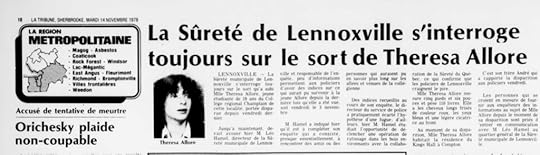

John Allore's Blog, page 5

April 30, 2022

The Aloha Motel Fire

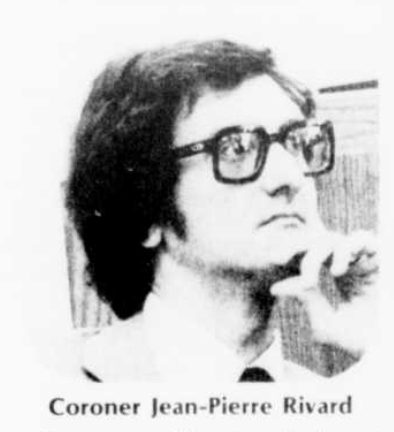

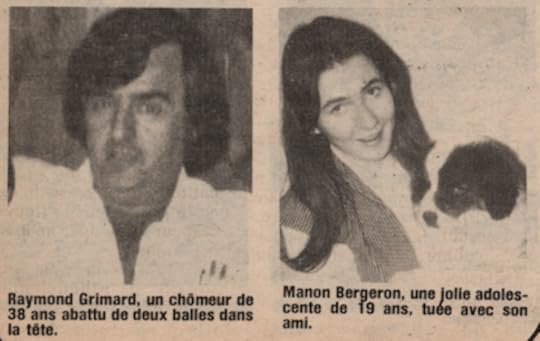

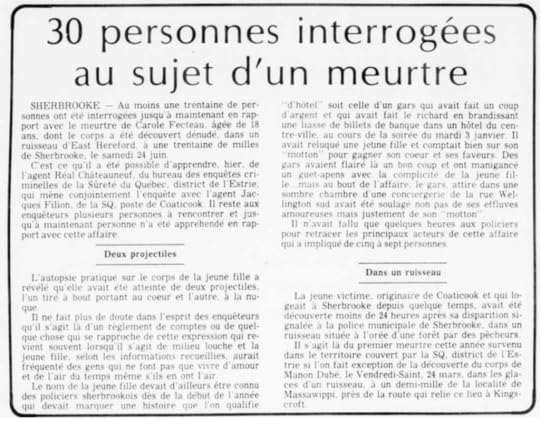

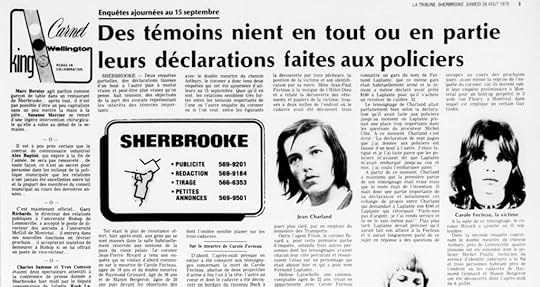

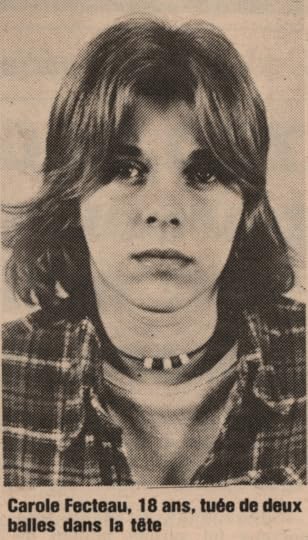

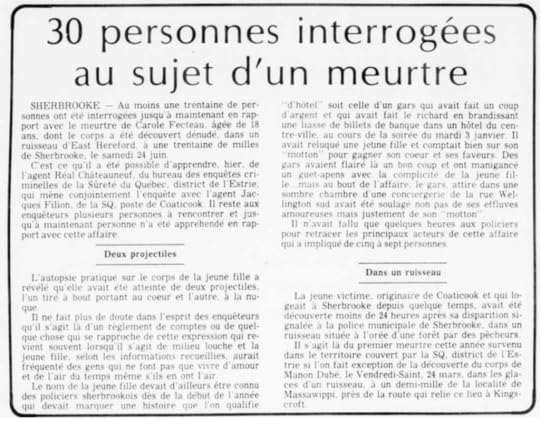

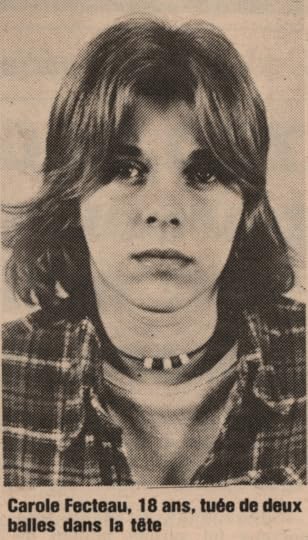

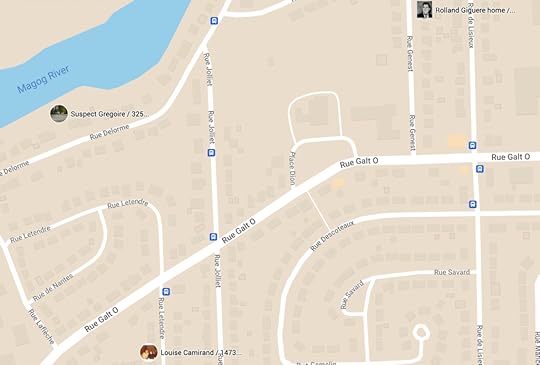

When Coroner Jean-Pierre Rivard adjourned his inquiry into the murders of Raymond Grimard, Manon Bergeron, and Carole Fecteau on October 16, police were still without a cooperative witness that would confirm their version of the darkness that transpired in late June and early July of 1978. Three weeks later they would have their compliant witness.

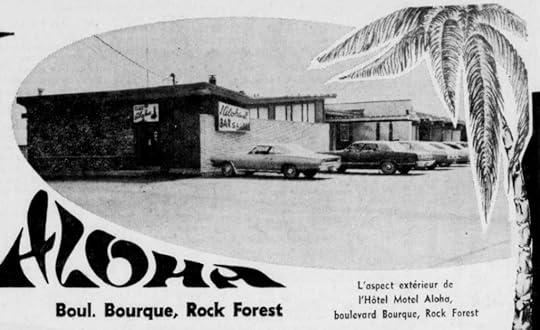

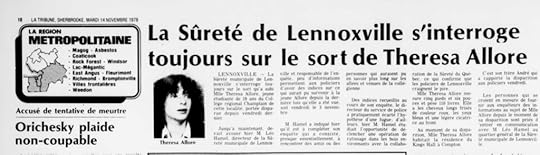

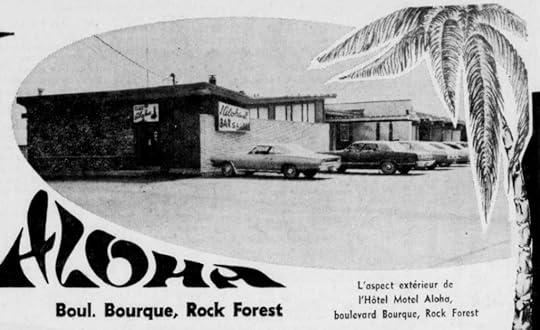

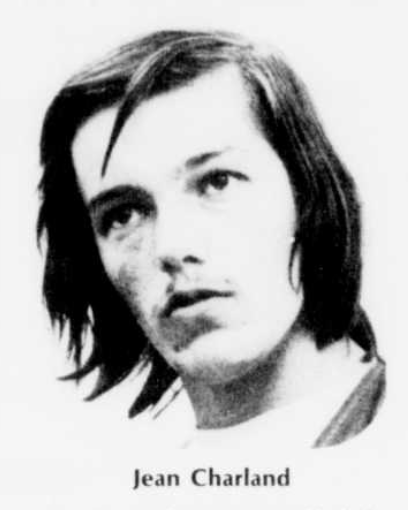

On November 10, 1978 someone attempted to set fire to the Aloha Motel in Rock Forest. You’ll recall Rock Forest as a bedroom community to the west of Sherbrooke (five years later it would become the setting of another motel drama: the massacre of two carpet layers by police at the Motel Chatillion). Tragedy was averted, the Sûreté du Quebec just happened to be across the street before the blaze was ignited. Police immediately arrested a nineteen-year-old suspect leaving the scene of the attempted arson: Jean Charland. Welcome to the world of Sherbrooke subterfuge (AKA S-Town), where even the police play a part in the underhanded shenanigans.

Charland pleaded not guilty and opted for a trial by judge and jury. Police tagged on charges of impaired driving and a hit and run. Agents from the Sûreté du Quebec reportedly saw Charland heading towards the motel located at 5790 Bourque Boulevard with two cans in his hands. In one of the rooms, police discovered a lighted candle and the two cans containing gasoline. Charland was apprehended, and the investigation was handed over to Réal Châteauneuf, the agent who just happened to be also assigned to the cases of Raymond Grimard and Manon Bergeron, and Carole Fecteau; the same agent who had followed the bank heisters to Hatley just prior to the Grimard-Bergeron murders.

What we know of these events would eventually come out in the trial of Fernand Laplante, set for January 1979, but subsequently postponed until that spring. I’m jumping ahead here because it’s important to know that these events played out over the weekend of November 10, 1978, during the time that Theresa Allore went missing, and her story was first reported in the local newspapers.

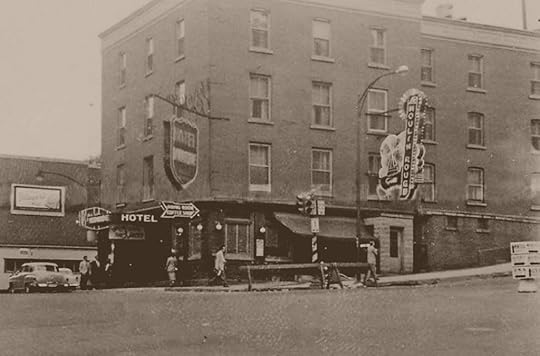

To begin with, Jean Charland was an arsonist of herostratic proportions well before the Aloha Motel incident. He was accustomed to receiving payments for contracts to burn down establishments where the owners (or the mob that controlled them) wished to liquidate the business and cut-and-run with the insurance proceeds. Charland was suspected of setting a fire at a Wellington Street South hotel. He may have played a part in the October blaze at the Ripplecove Inn in Ayer’s Cliff that killed 12 guests. So I have no problem believing Jean Charland accepted a contract to burn down the Aloha Motel. The question is, who put out the contract? Was it the owner, Paul Bergeron, as the police would have you believe, or was it someone who had a specific interest in setting-up Jean Charland so he would testify against Fernand Laplante? To put a blunt point on the question, did the Sûreté du Quebec, through an intermediary, put out a contract on the Aloha Motel? Because it sure looks like it.

In the aftermath of the Aloha Motel fire, Charland was effectively put under house arrest, confined to his parents’ home and ordered to obey a one o’clock curfew. Judge Yvon Roberge required that the 19-year-old meet every Thursday with agent Réal Châteauneuf. In other words, Chaland was to meet weekly with the Sûreté du Québec every week for 6 months until he finally got his story straight. If the Quebec legal process had shown this level of concern when Charland was merely a petty criminal there might never have been three murders committed in 1978 Sherbrooke. It’s important to note here that Jean Charland too was set to stand trial as a co-conspirator in the three 1978 summer murders, but where Laplante was clamped down, Charland was allowed to walk free and roam the streets of Sherbrooke doing as he willed; drug dealing, setting fires, and getting shot at (we’ll get to that).

At the trial in April 1979, even though he testified against Laplante, Charland equally admitted that he believed the police had set him up to perform the “arson contract on November 10 at the Motel Aloha, the purpose of which was to make [me] talk.” In fact, Charland only made a statement incriminating Fernand Laplante in the murder of Carole Fecteau on November 11, the day after the Aloha fire. Charland pointed out that he found it curious that the police arrested him at the scene, and he believed “in that moment and still thinks today that it was ‘a frame up’ to get [me] talking”.

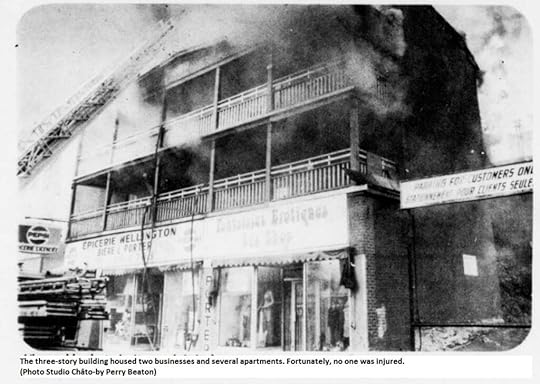

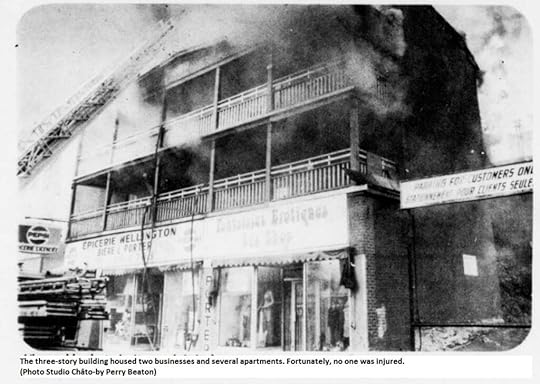

Fire in the hole Epicerie Wellington next to the Fantastic Erotica sex shop

Epicerie Wellington next to the Fantastic Erotica sex shopIf a business was paying out, through drug distribution or money laundering, there was no need to do anything. But if a business was dying or bled dry, better to take the one-time insurance cash and burn the place down. Sometimes it was just for revenge, or to take out a competitor. Arson could also get complicated, sometimes involving the darker side of municipal redevelopment and urban renewal.

