Stewart Brand's Blog, page 62

November 27, 2013

A 75-year Study on the Secrets to Happiness

The credit for growing old with grace and vitality, it seems, goes more to ourselves than to our stellar genetic make-up.

So concludes the synopsis of Triumphs of Experience, the latest book to come out of the Harvard Grant Study, an ambitious and comprehensive project that has tracked the life course of 268 male members of the Harvard classes of 01938 – 01940 for seventy-five years now.

The study began in 01938 as an effort to examine optimal human health: unlike ordinary medical studies at the time, the project’s directors were interested not in what made people sick, but rather in what caused them to thrive. Since then, teams of researchers have tracked an enormous amount of variables in the lives of their subjects. They’ve conducted regular physiological examinations and laboratory measurements, as well as IQ tests, personal interviews, and psychiatric evaluations. They’ve even spoken with the study participants’ parents, wives, and children.

There are other longitudinal studies that rival this one in length, but George Vaillant, the study’s director from 01972 to 02004, explains that none are as comprehensive as the Harvard Grant Study:

… what makes the Grant Study unique is that the men have given us permission to present their lives in three dimensions, so that the book is not only about statistics, but it’s about stories. The book is the history of how the men, and the science, and its author changed from a pre-World War II view of the world, to the way we see it in 02012.

Funded by a variety of sources over the years, the study offers a comprehensive history of individual lives (including that of John F. Kennedy, a study participant until his assassination fifty years ago), but also of the advances we’ve made in research methodologies and data collection: its files are stored in a variety of media, from the IBM punch cards used during the project’s first years, to the digital spreadsheets used today.

A first comprehensive report on the study was published in 01998, when participants were in their late 50s. Triumphs of Experience extends that portrait into the men’s old age, but still conveys the same basic message: happiness and professional success have little to do with status or income, and everything with the warmth and stability of your interpersonal relationships. What Vaillant emphasizes is that the course of our lives is not determined by the hardships we encounter, but by the resilience we show in the face of adversity – and the more connected we are with others, the better we are at coping with life’s difficulties.

Of course, a group of male Harvard undergraduates, particularly those of the late 01930s, is unlikely to be representative of the general US population – let alone of the rest of the world. Still, there are lessons to be drawn from this study. Not the least of these is the reminder that some of the most profound insights into the nature and experience of human life cannot be found through quick, narrow experiments: they require the dedication and patience of a long-term, multi-generational project.

November 26, 2013

Internet Archive Fundraiser – Lost Landscapes of San Francisco 8 – 2nd Showing

Now in its eighth year, Rick Prelinger’s Lost Landscapes of San Francisco is almost always the largest of our Seminars About Long-term Thinking. Pre-sale tickets have sold out again at the Castro Theater and a few tickets will be released to the walk up line on the day of the show.

Those who didn’t get tickets to the December 17th event, though, have another chance to catch this great show. Rick is screening it again at the Internet Archive the following night, Wednesday December 18th and this show is a fundraiser for the Internet Archive.

The Internet Archive recently lost a lot of equipment and many books to a fire. Fortunately, no one was hurt, but the expenses incurred to replace and repair what was damaged will be significant. Rick Prelinger has generously offered this second screening of Lost Landscapes of San Francisco 8 and proceeds will go to the Internet Archive’s efforts to rebuild the scanning facility where the fire took place.

Lost Landscapes of San Francisco: Fundraiser Benefitting Internet Archive

December 18, 02013 at 6:30 PM

Detail and Tickets

November 22, 2013

Richard Kurin Seminar Media

This lecture was presented as part of The Long Now Foundation’s monthly Seminars About Long-term Thinking.

This lecture was presented as part of The Long Now Foundation’s monthly Seminars About Long-term Thinking.

American History in 101 Objects

Monday November 18, 02013 – San Francisco

Audio is up on the Kurin Seminar page, or you can subscribe to our podcast.

*********************

American objects – a summary by Stewart Brand

Figuratively holding up one museum item after another, Kurin spun tales from them. (The Smithsonian has 137 million objects; he displayed just thirty or so.)

The Burgess Shale shows fossilized soft-tissue creatures (“very early North Americans”) from 500 million years ago. The Smithsonian’s Giant Magellan Telescope being built in Chile will, when it is completed in 2020, look farther into the universe, and thus farther into the past than any previous telescope—12.8 billion years.

Kurin showed two versions of a portrait of Pocahontas, one later than the other. “You’re always interrogating the objects,” he noted. In the early image Pocahontas looks dark and Indian; in the later one she looks white and English.

