Stewart Brand's Blog, page 2

August 30, 2023

The Three-Century Lifespan of the Modern Bee

Two London men explore an assembly of log cabins beneath the South American sun, armed to the teeth with nets and pins. It is the summer of 01845 in the heart of “British Guiana” — a colonized name and government that no longer exists, though the land remains and will remain until all names for it have been forgotten — and the air is alive with the smell of flowers and the hum of insects. For two centuries, Europeans have pillaged this land for all manner of riches: sugarcane and tobacco, coffee and cotton, raised on plantations and tended by the dispossessed indigenous populations and enslaved peoples brought here from Africa.

These two men have also come to take something, though they do so in the name of Western science. Emissaries of the burgeoning discipline of entomology, they stalk the highlands for the huge, black bees whose iridescent wings shimmer like panes of rainbow glass in the tropical sunlight.

Each specimen is gathered, mounted, and labeled with the utmost care. Handwritten tags with the date and locality are added: one man misspells a nearby indigenous landmark, while the other indicates that the pair are just a mile southeast of the larger settlement of Packertown. (Today, in 02023, there are no surviving historical records of this place.) Then, they add their own, unique data. On the back of a pamphlet detailing upcoming passenger ships to the ports, the younger entomologist records the behavior he observes. Almost like a haiku, he writes:

“In barn

at dusk, flying

noisily”

On another, he indicates, “Plucked from cotton, alive, but weak”, and on the third, “hoovering [sic] near roofing boards”. Almost every bee has a unique note, scribbled on a torn corner of a schedule, a newspaper, or the back of the date tag. In two hundred years, we will look back on these records as some of the earliest attempts at insect ethology — the study of behavior — which tell us more about the world and perspective of the entomologists of the 01800s than about the bees they captured.

His companion is equally rigorous, but in a different way. Rather than recording behavior, he scrawls as much minute detail as possible into his tiny scrap, until every bee has a label that reads something similar to “On porterweed flower about 2 meter high on the bank of a creek about 2½ km. southeast of Packertown.” (Typewriters have not yet emerged into common use, but sometime in the early 01900s a student of his student will retype these notes on more durable cardstock.) Four decades from now, detailed accounts such as these will help scientists describe the unique relationship between plants and animals: pollination, the process by which seventy-five percent of flowering plants on the planet reproduce and proliferate. It will finally be understood that insects — treated solely as pests and pestilence-bearers for centuries — are paramount to keeping the world green.

These two will continue their research for several months before returning to London. The jewel of their collection is known to them as Xylocopa cajennae, a huge and magnificent species that will accumulate many other names across the centuries. But the bee itself remains unchanged. It sits, pinned and labeled, in a climate-controlled box, tiny flecks of golden pollen still stuck in the hairs of its abdomen from its morning forage in 01845.

Specimens like these are ghosts of time and space. They — and the people who collected them — have been dead for long over a century. They are suspended in timelessness, and yet not so different from their seventieth-generation descendents: if you watched the iridescent-winged black bees of Guyana today, you would see them alight upon the flowers of porterweed plants, two and a half kilometers southeast of where a busy settlement called Packertown once stood. Even as we fade, we can be assured that the insects will remain, flying noisily at dusk.

In a cluttered study in Maryland of the 01950s, a pair of entomologists — partners in marriage for twenty years, and partners in the field for twenty-five — keep their growing collection of pollinating insects. Many specimens are from their own time together during expeditions across North America, traveling almost nonstop throughout the summer months and filling case upon case with bees from the Appalachian highlands down to the tropical Mexican grassland. The rest of the insects — filling jumbled boxes and cabinets and spilling over the furniture — are inherited from relatives or gifts from colleagues. Their private collection rivals most academic institutions of the time, and spans centuries of entomological field research.

But while it may appear that these specimens are scattered mindlessly about the room, there is a method to this messiness; in their older years, they have started to collect less, and identify more. Together, they sort every bee in their collection, and add a new label to its pin: a determination label, stating the genus and species it belongs to, as well as the year of their decision. Some of these specimens already have tags from the 01920s, and many will receive new ones at the turn of the next century, when the children of this entomologist pair donate their inherited collection to a research institution and the boxes are reopened for the first time in decades.

Three Xylocopa fimbriata specimens showcase the inter-species diversity that makes determination such a difficult artform. Photograph courtesy of the author, specimens courtesy of the University of Michigan Entomology Collections

Three Xylocopa fimbriata specimens showcase the inter-species diversity that makes determination such a difficult artform. Photograph courtesy of the author, specimens courtesy of the University of Michigan Entomology CollectionsFor now, however, these two are at the forefront of their field: insect taxonomy. Like all biologists, they use the Linnaean binomial system of species identification, but unlike Linnaeus, the entomologists of the 01950s have begun to realize that insects cannot be easily categorized by visual similarities alone. Nature journals are flooded with papers that consolidate two former “species” (typically the larger, solid-colored female and smaller, striped male) under the same name, split classifications apart to make room for new organisms to be described, or propose to discontinue a “synonym” — a redundant name for a species that has already been cataloged in Western scientific tradition. The backbone of this boom in taxonomy are collections such as this private Maryland cache, which allow comparison of dozens of individuals from countless insect species across the world. For the first time in history, entomologists can see the staggering, global diversity of insects laid out before their very eyes.

Among this couple’s most important specimens is a bee dated to 01845, labeled Xylocopa cajennae at the time of its collection, from a town they do not recognize in what is still known to them as British Guiana. They set it aside, and, gradually, other black-bodied bees with identical iridescent wings join it in its box. These have their own determination labels dating back several decades, reading: Xylocopa corniger, Megaxylocopa cornuta, Xylocopa fimbriata, and Xylocopa virescens. The entomologists study these specimens carefully. Though some are over a hundred years old, gentle treatment of these insects has kept their body segments, wings, and legs intact and comparable to contemporary individuals. Finally, after analyzing the location data recorded on their tags and the similarities of their morphology, the couple declares the collection to be of the same species. The oldest name — Xylocopa fimbriata — is given precedence; the rest are considered obsolete. In the spring, they publish their findings, alongside a proposition for a new species of American bumblebee: Terrestribombus magnus (by the year of 02014, this will be one of thirteen synonyms for Bombus cryptarum, a species first described in 01775.)

This married pair will publish together dozens of times more during their careers, and their students — women included, despite the hostility of the times — will continue their legacy of naming and renaming their collection, and when it passes into the ownership of a university, the cycle will continue. Science, like all knowledge, is mutable; our understanding of the world(s), ourselves, and the past and the future change every day. Specimens with multiple determination labels prove that our understanding of these creatures is a constant work in progress, evolving with our own ability to study them in increasingly detailed ways through global collaboration and collections, microscopic photography, genetic analysis. It is, in some ways, a representation of thousands of years of human history and curiosity, of the urge to collect and name all the things in the world. The preservation of individual specimens across the centuries allows us to share in that joy of discovery with those who precede us, and those who follow in our footsteps, fixing our names and perhaps creating some new ones of their own.

Technology makes things easier in 02023.

Our lab has a logbook by the door, with names dating back to the 01960s of visitors and their intentions (the research labs itself are far older than that, beginning in 01817 with the founding of the college.) Having one of the largest zoological collections in the world, international experts once traveled from across the globe to study and collaborate under our roof. Nowadays, if a Swiss ichthyologist wants to know the stomach contents of deep-sea fish from the University’s latest expedition, we can send them detailed lists and photos with the click of a button — no eight-hour flights required.

