness of the justice problem, that should be enough—no need to bray about it. I’m the brother of a murder victim: that’s my calling card.

I recently sat down and interviewed one of Quebec’s most venerated crime journalists (no, it wasn’t Andre Cedilot). I’m going to paraphrase what he told me because it’s the opening quote from the book I’m working on, I don’t want to steal my own thunder:

“You don’t have to make a big moralizing speech. Just tell the truth!”

*******************

This post was suggested to me by Jack Todd of The Montreal Gazette who read the NY Review of Books piece, and thought it might be in my wheel house. Thanks, Jack.

February 28, 2023

Quebec police aren’t holding any cards

Earlier this month Quebec’s La Presse did an article on law enforcement’s use of genetic genealogy to assist in capturing criminals (if you don’t speak French, run it through a translator). It’s almost a daily occurence now that cold cases in the United States are solved using this technique. And these are old cases – 30 years, 40 years, 50 years. People are begin to question why Quebec has had a cold case unit for almost 20 years now and has yet to solve a crime (Guylaine Potvin does not count, that case hasn’t survived the acid test of a trial).

In the article I noted that Quebec police forces have “”thrown away, misplaced or destroyed” a number of objects containing DNA linked to crime scenes over the years, including murders, which could limit the scope of this technique for many files.”

La Presse continued:

“For example, the Sûreté du Québec in Sherbrooke told me that my sister’s underwear had been destroyed five years after the murder,” he says.

And his case is not isolated, adds Mr. Allore. “I’ve been doing this for 20 years, and I’ve spoken to so many families of victims who have been told the same thing. The DNA is no longer there to be analyzed,” says Allore, who also hosts the podcast Who Killed Theresa? which focuses on the unsolved murders in Quebec.

“I’m happy if it can help solve crimes, but I’m not holding my breath,” he said.”

This is nothing new, I’ve been saying it for years. Quebec police are playing poker in the game of genetic genealogy but not holding any cards.

A second article in La Presse quoted the Laboratory of Judicial Sciences and Legal Medicine of Quebec (LSJML) as being “hopeful” of new techniques, but then they hedged their response with an acknowledgement that the science was “quite complex.” The piece then went on to catalogue a host of techniques available in Quebec -genetic genealogy, phenotyping, DNA networks, PatronYme, Rapid DNA – but then failed to mention whether any of them were currently being deployed in the province. By this point, practically everyone is aware of these remedies, what’s important is are you using them! And of course, the elephant in the room, what was missing from this article is any mention of Quebec law enforcement endorsement of these techniques in conjunction with the LSJML. It’s a maddening game of three-card Monte where Quebec law enforcement continues to stall in their shirking accountability dance. But sooner or later the music will stop. And we’re going to know they’re not holding any cards.

To borrow a phrase from a scientist from another discipline who felt like he was chasing windmills, No one’s minding the store. They’re all asleep at the switch.

Policiers du Québec jouant au poker sans aucune carte

Plus tôt ce mois-ci, La Presse a publié un article sur l’utilisation par les forces de l’ordre de la généalogie génétique pour aider à capturer des criminels. C’est presque un événement quotidien maintenant que les cold case aux États-Unis sont résolus en utilisant cette technique. Et ce sont de vieux cas – 30 ans, 40 ans, 50 ans. Les gens commencent à se demander pourquoi le Québec a une unité de cold case depuis près de 20 ans maintenant et n’a pas encore résolu un crime (Guylaine Potvin ne compte pas, cette affaire n’a pas survécu à l’épreuve décisive d’un procès).

Dans l’article, j’ai noté que les corps policiers du Québec ont « jeté, égaré ou détruit » un certain nombre d’objets contenant de l’ADN liés à des scènes de crime au fil des ans, y compris des meurtres, ce qui pourrait limiter la portée de cette technique pour de nombreux dossiers. »

La Presse poursuit :

« Par exemple, la Sûreté du Québec à Sherbrooke m’a dit que les sous-vêtements de ma sœur avaient été détruits cinq ans après le meurtre, raconte-t-il.

Et son cas n’est pas isolé, ajoute M. Allore. “Cela fait 20 ans que je fais ça, et j’ai parlé à tellement de familles de victimes à qui on a dit la même chose. L’ADN n’est plus là pour être analysé”, explique Allore, qui anime également le podcast Who Killed Theresa? qui se concentre sur les meurtres non résolus au Québec.

“Je suis heureux si cela peut aider à résoudre des crimes, mais je ne retiens pas mon souffle”, a-t-il déclaré.”

Ce n’est pas nouveau, je le dis depuis des années. Les policiers du Québec jouent au poker dans le jeu de la généalogie génétique mais ne détiennent aucune carte.

Un deuxième article de La Presse citait le Laboratoire des sciences judiciaires et de médecine légale du Québec (LSJML) comme étant « plein d’espoir » dans les nouvelles techniques, mais ils ont ensuite couvert leur réponse en reconnaissant que la science était « assez complexe ». L’article a ensuite répertorié une foule de techniques disponibles au Québec – généalogie génétique, phénotypage, réseaux d’ADN, PatronYme, ADN rapide – mais a ensuite omis de mentionner si l’une d’entre elles était actuellement déployée dans la province. À ce stade, pratiquement tout le monde connaît ces remèdes, ce qui est important, c’est que vous les utilisiez ! Et bien sûr, l’éléphant dans la salle, ce qui manquait à cet article, c’est toute mention de l’approbation par les forces de l’ordre du Québec de ces techniques en collaboration avec le LSJML. C’est un jeu exaspérant de three-card Monte où les forces de l’ordre du Québec continuent de caler dans leur danse d’évitement de la responsabilité. Mais tôt ou tard la musique s’arrêtera. Et nous allons savoir qu’ils ne détiennent aucune carte.