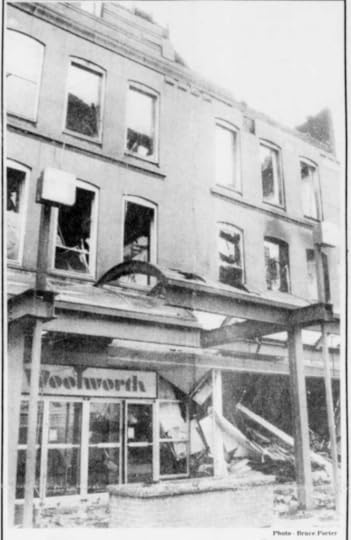

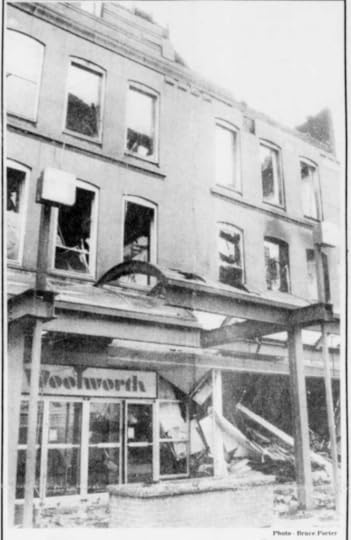

Woolworth fire, April 1, 1979

Woolworth fire, April 1, 1979In the late 1970s, arson was a tool of choice in the Townships underworld. In January 1977, The Lantern Inn in Georgeville, Quebec was destroyed by flames, but its popular nightclub, the discothèque La Poupée survived, only to be burned to the ground three years later. Later that fall someone set fire to Martin Furriers on Rue Frontenac in a blaze initially thought to be connected to the Charles Marion kidnapping. Nineteen-seventy-eight saw the Ripplecove Inn fire in Ayer’s Cliff. Arson was again suspected in a February 1979 blaze that raised the Royal Hotel at the corner of Belvedere and Minto (across from the Fusiliers armory). Then in April 1st, fire destroyed the Woolworth’s building at 79 Wellington North. In mid April, the Sherbrooke Fire Department reported that 1978 was the worst year for fires in the city’s history. Material losses rose from $900,000 in 1977 to $2.5 million in 1978. 437 fires were reported in the city with per capita losses costing each of Sherbrooke’s 86,000 residents $29.

By the end of the summer of 1979 police finally managed to catch a bone fide serial arsonist. Patrick Baron was charged with second degree murder for a fire that killed two women, including his 19-year-old girlfriend. Baron admitted to setting fires in Montreal and Sherbrooke while out on leave from the Pinel Psychiatric Institute.

Mario Vallières

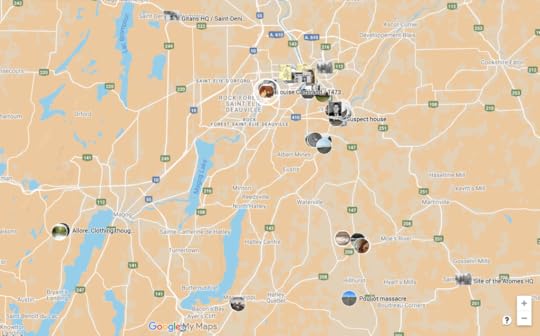

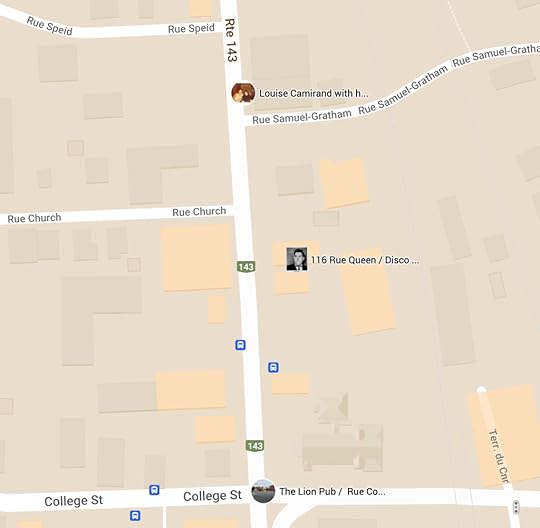

Mario VallièresIn addition to the Aloha fire, in April 1979, Jean Charland was suspected of setting a fire at a janitorial building at 83 Wellington Street South. Then later that June he did it again, igniting a blaze in the neighboring building at 79 Wellington Street South. For this job, Charland had a partner, Mario Vallières (ya, Charland and Grimard’s drug supplier). They received two grand to burn down a unit that housed nine apartments, a grocery store and a sex shop. At the time of these fires, Charland was preparing, then had just completed being the Crown’s star witness in the trial of Fernand Laplante, and was under special protection by the Sûreté du Québec. So apparently you could continue to break the law so long as the local police provided justice for crimes of their choosing (I’ve added the locations of these fires to our Google map).

Pay any price just to get youWhat came out at trial was something not revealed at the time of the Aloha Motel fire: Jean Charland had a partner in the arson plot. This was a man who at the time the Sûreté du Québec desperately wished to remain anonymous. Even today, I suspect parties in this whole affair would prefer that I not identify him. So I’m gonna identify him. His name is Regis Lachance, and this is what he told the court on May 2, 1979:

43-year-old Regis Lachance had a prior criminal record with convictions for gross indecency, fraud, theft, and breaking and entering. He said he had taken a contract to set the Aloha Motel fire from someone named Carrier who he had seen only two or three times ( this would be 25-year-old Normand Carrier who would eventually get 6 months for setting a fire in an apartment belonging to Mr. Orphir Phaneuf, Phaneuf committing the offense of not renting a unit to Carrier’s girlfriend). Lachance said he was to be paid a total of $5,000 after the job was completed, and received $2,500 in advance. Lachance accompanied Charland, who he had hired to do the job, first to a gas station to purchase gas and then to a Brasserie near the Woolco shopping centre, where they had a few beers before proceeding to the Aloha around 9:30 p.m. (for those keeping score, yes,this is the same Woolco where in 1983 police found the vehicle containing a shotgun and discarded clothing which eventually led to the whole cockup at the Motel Chatillon).

Aloha Motel 5790 Boul. Bourque, Rock Forest, QC

Aloha Motel 5790 Boul. Bourque, Rock Forest, QCCharland was driving a car belonging to Lachance’s sister. Lachance testified that he didn’t ride with him, “because I was afraid of him and he was pretty full of beer too”. I’m having a hard time understanding why a 43-year-old would be scared of a 19-year-old kid, but let’s continue. Lachance explained that he instead took a taxi to the motel. He entered the motel bar and proceeded down the passageway to unit 3 which he had rented earlier that day. He found Charland in the room and when everything was ready and a candle was lit and placed near some gas, he again left the way he had come in.

Charland went out the outside door (as we’ve seen with the Rock Forest Affair, this style of motel had a dual entrance) and was arrested immediately by officers Daniel Hébert and Réal Châteauneuf who cocked a 12-gauge shotgun in his face. Charland was bemused and visibly drunk. Lachance claimed he had seen a tow truck taking his sister’s car down the highway as he stood hitchhiking from the Aloha. He followed it to a garage where he was informed that the police had taken possession of it at the scene of a crime. You don’t have a tow truck at-the-ready unless the entire operation was pre-ordained. Lachance was never questioned by police for his part in the motel fire. Nor did the mysterious ‘Carrier’ ask for his $2,500 advance back, which Lachance claimed to have already spent. He denied knowing the whole thing was set up by police to get Charland, while admitting he was practically friends with the arson investigator, agent Plourde. In fact, Lachance seemed to be on good speaking terms with many members of the Sûreté du Québec.

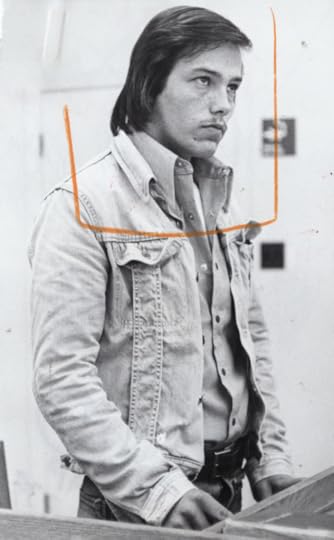

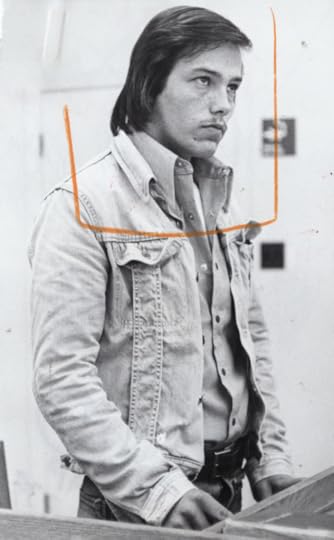

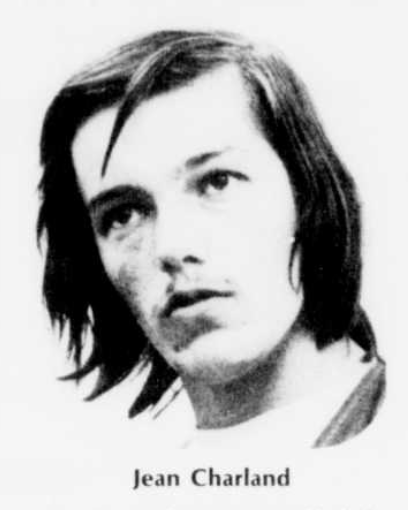

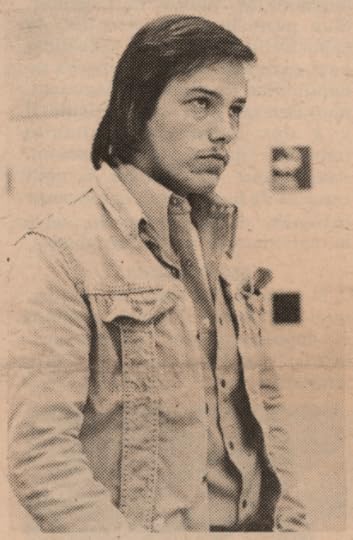

Jean Charland

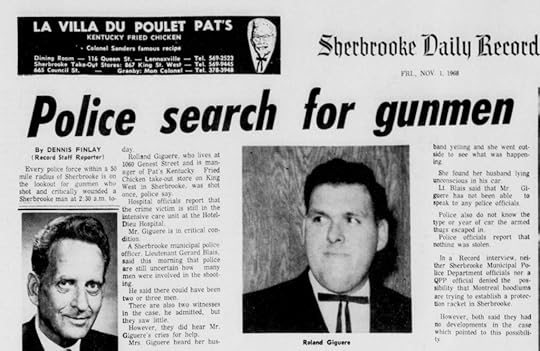

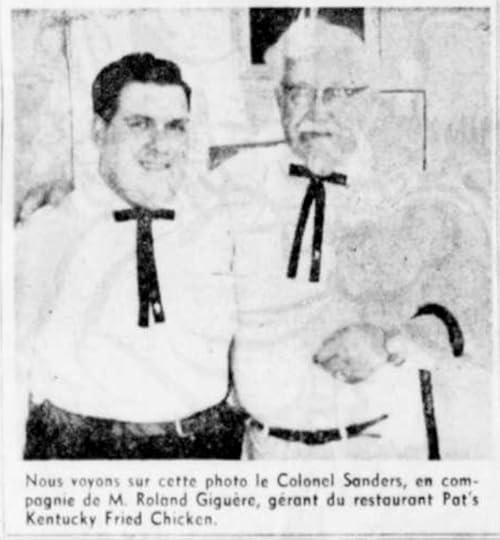

Jean CharlandAt the SQ headquarters, Charland gave a simple statement to officer Réal Châteauneuf about the Aloha case. Châteauneuf then turned matters, and asked Charland why he had retracted a statement given to the coroner on August 23 concerning the death of Carole Fecteau (wait, this is now about Fecteau? How’d that happen?). Charland refused to answer. It was close to midnight, and at this point the officers ordered lunch for Charland, consisting of fried chicken and three pints of beer ( the chicken, no doubt supplied by Pat’s KFC just down the street from the HQ). Recall that both Regis Lachance and the arresting officers said that Charland was already visibly drunk from the beers at the Woolco brasserie. After ‘lunch’, Châteauneuf then asked Charland if he knew anything about the murders of Raymond Grimard and Manon Bergeron, and then offered the young man police protection in exchange for his statement. Charland had already been shot at a number of times around King and Wellington in the months after the murders, someone in the underworld was apparently attempting to silence him. At this point the police used the word “bargain” to imply Charland would be protected in exchange for a cooperating statement. At approximately two in the morning, November 11, 1978, Jean Charland wrote his statement incriminating Fernand Laplante for the murders of Grimard, Bergeron and Fecteau.

Securing a false statement from a witness under hours of interrogation, while drunk and offering false bargains of protection maybe something covered under the Reid technique, but it’s never been proven as an effective technique to extract a confession under any scientific scrutiny. If the role of a police investigator is to, well, actually fucking investigate, then why not try that?

So what did Charland say happened? If you’re thinking that it’s odd that we’re at this point in our story – 5 months into the story, 4 chapters into this tale – and we still don’t know exactly what happened to our three victims, you’re right – It’s odd. It’s really fucking odd.

