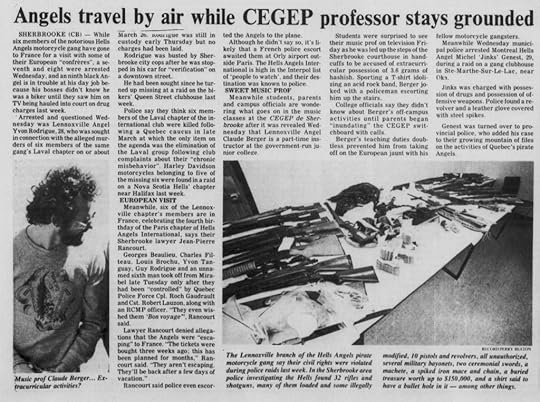

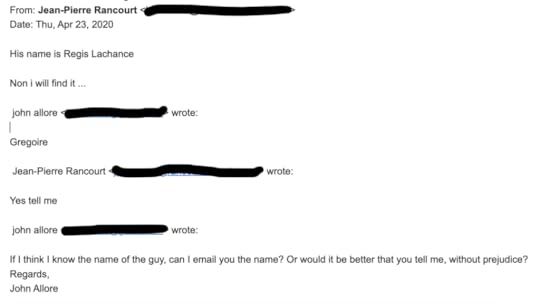

John Allore's Blog, page 4

May 30, 2022

Justice muselée

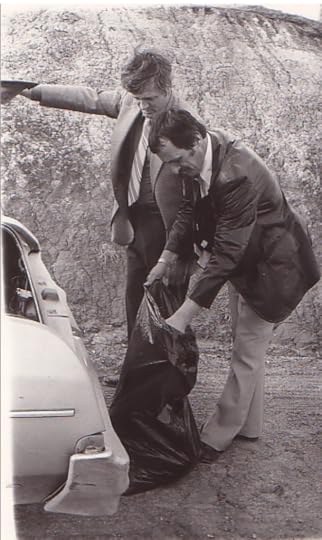

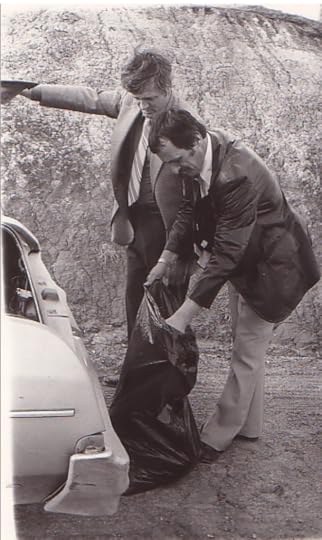

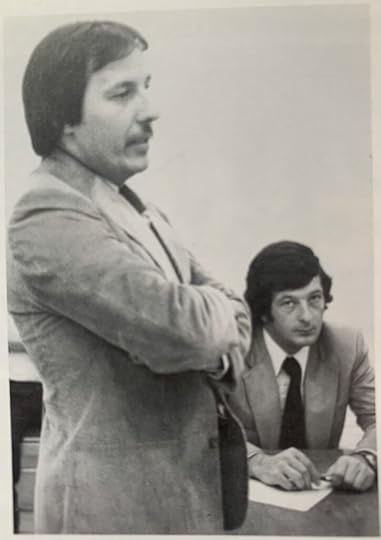

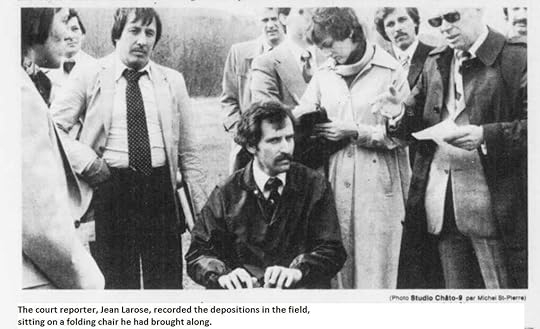

Il y a une photo de l’agent de la Sûreté du Québec, Jacques Filion, regardant dans un sac poubelle de vêtements au dépotoir de ma sœur le matin où elle a été retrouvée, le 13 avril 1979. Roch Gaudreault est avec lui, faisant semblant de regarder dans le sac en plastique. Wish You Were Here a l’agent identifié à tort comme Jacques Lessard, mais c’est Filion, le gars de l’affaire Fecteau. Filion est l’agent qui a récupéré les vêtements de Carole.

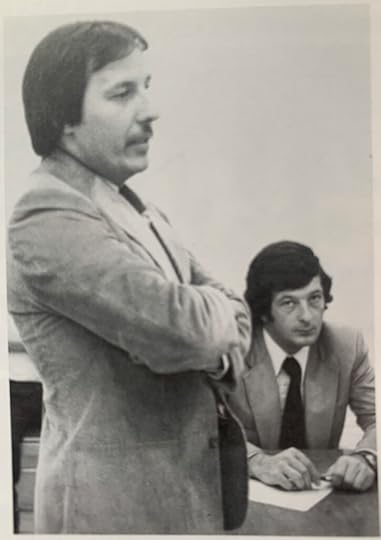

Roch Gaudreault et Jacques Filion

Roch Gaudreault et Jacques FilionIl y a une deuxième photo de ce matin – Vendredi saint 13 avril 1979 – les deux agents debout à côté d’un arbre où gisait le corps de Theresa, faisant semblant d’avoir une conversation. Les photos sont mises en scène ; les détectives ne font vraiment rien, ils n’enquêtent pas vraiment.

Jacques Filion et Roch Gaudreault

Jacques Filion et Roch GaudreaultIl n’a jamais été déterminé qui portait des vêtements dans ce sac. Ce n’était pas celui de Thérèse. Était-ce celui de Fecteau ? Pas les vêtements qu’elle portait, Filion les a trouvés. Et s’il s’agissait de vêtements laissés à son jeune copain, Marc Charland ? Et si, à peu près au moment où l’agent Réal Châteauneuf avait trouvé cette bûche de bouleau criblée de balles sous l’escalier du sous-sol chez les Charland, vers janvier 1979, son grand frère, Jean, avait remarqué les vêtements dans la chambre de Marc et avait dit à son petit frère : « Hé, tu dois te débarrasser de ce truc, tu as moins de 18 ans, tu ne veux pas que les flics pensent que tu as quelque chose à voir avec son tir.”

Alors Jean Charland a rassemblé toutes les affaires de Fecteau, les a mises dans un sac à ordures et les a abandonnées, mais juste pour rire, juste pour déconner avec la police, il les a jetées sur le site où il a su plus tard ce printemps-là que la neige fondait, ils allaient pour trouver une autre fille morte. Une blague, non ? Parce que Jean Charland savait que la police n’allait pas jouer avec lui, un homme créé. Alors, quand Jacques Filion a regardé dans ce sac poubelle, le vendredi 13 avril 1979, et qu’il a vu ce vêtement, savait-il à ce moment-là, à la veille du procès de Fernand Laplante pour deux meurtres qu’il n’avait pas commis, que la Sûreté du Le Québec manquait la vue d’ensemble? Qu’ils avaient un sérieux problème avec un meurtre sexuel ?

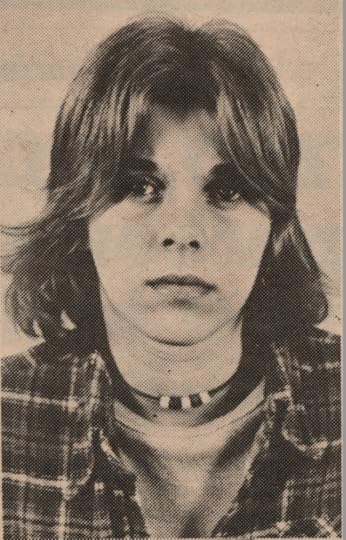

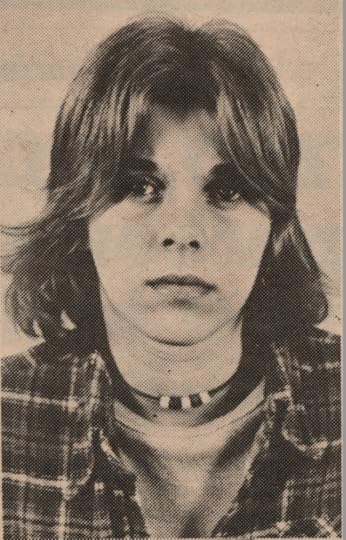

People will hold us to blame Carole Fecteau

Carole FecteauPremière assassinée, Carole Fecteau sera la dernière à avoir sa journée devant le tribunal. Encore une fois, la police a décidé de faire le procès de Fernand Laplante, et personne d’autre. Encore une fois, Laplante a été assisté par l’avocat de la défense, Jean-Pierre Rancourt, qui a remporté une requête pour déplacer le processus à Cowansville, à environ 100 kilomètres à l’ouest de Sherbrooke, en raison de la publicité excessive lors du premier procès de Laplante. La Couronne était à nouveau représentée par Claude Melancon, et les deux avocats ont accepté d’inclure plusieurs admissions des procès pour meurtre Grimard et Bergeron dans le but d’éviter la redondance et d’accélérer le processus judiciaire – cela allait être un coup de hache rapide.

L’affaire Fecteau s’est ouverte le lundi 19 novembre 1979. Jacques Mongeau a témoigné comment lui et un ami étaient allés pêcher dans un ruisseau près d’East Hereford le 24 juin 1978 et avaient découvert le corps nu d’une jeune femme qui était « blanche, ne respirait pas et semblait avoir des vers qui sortaient de sa peau.” Un employé des travaux publics de la province a alors pris la parole pour dire que le 26 juin, il avait trouvé un portefeuille, « au bord d’une route de gravier », courant vers East Hereford. Avant d’apporter le portefeuille à la police, l’homme a enflammé un arbre avec une hache pour marquer l’endroit où le portefeuille a été trouvé.

Buck Creek in East Hereford, where Carole Fecteau was found

Buck Creek in East Hereford, where Carole Fecteau was foundUn expert médico-légal a déclaré au tribunal que Fecteau est décédée des suites de deux balles tirées d’une arme de poing, la première étant entrée dans la nuque à une distance d’environ six pieds, tandis que la seconde a pénétré dans son thorax, pénétrant le poumon et le cœur gauches, ce qui a aurait pu être tiré à bout portant. Il n’y avait aucune trace d’alcool dans le corps de Fecteau, et pour une raison quelconque, Fecteau n’a pas été testé pour la drogue. Cet expert a déclaré que Fecteau n’avait pas été sexuellement active 24 heures avant sa mort.

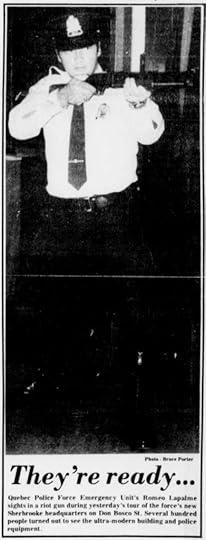

Jacques Filion

Jacques FilionLe photographe de la SQ Guimond Desbiens a témoigné comment il a pris des photos sur les lieux près d’East Hereford et a déclaré qu’il avait été frappé par les tatouages sur son corps, mais ne se souvenait pas avoir remarqué de noms. Michel Poulin, de la SQ, a déclaré avoir pris des photographies aériennes de la scène en janvier et octobre 1979, ainsi qu’une partie du secteur de la rue Wellington à Sherbrooke le 15 novembre.

C’est l’agent de la SQ Jacques Fillion qui s’est finalement retrouvé avec le portefeuille, et il a témoigné que ses vêtements; jeans, sous-vêtements et pull, ont été récupérés le même jour que son poncho déchiré à deux endroits différents sur la même route. À ce moment, Rancourt a demandé si Fillion était au courant que Marc et Jean Charland vivaient dans la région de Lennoxville au moment du crime, Fillion a confirmé qu’il était au courant.

Like any other candidateLe lendemain, The Sherbrooke Record rapportait cette curiosité :

« La majorité du témoignage d’hier dans le cas de Fernand Laplante, accusé de meurtre au premier degré dans la mort de Carole Fecteau à East Hereford le 20 juin 1978, a été consacrée au témoignage et au contre-interrogatoire d’un jeune homme. La presse notamment que envoyés par The Record s’interdisaient de mentionner son nom, son adresse, son âge, sa profession, ainsi que le prénom de son frère. Le juge Jean Louis Péloquin a également imposé d’autres restrictions concernant son témoignage.

“Judge sets press rules”, John McCaghey, Sherbrooke Record, November 22, 1979, page 3

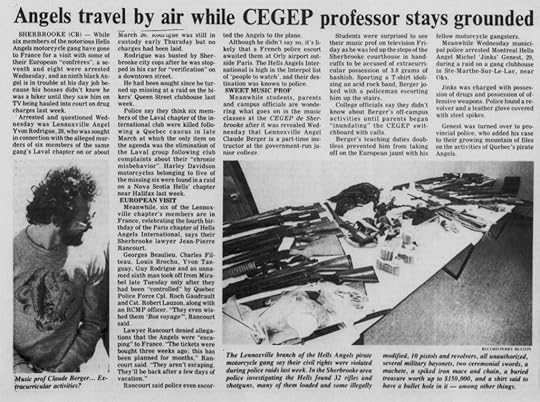

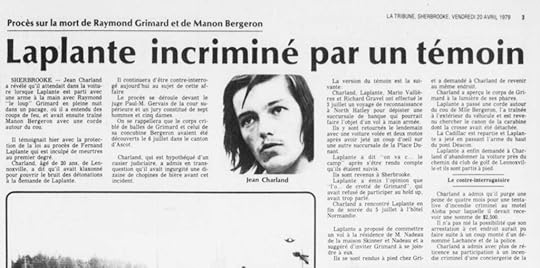

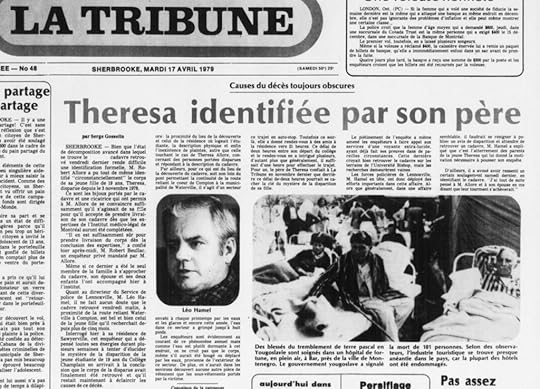

L’absence du principal journal français des Cantons, La Tribune, était tellement perceptible qu’elle a été dénoncée par la sœur des Cantons, la publication anglaise The Record. En fait, La Tribune a été portée disparue pendant les six premiers jours du procès. Le “jeune homme” que les tribunaux essayaient de “protéger” était plutôt évidemment le petit ami de Carole Fecteau, Marc Charland, et le prénom de son frère était Jean. Cependant, n’ayant pas été présent, La Tribune n’a jamais entendu l’interdiction de publication du tribunal, et a donc procédé à exposer le nom “Charland” tout au long de leurs reportages ultérieurs :

Sous la protection de la cour, le témoignage de Marc Charland était essentiellement une mini-version de l’histoire de Jean Charland dans le procès Grimard et Bergeron : il blâmait Fernand Laplante pour le meurtre de Carole Fecteau. Marc Charland a affirmé que Laplante lui avait dit un jour que Fecteau «était une garce et devait mourir». Puis le 20 juin 1978, le soir de la disparition de Fecteau, selon Charland, Laplante confie à nouveau que Fecteau « est morte, que son cas est réglé et qu’il l’a mise dans un ruisseau ». Apparemment, Fernand Laplante n’arrêtait pas de parler de Fecteau puisque le 21 juin dernier, Laplante, 34 ans, confiait encore à ce garçon de moins de 18 ans que Fecteau « avait des balles dans la tête et dans le cœur parce qu’elle avait envoyé deux mecs en prison ». En contre-interrogatoire, Marc Charland a atténué sa déclaration et a dit qu’il avait peut-être mal interprété les propos de Laplante. Le témoignage de Marc Charland était la principale preuve utilisée par la Couronne pour poursuivre Laplante.