Pour reprendre une phrase d’un scientifique d’une autre discipline qui avait l’impression de chasser des moulins à vent, “No one’s minding the store. They’re all asleep at the switch.”

February 21, 2023

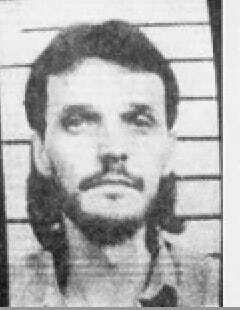

COMPOSITE: Luc Gregoire

Last week the podcast Crime Junkie put my sister’s unsolved murder back up for discussion with their episode, CONSPIRACY: Theresa Allore. The program brought close to 4,000 daily hits to Who Killed Theresa, a lot for a website about Quebec crime. I want to associate myself with everything in that podcast; it’s excellent and factually accurate. I found their investigative efforts inspiring. I was particularly interested in the hosts’ discussion about a composite drawing made in the early 1980s by the survivor of a sexual assault in the Eastern Townships (the “Female Jogger Attacked” composite made by the survivor, who was both an accomplished athlete and an artist). The picture bears a striking resemblance to a man named Luc Gregoire. Gregoire grew up in the Townships and had a history of arrests for assaults and burglaries in the Sherbrooke area. In 1977 he enlisted in the Canadian military, doing his training in Saint Jean sur Richelieu, where in the fall of that year, Denise Basinet was found strangled and dumped near a highway off-ramp. Gregoire soon moved to Alberta and was eventually convicted of the 1993 murder of a Calgary 7-11 clerk, Lailanie Sylva. Gregoire died while serving a life sentence in Archambault prison in 2015. To this day, the Calgary Police suspect Luc Gregoire of having committed several downtown murders of sex trade workers.

Ashley and Brit discuss the composite on Crime Junkie. Brit describes a man with thick dark brows, a ducktail beard, and “hair kinda like a bowl cut.” Then Brit describes viewing the composite next to a photo of Luc Gregoire:

You can judge for yourself, but I don’t believe Brit and Ashley’s response is unjustified:

Female Jogger Attacked composite and photo of Luc Gregoire

Female Jogger Attacked composite and photo of Luc GregoireIt’s a little like the visual pun in Charles Allan Gilbert’s All is Vanity, or those picture book games, which one is different where you work to strengthen visual discrimination skills. You know, where you have to look closely at a set of pictures of chickens or Alexander Hamilton to finally see that one of the chickens has a third toe or Hamilton has a spot on his brow. It’s a very subjective exercise; the eye sees what it wants to see, that’s the nature of cognitive blind spots.

Which Hamilton is different?

Which Hamilton is different?For instance, here’s a picture of another man who also looks like the sexual attacker composite. And this isn’t just any man, this is Robert Leblanc. Like Gregoire, Leblanc was convicted of only one murder, the 1992 strangulation death of 22-year-old Montrealer Chantal Brochu. Also, like Gregoire, Leblanc had a prior history of sexual assaults, but not in Montreal, in Sherbrooke – the same place and at the same time where the sexual assaults and unsolved murders occurred in the Eastern Townships. The Female Jogger Attacked composite could also be a portrait of Robert Leblanc.

Robert Leblanc

Robert LeblancTo confuse things further, the Female Jogger Attacked victim was such an accomplished artist that she made another drawing. This second composite ran in the local Eastern Townships newspapers the week after the first composite. She is describing the same attacker, but this second picture looks less like Gregoire and more like Robert Leblanc:

The second Female Jogger Attacked composite

The second Female Jogger Attacked compositeAfter all that, I will say that in my opinion, this is probably not Robert Lablanc. From what we know, Leblanc never owned a car. In planning his murder of Chantal Brochu, Leblanc took a bus from downtown Sherbrooke to Montreal. He then proceeded to a bar where he knew there would be a lot of beautiful, single woman. After the murder, he hitchhiked back to Sherbrooke. Luc Gregoire was known to use cars in most of his sexual assaults. And the jogger who was attacked near Sherbrooke described being dragged back to a car when the man proceeded to sexually assault her.

Here’s where it gets even trickier. Because there’s still yet another composite. This is something I’ve been sitting on for years. We tried to fit it into Wish You Were Here, but the publisher decided we were too close to the release date, and inserting the photo and story might confuse readers.

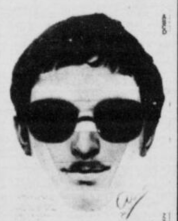

The 1977 La Patrie composite

The 1977 La Patrie compositeThis is a composite from La Patrie, a weekly Montreal newspaper that ran from 1957 to 1978. In the summer of 1977, La Patrie published this composite, asking for the public’s assistance in tracking down a man wanted for attempted murder. The man was described as being between 25-30 years of age, white, about 5’11” with brown eyes and hair, and weighing approximately 150 pounds. He spoke French and wore sunglasses. The notice asked that the public phone a detective D. Lauzon. And from the number left, we know Detective Lauzon worked for the Montreal Urban Community Police (CUM), what today is known as the SPVM, or just the Montreal police force.