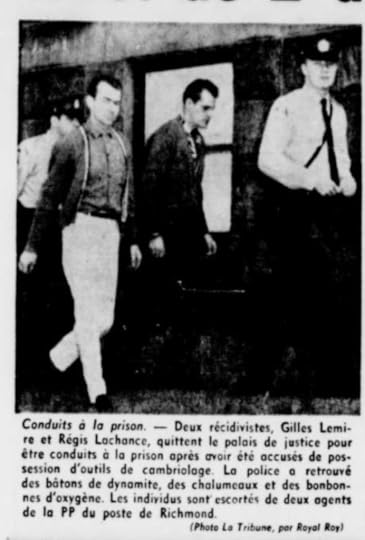

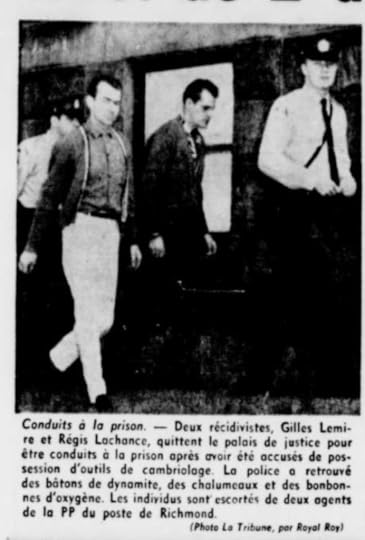

Regis Lachance (left) arrested for theft in 1962

Regis Lachance (left) arrested for theft in 1962And a gentle reminder here, while local police were “still wondering about the fate of Theresa Allore” on November 14, 1978, Jean Charland and Regis Lachance, two criminals with many prior convictions, were on the loose and left to their devices all through the month of November; during Theresa’s disappearance on November 3, right up to Charland’s arrest on November 10. And even after that, Charland was “ordered” to stay with his parents and Lachance remained free, he was never charged with anything in connection with the Aloha Motel fire, even though it was clearly Lachance who rented unit number 3. Recall that the guy police pegged as suspect number 1 in all of this, Fernand Laplante was at this time in prison serving a one year sentence for contempt of court, so he clearly had nothing to do with Theresa Allore’s disappearance or the motel fire. Why did a guy like Regis Lachance, a career criminal get to walk away scott-free from the scene of an arson? Unless he was working for the police.

I’ll add here that by now, I’m sure all of this sounds a little looney tunes, the product of an over-active imagination. Consider this: everything I’ve told you this far is backed up with evidence by then defense attorney Jean-Pierre Rancourt, the private investigator from that era named Robert Beullac, and today’s Sûreté du Québec cold case investigators. We’ll get there, I’m getting ahead of myself.

Flaming embersIn September 1979, the owner of the Aloha Motel. Paul Bergeron, filed a $300,000 civil claim against officers from the Estrie district of the Sûreté du Québec for arrest without warrant, illegal detention and mistreatment suffered on November 10, 1978 as well as for humiliation, loss of profits and the forced sale of his motel. Réal Châteauneuf was not named in the suit which included Sergeant Pierre Marcoux and agents Daniel Hébert, Robert Lauzon, Guy Lessard, all officers with hands in the Aloha case as well as the summer murders of Grimard, Bergeron and Fecteau.

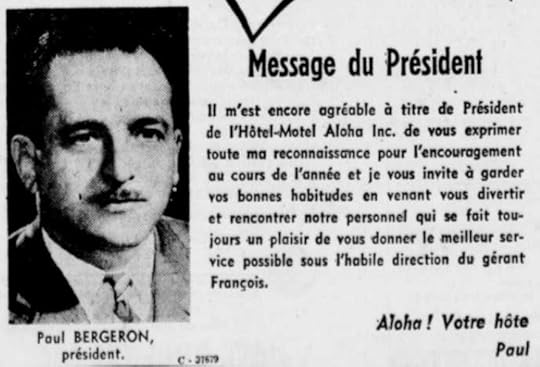

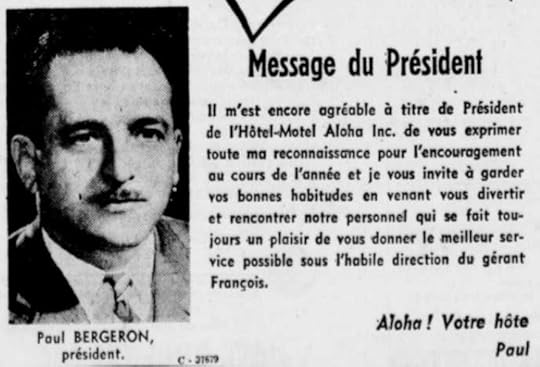

Paul Bergeron, owner of the Aloha Motel, Rock Forest, QC

Paul Bergeron, owner of the Aloha Motel, Rock Forest, QCIn the legal action Bergeron detailed how he had bought the Aloha Motel in 1967. How on the evening of November 10, 1978 he was arrested by Officer Hébert who took him to room no. 3 where the fire had started. There he was met by six or seven SQ officers who accused him of being complicit in the arson, one of them stating, “you have been dying for long enough, but you have gone too far”.

Bergeron was taken to headquarters on Don Bosco, detained and interrogated in a small office. He alleged that the police insisted on asking him “how much did you pay to burn down your motel?” According to Bergeron, Sergeant Marcoux, who was leading the interrogation, told him “Paul, you might as well admit it; we saw the gas and the candles in the room.” He mentioned to the officer that he had rented room No. 3 to an elderly person in his fifties (Regis Lachance), who claimed that the heating system in his residence was defective. According to Bergeron, Sergeant Marcoux insisted to him “say that you rented it to a young person” (Charland), which Bergeron refused to do. If the SQ was capable of such witness tampering, it is easy to now imagine them strong-arming Hélène Larochelle into saying her roommate, Carole Fecteau was scared of a “Claire and Fern”.

Guy Lessard (derrière)

Guy Lessard (derrière)It was at this point that officers began to beat Paul Bergeron. He received blows and slaps on each side of the head from his interrogator. Sergeant Marcoux repeated to him “you are going to speak” and continued to hit him in the head and in the face. The assault continued with officers pulling his hair and slamming his face into the cell wall. Bergeron pointed out that Constable Guy Lessard witnessed the scene and encouraged his colleague (Lessard would soon become one of the officers ‘investigating’ Theresa Allore’s murder). According to Bergeron, agent Lessard explained to him that “[they] weren’t trying to “frame” him but wanted to get details because he was a victim.” The hotelier added that he was locked in a cell, though charged with no crime, and the officers continued to beat him to the ground and trample him, all the while drinking beer and playing with their guns and cards. After a six-hour interrogation, Sergeant Marcoux told Bergeron, “We are good guys, but others will arrive later and they may not be as good”. Marcoux then said that his insurance would be canceled and that an uninsured motel was without value.

In January 1981 the Quebec Police Commission held a public inquiry into the conduct of Sergeant Pierre Marcoux, as well as Officers Guy Lessard and Robert Lauzon of the Sûreté du Québec. Agent Réal Chateauneuf then joined the fray and attempted to discredit Bergeron, now claiming that on the night of November 10, he “was drunk, staggered slightly and had a hesitant step”. At the conclusion of the inquiry in 1982, Sergeant Pierre Marcoux and constable Robert Lauzon were ordered to pay $7,500 in restitution to Paul Bergeron. Also implicated in the case was Quebec Justice Minister Marc Andre Bedard, who on behalf of the government was ordered to share the cost of the restitution, which was nowhere near Bergeron’s original lawsuit for $300,000. Bergeron was eventually forced to sell the Aloha Motel due to his financial difficulties. It is worth noting that by this time the incident at the Rock Forest Motel was only a year away. The owner of the Chatillon Motel in that affair would also go bankrupt due to police fuckery.

What was missing in the reporting on Paul Bergeron’s legal action against the Sûreté du Québec was any mention of the men who attempted to set fire to the Aloha Motel: Regis Lachance and Jean Charland. Without that information, the public could never connect that Bergeron’s suit was one more example of the police’s attempts to fabricate a narrative in the miscarriage of justice against Fernand Laplante. When you add up the evidence – the beating and harassment of Bergeron, the coercion of a confession from Charland by getting him drunk and the frame-up for the arson, the use of Lachance as a willing rube in the scheme – it all points to a police force desperate to convict a man at any cost. But the public never saw this. They were never provided the tools to decide for themselves.

Nineteen-eight-two was a long way from 1978. After winning their fourth consecutive Stanley Cup in 1978-79, in 1982 the Montreal Canadiens were eliminated in the first round by the upstart Quebec Nordiques. By 1982, René Lévesque and the Parti Québécois had largely abandoned their sovereigntist roots. ABBA, Blondie, The Doobie Brothers, The Jam, The Knack, The Sweet all called it quits in 1982. By this time, even I was a long way from Quebec, preparing to enter my first year of college in Ontario. When Paul Bergeron was finally awarded $7,500, all the facts had been trampled underfoot in a rush to judgment. All the important details were forgotten.

Now when I say this was a miscarriage of justice, ultimately, a miscarriage of justice against who? Next time: The trail of Fernand Laplante.

The post The Aloha Motel Fire first appeared on Who Killed Theresa?.

April 29, 2022

L’incendie au Aloha Motel

Lorsque le coroner Jean-Pierre Rivard a ajourné son enquête sur les meurtres de Raymond Grimard, Manon Bergeron et Carole Fecteau le 16 octobre, la police n’avait toujours pas de témoin coopératif qui confirmerait sa version de l’obscurité qui s’est déroulée fin juin et début juillet 1978 Trois semaines plus tard, ils auraient leur témoin complaisant.

Le 10 novembre 1978, quelqu’un a tenté de mettre le feu au motel Aloha à Rock Forest. Vous vous souviendrez de Rock Forest comme dortoir à l’ouest de Sherbrooke (cinq ans plus tard, il deviendrait le décor d’un autre drame de motel : le massacre de deux poseurs de tapis par la police au Motel Chatillion). La tragédie a été évitée, la Sûreté du Québec se trouvait juste de l’autre côté de la rue avant que l’incendie ne soit allumé. La police a immédiatement interpellé un suspect de dix-neuf ans quittant les lieux de la tentative d’incendie criminel : Jean Charland. Bienvenue dans le monde du subterfuge Sherbrookois, où même la police joue un rôle dans le drame sournois.

Charland a plaidé non coupable et a opté pour un procès devant juge et jury. La police a été accusée de conduite avec facultés affaiblies et de délit de fuite. Des agents de la Sûreté du Québec auraient vu Charland se diriger vers le motel situé au 5790, boulevard Bourque avec deux canettes à la main. Dans l’une des pièces, les policiers ont découvert une bougie allumée et les deux bidons contenant de l’essence. Charland est appréhendé et l’enquête est confiée à Réal Châteauneuf, l’agent qui vient d’être également affecté aux dossiers de Raymond Grimard et Manon Bergeron, et de Carole Fecteau; le même agent qui avait suivi les braquages de banque à Hatley juste avant les meurtres de Grimard-Bergeron.

Ce que l’on sait de ces événements sortira éventuellement du procès de Fernand Laplante, prévu pour janvier 1979, mais reporté par la suite à ce printemps. J’avance ici parce qu’il est important de savoir que ces événements se sont déroulés le week-end du 10 novembre 1978, à l’époque où Theresa Allore a disparu, et son histoire a été rapportée pour la première fois dans les journaux locaux.

Pour commencer, Jean Charland était un incendiaire aux proportions héroïques bien avant l’incident du motel Aloha. Il avait l’habitude de recevoir des paiements pour des contrats d’incendie d’établissements où les propriétaires (ou la foule qui les contrôlait) souhaitaient liquider l’entreprise et couper avec le produit de l’assurance. Charland était soupçonné d’avoir mis le feu à un hôtel de Wellington Street South, ainsi que de l’incendie d’octobre au Ripplecove Inn à Ayer’s Cliff qui a tué 12 invités. Je n’ai donc aucun problème à croire que Jean Charland a accepté un contrat pour incendier le motel Aloha. La question est, qui a signé le contrat ? Était-ce le propriétaire, Paul Bergeron, comme la police voudrait vous le faire croire, ou était-ce quelqu’un qui avait un intérêt particulier à piéger Jean Charland pour qu’il témoigne contre Fernand Laplante? Pour résumer la question, est-ce que la Sûreté du Québec, par l’intermédiaire d’un intermédiaire, a passé un contrat sur le motel Aloha? Parce que c’est sûr que ça y ressemble.

Au lendemain de l’incendie de l’Aloha Motel, Charland a été assigné à résidence, confiné au domicile de ses parents et condamné à respecter un couvre-feu à une heure. Le juge Yvon Roberge a exigé que le jeune de 19 ans rencontre tous les jeudis l’agent Réal Châteauneuf. En d’autres termes, Chaland devait rencontrer la Sûreté du Québec toutes les semaines pendant 6 mois jusqu’à ce qu’il finisse par mettre son histoire au clair. Si le processus judiciaire québécois avait montré ce niveau d’inquiétude alors que Charland n’était qu’un petit criminel, il n’y aurait peut-être jamais eu trois meurtres commis en 1978 à Sherbrooke. Il est important de noter ici que Jean Charland a également été jugé en tant que co-conspirateur dans les trois meurtres de l’été 1978, mais là où Laplante a été réprimé, Charland a été autorisé à marcher librement et à errer dans les rues de Sherbrooke en faisant ce qu’il voulait. trafic de drogue, incendies et tirs dessus (nous y reviendrons).

Au procès en avril 1979, bien qu’il ait témoigné contre Laplante, Charland a également admis qu’il croyait que la police l’avait piégé pour exécuter « le contrat d’incendie criminel du 10 novembre au Motel Aloha, dont le but était de [me] parler.” En effet, Charland n’a fait une déclaration incriminant Fernand Laplante dans le meurtre de Carole Fecteau que le 11 novembre, au lendemain de l’incendie d’Aloha. Charland a souligné qu’il trouvait curieux que la police l’ait arrêté sur les lieux, et il a cru “à ce moment et pense encore aujourd’hui que c’était” un coup monté “pour [me] parler”.

Fire in the hole Epicerie Wellington à côté du sex-shop Fantastic Erotica

Epicerie Wellington à côté du sex-shop Fantastic EroticaSi une entreprise payait, par le biais de la distribution de drogue ou du blanchiment d’argent, il n’y avait rien à faire. Mais si une entreprise était en train de mourir ou saignée à sec, mieux vaut prendre l’argent de l’assurance unique et brûler l’endroit. Parfois, c’était juste pour se venger ou pour éliminer un concurrent. Les incendies criminels pourraient également se compliquer, impliquant parfois l’obscurité côté du redéveloppement municipal et de la rénovation urbaine.