Helen Larochelle

Helen LarochelleLe ministère public a ramené la colocataire de Fecteau, Hélène Larochelle, et en contre-interrogatoire, Jean Pierre Rancourt lui a fait admettre que peu de temps avant la disparition de Carole, le ou vers le 20 juin 1978, leur appartement a été visité par « deux frères qui doivent rester anonymes », mais que nous connaissons maintenant étaient Marc et Jean Charland. Fecteau a eu une dernière conversation téléphonique avec Johanne Tanguay à deux reprises, avant de quitter l’appartement vers 20h00 et de se diriger vers la rue Wellington.

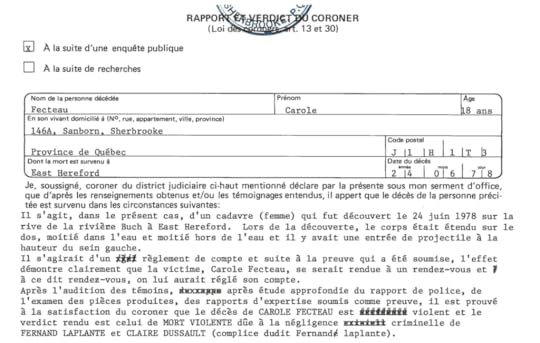

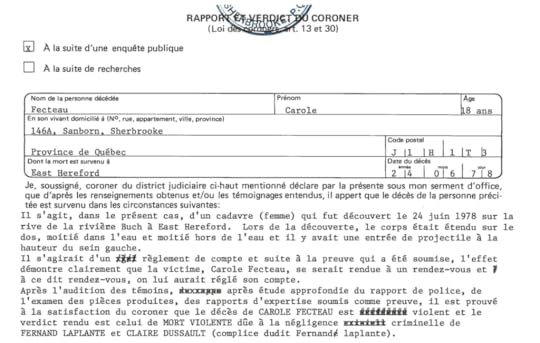

Mario Vallieres

Mario VallieresMario Vallières a également répété le témoignage qu’il avait été reconnu coupable d’une accusation d’incendie criminel “avec le frère du témoin anonyme” (Encore une fois, Jean Charland – il avait été nommé par Vallières pour cet incident seulement six mois plus tôt). Ça devient plus juteux, apparemment Charland avait vécu dans l’appartement qu’ils ont incendié le 4 juin, je suppose qu’il ne voulait plus payer de loyer.

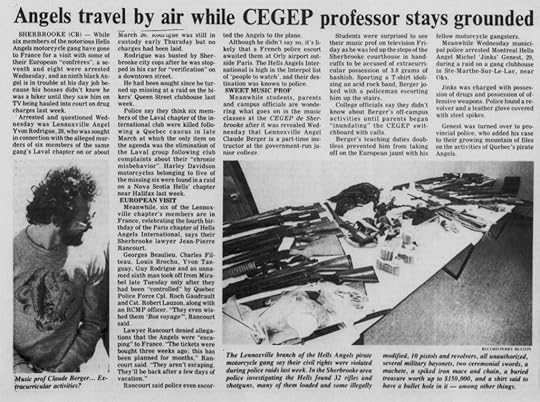

Ce que Mario Vallieres a alors fourni était une fenêtre sur le monde souterrain de la région de Wellington à la fin des années 1970. Il a dit qu’il était actif dans le trafic de drogue à Sherbrooke, vendant à la fois à Jean Charland et à Raymond « Ti Loup » Grimard. Selon Vallières, Grimard vendait de la drogue à des filles comme Carole Fecteau. Il a dit que les principaux endroits où la drogue était poussée au centre-ville de Sherbrooke comprenaient le Moulin Rouge, La Petite Bouffe, la salle de billard de Sinclair, le bar des Marches du Palais, l’hôtel Queen’s et un établissement d’amusement (machines à sous / poker).

Vallières a alors dit avoir vu Jean Charland avec une arme de poing de calibre 32, capable de tirer huit coups. Il ne pouvait pas discerner s’il s’agissait d’une automatique ou d’une semi-automatique. Il a placé le moment où il avait vu l’arme à feu une semaine après l’incendie criminel de la rue Wellington, qui, selon lui, s’était déroulé la nuit des Festivals des Cantons, au début de juin 1978. À la barre, Vallières a refusé de nommer d’autres personnes qui ont vendu drogues dans la région, “Certains d’entre eux ont travaillé pour moi et je ne veux pas les identifier.” Vallières a noté qu’il n’avait jamais fait de transaction de drogue avec Fernand Laplante car il ne faisait pas, à sa connaissance, partie du milieu du crime dans la région de King et Wellington.

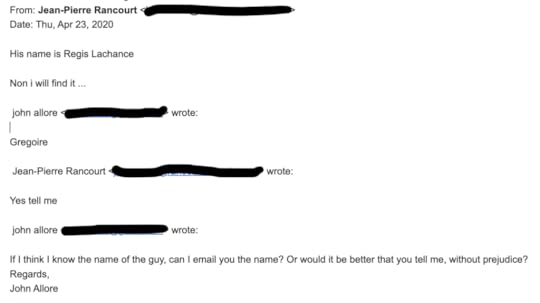

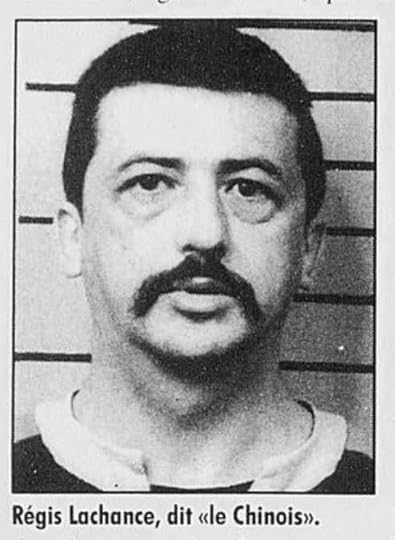

Encore une fois, comme ce fut le cas avec le procès Grimard / Bergeron, la plupart des preuves semblaient pointer vers Jean Charland et son frère Marc, et non Laplante. Jean Charland avait une arme de poing. Bien que les policiers aient trouvé des munitions à l’appartement de Laplante, ils n’ont jamais pu récupérer une arme le liant au meurtre de Fecteau. Laplante ne faisait pas partie du milieu de Wellington, Jean Charland avait vécu à quelques blocs de l’appartement de Fecteau et il était l’un des fournisseurs de médicaments de Fecteau. Jean et Marc Charland étaient deux des dernières personnes vues avec Fecteau dans son appartement de Sanborn. Marc Charland était le petit ami de Fecteau, tandis que Laplante semblait n’avoir aucun motif de la tuer, à moins qu’il ne s’agisse d’un contrat. Enfin, Fernand Laplante ne m’apparaît pas comme un type à la gueule de bavard, bien qu’il y ait eu beaucoup de témoignages de témoins lui mettant des mots dans la bouche (Régis Lachance, et la remarque « Grimard et sa chienne »). Mais Laplante a purgé 40 ans de prison et n’a jamais parlé. Jean Charland par contre…

Daniel « Le Chat » Bussières a témoigné avoir appris la mort de Carole Fecteau par Jean Charland alors que les deux jouaient un partie de snooker au Salle de billard Sinclair:

« Nous avons quitté la salle de billard et nous nous sommes déplacés d’environ 500 pieds jusqu’au Moulin Rouge. J’ai vu Fernand Laplante assis au bar et mon compagnon (Charland) et moi sommes allés… m’asseoir à une table près de la scène.”

“Laplante ‘Surprised’ At Death”, John McCaghey, The Sherbrooke Record, November 29, 1979, page 3

À ce moment-là, Jean Charland se vante à nouveau de Fecteau en leur disant à tous les deux : « elle est bien et elle y sera gelée tout l’hiver ». Bussières a déclaré: «J’ai demandé ce qui s’était passé car je l’avais vue avec Raymond «Ti Loup» Grimard la nuit précédente et sa réponse a été «Attendez et voyez; tu le sauras. »

Quelques jours plus tard, Bussières a rencontré Jean Charland, et cette fois Charland lui a dit de se taire : « Je l’ai fait. parce que vous pouvez avoir des ennuis avec la foule si vous parlez.” Bussières a déclaré à la cour : « La dernière fois que j’ai vu (Fecteau) vivante, c’était lorsqu’elle était avec Ti-Loup Grimard le 20 juin 1978. » Bussières répéta alors la règle populaire du silence dans les crimes qui pourraient impliquer d’autres. Mais Jean Charland n’arrêtait pas de parler, suggérant finalement que Carole Fecteau “avait été tuée par la bande des Grimard à la suite d’une faute dans un deal de drogue : a été violée ».

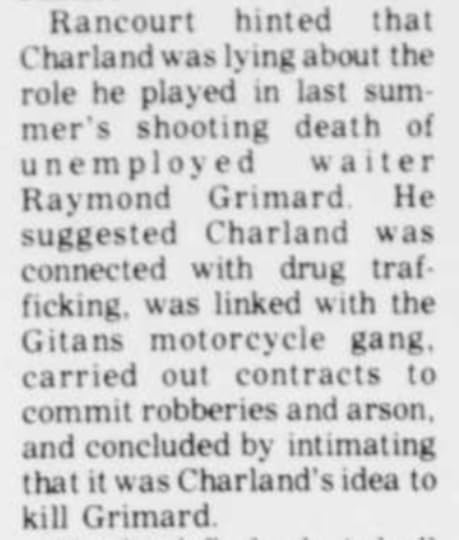

« Justice est bien rendue »Dans sa plaidoirie finale, Jean-Pierre Rancourt a demandé au jury d’acquitter Fernand Laplante au motif qu’il était improbable que son client ait assassiné Carole Fecteau. Il mentionne que le soir du 20 juin 1978, sa colocataire, Hélène Larochelle, a observé Fecteau quittant leur appartement vers 20 h. pour une mystérieuse réunion sur la rue Wellington. Fecteau a ensuite été aperçu par « Le Chat » Bussières dans la Cadillac de « Ti-Loup » Grimard dans la région de Wellington. Rancourt nota que ce même soir Fernand Laplante n’était pas à Sherbrooke, il était à Lennoxville, faisant des travaux de soudure pour un garagiste. Rancourt a déclaré au jury que «personne ne serait assez fou pour dire à un garçon qu’il avait tué sa petite amie», comme Marc Charland a affirmé que Laplante l’avait fait. En fait, la première personne à mentionner le meurtre de Fecteau est le frère de Marc, Jean, lorsqu’il dit à Bussières “elle est bien et qu’elle y sera gelée tout l’hiver”, le lendemain du meurtre du 21 juin. Rancourt a exprimé son opinion que Fecteau était victime d’un trafic de drogue dans lequel elle était impliquée et auquel son client était étranger. Il a conclu en disant que le jury n’avait pas à découvrir qui avait tué Fecteau, mais à décider s’il s’agissait ou non de Laplante.

Le 5 décembre 1979, Fernand Laplante est acquitté du meurtre de Carol Fecteau. Laplante a éclaté en sanglots et a dit : « Justice est bien rendue ». Il retournerait en prison pour une peine de trois ans pour le vol à main armée à Montréal, et sa peine à perpétuité pour les meurtres au premier degré de Raymond Grimard et Manon Bergeron. Bravo en effet.

“Une cause que j’ai encore sur le coeur”Ce n’était peut-être pas le travail du jury de déterminer qui a tué Carole Fecteau, mais c’était le travail de quelqu’un – je vais prendre des risques ici et suggérer hardiment que c’était le travail de la police. Le procureur de la Couronne Claude Melancon a fait semblant de vouloir réessayer Laplante, mais cela a trop échoué. Le meurtre de Fecteau est resté définitivement non résolu.

«Laplante m’avait répété qu’il était innocent dans l’affaire (Grimard et Bergeron). Il n’avait pas fait de telles affirmations pour le meurtre de Carole Fecteau.”

“Me Jean-Pierre Rancourt: Les Confessions d’un Criminaliste”, Bernard Tetrault, Stanke, 2015, Page 60

Pourquoi Fernand Laplante a-t-il épousé Claire Dussault en juillet 1978 ? C’était une question de privilège conjugal, de sorte que Dussault ne pouvait pas témoigner contre son mari. C’était un vieux truc. Laplante avait été un complice criminel avec Gaston « Moustache » Brochu, un Gitan, les deux appartenaient à un équipage spécialisé dans les B&E, ils étaient responsables de centaines de braquages à Sherbrooke et dans les Cantons. Lorsque la justice a rattrapé Brochu, il a tenté d’épouser Christiane Boivin avant toute poursuite pénale.