George Washington’s uniform is elegant and impressive. He designed it himself to give exactly that impression, so the British would know they were fighting equals.

Benjamin Franklin’s walking stick was given to him by the French, who adored his fur cap because it seemed to embody how Americans lived close to nature. The gold top of the stick depicted his fur cap as a “cap of liberty.” Kurin observed, “There you have the spirit of America coded in an object.”

In 1831 the first locomotive in America, the “John Bull,” was assembled from parts sent from England and took up service from New York to Philadelphia at 15 miles per hour. In 1981, the Smithsonian fired up the John Bull and ran it again along old Georgetown rails. It is viewed by 5 million visitors a year at the American History Museum on the Mall.

The Morse-Vail Telegraph from 1844 originally printed the Morse code messages on paper, but that was abandoned when operators realized they could decode the dots and dashes by ear. In the 1840s Secretary of the Smithsonian Joseph Henry collected weather data by telegraph from 600 “citizen scientists” to create: 1) the first weather maps, 2) the first storm warning system, 3) the first use of crowd-sourcing. The National Weather Service resulted.

Abraham Lincoln was 6 foot 4 inches. His stylish top hat made him a target on battlefields. It had a black band as a permanent sign of mourning for his son Willie, dead at 11. He wore the hat to Ford’s Theater on April 14, 1865. When you hold the hat, Kurin said, “you feel the man.”

In 1886 the Smithsonian’s taxidermist William Temple Hornaday brought one of the few remaining American bison back from Montana to a lawn by the Mall and began a breeding program that eventually grew into The National Zoo. His book, The Extermination of the American Bison, is “considered today the first important book of the American conservation movement.”

Dorothy’s magic slippers in The Wizard of Oz are silver in the book but were ruby in the movie (and at the museum) to show off the brand-new Technicolor. The Smithsonian chronicles the advance of technology and also employs it. The next Smithsonian building to open in Washington, near the White House, will feature digital-projection walls, so that every few minutes it is a museum of something else.

Subscribe to our Seminar email list for updates and summaries.

November 20, 2013

The Evolution of Little Red Riding Hood

We in the Western world are not the only ones who grow up with the fairy tale of Little Red Riding Hood.

Stories about young children who face off with a trickster wild animal are told around the world. In East Asia, for example, there is the tale of a tiger who masquerades as an old woman to lure her grandchildren into bed with him. And in parts of sub-Saharan Africa, the evil beast is an ogre who ensnares a young girl by imitating the voice of her brother.

Oral folk tales like these change easily as they are told and retold through generations. They’re fluid, ever-morphing cultural artifacts – and as such, their history and cross-cultural relatedness can be difficult to trace. Nevertheless, an anthropologist at Durham University in the UK has recently shown that it can be done. Borrowing methods that are commonly used in biology to establish evolutionary relationships between species, an analysis conducted by Jamshid Tehrani reveals that these varying narratives are related to one another much like humans are to the Great Apes: they all, ultimately, descend from the same ancestor.

That ancestor, in this case, is a story called “The Wolf and the Kids:” an ancient folktale with European roots, in which a wolf pretends to be a mother goat in order to eat her babies. The Daily Mail quotes Tehrani:

My research cracks a long-standing mystery. The African tales turn out to be descended from The Wolf and the Kids but over time, they have evolved to become more like Little Red Riding Hood, which is also likely to be descended from The Wolf and the Kids. This exemplifies a process biologists call convergent evolution, in which species independently evolve similar adaptations. The fact that Little Red Riding Hood evolved twice from the same starting point suggests it holds a powerful appeal that attracts our imaginations.

Tehrani’s work also contradicts the long-held theory that both Little Red Riding Hood and The Wolf And the Kids originated in East Asia – in fact, he shows, it was the other way around. “Specifically,” the anthropologist says, “the Chinese blended together Little Red Riding Hood, The Wolf and the Kids, and local folk tales to create a new, hybrid story.”

Fairy tales and other stories serve a purpose. They help us make sense of the world and of ourselves, and give us a way to transmit our knowledge and beliefs from generation to generation. As such, Tehrani’s study does more than show that societies around the world and across time have shared their stories with one another: it suggests a certain unity of human psychosocial experience. There must be, out in the world, some real or prospective experience that we are all faced with at some point or other – an experience in which we all seem to find ourselves supported by the narrative theme of young children confronted by a wily wolf.