Photographs courtesy of the author, specimens courtesy of the University of Michigan Entomology Collections

Photographs courtesy of the author, specimens courtesy of the University of Michigan Entomology CollectionsBut still, this global collaboration is dependent on the preservation of our physical specimens, kept safe in boxes and cabinets and gathered together from across the continents and centuries. My work involves the digitization of these individuals, photographing them and transferring the jumbled, fading information from their tags into our online database. I have held in my hands the Xylocopa fimbriata that those London men collected in Guyana, pollen clinging to its hindlegs, the overhead lights reflecting from its shiny, black carapace. In the 01800s, this specimen — and the thousands of others in our collection — helped biologists unravel the mysteries of pollination. In the 01900s, entomologists recorded their names in our logbook as they visited from faraway colleges of their own, using those same insects to expand our understanding of taxonomy, phylogeny, and the natural world; the Xylocopa fimbriata still bears the mark of this surge in taxonomic interest, with multiple determination labels attached to its rusting pin. Sometimes we even find them scattered about, miscategorized or filed under archaic names. Part of my job is reuniting lost souls with their species, until a new determination splits them apart again.

For now, in the twenty-first century, these individuals are once again at the heart of research. Their digitization is paid for by a climate change grant, and our dorsolateral photography allows measurement of these bees’ intertegular distance, the space across their thorax and between their wings. As the planet warms and their habitats worsen, this distance shrinks, and their flight is impaired; we can see this change in action, thanks to the centuries-span of our collections — the Xylocopa fimbriata from 02010 look markedly different than those from decades past. With their locality tags, we can track the areas most at risk, and thanks to their determinations, we know which species are most in need of our help and protection. In a sense, these individuals are still very much alive, even two hundred years after their collection, because they are contributing to the continuation of their living descendents.

A dorsolateral photograph of a fimbriata specimen that helps scientists measure intertegular distance. Photograph courtesy of the author, specimens courtesy of the University of Michigan Entomology Collections

A dorsolateral photograph of a fimbriata specimen that helps scientists measure intertegular distance. Photograph courtesy of the author, specimens courtesy of the University of Michigan Entomology CollectionsThere is no doubt that advancements in imaging and field research will continue to diminish the need for pilgrimages to central collection centers such as ours, with hundreds of thousands of specimens from every domain of life. Across from me in the lab, my friend creates three-dimensional models of our most attractive specimens, practically replacing the need to look at any physical insect. But a model cannot have its genes mapped, or pollen and parasites removed from its delicate legs for studies on symbiosis. Just as the entomologists of 01845 had no idea their specimens would someday be used to track changes in the global climate, we don’t yet know what will become of our collections. Our role is to treat them with respect as we transfer a small piece of their essence to the digital space, and to ensure their preservation for the generations that follow us.

Our world is changing. Our pollinators are slowly changing, too. Our time on this world is short, both human and bee, passing through places that forget our names as their names are forgotten to us. It is through science that we are granted brief immortality, adding our knowledge to the common pool, writing our names on the labels of the specimens we gather and determine, and preserving ourselves as we preserve them. It is together, collector and collection, that our lifespans stretch for centuries.

August 23, 2023

The Commodification of Air

In the early 01990s, a team of eight scientists and researchers were hermetically sealed into a series of geodesic domes to live for two years. Motivated by a vision of the future in which we might fully simulate nature itself, Biosphere 2 (a humble successor to Biosphere 1, which is what the researchers called planet Earth) would aim to recreate a world in miniature: a complete ecosystem that would allow these econauts to exist in their glass cages in perpetuity. After a few months, however, the habitat became dangerous. Microbes in the soil were churning out CO2 at rates that the young plants couldn’t absorb. Asphyxiation was encroaching. Eventually, a truck had to come in and pump oxygen directly into the structure, breaking the experiment’s hermetic seal and reintegrating it with the broader world — an emergency measure taken after the resident doctor began to struggle with the simple task of adding a column of numbers together.

Though this surreal excursion into the limits of environmental simulation might initially appear far-fetched, it is in many ways a synecdoche for our contemporary relationship to the built and natural world. We’ve long been attempting to craft our own personalized biospheres. From our air-conditioned, seat-warming cars to our massive office buildings with secured windows and central air, we’ve created a comprehensive range of self-contained habitats designed to be immune to outside conditions, capable of being regulated and manipulated at will. The sociologist Jean Baudrillard sensed this fact when, writing on the project, he claimed that “when you leave this virtual biosphere to go back into the real, you notice that the whole of American society is already living in the same conditions… of the biosphere module.” This simulacral logic would be readily adopted by neoliberal capitalism as companies looking for new avenues of profit would begin to productize these simulated environments — transforming the very air we breathed into a manufactured, commodified good.

The glass domes of Biosphere 2 created an illusion of environmental self-sufficiency belied by its own equipment failures. Photo courtesy of Christopher Michel

The glass domes of Biosphere 2 created an illusion of environmental self-sufficiency belied by its own equipment failures. Photo courtesy of Christopher MichelThis gradual transformation of air into a commodity has accelerated in recent years as ongoing pandemics and climatic catastrophes have continued to shape our relationship to wellness and health. As science writer Eleanor Cummins observes, we’ve seen people increasingly turning to “air purifiers and skincare products to address air pollution,” adhering to the gospel of consumerism to reckon with ecological disaster. These days, the air purifier industry alone is estimated to be worth nearly $14 billion and is set to grow; as one 02022 report states, “more than 40% of Americans (over 137 million people) live in areas with failing grades for harmful levels of particle pollution or ozone. This equates to 2.1 million more individuals breathing polluted air than the previous year.” In short, the market opportunity is expanding.

At the core of this phenomenon — beyond all the avarice and opportunism that might surround it — lies the biospheric belief that if we put up enough walls between ourselves, we’ll be able to realize a totally safe, self-insulated ecosystem. Yet the failures of the Biosphere 2 project reveal that enclosure and privatization will lead to suffocation. There is no salvation to be found in this “gated community for one,” as the political art group The Yes Men put it; there will be no oxygen truck to save us when things go awry. Instead, we need to resist this transformation before it's too late — to enshrine air as an elemental right that cannot be bought or sold. Doing so is the only way that we might avoid breathless ruin.

Although this commodification of air may have been brought to popular attention by recent global events like the COVID-19 pandemic, its cultural roots invoke a history that reaches back millennia. The desire to escape bad air goes as far back as the ancient Greeks, when miasma theory would link our notions of air and health — a connection that runs so deep that even our word for malaria stems from the Italian “mala” (bad) and “aria” (air). Likewise, the aristocracy have an extensive tradition of going to the countryside as a way to escape city fumes and bask in the fresh air. During the 01900s however, air — like the “commons” before it — would retreat into the walled enclosures of private property, replaying the propertarian maneuvers of the preceding centuries in this new domain. Two intersecting developments in particular would help establish the foundations for our modern privatized relationship to air: the technological realization of artificial environments, and the gradual transformation of natural air into contaminated air.

Historically, artificial climates were the purview of science fiction, a thought experiment exploring what it would mean for us to transcend our primitive, natural state and have complete authority over the environment. Modern instances include the hedonistic spaceships of WALL-E or the microcosmic train in Snowpiercer, but its origins in the genre go much far back. In the early machine age, for example, the underworld became a popular trope in futurist imagery — a space “where the organic is displaced by the inorganic, where the environment is deliberately manufactured by human beings rather than spontaneously created by nonhuman processes,” as Rosalind Williams writes. In the 20th century, technological developments would enable this fantasy to slowly creep into reality. Apparatuses like air conditioning would first actualize the idea of a “totally artificial indoor environment, independent of the natural climate,” as Gail Cooper writes in Air-conditioning America. Buildings — once largely seen as semi-permeable membranes in which air from the outside would freely pass through to the inside — became insulated boxes, technologized sites of control. The open windows letting in the breeze would be sealed shut in favor of cool, man-made air. These developments would culminate in experiments like Biosphere 2, which attempted to sublimate every aspect of the environment into a synthetic superstructure. Air could now be something created by these tools on-demand, a product delivered on tap.

In Claude Monet's paintings of Saint-Lazare Station in Paris, the dark smoke of coal-powered trains overtakes the sky and the built environment.