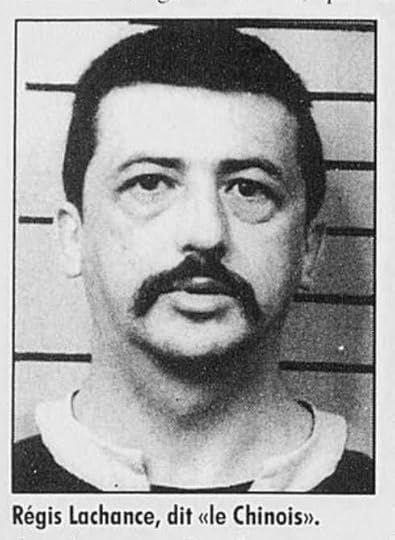

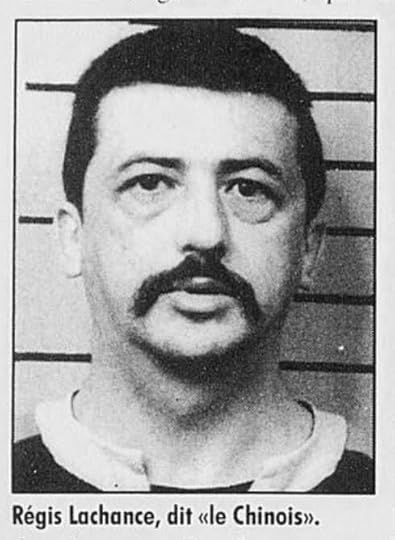

Rappelons maintenant que Fernand Laplante a aussi connu Régis Lachance – comme Brochu, ils ont peut-être aussi été des complices criminels, et ils ont parlé « d’affaires » à l’été 1978 alors que Régis se tenait debout sur le balcon de son appartement de la rue LaRocque. Régis a également épousé l’une de ses femmes à la hâte. Regis a épousé Denise Corbin le 27 octobre 1978, un vendredi – ce qui est curieux, pourquoi ne pas attendre jusqu’à samedi pour que toute la famille puisse faire la fête de l’occasion ? – mais non, Régis s’est marié le vendredi 27 octobre 1978, exactement une semaine avant la disparition de Theresa Allore, et deux semaines avant l’incendie de l’Aloha Motel. Donc, cette astuce de mariage semble avoir été transmise con à con.

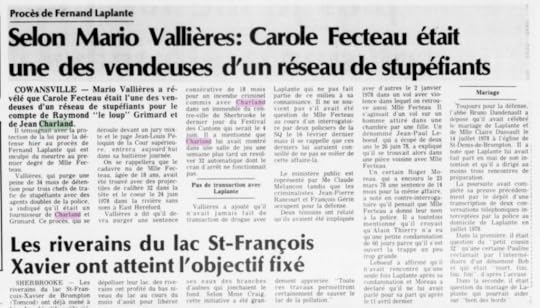

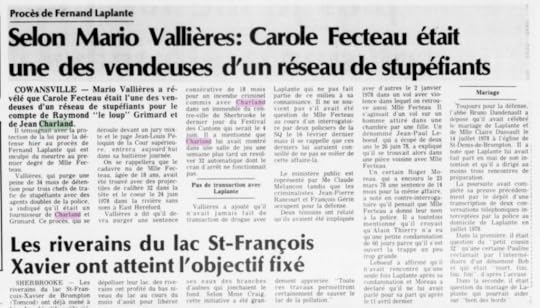

À noter que lorsque le coroner Jean-Pierre Rivard a rendu son verdict le 16 octobre 1978 tenant Fernand Laplante criminellement responsable de la mort violente de Carole Fecteau, il a nommé Claire Dussault également complice du meurtre :

En fait, Dussault devait également être jugé pour le meurtre de Fecteau, mais ce processus a échoué. De plus, Dussault a été appelé à témoigner procès pour meurtre de Fecteau, mais elle était absente.

À l’été 1978, la Sûreté du Québec a mis sur écoute légale le téléphone de Laplante dans son appartement du Belvédère. Au procès, la poursuite avait déposé en preuve une transcription de deux conversations téléphoniques interceptées par les policiers au domicile de Laplante. Dans le premier, Laplante a parlé de son récent mariage et de la façon dont cela pourrait aider « à bien des égards ». Dans le second, la conversation téléphonique faisait référence à quelqu’un appelé “petit cousin 32” qui était “mort”. fini, fini, fini ».

“Petit Cousin” est un terme familier, il peut signifier beaucoup de choses. Mais il faut mentionner que Carole Fecteau était la petite cousine de Denise Côté, l’épouse de Gérald Lachance. Et Gérald était le frère de Régis Lachance.

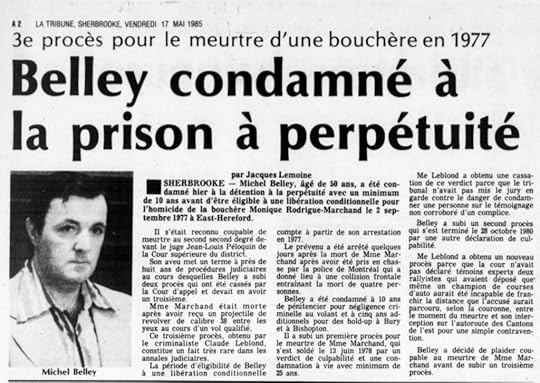

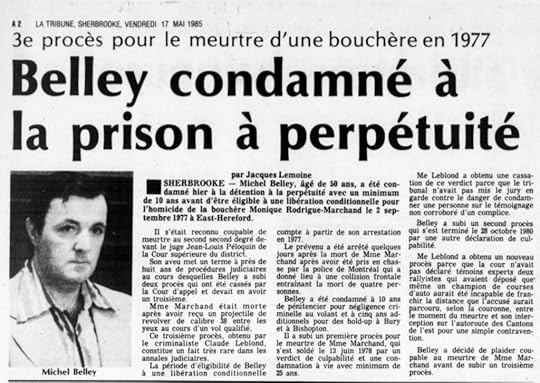

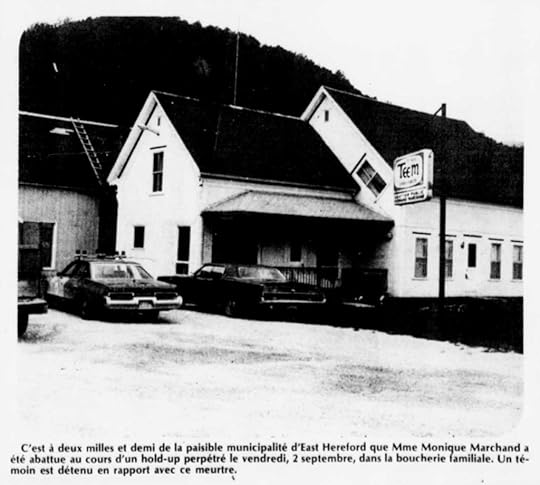

Le double événement d’East HerefordLe vendredi après-midi 2 septembre 1977, au début de la fin de semaine de la fête du Travail, quelqu’un a tiré sur Monique Marchand, 37 ans, commis d’une boucherie et mère de trois enfants, alors qu’elle travaillait au comptoir de son magasin à East Hereford. Le bandit solitaire a cambriolé l’abattoir Fernand Marchand, ne saisissant qu’une poignée d’argent dans la caisse, et s’est enfui dans une Camaro rouge et noire en attente avec des plaques d’immatriculation américaines, retrouvée plus tard abandonnée sur une route secondaire. Le marché était situé à 2 1/2 milles au sud d’East Hereford, le long de la route menant au passage frontalier de Beecher Falls, dans le Vermont. Madame Marchand était seule dans la devanture lorsque l’incident s’est produit, mais son beau-père, Johnny Marchand, était dans l’arrière-boutique. Il a dit avoir entendu un coup de feu et lorsqu’il s’est approché du front, il a vu un homme debout près de la caisse, l’arme pointée sur sa belle-fille. Madame Marchand était sur le point de lancer une viande intelligente sur l’homme, à quel point il lui a tiré une balle dans la tête.

Ce qui est curieux à propos de ce vol de magasin familial à Nowheresville, Québec, c’est que l’enquête était dirigée par nul autre que Roch Gaudreault de la SQ de Sherbrooke, à près de 60 kilomètres. On se demande pourquoi quelqu’un comme Jacques Filion n’a pas pris en charge le détachement beaucoup plus proche de Coaticook. La première action de Gaudreault a été de mettre en place des barrages routiers, ce qui vous dit que presque immédiatement, la police n’a pas pensé qu’elle cherchait un local.

Lundi, la police avait arrêté Michel Belley, et lorsque l’histoire a éclaté dans la Montréal Gazette selon laquelle le criminel notoire – Belley avait commis une série de vols de Québec à Toronto en passant par Kansas City – avait été appréhendé, la Sûreté du Québec de Sherbrooke l’a appelé, « pur fantasme, Michel Belley n’est absolument pas détenu à cette fin. Ces journalistes nuisent beaucoup plus à l’enquête qu’ils ne peuvent l’aider en faisant de telles déclarations.”

Néanmoins, à la fin de la fin de semaine fériée, 72 heures époustouflantes après la fusillade de Marchant, le caporal Roch Gaudreault et le constable Noël Bolduc, du Bureau des enquêtes criminelles de la SQ, ainsi que le coroner Jean-Pierre Rivard, « font savoir qu’ils étaient certains d’avoir résolu le meurtre d’East Hereford », malgré le fait que la seule preuve contre Belley était qu’il avait autrefois vécu à Sherbrooke.

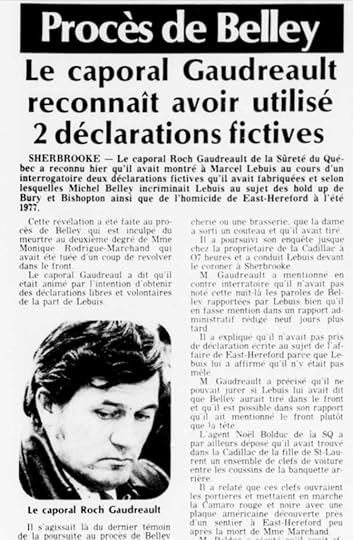

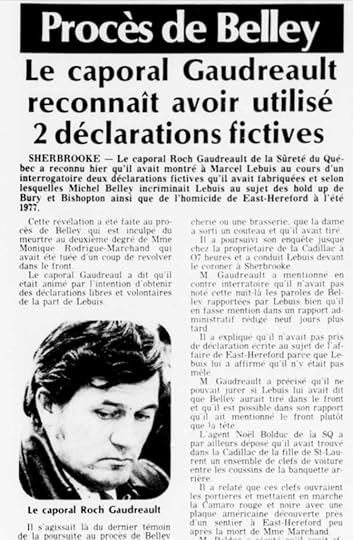

Belley a été acquitté deux fois pour le meurtre. La première occasion due au “témoignage non corroboré d’un complice”. En cour, il a été révélé que le caporal Roch Gaudreault avait fabriqué des preuves afin d’incriminer Belley. Plus précisément, Gaudreault a écrit deux déclarations fictives puis a falsifié la signature de Michel Belley sur les documents. Les documents auraient impliqué le complice dans le meurtre, dans le but d’amener ensuite ce complice à, à son tour, blâmer Belley pour le meurtre. L’associé de Gaudreault, Noel Bolduc a préparé les documents, puis Gaudreault les a signés.

On a donc là une fabrication de preuves, et une collusion policière d’une manière identique à ce que l’agent de la SQ Réal Châteauneuf a décrit dans le procès Laplante (“C’est une des ruses habituellement utilisées.” ), et utilisée pour amener Jean Charland à incriminer Fernand Laplante . Ce n’était donc pas une indiscrétion ponctuelle, c’était une pratique systémique de la Sûreté du Québec. La police utilise ce que Bob Beullac a appelé des « raccourcis » ; mais ce n’est pas un jeu, des vies étaient en jeu lorsque la police a joué vite et librement avec la loi.

À la deuxième occasion, un expert a déterminé qu’il était physiquement impossible pour Belley d’avoir conduit d’East Hereford à l’endroit où il a ensuite été repéré ce soir-là à Montréal dans le temps imparti, «même un champion de course automobile aurait été incapable de surmonter la distance. “, il a dit. En 1985, Belley a simplement abandonné et a plaidé coupable, j’imagine avoir choisi de purger sa peine plutôt que de subir d’autres absurdités du processus judiciaire québécois.

“Elle s’est bien débrouillée avant d’être tuée”

“Elle s’est bien débrouillée avant d’être tuée”Pourquoi quelqu’un va-t-il à East Hereford ? Pour la même raison que vous prenez un bateau sur les eaux internationales du lac Memphrémagog, c’est une ville frontalière, c’est un port ou une entrée pour les voitures et les drogues et les armes à feu, ou les drogues et les armes à feu dans les voitures, si vous préférez – smuggling. Celui qui a braqué le boucher en 1977 – et ce n’était pas Michel Belley – avait plus en tête que la main vide de sens l d’argent qu’ils ont saisi de la caisse enregistreuse. Et ce Camero abandonné ? Eh bien, l’agresseur n’est pas simplement sorti d’East Hereford, il y avait plus d’une personne impliquée et il y avait deux voitures.

Fernand Marchand Abattoir – East Hereford

Fernand Marchand Abattoir – East HerefordNous avons mentionné que même l’avocat Rancourt soupçonnait Laplante d’avoir participé au meurtre de Fecteau, et que Laplante était de Coaticook, à seulement 25 kilomètres à l’ouest d’East Hereford à vol d’oiseau. Or, pendant un certain temps, Fernand Laplante avait travaillé comme ouvrier agricole sur le terrain où le corps de Carole Fecteau a été découvert, Buck Creek. Cela n’est jamais sorti au procès, mais on croit que la raison pour laquelle la Couronne a voulu appeler Claire Dussault à la barre était de témoigner que le soir du meurtre de Fecteau, Fernand Laplante ne faisait pas de soudure dans un garage de Lennoxville, mais était en fait dans la région de Coaticook famille en visite.