Incendie Woolworth , April 1, 1979

Incendie Woolworth , April 1, 1979À la fin des années 1970, les incendies criminels étaient un outil de choix dans la pègre des Cantons. En janvier 1977, The Lantern Inn à Georgeville, au Québec, a été détruit par les flammes, mais sa boîte de nuit populaire, la discothèque La Poupée a survécu, pour être incendiée trois ans plus tard. Plus tard cet automne, quelqu’un a mis le feu à Martin Furriers sur la rue Frontenac dans un incendie initialement supposé être lié à l’enlèvement de Charles Marion. En 1978, l’incendie du Ripplecove Inn à Ayer’s Cliff a eu lieu. Un incendie criminel a de nouveau été soupçonné lors d’un incendie en février 1979 qui a soulevé l’hôtel Royal au coin du Belvédère et de Minto (en face de l’armurerie des Fusiliers). Puis, le 1er avril, un incendie a détruit le bâtiment de Woolworth au 79 Wellington North. À la mi-avril, le service d’incendie de Sherbrooke rapporte que 1978 a été la pire année pour les incendies dans l’histoire de la ville. Les pertes matérielles sont passées de 900 000 $ en 1977 à 2,5 millions $ en 1978. 437 incendies ont été signalés dans la ville avec des pertes par habitant coûtant 29 $ à chacun des 86 000 résidents de Sherbrooke.

À la fin de l’été 1979, la police a finalement réussi à attraper un incendiaire en série de bonne foi, Patrick Baron, accusé de meurtre au deuxième degré pour un incendie qui a tué deux femmes, dont sa petite amie de 19 ans. Baron a admis avoir mis le feu à Montréal et à Sherbrooke alors qu’il était en congé de l’Institut psychiatrique Pinel.

Mario Vallières

Mario VallièresEn plus de l’incendie d’Aloha, en avril 1979, Jean Charland est soupçonné d’avoir mis le feu à un immeuble de conciergerie au 83, rue Wellington Sud. Plus tard en juin, il récidiva, déclenchant un incendie dans l’immeuble voisin au 79, rue Wellington Sud. Pour ce travail, Charland avait un associé, Mario Vallières (ya, le fournisseur de médicaments de Charland et Grimard). Ils ont reçu deux mille dollars pour incendier une unité qui abritait neuf appartements, une épicerie et un sex-shop. Au moment de ces incendies, Charland se prépare, puis vient d’achever d’être le témoin vedette de la Couronne au procès de Fernand Laplante, et est sous la protection spéciale de la Sûreté du Québec. Donc, apparemment, vous pourriez continuer à enfreindre la loi tant que la police locale rendrait justice pour les crimes de son choix.

Pay any price just to get youCe qui est sorti au procès et qui n’avait pas été révélé au moment de l’incendie du motel Aloha : Jean Charland avait un partenaire dans le complot d’incendie criminel. Il s’agit d’un homme qui, à l’époque, la Sûreté du Québec souhaitait désespérément rester anonyme. Même aujourd’hui, je soupçonne que les parties dans toute cette affaire préféreraient que je ne l’identifie pas. Il s’appelle Régis Lachance, et voici ce qu’il a déclaré au tribunal le 2 mai 1979 :

Régis Lachance, 43 ans, avait un casier judiciaire avec des condamnations pour indécence grossière, fraude, vol et introduction par effraction. Il a dit qu’il avait pris un contrat pour mettre le feu à l’Aloha Motel d’un nommé Carrier qu’il n’avait vu que deux ou trois fois (il s’agirait de Normand Carrier, 25 ans, qui finirait par écoper de 6 mois pour avoir mis le feu dans un appartement appartenant à M. Orphir Phaneuf, Phaneuf ayant commis l’infraction de ne pas louer une unité à la petite amie de Carrier). Lachance a déclaré qu’il devait être payé un total de 5 000 $ une fois le travail terminé et qu’il avait reçu 2 500 $ à l’avance. Lachance a accompagné Charland, qu’il avait embauché pour faire le travail, d’abord à une station-service pour acheter de l’essence, puis à une Brasserie près du centre commercial Woolco, où ils ont bu quelques bières avant de se rendre à l’Aloha vers 21h30. (pour ceux qui tiennent les comptes, oui, c’est le même Woolco où, en 1983, la police a trouvé le véhicule contenant un fusil de chasse et des vêtements jetés, ce qui a finalement conduit à tout le cockup au Motel Chatillon).

Aloha Motel 5790 Boul. Bourque, Rock Forest, QC

Aloha Motel 5790 Boul. Bourque, Rock Forest, QCCharland conduisait une voiture appartenant à la sœur de Lachance. Lachance a témoigné qu’il n’a pas roulé avec lui, “parce que j’avais peur de lui et qu’il était pas mal bourré de bière aussi”. J’ai du mal à comprendre pourquoi un homme de 43 ans aurait peur d’un gamin de 19 ans, mais continuons. Lachance a expliqué qu’il avait plutôt pris un taxi pour se rendre au motel. Il est entré dans le bar du motel et a emprunté le passage menant à l’unité 3 qu’il avait louée plus tôt dans la journée. Il trouva Charland dans la chambre et quand tout fut prêt et qu’une bougie fut allumée et placée près du gaz, il repartit par le chemin par lequel il était entré.

Jean Charland

Jean CharlandCharland est sorti par la porte extérieure (comme nous l’avons vu avec l’affaire Rock Forest, ce style de motel a une double entrée) et a été arrêté immédiatement par les agents Daniel Hébert et Réal Châteauneuf qui ont armé un fusil de chasse de calibre 12 dans son visage. Charland était perplexe et visiblement ivre. Lachance a affirmé avoir vu une dépanneuse emmener la voiture de sa sœur sur l’autoroute alors qu’il faisait de l’auto-stop depuis l’Aloha. Il l’a suivi jusqu’à un garage où il a été informé que la police en avait pris possession sur les lieux d’un crime. Vous n’avez pas de dépanneuse prête à l’emploi à moins que toute l’opération n’ait été pré-ordonnée. Lachance n’a jamais été interrogé par police pour son rôle dans l’incendie du motel. Le mystérieux “Carrier” n’a pas non plus demandé son avance de 2 500 $, que Lachance prétendait avoir déjà dépensée. Il a nié savoir que tout avait été monté par la police pour attraper Charland, tout en admettant qu’il était pratiquement ami avec l’enquêteur sur les incendies criminels, l’agent Plourde. En fait, Lachance semblait être en bons termes avec plusieurs membres de la Sûreté du Québec.

Au quartier général de la SQ, Charland fait une simple déclaration à l’agent Réal Châteauneuf au sujet de l’affaire Aloha. Châteauneuf tourna alors les choses et demanda à Charland pourquoi il était revenu sur une déclaration faite au coroner le 23 août concernant la mort de Carole Fecteau (attendez, il s’agit maintenant de Fecteau ? Comment cela s’est-il passé ?). Charland a refusé de répondre. Il était près de minuit, et à ce moment-là, les officiers ont commandé un déjeuner pour Charland, composé de poulet frit et de trois pintes de bière (le poulet, sans aucun doute fourni par Pat’s KFC juste en bas de la rue du QG). Rappelons que Régis Lachance et les agents qui l’ont arrêté ont déclaré que Charland était déjà visiblement ivre des bières de la brasserie Woolco. Après le « déjeuner », Châteauneuf demande alors à Charland s’il est au courant des meurtres de Raymond Grimard et de Manon Bergeron, puis offre au jeune homme une protection policière en échange de sa déclaration. Charland avait déjà été abattu à plusieurs reprises autour de King et de Wellington dans les mois qui ont suivi les meurtres, quelqu’un dans le monde souterrain tentait apparemment de le faire taire. À ce stade, la police a utilisé le mot « négocier » pour impliquer que Charland serait protégé en échange d’une déclaration de coopération. Vers deux heures du matin, le 11 novembre 1978, Jean Charland rédige sa déclaration incriminant Fernand Laplante pour les meurtres de Grimard, Bergeron et Fecteau.

Obtenir une fausse déclaration d’un témoin pendant des heures d’interrogatoire, en état d’ébriété et en offrant de fausses offres de protection peut-être quelque chose couvert par la technique Reid, mais cela n’a jamais été prouvé comme une technique efficace pour extraire une confession sous un examen scientifique. Si le rôle d’un enquêteur de la police est, eh bien, d’enquêter, alors pourquoi ne pas essayer ?

Alors qu’est-ce que Charland a dit qu’il s’était passé ? Si vous pensez qu’il est étrange que nous soyons à ce stade de notre histoire – 5 mois dans l’histoire, 4 chapitres dans ce conte – et que nous ne savons toujours pas exactement ce qui est arrivé à nos trois victimes, vous avez raison – C’est étrange. C’est vraiment bizarre.

Régis Lachance (à gauche) arrêté pour vol en 1962

Régis Lachance (à gauche) arrêté pour vol en 1962Et un doux rappel ici, alors que la police locale “s’interrogeait encore sur le sort de Thérèse Allore” le 14 novembre 1978, Jean Charland et Régis Lachance, deux criminels aux nombreuses condamnations antérieures, étaient en cavale et livrés à eux-mêmes tout du long le mois de novembre ; lors de la disparition de Theresa le 3 novembre, jusqu’à l’arrestation de Charland le 10 novembre. Et même après cela, Charland a été «ordonné» de rester avec ses parents et Lachance est resté libre, il n’a jamais été accusé de quoi que ce soit en rapport avec l’incendie du motel Aloha, même si c’était clairement Lachance qui louait l’unité numéro 3. Rappelons que le gars de la police identifié comme suspect numéro 1 dans tout ça, Fernand Laplante était à ce moment en prison purgeant une peine d’un an pour outrage au tribunal, donc il n’avait clairement rien à voir avec la disparition de Theresa Allore ou l’incendie du motel. Pourquoi un gars comme Régis Lachance, un criminel de carrière, est-il parvenu à s’en sortir sans scott de la scène d’un incendie criminel ? Sauf s’il travaillait pour la police.

Flaming embersEn septembre 1979, le propriétaire de l’Aloha Motel. Paul Bergeron, a déposé une poursuite civile de 300 000 $ contre des agents du district de l’Estrie de la Sûreté du Québec pour arrestation sans mandat, détention illégale et mauvais traitements subis le 10 novembre 1978 ainsi que pour humiliation, manque à gagner et vente forcée de son motel . Réal Châteauneuf n’a pas été nommé dans la poursuite qui incluait le sergent Pierre Marcoux et les agents Daniel Hébert, Robert Lauzon, Guy Lessard, tous des officiers ayant des mains dans l’affaire Aloha ainsi que les meurtres estivaux de Grimard, Bergeron et Fecteau.

Paul Bergeron, propriétaire du motel Aloha, Rock Forest, QC

Paul Bergeron, propriétaire du motel Aloha, Rock Forest, QCDans l’action en justice, Bergeron a détaillé comment il avait acheté le motel Aloha en 1967. Comment le soir du 10 novembre 1978, il a été arrêté par l’agent Hébert qui l’a emmené dans la chambre no. 3 où le feu avait commencé. Là, il a été accueilli par six ou sept agents de la SQ qui l’ont accusé d’être complice de l’incendie criminel, l’un d’eux déclarant : « tu es mort depuis assez longtemps, mais tu es allé trop loin ».

Bergeron a été emmené au quartier général sur Don Bosco, détenu pendant 20 minutes et interrogé dans un petit bureau. Il a allégué que la police avait insisté pour lui demander « combien avez-vous payé pour incendier votre motel ? » Selon Bergeron, le sergent Marcoux, qui menait l’interrogatoire, lui aurait dit : « Paul, autant l’admettre ; nous avons vu le gaz et les bougies dans la chambre.” Il a mentionné à l’agent qu’il avait loué chambre no 3 à une personne âgée dans la cinquantaine (Régis Lachance) qui prétendait que le système de chauffage de sa résidence était défectueux. Selon Bergeron, le sergent Marcoux a insisté pour lui « dire que vous l’avez loué à un jeune » (Charland), ce que Bergeron a refusé de faire. Si la SQ était capable de telles subornations de témoins, il est facile de les imaginer maintenant en train de forcer Hélène Larochelle à dire que sa colocataire, Carole Fecteau avait peur d’une « Claire et Fern ».

C’est à ce moment que les agents ont commencé à battre Paul Bergeron. Il a reçu des coups et des gifles de chaque côté de la tête de son interrogateur. Le sergent Marcoux lui répète « tu vas parler » et continue de le frapper à la tête et au visage. L’agression s’est poursuivie, les agents lui tirant les cheveux et lui cognant le visage contre le mur de la cellule. Bergeron a souligné que le gendarme Guy Lessard avait été témoin de la scène et avait encouragé son collègue (Lessard deviendrait bientôt l’un des agents « enquêtant » sur le meurtre de Theresa Allore). Selon Bergeron, l’agent Lessard a expliqué à M. Bergeron qu'”[ils] n’essayaient pas de le “piéger” mais voulaient obtenir des détails parce qu’il était une victime”. L’hôtelier a ajouté qu’il était enfermé dans une cellule, bien qu’inculpé d’aucun crime, et que les agents aient continué à le frapper à terre et à le piétiner, tout en buvant de la bière et en jouant avec leurs fusils et leurs cartes. Après un interrogatoire de six heures, le sergent Marcoux a dit à Bergeron : « Nous sommes de bons gars, mais d’autres arriveront plus tard et ils ne seront peut-être pas aussi bons ». Marcoux a alors dit que son assurance serait annulée et qu’un motel non assuré n’avait aucune valeur.