In Claude Monet's paintings of Saint-Lazare Station in Paris, the dark smoke of coal-powered trains overtakes the sky and the built environment.At the same time, our relationship with shared natural air was changing in the wake of mass industrialization. Consider Monet’s famous Gare Saint-Lazare series, painted in the late 19th century. Notice the billowing train smoke that overtakes the sky behind it. In these paintings, cloudscapes, once a marker of the natural sublime, have become a marker of the technological — reflecting the growing awareness that even the skies were now impacted by our works. While this sort of man-made smoke was initially considered relatively clean (since miasma had historically been associated with decaying biological matter), artificial fumes became an increasing point of concern for the general populace throughout the 19th and 20th centuries as they began to be associated with an array of health issues.

The air and skies continued to take on an increasingly dark, deadly character in the decades to come. World War I introduced mustard gas into the arsenal of war, turning the environment itself into a weapon. As Peter Sloterdijk writes in Terror From The Air, with “gas warfare, the fact of the living organism's immersion in a breathable milieu arrives at the level of formal representation” — it becomes a fact that is both manipulable and strategically leverageable. World War II and the development of the atomic bomb spread irradiated particles into the atmosphere, which would linger for years to come. Meanwhile, the Holocaust would forever reveal the genocidal possibilities of gas, transforming it into an agent of death on an industrial scale. Today, we’re continuing this legacy of loss. Year after year, wildfires deposit smoke across the globe, new particles like aerosolized microplastics are found in the air, and noxious black clouds emerge from chemical disaster sites.

The advent of airborne chemical weapons in the First World War set the tone for a century of noxious, amorphous threats from the air.

The advent of airborne chemical weapons in the First World War set the tone for a century of noxious, amorphous threats from the air. These two intertwined histories of technological development and environmental loss would propel each other forward. As our notions of “natural,” clean, public air slowly unraveled, we’d begin to fetishize the emergent possibilities of artificial, private air. Tellingly, the techniques that we associate with our modern synthetic ecosystems often originate as a direct response to our pollutive history. As Sloterdijk notes, the gas masks introduced in WWI were the “first step towards the principle of air conditioning, whose basic idea consists in disconnecting a defined volume of space from the surrounding air,” in creating a private ecosystem separate from the public one. Later on, HEPA filters — which have become the gold standard for commercial air filters — were developed to be used alongside the Manhattan Project in an attempt to filter out irradiated particles. Only the air that we made ourselves could be trusted in this increasingly toxic landscape. In the summer of 02023, smoke from devastating forest fires in Canada swept into New York, transforming the sky into a raging red haze. Amidst an air quality alert, the government encouraged us to build our own “clean rooms” — spaces sealed from the outside and filled with ACs and air purifiers. The biospheric message was clear: public air is lost; it’s every man for himself.

Clean air has become scarce — and where there is scarcity, there is demand. The technological advancements over the past century would allow companies to turn air (that once immaterial, ungraspable thing) into a man-made product that could be sold to meet this demand. The insulating logic of the biosphere — the air-conditioned techno-culture that arose in conjunction with ecological corruption — was tailor-made for neoliberal capitalism. The view that the environment is something that can be personalized resulted in the belief that a healthy and sustainable milieu was merely a matter of personal choice, something for the individual to solve through consumption. Air was no longer a public matter that institutions were responsible for, but rather just another good subject to market forces, a question to be settled between private industry and individual consumers. If we lacked clean air, then it’s because we simply didn’t want it enough, or work hard enough to afford it. By framing air quality as a private concern, conservative governments were free to continue their campaign of deregulation and create a new market that companies could rush in to fill.

All across the globe, we’re witnessing the long-tailed impact of this approach. Akanksha Singh reporting for Wired notes the growing “pay-to-breathe” economy among the upper and middle classes in India — where air-filtered homes, malls, and cars are beginning to transform clean air into something experienced only by the wealthy. In the US, there was a spike in air filter sales that occurred at the start of the pandemic, and continuing ecological crises are feeding this consumerist impulse. Even ridiculous products like the Dyson Zone — an air filtering headphone that was initially panned by critics — are gaining new hype in the wake of wildfire season. Meanwhile, companies like Vitality Air are literally bottling up fresh air to sell as a luxury good under the guise of environmental justice (“everyone should be entitled to fresh clean air,” they write magnanimously before selling bottles for upwards of $10,000).

Critically, the commodification of air doesn’t just stop at the sale of filtering technologies or bottles of air. We can see it at work in policy as well. Take the idea of “carbon offsets,” which allow companies to buy certificates associated with climate change harm reduction rather than actually reduce their own CO2 production. In effect, this transforms air into a fungible, unitized good that can be traded in the global market. It imagines air as something that can be packaged, quantified, and redistributed — treating the “good air” produced by offset providers as a discrete object that can be sold to corporations in order to negate the effects of the “bad air” that they are emitting. By purchasing these eco-indulgences, companies can spend their way to absolution instead of actually transforming themselves. Given the logic of the market, however, there’s little incentive for either company or creditor to be particularly meticulous when it comes to actual harm reduction. After all, since the air itself can’t be exchanged, the moment of value creation occurs when money is exchanged for credit (when corporations can say they’ve done their due diligence and when providers get compensated), rendering the real planting of trees or the prevention of deforestation a secondary concern. This helps explain why up to 90% of offsets from the leading carbon standard Verra were recently discovered to be worthless. An attempt to subject air to trade in this manner only results in its further loss.

Companies like Vitality Air have made air into a consumer good, selling the promise of "clean air" for thousands of dollars.

Companies like Vitality Air have made air into a consumer good, selling the promise of "clean air" for thousands of dollars.This individualist, consumerist attitude will only exacerbate the inequalities currently plaguing us. Air is already far “from equal across the planet,” as the cultural geographer Peter Adey puts it, and existing socio-economic infrastructures have long prevented its equal distribution. In the US, decades of residential segregation have made it so that Black Americans are disproportionately exposed to pollution. Commodifying air will disenfranchise those who need it the most, which is all the more concerning because bad air has the capacity to reinforce racialized notions of “cleanliness” and “purity.” In the not-so-distant past, polluted air was closely linked to fears of “racial degeneration” according to the historian Peter Thorsheim; American slavers once attempted to propagate the narrative that Black bodies were naturally immune to yellow fever in order to justify subjecting them (and not white laborers) to lethal conditions. There’s a real risk that we will blame the victims of environmental injustice for the hazardous conditions they find themselves in, intensifying the vicious cycle that runs between misplaced responsibility and social neglect.

At a global level, this commodification also has a tendency to feed into a subtle form of neo-colonialism insofar as it involves countries in the Global North “offsetting” their activities by dictating land and resource management in the Global South, distributing responsibility in ways that hinder the latter’s economic potential. As Ariel Cohen bluntly writes in Forbes, “expecting the global south to play an equal role in decarbonization when they have unequal means is to curse it.” Looking forward, it’s strikingly clear that we cannot rely on more “markets” and private biospheres to address the challenges facing us — they are too short-sighted, too narrow, too self-interested to equip us with the tools we’ll need to pioneer a more equitable future.

Shortly after wildfire smoke descended on New York in early June, searches for “sell my house fast” spiked. In many ways, it emblematized the misguided, unimaginative state of our culture today — a refusal to acknowledge our interconnectedness, a desire to retreat into our isolated silos. The frightening truth, however, is that there’s nowhere to run. No matter how fast you sell your house or how many filters you set up in your apartment, the “slow violence” of ecological collapse is destined to catch up. If we’re to avoid catastrophe, we must relearn how to “breathe together,” as STS scholar Timothy Choy writes. There is no singular solution to this global issue. Rather, we’ll need to pursue interventions at every level of organization.