Cela rend Fernand Laplante probable comme l’un des assaillants de Fecteau, mais pas tous. Comme pour la fusillade de Monique Marchand et les meurtres de Grimard et Bergeron – où Jean Pierre Rancourt a suggéré qu’il y en avait jusqu’à quatre – il y avait plus d’une personne impliquée dans le meurtre de Carole Fecteau.

Que penser du témoignage de Daniel “Le Chat” Bussières selon lequel Jean Charland a déclaré que Fecteau “avait bien essayé avant d’être tuée” ? Pour un viol collectif, il faut un gang. Et tant pis pour l'”expert” médico-légal, qui a témoigné que Fecteau n’avait pas été sexuellement active avant sa mort. Comme Jean-Claude Bernheim l’avait dit à plusieurs reprises, des « experts » mentent sur ces choses pour étayer un récit policier. Ils mentent ou ils n’ont pas compris (ils ne comprennent pas) tout l’arsenal d’opportunités à la disposition d’un délinquant par rapport aux femmes lorsqu’il envisage la nature du viol.

Donc, oui, quelqu’un dans ce parti a peut-être voulu que Fecteau soit tué parce qu’elle avait une grande gueule, ou qu’elle a foiré un deal de drogue, mais quelqu’un d’autre – ou d’autres personnes – dans ce parti voulait autre chose, quelque chose en plus de la faire tuer . Parce que s’il s’agit d’un simple contrat de meurtre, vous ne déshabillez pas le corps. Si ce n’est qu’un meurtre pour compte, tu la laisserais comme ils ont laissé Manon Bergeron, habillée. Vous ne jetez pas de preuves le long d’une route de gravier, comme les vêtements et un portefeuille, comme ils l’ont fait avec Theresa Allore. Quelqu’un – ou d’autres – dans ce groupe n’était pas seulement un tueur à gages. Ils étaient aussi un meurtrier sexuel.

May 27, 2022

Muzzled Justice

There’s a photo of Surete du Quebec agent, Jacques Filion staring into a garbage bag of clothing at my sister’s dump site the morning she was found, April 13, 1979. Roch Gaudreault is with him, pretending to gaze into the plastic bag. Wish You Were Here has the agent misidentified as Jacques Lessard, but it’s Filion, the guy from Fecteau’s case. Filion was the agent who recovered Carole’s clothing.

Roch Gaudreault et Jacques Filion

Roch Gaudreault et Jacques FilionThere’s a second photo from that morning – Good Friday, April 13, 1979 – the two agents standing next to a tree where Theresa’s body lay, pretending to have a conversation. The photos are staged; the detectives aren’t really doing anything, they’re not really investigating.

Jacques Filion et Roch Gaudreault

Jacques Filion et Roch GaudreaultIt was never determined who’s clothing was in that bag. It wasn’t Theresa’s. Was it Fecteau’s? Not the clothes she was wearing, Filion found those. But what if it was clothing left with her young boyfriend, Marc Charland? What if, around the time that agent Real Chateauneuf found that bullet-riddled birch log under the basement stairs at the Charland’s, around January, 1979, his big brother, Jean noticed the clothing in Marc’s room and told his little brother, “Hey, you gotta get rid of that stuff, you’re under 18, you don’t want the cops thinking you had anything to do with her shooting.”

So Jean Charland gathered all Fecteau’s stuff, put in a garbage bag and ditched it, but just for a laugh, just to screw around with police, he tossed it at the site where he knew later that spring when the snow melted, they were going to find another dead girl. Some joke, right? Because Jean Charland knew the police weren’t going to mess with him, a made man. So when Jacques Filion looked into that garbage bag, Good Friday, April 13, 1979, and he saw that clothing, did he know at that moment, on the eve of Fernand Laplante’s trial for two murders he did not commit, that the Surete du Quebec was missing the big picture? That they had a serious problem on their hands with sexual murder?

People will hold us to blame Carole Fecteau

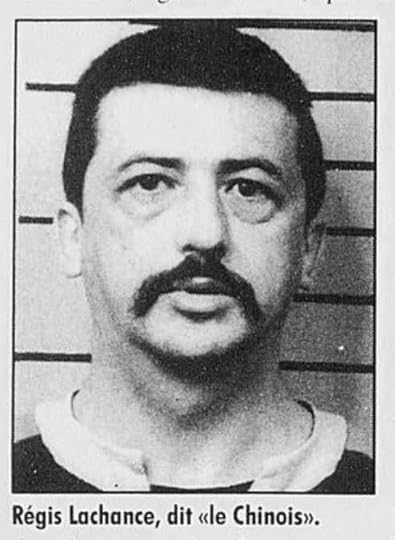

Carole FecteauThe first to be murdered, Carole Fecteau would be the last to have her day in court. Once again, police decided to put Fernand Laplante on trial, and no one else. Once again, Laplante was assisted by defense attorney, Jean-Pierre Rancourt, who won a motion to move the process to Cowansville, about 100 kilometers west of Sherbrooke, due to excessive publicity during Laplante’s first trial. The Crown was represented again by Claude Melancon, and both attorneys agreed to include several admissions from the Grimard and Bergeron murder trials in an effort to avoid redundancy and speed the judicial process – this was going to be a swift hatchet-job.

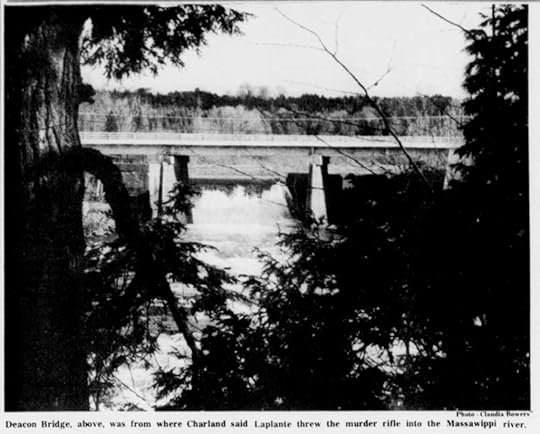

Fecteau’s affair opened on Monday, November 19, 1979. Jacques Mongeau testified how he and a friend had gone fishing in a stream near East Hereford on June 24, 1978, and discovered the nude body of a young woman who was “white, not breathing and appeared to have worms coming out of her skin.” A provincial public works employee then took the stand to say on June 26 he found a wallet, “at the side of a gravel road”, running toward East Hereford. Before taking the wallet to police, the man blazed a tree with an axe to mark the location where the wallet was found.

Buck Creek in East Hereford, where Carole Fecteau was found

Buck Creek in East Hereford, where Carole Fecteau was foundA forensic expert told the court that Fecteau died from two bullets shot from a handgun, the first having entered at the nape of the neck at a distance of about six feet, while the second entered her thorax, penetrating the left lung and heart, which could have been fired from point blank range. There were no traces of alcohol in Fecteau’s body, and for some reason, Fecteau was not tested for drugs. This expert stated Fecteau had not been sexually active 24 hours prior to her death.

Jacques Filion

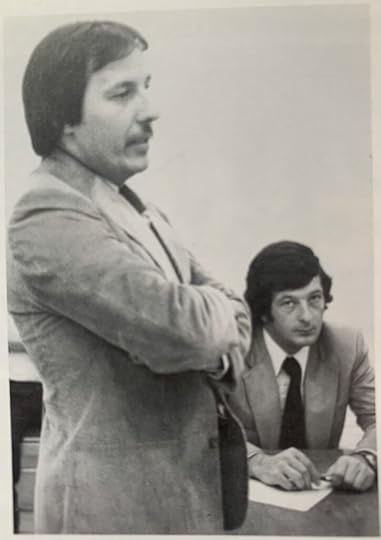

Jacques FilionSQ photographer Guimond Desbiens testified how he took photographs at the scene near East Hereford, and said he was struck by the tattoos on her body, but could not recall noticing any names. The SQ’s Michel Poulin said he took aerial photographs of the scene in January and October of 1979, as well as some of the Wellington Street area of Sherbrooke on November 15.

It was SQ agent Jacques Fillion who eventually ended up with the wallet, and he testified that her clothing; jeans, underwear and sweater, were recovered the same day as her torn poncho at two different points on the same road. At this point, Rancourt asked if Fillion was aware that Marc and Jean Charland lived in the Lennoxville area at the time of the crime, Fillion confirmed that he was aware.

Like any other candidateThe next day, The Sherbrooke Record reported this curiosity:

“The majority of yesterday’s testimony in the case of Fernand Laplante, charged with first degree murder in the death of Carole Fecteau at East Hereford on June 20, 1978, was devoted to the testimony and cross examination of a young male. The press notably only represented by The Record were forbidden to mention his name, address, age, occupation, as well as the Christian name of his brother. Justice Jean Louis Peloquin also imposed other restrictions concerning his testimony.”

“Judge sets press rules”, John McCaghey, Sherbrooke Record, November 22, 1979, page 3

The absence of the Townships major French newspaper, La Tribune was so noticeable, it was called out by the Townships sister, English publication The Record. In fact, La Tribune was missing for the first six days of the trial. The “young male” the courts were trying to “protect” was rather obviously Carole Fecteau’s boyfriend, Marc Charland, and the Christian name of his brother was Jean. However, having not been present, La Tribune never heard the court’s publication ban, and so proceed to expose the name “Charland” all through their subsequent reporting:

Under the court’s protection, Marc Charland’s testimony was essentially a mini-version of Jean Charland’s story in the Grimard and Bergeron trial: he blamed Fernand Laplante for the murder of Carole Fecteau. Marc Charland claimed that Laplante once told him Fecteau “was a bitch and had to die”. Then on June 20, 1978, the night of Fecteau’s disappearance, according to Charland, Laplante again confided that Fecteau “was dead, that her case was settled and that he had put her in a creek.” Apparently Fernand Laplante couldn’t stop talking about Fecteau because on June 21, 34-year-old Laplante again confided to this boy under the age of 18 that Fecteau “had bullets in her head and heart because she sent two guys to jail.” Under cross-examination, Marc Charland toned down his statement and said he may have misinterpreted Laplante’s remarks. Marc Charland’s testimony was the chief evidence used by the Crown to prosecute Laplante.

Helen Larochelle

Helen LarochelleThe Crown brought back Fecteau’s roommate, Helen Larochelle, and under cross examination, Jean Pierre Rancourt got her to admit that shortly before Carole’s disappearance on or around June 20, 1978, their apartment was visited by “two brothers who must remain anonymous”, but who we know now were Marc and Jean Charland. Fecteau last talked on the phone twice to Johanne Tanguay, before departing the apartment around 8:00 p.m., and heading for Wellington Street.

Mario Vallieres also repeated testimony that he had been convicted of an arson charge “with the brother of the anonymous witness” (Once again, Jean Charland – he had been named by Vallieres for this incident only six months earlier). It gets juicier, apparently Charland had lived in the apartment they burned down on in June 4, I guess he no longer wanted to pay rent.

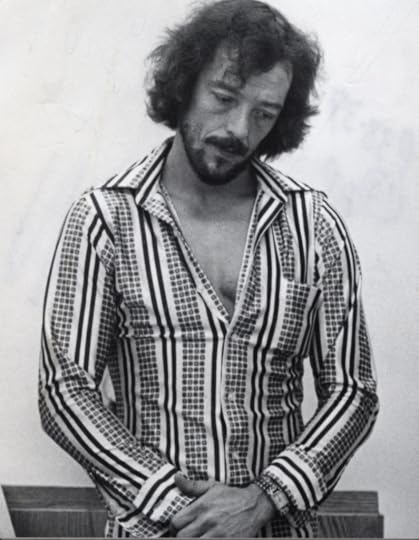

Mario Vallieres

Mario VallieresWhat Mario Vallieres then provided was a window into the underworld of the Wellington area in the late 1970s. He said that he was active in the drug trade in Sherbrooke, selling to both Jean Charland and Raymond “Ti Loup” Grimard. According to Vallieres, Grimard sold drugs to girls like Carole Fecteau. He said the main areas where drugs were pushed in downtown Sherbrooke included the Moulin Rouge. La Petit Bouffe. Sinclair’s Pool Room, the bar at Les Marches du Palais, the Queen’s Hotel and an amusement establishment (slots, pinball).

Vallieres then said he had seen Jean Charland with a 32-calibre handgun, capable of firing eight shots. He could not discern whether it was an automatic or a semi automatic. He placed the time he had seen the gun as being a week after the arson on Wellington St., which he said was set on the night of Festivals des Cantons, in early June 1978. On the stand, Vallieres refused to name others who sold drugs in the area, “Some of them worked for me and I don’t want to identify them.” Vallieres noted that he never made a drug transaction with Fernand Laplante as he was not, to his knowledge, part of the crime milieu in the King and Wellington area.

Again, as was the case with the Grimard / Bergeron trial, most of the evidence, appeared to be pointing to Jean Charland and his brother Marc, not Laplante. Jean Charland had a handgun. Though police found ammunition at Laplante’s apartment, they were never able to recover a weapon linking him to Fecteau’s murder. Laplante was not part of the Wellington milieu, Jean Charland had lived within blocks of Fecteau’s apartment, and he was one of Fecteau’s drug suppliers. Jean and Marc Charland were two of the last persons seen with Fecteau at her apartment on Sanborn. Marc Charland was Fecteau’s boyfriend, whereas Laplante appeared to have no motive for killing her, unless it was a contract hit. Finally, Fernand Laplante does not strike me as a guy with a blabber-mouth, though there was a lot of testimony of witnesses putting words in his mouth (Regis Lachance, and the “Grimard and his bitch” remark). But Laplante served 40 years in prison and never talked. Jean Charland on the other hand…

Daniel “Le Chat” Bussières testified that he learned of Carole Fecteau’s death from Jean Charland while the two were playing a game of snooker at the Sinclair Pool Hall:

“We left the poolroom and moved about 500 feet to the Moulin Rouge. I saw Fernand Laplante sitting at the bar and my companion (Charland) and I went to… sit at a table near the stage.”

“Laplante ‘Surprised’ At Death”, John McCaghey, The Sherbrooke Record, November 29, 1979, page 3

At this point, Jean Charland bragged about Fecteau again, telling both of them, “she’s well off and she’ll be frozen there all winter.” Bussières said, “I asked what happened as I had seen her with Raymond “Ti Loup” Grimard the night prior and his answer was “Wait and see; you’ll find out.””