Guy Lessard (derrière)

Guy Lessard (derrière)En janvier 1981, la Commission de police du Québec a tenu une enquête publique sur la conduite du sergent Pierre Marcoux, ainsi que des agents Guy Lessard et Robert Lauzon de la Sûreté du Québec. L’agent Réal Chateauneuf s’est alors joint à la mêlée et a tenté de discréditer Bergeron, affirmant maintenant que dans la nuit du 10 novembre, il « était ivre, titubait légèrement et avait un pas hésitant ». À la fin de l’enquête en 1982, le sergent Pierre Marcoux et le constable Robert Lauzon ont été condamnés à verser 7 500 $ en dédommagement à Paul Bergeron. Le ministre de la Justice du Québec, Marc-André Bédard, était également impliqué dans l’affaire. Au nom du gouvernement, il a été ordonné de partager le coût de la restitution, qui était loin d’être proche de la poursuite initiale de Bergeron qui était de 300 000 $. Bergeron a finalement été contraint de vendre le motel Aloha en raison de ses difficultés financières. Il convient de noter qu’à ce moment-là, l’incident au Rock Forest Motel n’était qu’un an. Le propriétaire du motel Châtillon dans cette affaire ferait également faillite en raison de conneries policières.

Ce qui manque dans le reportage sur la poursuite de Paul Bergeron contre la Sûreté du Québec, c’est la mention des hommes qui ont tenté de mettre le feu au motel Aloha : Régis Lachance et Jean Charland. Sans cette information, le public ne pourrait jamais comprendre que la poursuite de Bergeron était un exemple de plus des tentatives de la police de fabriquer un récit dans l’erreur judiciaire contre Fernand Laplante. Lorsque vous additionnez les preuves – les coups et le harcèlement de Bergeron, la coercition d’une confession de Charland en le saoulant et la mise en scène de l’incendie criminel, l’utilisation de Lachance comme agent volontaire dans le stratagème – tout indique une force de police désespérée de condamner un homme à tout prix. Mais le public n’a jamais vu cela. Ils n’ont jamais eu les outils pour décider par eux-mêmes.

1982 était loin de 1978. Après avoir remporté leur quatrième Coupe Stanley consécutive en 1978-79, en 1982, les Canadiens de Montréal ont été éliminés au premier tour par les Nordiques de Québec. En 1982, René Lévesque et le Parti québécois avaient en grande partie abandonné leurs racines souverainistes. ABBA, Blondie, The Doobie Brothers, The Jam, The Knack, The Sweet ont tous arrêté en 1982. À cette époque, même moi, j’étais loin du Québec et je me préparais à entrer en première année de collège en Ontario. Lorsque Paul Bergeron a finalement obtenu 7 500 $, tous les faits avaient été foulés aux pieds dans une précipitation au jugement.

Prochaine fois : Le sentier de Fernand Laplante.

The post L’incendie au Aloha Motel first appeared on Who Killed Theresa?.

April 24, 2022

Les trois meurtres: avenues sans fin

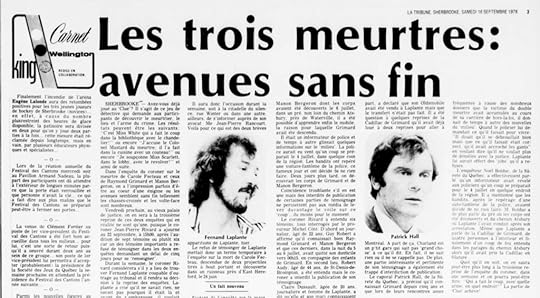

“Avez-vous déjà joué au Clue ? Il s’agit de ce jeu de détective qui demande aux participants de découvrir le meurtrier, le lieu et l’arme du crime. Les résultats peuvent être les suivants: “C’est Miss White qui a fait le coup dans la bibliothèque avec le chandelier'” ou encore “J’accuse le Colonel Mustard du meurtre; il l a fait dans la cuisine avec un couteau! ” ou encore “Je soupçonne Miss Scarlett, dans le lobby, avec le revolver! ” et ainsi de suite.

Dans l’enquête du coroner sur le meurtre de Carole Fecteau et ceux de Raymond Grimard et Manon Bergeron on a l ‘impression parfois d’être au coeur d’une énigme ou les avenues semblent sans fin tellement les chassés-croisés et les volte-face sont nombreux.”

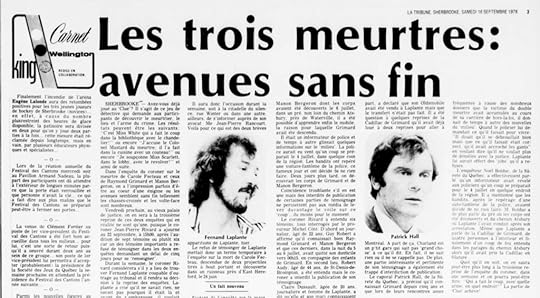

“Les trois meurtres: avenues sans fin”, La Tribune, 16 Septembre, 1978

“Les trois meurtres: avenues sans fin”, La Tribune, 16 Septembre, 1978

“Les trois meurtres: avenues sans fin”, La Tribune, 16 Septembre, 1978Revenez en arrière et rappelez-vous l’ouverture de la série de Patricia Pearson dans le National Post, Who Killed Theresa? Sa première phrase était : “Nous avons tendance à considérer les mystères non résolus comme un parlour game”. 24 ans plus tôt, Sherbrooke 1978, les rédacteurs de La Tribune assimilaient les meurtres de Grimard, Bergeron et Fecteau à une partie de Clue. Pourquoi se soucier de ces petits voyous et de ces trafiquants de drogue ? Parce qu’ils peuvent détenir la clé pour résoudre votre plus grand mystère personnel – celui que vous ne pouvez pas résoudre est celui qui empêche votre cœur de se réparer. Celle qui vous propulse et vous immobilise dans un lieu et dans le temps.

Calisse de merde

Calisse de merdeDans son infinie sagesse, le coroner Jean-Pierre Rivard a décidé que son enquête serait en trois volets : les enquêtes sur les meurtres de Raymond Grimard, Manon Bergeron et Carole Fecteau seraient toutes faites ensemble. On ne sait pas si cela a été fait par économie et par opportunité, ou sous la pression de la police, mais le résultat de la création d’un nœud gordien de confusion, il était difficile de séparer les « rebondissements » de tous les témoignages et de déterminer quelles informations appartenaient à quelle procédure pénale potentielle. Comment argumenter trois à la fois, si tout le but du processus du coroner est de déterminer si oui ou non un acte criminel a été réellement commis, et par qui? Et si la conclusion était trois assassins différents ? Le coroner Rivard avait une réponse à cela aussi. Son processus avait déjà prédéterminé l’identité du coupable : Fernand Laplante.

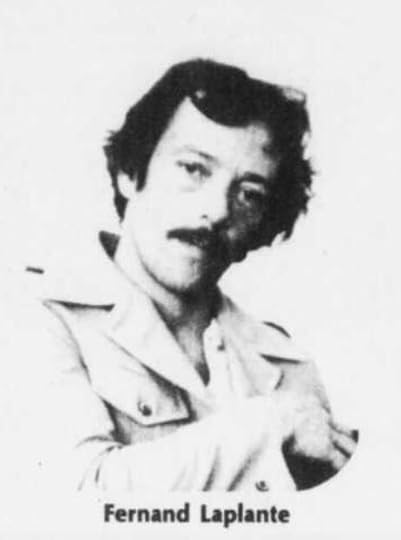

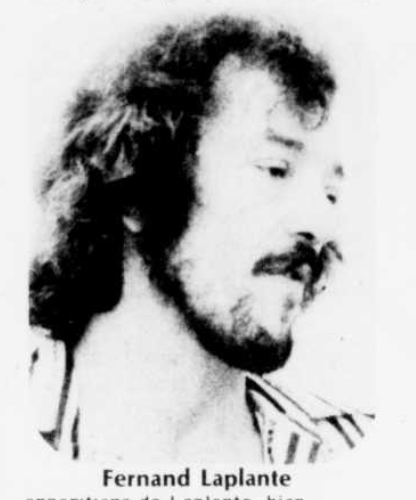

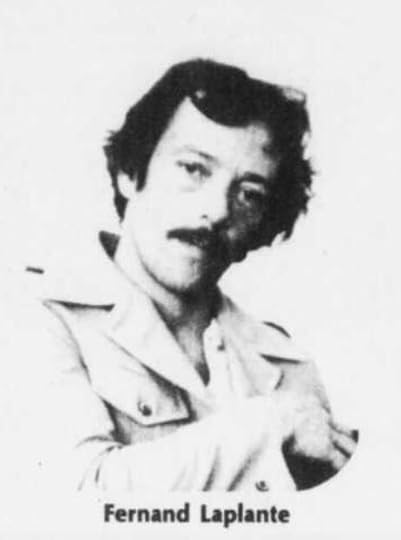

Fernand Laplante

Fernand LaplanteVous devriez maintenant vous demander qui était ce Fernand Laplante? Il n’était pas le fils de mère nature. Laplante n’était certainement pas étranger à la pègre sherbrookoise. En 1965, à l’âge de 20 ans, il purge une peine de six mois au pénitencier Saint-Vincent-de-Paul pour le cambriolage d’un garage de Coaticook. En 1969, il écope de deux autres années pour introduction par effraction. Apparemment, la charge n’a jamais bloqué. En 1970, Laplante et son associé Gaston Brochu sont pris en flagrant délit avec 27 000 $ de vêtements pour hommes d’une mercerie de Magog cachés dans les camions de leurs voitures. En 1971, il tente de cambrioler la maison d’un collectionneur d’armes légères, toujours à Magog. En 1974, Laplante avait accumulé quinze condamnations lorsqu’il fut de nouveau arrêté pour avoir tenté de voler un coffre-fort du marché Félix à Sherbrooke. Vol qualifié, cambriolage, introduction par effraction ; mais pas de meurtre.

Après la tentative de braquage de banque de juillet 1978 à Hatley (auquel Laplante était partie avec Jean Charland) et les meurtres de Grimard et Bergeron qui suivirent rapidement deux jours plus tard, la police arrêta Laplante le 3 août à Montréal lors d’une tentative de hold-up. Quelqu’un qui a travaillé de près sur les cas de Grimard et Bergeron m’a dit que la police soupçonnait Laplante d’avoir commis des meurtres dans son passé, mais pas ces meurtres : « Peu importait qu’il n’ait pas tué Grimard et Bergeron – ils le voulaient tellement. ”

Jean-Pierre Rivard débute son enquête du coroner à la fin août 1978. Le témoin vedette est Jean Charland. Au début, le témoignage de Charland s’est bien passé. Il a raconté au tribunal comment il était au chômage, comment Carole Fecteau était la copine de son petit frère et qu’il avait vu Fecteau deux ou trois fois « tout au plus », et comment lui et son frère et « deux autres mecs » avaient volé le véhicule d’Hélène Larochelle. (colocataire de Fecteau).

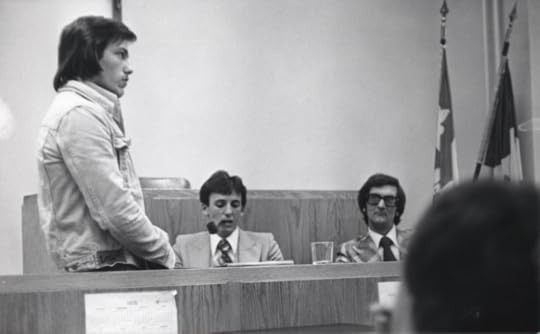

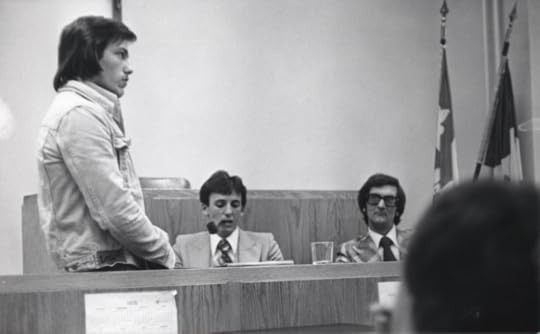

Charland à gauche, Rivard à droite (peut-être Michel Côté centre)

Charland à gauche, Rivard à droite (peut-être Michel Côté centre)Lorsque l’interrogatoire s’adressa à Fernand Laplante, les choses devinrent étranges. Charland a déclaré qu’il connaissait le gars, qu’il était habituellement armé et qu’il avait prêté 160 $ à Laplante pour qu’il puisse acheter un revolver de calibre .32. Alors que le procureur Michel Côte continuait de presser Jean Charland au sujet de Fernand Laplante, Charland s’est soudain écrié : « La déclaration de sept pages que j’ai faite à la police est fausse d’un bout à l’autre. J’étais fatigué et j’ai réussi parce que la police m’avait dit que Laplante m’avait recueilli jusqu’au cou et que je voulais le recueillir aussi!”

Pour les non-initiés, ce que Charland voulait dire, c’est que la police a dit à Charland que Leplante l’avait blâmé pour les meurtres, alors Charland s’est retourné contre Laplante et a dit que c’était en fait lui qui avait tué les trois victimes. Mentir à un témoin lors d’un interrogatoire de police est généralement mal vu car il n’y a aucune preuve scientifique que la technique produise des résultats, mais ce n’est pas illégal. À la reprise des interrogatoires, Charland réitère à nouveau que tout ce qu’il a dit sur Fecteau est vrai, mais que toutes les informations qui suivent sur Laplante sont fausses.