Interpersonal webs of empathy and support will be critical to developing any resilient ecology capable of absorbing the shocks to come. Victoria Nguyen, for example, writes on the grassroots “respiratory publics” being formed in Beijing — where practices like the online image-sharing of smog levels, care-based circulation of face masks, and utilization of publicly accessible “respiratory refuges” like community centers are creating a bottom-up response to local atmospheric conditions. Through these “publics” (which can range from the practices that Nguyen observes, to forums that disseminate instructions on DIY filters, to “buy nothing” groups that share resources like purifiers in times of need) air can become a shared “object of concern and daily intervention” for the community at hand. The COVID-19 pandemic only served to reinforce the importance of community-level initiatives and personal practice when dealing with such aerosolized threats.

Zou Yi's images of 9 months of Beijing air quality. Courtesy of Zou Yi.

Zou Yi's images of 9 months of Beijing air quality. Courtesy of Zou Yi.Large-scale, top-down initiatives will also be necessary if we are to reclaim public air. This includes not only the tighter regulation of industry and the implementation of environmental protection laws, but also new technological and legal architectures that will help us realize air as a shared medium of life. NASA, for instance, is working to create a more detailed portrait of air quality in the US through the deployment of satellites that can supplement ground-level observation systems. A highly sophisticated level of monitoring will be the first step in making the air epistemically tangible in an active, actionable sense — allowing us to identify the areas most in need of additional resources and initiatives in real time. Policies can also help enshrine clean air as a human right (a broad claim that the UN recently made, but which we should hope to eventually see reflected in practice). There are laws in New York City that require building owners to provide heat and hot water to their tenants — what would it mean to extend this to clean air? Thinking of air as infrastructure can help us reimagine our relationship to it at a systemic scale, attuning us to the channels and mechanisms we’ll need to build out for its proper distribution. It can also reveal how air is bound up with other infrastructures (such as transportation infrastructures, a fact that mobility changes during the pandemic made clear) to help us consider more holistic approaches.

Perhaps most fundamentally, we must learn to re-enchant ourselves with air — that substance that binds us together, that fuels the fires of life. We must once again see that this is something too important, too sacred to be treated as a commodity. After all, we refuse to sell organs because we think that the act of assigning a monetary value to this object violates human dignity. A similar prohibitionist lens could be applied to the air we breathe. Companies once again might have to reduce their CO2 output by improving their own processes, instead of trying to buy good will (and clean air) on a global market; people might once again realize that no amount of insulation will ensure the safety of one without also guaranteeing the safety of all. In the long term, we’ll need a broader cultural transformation to right our relationship to air — to recognize it as a shared reality and realize that our attempts to privatize and commoditize it are doomed to failure.

Our treatment of air over the past few centuries has caused us to forget its ubiquity. To forget that we cannot separate ourselves from it, that we are necessarily immersed in it, that it will seep through the smallest cracks and traverse the largest continents to find its way to us. We must come to accept this fact and face it head on — not with rigid biospheres and insulated borders, but with porous solidarity — if we are to build a more sustainable future. Ultimately we will need to work together as individuals, communities, and governments to reassemble our notion of a shared, public atmosphere. Only then might we be able to secure a world in which we’re able to truly breathe freely.

August 16, 2023

[A Composition of Matter]

![[A Composition of Matter]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1692283100i/34617692._SY540_.jpg)

I:

In youth, I read of sex, and now it’s death —

not out of gloom but for a need to know

the best response to what sidles up in stealth,

and to train myself in the art of letting go.

Best is if the writer sounds like me, wry

and frank about the loss, not Hallmark card,

but impious. But part of me knows that, try

as I might, there is no practicing. The hard

truth is that diminishment may not creep at all,

but roar down as a tornado does, ripping

off the roof and revealing the whole as fragile.

Perhaps nothing at all is gained by this reading

apart from a solidarity in trepidation,

making sense of life a shared vocation.

II:

Making sense of life’s a shared vocation

that even the trees teach me as they fall, the rot

not always obvious. Cautious, I station

myself back from heavy limbs at lights,

having awakened to my hundred year old willow

snapped quietly in half at night. Others,

succumb to drought or ice. An arborist told

me they also have a set span of years,

which I remind myself after abstaining once

too often. Even the disciplined die, and the Falstaffian

may outlive us yet. Lodgepole cones,

serotinous, need a raging fire to open.

Best just to revel in the day, and by revel

I mean catch the sun and call it ample.

III:

It’s hard to catch the sun and call it ample

though ferns have done so for eons, unfurling

and entrusting spores to wind, to mere dimples

in the soil. Such modesty, with the days hurtling

by. Silt-pressed, some’ve been preserved alongside

their bolder cousins—a triceratops or tyrannosaur,

caught mid-roar. Why this need to stride

above an astonished crowd, wired skull larger

than a car? Birdlike, I sing: I want to matter,

matter, matter. What of all the living things

that never fossilized, that rotted in the same river?

We’re surrounded by the valor of unseen beings.

That we came to be at all is astonishing, a triumph

of coincidences so absurd as to make us laugh.

IV:

Consider the coincidence and laugh, biology outwitting

history—a Jewish daughter born to parents

who escaped the century’s brutal rendering —

an accidental breeching of an egg’s defense.

My angry grandfather told me I was almost aborted —

so there’s that as well, the erasure of an inconvenience.

Nor did I drown in the bath, or toddle into the street,

or remain a spinster, or infertile, giving birth not once

but thrice! You’d think such audacity would hold

pride of place on the mantel, like a trophy, remarked

on by guests. Once we spent an afternoon embroiled

in finding my daughter “a treasure button” in the park —

Presented it, she whined: Not red! White!

transforming herself in an instant from darling to brat.

V:

The transformation from darling to brat is an old story.

At first, we liberated the lesser gods from laboring

in mud, but then we proliferated and became noisy.

What else but inundation could stop our clamoring?

It didn’t work. With each decade, we bellow

more loudly in the chute, as if hoping

by mere volume to avert the killing blow,

our masterworks a kind of glorified moping —

If we can’t live forever, maybe something

of us can, if only synapses, uploaded,

Utnapishtim’s immortality in the pulsing

bytes, our flesh and blood outmoded.

How could this help when even a long Sunday

leaves me desperate for the relief of Monday?

VI:

The empty hours an ache, I long for Monday.

I’d cling to even the dullards in my schoolroom

like one rescued from a raft after months at sea.

The vastness is too vast, and me a crumb.

Clearly, then, leisure is not the eternity

I seek—rather for some essential me-ness

to linger, for future people to praise my

having been the way I do when I listen

to Bach fugues or read of Melville’s Ahab.

Some make wealth their shield against the void,

vaulting themselves within it like calcareous crabs.

It helps the living but does nothing for a dead

poet longing to outlive my final breath

through what I wrote — first of sex, then death.

August 1, 2023

Getting in Touch with "Your Future Self"

We often think about long-term thinking as something that goes beyond the individual — projects that span generations, or intellectual movements and cultures that have lasted through centuries and millennia. But long-term thinking can also be something that you practice in your daily life — the choices we make about everything from our careers to the communities we make our own. Yet making those decisions is sometimes easier said than done.

To explore the reality of long-term thinking in the world of personal decision making, we spoke with Hal Hershfield, Professor of Marketing, Behavioral Decision Making, and Psychology at UCLA’s Anderson School of Management and author of Your Future Self: How to Make Tomorrow Better Today, a new book that explores how we can balance living for today and planning for tomorrow by making deeper connections with our future selves. In our wide-ranging conversation, Hal discussed everything from the psychology of chance encounters to what he sees as the greatest success of long-term thinking in contemporary society.

The following conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Long Now: I was very much struck by a passage in the book where you talk about how we as humans overweight the present by seeing it as if “it's a expansive time that's divorced from the rest of our timelines, which it is simply not.” Here at The Long Now Foundation, we often talk about the long now as a tool for thinking about time where we expand what we think of as the present into the traditional domains of the past and the future. Do you see that as a useful way out of the patterns that you're identifying?