Despite the age being wrong – Luc Gregoire was only 17 in 1977 – everything else is uncanny: dark hair, ducktail beard, kind of a bowl cut. We can’t see his brows because of the sunglasses. But it looks very much like a young, slight Luc Gregoire. Here’s the kicker. When Gregoire was finally arrested in 1993 for the murder of Lanie Sylva, police described him as wearing army fatigue pants (many Township sexual assault survivors described their attacker as wearing combat gear) and large, oversized sunglasses.

Of particular interest is the run date of the composite: July 17, 1977. The summer of 1977 was clustered with sexual assaults, disappearances, and murders in the vicinity of Montreal, none more so than the unsolved murders of Johanne Dorion and Chantal Tremblay. Both disappeared less than ten days after the running of the composite drawing on July 29, 1977. Tremblay was last seen getting off a bus at a Montreal metro station. Dorion worked in Montreal near that metro station and was last seen getting off a bus near her home in Laval. She was found ten days later strangled near the St. Lawrence River. Tremblay’s remains were found almost two years later in a wooded area owned by the Department of National Defence.

The first Townships murder for which Gregoire is a potential suspect (possibly committed with the assistance of an older partner, the folie à deux theory) is the March 1977 death of Louise Camirand. The 24-year-old who served with the Quebec military unit, The Sherbrooke Hussars, was strangled with a military boot lace. It is very possible that the Montreal Police were looking for a sexual predator in Montreal who was Luc Gregoire, and that Gregoire was shuttling between Montreal and Sherbrooke in 1977-78, committing a series of sexual assaults and murders in this corridor, most of which remain unsolved to this day.

If you’re thinking Gregoire too young for such a violent pedigree, a reminder that Richard Bouillon – who confessed to the murder of Julie Surprenant – had committed over a dozen sexual assaults before he reached the age of sixteen. Also, Gregoire traveled between Montreal and Sherbrooke; he was eventually stationed at CFB Petawawa and would have had to pass through the urban city on trips home to visit his family. Finally, Gregoire had a record of assaults in Montreal, but those didn’t occur until later. In 1983 he was paroled to a community residential centre in the city, where he quickly found himself in trouble again, arrested for assaulting a sex trade worker.

So the La Patrie composite is Luc Gregoire, right? Maybe.

I decided to do one last scan of the newspaper archives to see if I could learn anything more about this attacker who preyed on Montreal in the summer of 1977. Sure enough, the journal Montreal Matin had the goods. Ten days earlier, the Montreal daily ran a story on the attempted murder suspect. At around one in the afternoon, the young man gained entry to the home of a 63-year-old woman in Ville Saint-Laurent by pretending to be an employee of Gulf Oil. After surveilling the residence, he pulled a revolver and announced he had come to kill her. He then took a dog leash and began strangling her. The woman lost consciousness, and the man left her for dead but did not rob or sexually assault her. The notice again describes a man between 25 and 30, 5’11”, about 150 pounds, and French-speaking.

1977 Montreal Matin composite

1977 Montreal Matin compositeApart from the sunglasses, it is the same man from the La Patrie article, except that the artist has removed the sunglasses, which leads me to believe the attacker left his glasses on, but police removed them in the Montreal Matin composite to assist the public with identification. This means no one knows precisely what the 63-year-old woman’s attacker’s eyes were like. These eyes are open, direct, and clear. In the few photos we have, Gregoire’s eyes always appear less alert and squinty.

Interestingly the attack occurred in Ville St. Laurent. Two months later, Katherine Hawkes was murdered in the same Montreal neighborhood. But the m.o. is off. Gregoire was not known for fooling sexagenarians to gain entry into their homes and then attacking them in the middle of the afternoon. It sounds more like William Fyfe. But it doesn’t look like William Fyfe. Gregoire occasionally attacked in interiors, as opposed to outdoor spaces, and he used guns in some of his assaults.

Is it Gregoire? The eyes see what they want to see. If Gregoire was criminally active on the island of Montreal as early as 1977, it casts a whole new perspective on a catalog of the city’s unsolved murders.

LE COMPOSITE: Luc Gregoire

La semaine dernière, le podcast Crime Junkie a remis le meurtre non résolu de ma sœur en discussion avec leur épisode, CONSPIRACY: Theresa Allore. L’émission a rapporté près de 4 000 visites quotidiennes à Who Killed Theresa, beaucoup pour un site Web sur la criminalité au Québec. Je veux m’associer à tout dans ce podcast ; c’est excellent et factuellement précis. J’ai trouvé leurs efforts d’enquête inspirants. J’ai été particulièrement intéressé par la discussion des animatrices sur un dessin composite réalisé au début des années 1980 par la survivante d’une agression sexuelle dans les Cantons-de-l’Est (le composite « Female Jogger Attacked» réalisé par la survivante, qui était à la fois une athlète accomplie et une artiste). La photo a une ressemblance frappante avec un homme du nom de Luc Grégoire. Grégoire a grandi dans les Cantons-de-l’Est et a eu un historique d’arrestations pour voies de fait et cambriolages dans la région de Sherbrooke. En 1977, il s’est enrôlé dans l’armée canadienne, faisant sa formation à Saint Jean sur Richelieu, où à l’automne de cette année-là, Denise Basinet a été retrouvée étranglée et jetée près d’une bretelle de sortie d’autoroute. Gregoire a rapidement déménagé en Alberta et a finalement été reconnu coupable du meurtre en 1993 d’un commis du Calgary 7-11, Lailanie Sylva. Grégoire est décédé en purgeant une peine d’emprisonnement à perpétuité à la prison Archambault en 2015. À ce jour, la police de Calgary soupçonne Luc Grégoire d’avoir commis plusieurs meurtres au centre-ville de travailleuses du sexe.