Several days later, Bussières met up with Jean Charland, and this time Charland told him to shut up, “I did. because you can get into trouble with the mob if you talk.” Bussières told the court, “The last time I saw (Fecteau) alive was when she was with Ti-Loup Grimard on June 20, 1978.” Bussières then repeated the mob rule on silence in crimes which might implicate others. But Jean Charland couldn’t stop talking, finally suggesting that Carole Fecteau had been slain by the Grimard gang as a result of a foul up in a drug deal: “He told me she had a good go before she was killed and l presume she was raped.”

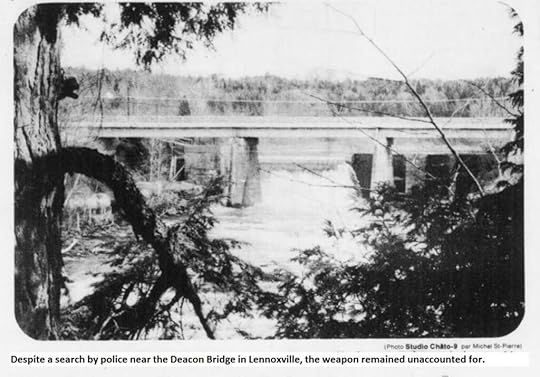

“Justice is well done”In his closing arguments, Jean-Pierre Rancourt asked the jury to acquit Fernand Laplante on the grounds that it was improbable that his client murdered Carole Fecteau. He mentioned that on the evening of June 20, 1978, her roommate, Hélène Larochelle observed Fecteau leaving their apartment around 8:00 p.m. for a mysterious meeting on Wellington Street. Fecteau was later seen by “Le Chat” Bussières in the Cadillac of “Ti-Loup” Grimard in the Wellington area. Rancourt noted that that same evening Fernand Laplante was not in Sherbrooke, he was in Lennoxville, doing some welding work for a garage owner. Rancourt told the jury that “no one would be crazy enough to tell a boy that he had killed his girlfriend”, as Marc Charland claimed Laplante had done. In fact the first person to mention Fecteau’s murder was Marc’s brother, Jean, when he told Bussières “she’s well off and she’ll be frozen there all winter”, the day after the murder on June 21. Rancourt expressed his opinion that Fecteau was the victim of a drug deal in which she was involved, and to which his client was a stranger. He concluded by saying that the jury did not have to find out who killed Fecteau, but to decide whether or not it was Laplante.

On December 5, 1979, Fernand Laplante was acquitted of the murder of Carol Fecteau. Laplante burst into tears and said, “Justice is well done”. He would return to prison for a three-year sentence of the armed robbery in Montreal, and his life sentence for the first-degree murders of Raymond Grimard and Manon Bergeron. Well done indeed.

“Une cause que j’ai encore sur le coeur”It may not have been the jury’s job to determine who killed Carole Fecteau, but it was someone’s – I’ll go out on a limb here and boldly suggest it was the police’s job. Crown attorney Claude Melancon made a show of wanting to re-try Laplante, but that too fizzled. Fecteau’s murder was left permanently unresolved.

“Laplante had repeated to me that he was innocent in (the Grimard and Bergeron) case. He had not made such assertions for the murder of Carole Fecteau.”

“Me Jean-Pierre Rancourt: Les Confessions d’un Criminaliste”, Bernard Tetrault, Stanke, 2015, Page 60

Why did Fernand Laplante marry Claire Dussault in July 1978? It was a question of spousal privilege, so that Dussault could not testify against her husband. This was an old trick. Laplante had been a criminal partner with Gaston “Moustache” Brochu, a Gitan, the two belonged to a crew that specialized in B&Es, they were responsible for hundreds of robberies in Sherbrooke and the Townships. When the law caught up with Brochu, he tried to marry Christiane Boivin before any criminal processes.

Now recall that Fernand Laplante also knew Regis Lachance – like Brochu, they also may have been criminal partners, and they spoke about “business” in the summer of 1978 while Regis was standing on the balcony of his apartment on Rue LaRocque. Regis also married one of his wife’s in a hasty fashion. Regis wed Denise Corbin on October 27, 1978, a Friday – which is curious, why not wait until Saturday when the whole family can make a party of the occasion? – but no, Regis was married on Friday, October 27, 1978, exactly one week before Theresa Allore’s disappearance, and two weeks prior to the Aloha Motel fire. So this marriage trick, appears to have been something handed down from con to con.

Note that when Coroner Jean-Pierre Rivard issued his verdict on October 16, 1978 holding Fernand Laplante criminally responsible for the violent death of Carole Fecteau, he named Claire Dussault equally complicit in the murder:

In fact, Dussault was set to also stand trial for Fecteau’s murder, but that process fizzled. As well, Dussault was called to testify at Fecteau’s murder trial, but she was a no-show.

In the summer of 1978, the Surete du Quebec placed a legal wiretap on Laplante’s phone in his apartment on Belvedere. At the trial, the prosecution had filed into evidence a transcript of two intercepted telephone conversations by the police at Laplante’s home. In the first, Laplante talked about his recent marriage, and about how it could help,“on many sides”. In the second, the phone conversation referenced someone called “little cousin 32″ who was “dead. finished, finished, finished”.

“Little Cousin” is a familiar term, it can mean many things. But it’s worth mentioning that Carole Fecteau was the little cousin of Denise Côté, the wife of Gerald Lachance. And Gerald was the brother to Regis Lachance.

The East Hereford Double EventOn Friday afternoon, September 2, 1977, the start of Labor Day weekend, someone shot 37-year-old Monique Marchand, a butcher store clerk and mother of three, while she was working the counter of her store in East Hereford. The lone bandit robbed the Fernand Marchand Abattoir, grabbing only a handful of cash from the till, and got away in a waiting red and black Camaro with American license plates, later found abandoned on a secondary road. The market was located 2 1/2 miles south of East Hereford, along the road to the Beecher Falls, Vermont border crossing. Madame Marchand was alone in the storefront when the incident occurred, but her father in-law, Johnny Marchand, was in the back room. He said he heard a shot and when he approached the front, saw a man standing near the cash, with the gun pointed at his daughter-in-law. Madame Marchand was about to launch a meat clever at the man, at which point he shot her in the head.

What’s curious about this mom-and-pop store robbery in nowheresville, QC, is that the investigation was headed up by none other than Roch Gaudreault from the Sherbrooke SQ, nearly 60 kilometers away. One wonders why someone like Jacques Filion didn’t take charge from the much closer Coaticook detachment. Gaudreault’s first action was to set up road blocks, which tells you that almost immediately, the police didn’t think they were looking for a local.

By Monday, police had arrested Michel Belley, and when the story broke in the Montreal Gazette that the notorious criminal – Belley had committed a string of thefts from Quebec to Toronto to Kansas City – had been apprehended, Sherbrooke’s Sûreté du Québec called it, “pure fantasy, Michel Belley is absolutely not detained for this purpose. These journalists harm the investigation much more than they can help it by making such declarations.”

Nevertheless, at the conclusion of the holiday weekend, a breathtaking 72-hours after the Marchant shooting, Corporal Roch Gaudreault and Constable Noël Bolduc, from the SQ’s Criminal Investigations Bureau, along with Coroner Jean-Pierre Rivard, “let it be known that they were certain of having solved the East Hereford murder”, despite the fact that the only evidence against Belley was that he had once lived in Sherbrooke.

Belley was acquitted twice for the murder. The first occasion due to the “uncorroborated testimony of an accomplice.” In court is was revealed that Corporal Roch Gaudreault fabricated evidence in order to incriminate Belley. Specifically, Gaudreault wrote two ficticious statements and then forged Michel Belley’s signature on the documents. The documents would have implicated the accomplice in the murder, with the goal of then getting this accomplice to, in turn, blame Belley for the murder. Gaudreault’s partner, Noel Bolduc prepared the documents and then Gaudreault signed them.

So here we have the fabrication of evidence, and police collusion in a manner identical to what SQ agent Real Chateauneuf described in the Laplante trial (“It’s one of the tricks usually used.” ), and used to get Jean Charland to incriminate Fernand Laplante. So this was not a one-time indiscretion, it was a systemic practice of the Surete du Quebec. Police using what Bob Beullac called “short cuts”; but it’s no game, lives were at stake when police played fast and loose with the law.

On the second occasion, an expert determined it was physically impossible for Belley to have driven from East Hereford to where he was later spotted that evening in Montreal in the time allotted, “even a car racing champion would have been unable to overcome the distance.”, he said. By 1985, Belley simply gave up and pleaded guilty, I imagine choosing to serve his time rather than endure any more nonsense from the Quebec judicial process.

“She had a good go before she was killed”

“She had a good go before she was killed”Why does anyone go to East Hereford? For the same reason you take a boat across the international waters of Lake Memphremagog, it’s a border town, it’s a port-or-entry for cars and drugs and guns, or drugs and guns in cars, if you prefer – smuggling. Whoever robbed the butcher in 1977 – and it wasn’t Michel Belley – had more on their mind than the meaningless handful of cash they grabbed from the register. And that abandoned Camero? Well, the assailant didn’t just walk out of East Hereford, there was more than one person involved, and there were two cars.

Fernand Marchand Abattoir – East Hereford

Fernand Marchand Abattoir – East HerefordWe’ve mentioned that even attorney Rancourt suspected Laplante had a hand in Fecteau’s murder, and that Laplante was from Coaticook, just 25 kilometers west of East Hereford as the crow flies. Now for a time, Fernand Laplante had worked as a farm laborer on the land where Carole Fecteau’s body was discovered, Buck Creek. That never came out at trial, but it is believed that the reason the Crown wanted to call Claire Dussault to the stand was to testify that the evening of Fecteau’s murder Fernand Laplante was not welding at a Lennoxville garage, but was actually in the Coaticook area visiting family.

That makes Fernand Laplante probable as one of Fecteau’s assailants, but not all of them. As with Monique Marchand’s shooting, and the murders of Grimard and Bergeron – where Jean Pierre Rancourt suggested there were as many as four – there was more than one person involved in Carole Fecteau’s murder.

For what to make of Daniel “Le Chat” Bussieres testimony that Jean Charland said Fecteau “had a good go before she was killed”? For a gang rape you need a gang. And never mind the forensic “expert”, who testified that Fecteau had not been sexually active prior to her death. As Jean-Claude Bernheim had stated many times, “experts” lie about these things to support a police narrative. They lie, or they did not (they do not) understand the full arsenal of opportunities available to an offender over women when contemplating the nature of rape.

So, yes, someone in that party may have wanted Fecteau killed because she had a big mouth, or she screwed up a drug deal, but someone else – or other persons – in that party wanted something else, something in addition to having her killed. Because if it’s a simple contract killing, you don’t strip the body naked. If it’s just a murder-for-hire, you’d leave her like they left Manon Bergeron, clothed. You don’t toss evidence along a gravel road, like the clothing and a wallet, like they did with Theresa Allore. Someone – or others – in that group wasn’t just a contract killer. They were also a sexual murderer.

May 20, 2022

Jean Charland – Le Fils Prodigue

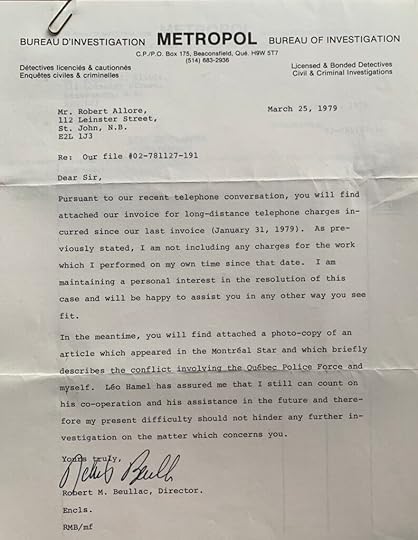

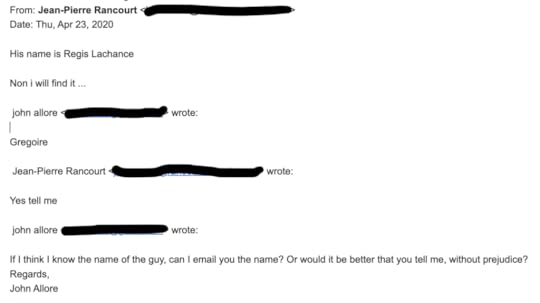

“Cher Monsieur Allore,

… vous trouverez ci-joint une photocopie d’un article paru dans le Montreal Star et qui décrit brièvement le conflit entre la Sûreté du Québec et moi-même. Leo Hamel m’a assuré que je pourrai toujours compter sur sa coopération et son aide à l’avenir et que ma difficulté actuelle ne devrait donc pas empêcher toute enquête plus approfondie sur l’affaire qui vous concerne.

Votre sincèrement.