Hal Hershfield: So I do agree — to some extent. When I talk about us overweighting the present so much that we divorce it from the rest of time, what I mean is that sometimes, we fail to see how the individual presents add up to a cumulative future. I think you [at Long Now] are taking our traditional sense of the present and making it more expansive, making it more of an umbrella that includes the recent and even more distant past plus the more proximal and more distant future. The advantage there is that I think it can help convey the idea that various futures are part of who we are right now.

The one caveat is that we sometimes do more harm to ourselves than to others. Think about smoking. If I say “don't smoke, it's bad for your health,” you can respond, “I know, but I'm still gonna do it.” If I instead say, “Don't smoke. It's bad for your kids or your loved ones,” you might instead think, “Well, I don't want to ruin someone else's health.” So there are times when it makes sense to make some separations between generations, because my negative behaviors could be affecting other groups and other generations. So if they're separated out in that regard, then it can be motivational to get us to change whatever we're doing that could harm them. But if we include all generations and all groups into one big present, I may have an easier time justifying harm.

Similarly, there have been many attempts to form various citizen assemblies that try and make a voice for future generations who can't literally be there. But it always feels tricky — because you try to represent the perspective of people who are as of yet not born or are very young now, but you can't actually represent those perspectives accurately. There's an epistemic humility argument to this where you have to acknowledge that you can't really know what these future people want. Some talk about this dilemma in terms of preserving options for future generations.

I love that because the same applies for our own future selves. I truly can't know what I'm gonna be like when I'm 65. I can take some guesses — in the same way that I can take some guesses as to what humanity will be like in 2, 3, 7 generations. I really love the idea of preserving options. In a way it's very western, the idea of prioritizing freedom of choice applied intergenerationally.

Yeah. It's kind of funny writing a book for people to help them to understand their lives and the problems that they’re grappling with — a book about ways of time management and planning for the future — where reading a book is for many people a time commitment in itself. Are there one or two key insights in particular from your book that you would want someone who is currently feeling disconnected from the future self to grasp?

Buy the book! It makes a great coffee table piece. I’m kidding, of course. The one big takeaway is that our future selves can be thought of as other people. What matters is the type of relationship that we foster with them and that, when we make choices now, they will impact this other person, this other version of ourselves. So I would say the thrust of the book is figuring out how to create some harmony between the needs and wants of our current selves and the needs and wants of our future selves. But it's not all about sacrificing today for tomorrow. Instead, it’s about figuring out the harmony so that I can live my life now and enjoy the present, but do so in an intentional way so that my future self also has freedom of choice and can live the life that they want to live as well.

Something that was very impactful on that note in the book was in the last few sections, where you talk about, for example, people who use a decent portion of their savings to go on a particular vacation. You note that to do so is not a failure of this model of thinking of your future self but that it's actually, supporting the model – in a different way than what you might first expect, which is a really helpful introduction.

Hal Hershfield

Hal Hershfield

Much of your book focuses on matters that are to a large degree within our control in our individual lives. For example: what choices, decisions, or plans can we make in our day-to-day? So, how does the model of thinking about our future selves account for and grapple with developments that are chance-based or out of our control, as many things are?

I think it's a fascinating question that you're asking. Albert Bandura — a cognitive psychologist — wrote a paper from about 40 years ago called “Chance Encounters and Fortuitous Life Paths.” One of the things that he talks about is the idea that we can't fully anticipate how different chance encounters can impact the paths that we take. We only have so much control over our lives, right? Yet we can strive for agency so that we are making decisions to put ourselves into situations where we may come across positive chance encounters that can positively impact the directions that we go in.

To make that a little more succinct: we can only plan so much. We don't know the different directions our lives will take because we don't know the different fortuitous encounters that will occur, but what we can do is be prepared for them and treat our future selves with a degree of fluidity and flexibility. Take the Western notion of “I'm going to get married by a certain point and have kids and this and that.” That strikes me as like a life that's destined to be met with some disappointment because of how hard it is to meet those marks. But if we're open and have a focus on values that we want to have present in our lives from now to later, then I think it will create more receptivity to chance encounters.

On that point: I think many people perceive those stages of life and relationships as a kind of escalator. You get on and you move through phases of life very programmatically. That doesn't actually end up being true for most people, which is where a lot of stress comes out. The point you've made in the book about over-planning and feeling overdetermined in life feels very real to many.

Escalator feels like the right metaphor. It's funny — with my kids, we're in the midst of reading Charlie and the Great Glass Elevator, the Roald Dahl book. There, the elevator goes all different directions and that feels more like a realistic model of life.

Near the end of the book, you discussed planning for death. You discuss what you call a “mature view of time” where people recognize and “can plan for a given future, but also feel differently about those plans as time progresses.” In a certain sense, this view is oppositional or questioning the traditional ideas of long-term planning, of setting the foundations for something that will keep going in the future with clear plans. You make clear that it's not truly one or the other and that both perspectives are valuable. How do you feel we can best incorporate these different approaches?

I, of course, don't view it as being antithetical to traditional long-term planning. However, I could see how that could be perceived that way. There's a benefit to locking in plans and especially making long-term contracts. To some extent, this is how we preserve institutions. So, if we said, “Well, this is a heritage site, but we'll revisit it in three years,” it really wouldn't be a heritage site, right? There's something a little bit different there because we're talking now more intergenerationally versus on an individual level.

The thrust of that perspective was that we may find ourselves in a detrimental position if we adhere too rigidly to plans, or adhere too rigidly to our expectations that things will work out a certain way and so we may do better to pay attention to what I call the Big Why: What is the thing that's driving you? From there, maintain some flexibility around the ways that you execute those plans over time. Applying that to the intergenerational context — I think this is a little bit trickier. I agree that to some extent, intergenerationally, we want to apply more rigidity. One way to do this is to open up the flexibility around some peripheral aspects of the way a plan is carried out. If we allow flexibility at the core of a plan through an intergenerational perspective, then that may be problematic because now we all of a sudden may find ourselves shifting gears solely as a function of fads or whatever current zeitgeist might be. So that does represent a contrast between intra-individual planning and inter-individual planning.

It's tricky! In all these cases there is definitely room for both rigidity and fluidity, changing over time. One project that does do this intergenerationally over a very long time scale is the Jewish oral law. There’s a core that's the scriptures [of the Torah] . Then there's generation after generation of people — different rabbis and scholars — debating over it while still working from the same core.

That's a really good example. Thank you for raising that.

Near the end of the book, you quote Alexander Rose, our now former executive director , who says “many of our present problems are because of a lack of long-term thinking in the past.” You talk about a number of those problems. From climate to our built environment people are aware of the ways in which short-term thinking in the past has failed us. So I want to flip the question around and ask: While you were writing and researching this book, did you come across particular cases of the benefits that we have reaped from prior generations thinking of their future selves? Are there success stories in this variety of long-term thinking that we can see in our society today?

That's a really great question; it's positive and optimistic. Probably the first thing that comes to mind is the concept of a retirement system and social security system. It’s still a great example of thinking ahead. When that was created, of course, average life expectancy was considerably lower than it is now. So there was less of a burden on the part of the state to support people after they retired, but even so it represented really forward thinking because, by putting that system into place, it did create a safety net for people after they retire. To me, that’s an example of a future thinking starting a long time back that is quite positive.

That also feels like a great case study in that it's people thinking of their individual retirements when they pay into it, but actually each of those are going to pay for other people's retirements collectively on a generational scale. It's subtly working in this idea of supporting your own future selves and collective futures as well, which is very exciting.

It's true. I wonder how many people think about the collective aspect of it — because once you get into the weeds of social security you quickly realize that you’re paying in right now for other people — I don't know how well that's framed and understood on a general level. But, you're absolutely right. It's a great example of that.