Ashley et Brit discutent du composite sur Crime Junkie. Brit décrit un homme avec des sourcils épais et foncés, une barbe en queue de canard et “des cheveux un peu comme une coupe au bol”. Puis Brit décrit la visualisation du composite à côté d’une photo de Luc Grégoire :

Vous pouvez en juger par vous-même, mais je ne pense pas que la réponse de Brit et Ashley soit injustifiée:

Female Jogger Attacked composite and photo of Luc Gregoire

Female Jogger Attacked composite and photo of Luc GregoireC’est un peu comme le jeu de mots visuel dans All is Vanity de Charles Allan Gilbert, ou ces jeux de livres d’images, dont l’un est différent. Vous savez, où vous devez regarder de près une série de photos de poulets ou du président Alexander Hamilton pour finalement voir que l’un des poulets a un troisième orteil ou Hamilton a une tache sur son front. C’est un exercice très subjectif; l’œil voit ce qu’il veut voir, c’est la nature des angles morts cognitifs.

Quel Hamilton est différent?

Quel Hamilton est différent?Par exemple, voici une photo d’un autre homme qui ressemble également au composite de l’agresseur sexuel. Et ce n’est pas n’importe quel homme, c’est Robert Leblanc. Comme Grégoire, Leblanc a été reconnu coupable d’un seul meurtre, la mort par strangulation en 1992 de la Montréalaise de 22 ans Chantal Brochu. De plus, comme Grégoire, Leblanc avait des antécédents d’agressions sexuelles, mais pas à Montréal, à Sherbrooke – au même endroit et au même moment que les agressions sexuelles et les meurtres non résolus se sont produits dans les Cantons-de-l’Est. Le composite Female Jogger Attacked pourrait aussi être un portrait de Robert Leblanc.

Robert Leblanc

Robert LeblancPour compliquer encore les choses, la victime de la Female Jogger Attcked était une artiste tellement accomplie qu’elle a fait un autre dessin. Ce deuxième composite a été publié dans les journaux locaux des Cantons-de-l’Est la semaine suivant le premier composite. Elle décrit le même agresseur, mais cette deuxième photo ressemble moins à Grégoire et plus à Robert Leblanc :

The second Female Jogger Attacked composite

The second Female Jogger Attacked compositeAprès tout ça, je dirai qu’à mon avis, ce n’est probablement pas Robert Lablanc. D’après ce que nous savons, Leblanc n’a jamais possédé de voiture. En planifiant son meurtre de Chantal Brochu, Leblanc a pris un autobus du centre-ville de Sherbrooke à Montréal. Il s’est ensuite rendu dans un bar où il savait qu’il y aurait beaucoup de belles femmes célibataires. Après le meurtre, il est retourné à Sherbrooke en auto-stop. Luc Grégoire était connu pour avoir utilisé des voitures dans la plupart de ses agressions sexuelles. Et la joggeuse qui a été attaquée près de Sherbrooke a raconté avoir été ramenée dans une voiture lorsque l’homme a commencé à l’agresser sexuellement.

C’est là que ça devient encore plus compliqué. Parce qu’il y a encore un autre composite. C’est quelque chose sur lequel je suis assis depuis des années. Nous avons essayé de l’intégrer dans Wish You Were Here, mais l’éditeur a décidé que nous étions trop proches de la date de sortie, et l’insertion de la photo et de l’histoire pourrait dérouter les lecteurs.

The 1977 La Patrie composite

The 1977 La Patrie compositeIl s’agit d’un composite de La Patrie, un hebdomadaire montréalais qui a paru de 1957 à 1978. À l’été 1977, La Patrie a publié ce composite, demandant l’aide du public pour retrouver un homme recherché pour tentative de meurtre. L’homme a été décrit comme étant âgé de 25 à 30 ans, blanc, mesurant environ 5 pi 11 po avec les yeux et les cheveux bruns et pesant environ 150 livres. Il parlait français et portait des lunettes de soleil. L’avis demandait que le public téléphone à un détective D. Lauzon. Et d’après le nombre à gauche, nous savons que le détective Lauzon travaillait pour la Police de la communauté urbaine de Montréal (CUM), ce qu’on appelle aujourd’hui le SPVM, ou tout simplement la police de Montréal.

Bien que l’âge soit faux – Luc Grégoire n’a que 17 ans en 1977 – tout le reste est étrange : cheveux noirs, barbe en queue de canard, coupe au bol. On ne voit pas ses sourcils à cause des lunettes de soleil. Mais il ressemble beaucoup à un jeune et léger Luc Grégoire. Voici le coup de pied. Lorsque Grégoire a finalement été arrêté en 1993 pour le meurtre de Lanie Sylva, la police l’a décrit comme portant un pantalon de survêtement de l’armée (de nombreux survivants d’agressions sexuelles du canton ont décrit leur agresseur comme portant un équipement de combat) et de grandes lunettes de soleil surdimensionnées.