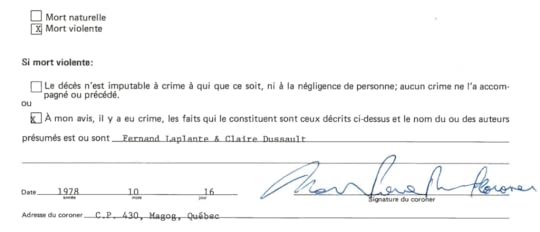

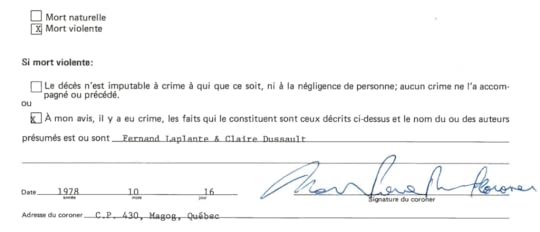

Claire Dussault-Laplante

Claire Dussault-LaplanteSans se laisser décourager par ces éclats – qui étaient clairement un parjure – le tribunal a continué et le coroner Rivard a allègrement appelé son prochain témoin, Claire Dussault, 20 ans. Laplante et Dussault ne se sont mariés que récemment cet été-là. La scène au tribunal s’est répétée presque à l’identique de l’éruption de Charland. Claire Dussault-Laplante a commencé calmement en déclarant qu’elle connaissait Carole Fecteau depuis février 1978. Elle a raconté que peu de temps avant sa disparition, elle avait accompagné Fecteau pour ramasser du haschisch. Le questionnement se tourna ensuite vers Fernand Laplante. Dussault-Laplante a été persuadée de dire que son mari avait fait un voyage à Coaticook, près du site où le corps de Fecteau a été découvert à East Hereford. À ce stade, Claire Dussault a interrompu son témoignage, affirmant que tout était faux, et comment elle avait été agressée et battue par la police pour avoir fait de fausses déclarations (frapper un témoin sous interrogatoire est illégal).

À la suite de cette deuxième interruption de la cour kangourou de Rivard, le coroner a immédiatement ajourné l’enquête jusqu’au 15 septembre, vraisemblablement pour que la police puisse administrer une persuasion supplémentaire de leur témoin vedette, Jean Charland. Rappelons que lorsque la colocataire de Carole Fecteau a été interrogée, Hélène Larochelle a mentionné que Fecteau avait peur de deux personnes qu’elle appelait « Claire et Fern ». On peut présumer qu’elle voulait dire Claire Dussault et Fernand Laplante, mais on se demande maintenant à quel point Larochelle a été «coachée» par la police pour donner cette réponse, étant donné que Dussault et Charland ont refusé de témoigner parce qu’ils estimaient que leur témoignage avait été contraint par la police. Comme nous le verrons, il s’agissait d’une tendance à la Sûreté du Québec des Cantons qui remet en question toutes leurs enquêtes de cette époque.

Trois semaines plus tard, lorsque l’enquête a repris, Charland n’apparaissait plus sûr de ses déclarations. Il parla d’une Oldsmobile qu’il avait vendue à Laplante et de la Cadillac de Raymond Grimard qu’ils avaient utilisée pour se rendre à Montréal. Il s’agit assurément de la Cadillac retrouvée au Golf de Lennoxville, immatriculée sous le nom de sa petite amie, Manon Bergeron. La plupart du temps, Charland a juste déclaré qu’il ne savait pas très “beaucoup”, ou qu’il ne se souvenait de “rien”. Peu importe l’amnésie soudaine de Charland, la SQ trouvera bientôt une méthode pour s’assurer qu’il se souvienne.

Claire Dussault a été rappelée pour témoigner, mais ses déclarations n’étaient qu’une répétition de sa première comparution : bavardage, mais peu de détails incriminants. Elle a évoqué un incident survenu début juillet devant le Moulin Rouge où elle a accidentellement reculé la voiture qu’elle conduisait dans une moto appartenant aux Gitans. Après son mariage avec Fernand le 14 juillet, le couple passe la majeure partie de son temps à St-Denis-de-Brompton jusqu’à l’arrestation de son mari le 3 août à Montréal. Toutes les informations qu’elle avait fournies aux agents sur l’implication de Fernand Laplante dans les meurtres de Fecteau, Grimard et Bergeron étaient toutes du “blabla” et “un tas de mensonges” qu’elle a dit aux enquêteurs parce qu’elle avait été agressée et battue par eux.

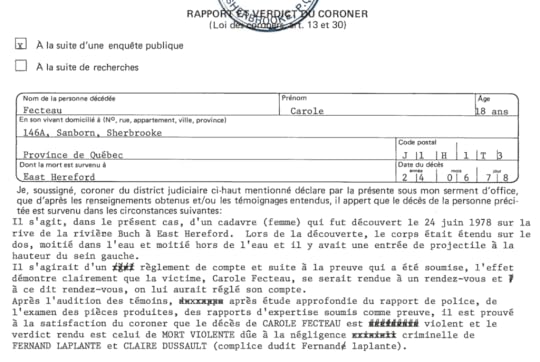

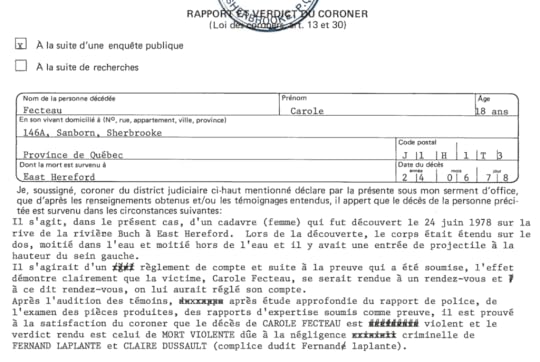

Prouvé à la satisfaction du coronerLe 16 octobre 1978, le coroner Jean-Pierre Rivard tient Fernand Laplante criminellement responsable des morts violentes de Raymond Grimard et Manon Bergeron, et de Carole Fecteau. À la fin de décembre 1978, Laplante a été inculpé de trois chefs de meurtre au premier degré, avec un procès prévu pour janvier 1979. S’il est reconnu coupable, Laplante encourt une peine d’emprisonnement à perpétuité.

Coroner verdict – Carole Fecteau

Coroner verdict – Carole Fecteau Jean-Pierre Rivard’s determination for Carole Fecteau dated August 16, 1978

Jean-Pierre Rivard’s determination for Carole Fecteau dated August 16, 1978Quand on regarde les verdicts officiels du coroner Jean-Pierre Rivard pour les trois meurtres en date du 16 octobre 1978, ce qui frappe, c’est l’uniformité des trois documents. Ils auraient presque pu être réalisés avec du papier carbone en triple exemplaire. Trois meurtres distincts à deux endroits différents à deux moments différents. Deux victimes abattues, une matraquée et étranglée à mort; pourtant une seule partie responsable.

C’était une ruée vers le jugement. Le coroner et la police ont tiré à la hâte et de manière agressive la conclusion qu’un seul homme était responsable de toutes les violences inhabituelles qui ont eu lieu au cours de quelques week-ends en juin et juillet 1978. Les preuves indiquaient clairement plusieurs parties impliquées. Il y avait déjà des preuves d’une pègre criminelle qui travaillait en groupes; le saccage de l’hôtel en janvier, l’affaire de la banque à Hatley deux jours avant les meurtres de Grimard et de Bergeron, Fecteau vendant de la drogue pour Charland et Grimard. Pourtant, il a été « prouvé à la satisfaction » du coroner que Fernand Laplante était le seul coupable.

À la fin de l’année, Jean-Pierre Rivard annonce de manière inattendue qu’il quitte ses fonctions de coroner à compter du 31 décembre 1978. Rivard qualifie le travail du coroner « d’ingrat », et dans son annonce, La Tribune rappelle au public que « un coroner travaille toujours dans les coulisses de la mort ». Peut-être un reproche à Rivard – et à ceux qui tiraient ses ficelles – qu’il était devenu trop le centre d’attention. Un coroner au Québec était souvent un avocat, rarement un professionnel de la santé. Rivard n’était ni l’un ni l’autre, apprenant le métier alors qu’il était notaire professionnel avant de sombrer dans l’obscurité.

Il y a quelques années, j’ai eu le plaisir de m’entretenir avec le criminologue québécois, Jean Claude Bernheim. Il m’a dit qu’à l’époque des années 1970, le coroner travaillait avec les forces de police et que le coroner “ne prenait pas de décisions sur des faits mais dans l’intérêt de la police”. Il a dit que lorsque des policiers étaient impliqués dans une affaire, le coroner prenait toujours du côté des forces de l’ordre : « Si vous ne répondez pas au coroner, vous pouvez être tenu responsable et votre témoignage peut être utilisé contre vous.” Je lui ai demandé s’il était possible pour un coroner de mentir dans l’intérêt de la police, et Bernheim a répondu : « Entièrement ».

Payé cher

Ce qui a agité la police plus que tout dans tout ce processus, c’est le refus inébranlable de Laplante de jouer son rôle de bouc émissaire dans un résultat prédéterminé. Laplante ne témoignera pas à l’enquête du coroner de Rivard, même s’il est assigné à le faire. Lors des témoignages de sa femme et de Charland, il a crié devant le tribunal que “il ne savait rien, ne savait pas pourquoi il était là et avant de monter à bord, il voulait savoir ce qu’on avait dit sur lui en son absence”. Non seulement le coroner Rivard a déclaré Laplante criminellement responsable des trois meurtres et apte à subir son procès, mais il a cité Laplante pour outrage au tribunal et l’a condamné à un an de prison pour avoir refusé de témoigner lors de son enquête. Quinze ans plus tard, alors que Laplante faisait appel de son verdict de culpabilité pour les meurtres de Grimard et de Bergeron, Fernand Laplante, contrit, purgeant alors sa peine à perpétuité dans un pénitencier des Maritimes, dit avoir « payé cher son manque de coopération ». J’ai sauté sur ce que vous auriez tous dû deviner, mais le verdict de culpabilité de Laplante a été l’élément le moins surprenant de son procès, comme nous le verrons bientôt.

C’est ce qui vous brise le cœur, mais essuyez vos larmes et concentrez votre attention sur un détail important. La peine d’un an de Rivard pour outrage a eu lieu en octobre 1978. Cela signifie que Laplante a été en prison tout le mois de novembre 1978. Il n’a donc pu jouer aucun rôle dans le meurtre de Theresa Allore ou sa disparition le 3 novembre 1978.

Mais quelqu’un était libre et opérait dans la communauté sherbrookoise en novembre 1978. L’homme qui a pointé du doigt a Laplante: Jean Charland.

The post Les trois meurtres: avenues sans fin first appeared on Who Killed Theresa?.

April 23, 2022

Three of a Perfect Pair

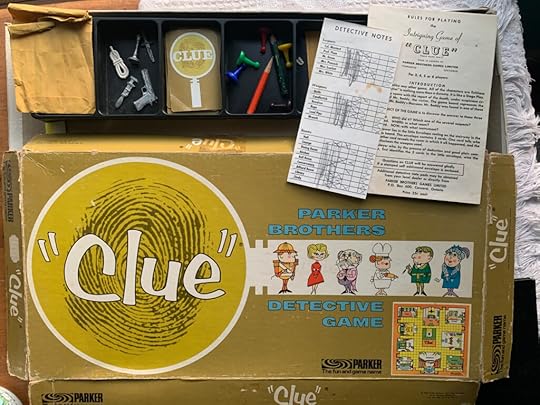

Have you ever played Clue? This is a detective game that asks participants to discover the murderer, the location, and the murder weapon. The results can be:

“Miss White did it in the library with the candlestick!” or “I accuse Colonel Mustard of the murder; he did it in the kitchen with a knife!” or “I suspect Miss Scarlett, in the lobby, with the revolver!” and so on.

In the coroner’s inquest into the murder of Carole Fecteau and those of Raymond Grimard and Manon Bergeron, one sometimes has the impression of being at the heart of an enigma where the avenues seem endless because of the many twists and turns.

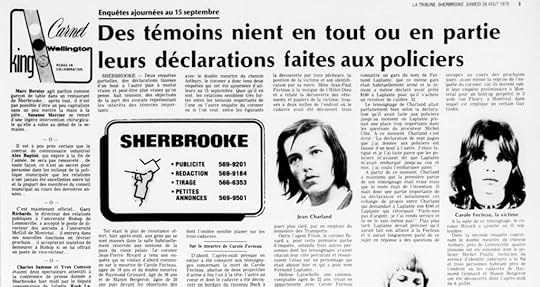

“Les trois meurtres: avenues sans fin”, La Tribune, 16 Septembre, 1978

“Les trois meurtres: avenues sans fin”, La Tribune, 16 Septembre, 1978

“Les trois meurtres: avenues sans fin”, La Tribune, 16 Septembre, 1978Reach back and recall the opening of Patricia Pearson’s series in the National Post, Who Killed Theresa?” Her first sentence was, “We tend to think of unsolved mysteries as a parlour game.” 24 years earlier, Sherbrooke 1978, the editors of La Tribune were likening the murders of Grimard, Bergeron and Fecteau to a game of Clue. Why care about these small-time hoods and drug peddlers? Because they may hold the key to solving your greatest personal mystery – the one you cannot solve is the one that keeps your heart from mending. The one that propels you and keeps you halted in place and time.

Our family’s game of ClueCalisse de merde

Our family’s game of ClueCalisse de merdeIn his infinite wisdom, coroner Jean-Pierre Rivard decided his inquiry would be a three-fer: the murder inquests of Raymond Grimard, Manon Bergeron and Carole Fecteau would all be done together. Whether this was done for thrift and expedience, or under pressure from police is unknown, but the result the creation of a gordian knot of confusion, it was hard to separate the “twists and turns” of all the testimonies and determine what information belonged with what potential criminal process. How do you argue three at once, if the whole purpose of the coroner process is to determine whether or not a criminal act was actually even committed, and by whom? What if the conclusion is three different assassins? Coroner Rivard had an answer for that too. His process had already pre-determined the identity of the guilty party: Fernand Laplante.

Fernand Laplante

Fernand LaplanteBy now you should be all wondering, who was this Fernand Laplante? He wasn’t any mother nature’s son. Laplante certainly was no stranger to the Sherbrooke criminal underworld. In 1965, at the age of 20 he served a six month sentence at St. Vincent de Paul penitentiary for the burglary of a Coaticook garage. In 1969 he received another two years for breaking and entering. Apparently the charge never stuck. In 1970 Laplante and his partner, Gaston Brochu were caught red-handed with $27,000 worth of mens clothing from a Magog haberdashery stashed in the trucks of their cars. In 1971 he attempted to burgle the home of a small arms collector, again in Magog. By 1974 Laplante had racked up fifteen convictions when he was again arrested for attempting to steal a safe from the Felix market in Sherbrooke. Robbery, burglary, breaking and entry; but not murder.