Robert M. Beullac, directeur, Metropol Bureau of Investigation »

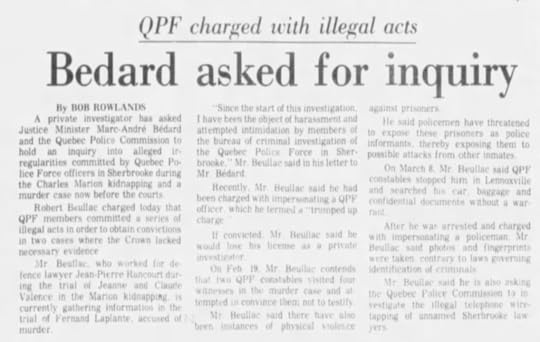

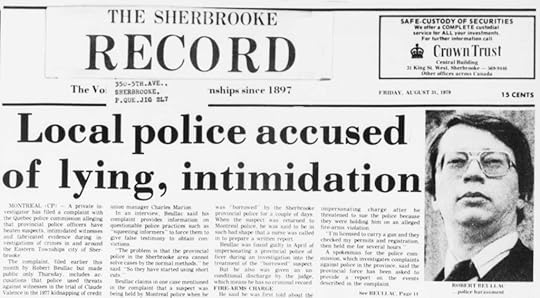

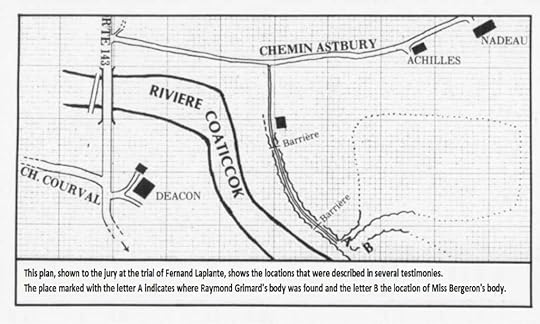

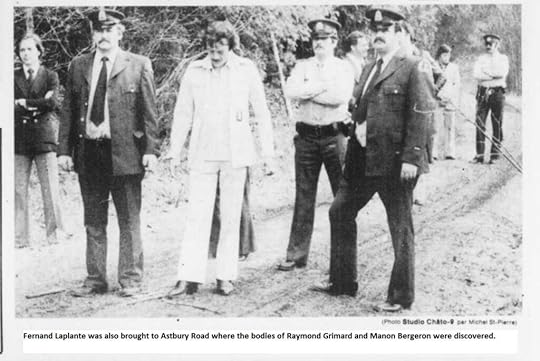

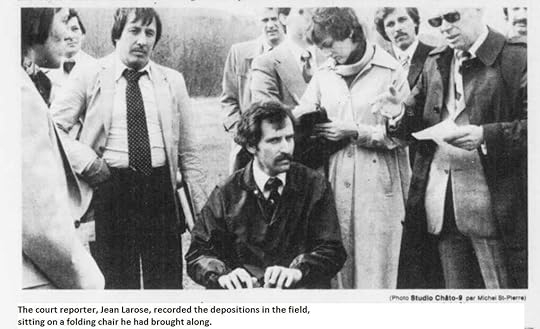

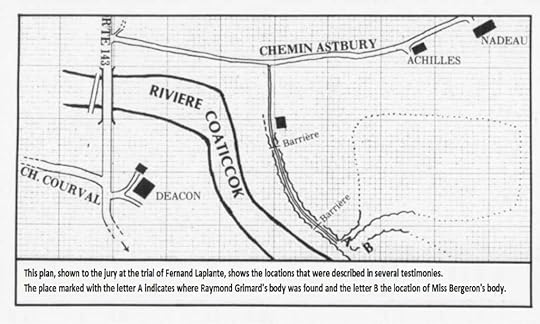

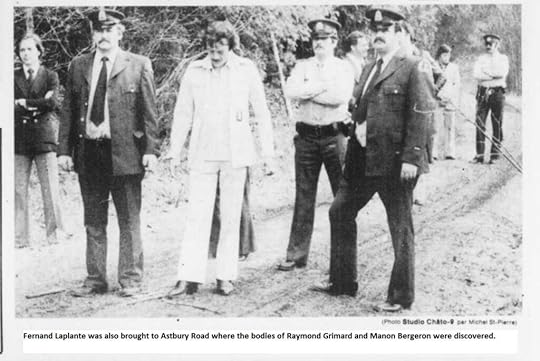

À l’issue du procès de Fernand Laplante, la Sûreté du Québec a fait arrêter l’enquêteur privé Robert Beullac pour s’être fait passer pour un policier auprès des résidents du chemin Astbury lors de l’expérience où il a prouvé qu’une arme à feu n’a pas été tirée à l’endroit la nuit de les meurtres de Grimard et Bergeron.

Les accusations étaient des représailles contre Beullac pour avoir déposé une plainte auprès de la Commission de police du Québec alléguant que «des policiers provinciaux avaient battu des suspects, intimidé des témoins et fabriqué des preuves lors d’enquêtes sur des crimes dans et autour de la ville de Sherbrooke, dans les Cantons-de-l’Est». Beullac avait documenté plusieurs passages à tabac par la SQ contre des résidents des Cantons. Plus précisément, il a cité les enquêteurs de la SQ pour avoir sauvagement battu Fernand Laplante à plusieurs reprises lors de son arrestation initiale entre le 3 et le 5 août 1978. Il a accusé la Sûreté du Québec de s’être livrée à des «actes de brutalité, d’intimidation envers des témoins à décharge» en précisant qu’un enquêteur avait tordu les seins de la femme de Laplante, Claire Dussault. Beullac a en outre allégué que les enquêteurs avaient eu une conversation inappropriée et décontractée avec le jury lors du procès de Laplante. Robert Beullac n’était que l’un des nombreux Québécois à demander justice au ministre Marc-André Bédard en 1979. Le père de Diane Dery (assassinée avec Mario Corbeil) a adressé une pétition à Bédard au sujet de l’enquête bâclée de sa fille. Avant la clôture de cette année-là, Bedard a dû ordonner une enquête sur la fusillade par la police de la SQ de dans la réserve de Kahnawake au sud de Montréal.

« Le problème, c’est que la police provinciale de la région de Sherbrooke n’arrive pas à résoudre les cas par les méthodes normales… alors ils ont commencé à utiliser des raccourcis »

“Local police accused of lying, intimidation”, Sherbrooke Record, August 31, 1979

Montreal Star, March 14, 1979

Montreal Star, March 14, 1979Frustré par le manque de coopération qu’il recevait de la police locale et de l’administration du Collège Champlain à la suite de la disparition de Thérèsa, mon père a embauché Robert Beullac. Si Beullac croyait que son conflit avec la SQ n’entraverait pas son travail sur le cas de Theresa, il se trompait complètement. Plutôt que de percer le brouillard de sa disparition, la présence imposante de Beullac sur le terrain était un obstacle de plus qui a gêné une enquête en bonne et due forme – peu importe de toute façon, car nous voyons maintenant que la SQ (ou QPF en anglais les appelait) avaient peu d’intérêt à résoudre les crimes contre les femmes. Charles Marion était un gros problème. Raymond Grimard était un grand fromage. Mais Manon Bergeron qui a été retrouvée avec lui était la cinquième affaire en ce qui concerne la police, le plus souvent qualifiée de «concubine» ou de «sa pute» de Grimard. Et Carole Fecteau ? Comme je l’ai dit, le vrai jetsam du crime, une réflexion après coup. A-t-elle même obtenu un procès? Nous y viendrons.

Corrupt Cops – Robert Beullac

Corrupt Cops – Robert BeullacL’acrimonie entre Beullac et la police était si corrosive qu’ils ne supportaient même pas d’être dans la même pièce ensemble, et feignaient au moins la civilité et la coopération face au stress et au chagrin que subissaient mes parents. Une fois, j’ai fait remarquer à Bob une rencontre entre mes parents, le chef de police de Lennoxville Leo Hamel et le caporal de la SQ Roch Gaudreault qui a eu lieu au Hilton de l’aéroport de Montréal à l’occasion du premier anniversaire de sa disparition. J’ai suggéré par erreur que le détective privé était également là, ce à quoi Beullac a répondu: “Non, cela ne s’est jamais produit”. Quand je lui ai demandé comment il en était si sûr, il a répondu catégoriquement: “Parce que si Rocky avait franchi la porte d’entrée du Hilton, je me serais immédiatement levé et je serais sorti par la porte arrière.”

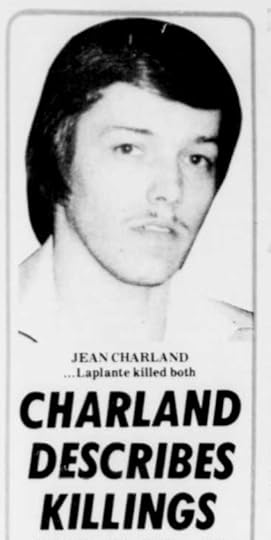

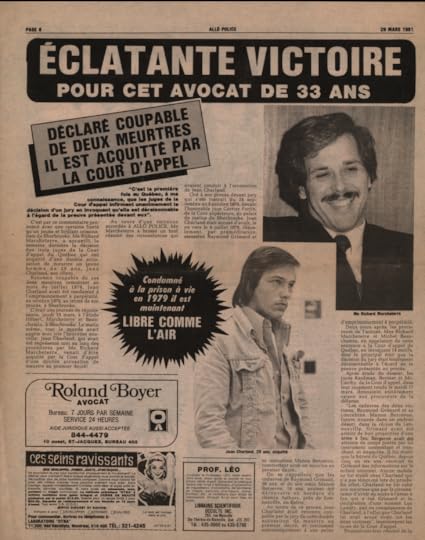

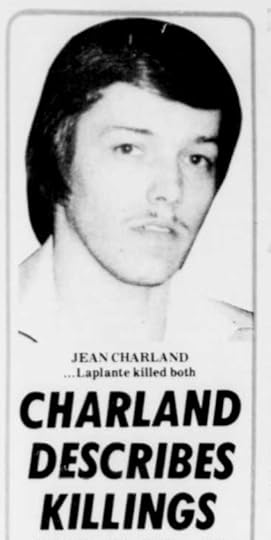

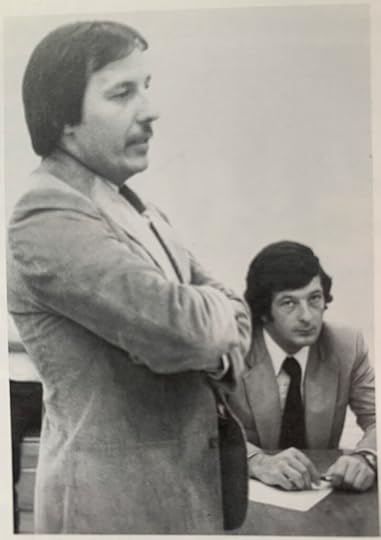

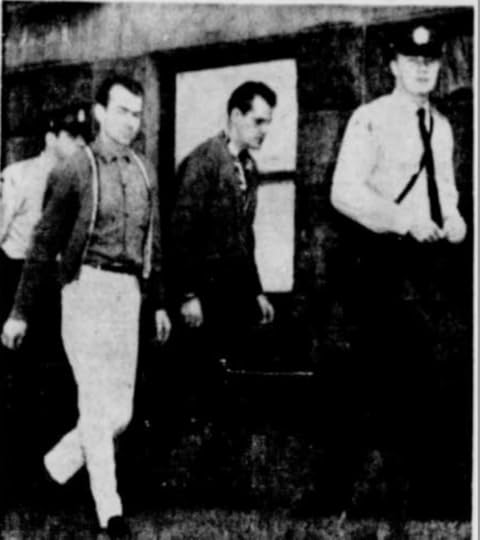

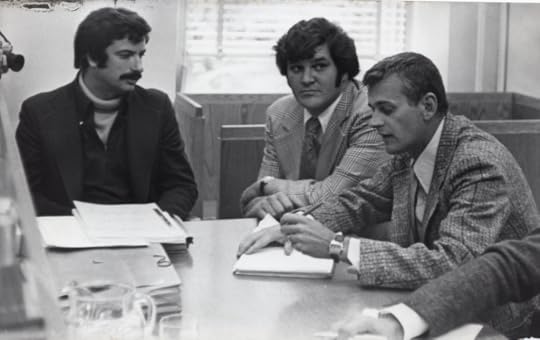

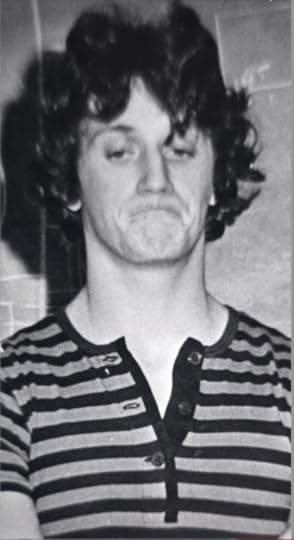

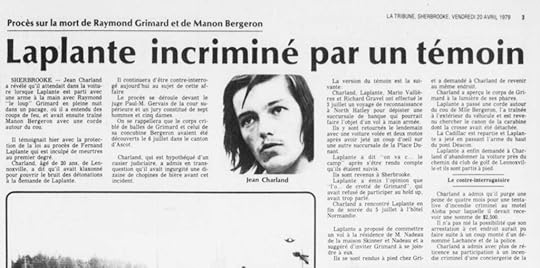

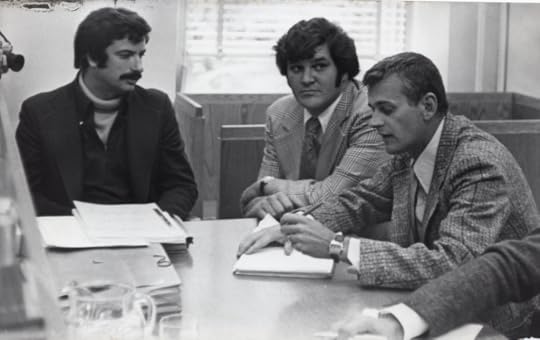

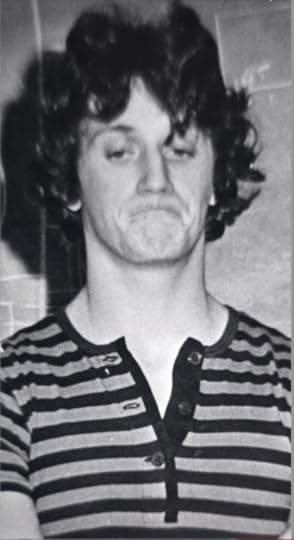

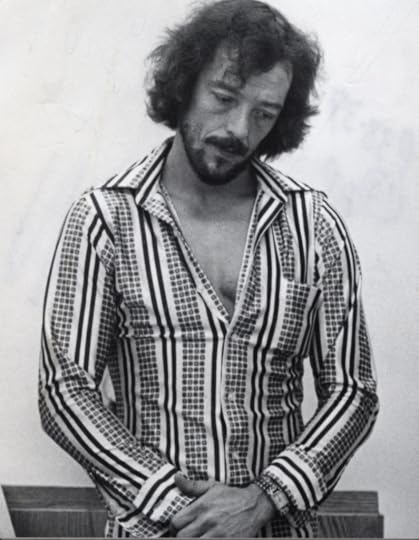

Procès Charland Jean Charland cleaned himself up for his trial

Jean Charland cleaned himself up for his trialLe procès de Jean Charland pour les meurtres au premier degré de Raymond « le loup » Grimard et de Manon Bergeron est finalement entendu à l’automne 1979, cinq mois après la condamnation de son soi-disant complice, Fernand Laplante qui purgeait alors sa peine à perpétuité. pour les meurtres. Bon nombre des mêmes personnages ont été amenés devant le juge Carrier Fortin. Une matinée entière a été consacrée au dossier juvénile de Luc Landry, comment à 16 ans il a braqué une Compton Credit Union et sa condamnation à Thunder Bay pour défaut de payer un sandwich.