La date d’exécution du composite est particulièrement intéressante : le 17 juillet 1977. L’été 1977 a été marqué par des agressions sexuelles, des disparitions et des meurtres dans les environs de Montréal, rien de plus que les meurtres non résolus de Johanne Dorion et Chantal Tremblay. Tous deux ont disparu moins de dix jours après la diffusion du dessin composite le 29 juillet 1977. Tremblay a été vu pour la dernière fois en train de descendre d’un autobus à une station de métro de Montréal. Dorion travaillait à Montréal près de cette station de métro et a été vue pour la dernière fois en train de descendre d’un autobus près de chez elle à Laval. Elle a été retrouvée dix jours plus tard étranglée près du fleuve Saint-Laurent. La dépouille de Tremblay a été retrouvée près de deux ans plus tard dans un boisé appartenant au ministère de la Défense nationale.

Le premier meurtre dans les Cantons pour lequel Grégoire est un suspect potentiel (possiblement commis avec l’aide d’un partenaire plus âgé, la théorie de la folie à deux) est la mort en mars 1977 de Louise Camirand. Le jeune homme de 24 ans qui a servi dans l’unité militaire québécoise, The Sherbrooke Hussars, a été étranglé avec un lacet de botte militaire. Il est fort possible que la Police de Montréal recherchait un prédateur sexuel à Montréal qui était Luc Grégoire, et que Grégoire faisait la navette entre Montréal et Sherbrooke en 1977-78, commettant une série d’agressions sexuelles et de meurtres dans ce corridor, dont la plupart restent non résolus à ce jour.

Si vous pensez que Grégoire est trop jeune pour un pedigree aussi violent, rappelons que Richard Bouillon – qui a avoué le meurtre de Julie Surprenant – avait commis plus d’une dizaine d’agressions sexuelles avant d’avoir atteint l’âge de seize ans. De plus, Grégoire a voyagé entre Montréal et Sherbrooke; il a finalement été affecté à La Garnison Militaire Petawawa et aurait dû traverser la ville urbaine lors de voyages chez lui pour rendre visite à sa famille. Enfin, Grégoire avait un dossier d’agressions à Montréal, mais celles-ci ne se sont produites que plus tard. En 1983, il a été mis en liberté conditionnelle dans un centre résidentiel communautaire de la ville, où il s’est rapidement retrouvé en difficulté, arrêté pour avoir agressé une travailleuse du sexe.

Alors le composite de La Patrie est Luc Grégoire, n’est-ce pas ? Peut être.

J’ai décidé de faire un dernier balayage des archives du journal pour voir si je pouvais en savoir plus sur cet assaillant qui a attaqué Montréal à l’été 1977. Effectivement, le journal Montréal Matin avait la marchandise. Dix jours plus tôt, le quotidien montréalais avait publié un article sur le suspect de tentative de meurtre. Vers une heure de l’après-midi, le jeune homme s’est introduit chez une femme de 63 ans à Ville Saint-Laurent en se faisant passer pour un employé de Gulf Oil. Après avoir surveillé la résidence, il a sorti un revolver et a annoncé qu’il était venu pour la tuer. Il a ensuite pris une laisse de chien et a commencé à l’étrangler. La femme a perdu connaissance et l’homme l’a laissée pour morte mais ne l’a pas volée ni agressée sexuellement. L’avis décrit à nouveau un homme entre 25 et 30 ans, 5’11”, environ 150 livres, et francophone.

1977 Montreal Matin composite

1977 Montreal Matin composite

À part les lunettes de soleil, c’est le même homme de l’article de La Patrie, sauf que l’artiste a retiré les lunettes de soleil, ce qui me porte à croire que l’agresseur a laissé ses lunettes, mais la police les a retirées dans le composite Montréal Matin pour aider le public avec pièce d’identité. Cela signifie que personne ne sait exactement à quoi ressemblaient les yeux de l’agresseur de la femme de 63 ans. Ces yeux sont ouverts, directs et clairs. Sur les quelques photos dont nous disposons, les yeux de Grégoire apparaissent toujours moins alertes et plissés.

Fait intéressant, l’attaque s’est produite à Ville Saint-Laurent. Deux mois plus tard, Katherine Hawkes est assassinée dans le même quartier montréalais. Mais le m.o. est éteint. Grégoire n’était pas connu pour tromper les sexagénaires pour entrer chez eux et les attaquer ensuite en milieu d’après-midi. Cela ressemble plus à William Fyfe. Mais cela ne ressemble pas à William Fyfe. Grégoire a parfois attaqué dans des intérieurs, par opposition à des espaces extérieurs, et il a utilisé des armes à feu dans certaines de ses agressions.

Est-ce Luc Grégoire ? Les yeux voient ce qu’ils veulent voir. Si Grégoire était criminel sur l’île de Montréal dès 1977, cela jette une toute nouvelle perspective sur un catalogue des meurtres non résolus de la ville.

February 14, 2023

Puzzle 15

Have you heard of Puzzle 15?

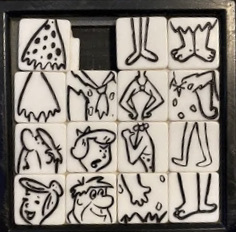

I bet you have, you just don’t know it. You know those 4 x 4 tile scrambles where you have to rearrange the sliding pieces into an image? Popeye? The Flinstones? That’s the 15 puzzle, sometimes called Gem, Boss, or Mystic Square.