After the July 1978 attempted bank heist in Hatley (to which Laplante was a party along with Jean Charland), and the murders of Grimard and Bergeron which quickly followed two days later, police arrested Laplante on August 3rd in Montreal during another attempted hold-up. Someone who worked closely on the cases of Grimard and Bergeron told me police suspected Laplante of committing murders in his past, but not these murders, “It didn’t matter that he hadn’t killed Grimard and Bergeron – they wanted him so badly.”

Jean-Pierre Rivard began his coroner’s inquest in late August 1978. The star witness was Jean Charland. At first, Charland’s testimony went smoothly. He told the court how he was unemployed, how Carole Fecteau was his little brother’s girlfriend and that he had seen Fecteau two or three times “at the most”, and how he and his brother and “two other guys” had stolen Hélène Larochelle’s vehicle (Fecteau’s roommate).

Charland à gauche, Rivard à droite

Charland à gauche, Rivard à droiteWhen questioning turned to Fernand Laplante things became strange. Charland stated that he knew the guy, that he was usually armed, and that he had lent Laplante $160 so he could buy a .32 caliber revolver. When prosecutor Michel Côte continued to press Jean Charland about Fernand Laplante, Charland suddenly cried out, “the seven-page statement I gave to the police is false from one end to the other. I was tired and I made it because the police had told me that Laplante had taken me in, up to my neck and I wanted to take him in too!”

For the uninitiated, what Charland meant was that police told Charland that Leplante had blamed him for the murders, so then Charland turned on Laplante and said that it was in fact he who killed the three victims. Lying to a witness during a police interrogation is generally frowned upon because there is no scientific evidence that the technique produces results, but it is not illegal. When questioning resumed, Charland again reiterated that everything he had said about Fecteau was true, but that all the information that came after it about Laplante was false.

Claire Dussault-Laplante

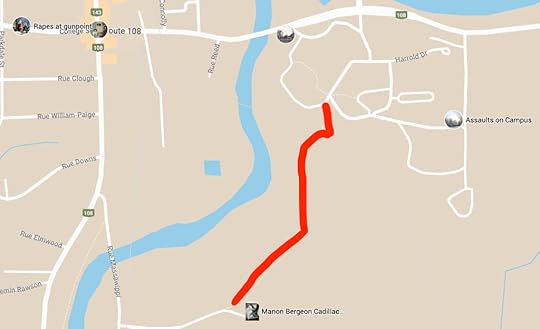

Claire Dussault-LaplanteUndeterred by these outbursts – which was clearly perjury – the court continued, and Coroner Rivard blithely called his next witness, 20-year-old Claire Dussault. Laplante and Dussault were only recently married that summer. The scene in court was repeated almost identical to Charland’s eruption. Claire Dussault-Laplante started calmly, stating she had known Carole Fecteau since February, 1978. She talked of how shortly before her disappearance, she accompanied Fecteau to pick up some hashish. The questioning then turned to Fernand Laplante. Dussault-Laplante was coaxed to say that her husband had taken a trip to Coaticook, near the site where Fecteau’s body was discovered in East Hereford. At this point Claire Dussault cut off her testimony, saying it was all false, and how she had been molested and beaten by police into giving false statements (striking a witness under interrogation is illegal).

Following this second interruption of Rivard’s kangaroo court, the coroner immediately adjourned the inquiry until September 15, presumably so that police could administer some additional persuading of their star witness, Jean Charland. Recall that when Carole Fecteau’s roommate was questioned, Hélène Larochelle mentioned that Fecteau was fearful of two people she referred to as “Claire and Fern”. We can surmise that she meant Claire Dussault and Fernand Laplante, but one now wonders how much Larochelle was “coached” by police into giving this answer, given that both Dussault and Charland refused to testify because they felt their testimony had been coerced by police. As we shall see, this was a pattern with the Townships Sûreté du Québec that calls into question all of their investigations from this era.

Three weeks later when the inquest resumed, Charland didn’t appear any more sure of his statements. He talked of an Oldsmobile he had sold to Laplante, and of Raymond Grimard’s Cadillac, which they had used to go to Montreal. This was most assuredly the Cadillac found at the Lennoxville Golf Course, registered under his girlfriend’s name, Manon Bergeron. Mostly Charland just stated that he didn’t know very “much”, or he didn’t remember “anything”. Never mind Charland’s sudden amnesia, the SQ would soon come up with a method to make sure he remembered.

Claire Dussault was called back to testify, but her statements were a repeat of her first appearance: small talk, but few incriminating details. She spoke of an incident that occurred in early July outside the Moulin Rouge where she accidentally backed the car she was driving into a motorcycle belonging to the Gitans. After her marriage to Fernand on July 14, the couple spent most of their time in St-Denis-de-Brompton until her husband’s arrest on August 3 in Montreal. Any of the information she had provided to officers about Fernand Laplante’s involvement in the murders of Fecteau, Grimard and Bergeron was all “blabbering” and “a bunch of lies” she told investigators because she was molested and beaten by them.

Proven to the satisfaction of the coronerOn October 16, 1978 Coroner Jean-Pierre Rivard held Fernand Laplante criminally responsible for the violent deaths of Raymond Grimard and Manon Bergeron, and Carole Fecteau. In late December 1978, Laplante was charged with three counts of first-degree murder, with a trial set for January 1979. If found guilty, Laplante faced a sentence of life imprisonment.

Coroner verdict – Carole Fecteau

Coroner verdict – Carole Fecteau Jean-Pierre Rivard’s determination for Carole Fecteau dated August 16, 1978

Jean-Pierre Rivard’s determination for Carole Fecteau dated August 16, 1978When you look at Coroner Jean-Pierre Rivard’s official verdicts for all three murders, all dated October 16, 1978, what strikes you is the uniformity of all three documents. They could have almost been done using carbon paper in triplicate. Three distinct murders in two different places at two different times. Two victims shot, one bludgeoned and strangled to death; yet only one party responsible.

It was a sprint to judgement. The coroner and police hastily and aggressively drew the conclusion that only one man was responsible for all the uncharacteristic violence that took place over the course of a couple of weekends in June and July 1978. The evidence was clearly pointing to several parties involved. There was already evidence of a criminal underworld that worked in groups; the hotel shakedown in January, the casing of the bank in Hatley two days before the Grimard and Bergeron murders, Fecteau selling drugs for both Charland and Grimard. Yet it was “proven to the satisfaction” of the coroner that Fernand Laplante was the only guilty party.

At the close of the year, Jean-Pierre Rivard unexpectedly announced that he was stepping down as coroner effective December 31, 1978. Rivard called the work of the coroner, “thankless”, and in its announcement, La Tribune reminded the public that “a coroner always works behind the scenes of death”. Perhaps a rebuke to Rivard – and the ones pulling his strings – that he had become too much the focus of attention. A coroner in Quebec was often a lawyer, rarely a medical professional. Rivard was neither, learning the trade while a professional notary before fading into obscurity.

A few years ago, I had the pleasure of speaking with the Quebec criminologist, Jean Claude Bernheim. He told me in the era of the 1970s the coroner worked with police forces, and that the coroner, “made decisions not on facts but in the interests of the police.” He said that when police officers were involved in a case the coroner always took the side of law enforcement: “If you don’t respond to the coroner, you can be held responsible, and your testimony can be used against you.” I asked him if it were possible for a coroner to lie in the interests of the police, and Bernheim responded immediately, “Fully”.

Paid dearly

What agitated police more than anything in this entire process was Laplante’s steadfast refusal to play his part as the fall-guy in a preordained outcome. Laplante would not testify at Rivard’s coroner’s inquest, even though he was subpoenaed to do so. During the testimonies by his wife and Charland, he shouted in court that “he did not know anything, did not know why he was there and before he went on board, he wanted to know what had been said about him in his absence”. Not only did Coroner Rivard declare Laplante criminally responsible for all three murders and fit to stand trial, he cited Laplante with contempt of court and sentenced him to one year in jail for refusing to testify at his inquest. Fifteen years later when Laplante was appealing his guilty verdict for the Grimard and Bergeron murders, a contrite Fernand Laplante, then serving his life sentence in a Maritime penitentiary, said he “had paid dearly for his lack of cooperation.” I’ve skipped ahead to what you all should have guessed eventually occurred, but Laplante’s guilty verdict was the least surprising element of his trial, as we shall soon see.

It’s the stuff that breaks your heart, but wipe away your tears and focus your attention on one important detail. Rivard’s one year sentence for contempt occurred in October 1978. Meaning Laplante was in prison all through the month of November 1978. Therefore he could not have played any part in the murder of Theresa Allore, or her disappearance on November 3, 1978.

But someone was free and operating in the Sherbrooke community in November 1978. The man who fingered Laplante: Jean Charland.

The post Three of a Perfect Pair first appeared on Who Killed Theresa?.

April 16, 2022

Les meurtres de Raymond Grimard et Manon Bergeron

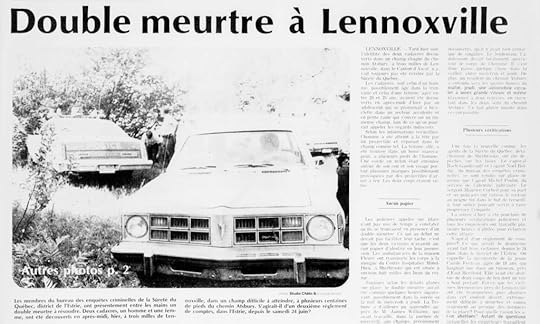

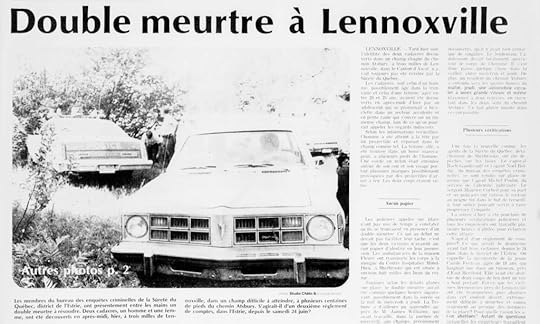

“Est-il possible de parler de bas-fonds à Sherbrooke et même d’oser avancer qu’une guerre ouverte y est déclarée? Se rait-il plus juste de dire que l ’ on est en train de procéder à un nettoyage en règle, motivé par la crainte ou la prudence, dans un milieu peu recommandable de la ville? Il est certain qu’il se passe des choses depuis le début de juin et ce qu ’ il est maintenant convenu d ’ appeler les deux règlements de comptes, celui du 24 juin et le double du 6 juillet, dénotent que certaines personnes ne se sentent pas bien dans leur peau et peut-être que d ’ autres craignent pour la leur”

“Indices d’un grand nettoyage dans un certain milieu louche?”, La Tribune, 8 Juillet, 1978

S-Town – Je ne parle pas de Woodstock, Alabama. C’est ici même à Sherbrooke 1978 : S-Town, Sleaze-Town, Shit-Town. Ceci est, bien sûr, une référence voilée au podcast populaire des producteurs de Serial et This American Life, mais avant que quiconque ne s’offusque, j’aime Sherbrooke. Il y a une tendance à dégrader n’importe quel endroit de votre passé. L’ouest de l’île de Montréal était un dépotoir, Saint John, au Nouveau-Brunswick, était « le trou du cul du Canada ». Toronto a toujours eu un complexe d’infériorité, et Carrboro – où je vis actuellement – était une ville industrielle ‘podunk’ avant qu’elle ne soit envahie par les intellectuels universitaires. Chaque fois que je visite les Cantons-de-l’Est, j’essaie d’y voir un peu de lumière, car les ténèbres de son passé peuvent vous étouffer. Quand je suis à Compton, je commande le petit-déjeuner et écume le JdM au même restaurant, à chaque fois, et je ne dis jamais qui je suis ni ce qui m’a amené là-bas. Lorsque Patricia Pearson et moi avons visité il y a quelques années, en faisant des recherches pour notre livre, nous nous sommes assurés de réserver du temps pour de bonnes choses, comme la Fromagerie La Station. Vous devez investir du temps pour voir le bien, “kick at the darkness ’til it bleeds daylight.”

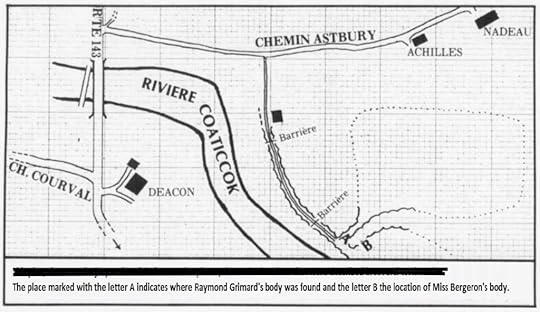

The darknessDans l’après-midi du jeudi 6 juillet 1978, le lycéen Alain Boulanger conduisait sa motocyclette sur les sentiers secondaires au sud de Lennoxville lorsqu’il a aperçu un homme allongé sur le sol au large du chemin Astbury, près de la route 143, et à environ 11 kilomètres au sud de Sherbrooke . Alarmé, Boulanger rentra chez lui pour le dire à sa mère. Et c’est ainsi que vous savez que vous êtes arrivé à S-Town; la mère a immédiatement informé son enfant de retourner vérifier si l’homme était mort.