November 18, 2013

Taking the longpath

Writing for Wired, Ari Wallach contrasts the perspectives that go into building a cathedral that isn’t completed until long after its designer’s death and a McMansion that’s built, foreclosed on and abandoned in less than a generation.

He proposes what he calls the “Longpath,” to encourage more endeavors of the cathedral’s scale:

We need a framework for long-term strategy — one that is visionary yet goal-oriented. Without organising principles, it will be impossible to corral the corporations and capitals of the globe to tackle our significant long-term challenges.

To this end, I suggest “longpath”. It’s a term that connotes long-term and goal-oriented strategies. It can help leaders navigate the balance between short-term gain and long-term ruin.

To further develop this perspective, Reinventors.net is hosting and livestreaming a roundtable discussion with Wallach. Long Now’s executive director Alexander Rose will also take part in the discussion, along with Felicia Wong, Nicole Boyer and Peter Leyden.

This roundtable will bring together an eclectic group to consider how Longpath Thinking might really work. How long is long? Are there better methods for thinking in this way? How would we begin to institutionalize this approach in government and business, the economy and society?

Watch the conversation online on Wednesday November 20th, 02013 at 11:00 am PT.

November 14, 2013

Climate Change and Us: What Does the Future Hold?

Peer beyond the headlines as experts explain what the IPCC report really says about global warming and what it means for our planet and for mankind in a live presentation and discussion on Friday December 13, 02013 at Yerba Buena Center for the Arts in San Francisco.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change will release its fifth major assessment report in 02014. The first working group (of three) has already released their findings on the development and growth of global warming. In short: climate change is not slowing down and humans are a major factor in its acceleration.

swissnex San Francisco, in partnership with The Long Now Foundation, invites the public to hear from a diverse panel of experts on the report’s key takeaways for the scientist, the citizen, and the entrepreneur. Be prepared to come with your questions and join the discussion around short- and long-term strategies for a warming planet. Long Now members receive a discount on tickets, please see your email for instructions on reserving.

The speakers and panelists are:

Susan Burns, Senior Vice President, Global Footprint Network

Saul Griffith, Inventor, Co-founder Otherlab

Paul Hawken, Environmentalist, entrepreneur, journalist, author, professor

Gian-Kasper Plattner, Director of Science, IPCC WGI Technical Support Unit, University of Bern, Switzerland

Thomas Stocker, Co-Chair Working Group I, IPCC

Cost to register is $20, with a $10 discount for Long Now Members

(Check your email for promotional code.)

Friday December 13th, 02013 at the YBCA Forum

A reception for the audience and speakers will follow.

Details and Registration

A 240-Year Old Programmable Computer Boy

In the late 18th century, Swiss clock- and watchmaker Pierre Jaquet Droz decided to advertise his business by building three automata, or mechanical robots, in the shape of young children. Still functional after almost 240 years, the machines are a marvel of mechanical engineering. “The Musician” is a girl who plays an organ – her eyes follow her fingers as they press down on the instrument’s keys, and her chest moves up and down in a breathing motion. “The Draftsman” is a boy who draws four different images – including a portrait of Louis XV.

The most complex of the three, however, is “The Writer.” Constructed with nearly 6,000 components, this mechanical boy sits at a small desk and uses a goose feather quill to write sentences on a piece of paper. Like his Draftsman brother, the Writer’s three-dimensional arm movements are coded by a series of cams: they direct his arm to an inkwell, into which he dips his quill, and then back to his paper, where he writes out letters in a neat cursive script. Professor Simon Schaffer, host of the BBC4 documentary Mechanical Marvels: Clockwork Dreams, explains:

As these cams move, three cam followers read their shaped edges and translate these into the movement of the boy’s arm. Working together, the cams control every stroke of the quill pen, and exactly how much pressure is applied to the paper, so as to achieve beautiful, elegant, and fluid writing. With this sublime machine, Jaquet Droz had reverse-engineered the very act of writing.

But the mechanical boy contained one perhaps even more astonishing feature. The wheel that controlled the cams was made up of letters that could be removed, and then replaced and reordered. These allowed the writer in principle to make any word and any sentence. In other words, it allowed the writer to be programmed. This beautiful boy is thus a distant ancestor of the modern programmable computer.