The 15 puzzle

The 15 puzzleThe 15 puzzle was the original fidget spinner occupying busy digits a century before the iPhone. The origin of Puzzle 15 is something of a puzzle itself. It became a craze in the 1880s. Game huckster Sam Lloyd said he invented it. He didn’t. In 2006 Jerry Slocum and Dic Sonneveld published an entire book – not about games in general, but specifically the 15 Puzzle – in which they unscrambled some of its mysteries:

“Sam Loyd did not invent the 15 puzzle and had nothing to do with promoting or popularizing it. The puzzle craze that was created by the 15 Puzzle began in January 1880 in the U.S. and in April in Europe. The craze ended by July 1880 and Sam Loyd’s first article about the puzzle was not published until sixteen years later, January 1896. Loyd first claimed in 1891 that he invented the puzzle, and he continued until his death a 20 year campaign to falsely take credit for the puzzle. The actual inventor was Noyes Chapman, the Postmaster of Canastota, New York, and he applied for a patent in March 1880.”

I conducted a not-too-scientific lit review of the facts in this passage. I cannot locate any claim by Loyd in 1891, nor the article from 1896. And Noyes Chapman’s patent application will have to remain another lingering mystery – there’s no record of it. However, a Noyes S. Chapman was confirmed in a senate executive session in 1867 as postmaster of Canastota, New York.

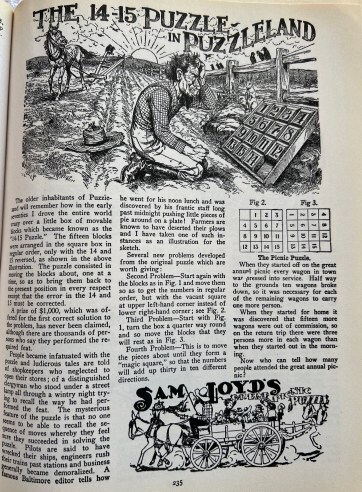

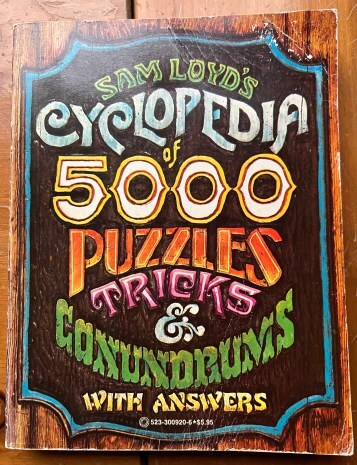

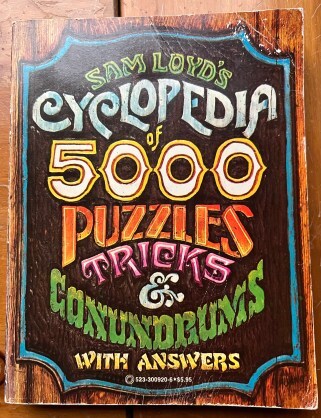

Sam Loyd’s Cyclopedia of 5000 Puzzles, Tricks & Conundrums (with answers)

Sam Loyd’s Cyclopedia of 5000 Puzzles, Tricks & Conundrums (with answers)Certainly, by the time he authored his 1914 masterpiece, “Sam Loyd’s Cyclopedia of 5000 Puzzles, Tricks & Conundrums (with answers),” Loyd was taking credit for the 15 Puzzle invention:

“The older inhabitants of Puzzleland will remember how in the early seventies I drove the entire world crazy over a little box of movable pieces which became known as the “14-15 Puzzle”. The fifteen pieces were arranged in the square box in regular order, only with the 14 and 15 reversed, as shown in the figure. The puzzle consisted in moving the pieces about, one at a time, so as to bring them back in the present position in every respect except that the error in the 14 and 15 must be corrected. A prize of $1000, which was offered for the first correct solution to the problem has never been claimed.”

Master Sam Loyd

Master Sam LoydThe problem is there is no mention of the 14-15 Puzzle “in the early seventies.” It first came up in January 1880, and how the fidget wonder “excites” the public. By March 15 Puzzle mania was in full bloom, with The Atlanta Constitution reporting how “The great 13, 14, 15 puzzle game is racing the brains of thousands, causing neuralgia and headache”. Loyd wasn’t associated with the frenzy until 1893 when Connecticut’s The Press reported Sam Loyd as “famous as being the author of “Pigs in Clover” and the “15 Puzzle”.

Flintstones jumble

Flintstones jumbleSome have likened 15 Puzzle hysteria to the Rubik’s Cube phenom in the 1980s. It’s an apt comparison, as the Rubik’s Cube is sort of a 3-D version of Puzzle 15. In fact, it’s kind of like what would happen if you combined a 2-D math puzzle with the 3-D block game Soma. Very recently, a British American mathematician, Henry Segerman, took this one step further and created Continental Drift, a Rubik’s Cube in the shape of the earth. It’s the same idea as taking numbers and associating them with a picture of the Flintstones and the Rubbles. In 1972, U.S. Chess Grandmaster Bobby Fischer appeared on The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson and solved the 15 Puzzle in 17 seconds. Not to be outdone by the troubled chess titan, my daughter recently witnessed me solve Soma in under a minute.

Bobby Fisher solving the 15 puzzle in 17 seconds on The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson

Bobby Fisher solving the 15 puzzle in 17 seconds on The Tonight Show with Johnny CarsonIf I didn’t already say it, Puzzle 15 is solved when the numbers are arranged in sequential order, a kind of numerology. That’s a clumsy transition to rip into what I really what to talk about: Ol’ Leather Apron himself and numbers.