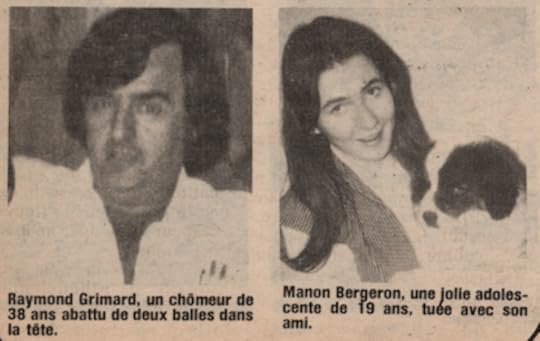

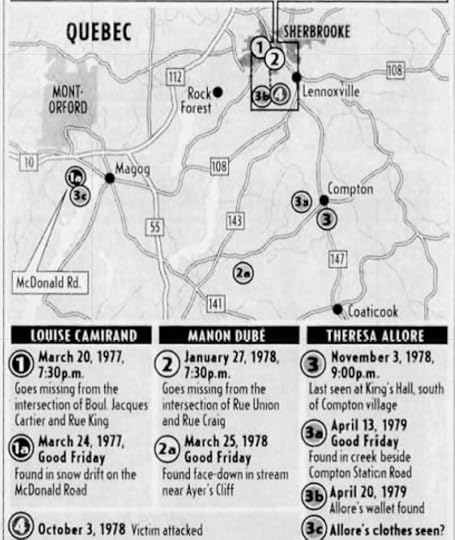

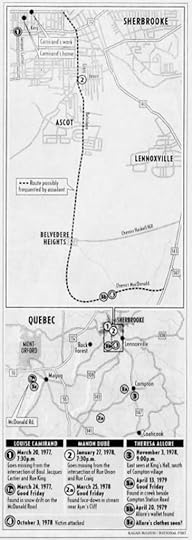

L’enquête dans ce dossier a été menée par le sergent Marcoux assisté des détectives Réal Châteauneuf (de l’affaire Fecteau), Noël Bolduc et Roch Gaudreault du bureau des enquêtes criminelles de la division des Cantons-de-l’Est de la Sûreté du Québec. Le gendarme Michel Poulin de la SQ est arrivé le premier sur les lieux. L’homme gisait dans un pâturage et avait été abattu de neuf balles. À environ 20 mètres de l’homme, la police a découvert le corps d’une femme. Au début, ils pensaient qu’elle aussi avait été abattue, tant le traumatisme crânien était grave. Après un examen plus approfondi, la police a découvert qu’elle avait été battue, peut-être avec la crosse d’un fusil, et étranglée par une corde qui lui restait encore autour du cou (rappelons que Louise Camirand avait aussi une corde autour du cou).

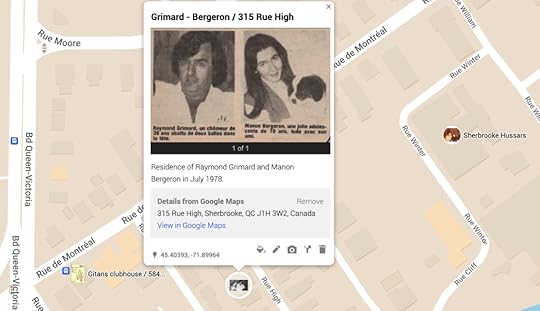

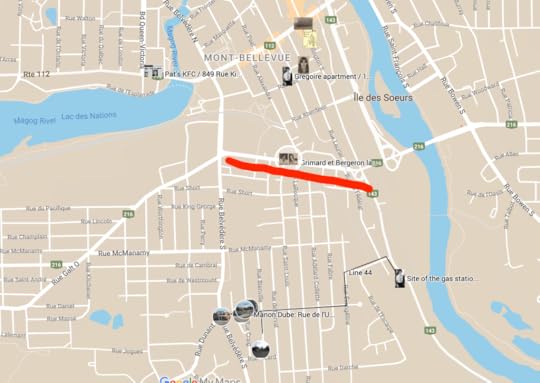

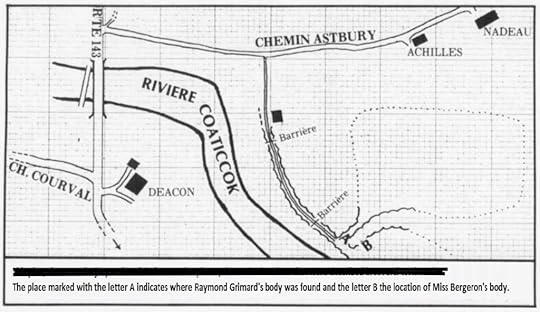

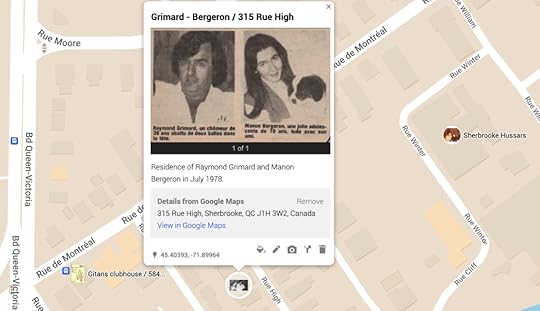

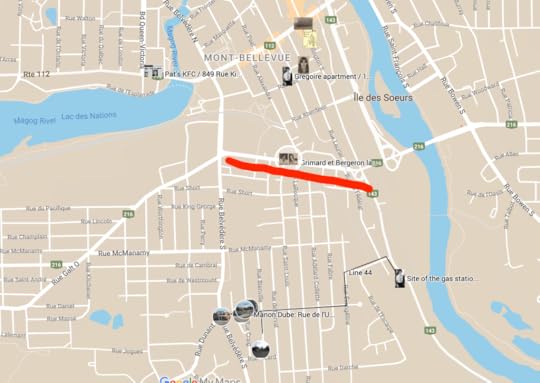

À environ 7 kilomètres au nord du terrain de golf de Lennoxville, la police a rapidement découvert une Cadillac 1970 abandonnée immatriculée au nom de Manon Bergeron du 325 rue High à Sherbrooke. À partir de là, la police a pu déterminer que les corps dans le pâturage au sud de Lennoxville étaient Manon Bergeron, 20 ans, et son petit ami de 38 ans, Raymond Grimard (pour une visualisation géographique des emplacements, veuillez visiter cette carte Google).

Des autopsies ont été pratiquées le 8 juillet. Le médecin légiste a estimé que Grimard et Bergeron étaient morts depuis environ 48 heures, mais pas plus de 72 heures. Grimard a été abattu avec un fusil de calibre 0,22; quatre fois à l’arrière de la tête, deux fois à l’avant du corps, une fois à l’épaule gauche, une fois à la cuisse gauche et une fois à l’index de la main gauche. Bergeron avait six blessures à l’arrière de la tête, causées par un objet contondant. Grimard est décédé des multiples fractures du crâne à la tête. Le pathologiste a déclaré que Bergeron aurait pu être tué par un traumatisme contondant, ou par asphyxie, ou les deux. Aucune douille n’a été récupérée sur le site de la route d’Astbury, ni leurs quantités importantes de sang dans le pâturage, ce qui signifie que les scènes de crime se trouvaient ailleurs; Grimard et Bergeron n’ont pas été assassinés au sud de Lennoxville.

Voici Les MonstresRaymond Grimard était bien connu des services de police et avait eu plusieurs « démêlés avec la justice ». Connu sous le nom de « Le Loup », Grimard vivait avec Manon Bergeron dans l’appartement de la rue High. Il était situé à égale distance du quartier général des Gitans sur la rue Montréal et du quartier général des Sherbrooke Hussars sur Winter, chacun à distance de marche.

Grimard /Bergeron apartment at 315 Rue High

Grimard /Bergeron apartment at 315 Rue High

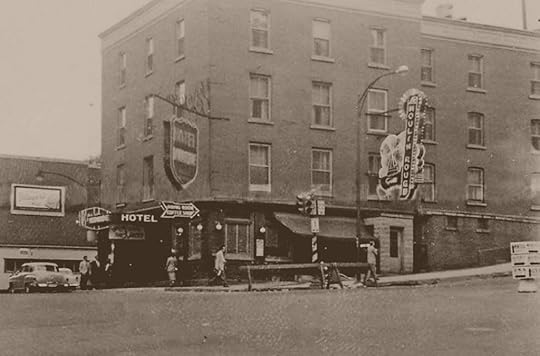

Raymond Grimard était un ancien serveur de l’Hôtel Normandie, mieux connu sous le nom de Moulin Rouge au coin King et Wellington au centre-ville de Sherbrooke. Manon Bergeron travaillait comme barmaid dans des établissements similaires. Grimard et Bergeron ont été vus dans la Cadillac par plusieurs témoins roulant dans le couloir King et Wellington le soir du 5 juillet. Le beau-frère de Bergeron, Guy Robert aurait été la dernière personne à avoir vu le couple vivant, accompagné des enfants de Grimard, à une maison de la rue Galt vers 0 h 20, le 6 juillet 1978.

Galt, High, King, Wellington : notre carte devient assez encombrée. À propos de High Street et de l’appartement où Grimard habitait avec Bergeron, un auditeur écrit : « J’ai habité High Street de 75 à 77. Un quartier horrible à vivre. J’ai déménagé le matin où la police est venue frapper à ma porte et m’a dit que ma voisine, ma propriétaire qui avait 86 ans et était aveugle… avait été battue la nuit précédente. Elle est décédée un jour plus tard. J’ai été harcelé tout le temps et je ne me suis jamais senti en sécurité. Les motards sur le bien-être accroché sur la rue jour et nuit.

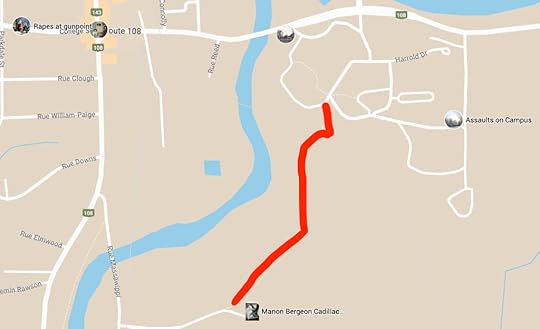

La rue Galt, où ils ont été vus pour la dernière fois, est intéressante, séparant le quartier de la classe ouvrière où Manon Dubé vivait du paysage urbain plus rude de King et Wellington où Bergeron et Grimard “travaillaient” ostensiblement, même si je dirais que Grimard n’a probablement jamais travaillé un jour légitime de son la vie, optant pour des missions contractuelles et le trafic de drogue « sous la table ». Ensuite, il y a là où ils ont été trouvés, ou mieux, là où la Cadillac de Bergeron a été retrouvée, dans le terrain de gravier du Golf de Lennoxville. J’ai tracé pour vous avec une ligne rouge le sentier pédestre qui mène du cours d’or au collège Champlain. C’est le tristement célèbre chemin où depuis plus de 40 ans les élèves se plaignent d’agressions sexuelles, et l’école a refusé de l’éclairer. Je sais que nous avons dit que la zone est petite, et cela ne veut peut-être rien dire, mais notre petit monde du crime devient vraiment très petit.

Où ils vivaient, où ils travaillaient, où ils ont été vus pour la dernière fois, où ils ont été trouvés ; pour moi, il est juste fondamental que vous vouliez savoir ces choses. Récemment, l’unité des affaires non résolues de la Sûreté du Québec s’est vantée d’avoir finalement voyagé dans les Cantons-de-l’Est et visité l’endroit où Theresa a été vue pour la dernière fois, où elle a vécu, où elle a été retrouvée, où son portefeuille a été retrouvé. Ils étaient visiblement très fiers de l’accomplissement. Leur unité existe depuis 2004; J’ai du mal à comprendre pourquoi il leur a fallu 18 ans pour faire ça. Ils m’ont également mentionné à trois reprises au cours des quatre derniers mois comment, en 1979, après la découverte du corps de Theresa, ils ont tenu une mairie à Compton et interviewé pratiquement tous les membres de la communauté. Et c’est super. Mais le fait est qu’ils avaient à ce moment-là 4 meurtres et 1 mort suspecte tous dans leur quartier Estrie, la majorité avec des liens vers le nord près de Sherbrooke, la majorité avec des associations et des inter-associations avec le corridor King et Wellington. Ils auraient dû concentrer leurs efforts là-bas, les gens de Compton n’en savaient rien.

L’Informateur

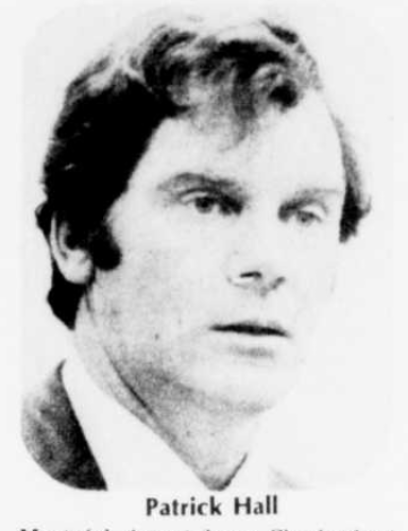

L’InformateurComme pour Carole Fecteau dont le corps avait été retrouvé 12 jours plus tôt à East Hereford, Grimard et Bergeron avaient été dépouillés de leurs papiers d’identité. Lorsque l’agent de la Sûreté du Québec, Réal Châteauneuf, est arrivé sur le site du chemin Astbury, il a trouvé 19 $ et un morceau de papier sur le corps de Grimard. Le papier contenait un numéro de téléphone et le nom « Tricia Hall ». Le numéro de téléphone correspondait à celui du quartier général local de la Sûreté du Québec, un certain Patrick Hall était détective au sein de ce détachement.

De cette information, on a supposé que Raymond Grimard, “Le Loup” de la pègre sherbrookoise, s’était transformé et travaillait maintenant comme informateur de la police. L’agent Réal Châteauneuf révélera plus tard que le 4 juillet, la police avait surveillé Grimard et plusieurs membres de son équipage et avait suivi un certain nombre de voitures et de motos de Sherbrooke à North Hatley. Le groupe a passé environ une demi-heure à caser une banque dans le village sous l’œil attentif de la SQ. La police a soupçonné que le gang prévoyait un hold-up, mais a annulé les choses lorsqu’ils ont commencé à soupçonner qu’ils étaient surveillés. Le cadre comprenait Raymond Grimard, Jean Charland, Mario Vallières et Fernand Laplante.