And we've made it so normal and such a core, untouchable part of our social fabric, which is not something you could have predicted a generation prior to when the program was implemented.

That's so true. That's probably my best example.

Thanks so much for talking with us.

Your Future Self

is out now from Little Brown Spark.

July 26, 2023

The Future Of Invasive Species Mitigation

In the heart of the Jiangxi Province of China lies Poyang Lake, the largest body of freshwater in the nation. The lake, which is part of the Yangtze River watershed, is an oasis of biodiversity. A visitor to the shores of the lake could on any given day in the wet season see a “river pig” — an endangered finless porpoise — or one of the dozens of migratory bird species that winter on the lake, most prominently the Siberian white crane.

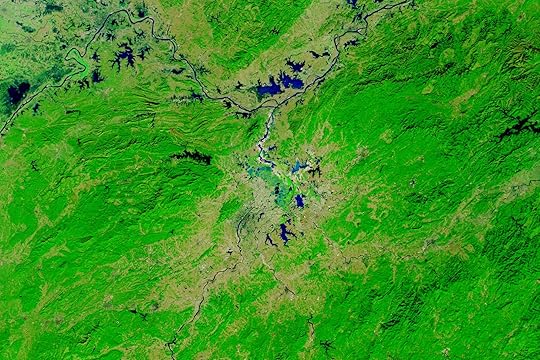

Poyang Lake in the wet and dry seasons. Data from NASA Earth Observatory

Poyang Lake in the wet and dry seasons. Data from NASA Earth ObservatoryThe abundance of species has proven effective at energizing the local economy, which relies heavily on the aquaculture of non-native species such as sturgeon, tilapia, red swamp crayfish and white freshwater prawn which were introduced by a burgeoning aquaculture industry around 02000. This influx of non-native species, however, has also shaken up the lake’s ecological balance. Parrot’s feather, a species of rooted emergent flora native to South America that was introduced to the lake in order to support habitats for red swamp crayfish, has started to outcompete native plants for space.

A study published in BioInvasions Records, an academic journal dedicated to the study of invasive species, found that this plant is not only displacing native competitors, but also facilitating the invasion of western mosquitofish by providing wider refuge from predators. The effect of this invasion dominoes as the influx in mosquitofish prey on native amphibians, reptiles and fish at unsustainable rates.

Parrot’s feather is just one of the non-native species beginning to affect the greater balance of Poyang Lake’s ecosystem. In a recent lake-wide survey of species published in Aquatic Invasions, an average of 4.36 new species are discovered within the lake’s basin every year, providing more pathways for non-native competitors to wipe out species that have called it home for centuries and even millennia.

Parrot’s feather (Myriophyllum aquaticum). Harry Rose from South West Rocks, Australia, CC BY 2.0 , via Wikimedia Commons

Parrot’s feather (Myriophyllum aquaticum). Harry Rose from South West Rocks, Australia, CC BY 2.0 , via Wikimedia CommonsPoyang Lake is not the first ecosystem to be threatened by influxes of new species, but it could be a bellwether for how unmitigated invasive species can affect even the most biodiverse ecosystems. In an increasingly globalized world, these dynamics of invasion are becoming exponentially difficult to delay, let alone stop.

Scientists have already observed the ecological collapse that can result from unmitigated invasive species. A study conducted at the University of Cambridge in 02021 tracked the effects of invasive Asian silver carp and American signal crayfish on bodies of freshwater. The resulting over-consumption of lakes’ native species resulted in increased water turbidity, creating perfect storms for toxic algal blooms in each scenario. Once the turbidity of the water exceeded critical levels, the algae poisoned the water supply in each lake, killing native fauna and blocking sunlight required for native flora to grow and replacing the once biodiverse aquatic habitats with algal wastelands.

Governments and international organizations are already making slowing the spread of invasive species a priority. The UN Convention on Biological Diversity, signed into action in 01993, establishes the obligation of its signatories to “prevent the introduction of, control or eradicate those alien species which threaten ecosystems, habitats or species.” In the decades that have followed, conservationists have taken this obligation to heart, exterminating non-native species using pesticides, hunts, and even gastronomy.

Detection & PreventionYet these efforts may in some regards be overzealous. Not all species that newly enter an ecosystem are invasive species, and the distinctions between varieties of non-native species are key to managing them.

“Invasive species are, to the scientists who study them anyway, a subset of non-native species. In popular literature, the two terms are used synonymously,” notes biologist Dr. Daniel Simberloff, Gore Hunger Professor of Environmental Science at The University of Tennessee. “To people in the field, a non-native species is a species that isn’t native to an area and arrived there with human assistance, either deliberately or inadvertently.”

This distinction is paramount, as not all non-native species become invasive. Many species establish small populations that either remain secluded and non-threatening or go extinct in that environment altogether, many of which scientists don’t ever know about.

“We wouldn’t call those invasive,” says Simberloff. “A lot of ornamental plants that are also deliberately kept in people's backyards are non-native […] but they can't survive without human assistance, so we wouldn't call those invasive, either.”

Although it is possible for non-native species to establish populations outside their domain of origin and remain benign, it’s challenging and sometimes impossible for scientists to accurately determine if or when a species will become a threat to an established ecosystem until after the invasion has begun.

“We don't really know how many non-native species arrive and don't even establish populations, or their populations are established, but then go extinct very quickly,” says Simberloff. “There are a few cases where we do have some real data, and those are for deliberate introductions where there are good historical records.”

Simberloff cites cases where species were introduced intentionally for biological control purposes. In these cases, a predator or competitor is temporarily introduced or even established permanently to reduce or remove populations of undesired species in a given region. In other cases, invasive species are introduced via shifts in climate, societal changes or individual actions.

Benign non-native species can also become invasive over time. There’s always a possibility that an introduced population could skyrocket at a moment’s notice, given proper conditions, which can shift through human interference or even natural means.

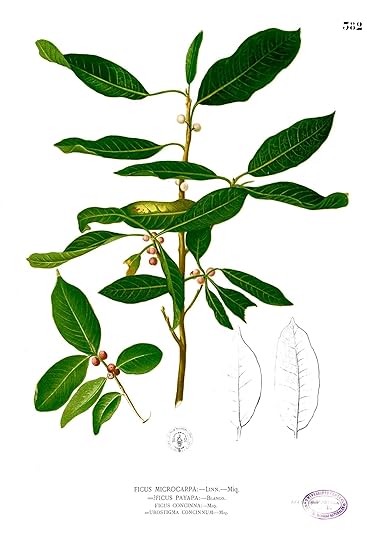

Ficus microcarpa, the laurel fig, and Eupristina verticillata, the wasp that pollinates it and allows for it to spread as an invasive species.

Ficus microcarpa, the laurel fig, and Eupristina verticillata, the wasp that pollinates it and allows for it to spread as an invasive species.Ficus microcarpa, native to India and Malaysia and commonly known as laurel fig, is a prime example of a late bloomer in invasion ecology. The fig was commonly kept as an ornamental plant in Coral Gables and Miami, Florida for decades before its wild population inexplicably spiked, strangling native host trees and shading out potential competitors. As it turns out, a key component of its reproduction involved a companion species of wasp.

“Every fig has to be pollinated by its own species of fig wasp. If that fig wasp isn't there, that will be a sterile plant; it’s not going to reproduce,” Simberloff explains. “Suddenly — we don't know how — its fig wasp arrived, and then the fig started to spread.”

This “lag phenomenon” described by Simberloff is often one of the variables that makes it so difficult to predict if a certain species will become invasive. If there is even an inkling of a possibility that the necessary conditions could be met, therein lies the potential for a non-native species to become a problem.

Some nations with particularly delicate ecosystems have employed strict legislation and policy to prevent non-native species from entering, let alone establishing viable populations. The island nation of New Zealand has stringent regulations on the importation of animals. According to their Environmental Protection Authority, “some organisms are considered very high risk to the New Zealand environment and must never be imported, developed, field tested or released.” The country’s expansive list of barred species includes snakes of any kind and several other examples of fauna, including snails and mammals.