Numerology is the belief that there is some synchromystical relationship with numbers. Pythagoras thought they carried secret codes, and this has carried over to influence everything from Nostradamus to tetraphobia, the fear of the number four. And, of course, there is a subset of numerology inclusive to interpreting the Whitechapel murders and Jack The Ripper. Here’s just one example from the zany world of numerology:

Mary Nichols is widely assumed to have been the first Ripper murder on Buck’s Row, on August 31, 1888. There’s a Pythagorean system of assigning letters to numbers that I’m not going to get into fully (you can look it up), but from August 31, one naturally comes to the initials JKS which then naturally leads to the name “James Kenneth Stephen,” I mean, any idiot can see that! Stephen is the guy who was a tutor for the House of Windsor. He’s part of that Ripper theory that supposes the whole thing was part of a conspiracy involving the British Royals. This is all from an online post on numerology in which the author triumphantly summarizes, “This is how the occult is used in solving murder mysteries. What ordinary men cannot see.” I must be super-ordinary; not only do I not see it, I thought the Whitechapel murders were unsolved.

Another tin hat post discusses the significance of the year 1888. If you add the numbers, you get 25. Ok, with you so far. Well, in numerology, 25 holds all sorts of sacred meanings. 25 represents “a dark time in Whitechapel” (no shit). For the assailant, it points to an “unbalanced” individual (see previous parenthetical). Also, “the person who was behind the Ripper killings was born with the characteristics of the eight influencing his life.” Ok, can I get a sniff of what that means? Well, he burned with ambition, enjoyed taking risks, was a loner, and on and on. You get the point. Obviously, we are giant steps away from behavioral profiling – that’s numerology.

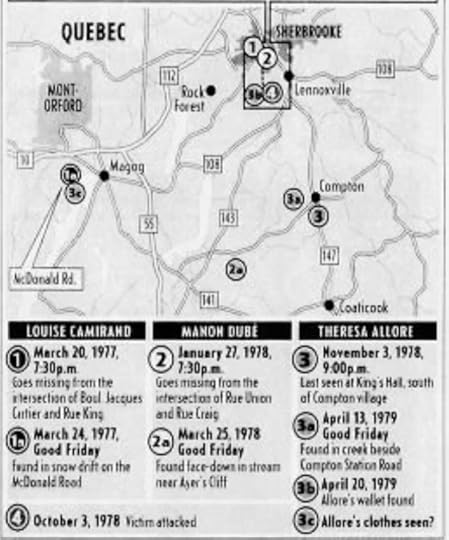

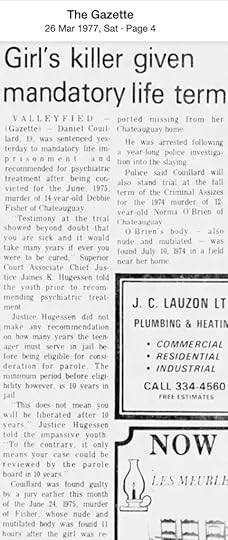

National Post error map – unlucky Good Friday

National Post error map – unlucky Good FridayIn 2002 The National Post mistakenly reported that all of the victims of the Eastern Townships murders were found on Good Friday, and I’ve never lived it down. Not only is that not true (Good Friday, 1977, was April 8), it wouldn’t mean anything even if it was. There’s a logical explanation for bodies turning up on holidays. People have time off. They can dedicate their leisure hours to strolling along lakes, streams, and woods. That’s what that means. It’s like saying a killer is motivated by the phases of the moon, which they did with Daniel Coulliard and the 74-75 murders of Norma O’Brien and Debbie Fisher. Ya? So?

Daniel Couillard guilty of the beating deaths of Debbie Fisher and Norma O’Brien – The Gazette, March 26, 1977

Daniel Couillard guilty of the beating deaths of Debbie Fisher and Norma O’Brien – The Gazette, March 26, 1977Show me a killer who committed all his murders on Good Friday, and I’d say you might have something.

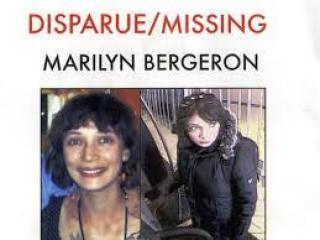

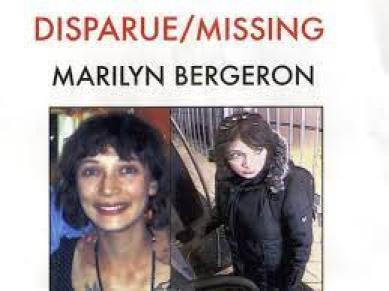

Marilyn Bergeron Marilyn Bergeron

Marilyn BergeronHere’s a puzzle. What happened to Marilyn Bergeron? This week marks the 15th anniversary of the disappearance of the 24-year-old girl who today would be thirty-nine. Bergeron left her family’s home in Quebec City for a walk on the morning of February 17, 2008. She did not return. An ATM security camera in Loretteville recorded her attempting to withdraw money early that afternoon; she was last seen almost five hours after leaving her home at a coffee shop in Levis. Several sightings of Marilyn have been reported since then, especially in areas of Ontario just outside Quebec, but none have been confirmed.

Quebec Police continue to speculate that Bergeron committed suicide, which is absurd. Fifteen years and no body; where did she go? The elephant’s graveyard? The family fears she met with foul play, possibly sold into the Quebec sex trade. Could someone fall off the map for 15 years and still be hiding in plain sight? Definitely.