L’officier de la SQ Réal Chateauneuf a témoigné avoir récupéré une bille de bouleau le 8 janvier 1979 sous un escalier au sous-sol de la maison de Charland à Lennoxville qui contenait 69 cartouches. Une cartouche qui a réussi à être identifiable correspondait à quatre cartouches récupérées sur le corps de Grimard. Difficile d’imaginer pourquoi Charland ressentirait le besoin de dissimuler des preuves qui pointaient vers un nous apon utilisé, selon la police et Charland, par Laplante pour abattre Grimard. Rappelons que d’après le propre témoignage de Charland, l’arme du crime aurait été récupérée chez lui le soir des meurtres, mais ensuite utilisée par Laplante.

Le 3 octobre 1979, exactement 11 mois après la disparition de Thérèse Allore, Jean Charland est également condamné à la réclusion à perpétuité pour les meurtres de Grimard et Bergeron. Il est difficile de comprendre pourquoi. Il n’y avait qu’une seule arme utilisée pour tirer sur Grimard. Le problème était simple, soit Charland lui a tiré dessus, soit Laplante, mais pas les deux. La justice de Sherbrooke semblait travailler sous l’angle suivant : “Eh bien, quelque chose comme ça s’est produit, alors condamnons-les tous les deux et passons à autre chose.”

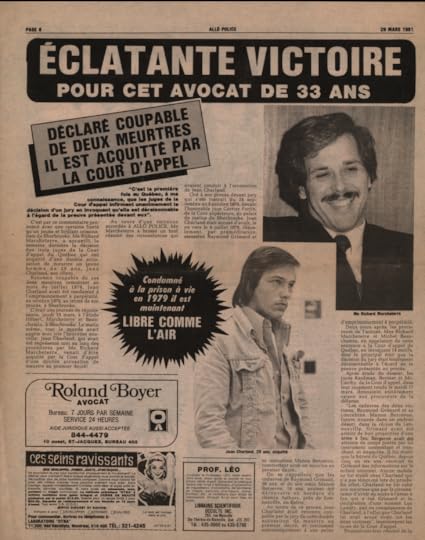

L’avocat de Charland, Richard Marcheterre, a demandé une révision. Mais contrairement à Laplante, l’appel de Charland a rencontré un résultat très différent. La preuve de la poursuite reposait sur leur principal témoin, le témoignage de Luc Landry sur la façon dont Charland lui avait raconté au Moulin Rouge comment il avait « pimenté Grimard » dans une ruelle de la rue Wellington. En 1981, la Cour d’appel du Québec infirme le jugement et Charland est libéré. Les trois juges du comité d’appel considéraient le témoignage de Landry comme du ouï-dire (n’était-ce pas le témoignage de Charland contre le ouï-dire de Laplante ?) et “pensaient à l’unanimité que rien dans la preuve ne reliait Charland aux victimes”. Je suppose qu’ils avaient besoin de plus de points pour se connecter que le fusil utilisé pour assassiner Grimard caché dans la maison de Charland, et ce journal.

Allo Police, 29 Mars, 1981

Allo Police, 29 Mars, 1981Il s’agit d’une victoire sans précédent pour le jeune avocat de Charland, Richard Marcheterre, qui a déclaré que « c’était la première fois au Québec qu’il se souvenait que les juges avaient pris une décision à l’unanimité au motif que la preuve était déraisonnable ». La Tribune a rapporté qu’il était “extrêmement rare que la Cour d’appel annule un verdict de cette manière, ordonnant plutôt un nouveau procès dans de nombreux cas”. Rare en effet, quels « inconnus » sont intervenus en faveur de Charland ? Allo Police écrivait sèchement que Charland avait été « libéré comme l’air », et il l’était donc. Alors que Fernand Laplante languit à la prison de Dorchester pendant plus de 40 ans, Charland est retourné à sa routine habituelle d’incendies criminels et de vols à Lennoxville, et la communauté a fermé les yeux sur tout cela.

Le jour même où la condamnation de Charland a été annulée, et dans ce que la Sûreté du Québec a dû considérer comme un fait accompli, La Tribune rapporte que la Commission de Police du Québec a rejeté les plaintes déposées par Robert Beullac pour inconduite policière lors du procès Laplante. Beullac pestait depuis deux ans que Jean Charland avait obtenu l’immunité en échange de son témoignage contre Laplante. Personne n’a écouté. Dans ce que La Tribune a qualifié de « dernières gouttes du flot de plaintes » contre la SQ, la Commission de police a déterminé qu’il n’y avait pas lieu à une enquête publique et a demandé à la Police du Québec d’essayer d’éviter des actes « d’imprudence » à l’avenir.

Robert Beullac demands Justice probe“Nous attendons””

Robert Beullac demands Justice probe“Nous attendons””Jean Charland a repris là où il s’était arrêté et, au cours de la décennie suivante, il est devenu plus une nuisance publique qu’une menace pour les Cantons. Moins de 7 mois après son acquittement et près de 3 ans jour pour jour après la disparition de Theresa Allore, Jean et son frère cadet, Marc Charland (l’ancien petit ami de Carol Fecteau) ont été arrêtés pour avoir brisé la vitre avant du Sinclair Bowling Alley juste au nord du Moulin Rouge. L’agent Rodrigue a rattrapé les frères dans une ruelle de Wellington, caché sous un escalier en fer. Lorsqu’on leur a demandé ce qu’ils faisaient, ils ont répondu: “rien, nous attendons”. Imaginez l’excitation de Richard Marcheterre lorsqu’il s’est également vu confier cette affaire (voir carte, la rue Wellington est à court d’immobilier).

Quatre mois plus tard, en mars 1982, Charland est de nouveau devant le tribunal, cette fois pour s’être introduit par effraction dans le restaurant de son père, Chez Charles, sur la rue Queen à Lennoxville. Il était maintenant parti depuis longtemps avec la coiffe disco qu’il arborait lors de son procès pour meurtre, retombant sur les cheveux longs et une veste en jean alors qu’il faisait face au magistrat. Lorsqu’Ivan Charland s’aperçoit qu’il manque 680 $ à la caisse, il fait arrêter son fils par le chef de la police de Lennoxville, Léo Hamel. Le zélé Hamel a même mené une enquête avec la collaboration de deux agents de la Sûreté du Québec. Charland venait tout juste d’être mis en probation pour un autre cambriolage d’un garage des Cantons. Charland avait alors un nouvel avocat, Michel Beauchemin, qui a plaidé auprès du juge Roberge pour qu’il considère que Charland était aux prises avec un problème de drogue et d’alcool. Le procureur Claude Mélançon (vous vous souvenez de lui du procès de Laplante?), a déclaré que la boisson n’était pas pertinente et que Charland avait violé sa probation. La Tribune n’a pas tardé à noter que l’appel de Fernand Laplante à la Cour suprême du Canada avait été rejeté, tandis que Charland – accusé des mêmes meurtres – a été libéré par un tribunal inférieur du Québec. Pour les Cantons, Jean Charland était devenu le cadeau qui ne cessait de donner.

Je PenseJe ne suis pas un génie de l’investigation, je simple possèdent de bonnes capacités d’analyse et sont capables, parfois, de décomposer et de rassembler d’énormes quantités d’informations complexes. Lors de l’examen des suspects dans le cas de ma sœur, cela semblait une assez bonne hypothèse de ne pas se concentrer sur les personnes qui avaient récemment été accusées ou condamnées pour des crimes similaires. Je pensais que le processus judiciaire les éliminerait pour examen, ils étaient maintenant passés devant les tribunaux et étaient soit en prison, soit sous l’œil vigilant de la police. Ou alors vous supposeriez, non?

Ce genre de raisonnement s’effondre lorsqu’on considère quelqu’un comme Jean Charland, et un corps policier comme la Sûreté du Québec qui défie complètement la logique. L’argument est que Charland n’aurait pas participé au meurtre de Theresa parce qu’il était sur la piste d’un meurtre précédent, et donc en prison, n’est-ce pas ? Sauf qu’il n’était pas en prison, il était libre. Il vivait dans la maison de ses parents à Lennoxville (où Theresa a été vue pour la dernière fois) et il a échappé à l’attention jusqu’à la nuit de l’incendie du motel Aloha, le 10 novembre, une semaine après la disparition de Theresa. Comment la police a-t-elle pu passer à côté d’un détail aussi important ? A moins qu’ils ne veuillent pas attirer l’attention dessus. Ils ne voulaient pas que cela soit remarqué par qui que ce soit.

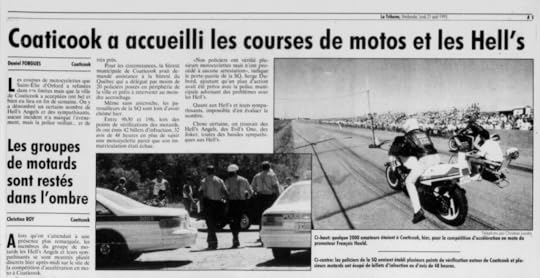

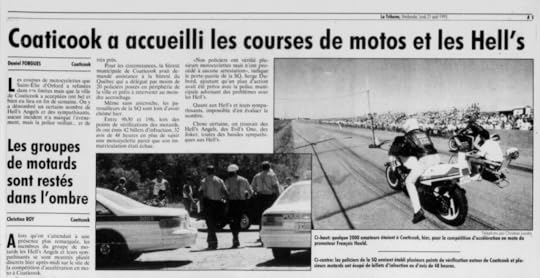

“Là pour voir des motos”Il y avait une histoire qui a couru à La Tribune l’été 1995 à propos d’une compétition de motos qui se déroulait pendant un long week-end, et la crainte locale que des gangs de motards comme les Hells Angels pourraient l’envahir. C’est une vieille histoire, ces cris de vigilance reviennent de temps en temps. Vingt-cinq ans plus tôt, pratiquement le même article avait paru dans La Tribune à propos d’une compétition estivale de vélo impliquant les Gitans, les précurseurs des Hells. Boy-Boy Beaulieu a même été interviewé, on en parlait dans Père Jean Salvail, Le Curé Motard de Sherbrooke.

La Tribune, 21 Aout, 1995

La Tribune, 21 Aout, 1995Le reporter Daniel Forgues a sondé le public pour vérifier la température des participants, et il a interviewé un dénommé Jean Charland, un « fan », présent toute la journée de compétition :

“J’étais assis juste à côté d’un gars des Evil Ones, je ne l’ai pas dérangé, et il a fait pareil. Et je ne me suis pas empêché de crier et de raconter des blagues à leur sujet. Eux aussi sont là pour voir des motos »

“Coaticook a accueilli les courses de motos et les Hell’s”, Daniel Forgues, La Tribune, 21, Aout, 1995

Bien sûr, il est utile d’être si complaisant sur ces questions si vous êtes vous-même un membre connecté des Hells Angels. Si en fait c’était notre Jean Charland.

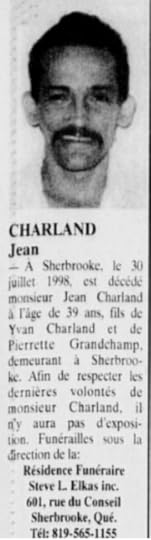

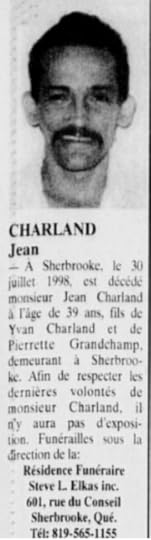

Les Gitans Jean Charland – celui impliqué dans les meurtres de 1978, qui a mis le feu au motel Aloha, qui est devenu un vagabond public – est décédé trois ans plus tard à Sherbrooke le 30 juillet 1998. Il avait 39 ans. Il en paraissait 60. On m’a dit que il est mort du SIDA. S’il avait autre chose à dire sur ce qui s’est passé dans les Cantons-de-l’Est en 1978, il a emporté ses secrets avec lui. Il n’y a pas eu de confession sur le lit de mort.

Nécrologie de Jean Charland, 30 juillet 1998Les motards de la Colombie-Britannique

Nécrologie de Jean Charland, 30 juillet 1998Les motards de la Colombie-BritanniqueTrès tôt quand j’ai commencé ce site, j’ai écrit sur l’affaire Fernand Laplante. J’ai lu à ce sujet dans un almanach annuel Allo Police, et j’ai posté les photos de Laplante, Charland, Grimard, Bergeron et Beullac, typographiques avec un fond rouge criard (donc Allo), vers le début des années 2000. Presque immédiatement, j’ai reçu un appel de mon père me demandant de tout démonter.

Il m’a dit qu’un vieil ami de collège à lui, qui avait été ami avec Laplante, avait été contacté par des « gens de la Colombie-Britannique ». Lorsque je lui ai demandé de qui il s’agissait, il est devenu évident qu’il faisait référence à des membres du crime organisé, des motards que l’ami de l’université connaissait, qui ont suggéré qu’il serait dans mon intérêt que je n’écrive pas sur de telles choses. Je suis un fils obéissant, alors j’ai fait ce qu’on m’a dit, j’ai noté l’histoire. Je noterai qu’en 1978, mes parents n’avaient aucune connaissance des meurtres survenus plus tôt dans l’année précédant la disparition de Theresa ; pas Grimard et Bergeron, pas Fecteau, ni même Manon Dubé. Cette information leur a été cachée par la police, et ils vivaient à l’extérieur du Québec, leurs nouvelles locales n’auraient pas couvert les histoires. Il est douteux que la police ait même fait le lien avec ces cas eux-mêmes à l’époque, n’est-ce pas ? Nous verrons.

Des années plus tard, juste avant sa mort, j’ai interrogé mon père sur cet épisode. À ce moment-là, son ami d’université était décédé, alors j’espérais obtenir plus d’informations, peut-être la véritable nature de son envie. Mais mon père a changé l’histoire. Ce n’était pas des motards de la Colombie-Britannique, c’était simplement que l’ami du collège avait connu Fernand Laplante, et maintenant qu’il était en liberté conditionnelle, il voulait voir qu’il prenait un nouveau départ, il n’avait pas besoin que je drague le passé. Il vaudrait mieux que je ne parle pas de telles choses et que je laisse le passé à la mémoire.