Furthermore, biosecurity appears to be a communal value in New Zealand, so much so that there is both a dedicated pests-and-disease hotline and government smartphone application available to assist in the identification and reporting of unwelcome species.

1: Lymantria dispar, the spongy moth, can be a vicious force against forests. (By Didier Descouens - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0) 2: A forest in Pennsylvania infested by the moth. (Dhalusa, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons) 3: Even in New Zealand, a country known for strict invasive species restrictions, efforts to prevent the spread of species like the spongy moth can prove controversial.

1: Lymantria dispar, the spongy moth, can be a vicious force against forests. (By Didier Descouens - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0) 2: A forest in Pennsylvania infested by the moth. (Dhalusa, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons) 3: Even in New Zealand, a country known for strict invasive species restrictions, efforts to prevent the spread of species like the spongy moth can prove controversial.Although New Zealand has established effective protocols, there are still species that slip through the system. In 02003, a population of spongy moth caterpillars emerged. According to the Ministry of Primary Industries, which oversees farming, fishing, and biosecurity in New Zealand, “this moth lays hundreds of eggs in a single mass. The egg masses then hatch, releasing hundreds of hungry caterpillars. These caterpillars can strip the leaves from entire trees, devastating stands of trees.” The moth was later declared eradicated from the country in 02005 after an aerial insecticide campaign led by the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry. Despite New Zealand’s history of biosecurity success, this effective amount of surveillance, policy and mitigation is not as easily achievable in non-isolated nations.

In Europe, the American mink, introduced in the 01920s for fur farming, has established an invasive population throughout the continent and according to Simberloff, “is causing many impacts — not least on the endangered European mink, which is a highly imperiled species.” Despite the known risks that accompany the introduction of the foreign mink, which can serve as a vector for new diseases to the region, fur-farming countries like Poland and Denmark, having culled masses of mink in 02020 due to their vulnerability to COVID-19, have refused to list the species as invasive for economic reasons.

Although the species is among one of Europe’s most invasive, it’s unlikely that the American Mink will be unilaterally designated as such. The failure to internationally cooperate is a phenomenon with which scientists have become all too familiar. For instance, international global warming legislation based on scientific evidence is also frequently stalled due to the varied economic priorities of sovereign governments.

“Both invasions and global warming,” Simberloff concludes, “do not make one optimistic about mobilizing popular pressure to do something that should be done.”

Surgical StrikesIf prevention isn’t reasonably feasible in an interdependent and globalized society, the question remains as to what the best method to prevent all-out ecological collapse is. Looking ahead, Simberloff points to molecular genetics as a potential method. Oxitec, a UK-based biotechnology company, is using this method in its battle against the invasive, disease-spreading mosquito species Aedes aegypti.

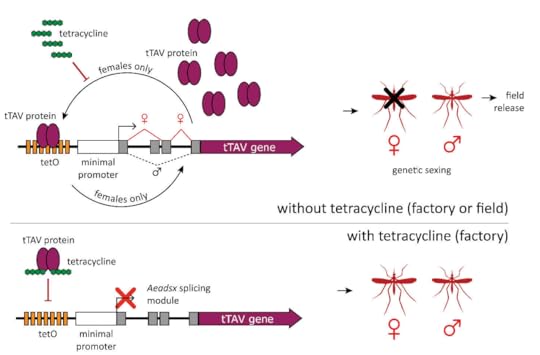

Aedes aegypti is a primary transmitter of Zika, dengue and chikungunya. Initially confined to tropical and subtropical regions, global warming has facilitated the expansion of its viable habitat. Traditional means of pest control like insecticides have proven flawed as surviving mosquito populations gradually evolve resistance to common chemical agents. Oxitec’s genetically modified male mosquito takes a different tack to eliminate non-native populations. The genetically modified mosquitoes released by Oxitec use the universal biological imperative to reproduce against mosquito populations via two inserted genes.

The first gene is for monitoring purposes and produces a fluorescent protein called DsRed2 that scientists can use to distinguish genetically modified mosquitoes from naturally produced mosquitos. tTAV, the protein encoded by the second gene, is the key to restraining invasive mosquito populations. The gene is what’s known as a repressible self-limiting component. When active, it causes the overproduction of tTAV, a protein that interrupts the synthesis of other vital proteins, causing the offspring to die off before they are sexually mature, preventing reproduction. The goal is for released genetically modified mosquitoes to mate with wild females in lieu of wild males, causing offspring to inherit the gene and reducing the population with each generation.

A schematic representation of the OX5034 female-lethal trait mediated through sex-specific tTAV-OX5034 expression. Via EPA decision 549240 for Experimental Use Permit 93167-EUP-E

A schematic representation of the OX5034 female-lethal trait mediated through sex-specific tTAV-OX5034 expression. Via EPA decision 549240 for Experimental Use Permit 93167-EUP-E “It’s just very elegant, very simple, and it just works,” says Grey Frandsen, Oxitec CEO, as he lists the success stories of his company’s gene insertion program. “It’s a really targeted and surgical way to fight any particular pest and do it without any unintentional impact whatsoever.”

Unlike chemical control via pesticides or alternative forms of biocontrol, unintended consequences are largely eliminated according to a U.S. Environmental Protection Agency evaluation. The male mosquitoes do not bite, the control methods only target Aedes aegypti and the genetic modification is non-toxic to predator animals.

Although these scientific advancements provide a glimpse into the future of invasive species elimination, old-fashioned methods to reduce and remove harmful populations should not be discounted.

“The third general approach is mechanical or physical mitigation,” adds Simberloff. “You rip them out or you kill them, what have you. That works sometimes, too.”

The South Florida Water Management District is employing this approach in its lengthy battle with invasive Burmese pythons in the Everglades. The snakes were introduced to the area, likely via the pet trade, and established a breeding population by the early 02000s, shortly before ascending to the top of the ecosystem’s food chain. According to the agency, “Burmese pythons possess an insatiable appetite” and “can not only kill Florida native prey species and pose a threat to humans, but also rob panthers, birds of prey, alligators and bobcats of a primary food source.”

Due to increased sightings and the snake’s threat to native wildlife, the agency started the Python Elimination Program in 02017. The program, which “incentivizes a limited number of public-spirited individuals to humanely euthanize these destructive snakes,” currently pays hunters up to $18 an hour, with additional bonuses for game over four feet in length. Active nest verifications can also earn these enthusiasts a $200 bonus. The program has recorded over 7,000 python removals since its inception.

All methods considered, it’s important to approach invasive species with the nuance that there may be no one-size-fits-all solution.

Although living in a globalized society has contributed to these invasions becoming a near-universal issue, precise research and tactics are needed for each scenario.

This precision and the time it requires is the crux of what makes these crises so difficult to solve. Before research concludes or variables necessary for spread are identified, it’s possible that invasions will have expanded beyond the usefulness of preventative measures.

Furthermore, acting with haste has its own drawbacks as well. Rash measures in the past have had unintended consequences and have also negatively affected local species. For example, The Bald Eagle was on the brink of extinction in North America until it was discovered that the first synthetic pesticide, known as DDT, was hindering the bird’s ability to properly form eggshells.

The reality of the matter is that the happy medium between precision and timeliness in the war against invasive species has been elusive, despite decades of effort on the part of biologists and others working in conservation. Nevertheless, our planet’s precarious ecosystems hang in the balance between these competing tactics.

“All of those approaches have successes and failures,” affirms Simberloff. “It's worrisome and it's challenging. In some cases we have already done a good job. In some cases we could do a much better one.”