The Writer is an early example, too, of some of the mechanical technology that runs the 10,000 Year Clock. Of course, the Writer’s system is entirely analog, whereas the Clock incorporates both analog and digital mechanisms (the serial bit adders at the heart of the Orrery provide a binary input for its simulation of planetary movement). Nevertheless, the 18th century automaton is a miniature testimony to what the Clock exemplifies on monument scale: that mechanical systems possess the elegance, the transparency, and the functionality needed to endure across long stretches of time.

November 12, 2013

Rick Prelinger Seminar Tickets

November 11, 2013

A visit to Star Axis

Having climbed the staircase for some time, I stopped on a step that sent me back to the sky of twenty-five hundred years ago, the sky that loomed overhead when the Book of Job was written. I braced myself against the cool stone of the corridor that bracketed the staircase, and looked up through the tunnel. In the 5th century BC, the orbit of Polaris was much further out from the pole than it is now. We know this from our understanding of precession, but also from observations that were recorded at the time, observations that suggest a new way of looking at the sky had begun to emerge by then. Very slowly, it seems, the conceptual filters that humans used to interpret celestial phenomena had started changing, becoming less theological and more empirical. Instead of scanning the sky for the moods and faces of a humanlike god, people began looking for patterns in it. They went searching for order itself in the void.

Aeon Magazine Senior Editor Ross Anderson recently had the privilege of visiting Star Axis, a large-scale architectural installation in the New Mexico desert by artist Charles Ross. Anderson tells the story of his journey to the incomplete and mystery-shrouded artwork, with plenty of backstory on its creator and the astronomical mechanics it highlights.

November 8, 2013

Human Self-Interest and the Problem of Solving Long-Term Issues

We are a selfish, short-sighted lot. As many a game theory experiment has shown, we simply aren’t as motivated by the promise of collective future benefits as we are by the gratification of instant private rewards.

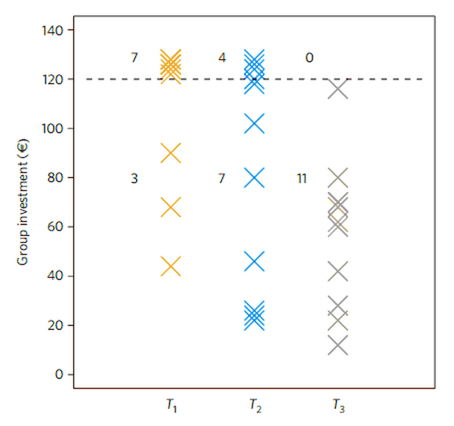

A group of researchers based at NYU now argues that this kind of self-interest can throw up significant hurdles to the process of solving long-term, multi-generational problems like climate change. As reported in the October issue of Nature Climate Change, The team conducted a study that measured participants’ willingness to invest personal resources into a group effort that would lead to rewards in the future: each subject was given €40, and was then asked to deposit €0, €2, or €4 into a collective “climate account” that would fund an environmental awareness advertisement. If each participant deposited enough for the account to reach a total of €120, all would receive an additional €45.

However, the reward of cooperation, the €45 endowment per group member for meeting the €120 target, was distributed on three different time horizons. In one treatment (T1), the €45 cash endowment was paid the next day; in the second treatment (T2), the €45 cash endowment was paid 7 weeks later; in the third treatment (T3), the €45 endowment was invested in planting oak trees that would sequester carbon (as well as provide habitat and greenery) and therefore provide the greatest benefit to future generations, although in a currency different to the monetary endowments offered in T1 and T2.

Just as the scholars hypothesized, participants’ willingness to invest was highest in the T1 scenario, and lowest for T3. In other words: the further a reward lies in the future – and the less likely the individual therefore is to benefit from it himself – the less motivated he is to give his personal resources up for the greater good. The research group concludes:

The results show the power of intergenerational discounting to undermine cooperation …. Immediate monetary rewards seem to matter most. Applying our results to international climate change negotiations paints a sobering picture. Owing to intergenerational discounting, cooperation will be greatly undermined if, as in our setting, short-term gains can arise only from defection. This suggests the necessity of introducing powerful short-term incentives to cooperate, such as punishment, reward or reputation, in experimental research as well as in international endeavours to mitigate climate change.

The article explains that immediate and delayed rewards trigger entirely different parts of the human brain, suggesting that long-term and short-term strategizing involve divergent cognitive processes. It seems, then, that our best chance of fostering a sense of accountability for the future may be to create scenarios in which both parts of the brain are stimulated simultaneously: by coupling the incentive of long-term rewards with that of very short-term consequences.

Stewart Brand's Blog

- Stewart Brand's profile

- 291 followers