Mon père n’a menti que dans des circonstances rares et exceptionnelles. Ce n’est pas ma mémoire qui est défaillante, je sais ce qu’il a dit la première fois.

Jean Charland – Prodigal Son

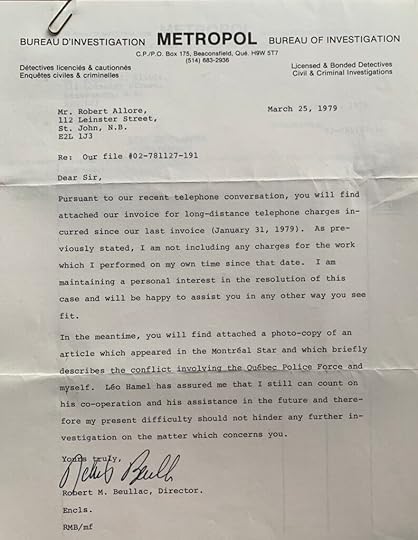

“March 25, 1979

Dear Mr. Allore,

… you will find attached a photo-copy of an article which appeared in the Montreal Star and which briefly describes the conflict involving the Quebec Police Force and myself. Leo Hamel has assured me that I still can count on his co-operation and his assistance in the future and therefore my present difficulty should not hinder any further investigation on the matter which concerns you.

Yours Truly.

Robert M. Beullac, Director, Metropol Bureau of Investigation”

At the conclusion of Fernand Laplante’s trial, the Surete du Quebec had Private Investigator Robert Beullac arrested for impersonating a police officer to residents of Astbury Road during the experiment where he proved that a gun was not fired at the location the night of the Grimard and Bergeron murders.

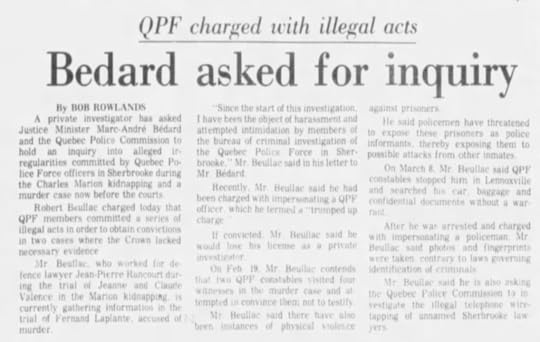

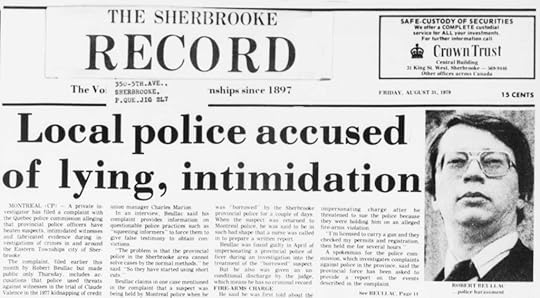

The charges were retaliation for Beullac having filed a complaint with the Quebec Police Commission alleging that “provincial police officers had beaten suspects, intimidated witnesses and fabricated evidence during investigations of crimes in and around the Eastern Townships city of Sherbrooke.” Beullac had documented several beatings by the SQ against Townships residents. Specifically he cited SQ investigators for having savagely beaten Fernand Laplante on several occasions during his initial arrest between August 3 and 5, 1978. He charged that the Surete du Quebec engaged in “acts of brutality, intimidation towards defense witnesses” elaborating that an investigator had twisted the breasts of Laplante’s wife, Claire Dussault. Beullac further alleged investigators made inappropriate, casual conversation with the jury during Laplante’s trial. Robert Beullac was just one of many in a long queue of Quebecers demanding justice from Minister Marc-Andre Bedard in 1979. The father of Diane Dery (murdered with Mario Corbeil) petitioned Bedard over his daughter’s botched investigation. Before the close-out of that year Bedard had to order an investigation into the SQ police shooting of on the Kahnawake Reserve south of Montreal.

“The problem is that the provincial police in the Sherbrooke area cannot solve cases by the normal methods… so they have started using short cuts “

“Local police accused of lying, intimidation”, Sherbrooke Record, August 31, 1979

Montreal Star, March 14, 1979

Montreal Star, March 14, 1979Frustrated by the lack of cooperation he was receiving from local police and Champlain College administration in the wake of Theresa’s disappearance, my father hired Robert Beullac. If Beullac believed his conflict with the SQ wouldn’t hinder his work on Theresa’s case he was dead wrong. Rather than cutting through the fog of her disappearance, Beullac’s imposing presence in the field was one more obstacle that got in the way of a proper investigation – not that that matter much anyway, as we now see that the SQ (or QPF as the English called them) had little interest in solving crimes against women. Charles Marion was a big deal. Raymond Grimard was big cheese. But Manon Bergeron who was found with him was fifth business as far as the police were concerned, most often referred to as Grimard’s “concubine” or his “bitch”. And Carole Fecteau? As I’ve said, true crime jetsam, an afterthought. Did she even get a trial? We’ll come to that.

Corrupt Cops – Robert Beullac

Corrupt Cops – Robert BeullacThe acrimony between Beullac and police was so corrosive, they couldn’t even stand to be in the same room together, and at least feign civility and cooperation in the face of the stress and grief my parents were under. I once remarked to Bob about a meeting that occurred between my parents, Lennoxville Police Chief Leo Hamel and SQ Caporal Roch Gaudreault that took place at the Montreal Airport Hilton on the one-year anniversary of her disappearance. I mistakenly suggested that the private detective had been there as well, to which Beullac interjected, “No, that never happened”. When I asked him how he was so sure, he replied flat, “‘Cause if Rocky walked in the front door of the Hilton, I would have immediately got up and walked out the back door.”

When the log rolls overJean Charland’s trial for the first-degree murders of Raymond “the Wolf” Grimard and Manon Bergeron was finally heard in the fall of 1979, five months after the conviction of his so-called accomplice, Fernand Laplante who by now was serving his life sentence for the murders. Many of the same cast of characters were brought before Judge Carrier Fortin. An entire morning was spent on Luc Landry’s juvenile record, how at 16 he held up a Compton Credit Union, and his Thunder Bay conviction for failure to pay for a sandwich.

SQ officer Réal Chateauneuf testified that he recovered a birch log on January 8, 1979 under a staircase in the basement of Charland’s home in Lennoxville which contained 69 rounds of ammunition. One round that managed to be identifiable matched four rounds recovered from Grimard’s body. Hard to imagine why Charland would feel the need to conceal evidence that pointed to a weapon used, according to police and Charland, by Laplante to gun down Grimard. Recall that from Charland’s own testimony, the murder weapon would have been retrieved from his house on the night of the murders, but then used by Laplante.

Jean Charland cleaned himself up for his trial

Jean Charland cleaned himself up for his trialOn October 3, 1979, exactly 11 months after the disappearance of Theresa Allore, Jean Charland was also sentenced to life imprisonment for the murders of Grimard and Bergeron. It’s hard to understand why. There was only one weapon used to shoot Grimard. The issue was simple, either Charland shot him or Laplante, but not both. Sherbrooke justice seemed to be working an angle of, “Well, something like this happened, so let’s convict them both and move on.”

Charland’s lawyer, Richard Marcheterre, requested a review. But unlike Laplante, Charland’s appeal was met with a very different outcome. The prosecution’s case hinged on their chief witness, Luc Landry’s testimony of how Charland had told him at the Moulin Rouge how he “peppered Grimard” in an alley along Wellington Street. In 1981 The Quebec Court of Appeal overturned the judgement and Charland was set free. The three judges on the appeal board regarded Landry’s testimony as hearsay (wasn’t Charland’s testimony against Laplante hearsay?), and “unanimously believed that nothing in the evidence linked Charland to the victims”. I guess they needed more dots to connect than the rifle used to murder Grimard stashed in Charland’s house, and that log.

Allo Police, 29 Mars, 1981

Allo Police, 29 Mars, 1981It was an unprecedented victory for Charland’s youthful attorney, Richard Marcheterre, who commented “it was the first time in Quebec he remembered that the judges unanimously came to a decision on the grounds that the evidence was unreasonable.” La Tribune reported that it was “extremely rare for the Court of Appeal to reverse a verdict in this way, ordering a new trial in many cases instead.” Rare indeed, what “unknown persons” intervened on Charland’s behalf? Allo Police dryly wrote that Charland had been “liberated like air”, and so he was. While Fernand Laplante languished in Dorchester Prison for over 40 years, Charland went back to his regular Lennoxville routine of arsons and robberies, and the community turned a blind eye to it all.

On the same day that Charland’s conviction was overturned, and in what the Surete du Quebec must have considered a fait accompli, La Tribune reported that the Quebec Police Commission dismissed complaints made by Robert Beullac of police misconduct during the Laplante process. Beullac had been railing for two years that Jean Charland had been granted immunity in exchange for his testimony against Laplante. Nobody listened. In what La Tribune called “the last drops of the flood of complaints” against the SQ, the Police Commission determined there were no grounds for a public inquiry, and asked Quebec Police to try and avoid acts of “recklessness” in the future.

Robert Beullac demands Justice probe“We are waiting”

Robert Beullac demands Justice probe“We are waiting”Jean Charland picked up where he had left off, and for the next decade became more of a public nuisance than a menace to the Townships. Less than 7 months after his acquittal and almost 3 years to the day of Theresa Allore’s disappearance, Jean and his younger brother, Marc Charland (the one time boyfriend of Carol Fecteau) were arrested for for smashing the front glass of the Sinclair Bowling Alley just north of the Moulin Rouge. Constable Rodrigue caught up with the brothers in a Wellington alley hiding under an iron staircase. When asked what they were doing, they replied, “nothing, we are waiting.” Imagine Richard Marcheterre’s excitement when he was also handed this case (see map, Rue Wellington is running out of real estate).

Four months later, in March 1982, Charland was back in court again, this time for breaking into his father’s restaurant, Chez Charles on Lennoxville’s Queen Street. By now he had long departed with the disco coif he sported during his murder trial, falling back on long hair and a jean jacket as he faced the magistrate. When Ivan Charland noticed $680 missing from the till, he had Lennoxville Police Chief Léo Hamel arrest his son. The zealous Hamel even conducted an investigation with the cooperation of two Surete du Quebec agents. Charland had only just been placed on probation for another burglary of a Townships garage. By now Charland had a new attorney, Michel Beauchemin, who pleaded with Judge Roberge to consider that Charland was dealing with a drug and alcohol problem. Prosecutor Claude Mélançon (remember him from Laplante’s trial?), said that drink was irrelevant, and Charland had violated his probation. La Tribune was quick to note that Fernand Laplante’s appeal to the Supreme Court of Canada had been denied, while Charland – accused of the same murders – was set free by a lower, Quebec court. For the Townships, Jean Charland had become the gift that kept on giving.

No shit, SherlockI am no investigative genius, I simply possess good analytical skills, and am able to, sometimes, take apart and reassemble massive amounts of complex information. When considering suspects in my sister’s case, it seemed a fairly good assumption that you would not focus on persons who had recently been accused or convicted of similar crimes. My thinking was that the justice process would eliminate them for consideration, they had now transitioned to the courts and were either in jail or prison, or under the watchful eye of police. Or so you’d assume, right?

That sort of reasoning collapses when considering someone like Jean Charland, and a police force like the Surete du Quebec who completely defy logic. The arguement goes that Charland would not have been party to Theresa’s murder because he was on trail for a previous murder, and therefore in jail, right? Except he wasn’t in jail, he was free. He was living at his parents’ house in Lennoxville (where Theresa was last seen) and he escaped notice until the night of the Aloha Motel fire, November 10, one week after Theresa’s disappearance. How could the police miss such an important detail? Unless they didn’t want to call attention to it. They didn’t want it to be noticed by anyone.

“There to see motorcycles”There was a story that ran in La Tribune the summer of 1995 about a motorcycle competition that was occurring over a long weekend, and local concern that biker gangs like The Hells Angels might be overrunning it. It is an old story, these cries for vigilance crop up from time to time. Twenty-five years earlier practically the same article ran in La Tribune about a summer bike competition that involved The Gitans, the forerunners of the Hells. Boy-Boy Beaulieu was even interviewed, we talked about this in Father Jean Salvail, The Biker Priest of Sherbrooke.

La Tribune, 21 Aout, 1995

La Tribune, 21 Aout, 1995Reporter Daniel Forgues canvassed the audience to check the temperature of participants, and he interviewed someone named Jean Charland, a “fan”, attending the entire day of competition:

“I was sitting right next to a guy from the Evil Ones, I didn’t bother him, and he did the same. And I didn’t stop myself from yelling and telling jokes about them. They too are there to see motorcycles”

“Coaticook a accueilli les courses de motos et les Hell’s”, Daniel Forgues, La Tribune, 21, Aout, 1995

Of course, it helps to be so complacent about these matters if you yourself are a connected member of The Hells Angels. If in fact this was our Jean Charland.

The Gitans Jean Charland – the one involved in the 1978 murders, who set the Aloha Motel fire, who became a public vagrant – died three years later in Sherbrooke on July 30, 1998. He was 39. He looked 60. I was told that he died of AIDS. If he had anything further to say of what went on in the Eastern Townships in 1978, he took his secrets with him. There was no death bed confession.

Jean Charland obituary, 30 Juillet, 1998The Bikers of BC

Jean Charland obituary, 30 Juillet, 1998The Bikers of BCVery early on when I started this website I wrote about the Fernand Laplante affair. I read about it in a Allo Police annual almanac, and posted the photos of Laplante, Charland, Grimard, Bergeron, and Beullac, typefaced with a garish red background (so Allo), sometime around the early 2000s. Almost immediately, I got a call from my father asking me to take it all down.

He told me an old college friend of his, who had been friends with Laplante, had been contacted by some “people in British Columbia”. When I pressed him on who this was, it became obvious that he was referring to members of organized crime, bikers who the college friend was acquainted with, who suggested it would be in my best interest if I did not write about such things. I’m an obedient son, so I did what I was told, I took the story down. I will note that in 1978, my parents had no knowledge of any of the murders that had occurred earlier in the year prior to Theresa’s disappearance; not Grimard and Bergeron, not Fecteau, or even Manon Dube. This information was withheld from them by police, and they were living outside of Quebec, their local news would not have covered the stories. It’s doubtful police even made the connection with these cases themselves at the time, or is it? We shall see.