July 19, 2023

Shining a Light on the Digital Dark Age

The Dead Sea scrolls, made of parchment and papyrus, are still readable nearly two millennia after their creation — yet the expected shelf life of a DVD is about 100 years. Several of Andy Warhol’s doodles, created and stored on a Commodore Amiga computer in the 01980s, were forever stranded there in an obsolete format. During a data-migration in 02019, millions of songs, videos and photos were lost when MySpace — once the Internet’s leading social network — fell prey to an irreversible data loss.

A false sense of security persists surrounding digitized documents: because an infinite number of identical copies can be made of any original, most of us believe that our electronic files have an indefinite shelf life and unlimited retrieval opportunities. In fact, preserving the world’s online content is an increasing concern, particularly as file formats (and the hardware and software used to run them) become scarce, inaccessible, or antiquated, technologies evolve, and data decays. Without constant maintenance and management, most digital information will be lost in just a few decades. Our modern records are far from permanent.

Obstacles to data preservation are generally divided into three broad categories: hardware longevity (e.g., a hard drive that degrades and eventually fails); format accessibility (a 5 ¼ inch floppy disk formatted with a filesystem that can’t be read by a new laptop); and comprehensibility (a document with an long-abandoned file type that can’t be interpreted by any modern machine). The problem is compounded by encryption (data designed to be inaccessible) and abundance (deciding what among the vast human archive of stored data is actually worth preserving).

The looming threat of the so-called “Digital Dark Age”, accelerated by the extraordinary growth of an invisible commodity — data — suggests we have fallen from a golden age of preservation in which everything of value was saved. In fact, countless records of previous historical eras have all but disappeared. The first Dark Ages, shorthand for the period beginning with the fall of the Roman Empire and stretching into the Middle Ages (00500-01000 CE), weren’t actually characterized by intellectual and cultural emptiness but rather by a dearth of historical documentation produced during that era.

Even institutions built for the express purpose of information preservation have succumbed to the ravages of time, natural disaster or human conquest. The famous library of Alexandria, one of the most important repositories of knowledge in the ancient world, eventually faded into obscurity. Built in the fourth century B.C., the library flourished for some six centuries, an unparalleled center of intellectual pursuit. Alexandria’s archive was said to contain half a million papyrus scrolls — the largest collection of manuscripts in the ancient world — including works by Plato, Aristotle, Homer and Herodotus. By the fifth century A.D., however, the majority of its collections had been stolen or destroyed, and the library fell into disrepair.

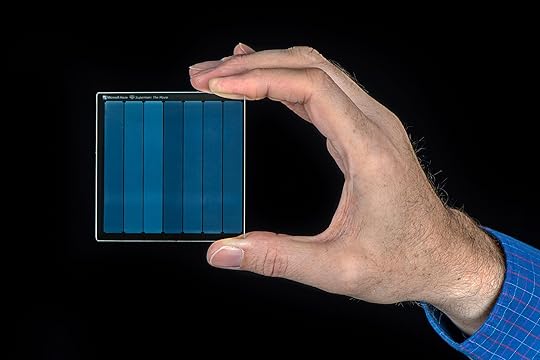

Digital archives are no different. The durability of the web is far from guaranteed. Link rot, in which outdated links lead readers to dead content (or a cheeky dinosaur icon), sets in like a pestilence. Corporate data sets are often abandoned when a company folds, left to sit in proprietary formats that no one without the right combination of hardware, software, and encryption keys can access. Scientific data is a particularly thorny problem: unless it’s saved to a public repository accessible to other researchers, technical information essentially becomes unusable or lost. Beyond switching to analog alternatives, which have their own drawbacks, how might we secure our digital information so that it survives for generations? How can individuals, private corporations and public entities coordinate efforts to ensure that their data is saved in more resilient formats?

Organizations like The Long Now Foundation are among those working to combat the Digital Dark Age (Long Now in fact coined the term at an early digital continuity conference in 01998), drawing on open-source software, coordinated action across platforms, transparency in design, innovative technologies, and a long view of preservation. From thought experiments and industry analysis to more concrete projects, these organizations are imagining preservation on a massive time scale.

The Rosetta Disk is just one possible way that we can preserve linguistic data for future generations.

The Rosetta Disk is just one possible way that we can preserve linguistic data for future generations.Consider the Rosetta Project, Long Now’s first exploration into very long-term archiving. The idea was to build a publicly accessible digital library of human languages that would be readable to an audience 10,000 years hence. “What does it mean to have a 10,000-year library?” asks Andrew Warner, Project Manager of Rosetta. “Having parallel translations was enough to unlock the actual Rosetta Stone, so we decided to construct a ‘decoder ring,’ figuring that if someone understood one of the 1,500 languages on our disk, they could eventually decipher the entire library.” Long Now worked with linguists and engineers to microscopically etch this text onto a solid nickel disk, creating an artifact that could survive millennia. More symbolic than pragmatic, the Rosetta Project underscores the problem of digital obsolescence and explores ways we might address it through creative archival storage methods. “We created the disk not to be apocalyptic, but to encourage people to think about our more immediate future,” says Warner.

💡READ Kevin Kelly's 02008 Long Now essay on the ideas behind the Rosetta Disk.READ Laura Welcher's 02022 paper on Rosetta, archives, and linguistic data.

Indeed, the idea of a 10,000 year timescale captures an anxious public imagination that’s very much grounded in the present. How will technological innovation such as generative artificial intelligence change the way we interpret (and govern) the world? What threats — climate change, pandemics, nuclear war, economic instability, asteroid impacts — will loom large in the next decamillennium? Which information should we preserve for posterity, and how? What are the costs associated with that preservation, be they economic, environmental or moral? “Long Now will be a keeper of knowledge,” says Warner. “But we don’t want to end up erecting a digital edifice in a barren wasteland.”

As personal computing and the ability to create digital documents became ubiquitous toward the end of the 20th century, preservation institutions — museums, libraries, non-profits, archives — and individuals — were faced with a new challenge: not simply how to preserve material, but what to collect and preserve in perpetuity. The astonishingly rapid accumulation of data has led to a problem of abundance: digital information is accumulating at a staggering rate. Scientific, medical and government sectors in particular have amassed billions of emails, messages, reports, cables and images, leaving future historians to sift through and categorize an enormously capacious collection — one projected to exceed hundreds of zettabytes by 02025. The Clinton White House, by one estimate, churned out 6 million emails per year. NASA’s sky surveys rely on over 2 billion uploaded images. The endless proliferation of junk-content, both human and A.I.-generated, makes sifting through all this data even trickier.

The term of art for this sorting is known as appraisal: deciding whether or not something should be preserved and what resources are required to do so. “One ongoing challenge is that there’s so much to preserve, and so much that can help diversify the archival record and reflect the society we live in,” says Jefferson Bailey, Director of Archiving & Data Services at the Internet Archive, a digital library based in San Francisco that provides free public access to countless collections of digitized materials.

Servers housed at the Internet Archive's San Francisco headquarters.

Servers housed at the Internet Archive's San Francisco headquarters.The organization began in 01996 by archiving the Internet itself, a medium that was just beginning to grow in use. Like newspapers, the content published on the web was ephemeral — but unlike newspapers, no one was saving it. Now, the service has more than two million users per day, the vast majority of whom use the site’s Wayback Machine, a search function for over 700 billion pages of internet history. Educators interested in archived websites, journalists tracking citations, litigators seeking out intellectual property evidencing or trademark infringement, even armchair scholars curious about the Internet’s past, all can take a ride on this digital time travel apparatus, whose mission is “to provide Universal Access to All Knowledge.” That includes websites, music, films, moving images and books.

💡WATCH Brewster Kahle's 02011 Long Now Talk, "Universal Access to All Knowledge," on how the Internet Archive, deemed "impossible" when he founded it in 01996, became an essential part of the web.WATCH Jason Scott's 02015 Long Now Talk, "The Web in an Eye Blink," which details Scott's project at the Internet Archive to save all the computer games and make them playable again inside modern web browsers.