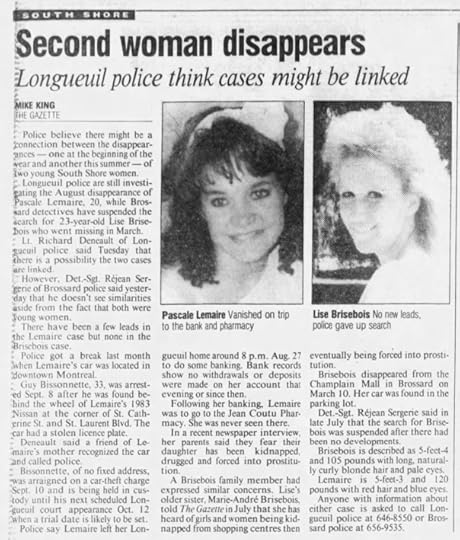

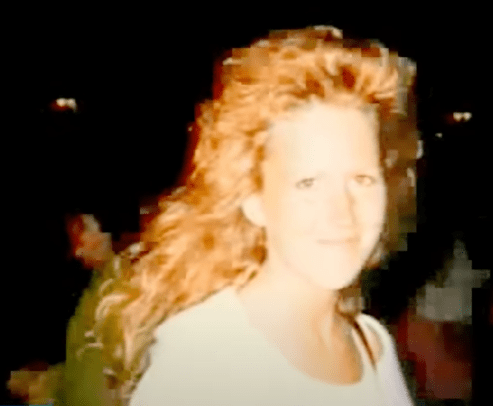

This was an immediate fear in the 1990 disappearance of Lise Brisebois. Before her remains were found in a field near Rainville, Brisebois had been missing for nine months, and speculation was that she had been abducted into the sex trade. In July 1990, her sister, Marie-Andree Brisebois, told the Montreal Gazette that she “heard of girls and women being kidnapped from shopping centres then eventually forced into prostitution.” By October, her parents reiterated this theory, telling the news media they feared “their daughter had been kidnapped, drugged and forced into prostitution.”

Pascale Lemaire and Lise Brisebois

Pascale Lemaire and Lise BriseboisThe idea gained momentum when, later that month, another young girl vanished on the way from her parent’s house to do some banking and visit a pharmacy. Twenty-year-old Pascale Lemaire was found later that October shot in a field at St. Mathieu de La Prairie. Guy Bissonnette would eventually face a second-degree murder charge for the death of Pascale Lemaire. In these cases, the narrative was not accurate, but the Quebec sex trade industry remains a threat to young women in the province. Like Bergeron, no one knows the whereabouts of Nathalie Godbout. The twenty-six-year-old has been missing for 22 years, last seen in September 2000 after leaving her home in Levis, Quebec, the same place from which Bergeron disappeared.

Finally, I promised you an update on the Brisebois case. One of the advantages of acting like the smartest guy in the room is that, if you’re lucky, someone will come along and tell you why they’re smarter. It turns out Guy Croteau isn’t the only suspect in the Brisebois murder. I was told that one of her boyfriends – and I have to couch it that way, but you know who I mean – apparently used to go hunting on the property in Rainville where she was found, and he had severe issues with “impulsivity” and “aggression.” Of course, I’ve heard this one before. Manon Dube was found on property owned by her family, so the family must have been involved. It’s cockeyed logic. If it is true, why isn’t Lise Brisebois’ boyfriend in jail? And what about Johanne Marsolais and Annette Labelle? The theory does not account for them. My money’s on the guy convicted of murder and a collection of sexual assaults, not a boyfriend, who might have been a bit disturbed.

Casse-Tête 15 – et la disparition de Marilyn Bergeron

Avez-vous entendu parler de Puzzle 15 ?

Je parie que vous l’avez fait, vous ne le savez tout simplement pas. Vous connaissez ces brouillages de tuiles 4 x 4 où vous devez réorganiser les pièces coulissantes en une image ? Popeye ? Les Pierrafeu ? C’est le puzzle 15, parfois appelé Gem, Boss ou Mystic Square.

Le casse-tête 15

Le casse-tête 15Le puzzle 15 était le fidget spinner original occupant des chiffres occupés un siècle avant l’iPhone. L’origine de Puzzle 15 est quelque chose d’un puzzle lui-même. C’est devenu un véritable engouement dans les années 1880. Le colporteur de jeux Sam Lloyd a dit qu’il l’avait inventé. Il ne l’a pas fait. En 2006, Jerry Slocum et Dic Sonneveld ont publié un livre entier – non pas sur les jeux en général, mais spécifiquement sur le 15 Puzzle – dans lequel ils ont décrypté certains de ses mystères :

“Sam Loyd n’a pas inventé le puzzle 15 et n’a rien à voir avec sa promotion ou sa vulgarisation. L’engouement pour les puzzles créé par le 15 Puzzle a commencé en janvier 1880 aux États-Unis et en avril en Europe. L’engouement a pris fin en juillet 1880 et le premier article de Sam Loyd sur le puzzle n’a été publié que seize ans plus tard, en janvier 1896. Loyd a affirmé pour la première fois en 1891 qu’il avait inventé le puzzle, et il a poursuivi jusqu’à sa mort une campagne de 20 ans pour prendre faussement crédit pour le casse-tête. Le véritable inventeur était Noyes Chapman, le maître de poste de Canastota, New York, et il a déposé une demande de brevet en mars 1880. »